Abstract

In humans, deleterious mutations in the sterile α motif domain protein 9 (SAMD9) gene are associated with cancer, inflammation, weakening of the immune response, and developmental arrest. However, the biological function of SAMD9 and its sequence-structure relationships remain to be characterized. Previously, we found that an essential host range factor, M062 protein from myxoma virus (MYXV), antagonizes the function of human SAMD9. In this study, we examine the interaction between M062 and human SAMD9 to identify regions that are critical to SAMD9 function. We also characterize the in vitro kinetics of the interaction. In an infection assay, exogenous expression of SAMD9 N-terminus leads to a potent inhibition of wild-type MYXV infection. We reason that this effect is due to the sequestration of viral M062 by the exogenously expressed N-terminal SAMD9 region. Our studies reveal the first molecular insight into viral M062-dependent mechanisms that suppress human SAMD9-associated antiviral function.

Keywords: SAMD9, MYXV, host range factor, C7L superfamily, protein-protein interaction, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), immunoprecipitation, polymerization

Introduction

Sterile α motif domain protein 9 (SAMD9) is a cytoplasmic protein with diverse functions including antiviral, antineoplastic, and stress-responsive properties. Human SAMD9, and potentially the pathway that it governs, can be targeted by poxviruses as a general strategy for host evasion. In some poxviruses, proteomic studies have observed protein–protein interactions between SAMD9 and a C7L homolog (shown by immunoprecipitation) that has been correlated to the host range function (Liu and McFadden, 2015; Liu et al., 2011; Meng et al., 2015; Sivan et al., 2015). In almost all sequenced genomes of mammalian poxviruses, at least one copy of a member from the C7L host range superfamily exists (Liu et al., 2012a; Meng et al., 2008). The host range C7L superfamily is conserved among the family of Poxviridae, and so far, no sequence homologue has been found in host or other pathogens. This suggests a potentially general functional relevance of the mammalian SAMD9 pathway to the life cycle of poxviruses.

Several human diseases have been linked to deletion and deleterious mutations in the SAMD9 gene. Two mutations in SAMD9, a missense K1495E (Topaz et al., 2006) and nonsense R344X (Chefetz et al., 2008) mutations, are responsible for a disease called normophosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis (NFTC) when both alleles are inactivated in the patient. NFTC is an autosomal recessive disorder; patients with NFTC suffer from calcified skin tumors over their extremities and calcium deposits in the mucosa, which are associated with incessant pain and severe infections (Chefetz et al., 2008; Sprecher, 2010; Topaz et al., 2006).

SAMD9 along with two neighboring genes [Miki (Ozaki et al., 2012) and SAMD9L (Nagamachi et al., 2013)], is found within a region of the chromosome 7 long-arm, which frequently undergoes non-random interstitial deletion in patients with myeloid disorders (Asou et al., 2009). Reduced SAMD9 mRNA or protein levels (Li et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2014) are often detected in cancerous tissue, which suggests an inhibitory role of SAMD9 in tumorigenesis.

Most recently, a new form of congenital adrenal hypoplasia, designated MIRAGE (myelodysplasia, infection, restriction of growth, adrenal hypoplasia, genital phenotypes, and enteropathy), was identified and found to be associated with mutations in the SAMD9 gene (Narumi et al., 2016). Narumi et al. (Narumi et al., 2016) found that patients with MIRAGE are young and most of them did not live beyond 2-year of age. Among these patients, mutations in SAMD9 are on a single allele at one dissimilar residue (including 459, 769, 834, 974, 1195, 1280, and 1286) of evolutionarily conserved amino acids in SAMD9 (Narumi et al., 2016). In general, these mutations occur postzygotically and are rarely germline-mosaic (Narumi et al., 2016). Nevertheless, these patients present unusually identical syndromes. Potentially similar cases with this disorder have previously been reported in the literature (Le and Kutteh, 1996; McDonald et al., 2010), albeit without direct confirmation of the genetic links to SAMD9 at the time. The expression of these disease variants in the presence of the wild-type (wt) SAMD9 protein consistently leads to growth restriction in cultured cells (Narumi et al., 2016), suggesting that there is a dominant feature for these mutant proteins compared with the normal function of SAMD9.

