Abstract

Leptin is an adipokine that regulates food intake and energy expenditure by activating its hypothalamic leptin receptor (LR). Members of the insulin receptor substrate (IRS) family serve as adaptor proteins in the signaling pathways of several cytokines and hormones and a role for IRS2 in central leptin physiology is well established. Using mammalian protein-protein interaction trap (MAPPIT), a cytokine receptor-based two-hybrid method, in the N38 hypothalamic cell line, we here demonstrate that also IRS4 interacts with the LR. This recruitment is leptin dependent and requires phosphorylation of the Y1077 motif of the LR. Domain mapping of IRS4 revealed the critical role of the pleckstrin homology domain for full interaction. In line with its function as an adaptor protein, IRS4 interacted with the regulatory p85 subunit of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, phospholipase Cγ, and the suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) family members SOCS2, SOCS6, and SOCS7 and thus can modulate LR signaling.

THE CYTOKINE-LIKE hormone leptin, product of the ob gene, is secreted mainly by white adipose tissue and signals body energy stores to the brain. It binds to the leptin receptor (LR) on hypothalamic neurons that are critically involved in body weight homeostasis by balancing food intake and energy expenditure (1, 2). Beside this central effect on weight regulation, leptin is also involved in a wide range of other physiological functions including reproduction, bone formation, growth, immune regulation, and angiogenesis.

The LR, product of the db gene, is a member of the class I cytokine receptor family (3). Like ob/ob mice, db/db mice display obesity, hyperphagia, and endocrine dysfunction (4, 5, 6). The intracellular domain of the LR contains a Box1 motif, responsible for constitutive association of the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) tyrosine kinase, and three conserved tyrosines (positions Y985, Y1077, and Y1138 in the murine LR). Upon leptin binding, the JAKs activate each other through cross-phosphorylation and phosphorylate the tyrosine residues in the intracellular domain. The membrane distal tyrosine Y1138 recruits signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) molecules through their src homology 2 (SH2) domain (7, 8). Phosphorylated STAT3 proteins translocate as dimers to the nucleus to activate gene transcription. One of the immediate early response-induced genes, activated in the hypothalamus, is suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), a negative regulator of leptin signaling (9, 10). SOCS3 associates predominantly with the pY985 motif in the LR. Weak interaction at position pY1077 may explain its additive effect on inhibition of LR signaling (11, 12).

In addition to STAT3 activation, leptin regulates other key signaling pathways. The membrane proximal tyrosine Y985 of the LR is a recruitment site for SH2-containing phosphatase 2 (SHP2) leading to activation of the MAPK pathway, although an additional pathway for activation of this signaling cascade directly by JAK2 has been suggested (13). ERK 1/2 is phosphorylated in response to leptin in a number of tissues and cell lines (14, 15). Leptin also activates Jun N-terminal kinase (c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase), p38 MAPK (16, 17), and phosphodiesterase 3B (PDE3B) leading to a decrease in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels (18). Recently, an inhibitory effect of leptin on hypothalamic AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity was reported. AMP-activated protein kinase is proposed to act as a fuel gauge to an intracellular energy sensor cascade, and its activation in the hypothalamus promotes food intake (19).

Insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins play a central role in signal transduction by insulin, IGF-I, and a growing number of cytokines (20). So far, six IRS proteins have been identified (IRS1–6) (21, 22). They serve as multi-adaptor proteins and are phosphorylated on multiple tyrosine residues to mediate SH2-protein recruitment and downstream signaling. Leptin was reported to induce phosphorylation of two members of the IRS family, IRS1 and IRS2 (23), leading to activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) (24, 25). In addition to other defects, IRS2−/− mice display increased feeding and decreased metabolic rate with increased adiposity and circulating leptin levels, suggesting functional leptin resistance (26, 27). IRS4 is highly expressed in the hypothalamus (28, 29), and mice lacking IRS4 exhibit mild defects in growth, reproduction, and glucose homeostasis (30), as is also seen in several other models for leptin resistance. In this study, we analyzed the interaction of IRS4 with the LR using the mammalian protein-protein interaction trap (MAPPIT) strategy and provide several lines of evidence for a function of IRS4 in LR signaling.

RESULTS

Design of MAPPIT Experiments

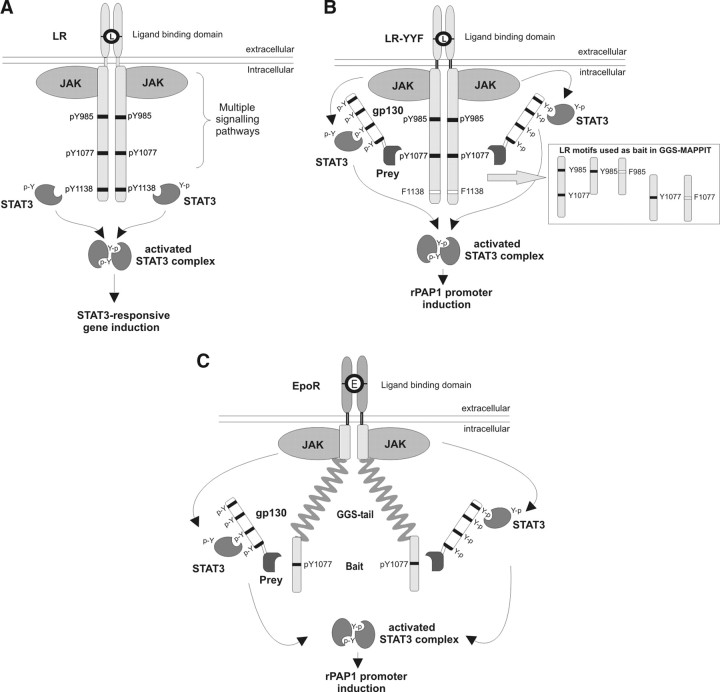

A general overview of signaling through the LR is shown in Fig. 1A. With MAPPIT we developed a new method to analyze protein-protein interactions in mammalian cells (31). The MAPPIT approach allows direct analysis of interactions with the mouse LR (mLR) by a simple Y1138F mutation of the STAT3-recruitment motif (LR-YYF). The LR-YYF thus serves as MAPPIT bait that very closely mimics the natural LR configuration. MAPPIT prey constructs are composed of a prey polypeptide fused to a part of the gp130 chain carrying four STAT3 recruitment sites. Coexpression of interacting bait and prey leads to functional complementation of STAT3 activity that can be measured with the STAT3-responsive rat pancreatitis-associated protein I (rPAP1) promoter-luciferase reporter (Fig. 1B). Intrinsic to this strategy, both modification-independent and tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent interactions can be detected.

Fig. 1.

MAPPIT Experimental Setup

A, Overview of LR signaling. For details, we refer to the introductory section. B, The MAPPIT technique allows direct analysis of interactions with the LR by simple mutation of the Y1138 STAT3 recruitment motif to phenylalanine (LR-YYF). Tyrosine residues are represented by a black line, phenylalanine mutants by a white line. MAPPIT prey constructs are composed of a prey polypeptide fused to a part of the gp130 chain carrying four STAT3 recruitment sites. Coexpression of interacting bait and prey leads to functional complementation of STAT3 activity that can be measured with the STAT3-responsive rat pancreatitis-associated protein I (rPAP1) promoter-luciferase reporter. C, GGS-MAPPIT. To monitor interactions with isolated tyrosine motifs of the LR, we developed the GGS-MAPPIT configuration whereby the cytosolic domain of the LR, following the JAK2 interaction site, is replaced by an array of 60 Gly-Gly-Ser (GGS) repeats. A GGS bait consists of the extracellular part of the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) fused to the JAK2 interaction site of the LR and a large array of GGS repeats, with the C-terminally attached LR Y985 and/or Y1077 motif or the Y to F mutant of those motifs (see box in B). This same configuration was also used for the IRS4 bait. The different protein domains in A–C are not drawn to scale.

To monitor interactions with isolated tyrosine motifs of the mLR, we developed the GGS-MAPPIT configuration whereby the cytosolic domain of the mLR, following the JAK2 recruitment site, is replaced by an array of Gly-Gly-Ser (GGS) repeats (Fig. 1C). GGS triplet repeats are often used as hinge sequences for their known structural flexibility. Here, the mLR-GGS baits consist of the extracellular part of the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) fused to the JAK2 interaction site of the mLR and an array of 60 GGS repeats, with a C-terminally attached mLR portion encompassing the Y985 and/or Y1077 motifs (32).

