Abstract

Exercise can improve cognitive function and the outcome of neurodegenerative diseases, like Alzheimer’s disease. This effect has been linked to the increased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). However, the underlying molecular mechanisms driving the elevation of this neurotrophin remain unknown. Recently, we have reported a PGC-1α-FNDC5/irisin pathway, which is activated by exercise in the hippocampus in mice and induces a neuroprotective gene program, including Bdnf. This review will focus on FNDC5 and its secreted form “irisin”, a newly discovered myokine, and their role in the nervous system and its therapeutic potential. In addition, we will briefly discuss the role of other exercise-induced myokines on positive brain effects.

Keywords: Exercise, brain, cognition, FNDC5, irisin, BDNF, hippocampus, physical activity

INTRODUCTION

Exercise, especially endurance exercise, is known to have beneficial effects on brain health and cognitive function [11, 32, 53]. This improvement in cognitive function with exercise has been most prominently observed in the aging population [10]. Exercise has also been reported to ameliorate outcomes in neurological diseases like depression, epilepsy, stroke, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease [2, 4, 6, 44, 56]. The effects of exercise on the brain are most apparent in the hippocampus and its dentate gyrus, a part of the brain involved in learning and memory. Specific beneficial effects of exercise in the brain have been reported to include increases in the size of and blood flow to the hippocampus in humans and morphological changes in dendrites and dendritic spines, increased synapse plasticity and, importantly, de novo neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus in various mouse models of exercise [11, 32]. De novo neurogenesis in the adult brain occurs is observed in only two areas; the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus is one of them and exercise is one of the few known stimuli of this de novo neurogenesis [26].

One important molecular mediator for these beneficial responses in the brain to exercise is the induction of neurotrophins/growth factors, most notably brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). In animal models, BDNF is induced in various regions of the brain with exercise, most robustly in the hippocampus [44]. BDNF promotes many aspects of brain development including neuronal cell survival, differentiation, migration, dendritic arborization, synaptogenesis and plasticity [19, 37]. In addition, BDNF is essential for synaptic plasticity, hippocampal function and learning [28]. Highlighting the relevance of BDNF in human, individuals carrying the Val66Met mutation in the BDNF gene, exhibit decreased secretion of BDNF, display a decreased volume of specific brain regions, deficits in episodic memory function as well as increased anxiety and depression [14, 20]. Blocking BDNF signaling with anti-TrkB antibodies attenuates the exercise-induced improvement of acquisition and retention in a spatial learning task, as well as the exercise-induced expression of synaptic proteins [51, 52]. However, the underlying mechanism, by which BDNF is induced in exercise remains to be incompletely understood.

We recently described a role for the newly discovered “exercise-hormone” FNDC5 [5] and its secreted form “irisin” in the protective effects of exercise on the brain. Fndc5 expression is induced by exercise in the hippocampus in mice, which in turn, can activate BDNF and other neuroprotective genes [54]. Importantly, peripheral delivery of FNDC5 to the liver via adenoviral vectors, resulting in elevated blood irisin, induced expression of Bdnf and other neuroprotective genes in the hippocampus. These data indicate that either irisin itself can cross the blood-brain-barrier to induce these gene expression changes or irisin induces a factor x that can. This has significant implication for irisin as a novel therapeutic target. This review will examine previous literature about FNDC5/irisin as well as its therapeutic potential for treating neurodegenerative disease.

DISCOVERY OF FNDC5/IRISIN

In 2002, two groups independently cloned a novel gene that they termed either PeP or alternatively, Frcp2, and that contained a fibronectin type III (FNIII) domain, now named FNDC5 [16, 49]. Recently, our group identified FNDC5, as a PGC-1α-dependent myokine, that is secreted from muscle during exercise and induces some of the major metabolic benefits of exercise [5].