Despite these reports on SAMD9’s direct functional importance in cell biology and physiology, the molecular mechanism of SAMD9 function that is interrupted by these mutations remains unknown.

Evolutionary studies showed that SAMD9 and its paralogue, SAMD9-like (SAMD9L), are derived from a common ancestral gene through a duplication event (Lemos de Matos et al., 2013). Despite a similar 60% amino acid identity between human SAMD9 and SAMD9L proteins, unique signatures of positive selection in both genes strongly advocate their distinct functions (Lemos de Matos et al., 2013). Some species harbor only the SAMD9L gene, such as the house mouse, whereas in cow (Bos taurus) and pig (Sus scrofa) species only SAMD9 exists (Lemos de Matos et al., 2013). This suggests a certain redundancy in the functions of SAMD9 and SAMD9L. We reason that SAMD9 and SAMD9L could be involved in related cellular processes. Studying the biological function of SAMD9 has been difficult with the lack of a murine model due to the loss of SAMD9 homolog in mouse genome. Therefore, information related to SAMD9L provides some clues on how SAMD9 performs its cellular functions. SAMD9L is a facilitator of endosomal homotypic fusion and binds to the early endosome protein EEA1, and SAMD9 also shares this feature of binding to EEA1 (Nagamachi et al., 2013). In another study, SAMD9 was shown to interact with RGL2 (Hershkovitz et al., 2011) that is linked to cytokine receptor-associated signaling transduction (Takaya et al., 2007). Thus, it is possible that SAMD9 also plays a role in the endosomal fusion process. Larger vesicles than those found in normal cells can be observed in cells derived from patients with the dominant mutant of SAMD9 (where MIRAGE is present). These vesicles are RAB7A-positive for late endosomes and may be caused by enhanced endosomal fusion (Narumi et al., 2016), which leads to disrupted receptor recycling back to the plasma membrane for continuous signaling transduction. Although these studies provide information about the potential sequence or residue correlation of SAMD9’s intrinsic function, it remains unknown whether the same domain or motif of SAMD9 is responsible for the antiviral function.

The 1589 amino acid sequence of SAMD9 has only two small regions that resemble known domains: a 71-residue sterile α-motif (SAM) domain at the N-terminus and a 152-residue P-loop NTPase domain in the middle. We found previously that an essential host range factor, M062 protein from myxoma virus (MYXV), antagonizes the function of human SAMD9. Deletion of M062R gene in the viral genome resulted in a defective virus that was unable to mount a productive infection due to an activated SAMD9 response. Knocking down SAMD9 protein synthesis rescued M062R-null MYXV infection suggesting a functional antagonism of M062 to SAMD9 (Liu et al., 2011). Considering the fundamental importance of SAMD9 function, we thus utilized MYXV M062 as a probe to examine the regions that are important for the antiviral property of human SAMD9. We also characterize the biophysics and specificity of the interactions between SAMD9 and the viral protein M062. We hypothesize that the N-terminal region of SAMD9, which is targeted by the viral protein, is an important regulatory domain for the intrinsic function of the human protein.

Material and methods

Cell lines and viruses

HeLa (Liu and McFadden, 2015), A549 cells (ATCC CCL-185), HEK-293 (NR-9313 was obtained from the NIH Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Research Resources Repository, NIAID, NIH), and BSC-40 (Liu et al., 2011) were cultured in Dulbecco minimal essential medium (DMEM; LONZA and Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals), 2mM glutamine (Corning), and 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Pen/Strep; Invitrogen). Murine DBT cells (Cai et al., 2007) were cultured in 5% FBS containing DMEM supplemented with glutamine and Pen/Strep as described above. Myxoma viruses [vMyxGFP (wt-like MYXV), vMyxM062RV5 (wt-like MYXV with V5-tagged M062R gene) and vMyxM062RKO (M062R-null MYXV)] and vaccinia virus [VACV-E/LGFP/LtdTr (wt-like VACV) and VACV-C7LK1L-DKO (C7L and K1L double-knockout virus)] were reported previously (Liu and McFadden, 2015; Liu et al., 2011). BSC-40 cells were used for viral stock preparation (36% sucrose ultracentrifugation) and the titration of viral stocks as described previously (Liu et al., 2012b; Liu et al., 2011)).