IRS4 Interacts with the LR

Leptin activates the PI3K pathway through the IRS1 and IRS2 adaptor proteins of the IRS family (23). Using MAPPIT, we examined whether IRS4 could interact with the LR. All MAPPIT experiments were performed in a leptin-responsive mouse hypothalamic N38 cell line (33), providing a more physiological setting compared with the HEK293T cell line that is more generally used for MAPPIT experiments.

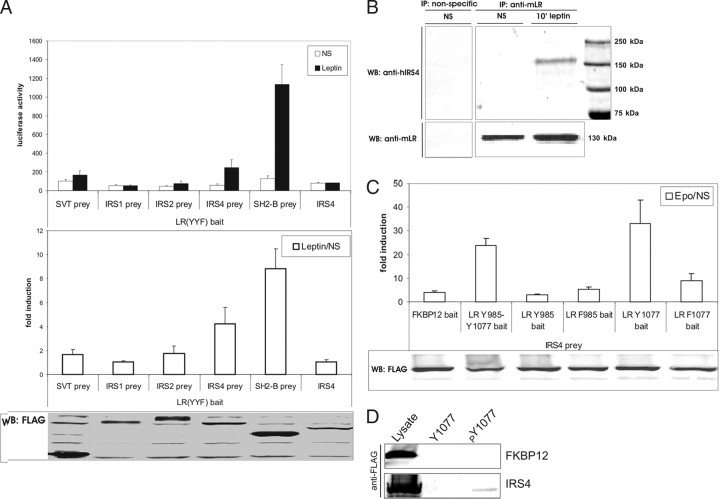

To determine interaction with the LR, the IRS4 prey fusion protein was transiently coexpressed with the LR(YYF) mutant and the luciferase reporter construct in N38 cells. The endogenous LR levels in N38 cells were too low to give rise to background signaling after leptin stimulation. In contrast to the IRS1 and IRS2 prey, the IRS4 prey clearly interacted with the LR(YYF) (Fig. 2A). IRS4 itself could not bind STAT3, because IRS4 alone (without the STAT3 recruitment sites of gp130) did not lead to luciferase induction. SV40 large T protein (SVT) and SH2-B, a known JAK2 binder, were used as negative and positive prey controls. Of note, positive SH2-B detection implies that the attached bait does not interfere with the MAPPIT readout, e.g. by blocking JAK2 activation. In these, and the experiments described below, background signaling and functional bait expression were analyzed with the SVT and SH2-B prey, respectively. Expression of the FLAG-tagged preys was revealed by immunoblotting using an anti-FLAG antibody. Similar results were obtained in HEK293T cells (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

IRS4 Interacts with the LR

A, LR-MAPPIT. N38 cells were transiently cotransfected with plasmids encoding the mutant LR-YYF variant and different IRS prey constructs, combined with the pXP2d2-rPAP1-luci reporter. The SVT and SH2-B preys were used to determine background signaling and functional bait expression, respectively. An IRS4 construct without the STAT3 recruitment sites (of gp130) was used to determine the intrinsic STAT3 binding capacity of IRS4. The transfected cells were either stimulated with leptin for 24 h or were left untreated (NS, not stimulated). Luciferase measurements were performed in quadruplicate and are expressed as luciferase activity + sd (top graph) or as mean fold induction (leptin/NS) + sd (bottom graph). Expression of the FLAG-tagged prey proteins was verified on lysates using anti-FLAG antibody. Similar results were obtained of three independent experiments. B, Endogenous LR-IRS4 interaction. A monoclonal rat antimouse LR antibody was used to pull down the LR and its associated proteins from a protein extract made from HEK293 cells stably expressing the mLR. Only in the leptin-stimulated cells, IRS4 (±160 kDa) was co-immunoprecipitated with the mLR (upper panel). The first lane shows a mock precipitation using a normal rat IgG antibody as a nonspecific control. After stripping, the blots were reprobed with a goat anti-mLR antibody (K-20) (bottom panel). The immunoblot shown is representative for three separate experiments. WB, Western blot. C, GGS-MAPPIT. N38 cells were transiently cotransfected with plasmids encoding the chimeric GGS bait constructs with the different LR motifs (see box in Fig. 1B) or with the FKBP12 control bait, and the IRS4 prey construct, together with the pXP2d2-rPAP1-luci reporter. The transfected cells were either stimulated with erythropoietin (Epo) for 24 h or were left untreated (NS, not stimulated). Luciferase measurements were performed in quadruplicate and are expressed as mean fold induction (Epo/NS) + sd. Expression of the FLAG-tagged prey proteins was verified on lysates using anti-FLAG antibody. Background signaling and expression of the bait constructs were analyzed using the SVT and SH2-B prey, respectively (data not shown). Similar results were obtained from five independent experiments. D, (Phospho)peptide affinity chromatography. FLAG-tagged FKBP12 or IRS4 were expressed in HEK293 cells and lysates were incubated with phosphorylated (pY1077) or nonphosphorylated (Y1077) peptides corresponding to the LR Y1077 motif. Immunoblotting with anti-FLAG revealed specific interaction of IRS4 with the phosphorylated Y1077 motif. FKBP12 was used as a negative control.

To provide evidence for interaction of the endogenous proteins, we conducted coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments using HEK293 cells stably expressing low levels of the mLR. HEK293 cells may be of neuronal origin (34) and express IRS4 (35). Complexes were precipitated from cell lysates using a rat anti-mLR antibody, were resolved on a polyacrylamide gel, and were assayed for the presence of human IRS4 through Western blot analysis with an anti-IRS4 antibody. In leptin-stimulated HEK293 cells, IRS4 was clearly able to interact with the mLR, whereas no binding was observed in untreated cells (Fig. 2B). Because a similar co-IP experiment for IRS2 did not show an interaction with the LR (data not shown), we focused in this study on IRS4. A mock precipitation performed by using normal rat IgG generated no immunoreactive signal. Together, these findings establish the leptin-dependent interaction between IRS4 and the LR.

To examine the interaction of IRS4 with the mLR in more detail, we used GGS-MAPPIT with mLR motifs encompassing Y985 and/or Y1077 (Fig. 1C). mLR motifs with a tyrosine to phenylalanine mutation were used to analyze the phosphorylation dependency of the interaction. A mock GGS-FKBP12 bait was used as negative control. The IRS4 prey interacted with the GGS-LR Y1077 motif but not with the GGS-LR F1077, GGS-LR Y985, or GGS-LR F985 motifs, demonstrating the phosphorylation-dependent binding of IRS4 with the Y1077 motif of the LR (Fig. 2C). This observation was confirmed using (phospho)peptide affinity chromatography (Fig. 2D). FLAG-tagged FKBP12 or IRS4 proteins were expressed in HEK293T cells, and total cell lysates were incubated with biotinylated peptides encompassing the phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated LR Y1077 motif to verify (phospho)tyrosine-specific association. IRS4 interacted only with the phosphorylated Y1077 motif, confirming its specific phosphorylation-dependent interaction with the LR. FKBP12 was used as a negative control.

