Abstract

Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) inhibits leukemia-inhibitory factor (LIF) signaling and acts as a negative regulator. Deletion of SOCS3 causes embryonic lethality because of placental failure, and genetic reduction of LIF or the LIF receptor (LIFR) in SOCS3-deficient mice rescues placental defects and embryonic lethality; this indicates that SOCS3 is an essential inhibitor of LIFR signaling. However, the downstream signaling molecule that acts as a link between the LIFR and SOCS3 has not been identified. In this study we explored the downstream signaling of LIFR. The administration of LIF to SOCS3-heterozygous pregnant mice promotes trophoblast giant cell differentiation and accelerates placental failure in SOCS3-deficient mice. SOCS3-deficient trophoblast stem cells show enhanced and prolonged signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) activation by LIF stimulation. Further, in the trophoblasts of SOCS3-deficient placenta and differentiating cells from the choriocarcinoma-derived cell line Rcho-1 cells, constitutive activation of Stat3 is observed. The forced expression of SOCS3, dominant-negative Stat3, and dominant-negative Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) in Rcho-1 cells significantly suppressed the trophoblast giant cell differentiation of these cells. In addition, the number of trophoblast giant cells is significantly reduced concomitant with an increased number of precursor trophoblasts in JAK1-deficient placentas. Finally, JAK1 deficiency rescues placental defects and embryonic lethality in SOCS3-deficient mice. These results indicate that the LIFR signaling is finely coordinated by JAK1, Stat3, and SOCS3 and regulates trophoblast giant cell differentiation. In addition, these data establish that LIFR-JAK1-Stat3-SOCS3 signaling is an essential pathway for the regulation of trophoblast giant cell differentiation.

PLACENTAL DEVELOPMENT is essential for the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy. The trophoblast cell lineage comprises several specialized subtypes including trophoblast giant cells, syncytiotrophoblast cells, spongiotrophoblast cells, and glycogen cells. More than 100 mutant mouse lines exhibit placental defects due to the absence of factors essential for placental development (1). Trophoblast giant cells are terminally differentiated, polyploid cells that mediate trophoblast invasion of the maternal decidua. The trophoblast giant cell differentiation is tightly regulated by the coordinated activity of a number of maternal and embryonic factors (2).

Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) is a multifunctional cytokine of the IL-6 cytokine family, sharing the common gp130 receptor subunit together with IL-6, IL-11, oncostatin M, ciliary neurotrophic factor, and cardiotrophin-1. In LIF receptor (LIFR) signaling, Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) and Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) are autophosphorylated and activated after ligand binding and heterodimerization of the LIFR-gp130 complex (3). The targeted disruption of the JAK1 gene abrogates gp130-mediated signaling (4), whereas that of the JAK2 gene does not abolish LIF or IL-6 responsiveness (5); this suggests that JAK1 is essential for LIF signaling. Suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins are negative regulators of cytokine signaling; further, SOCS1 and/or SOCS3 can inhibit the signaling cascade of several JAK-STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription)-dependent cytokines, including the cytokines that share gp130 such as LIF (6).

Maternally derived LIF is essential for early implantation (7). Deletion of LIF receptor (LIFR) results in decreased embryo viability; further, histologically, placentas that are deficient in LIFR lack well-organized spongiotrophoblast and labyrinthine layers (8) and contain a reduced number of trophoblast giant cells (9). This indicates that LIF regulates trophoblast giant cell differentiation. On the other hand, the targeted disruption of SOCS3 resulted in midgestational lethality caused by placental defects (9, 10). Reduced numbers of spongiotrophoblast cells and increased numbers of trophoblast giant cells are observed in SOCS3-deficient placentas; further, SOCS3-deficient trophoblast stem cells differentiate more readily into giant cells (9), indicating that SOCS3 is a negative regulator of trophoblast giant cell differentiation. Further, a genetic reduction in either LIFR or LIF rescues placental defects and embryonic lethality in SOCS3-deficient mice (9, 11). These data demonstrate that SOCS3 is an essential negative regulator of LIFR signaling in the trophoblast giant cell differentiation. However, the physiological link between LIFR and SOCS3 in the trophoblast differentiation has not yet been clarified. In the present study, we used biochemical and genetic approaches to explore this link and the signaling mechanisms of the trophoblast giant cell differentiation.