Cloning, plasmids, and primers

For protein expression in bacteria, the pET28b vector provided by Dr. Chia Lee [University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS)] was used to include SAMD9 fragments by cloning between NdeI and XhoI sites. For mammalian protein expression, a modified pTriEX-4 vector (Cao and Zhang, 2012) containing 3xFLAG at the N-terminal (kindly provided by Dr. Xuming Zhang, UAMS) was used to clone SAMD9 fragments between KpnI and XhoI sites.

To engineer SAMD9-null cells with CRISPR/CAS9 technology, we used pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 (Addgene plasmid #42230) (Kloppmann et al., 2012) and cloned the gRNA1 sequence with following oligo sequences: Forward: 5′-CACCGTAATCCATATCGTTACAAGT-3′; Reverse: 5′-AAACACTTGTAACGATATGGATTAC-3′. We also used pX458-pSpCas9(BB)-T2A-GFP (Addgene plasmid #48138) to clone the gRNA2 sequence targeting SAMD9 with following oligo sequences: Forward: 5′-CACCGTCTCACTATTTGTGGCGAGAT; Reverse: 5′-AAACATCTCGCACAAATAGTGAGAC. After cotransfection of both constructs, single cells that turned green were individually collected via cell sorting and cultured to expand. PCR screening was conducted using primer set 1 (Forward: 5′-aagctgaagcaaatcggaaa-3′; Reverse: 5′-tatgggcatcacacatggac-3′) to examine insertions and deletions (indels) caused by the first gRNA-Cas9. Primer set 2 (Forward: 5′-tttcttctgctgcttttctgg-3′; Reverse: 5′-atgggaaaattgttggcatc-3′) was used to screen for indels caused by the second gRNA-Cas9. Primer set 3 (Forward: 5′-gctgcttttctggactctgc-3′; Reverse: 5′-tatggctaatccgtctgcaa-3′) was used to screen for deletions caused by cleavages at both sites from the first and second gRNA-Cas9 combination. We identified SAMD9-null clones followed by sequencing to confirm the alteration in the genome as previously described (Bauer et al., 2015).

Antibodies and reagents

Primary antibodies include anti-V5 (R96025, ThermoFisher Scientific), SAMD9 (HPA021319, Sigma-Aldrich), SAMD9L (HPA019465, Sigma-Aldrich), β-actin (A1978, Sigma-Aldrich), FLAG (F3165, Sigma-Aldrich), FLAG-HRP (A8592, Sigma-Aldrich), EEA1 (3288S, Cell Signaling Technologies), and TIA-1 (sc1751, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) that were used for immunoprecipitation (IP), Western blotting, and immunofluorescent (IF) staining according to the manufacturer’s standard protocol. Secondary antibodies include goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Jackson ImmunoResearch), goat anti-rabbit HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch), mouse TrueBlot Ultra IgG-HRP (Rockland), donkey anti-mouse AlexaFluor 488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch), donkey anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 594 (Jackson ImmunoResearch), and chicken anti-goat AlexaFluor 647 (Life Technologies).

Protein purification using bacterial expression system

Overexpression was carried out using E.coli BL21-DE3 cells grown in 2X YT Broth supplemented with 34μg/ml kanamycin, or 100mg/mL Ampicillin (Formedium, United Kingdom) at 37 °C. At an OD600 of 0.7 the culture was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG, after which cells were grown for a further 18 hours at 18 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and the pellets were resuspended in His-tag extraction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole and 10mM β-mercaptoethanol [pH 8.0]) (Sigma) along with 0.5 mM PMSF protease inhibitor (Fluka Analytical). Cells were lysed by sonication and the cell lysate was centrifuged at 16000 rpm for 25 minutes at 4 °C to remove any cellular debris. The supernatant was filtered and loaded onto a nickel agarose resin column (QIAGEN). The resin was washed repeatedly with extraction buffer prior to elution of the bound protein using extraction buffer supplemented with 200 mM imidazole. Soluble aggregates were removed by running the eluate through a superdex 200 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in column buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT [pH 7.5]).