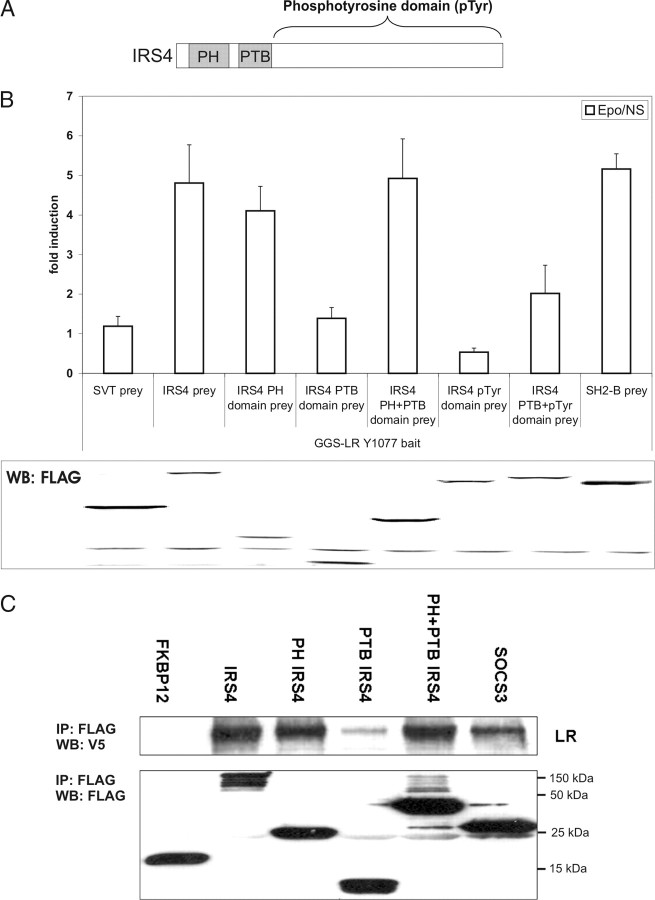

The Pleckstrin Homology (PH) Domain of IRS4 Is Sufficient for LR Binding

IRS4 follows the typical IRS domain structure with an N-terminal PH domain followed by a phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domain and a large C-terminal part with several putative tyrosine-phosphorylation sites (pTyr) (Fig. 3A) (36). Using subdomains of IRS4 as preys, we next determined which parts of IRS4 were required for mLR binding. A GGS-LR Y1077 bait was coexpressed with different IRS4 subdomain preys in N38 cells. The PH domain alone and the combination of the PH and the PTB domain of IRS4 show clear interaction with the GGS-LR Y1077 bait. The isolated PTB or pTyr domains, or their combination, did not lead to any significant luciferase activity (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

The PH Domain of IRS4 Is Sufficient for LR Binding

A, Schematic structure of IRS4. B, GGS-MAPPIT. N38 cells were transiently cotransfected with plasmids encoding the chimeric GGS-LR Y1077 bait and the full-length IRS4 prey or different subdomain IRS4 preys, combined with the pXP2d2-rPAP1-luci reporter. The SVT and SH2-B preys were used to determine background signaling and functional bait expression, respectively. The transfected cells were either stimulated with erythropoietin (Epo) for 24 h or left untreated (NS, not stimulated). Luciferase measurements were performed in quadruplicate and are expressed as mean fold induction (Epo/NS) + sd. Expression of the FLAG-tagged prey proteins was verified on lysates using anti-FLAG antibody. Results are representative for four independent experiments. C, Co-IP. HEK293T cells were transiently cotransfected with a V5-tagged LR construct and a FLAG-tagged interaction partner construct and stimulated with leptin. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-FLAG antibody and assayed for the presence of the LR by Western blotting (WB) with an anti-V5 antibody. After stripping, the blot was reprobed with an anti-FLAG antibody to ensure equal expression of the different IRS4 constructs. FKBP12 and SOCS3 were used as a negative and positive control, respectively.

Similar results were obtained by co-IP experiments (Fig. 3C). HEK293T cells were cotransfected with a V5-tagged mLR construct and FLAG-tagged IRS4 constructs and were stimulated with leptin. After immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody, the precipitates were separated on a polyacrylamide gel and assayed for the presence of the mLR by immunoblotting with an anti-V5 antibody. FKBP12 and the known mLR binder SOCS3 were used as a negative and positive controls, respectively (11, 12). Next to the MAPPIT findings, these co-IP results demonstrate that the IRS4 PH domain is sufficient for mLR binding.

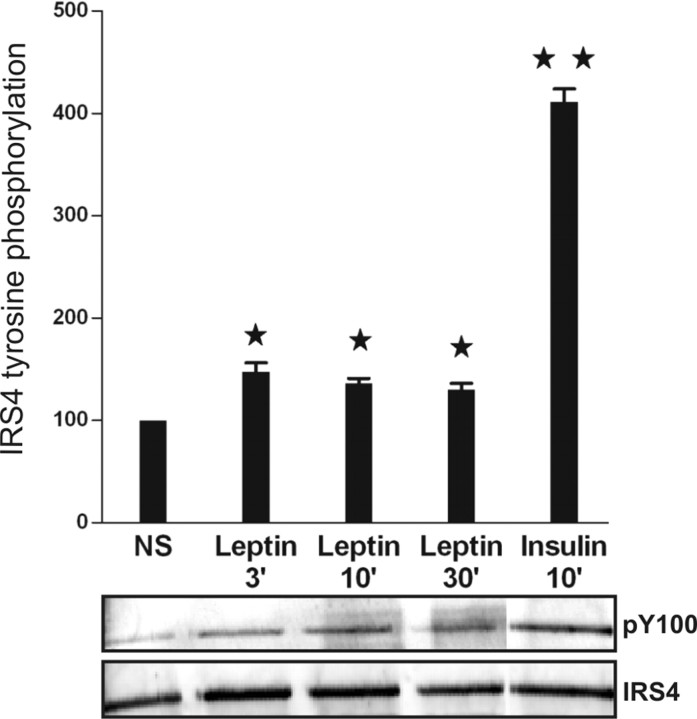

Leptin Induces IRS4 Tyrosine Phosphorylation

IRS4 was previously reported to become tyrosine phosphorylated in insulin-treated HEK293 cells (35, 37). To analyze IRS4 tyrosine phosphorylation, we immunoprecipitated IRS4 from HEK293 cells stably expressing the murine LR after stimulation with leptin (100 ng/ml) or insulin (100 nm). We observed strong (about 4-fold, P < 0.01) IRS4 tyrosine phosphorylation by insulin and also a weaker 1.5-fold (P < 0.05), but consistent IRS4 tyrosine phosphorylation after leptin stimulation (Fig. 4). It thus appears that the LR complex couples to IRS4 but is less potent than the insulin receptor in phosphorylating this adaptor. However, it is unclear at present whether similar or different sets of tyrosine motifs are phosphorylated upon insulin vs. leptin treatment and whether this may affect the detection using the pY100 antibody.

Fig. 4.

Leptin Induces IRS4 Tyrosine Phosphorylation

HEK293 cells, stably expressing the murine LR, were stimulated with leptin (100 ng/ml) or insulin (100 nm) for 0–30 min followed by cell lysis, immunoprecipitation with an anti-IRS4 antibody, and immunoblotting for phosphotyrosine (pY100). Quantification of the tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS4 was performed using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor), and the summary of four independent experiments is shown in the bar graph. Results are expressed as mean fold induction (Stim/NS) + sd [unpaired Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05 vs. not stimulated (NS); **, P < 0.01 vs. NS]. WB, Western blot.

IRS4 Acts as a Multi-Adaptor Protein

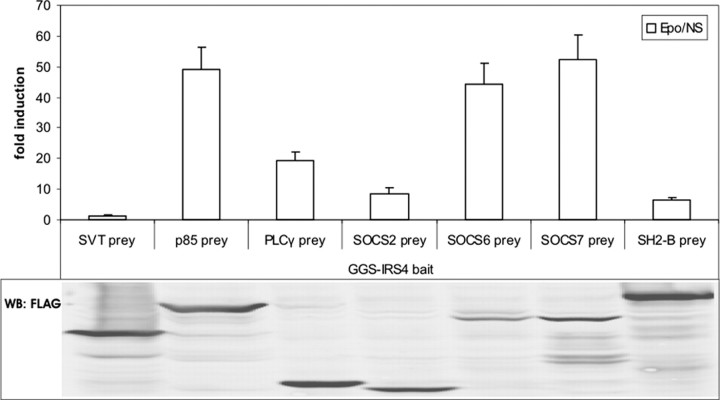

IRS4, like all IRS family members, acts as an adaptor protein in hormone and cytokine signaling (21). To determine interactions with IRS4, a GGS-IRS4 bait protein was transiently coexpressed in N38 cells with various prey proteins and the rPAP luciferase reporter construct (Fig. 5). The p85 subunit of the PI3K, SOCS6, and SOCS7 are known IRS4 binders (35, 38), and clear MAPPIT signals were obtained in each case. In addition, phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ) and SOCS2 preys also gave rise to elevated MAPPIT signals.

Fig. 5.