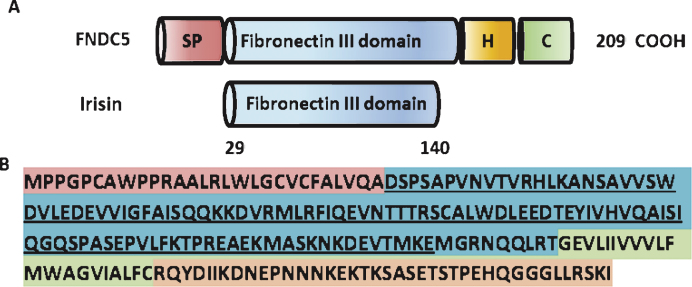

FNDC5 is a glycosylated type I membrane protein. It contains a N-terminal signal peptide (amino acid (aa) 1–28), a FNIII domain (aa 33–124), a transmembrane domain (aa 150–170), and a cytoplasmic tail (aa 171–209) (www.uniporot.org) (Schematic Fig. 1). The secreted form of FNDC5 contains 112 amino acids (aa 29–140), named irisin. It is generated by proteolytic cleavage and released into the circulation. The protease/sheddase responsible for that cleavage has not been identified, yet. Irisin is 100% conserved from mouse to human and is highly conserved across mammals. Irisin has been crystallized and its structure has been solved [45]. Interestingly, the FNIII-like domain shows an unusual confirmation with continuous intersubunit beta-sheet dimer, which has not been previously described for any other FNIII protein. Subsequent biochemical experiments confirmed the existence of irisin (bacterial recombinant) as a homodimer.

Fig.1.

Structure of the murine FNDC% and irisin protein. (A) Scheme of the murine FNDC5 protein structure (top) and murine irisin protein structure (bottom). SP = signal peptide, H = hydrophobic domain, C = cytoplasmic domain. (B) Murine FNDC5 amino acid sequence with corresponding domains colored. The irisin sequence is underlined.

TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATION OF FNDC5 EXPRESSION

The FNDC5 gene is located on human chromosome 1 and mouse chromosome 4, respectively. In silico analysis by Seifi et al. suggests that the putative core promoter of the mouse Fndc5 gene ranges from – 551 to +101 with respect to the transcriptional start sites and that it contains exon I and intron I of Fndc5 gene. This murine Fndc5 core promoter lacks a TATA box and is GC rich [46].

Fndc5 has been shown to be regulated by the transcriptional co-activator PGC-1α in skeletal muscle and neurons in vivo and in vitro [5, 54]. This could explain the enrichment of Fndc5 expression in highlyoxidative tissues, such as skeletal muscle, heart and brain, and its induction by endurance exercise, both states, in which PGC-1α expression is increased. Since PGC-1α is a transcriptional co-activator and therefore needs by definition a transcription factor to exert its biological function. In neurons its regulatory partner has been suggested to be ERRα, based on bioinformatical analysis of the murine Fndc5 promoter, which contains ERRα transcription factor binding sites, and biochemical experiments using an inverse pharmacological agonist and RNAi-mediated knock-down [54]. One report identifies SMAD3 as negative regulator of serum Irisin and skeletal muscle FNDC5 and PGC-1α during exercise [50].

IRISIN IN HUMANS

Irisin is a highly conserved polypeptide across mammals. In fact, it is 100% percent identical in mice and humans [5]. Such a high degree of conservation is often the result of evolutionary pressure to conserve function. Interestingly, the human FNDC5 has an atypical start of translation, ATA in place of ATG, compared to mouse Fndc5. While it is now known that a few percent of eukaryotic mRNAs begin translation with non-ATG start codons [23, 24, 38] and are often associated with regulation on the translational level [7, 48] recent reports [3, 42] have argued that this ATA codon in human FNDC5 was a “null mutation” or a “myth” and therefore human irisin would not be produced. Furthermore, the many reports of other groups measuring irisin in human by Western blot or ELISA have been suggest to be artifacts of poor antibody specificity [3, 15, 42] even though an earlier study had detected irisin circulating in human plasma using mass spectrometry- an unbiased method independent of the quality of existing antibodies [30]. (To identify and quantify irisin in human plasma, we used targeted mass spectrometry with control peptides enriched with stable isotopes as internal standards. This precise state-of-the-art method demonstrated that human irisin is mainly translated from its non-canonical ATA start codon [25]. In addition, it shows that in sedentary individuals irisin circulates at ∼3.6 ng/ml and that it was significantly increased in individuals undergoing aerobic interval training. This study determines at the atomical level that human irisin exits, circulates, and is regulated by certain forms of aerobic exercise.