Surface plasmon resonance to examine SAMD9-–M062 interaction

Purified SAMD9 (1-385 aa) was coupled to a CM5 chip using a Biacore X100 system (GE Healthcare). Coupling was optimized by scouting a buffer range between pH 4–6 in dilute acetate solutions. For all subsequent binding analyses, the running buffer was 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 0.005% P20, pH 7.4. All SPR experiments were performed at 293K using a common running buffer. Prior to flowing over the CM5-coupled ligands, the purified ‘analytes’ (M062 and M064) were dialyzed in the running buffer to minimize buffer mismatch, and concentrated using iCON centrifuge tubes (Pierce). Data was processed using Biacore X100 Evaluation software, version 2.0. Single-cycle kinetics experiments typically involved concentration ranges from 5–10 times above and below the expected KD (equilibrium dissociation constant).

Transfection and viral infection

Transfection was conducted with ViaFect (Promega) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s standard protocol. To examine the interaction between SAMD9 fragments and the viral M062 protein (24 h after transfection of expression constructs), infection by a wt–like MYXV expressing V5-tagged M062 (Liu et al., 2011) was conducted at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 for 18–24 h before harvesting for IP. To examine the cellular localization of SAMD9 fragments, cells were fixed for further processing at 24 h post-transfection. To test SAMD9 fragments for the antiviral effect, at 24 or 48 h post-transfection (HeLa or HEK293, respectively) cells were infected with M062R-null MYXV, wt MYXV (vMyxGFP), or VACV C7LK1L double knockout (VACV-C7LK1L-DKO) (Liu et al., 2011) for 18 h before harvesting for titration on BSC-40.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

For FLAG pull-down, we used a FLAG Immunoprecipitation Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and followed the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the cell lysate from a 3.5 cm dish was incubated with 10 μL of anti-FLAG M2-Agarose Affinity gel for up to 4 h at 4°C. The bound portion was washed 3 times using buffer containing 50mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, and 150mM NaCl. Bound proteins were eluted by resuspending in the sample buffer with β-mercaptoethanol and heat denaturing at 90°C for 5 min. To conduct V5 pull-down experiments, we used a protocol that was described previously (Liu et al., 2011). Briefly, cell lysate was pre-cleared with blank agarose beads (high-capacity Pierce Protein A/G Agarose resin, ThermoFisher Scientific), and then incubated with V5 antibody-loaded beads (anti-V5 tag antibody agarose, Abcam) for up to 4 h before extensive washing and elution using sample buffer. For general Western blot, equal amount of protein (estimated with Quick Start Bradford 1× Dye Reagent, Bio-Rad) was loaded on SDS-PAGE for separation by molecular mass. After transferring to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, the blot was blocked with 5% nonfat milk resuspended in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) and incubated overnight with appropriate amount of primary antibody (1:5000 for anti-V5 antibody; 1:2000 dilution for anti-FLAG M2 antibody) at 4°C. Extensive wash and incubation with the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody were performed before washing and adding substrate (Clarity Max Western ECL Substrate, Bio-Rad) for imaging (Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP System) or exposing on x-ray films (Research Products International).

Immunofluorescent staining and image capture using fluorescent microscopy

Procedure for IF staining and image capture was described previously (Liu and McFadden, 2015). Briefly, cells were seeded on cover glass (Thomas Scientific) the day before transfection. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature followed by washing with PBS. Cells were permeablized with ice-cold methanol at −20°C for 5 min followed by 2 washes with PBS. Cells were blocked with 10% FBS-PBS at 4°C overnight before they are stained with antibodies. Primary antibodies, FLAG M2 (1:500), EEA1 (1:300), and TIA-1 (1:50) were diluted in 2% FBS-PBS to incubate at room temperature for 1 h before 3 washes with PBS. Secondary antibodies, donkey anti-mouse AlexaFluor 488 (1:200), donkey anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 594 (1:200), and chicken anti-goat AlexaFluor 647 (1:500), were diluted in 2% FBS-PBS to incubate at room temperature for 1 h before 3 washes with PBS. Cover glasses were then stained with DAPI and mounted with SlowFade Diamond Antifade Mountant (ThermoFisher Scientific). A Nikon C2 confocal microscope (Nikon) was used to visualize the fluorescent staining and images were acquired using a 100× oil-objective lens controlled by NIS-Elements software. Images were acquired using each laser (405, 488, 561, and 640 nm) and exported to JPEG format with NIS-Elements software with scale bars.