Interaction Partners of IRS4

GGS-MAPPIT. N38 cells were transiently cotransfected with plasmids encoding the chimeric GGS-IRS4 bait construct and different prey constructs as indicated, combined with the pXP2d2-rPAP1-luci reporter. The SVT and SH2-B preys were used to determine background signaling and functional bait expression, respectively. The transfected cells were either stimulated with erythropoietin (Epo) for 24 h or left untreated (NS, not stimulated). Luciferase measurements were performed in quadruplicate and are expressed as mean fold induction (Epo/NS) + sd. Expression of the FLAG-tagged prey proteins was verified on lysates using anti-FLAG antibody. Results are representative for six independent experiments.

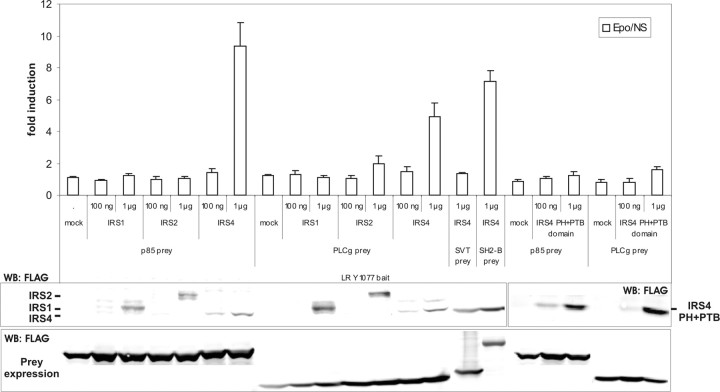

To further establish the adaptor role of IRS4 in leptin signaling, we coexpressed a gradient of FLAG-tagged IRS1, IRS2, or IRS4 proteins together with the GGS-LR Y1077 bait and the p85 or PLCγ prey. IRS1 and IRS2 were not able to link p85 or PLCγ to this mLR motif, in contrast to IRS4 (Fig. 6). When expressing only the PH+PTB domain of IRS4, its adaptor function is lost, indicating that p85 and PLCγ both interact with the C-terminal region of IRS4.

Fig. 6.

IRS4 Recruits the PI3K p85 Subunit and PLCγ to the mLR

GGS-MAPPIT. N38 cells were transiently cotransfected with plasmids encoding the chimeric GGS-LR Y1077 bait construct and the p85 or PLCγ prey construct, together with a mock vector or a gradient of an IRS1, IRS2, IRS4, or IRS4 PH+PTB domain expression vector, combined with the pXP2d2-rPAP1-luci reporter. The SVT and SH2-B preys were used to determine background signaling and functional bait expression, respectively. The transfected cells were either stimulated with erythropoietin (Epo) for 24 h or left untreated (NS, not stimulated). Luciferase measurements were performed in quadruplicate and are expressed as mean fold induction (Epo/NS) + sd. Expression of the FLAG-tagged prey and adaptor proteins was verified on lysates using anti-FLAG antibody. Results are representative for five independent experiments.

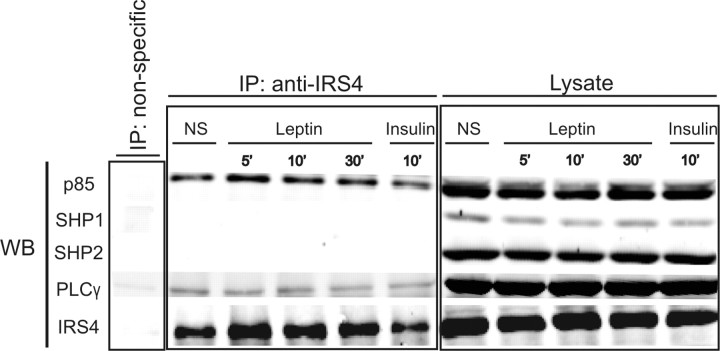

Next to the MAPPIT experiments, which are based on overexpression of a bait and prey protein, we performed co-IP experiments to confirm the relationship between IRS4 and downstream signaling proteins on an endogenous level. After stimulation with leptin (100 ng/ml) or insulin (100 nm), we immunoprecipitated IRS4 from lysates of HEK293 cells stably expressing the mLR. The immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for IRS4, p85, PLCγ, SHP1, and SHP2 (Fig. 7). Our results indicate that IRS4 can serve as a docking protein for p85 and PLCγ. We observed constitutive association of p85 and PLCγ with IRS4, as was described before for IRS4-p85 in lysates from untreated vs. insulin-treated cells (35). SHP1 and SHP2, known binders to IRS1 or IRS2, showed no association with IRS4 after leptin or insulin stimulation.

Fig. 7.

Interaction Partners of IRS4 in HEK293 Cells Stably Expressing the mLR

Lysates of nonstimulated (NS), leptin-treated (100 ng/ml), or insulin-treated (100 nm) HEK293 cells stably expressing the mLR were immunoprecipitated (IP) with a rabbit anti-IRS4 antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and assayed for the presence of p85, SHP1, SHP2, PLCγ, or IRS4 by Western blotting (WB) (left panel) as described in Materials and Methods. The first lane shows a mock precipitation using a normal rabbit IgG antibody as a nonspecific control. The right panel shows the expression of the proteins in the lysates before the IP. Each immunoprecipitate was derived from 1 mg cell protein lysate. Representative blots of three separate experiments are shown. WB, Western blot.

DISCUSSION

Leptin and insulin regulate energy expenditure and glucose homeostasis by acting on hypothalamic neurons, and cross-talk between the insulin and leptin signal transduction pathways is well documented. Both hormones can activate the IRS-PI3K pathway in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (25, 39), and neuron-specific insulin receptor knockout mice display obesity with leptin resistance (40). Furthermore, expression of LRs in the arcuate nucleus of genetically obese, LR-deficient Koletsky rats improved insulin sensitivity in a PI3K-dependent way (41). STAT3-independent signals triggered by the LR seem to be especially important in the control of orexigenic neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) expression, glucose homeostasis, linear growth, and fertility, and leptin requires intact hypothalamic PI3K signaling to inhibit NPY and AgRP expression (42, 43, 44). Although the relative contributions of insulin and leptin in functional hypothalamic signaling are difficult to assess, the importance of the PI3K pathway is clear.

IRS2-deficient mice show impaired leptin- and insulin-stimulated PI3K activity in the hypothalamus and are leptin resistant (45). Neuron-specific deletion of IRS2 causes an obese, hyperphagic phenotype in mice, establishing a crucial role for IRS2 in brain control of energy homeostasis, although IRS2 deletion from proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons has no apparent body weight phenotype (46). In contrast with IRS2 that has a widespread expression pattern in the brain, IRS4 expression is more restricted to the hypothalamus (28, 29). IRS4 mRNA can also be detected in mouse skeletal muscle, liver, heart, brain, and kidney (47). IRS4-deficient mice exhibit mild defects in reproduction, glucose homeostasis, and growth (30), suggesting that IRS4 may contribute to a STAT3-independent pathway in leptin signaling.

It was reported that serum leptin concentrations in IRS4 knockout male mice backcrossed onto a C57BL/6J background were higher than those of wild-type littermates. Because the IRS4 gene is located on the X chromosome, only two genotypes, IRS4+/Y and IRS4−/Y, are possible in male mice. After intercrossing IRS2 and IRS4 knockout mice, it was found that serum leptin levels of IRS2+/− IRS4−/Y were significantly higher than those of IRS2+/− IRS4+/Y littermates, almost comparable to those of IRS2 knockout (IRS2−/− IRS4+/Y) littermates. Intraperitoneal administration of leptin revealed that IRS2+/− IRS4−/Y mice were more resistant to leptin compared with IRS2+/− IRS4+/Y and wild-type mice (48). These results strongly suggested that, next to IRS2, IRS4 also might be implicated in hypothalamic leptin signaling, but no direct evidence for this was provided so far.

MAPPIT allows the study of protein-protein interactions in the physiologically highly relevant context of intact human cells. Because of the central role of the hypothalamus in LR signaling, MAPPIT experiments were carried out in the mouse hypothalamic N38 cell line (33). We used several MAPPIT variations to study the interaction of IRS4 with the murine LR long isoform (Fig. 1). IRS4 was shown to interact with the pY1077 motif, either within the full LR configuration or as an isolated motif (Fig. 2). MAPPIT experiments were based on expression of bait, adaptor, and prey proteins. To study the function of IRS4 at the endogenous level, a HEK293 cell line was generated that stably expresses the murine LR. HEK293 cells have the advantage that IRS4 levels are sufficiently high to be suited for co-IP experiments (35). Again, we demonstrated that IRS4 interacts in a leptin-dependent way with the mLR, supporting the phosphorylation dependency of this association that was observed in our MAPPIT analysis using the mutant F1077 motif and by phosphopeptide affinity chromatography. Y1077 of the LR lies in a highly conserved context (comparable to the Y985 and Y1138 motifs) and was shown to be phosphorylated after leptin stimulation (49). Recent reports support its role in LR signaling. pY1077 was shown to be involved in STAT5 activation in HEK293 and HIT-T15 insulinoma cells (49, 50) and was demonstrated to serve as an interaction site for cytokine-inducible-SH2-containing protein, SOCS2, and SOCS3 (12, 32).