RESULTS

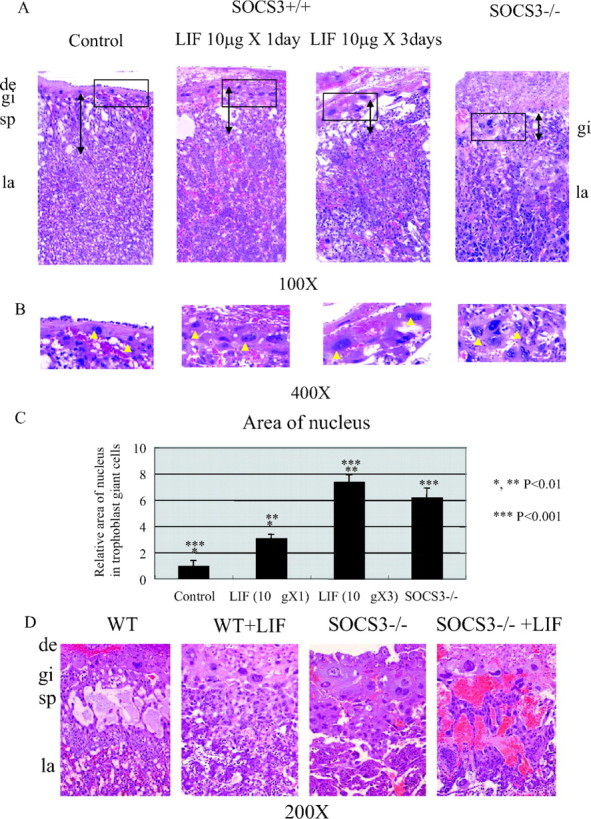

To assess the direct action of LIF on trophoblast giant cell differentiation in vivo, we analyzed the effect of LIF administration to pregnant mice. In this experiment, LIF was administered ip either 1 d [embryonic d 10.5 (E10.5)] or for 3 successive days (E8.5–10.5), and the placentas were analyzed on E11.5. The control placenta demonstrated a well-organized placental structure consisting of the trophoblast giant cell, spongiotrophoblast, and labyrinthine layers (Fig. 1, A and B, left). In contrast, the administration of LIF altered this organized structure. The nucleus size, which is an indicator of polyploidy in trophoblast giant cells, was enlarged (Fig. 1, A and B, middle); further, the thickness of the spongiotrophoblast layer was reduced (Fig. 1A, arrow) in a dose-dependent manner. These structural and cellular changes were comparable to those observed in SOCS3-deficient placentas (Fig. 1, A and B, right). The area of the nucleus of the trophoblast giant cells was increased depending on the LIF dose administered (Fig. 1C). These results strongly suggest that excessive LIF signaling stimulates trophoblast giant cell differentiation in vivo as observed in the SOCS3-deficient placenta. Further, we explored the effect of LIF administration on the SOCS3 heterozygous pregnant mice that were crossed with SOCS3 heterozygous male mice. As shown in Fig. 1D, LIF administration to SOCS3 heterozygous pregnant mice caused an enlargement of the nucleus of trophoblast giant cells and of the labyrinthine layer of the placenta in SOCS3-deficient mice. In addition, the placental structure of the labyrinthine layer was disrupted. Although, SOCS3-deficient embryos were viable on E11.5 as previously described (9), no viable embryos were observed in the LIF group (see Table 1 and Fig. 1D); this indicated that LIF administration enhances the abnormality in the SOCS3-deficient placentas and accelerates embryonic lethality.

Fig. 1.

LIF Administration to Wild-Type and SOCS3 Heterozygous Intercrossed Pregnant Mice

A, Administration of LIF to wild-type pregnant mice thinned the spongiotrophoblast layer (arrow) and increased the size of the nucleus of trophoblast giant cells. B, High magnification of the trophoblast giant cells clearly demonstrates that the administration of LIF caused enlargement of the nucleus. C, Quantification of the nuclear area in the trophoblast giant cells indicates significant increase in the area of the nucleus in the group administered LIF. In the group that was administered LIF for 3 d, the area of the nucleus of the trophoblast giant cells was comparable to that of the trophoblast giant cells in SOCS3-deficient placenta. D, The administration of LIF to SOCS3 heterozygous pregnant mice that were crossed with SOCS3 heterozygous male mice resulted in an enlargement of trophoblast giant cells in SOCS3-deficient placenta concomitant with the disruption of the labyrinthine layer. Three mice from each group were analyzed, and representative images are shown. Histological analysis of the other mice demonstrated similar results. WT, Wild type; de, decidva; gi, trophoblast giant cells; sp, spongiotrophoblast layer; la, labyrinthine layer.