Statistic analysis

Statistical significance, e.g., one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test, and multiple t tests followed by the Holm–Sidak method, was determined using GraphPad Prism 6.0h.

Results

Generation of SAMD9-null cell lines

There is little information about the domain organization of human SAMD9 protein due to the absence of sequence conservation to known proteins. Nevertheless, the importance of human SAMD9 in development (Narumi et al., 2016), stress response (Liu and McFadden, 2015), host defense (Liu et al., 2011; Meng et al., 2015; Narumi et al., 2016; Sivan et al., 2015), inflammatory homeostasis (Chefetz et al., 2008; Topaz et al., 2006), and anti-neoplasm (Asou et al., 2009; Li et al., 2007) has been recognized.

To examine the interaction between exogenously expressed SAMD9 fragments and the viral M062 protein, we engineered a SAMD9-null HeLa cell line with CRISPR/CAS9 technology. As shown in Figure 1B, full-length SAMD9 expression is completely ablated, whereas the expression of an immediate neighbor gene SAMD9L remains intact and comparable to that in the parental cells. Sequencing results show that a single deletion of adenosine (A) at 527 bp of the SAMD9 coding sequence (CDS) is caused by the cleavage from the gRNA1-Cas9 construct (Fig. 1A). This single deletion in the CDS causes a frame shift that generates a stop codon, which is predicted to produce a 212 aa protein. Because the antibody recognizing SAMD9 is raised against the first 82 amino acids of the protein we overexposed the film of Western blot (Fig. 1B), but could not visualize the presence of the truncated protein (not shown). It is possible that the truncated protein produced in engineered cells may not be stable. Furthermore, we confirmed that the SAMD9-null HeLa cell rescues the abortive infection caused by both M062R-null MYXV (Fig. 1C) and double-knockout VACV of C7L and K1L genes (Supplemental Fig. 1). Among three independent SAMD9-null cell lines, comparable phenotypes were observed. Moreover, no significant difference is observed in wt MYXV infection in the presence or absence of SAMD9 (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Characterization of the SAMD9-null cell line.

A. Sequence confirmation of engineered SAMD9-null HeLa cell clone. Sequencing of genomic DNA of SAMD9-null cells shows a single deletion of adenosine caused by the first gRNA-Cas9 construct corresponding to a residue at 527 nt in the SAMD9 CDS. B. Characterization of engineered SAMD9-null HeLa cells. Western blot results show the absence of the full-length SAMD9 protein, whereas SAMD9L (a gene located immediately next to SAMD9 on the same chromosome) is comparable in the parental (lane 1) and SAMD9-null B3 clone (lane 2) HeLa cells. Thirty micrograms of protein from either the parental (lane 1) or SAMD9-null clone B3 (lane 2) HeLa cells were separated on SDS-PAGE for Western blot. Protein levels of β-actin in each sample show a comparable level of protein loaded for each sample. C. Characterization of SAMD9-null HeLa cells with M062R-null MYXV. A multiple-step growth test using either wt MYXV or M062R-null MYXV was conducted using parental HeLa and two clones of SAMD9-null cells, B3 and E3. Viral infection was conducted at MOI 0.1 and at given time points (1, 7, 24, 48, and 72 h) cell lysates were collected for titration on BSC-40 cells. A representative curve of two independent experiments is shown. D. Comparison of infection by wt MYXV in parental and SAMD9-null HeLa cells. Infection was conducted at MOI 0.1 in either parental or two independent clones of SAMD9-null cells, B3 and E3. As a control for abortive infection, similar infection using M062R-null MYXV was conducted in parental HeLa cells. A multiple-step growth curve of wt MYXV in either parental or SAMD9-null HeLa cells is shown. A representative result of two independent experiments is shown.

We used algorithms to predict secondary structure for possible separation of potential domains in the SAMD9 protein. Following analyses, we expressed smaller segments of SAMD9 to gain insight into sequence and function relationships (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Identification of the SAMD9 region that is bound by MYXV M062.