IRS family members (IRS1–IRS6) all share a common structure: a PH domain at the N terminus, followed by a PTB domain and a C-terminal domain containing multiple potential phosphotyrosine docking sites (36). In general, the PH domain mediates recruitment of proteins to the plasma membrane by binding to phosphoinositides such as phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate or binding to membrane-associated proteins or a combination of both. The PTB domain recognizes peptide sequences containing variations on an NPXpY motif typically located in the juxtamembrane regions of integral plasma membrane proteins. Using IRS4 subdomains as prey in our MAPPIT experiments and also by co-IP, we found that the PH domain of IRS4 is sufficient for LR binding (Fig. 3). The PH domain of IRS1 is required, but not sufficient, for the coupling of IRS1 to the activated insulin receptor (51, 52, 53). The IRS1 PH and PTB domain may act cooperatively to localize IRS1 at the plasma membrane in association with the receptor (54). In contrast to IRS1 and IRS2, IRS3 and IRS4 are located at the plasma membrane in an insulin-independent manner (55, 56), suggesting a different role for the PH domain of IRS3 and IRS4 in plasma membrane targeting and subsequent (insulin) receptor interactions. For the LR-IRS4 interaction, two binding patterns seem possible. The PH domain might interact in a phosphorylation-dependent manner with the pY1077 of the LR. However, PH domains typically do not directly mediate phosphotyrosine-dependent interactions. Alternatively, PH domain-dependent IRS4 recruitment to the LR may be indirect, requiring a coupling protein that binds to the pY1077 motif. A possible membrane-associated interaction partner of IRS proteins is the PH domain interacting protein (PHIP), which interacts with the PH domain of IRS1 and may regulate its association to the insulin receptor (53). A recent study indicates that other, so far unknown proteins involved in PH domain recruitment exist (57). Additional studies are thus required to identify the physiological targets of the PH domain of IRS proteins.

It is well established that insulin stimulation leads to strong (4-fold) IRS4 tyrosine phosphorylation in HEK293 cells (37, 40). We observed a weaker (1.5-fold), but consistent IRS4 tyrosine phosphorylation upon leptin stimulation (Fig. 4). The precise identity of the tyrosine motifs that are phosphorylated by the insulin receptor or JAK2 kinases remains, however, unclear at present. Consequently, the extent of phosphorylation shown in Fig. 4 may be misleading because it is well known that an antibody-based readout may strongly vary between different phosphotyrosine motifs (32, 50). More extensive analysis, e.g. using mass-spectrometry-based approaches, will be required to solve this issue.

IRS4, like all members of the IRS family, serves as a multi-adaptor protein. It is known that IRS4 interacts with the regulatory p85 subunit of the PI3K, Grb2 (35, 56), members of the Crk family (58), protein phosphatase 4 (59), SOCS6, SOCS7 (38), Brk kinase (60), IRAS (61), SHP2, and PKC-ζ (56) in various cell types after stimulation with the appropriate stimulus. Using MAPPIT in N38 cells, we were able to find both known (p85, SOCS6, and SOCS7) and new (PLCγ and SOCS2) interaction partners of IRS4 (Fig. 5). SOCS2 and PLCγ were reported before as being recruited to the pY1077 motif of the LR in HEK293T and hematopoietic cells (32, 62). These interactions likely occur indirectly via IRS4, especially given the high levels of endogenous IRS4 in HEK293T cells (35). This adaptor function of IRS4 was further demonstrated by coexpressing IRS4 together with the LR Y1077 motif as bait and p85 or PLCγ as preys; only upon cotransfection of IRS4 were the p85 or PLCγ prey able to interact with the LR motif. When coexpressing only the PH and PTB of IRS4, its function is lost, indicating that p85 and PLCγ both interact with one or more phosphotyrosines in the C-terminal region of IRS4 (Fig. 6). In contrast to HEK293 cells, the endogenous levels of IRS4 in N38 cells were insufficient to support a detectable MAPPIT signal (data not shown). This association of IRS4 with the p85 subunit of the PI3K and PLCγ directly demonstrates that like the other members of the IRS family, IRS4 is a docking and effector protein for specific SH2 domain-containing proteins (Fig. 7).

IRS2 and IRS4 are both expressed in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (28), and because both can interact with the p85 subunit of PI3K, redundancy exists at the convergent PI3K pathway of central leptin and insulin signaling. However, because of the complex heterogeneity of neurons in the hypothalamus, IRS2 and IRS4 may be expressed in cells with a different neuropeptide phenotype. Also, sequence divergence in the C-terminal part of these IRS proteins suggests that differences in signaling capacity may exist. The detailed deciphering of the individual contributions of IRS2 and IRS4 in hypothalamic signaling will thus require sophisticated, cell-type-specific ablation studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs

Generation of the mutant murine LR (mLR-YYF) in the pMET7 expression vector was described elsewhere (63). Construction of the pCEL-60GGS-mLR Y985 and pCEL-60GGS-mLR Y1077 baits was done by transferring the fragment encoding the LR motif from the pSEL-60GGS vector (32) with SacI-NotI to the analogous pCEL-60GGS vector.

The Y to F mutants of the mLR motif baits were created through site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using the primer pair 5′-GAGACAACCCTCAGTTAAATTTGCAACTCTGGTCAGCAACG-3′ and 5′-CGTTGCTGACCAGAGTTGCAAATTTAACTGAGGGTTGTCTC-3′ for pCEL-60GGS-mLR F985 and primer pair 5′-GGGAGAAGTCTGTCTGTTTTCTAGGGGTCACCTCCGTCAAC-3′ and 5′-GTTGACGGAGGTGACCCCTAGAAAACAGACAGACTTCTCCC-3′ for pCEL-60GGS-mLR F1077.

The mLR motif containing both Y985 and Y1077 was amplified by PCR with forward primer 5′-GCCGAGCTCATGGAAAAATAAAGATGAG-3′ containing a SacI site and reverse primer 5′-CGGGCGGCCGCTCAAGGTACAAAGTTCTCACC-3′ containing a NotI site and a stop codon, allowing in-frame coupling to the pCEL-60GGS chimeric bait receptor. The 5′ part and 3′ part of IRS4 were amplified by PCR (see Table 1) on cDNA of mouse hypothalamic N38 cells (33) and were inserted in the SacI-NotI opened pCEL-60GGS vector through a three-point ligation.

Table 1.

Overview of the Primers for the IRS Constructs Used in this Study

| PCR Product | Target Vector | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Cloning Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRS4 (5′ part) | pCEL-60GGS | TGCGAGCTCAATGGCGAGTTGCTCCTTCTCTGGC | TCAGGCTGTGGGATCCTTCCCGGGCTAGGTGCTGAGCG | SacI-BamHI |

| IRS4 (3′part) | pCEL-60GGS pMG2 | GCCCGGGAAGGATCCCACAGCCTGAAGATGTCCCC | TGAGCGGCCGCTCACTTCCTGTAGTCTCGTCTGGC | BamHI-NotI |

| IRS4 (5′ part) | pMG2 | CGCGGAATTCATGGCGAGTTGCTCCTTCTCTGGC | TCAGGCTGTGGGATCCTTCCCGGGCTAGGTGCTGAGCG | EcoRI-BamHI |

| IRS4 PH domain | pMG2 | CGCGGAATTCATGGCGAGTTGCTCCTTCTCTGGC | CGATCTAGATTAGAGGCGGCTGAGGAGCAAGTACC | EcoRI-XbaI |

| IRS4 PTB domain | pMG2 | TCTGAATTCGATGTGTGGCAGGTAGTAGTG | CGATCTAGATTACAAGGCTCTCATCTTCTCCAGAAACAGC | EcoRI-XbaI |

| IRS4 PH+PTB domain | pMG2 | CGCGGAATTCATGGCGAGTTGCTCCTTCTCTGGC | CGATCTAGATTACAAGGCTCTCATCTTCTCCAGAAACAGC | EcoRI-XbaI |