Table 1.

LIF Treatment Accelerated Embryonic Lethality in SOCS−/− Embryo

| Genotyped on E11.5 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | +/+ | +/− | −/− | Viable−/−(%) | |||||

| Control | 88 | 19 (0) | 49 (0) | 20 (1) | 22% | ||||

| LIF treatment | 75 | 18 (7) | 51 (26) | 6 (6) (dead) | 0% | ||||

In SOCS3-deficient mice, until E11.5, SOCS3−/− embryos were viable. Strikingly, when LIF was administered to SOCS3 heterozygous pregnant mice, no viable SOCS3−/− embryos were detected on e11.5.

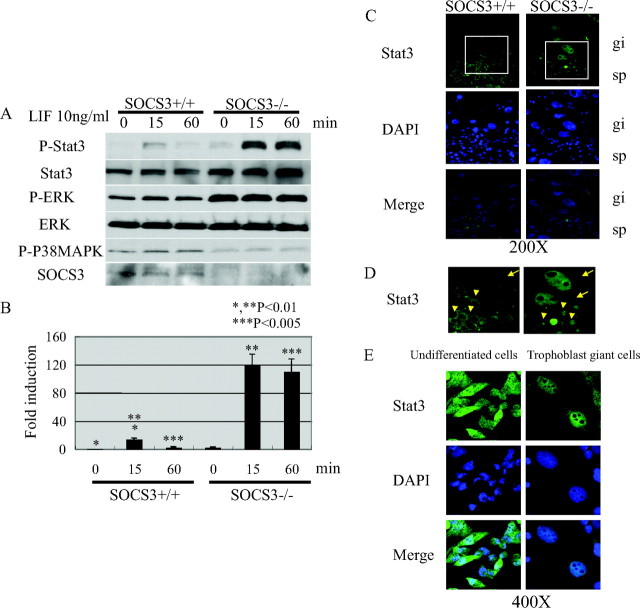

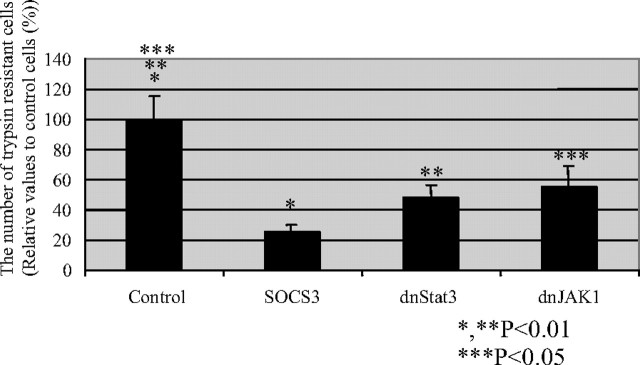

Next, we investigated the signaling links between LIFR and SOCS3 in vitro and in vivo. SOCS3−/− trophoblast stem cells derived from SOCS3−/− blastocysts were more prone to differentiate into trophoblast giant cells in vitro (9). We analyzed the LIF-dependent Stat3 phosphorylation in tyrosine residues in SOCS3+/+ and SOCS3−/− trophoblast stem cells (Fig. 2, A and B). LIF induced Stat3 phosphorylation in SOCS+/+ trophoblast stem cells at 15 min after stimulation. In contrast, Stat3 phosphorylation at 15 min was markedly enhanced and prolonged until 60 min in SOCS3−/− trophoblast stem cells. The level of phospho-ERK was increased and that of p38 was decreased constantly in SOCS3−/− trophoblast stem cells (Fig. 2A). In addition, Stat3 was predominantly localized in the nucleus in SOCS3-deficient trophoblast giant cells in the placenta, indicating that Stat3 is constitutively activated in SOCS3-deficient trophoblasts in vivo (Fig. 2, C and D). The cells from the choriocarcinoma-derived cell line Rcho-1 cells are suitable models of in vivo trophoblast stem cells, and they can be induced to exit the mitotic cell cycle and undergo endoreduplication concomitant with differentiation into trophoblast giant cells (12). As established by trophoblast stem cell model in vitro, the differentiation into trophoblast giant cells is induced by replacing the proliferation media (20% fetal calf serum) with the differentiation media [10% horse serum (HS)]. We analyzed the cellular localization of Stat3 during the trophoblast giant cell differentiation using Rcho-1 cells. Comparably, Stat3 was predominantly localized in the nucleus in the differentiated trophoblast giant cells, whereas Stat3 was localized both in the cytosol and the nucleus in the undifferentiated cells (Fig. 2E). To clarify the functional relevance of the Stat3 activation, either SOCS3, dominant negative Stat3 (dnStat3), or dominant negative JAK1 (dnJAK1) was expressed using an expression vector in Rcho-1 cells and subsequently, the effect on the differentiation of trophoblast giant cells was evaluated. Interestingly, the forced expression of SOCS3, dnStat3, and dnJAK1 significantly inhibited the trophoblast giant cell differentiation (Fig. 3). These data suggest that the LIF-JAK1-Stat3-SOCS3 cascade plays an important role in the trophoblast giant cell differentiation.