A. Cloning fragments of human SAMD9. We designed the cloning of SAMD9 fragments with the prediction that can best preserve the extrapolated secondary structure. Sequences of the CDS, which correspond to the amino acid sequence shown in the diagram, were cloned in the expression plasmids for bacterial (pET28) or mammalian (modified pTriEx vector containing N-terminal 3xFLAG) expression. B. MYXV M062 binds to an N-terminal fragment of SAMD9. Cells lack of the SAMD9 protein were transfected with constructs as shown. Infection by a wt–like MYXV expressing V5-tagged M062 was conducted 24 h post-transfection at MOI 1 for 24 h. Cell lysates were harvested for immunoprecipitation using anti-V5 antibody. Only 25% bound portion of SAMD91-385 and 50% bound portion of full-length SAMD9 were loaded on the gel, while 100% bound protein was loaded for the rest of samples. Bound SAMD9 fragments were confirmed using anti-FLAG antibody. Input proteins are shown at the bottom. In all input samples 3% of total cell lysate was loaded on the gel except for SAMD9390-1170 (Lane 5) that 6% of total cell lysate was shown. Lane 1: mock transfected; Lane 2: empty vector plasmid transfected; 3: full-length SAMD9 (expected 190 KDa); 4: SAMD91170-c terminus (53 KDa); 5: SAMD9390-1170 (95 KDa); 6: SAMD91-385 (49 KDa). C. M062 is bound to SAMD91-385. HeLa cells engineered to delete SAMD9 expression were transfected with corresponding plasmids encoding fragments of SAMD9 as indicated. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were infected with MYXV engineered to express V5-tagged M062 protein at MOI 1 for 24 h. Cells were then harvested to collect cell lysates for immunoprecipitation using FLAG antibody conjugated resin. The presence of bound V5-tagged M062 was confirmed with anti-V5 antibody. Input of either SAMD9 fragments (anti-FLAG) or M062 (anti-V5) are shown using 5% of the total lysate. Lane 1: Empty plasmid transfected; Lane 2: SAMD91-110 (17 KDa); Lane 3: SAMD978-285 (28 KDa); Lane 4: SAMD91-385. In the pull-down blot, “*” marks the detection of V5 tagged M062, while light chain of the antibody used for pull-down can be seen above in all four lanes.

Mapping of SAMD9-M062 interactions

To identify the SAMD9 segment that is bound by MYXV M062, we transfected the constructs expressing different segments of SAMD9 (Fig. 2A) into the SAMD9-null HeLa cells followed by infection with a wt–like MYXV expressing the V5-tagged M062 protein. We also conducted similar experiments in HeLa cells with the SAMD9 knockdown, which expresses SAMD9 shRNAs as previously described (Liu et al., 2011), and in the mouse cell line with DBT, which does not express the SAMD9 protein (not shown). In these experiments, we observed the same interactions. We found that the N-terminal fragment of 1-385 aa of SAMD9 (SAMD91-385) retains the ability to interact with viral M062 (Fig. 2B). Pull-down experiments of either M062 (V5) (Fig. 2B) or SAMD9 fragments (FLAG, Supplemental Fig 2) show the same outcome. Furthermore, to examine the interaction within the SAMD91-385 fragment, we found that SAMD91-110 (SAM domain) and SAMD978-285 fragments do not interact with viral M062 (Fig. 2C).