| IRS4 pTyr domain | pMG2 | TCTGAATTCTGCGCAGATGAATACAGAGCCCGATGCCG | TGAGCGGCCGCTCACTTCCTGTAGTCTCGTCTGGC | EcoRI1-NotI |

| IRS4 PTB+pTyr domain | pMG2 | TCTGAATTCGATGTGTGGCAGGTAGTAGTG | TGAGCGGCCGCTCACTTCCTGTAGTCTCGTCTGGC | EcoRI1-NotI |

| IRS1 | pMG2 | GCGGAATTCATGGCGAGCCCTCCGGATACC | GCGGCGGCCGCCTATTGACGATCCTCTGG | EcoRI1-NotI |

| IRS2 | pMG2 | CGCGGTAACCATGGCTAGCGCGCCCCTGCC | GCGCTCGAGTCACTCTTTCACGACTGTGGC | BstEII-XhoI |

These PCR fragments were first cloned in a pZeroBlunt vector (Invitrogen) and then partially cut with EcoRI before ligation into the pMG2 vector.

The different IRS4 (subdomain) preys were amplified by PCR using pCEL-60GGS-IRS4 as a template (see Table 1) and inserted in the EcoRI/BstEII-XbaI/NotI opened pMG2 prey vector. The pMG2-SVT, pMG2-p85 FL, pMG2-PLCγ(2xSH2), pMG2-CIS, pMG2-SOCS2, pMG2-SOCS6, pMG2-SOCS7, and pMG2-SH2-B prey constructs and the pCEL-60GGS-FKBP12 constructs were described elsewhere (32, 64, 65, 66).

Murine IRS1 and IRS2 were amplified by PCR (see Table 1) on cDNA of N38 cells and pCT-mIRS2 (gift from Dr. M. Niessen), respectively. The pMET7 expression vectors expressing full-length IRS1, IRS2, or IRS4 were generated by cutting pMG2-IRS1 with SacI and partially with EcoRI, pMG2-IRS2 with EcoRI and partially with XbaI, and pMG2-IRS4 with XbaI and partially with EcoRI, respectively, allowing ligation of the IRS coding fragments in the EcoRI-SacI/XbaI cut pMET7 expression vector. The pMET7-IRS4 subdomain constructs were obtained by EcoRI-XbaI insert swaps from the parental pMG2-based vectors. For the pMET7-FKBP12 construct, FKBP12 was cut from the pMG2-FKBP12 construct described earlier (67) using EcoRI and NotI, and cloned in the pMET7 vector. Generation of pMET7-SOCS3 and a luciferase reporter construct containing the STAT3-responsive rat pancreatitis-associated protein I (rPAP1) promoter (pXP2d2-rPAP1-luci) was described previously (12).

The V5-tagged mLR expression construct was created by amplifying the 5′ part of the mLR with forward primer 5′-GCGGCGGCGGTCGACTAGGTAAGCCTATCCCTAACCCTCTCCTCGGTCTCGATTCTACGTGGAAAT T T AAGTTGTTTTG-3′ containing a SalI site and a V5 coding sequence and reverse primer 5′-CCTGGACACTGTCACCTGATG-3′ recognizing a unique DraIII site in the mLR sequence, allowing insertion in the XhoI-DraIII opened pMET7-mLR ΔCRH1, ΔIg, ΔCRH2 vector (68). All constructs were verified by DNA sequence analysis.

Cell Culture, Transfection Procedures, and Luciferase Reporter Assays

A pcDNA5/FRT vector expressing the long isoform of the mLR was stably integrated in HEK293-Flp-In cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as described previously (31). N38, HEK293-Flp-In, and HEK293T cells were cultured in an 8% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37 C and grown in DMEM (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal calf serum (Cambrex Corp., East Rutherford, NJ). For all MAPPIT experiments, 3.5 × 105 N38 cells were seeded in six-well plates and transfected overnight with approximately 3.5 μg plasmid DNA (standard: 1 μg bait plasmid, 1.5 μg prey plasmid, and 1 μg pXP2d2-rPAP1-luci) using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The next day, cells were washed with PBS, transferred to a 96-well plate, and left untreated or stimulated with 100 ng/ml mouse leptin or 5 ng/ml hEpo (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for at least 24 h. Luciferase activity from quadruplicate samples was measured by chemiluminescence in a TopCount luminometer (Canberra Packard, Meriden CT) and expressed as fold induction (stimulated/nonstimulated).

(Phospho)Peptide Affinity Chromatography

(Phospho)peptide affinity chromatography experiments were performed using the biotin-NHREKSVC(P)Y1077LGVTSVNR peptides and lysates from HEK293T cells transfected with either the pMET7-FLAG-FKBP12 or pMET7-FLAG-IRS4 expression constructs as described before (32).

Western Blot Analysis

N38, HEK293, and HEK293T cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in modified RIPA buffer [200 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.05% SDS, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm NaF, 20 mm β-glycerophosphate, and Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN)]. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 C. The 5× loading buffer [156 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 25% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue sodium salt, 5% β-mercaptoethanol] was added to the cell lysates, which were then resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Blotting efficiency was checked by Ponceau S staining (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). FLAG-tagged proteins were revealed using consecutively monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody M2 (Sigma) and antimouse-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Amersham Biosciences), diluted in Tris-buffered saline supplemented with 5% dried skimmed milk and 0.1% Tween 20, and visualized using the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Co-IP

Approximately 2.5 × 106 HEK293T cells were transfected with pMET7-V5-mLR and pMET7-FLAG-IRS4 (or IRS4 subdomain) expression vectors using the calcium phosphate transfection procedure and were stimulated with leptin (100 ng/ml) for 10 min. FLAG-tagged proteins in the cleared lysates (modified RIPA buffer) were immunoprecipitated using the FLAG immunoprecipitation kit (Sigma). After SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, interactions were detected using an anti-V5 antibody (Invitrogen) and antimouse-HRP as described above.

For the endogenous mLR-IRS4 co-IP experiment, HEK293 cells, stably expressing the mLR, were preincubated in serum-free medium for 4 h before stimulation with 100 ng/ml leptin. Cleared lysates were incubated with an in-house-made rat monoclonal antibody directed against the extracellular domain of the mLR (Van der Heyden, J., unpublished data) or normal rat IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and protein G-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences). After SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, blots were incubated with a polyclonal rabbit anti-IRS4 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and antirabbit-HRP as described above. Afterward, the blots were stripped using stripping buffer [2% SDS, 31 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 50 mm β-mercaptoethanol] and reprobed with a polyclonal goat anti-mLR antibody (K-20) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

For the detection of endogenous IRS4 phosphorylation or the interaction between endogenous IRS4 and p85, PLCγ, SHP1, or SHP2, HEK293 cells stably expressing the mLR were preincubated in serum-free medium for 4 h before stimulation with 100 ng/ml leptin or 100 nm insulin (Novo Nordisk, Copenhagen, Denmark). Cleared lysates (1 mg total protein) were incubated with a rabbit anti-IRS4 antibody or normal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) and resolved using SDS-PAGE. Quantitative Western blot analysis was performed using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. In brief, blots were blocked in Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-Cor). After incubation of the blots with both rabbit anti-IRS4 and a mouse monoclonal anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (pY100) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) diluted in Odyssey blocking buffer with 0.1% Tween 20, followed by incubation with both an IRDye 680 goat antirabbit and an IRDye 800 goat antimouse secondary antibody, quantitative Western blot analysis was performed using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor). For the detection of the interaction of IRS4 with p85, PLCγ, SHP1, or SHP2, blots were incubated with rabbit anti-p85 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), rabbit anti-PLCγ1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-SHP1, or mouse anti-SHP2 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), respectively, diluted in Odyssey blocking buffer with 0.1% Tween 20, followed by incubation with an IRDye 800 goat antirabbit or an IRDye 680 goat antimouse secondary antibody.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to Dr. M. Niessen for the pCT-mIRS2 vector.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from The Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders (FWO-V Grant No. 3G016406 to J.W.).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online December 28, 2007

Abbreviations: Co-IP, Coimmunoprecipitation; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; IRS, insulin receptor substrate; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; LR, leptin receptor; MAPPIT, mammalian protein-protein interaction trap; mLR, mouse LR; PH, pleckstrin homology; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PLCγ, phospholipase Cγ; PTB, phosphotyrosine-binding; SH2, src homology 2; SHP2, SH2-containing phosphatase 2; SOCS3, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription-3; SVT, SV40 large T protein.