FNDC5/IRISIN IN EXERCISE

FNDC5/irisin were first described as an exercise-induced myokine by Bostrom et al. in 2012 [5], who observed upregulation of Fndc5 gene expression in skeletal muscle and increases in serum irisin levels after prolonged endurance exercise in mice and humans. Increasing the circulating levels of irisin by overexpressing FNDC5 from adenoviral vectors in the liver, led to increased of “browning” of the white inguinal adipose tissue, i.e. the upregulation of mitochondrial gene expression, especially of Ucp1, and to increased glucose tolerance in mice – two of the major metabolic benefits of endurance exercise. By now, there are have been around 50 papers published that investigate FNDC5 and/or irisin in exercise in rodent studies and clinical trials in humans. Induction of Fndc5 mRNA in skeletal by endurance exercise has been confirmed in several studies in mice [41, 50, 54] and humans [3, 29, 34] using QPCR or RNA sequencing. As with all clinical studies, there are a lot of variables to consider, such as retrospective studies vs. intervention trials, age and fitness level of the subjects and, most importantly, the type of exercise protocol used and time point of sampling. However, there is a consensus building that studies that reported positive associations between irisin plasma level and exercise, performed early sampling and high intensity training protocols levels [12, 22, 27, 34]. The brief rise in circulating irisin levels after exercise is suggestive of an acute shedding event of irisin during exercise. There is little or no evidence so far that FNDC5 or irisin is upregulated by resistance exercise in mice or human; which is not unexpected since endurance exercise activates PGC-1α1, which has been shown to be the upstream regulator of Fndc5 gene expression, whereas resistance exercise activates a different isoform of PGC-1α, PGC-1α4 [43].

FNDC5/IRISIN IN METABOLISM

Initially, irisin was described as acting preferentially on the subcutaneous ‘beige’ fat and to cause ‘browning’ by increasing the expression of UCP-1 and other thermogenic genes [5, 55]. The result is increased thermogenesis and energy expenditure, with improved whole body glucose metabolism in obese mice [5]. A recent study in myostatin mutant mice suggests that the leaner body composition and reduced fat mass in those mice maybe caused by browning of the white adipose driven by higher levels of irisin (Fndc5) secreted from the skeletal muscle [47]. Many studies have described the relationship of FNDC5/irisin and various metabolic parameters, such as BMI, obesity, type 2 diabetes, age, or pregnancy etc. Recent reviews from Chen J.Q. et al. and Chen N. et al. nicely summarize the results of those studies [8, 9].

FNDC5/IRISIN IN NEURONAL DEVELOPMENT

Fndc5 is highly expressed in the brain, including the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum [13, 16, 49]. Irisin, the shed form of FNDC5 was identified in human cerebrospinal fluid by WB [40]. In addition, immunoreactivity against the extracellular domain of FNDC5/irisin was detected in human hypothalamic sections, especially paraventricular neurons [40]. Other tissues with high FNDC5 levels include skeletal muscle and the heart. Fndc5 gene expression increases during differentiation of rat pheochromocytoma-derived PC12 cells into neuron-like cells [35]. FNDC5 levels are enhanced after differentiation of human embryonic stem cell-derived neural cells into neurons [18] as well as during the maturation of primary cortical neurons in culture and during brain development in vivo [54].

Knockdown of FNDC5 in neuronal precursors impaired their development into mature neurons (and astrocyte), suggesting a developmental role of FNDC5 in neurons [21]. On the other hand, forced expression of FNDC5 during neuronal precursor formation from mouse embryonic stem cells increased mature neuronal markers (Map2, b-tubulinIII and Neurocan) and astrocyte marker (GFAP) and BDNF. However, overexpression of FNDC5 in undifferentiated mouse embryonic stem cells did not have these effects, indicating that FNDC5 supports neural differentiation rather than lineage commitment [17]. Pharmacological doses of recombinant irisin increased cell proliferation in the mouse H19-7 hippocampal cell line [33]. Furthermore, forced expression of FNDC5 in primary cortical neurons increased cell survival in culture, whereas knockdown of FNDC5 had the opposite effect [54].