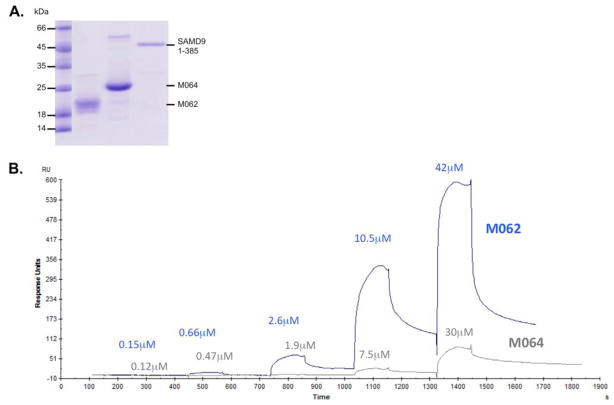

To investigate whether there is direct binding between viral M062 and the SAMD91-385 we examined the interaction in vitro. As a control, we tested the viral M064 protein, which is another MYXV homologue of the C7L host range superfamily. M064 (NP_051778.1) shares 41.3% of the amino acid identity with M062 (P68550.1) (http://web.expasy.org/sim/). However, a previous study showed that M064 is not a host range determinant but rather a virulence factor (Liu et al., 2012b). We purified viral M062, viral M064, and the SAMD91-385 (Fig. 3A). Then we conducted the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analyses. SAMD91-385 was coupled to a CM5 chip (see METHODS) and various concentrations of either viral M062 or M064 were injected over the surface to measure binding (Fig. 3B). It was observed that M062, but not M064, was able to bind to CM5-coupled SAMD91-385 (Fig. 3B), The equilibrium binding affinity (KD) was calculated to be 10±5 μM from multiple independent experiments.

Figure 3. Confirmation of the direct interaction between M062 and SAMD9.

A. Purified viral and host proteins for SPR analysis. For SPR experiments, proteins MYXV M062, M064, and the 1-385 aa of SAMD9 were purified as described in Materials and Methods. Analysis for purity was performed by running a 15% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions (shown). There are small impurities that do not significantly affect the experiments. B. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analyses of M062 binding to SAMD9. Binding of M062 was analyzed using multiple injections of the viral protein onto CM5-immobilized SAMD91-385. The set of 5 injections at increasing concentrations were performed in ‘single-cycle’ mode (Biacore X100 Evaluation software, version 2.0), without regeneration steps. M064 protein binding was analyzed as a control at similar concentrations. Data were fit to a 1:1 equilibrium binding model, and equilibrium affinity was also independently verified by fitting the curves for estimates of kon and koff.

Given that one of the clearly recognized regions of SAMD9 is the N-terminal SAM motif (residues 10-78), we investigated whether it is this short segment that enables binding to M062. M062 was purified and coupled to a CM5 chip, and SAMD910-78 and SAMD91-385 were injected over the derivatized chip to evaluate binding (Supplemental Fig. 3). It was observed that while SAMD91-385 exhibited strong binding, SAMD910-78 injections revealed small increases that could mostly be ascribed to bulk refractive index changes. Therefore, the N-terminal SAM motif does not significantly bind to M062.

Functional analyses of SAMD9 regions

Because the SAMD9 protein is absent in engineered SAMD9-null cells, we can examine the functionality of SAMD9 fragments in terms of antiviral activities. We reason that if a domain or motif within SAMD9 possesses a stand-alone antiviral effect, we would detect inhibition of viral replication by either M062R-null MYXV or VACV lacking both C7L and K1L genes. We transfected fragments of SAMD9 in SAMD9-null HeLa cells followed by infection with either vMyxM062RKO (Fig. 4A) or VACV-C7LK1L-DKO (Fig. 4B). We found that only the full-length SAMD9 significantly inhibits viral replication of both viruses. In vMyxM062RKO infection, the full-length protein reduced slightly more than 50% of progeny production (Fig. 4A). However, the magnitude of inhibition by the full-length protein of SAMD9 is approximately a log difference compared with the empty vector transfected or other SAMD9 fragments in VACV-C7LK1L-DKO infected cells (Fig. 4B). A dose–response study was conducted to test whether the antiviral effect of the full-length protein is associated with infection at certain MOIs. We found that the full-length protein potently inhibits VACV-C7LK1L-DKO infection at a MOI of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 by 84%, 71%, 78%, and 83%, respectively (Supplemental Fig 4B). In a similar test with a fixed amount of transfected full-length SAMD9, using escalating doses of MYXV infection (MOI of 1, 2, 5, and 10) we also detected a significant antiviral effect of the full-length SAMD9 (56%, 38%, 77%, and 78%, respectively) (Supplemental Fig 4A).

Figure 4. Exogenously expressed full-length SAMD9 restores the antiviral effect in SAMD9-null cells.