References

- 1.Zhang YY, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM 1994. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homolog. Nature 372:425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman JM, Halaas JL 1998. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature 395:763–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tartaglia LA, Dembski M, Weng X, Deng NH, Culpepper J, Devos R, Richards GJ, Campfield LA, Clark FT, Deeds J, Muir C, Sanker S, Moriarty A, Moore KJ, Smutko JS, Mays GG, Woolf EA, Monroe CA, Tepper RI 1995. Identification and expression cloning of a leptin receptor, OB-R. Cell 83:1263–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halaas JL, Gajiwala KS, Maffei M, Cohen SL, Chait BT, Rabinowitz D, Lallone RL, Burley SK, Friedman JM 1995. Weight-reducing effects of the plasma protein encoded by the obese gene. Science 269:543–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelleymounter MA, Cullen MJ, Baker MB, Hecht R, Winters D, Boone T, Collins F 1995. Effects of the obese gene product on body weight regulation in ob/ob mice. Science 269:540–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H, Charlat O, Tartaglia LA, Woolf EA, Weng X, Ellis SJ, Lakey ND, Culpepper J, Moore KJ, Breitbart RE, Duyk GM, Tepper RI, Morgenstern JP 1996. Evidence that the diabetes gene encodes the leptin receptor: identification of a mutation in the leptin receptor gene in db/db mice. Cell 84:491–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumann H, Morella KK, White DW, Dembski M, Bailon PS, Kim HK, Lai CF, Tartaglia LA 1996. The full-length leptin receptor has signaling capabilities of interleukin 6-type cytokine receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:8374–8378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaisse C, Halaas JL, Horvath CM, Darnell JE, Stoffel M, Friedman JM 1996. Leptin activation of Stat3 in the hypothalamus of wildtype and ob/ob mice but not db/db mice. Nat Genet 14:95–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjorbaek C, Elmquist JK, Frantz JD, Shoelson SE, Flier JS 1998. Identification of SOCS-3 as a potential mediator of central leptin resistance. Mol Cell 1:619–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn SL, Bjornholm M, Bates SH, Chen ZB, Seifert M, Myers MG 2005. Feedback inhibition of leptin receptor/Jak2 signaling via Tyr(1138) of the leptin receptor and suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. Mol Endocrinol 19:925–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjorbaek C, Lavery HJ, Bates SH, Olson RK, Davis SM, Flier JS, Myers MG 2000. SOCS3 mediates feedback inhibition of the leptin receptor via Tyr985 J Biol Chem 275:40649–40657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eyckerman S, Broekaert D, Verhee A, Vandekerckhove J, Tavernier J 2000. Identification of the Y985 and Y1077 motifs as SOCS3 recruitment sites in the murine leptin receptor. FEBS Lett 486:33–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjorbaek C, Buchholz RM, Davis SM, Bates SH, Pierroz DD, Gu H, Neel BG, Myers MG, Flier JS 2001. Divergent roles of SHP-2 in ERK activation by leptin receptors. J Biol Chem 276:4747–4755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banks AS, Davis SM, Bates SH, Myers MG 2000. Activation of downstream signals by the long form of the leptin receptor. J Biol Chem 275:14563–14572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui H, Cai F, Belsham DD 2006. Leptin signaling in neurotensin neurons involves STAT, MAP kinases ERK1/2, and p38 through c-Fos and ATF1. FASEB J 20:2654–2656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen JH, Sakaida I, Uchida K, Terai S, Okita K 2005. Leptin enhances TNF-α production via p38 and JNK MAPK in LPS-stimulated Kupffer cells. Life Sci 77:1502–1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin HJ, Oh J, Kang SM, Lee JH, Shin MJ, Hwang KC, Jang Y, Chung JH 2005. Leptin induces hypertrophy via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 329:18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao AZ, Huan JN, Gupta S, Pal R, Sahu A 2002. A phosphatidylinositol 3kinase-phosphodiesterase 3B-cyclic AMP pathway in hypothalamic action of leptin on feeding. Nat Neurosci 5:727–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minokoshi Y, Alquier T, Furukawa N, Kim YB, Lee A, Xue BZ, Mu J, Foufelle F, Ferre P, Birnbaum MJ, Stuck BJ, Kahn BB 2004. AMP-kinase regulates food intake by responding to hormonal and nutrient signals in the hypothalamus. Nature 428:569–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White MF 2002. IRS proteins and the common path to diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283:E413–E422 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.White MF 1998. The IRS-signalling system: a network of docking proteins that mediate insulin action. Mol Cell Biochem 182:3–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai DS, Dhe-Paganon S, Melendez PA, Lee JS, Shoelson SE 2003. Two new substrates in insulin signaling, IRS5/DOK4 and IRS6/DOK5. J Biol Chem 278:25323–25330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan CJ, Li MH, Rui LY 2004. SH2-B promotes insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1)- and IRS2-mediated activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway in response to leptin. J Biol Chem 279:43684–43691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen B, Novick D, Rubinstein M 1996. Modulation of insulin activities by leptin. Science 274:1185–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niswender KD, Morton GJ, Stearns WH, Rhodes CJ, Myers MG, Schwartz MW 2001. Intracellular signalling. Key enzyme in leptin-induced anorexia. Nature 413:794–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Withers DJ, Gutierrez JS, Towery H, Burks DJ, Ren JM, Previs S, Zhang YT, Bernal D, Pons S, Shulman GI, Bonner-Weir S, White MF 1998. Disruption of IRS-2 causes type 2 diabetes in mice. Nature 391:900–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burks DJ, de Mora JF, Schubert M, Withers DJ, Myers MG, Towery HH, Altamuro SL, Flint CL, White MF 2000. IRS-2 pathways integrate female reproduction and energy homeostasis. Nature 407:377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Numan S, Russell DS 1999. Discrete expression of insulin receptor substrate-4 mRNA in adult rat brain. Mol Brain Res 72:97–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bischof JM, Wevrick R 2005. Genome-wide analysis of gene transcription in the hypothalamus. Physiol Genom 22:191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fantin VR, Wang Q, Lienhard GE, Keller SR 2000. Mice lacking insulin receptor substrate 4 exhibit mild defects in growth, reproduction, and glucose homeostasis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 278:E127–E133 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Eyckerman S, Verhee A, Van der Heyden J, Lemmens I, Van Ostade X, Vandekerckhove J, Tavernier J 2001. Design and application of a cytokine-receptor-based interaction trap. Nat Cell Biol 3:1114–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavens D, Montoye T, Piessevaux J, Zabeau L, Vandekerckhove J, Gevaert K, Becker W, Eyckerman S, Tavernier J 2006. A complex interaction pattern of CIS and SOCS2 with the leptin receptor. J Cell Sci 119:2214–2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belsham DD, Cai F, Cui H, Smukler SR, Salapatek AMF, Shkreta L 2004. Generation of a phenotypic array of hypothalamic neuronal cell models to study complex neuroendocrine disorders. Endocrinology 145:393–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaw G, Morse S, Ararat M, Graham FL 2002. Preferential transformation of human neuronal cells by human adenoviruses and the origin of HEK 293 cells. FASEB J 16:869–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fantin VR, Sparling JD, Slot JW, Keller SR, Lienhard GE, Lavan BE 1998. Characterization of insulin receptor substrate 4 in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. J Biol Chem 273:10726–10732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lavan BE, Fantin VR, Chang ET, Lane WS, Keller SR, Lienhard GE 1997. A novel 160-kDa phosphotyrosine protein in insulin-treated embryonic kidney cells is a new member of the insulin receptor substrate family. J Biol Chem 272:21403–21407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schreyer S, Ledwig D, Rakatzi I, Kloting I, Eckel J 2003. Insulin receptor substrate-4 is expressed in muscle tissue without acting as a substrate for the insulin receptor. Endocrinology 144:1211–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krebs DL, Uren RT, Metcalf D, Rakar S, Zhang J-G, Starr R, De Souza DP, Hanzinikolas K, Eyles J, Connolly LM, Simpson RJ, Nicola NA, Nicholson SE, Baca M, Hilton DJ, Alexander WS 2002. SOCS-6 binds to insulin receptor substrate 4, and mice lacking the SOCS-6 gene exhibit mild growth retardation. Mol Cell Biol 22:4567–4578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niswender KD, Morrison CD, Clegg DJ, Olson R, Baskin DG, Myers MG, Seeley RJ, Schwartz MW 2003. Insulin activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: a key mediator of insulin-induced anorexia. Diabetes 52:227–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruning JC, Gautam D, Burks DJ, Gillette J, Schubert M, Orban PC, Klein R, Krone W, Muller-Wieland D, Kahn CR 2000. Role of brain insulin receptor in control of body weight and reproduction. Science 289:2122–2125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morton GJ, Gelling RW, Niswender KD, Morrison CD, Rhodes CJ, Schwartz MW 2005. Leptin regulates insulin sensitivity via phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signaling in mediobasal hypothalamic neurons. Cell Metabolism 2:411–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim MS, Pak YK, Jang PG, Namkoong C, Choi YS, Won JC, Kim KS, Kim SW, Kim HS, Park JY, Kim YB, Lee KU 2006. Role of hypothalamic Foxo1 in the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis. Nat Neurosci 9:901–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison CD, Morton GJ, Niswender KD, Gelling RW, Schwartz MW 2005. Leptin inhibits hypothalamic Npy and Agrp gene expression via a mechanism that requires phosphatidylinositol 3-OH-kinase signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 289:E1051–E1057 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Bates SH, Stearns WH, Dundon TA, Schubert M, Tso AWK, Wang Y, Banks AS, Lavery HJ, Haq AK, Maratos-Flier E, Neel BG, Schwartz MW, Myers MG 2003. STAT3 signalling is required for leptin regulation of energy balance but not reproduction. Nature 421:856–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki R, Tobe K, Aoyama M, Inoue A, Sakamoto K, Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Yoshimatsu H, Matsuhisa M, Nagasaka S, Ogata H, Tokuyama K, Nagai R, Kadowaki T 2004. Both insulin signaling defects in the liver and obesity contribute to insulin resistance and cause diabetes in Irs2−/− Mice. J Biol Chem 279:25039–25049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choudhury AI, Heffron H, Smith MA, Al-Qassab H, Xu AW, Selman C, Simmgen M, Clements M, Claret M, MacColl G, Bedford DC, Hisadome K, Diakonov I, Moosajee V, Bell JD, Speakman JR, Batterham RL, Barsh GS, Ashford MLJ, Withers DJ 2005. The role of insulin receptor substrate 2 in hypothalamic and β-cell function. J Clin Invest 115:940–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fantin VR, Lavan BE, Wang Q, Jenkins NA, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Keller SR, Lienhard GE 1999. Cloning, tissue expression, and chromosomal location of the mouse insulin receptor substrate 4 gene. Endocrinology 140:1329–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suzuki R, Tobe K, Inoue A, Kowatari N, Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Lienhard G, Kadowaki T 2003. Coordinate regulation of leptin signaling pathway by Irs2 and Irs4. Diabetes 52:A311–A311