FNDC5/IRISIN – OTHER EFFECTS IN THE CNS

The group of Dr. Mulholland had taken in interest in the central nervous effects of irisin. In a first study, they injected irisin either into 3rd ventricle of rats or intravenously and measured the effects on blood pressure and cardiac contractibility [57]. Central administration of irisin activated neurons in the paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus as indicated by increased c-fos immunoreactivity. Central irisin administration also increased blood pressure and cardiac contractibility. In contrast, i.v. injection of irisin reduced blood pressure in both, control and spontaneously hypertensive rats. In a second study, Zhang et al. showed that central treatment of rats with irisin-Fc led to an increase in physical activity compared to control animals receiving IgG Fc peptide [58]. In addition, the centrally applied irisin also induced significant increases in oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production and heat production, indicating an increase in metabolic activity- possibly through SNS activation.

EXERCISE INDUCES HIPPOCAMPAL BDNF THROUGH A PGC-1α/FNDC5 PATHWAY

In a recent study, we have shown that FNDC5 is also elevated in the hippocampus of mice undergoing an endurance exercise regimen of 30-days free-wheel running. Neuronal Fndc5 gene expression is regulated by PGC-1α and Pgc1a -/- mice show reduced Fndc5 expression in the brain. Forced expression of FNDC5 in primary cortical neurons increases Bdnf expression, whereas RNAi-mediated knockdown of FNDC5 reduces Bdnf. Importantly, peripheral delivery of FNDC5 to the liver via adenoviral vectors, resulting in elevated blood irisin, induces expression of Bdnf and other neuroprotective genes in the hippocampus. Interestingly, a recent study investigating the effects of the flavonoid querceptin and hypobaric hypoxia, reported that quercetin administration to hyperbraric hypoxic rats increased expression of PGC-1α, FNDC5, and BDNF in the hippocampus [31].

Taken together, our findings link endurance exercise and the important metabolic mediators, PGC-1α and FNDC5, with BDNF expression in the brain. While more research will be required to determine whether the FNDC5/irisin protein actually improves cognitive function in animals, this study suggest that a natural substance given in the bloodstream might mimic some of the effects of endurance exercise on the brain.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR FNDC5/IRISIN IN EXERCISE AND THE BRAIN

However, this first study opens up importantquestions that need to be addressed in the future.

-

1)

Can irisin itself cross the blood brain barrier? Molecules can cross the blood brain barrier either through free discussion if the molecular weight is <400 Da and it forms <8 hydrogen bonds. However, recent studies suggest that other molecules can use either carrier- or receptor-mediated transport (RMT) through the blood brain barrier; a concept that is currently being explored by the pharmaceutical industry for drug delivery [36].

-

2)

Does a prolonged elevation of peripheral irisin confer neuroprotective effects and can this be achieved by peripheral administration of recombinant protein? So far there have been only two studies that injected recombinant irisin either into 3rd ventricle of rats or intravenously and monitored acute effects on blood pressure or activity within minutes [57, 58]. But no chronic long-term studies using a genetic model or repeated injections have been reported. Longer term administration of irisin will also allow to evaluate the effects on synaptic plasticity and cognition.

-

3)

FNDC5 is expressed in at highest levels in oxidative muscle, like skeletal muscle and heart, as well as the nervous tissue. Endurance exercise induces FNDC5 in skeletal muscle as well as in the hippocampus in mice [54]. Which tissue contributes to what extend to the beneficial effects of exercise on the brain? Tissue-specific deletion of Fndc5 in the skeletal muscle and the hippocampus will help to delineate the effects of skeletal muscle- vs. hippocampal-induced Fndc5 on central BDNF expression as well as on improvement of learning and memory by endurance exercise.

-

4)

What is the identity of the irisin receptor and intracellular signaling pathways used by irisin? Finding the irisin receptor will help to identify all possible target tissues of irisin effects and therefore targeted drug development.