Fig. 2.

Altered LIF Signaling in SOCS3−/− Trophoblast Stem Cells Derived from SOCS3−/− Blastocyst

A, In SOCS3−/− trophoblast stem cells, enhanced and prolonged phosphorylation of Stat3 on LIF stimulation was observed. ERK was constitutively phosphorylated and p38 phosphorylation was diminished in SOCS3−/− trophoblast stem cells. B, Quantitative analysis of Stat3 phosphorylation from three independent experiments. The intensity of P-Stat3 was normalized by that of Stat3. C, Stat3 was activated in the trophoblast giant cells (arrows) and trophoblasts (arrowheads) in the spongiotrophoblast layer in SOCS3-deficient placenta. The nuclear localization of Stat3 indicates Stat3 activation. D, An enlarged image of the indicated square in panel C. E, In Rcho-1 cells, Stat3 was activated in trophoblast giant cells but not in undifferentiated stem cells. DAPI, 4′,6-Diamino-2-phenylindole; P-ERK, phospho-ERK; P-Stat, phospho-Stat; P-P38MAPK, phospho-P38MAPK; gi, trophoblast giant cells; sp, spongiotrophoblast layer.

Fig. 3.

JAK1-Stat3 Signaling Regulates Trophoblast Giant Cell Differentiation

In Rcho-1 cells, the forced expression of dnJAK1, dnStat3, and SOCS3 significantly reduced the number of differentiated trophoblast giant cells, which were evaluated to be trypsin resistant. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown. The other experiments showed similar results.