- 49.Gong Y, Ishida-Takahashi R, Villanueva EC, Fingar DC, Munzberg H, Myers Jr MG 2007. The long form of the leptin receptor regulates STAT5 and ribosomal protein S6 via alternate mechanisms. J Biol Chem 282:31019–31027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hekerman P, Zeidler J, Bamberg-Lemper S, Knobelspies H, Lavens D, Tavernier J, Joost HG, Becker W 2005. Pleiotropy of leptin receptor signalling is defined by distinct roles of the intracellular tyrosines. FEBS J 272:109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yenush L, Makati KJ, Smith-Hall J, Ishibashi O, Myers Jr MG, White MF 1996. The pleckstrin homology domain is the principle link between the insulin receptor and IRS-1. J Biol Chem 271:24300–24306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burks DJ, Pons S, Towery H, Smith-Hall J, Myers Jr MG, Yenush L, White MF 1997. Heterologous pleckstrin homology domains do not couple IRS-1 to the insulin receptor. J Biol Chem 272:27716–27721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farhang-Fallah J, Randhawa VK, Nimnual A, Klip A, Bar-Sagi D, Rozakis-Adcock M 2002. The pleckstrin homology (PH) domain-interacting protein couples the insulin receptor substrate 1 PH domain to insulin signaling pathways leading to mitogenesis and GLUT4 translocation. Mol Cell Biol 22:7325–7336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dhe-Paganon S, Ottinger EA, Nolte RT, Eck MJ, Shoelson SE 1999. Crystal structure of the pleckstrin homology-phosphotyrosine binding (PH-PTB) targeting region of insulin receptor substrate 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:8378–8383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Razzini G, Ingrosso A, Brancaccio A, Sciacchitano S, Esposito DL, Falasca M 2000. Different subcellular localization and phosphoinositides binding of insulin receptor substrate protein pleckstrin homology domains. Mol Endocrinol 14:823–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Escribano O, Fernandez-Moreno MD, Zueco JA, Menor C, Fueyo J, Ropero RM, Diaz-Laviada I, Roman ID, Guijarro LG 2003. Insulin receptor substrate-4 signaling in quiescent rat hepatocytes and in regenerating rat liver. Hepatology 37:1461–1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaburagi Y OH, Satoh S, Yamashita R, Hamada K, Ikari K, Yamamoto-Honda R, Terauchi Y, Yasuda K, Noda M 2007. Role of IRS and PHIP on insulin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation and distribution of IRS proteins. Cell Struct Funct 32:69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karas M, Koval AP, Zick Y, LeRoith D 2001. The insulin-like growth factor I receptor-induced interaction of insulin receptor substrate-4 and Crk-II. Endocrinology 142:1835–1840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mihindukulasuriya KA, Zhou G, Qin J, Tan TH 2004. Protein phosphatase 4 interacts with and down-regulates insulin receptor substrate 4 following tumor necrosis factor-α stimulation. J Biol Chem 279:46588–46594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qiu H, Zappacosta F, Su W, Annan RS, Miller WT 2005. Interaction between Brk kinase and insulin receptor substrate-4. Oncogene 24:5656–5664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sano H, Liu SCH, Lane WS, Piletz JE, Lienhard GE 2002. Insulin receptor substrate 4 associates with the protein IRAS. J Biol Chem 277:19439–19447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Montoye T, Piessevaux J, Lavens D, Wauman J, Catteeuw D, Vandekerckhove J, Lemmens I, Tavernier J 2006. Analysis of leptin signalling in hematopoietic cells using an adapted MAPPIT strategy. FEBS Lett 580:3301–3307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eyckerman S, Waelput W, Verhee A, Broekaert D, Vandekerckhove J, Tavernier J 1999. Analysis of Tyr to Phe and fa/fa leptin receptor mutations in the PC12 cell line. Eur Cytokine Network 10:549–556 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Montoye T, Lemmens I, Catteeuw D, Eyckerman S, Tavernier J 2005. A systematic scan of interactions with tyrosine motifs in the erythropoietin receptor using a mammalian 2-hybrid approach. Blood 105:4264–4271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Piessevaux J, Lavens D, Montoye T, Wauman J, Catteeuw D, Vandekerckhove J, Belsham D, Peelman F, Tavernier J 2006. Functional cross-modulation between SOCS proteins can stimulate cytokine signaling. J Biol Chem 281:32953–32966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Uyttendaele I, Lemmens I, Verhee A, De Smet A-S, Vandekerckhove J, Lavens D, Peelman F, Tavernier J 2007. MAPPIT analysis of STAT5, CIS, and SOCS2 interactions with the growth hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 21:2821–2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eyckerman S, Lemmens I, Catteeuw D, Verhee A, Vandekerckhove J, Lievens S, Tavernier J 2005. Reverse MAPPIT: screening for protein-protein interaction modifiers in mammalian cells. Nat Methods 2:427–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zabeau L, Defeau D, Iserentant H, Vandekerckhove J, Peelman F, Tavernier J 2005. Leptin receptor activation depends on critical cysteine residues in its fibronectin type III subdomains. J Biol Chem 280:22632–22640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]