OTHER CIRCULATING FACTORS FROM THE MUSCLE

While FNDC5/irisin is a very interesting molecule with therapeutic promise, this is not to say that we think that FNDC5/irisin captures all the benefits of exercise on the brain or that is the only important secreted molecule from muscle in exercise. In fact, other such molecules have been described, including BDNF, IGF-1, and VEGF, kyrurenic acid, and a variety of cytokines and chemokines, to name a few [1, 39, 53]. We expect that in the future additional molecules will be discovered and that some of those will fulfill their therapeutic potential.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C.D.W. was supported by a K99/R00-NIH Pathway to Independence (PI) Award (NS087096). Part of this work is funded by the JPB Foundation and NIH grants (DK31405 and DK90861) to Bruce M. Spiegelman. I thank Dr. Bruce Spiegelman for critical scientific discussions. I also thank Dr. Mark Jedrychowski for support with the art work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agudelo LZ, Femenia T, Orhan F, Porsmyr-Palmertz M, Goiny M, Martinez-Redondo V, Correia JC, Izadi M, Bhat M, Schuppe-Koistinen I, et al. Skeletal muscle PGC-1alpha1 modulates kynurenine metabolism and mediates resilience to stress-induced depression. Cell. 2014;159:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahlskog JE. Does vigorous exercise have a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson disease? Neurology. 2011;77:288–294. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225ab66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albrecht E, Norheim F, Thiede B, Holen T, Ohashi T, Schering L, Lee S, Brenmoehl J, Thomas S, Drevon CA, et al. Irisin – a myth rather than an exercise-inducible myokine. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:8889. doi: 10.1038/srep08889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arida RM, Cavalheiro EA, da Silva AC, Scorza FA. Physical activity and epilepsy: Proven and predicted benefits. Sports Medicine (Auckland, NZ) 2008;3:607–615. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boström P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, Korde A, Ye L, Lo JC, Rasbach KA, Boström EA, Choi JH, Long JZ, Kajimura S, Zingaretti MC, Vind BF, Tu H, Cinti S, Højlund K, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481(7382):463–468. doi: 10.1038/nature10777. Jan 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Yu L, Shah RC, Wilson RS, Bennett DA. Total daily physical activity and the risk of ADand cognitive decline in older adults. Neurology. 2012;78:1323–1329. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang KJ, Wang CC. Translation initiation from a naturally occurring non-AUG codon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:13778–13785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JQ, Huang YY, Gusdon AM, Qu S. Irisin: A new molecular marker and target in metabolic disorder. Lipids in Health and Disease. 2015;14:2. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-14-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen N, Li Q, Liu J, Jia S. Irisin, an exercise-induced myokine as a metabolic regulator: an updated narrative review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2015. May 7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Colcombe S, Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: A meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:125–130. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cotman CW, Berchtold NC, Christie LA. Exercise builds brain health: Key roles of growth factor cascades and inflammation. Trends Neuro Sci. 2007;30:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daskalopoulou SS, Cooke AB, Gomez YH, Mutter AF, Filippaios A, Mesfum ET, Mantzoros CS. Plasma irisin levels progressively increase in response to increasing exercise workloads in young, healthy, active subjects. European Journal of Endocrinology /European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2014;17:343–352. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dun SL, Lyu RM, Chen YH, Chang JK, Luo JJ, Dun NJ. Irisin-immunoreactivity in neural and non-neural cells of therodent. Neuroscience. 2013;240:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.02.050. Jun 14; Epub 2013 Mar 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, Bertolino A, Zaitsev E, Gold B, Goldman D, Dean M, et al. The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell. 2003;112:257–269. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erickson HP. Irisin and FNDC5 in retrospect: An exercise hormone or a transmembrane receptor? Adipocyte. 2013;2:289–293. doi: 10.4161/adip.26082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrer-Martinez A, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR. Mouse PeP: A novel peroxisomal protein linked to myoblast differentiation and development. Dev Dyn. 2002;224:154–167. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forouzanfar M, Rabiee F, Ghaedi K, Beheshti S, Tanhaei S, Shoaraye Nejati A, Jodeiri Farshbaf M, Baharvand H, Nasr-Esfahani MH. Fndc5 overexpression facilitated neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Biology International. 2015;39:629–637. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghahrizjani FA, Ghaedi K, Salamian A, Tanhaei S, Nejati AS, Salehi H, Nabiuni M, Baharvand H, Nasr-Esfahani MH. Enhanced expression of FNDC5 in human embryonic stem cell-derived neural cells along with relevant embryonic neural tissues. Gene. 2015;557:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenberg ME, Xu B, Lu B, Hempstead BL. New insights in the biology of BDNF synthesis and release: Implications in CNS function. The Journal of neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:12764–12767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3566-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hariri AR, Goldberg TE, Mattay VS, Kolachana BS, Callicott JH, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism affects human memory-related hippocampal activity and predicts memory performance. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23:6690–6694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06690.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashemi MS, Ghaedi K, Salamian A, Karbalaie K, Emadi-Baygi M, Tanhaei S, Nasr-Esfahani MH, Baharvand H. Fndc5 knockdown significantly decreased neural differentiation rate of mouse embryonic stem cells. Neuroscience. 2013;231:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huh JY, Mougios V, Kabasakalis A, Fatouros I, Siopi A, Douroudos II, Filippaios A, Panagiotou G, Park KH, Mantzoros CS. Exercise-Induced Irisin Secretion Is Independent of Age or Fitness Level and Increased Irisin May Directly Modulate Muscle Metabolism Through AMPK Activation. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;99:E2154–E2161. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell. 2011;147:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ivanov IP, Firth AE, Michel AM, Atkins JF, Baranov PV. Identification of evolutionarily conserved non-AUG-initiated N-terminal extensions in human coding sequences. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:4220–4234. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jedrychowski MP, Wrann CD, Paulo JA, Gerber KK, Szpyt J, Robinson MM, Nair KS, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM. Detection and quantitation of circulating human irisin by tandem mass spectrometry. Cell Metab. 2015. Aug 12; pii: S1550-4131(15)00392-7. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 26278051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Kobilo T, Liu QR, Gandhi K, Mughal M, Shaham Y, van Praag H. Running is the neurogenic and neurotrophic stimulus in environmental enrichment. Learn Mem. 2011;18:605–609. doi: 10.1101/lm.2283011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraemer RR, Shockett P, Webb ND, Shah U, Castracane VD. A transient elevated irisin blood concentration in response to prolonged, moderate aerobic exercise in young men and women. Hormone and metabolic research=Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung=Hormones et metabolisme. 2014;46:150–154. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1355381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuipers SD, Bramham CR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor mechanisms and function in adult synaptic plasticity: New insights and implications for therapy. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2006;9:580–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lecker SH, Zavin A, Cao P, Arena R, Allsup K, Daniels KM, Joseph J, Schulze PC, Forman DE. Expression of the irisin precursor FNDC5 in skeletal muscle correlates with aerobic exercise performance in patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:812–818. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.969543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee P, Linderman JD, Smith S, Brychta RJ, Wang J, Idelson C, Perron RM, Werner CD, Phan GQ, Kammula US, et al. Irisin and FGF21 are cold-induced endocrine activators of brown fat function in humans. Cell Metabolism. 2014;19:302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu P, Zou D, Yi L, Chen M, Gao Y, Zhou R, Zhang Q, Zhou Y, Zhu J, Chen K, et al. Quercetin ameliorates hypobaric hypoxia-induced memory impairment through mitochondrial and neuron function adaptation via the PGC-1alpha pathway. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. 2015;33:143–157. doi: 10.3233/RNN-140446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattson MP. Energy intake and exercise as determinants of brain health and vulnerability to injury and disease. Cell Metabolism. 2012;16:706–722. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moon HS, Dincer F, Mantzoros CS. Pharmacological concentrations of irisin increase cell proliferation without influencing markers of neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis in mouse H19-7 hippocampal cell lines. Metabolism. Clinical and Experimental. 2013;62:1131–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norheim F, Langleite TM, Hjorth M, Holen T, Kielland A, Stadheim HK, Gulseth HL, Birkeland KI, Jensen J, Drevon CA. The effects of acute and chronic exercise on PGC-1alpha, irisin and browning of subcutaneous adipose tissue in humans. The FEBS Journal. 2014;281:739–749. doi: 10.1111/febs.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostadsharif M, Ghaedi K, Hossein Nasr-Esfahani M, Mojbafan M, Tanhaie S, Karbalaie K, Baharvand H. The expression of peroxisomal protein transcripts increased by retinoic acid during neural differentiation. Differentiation. 2011;81:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardridge WM. Drug transport across the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1959–1972. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park H, Poo MM. Neurotrophin regulation of neural circuit development and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:7–23. doi: 10.1038/nrn3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peabody DS. Translation initiation at non-AUG triplets in mammalian cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:5031–5035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phillips C, Baktir MA, Srivatsan M, Salehi A. Neuroprotective effects of physical activity on the brain: A closer look at trophic factor signaling. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2014;8:170. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piya MK, Harte AL, Sivakumar K, Tripathi G, Voyias PD, James S, Sabico S, Al-Daghri NM, Saravanan P, Barber TM, et al. The identification of irisin in human cerebrospinal fluid: Influence of adiposity, metabolic markers, and gestational diabetes. American Journal of Physiology Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;306:E512–E518. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00308.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quinn LS, Anderson BG, Conner JD, Wolden-Hanson T. Circulating irisin levels and muscle FNDC5 mRNA expression are independent of IL-15 levels in mice. Endocrine. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Raschke S, Elsen M, Gassenhuber H, Sommerfeld M, Schwahn U, Brockmann B, Jung R, Wisloff U, Tjonna AE, Raastad T, et al. Evidence against a beneficial effect of irisin in humans. PloS One. 2013;8:e73680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruas JL, White JP, Rao RR, Kleiner S, Brannan KT, Harrison BC, Greene NP, Wu J, Estall JL, Irving BA, et al. A PGC-1alpha isoform induced by resistance training regulates skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell. 2012;151:1319–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Russo-Neustadt A, Beard RC, Cotman CW. Exercise, antidepressant medications, and enhanced brain derived neurotrophic factor expression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:679–682. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schumacher MA, Chinnam N, Ohashi T, Shah RS, Erickson HP. The structure of irisin reveals a novel intersubunit beta-sheet fibronectin type III (FNIII) dimer: Implications for receptor activation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:33738–33744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.516641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seifi T, Ghaedi K, Tanhaei S, Karamali F, Kiani-Esfahani A, Peymani M, Baharvand H, Nasr-Esfahani MH. Identification, cloning, and functional analysis of the TATA-less mouse FNDC5 promoter during neural differentiation. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 2014;34:715–725. doi: 10.1007/s10571-014-0053-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shan T, Liang X, Bi P, Kuang S. Myostatin knockout drives browning of white adipose tissue through activating the AMPK-PGC1α-Fndc5 pathway in muscle. FASEB J. 2013;27(5):1981–1989. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-225755. May; Epub 2013 Jan 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Starck SR, Jiang V, Pavon-Eternod M, Prasad S, McCarthy B, Pan T, Shastri N. Leucine-tRNA initiates at CUG start codons for protein synthesis and presentation by MHC class I. Science (New York, NY) 2012;336:1719–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1220270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teufel A, Malik N, Mukhopadhyay M, Westphal H. Frcp1 and Frcp2, two novel fibronectin type III repeat containing genes. Gene. 2002;297:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tiano JP, Springer DA, Rane SG. SMAD3 negatively regulates serum irisin and skeletal muscle FNDC5 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1alpha) during exercise. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2015;290:7671–7684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.617399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaynman S, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. Hippocampal BDNF mediates the efficacy of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:2580–2590. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vaynman SS, Ying Z, Yin D, Gomez-Pinilla F. Exercise differentially regulates synaptic proteins associated to the function of BDNF. Brain Res. 1070. pp. 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Voss MW, Vivar C, Kramer AF, van Praag H. Bridging animal and human models of exercise-induced brain plasticity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2013;17:525–544. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wrann CD, White JP, Salogiannnis J, Laznik-Bogoslavski D, Wu J, Ma D, Lin JD, Greenberg ME, Spiegelman BM. Exercise induces hippocampal BDNF through a PGC-1alpha/FNDC5 pathway. Cell Metabolism. 2013;18:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu J, Bostrom P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang AH, Khandekar M, Virtanen KA, Nuutila P, Schaart G, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Q, Wu Y, Zhang P, Sha H, Jia J, Hu Y, Zhu J. Exercise induces mitochondrial biogenesis after brain ischemia in rats. Neuroscience. 2012;205:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang W, Chang L, Zhang C, Zhang R, Li Z, Chai B, Li J, Chen E, Mulholland M. Central and Peripheral Irisin Differentially Regulate Blood Pressure. Cardiovascular drugs and therapy/sponsored by the International Society of Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Zhang W, Chang L, Zhang C, Zhang R, Li Z, Chai B, Li J, Chen E, Mulholland M. Irisin: A myokine with locomotor activity. Neuroscience Letters. 2015;595:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]