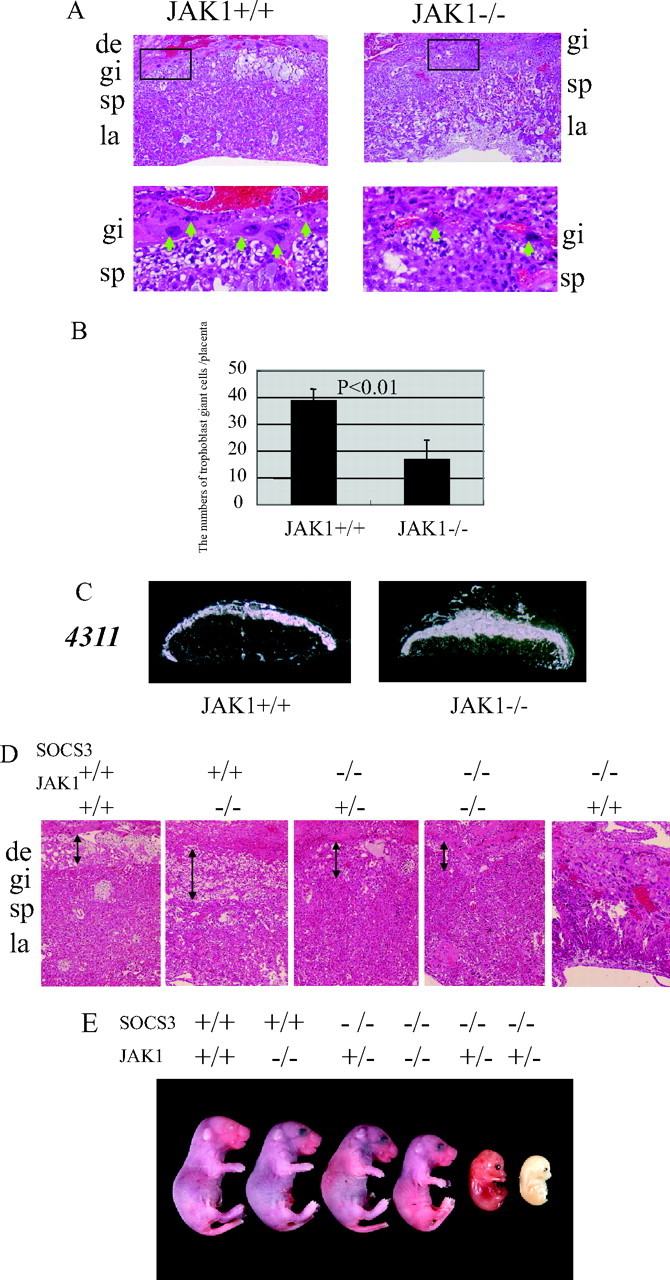

To elucidate the physiological role of JAK1 in the trophoblast giant cell differentiation, we analyzed JAK1-deficient placentas. JAK1-deficient mice are runted at birth and die perinatally (4). In JAK1-deficient placentas at E12.5, trophoblast giant cells were smaller in size, and the number was decreased compared with JAK1+/+ placentas (Fig. 4, A and B), indicating that JAK1 plays an important role in the trophoblast giant cell differentiation in vivo. The expression of the stem cell marker 4311 in spongiotrophoblasts was markedly increased in JAK1-deficient placentas, indicating impaired differentiation from precursor cells to trophoblast giant cells. Finally, we explored whether the genetic reduction of JAK1 could rescue the placental defects and embryonic lethality in SOCS3-deficient mice. We crossed SOCS3 and JAK1 double-heterozygous mice to obtain embryos that would be deficient in both genes. Because of the perinatal lethality in JAK1-deficient mice, embryos from the cross were recovered at term (E18.5) by cesarean section and analyzed. As illustrated in Table 2 and Fig. 4, among the embryos that were wild-type for JAK1, no viable SOCS3-deficient embryos were obtained. However, among the embryos that were either heterozygous or homozygous for JAK1, we found SOCS3-deficient embryos in expected numbers by Mendelian ratio at term (Table 2), although two embryos in JAK1 heterozygous background were dead. This is striking because no SOCS3-deficient embryos were obtained in our analysis of 161 embryos at term. Further, the abnormality in SOCS3-deficient placentas was also restored (Fig. 4D). The functional rescue of the placenta was revealed by the comparable development of SOCS3-deficient embryos at term (E18.5) (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

JAK1 Plays an Essential Role in Trophoblast Giant Cell Differentiation

A, In JAK1-deficient placentas, the size and number of trophoblast giant cells were decreased. B, The number of trophoblast giant cells was significantly reduced in JAK-1 deficient placentas. C, The expression of the stem cell marker 4311 in the spongiotrophoblast layer was markedly enhanced in JAK1-deficient placentas. D, The abnormality in the SOCS3-deficient placentas was restored in mice with the JAK1+/− or −/− back ground. The placentas at term (E18.5) are shown in the case of the mice with SOCS3−/−, JAK1+/+ (E12.5). E, Viable SOCS3−/− embryos were detected at term (E18.5) in the JAK1+/− or −/− background, clearly indicating the functional rescue of SOCS3-deficient placentas. de, Decidva; gi, trophoblast giant cells; sp, spongiotrophoblast layer; la, labyrinthine layer.

Table 2.

The JAK1−/− and +/− Backgrounds Rescued Placental Defects and Embryonic Lethality in SOCS3-Deficient Mice

| SOCS3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | +/− | −/− | |||||

| JAK1 | +/+ | 4 | 7 | 0 | |||

| +/− | 11 | 20 | 10 (2) (dead) | ||||

| −/− | 3 | 5 | 4 | ||||

| SOCS3 heterozygous intercross | 55 | 106 | 0 | ||||

SOCS3-deficient embryos died around E12.5–E15.5, and no viable embryos were detected at term; however, viable SOCS3−/− embryos were detected at term (E18.5) in the JAK1−/− and +/− background.

DISCUSSION

It has already been reported that the deletion of SOCS3 causes an embryonic lethality because of placental failure (9, 10) and genetic reduction of LIF or LIF receptor (LIFR) in SOCS3-deficient mice rescues placental defects and embryonic lethality, indicating that SOCS3 is an essential inhibitor of LIFR signaling (9, 11). In the placenta, SOCS3 negatively regulates trophoblast giant cell differentiation, and the deletion of SOCS3 results in an increased number of trophoblast giant cells and a decreased number of precursor cells in the spongiotrophoblast layer (9). It has also been reported that the supply of trophoblast stem cells into SOCS3-deficient blastocysts rescues the lethality of these embryos, suggesting that the excessive trophoblast giant cell differentiation results in a lack of stem cells in SOCS3-deficient placentas (13). These results indicate that the trophoblast giant cell differentiation is positively regulated by LIFR signaling and negatively regulated by SOCS3. In the present study, we demonstrate that LIF administration induced trophoblast giant cell differentiation and accelerated the embryonic lethality in SOCS3-deficient mice concomitant with the enhancement of trophoblast differentiation. Histological analysis of the placentas of SOCS3−/− embryos after LIF treatment demonstrated severe disruption in the labyrinthine layer that is essential for embryonic growth and survival. It is speculated that these histological changes caused enhanced embryonic lethality in SOCS3−/− mice administered LIF. These data indicate that LIF stimulates trophoblast giant cell differentiation and SOCS3 deficiency enhances LIF signaling in vivo.

Trophoblast giant cells invade the deciduas of the uterus. Trophoblast giant cells are large, highly polyploid cells that are formed through the process of endoreduplication (14). The differentiation of trophoblast giant cells is induced by the withdrawal of stem cell maintaining-factors and promoted by retinoic acid, PTHrP, nerve growth factor, and LIF treatment (14). However, the downstream signaling in this process has not been fully elucidated. LIF stimulates the JAK1-Stat3 pathway (4), and knockdown of Stat3 in the choriocarcinoma cell line Jeg3 results in the loss of LIF-induced invasion; this suggests that the JAK1-Stat3 signaling regulates trophoblast giant cell differentiation and function. In the present study, we demonstrated that in SOCS3-deficient trophoblasts, the LIF-induced activation of Stat3 was enhanced in vitro and in vivo. Further, in Rcho-1 cells, Stat3 was activated during trophoblast giant cell differentiation. Notably, the forced expression of SOCS3, dnStat3, and dnJAK1 suppresses trophoblast giant cell differentiation, suggesting that the LIFR-JAK1-Stat3 pathway plays an important role in trophoblast giant cell differentiation. Stat3 is known to be an oncogenic transcriptional factor because of its ability to regulate the expression of proteins that enhance tumor cell migration and invasion (15). It is intriguing that trophoblast giant cells have functions similar to those of invading tumor cells. It is suggested that Stat3 plays a common role in the migration and invasion of both trophoblast giant cells and tumor cells. In SOCS3-deficient trophoblast stem cells, augmented ERK activation and diminished p38 activation were observed. These changes were caused by the deletion of SOCS3 and were LIF independent, suggesting that SOCS3 may affect trophoblast differentiation via these pathways that are independent of LIF signaling.

JAK1-deficient mice are runted at birth and die perinatally; however, the placental defects have not been reported. We found that in JAK1-deficient placentas, the number of trophoblast giant cells was significantly decreased and that of the precursor cells was increased. These data indicate that JAK1 is an important regulator of trophoblast giant cell differentiation. Further, the labyrinthine layer that is essential for the growth of embryos was substantially disorganized, suggesting that the growth failure in JAK1-deficient embryos was caused by these placental defects. The abnormality in JAK1-deficient placentas was indistinguishable from that in LIFR-deficient placentas (9), suggesting that JAK1 exerts its function in the downstream of LIFR. Finally, we demonstrate that the genetic reduction in JAK1 rescued placental defects and embryonic lethality in SOCS3-deficient mice. These results clearly indicate that SOCS3 is a negative regulator of JAK1 signaling in the placenta in vivo.

In summary, we demonstrate the link between LIFR and SOCS3. The LIFR signaling is finely coordinated by JAK1, Stat3, and SOCS3 and regulates trophoblast giant cell differentiation. Further, these results establish that LIF-JAK1-Stat3-SOCS3 signaling is an essential pathway for the regulation of trophoblast giant cell differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

The generation of SOCS3-disrupted mice and JAK1-disrupted mice has previously been described (9, 16). Genotyping was performed by PCR using tail biopsies. The phenotypes were analyzed in mixed 129/Sve C57Bl/6 background. For the LIF administration experiments, three mice for each group of 4- to 5-month-old mixed 129/Sve C57Bl/6 wild-type female mice were used. Recombinant murine LIF was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA).

Cell Culture

The Rcho-1 cell line derived from a rat choriocarcinoma was obtained from M. Soares. The cells were maintained in NCTC135 medium supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml sodium pyruvate, 2 mm glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, and 20% fetal calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Inc., Logan, UT). At confluence, cells were cultured in NCTC135 + 10% HS (Hyclone) to induce giant cell differentiation as previously described (9, 17). The constructs of dnJAK1, SOCS3, and dnStat3 were previously described (9, 18). The plasmid was transfected with a green fluorescent protein-expressing vector using Lipofectamine plus reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Giant cell differentiation assays were performed 72 h after transfection as previously described (19). Briefly, 2 d after the induction in 10% HS, stem cells were removed by trypsinization (0.25% trypsin and 1 mm EDTA). The cells were incubated with trypsin and EDTA for 5 min and washed with PBS twice, after which the green fluorescent protein-positive adherent cells for each condition were counted in 20 random high-magnification fields. SOCS3-deficient trophoblast stem cells were established as previously described (9, 20). The cells were maintained on mouse embryo fibroblasts in the presence of fibroblast growth factor 4 and heparin. When the cells were stimulated by LIF, cells were cultured without mouse embryo fibroblasts in the presence of fibroblast growth factor 4 and heparin.

Histological Analysis, in Situ Hybridization, and Immunofluorescence

Freshly isolated placentas were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned (4 mm). The sections were analyzed by hematoxylin/eosin staining. RNA in situ hybridization was carried out as described elsewhere (9) using [γ-33P]uridine triphosphate-labeled antisense cRNA probes. The nuclear area of the trophoblast giant cells was evaluated using Image J software as previously described (21). For the evaluation of the numbers of giant cells in placentas, five wild-type and five JAK1-deficient placentas were used. For immunofluorescence analysis, placental sections or Rcho cells on coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized in PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Sections were incubated with anti-Stat3 antibody (1:100) as the primary antibody and antirabbit-fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibody as the secondary antibody. Sections were subsequently washed, counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1:1000, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), mounted, and visualized by using Leica DM-IRBE confocal microscopy (Leica Corp., Deerfield, IL).

Western Blot Analysis

Western blotting analysis was performed as described elsewhere (9, 22). Equal amounts of protein from each of the lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE using 12% separating gels. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and the membranes were incubated with indicated antibody after blocking. For primary antibodies, anti-pStat3 (1:500), anti-Stat3 (1:500), anti-pERK (1:1000), anti-ERK (1:1000), and anti-pp38 (1:500) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) were used. Anti-SOCS3 antibody was previously described (9). The membranes were washed using Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit secondary antibody. The signal was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

Statistical Analysis

Values were reported as the mean ± sem, and significant differences between values were determined by Student’s t test or ANOVA. Results are from three different experiments performed independently unless stated otherwise.

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratory members for their helpful discussions and advice; Animal Resources Center members Lisa Emmons, John Raucci, Christie Nagy, and John Swift for assistance; and Catriona McKay, Kristen Rothammer, Neena Carpino, Linda Snyder, and Juliana Nune for technical support. Y.T. especially thanks H. Iwakabe for his support.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the Uehara Memorial Foundation (to Y.T), a Cancer Center CORE grant (to J.N.I), and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online May 1, 2008

Abbreviations: dnJAK, Dominant-negative JAK; dnStat, dominant-negative Stat; E10.5, embryonic d 10.5; HS, horse serum; JAK1, Janus kinase 1; LIF, leukemia-inhibitory factor; LIFR, LIF receptor; SOCS3, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3; Stat, signal transducer and activator of transcription.

References

- 1.Simmons DG, Cross JC 2005. Determinants of trophoblast lineage and cell subtype specification in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol 284:12–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemberger M 2008. IFPA Award in Placentology Lecture. Characteristics and significance of trophoblast giant cells. Placenta 29S:4–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Stahl N, Boulton TG, Farruggella T, Ip NY, Davis S, Witthuhn BA, Quelle FW, Silvennoinen O, Barbieri G, Pellegrini S 1994. Association and activation of Jak-Tyk kinases by CNTF-LIF-OSM-IL-6β receptor components. Science 263:92–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodig SJ, Meraz MA, White JM, Lampe PA, Riley JK, Arthur CD, King KL, Sheehan KC, Yin L, Pennica D, Johnson Jr EM, Schreiber RD 1998. Disruption of the Jak1 gene demonstrates obligatory and nonredundant roles of the Jaks in cytokine-induced biologic responses. Cell 93:373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parganas E, Wang D, Stravopodis D, Topham DJ, Marine JC, Teglund S, Vanin EF, Bodner S, Colamonici OR, van Deursen JM, Grosveld G, Ihle JN 1998. Jak2 is essential for signaling through a variety of cytokine receptors. Cell 93:385–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starr R, Willson TA, Viney EM, Murray LJ, Rayner JR, Jenkins BJ, Gonda TJ, Alexander WS, Metcalf D, Nicola NA, Hilton DJ 1997. A family of cytokine-inducible inhibitors of signalling. Nature 387:917–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart CL, Kaspar P, Brunet LJ, Bhatt H, Gadi I, Kontgen F, Abbondanzo SJ 1992. Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature 359:76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware CB, Horowitz MC, Renshaw BR, Hunt JS, Liggitt D, Koblar SA, Gliniak BC, McKenna HJ, Papayannopoulou T, Thoma B, Cheng L, Donovan PJ, Peschonl JJ, Bartlett PF, Willis CR, Wright BD, Carpenter MK, Davison BL, Gearing DP 1995. Targeted disruption of the low-affinity leukemia inhibitory factor receptor gene causes placental, skeletal, neural and metabolic defects and results in perinatal death. Development 121:1283–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi Y, Carpino N, Cross JC, Torres M, Parganas E, Ihle JN 2003. SOCS3: an essential regulator of LIF receptor signaling in trophoblast giant cell differentiation. EMBO J 22:372–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts AW, Robb L, Rakar S, Hartley L, Cluse L, Nicola NA, Metcalf D, Hilton DJ, Alexander WS 2001. Placental defects and embryonic lethality in mice lacking suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:9324–9329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robb L, Boyle K, Rakar S, Hartley L, Lochland J, Roberts AW, Alexander WS, Metcalf D 2005. Genetic reduction of embryonic leukemia-inhibitory factor production rescues placentation in SOCS3-null embryos but does not prevent inflammatory disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:16333–16338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahgal N, Canham LN, Canham B, Soares MJ 2006. Rcho-1 trophoblast stem cells: a model system for studying trophoblast cell differentiation. Methods Mol Med 121:159–178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi Y, Dominici M, Swift J, Nagy C, Ihle JN 2006. Trophoblast stem cells rescue placental defect in SOCS3-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 281:11444–11445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cross JC, Nakano H, Natale DR, Simmons DG, Watson ED 2006. Branching morphogenesis during development of placental villi. Differentiation 74:393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang S 2007. Regulation of metastases by signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling pathway: clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res 13:1362–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sexl V, Kovacic B, Piekorz R, Moriggl R, Stoiber D, Hoffmeyer A, Liebminger R, Kudlacek O, Weisz E, Rothammer K, Ihle JN 2003. Jak1 deficiency leads to enhanced Abelson-induced B-cell tumor formation. Blood 101:4937–4943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faria TN, Soares MJ 1991. Trophoblast cell differentiation: establishment, characterization, and modulation of a rat trophoblast cell line expressing members of the placental prolactin family. Endocrinology 129:2895–2906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakajima H, Ihle JN 2001. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid differentiation through CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein ε. Blood 98:897–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cross JC, Flannery ML, Blanar MA, Steingrimsson E, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Rutter WJ, Werb Z 1995. Hxt encodes a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor that regulates trophoblast cell development. Development 121:2513–2523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka S, Kunath T, Hadjantonakis AK, Nagy A, Rossant J 1998. Promotion of trophoblast stem cell proliferation by FGF4. Science 282:2072–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmons DG, Fortier AL, Cross JC 2007. Diverse subtypes and developmental origins of trophoblast giant cells in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol 304:567–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi Y, Shirono H, Arisaka O, Takahashi K, Yagi T, Koga J, Kaji H, Okimura Y, Abe H, Tanaka T, Chihara K 1997. Biologically inactive growth hormone caused by an amino acid substitution. J Clin Invest 100:1159–1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]