A. Full-length SAMD9 inhibits M062R-null MYXV infection in SAMD9-null cells. SAMD9-null HeLa cells were transfected with the empty vector, full-length protein, and fragments of SAMD9, respectively. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were infected with vMyxM062RKO for up to 18 h before cell lysates were harvested for titration. Duplicate of technical replicate per construct were conducted for transfection followed by infection at an MOI of 1 in each biological replicate. Titration was conducted by serial dilutions of cell lysate and triplicate in each dilution. Shown is a representative result of four independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA with alpha=5.0% showed significance in column factor (p<0.01) (different constructs). Multiple comparisons were conducted with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test with alpha=0.05 (**: p<0.01). B. Full-length SAMD9 potently inhibits infection by the double-knockout VACV of C7L and K1L in SAMD9-null cells. Similar to the experiment in A, after transfection, infection with VACV-C7LK1L-DKO at an MOI of 0.1 was conducted for up to 18 h before titration. Single wells of cells were transfected with constructs as shown followed by infection. Shown is a representative result of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA (Alpha=0.05) showed statistically significant difference between treatments (p<0.01). Multiple comparisons were conducted using Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (**: p<0.01).

To examine whether an interaction between viral M062 and SAMD91-385 is functional, we overexpressed SAMD91-385 before infection with a wt MYXV, and then tested whether an inhibition of viral replication could be observed. Indeed, we detected a statistically significant reduction in progeny virus production against wt MYXV infection (Fig. 5) when both the full-length and SAMD91-385 were exogenously expressed. In HEK293 cells, vMyxM062RKO infection is abortive, which is consistent with the SAMD9 effect in most human cell lines (Liu et al., 2011). Overexpression of full-length SAMD9 likely enhances the antiviral effect that is already intrinsically present in the cells by endogenous SAMD9 and the function of M062 protein may be diluted due to the additional full length SAMD9. We reason that the inhibitory effect by SAMD91-385 is due to the sequestration of M062 during viral infection, making it unavailable to antagonize the endogenous SAMD9 protein.

Figure 5. Overexpression of SAMD91-385 inhibits wt MYXV infection.

SAMD91-385 and full-length SAMD9 inhibit wt MYXV infection. HEK293 cells were transfected with an empty vector, full-length, or SAMD91-385, respectively. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were infected with wt MYXV (MOI 1) for 18 h before cell lysates were harvested for titration. Shown is a summary of the experiment that contains triplicates in transfection of each construct and is representative of two independent experiments.

We conducted IF staining to examine the cellular localization of SAMD9 fragments when they are expressed exogenously in SAMD9-null HeLa cells. We found that a generally cytoplasmic distribution of each SAMD9 fragment (Fig. 6 and not shown for SAMD390-1179 and SAMD1170-c terminus), with (1-285 aa) or without the SAM domain (78-285 aa), affects the N-terminal fragment of SAMD9 to form aggregates.

Figure 6. Cellular localization of exogenously expressed SAMD9 fragments.

Cells were transfected up to 28 h with respective constructs (FLAG-tagged) as labeled before cells were fixed and permeablized for immunofluorescent staining. FLAG tagged protein is labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (green), EEA1 is labeled with Alexa Fluor 594 (red), and TIA-1 is labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 (violet). Images were captured with Nikon C2 confocal microscope using a 100× oil-objective lens controlled by NIS-Elements software. Scale bar represents 50 μm. The set of inserts were acquired by using an 8.92 zoom.

Discussion

When full-length SAMD9 is exogenously overexpressed via transfection, we observe the formation of aggregation (Fig 6). Within these SAMD9-driven aggregates, we detected other stress granule (SG) components, such as TIA-1, co-localized (Fig 6). In SAMD9-null cells, however, SG formation was not affected, at least not by oxidative stress or pateamine a (Pat A) analog (eIF4A inhibitor) treatment (not shown). Thus, we conclude that SAMD9 is not directly responsible for SG formation under these conditions.

The observation that the SAM domain of SAMD9 may play a role in the formation of granule structure (Fig 6, SAMD91-285 and SAMD78-285) is in agreement with the conclusion from a previous proteomic study, where it predicted and demonstrated the ability for this domain to form polymers (Knight et al., 2011). Extending the sequence of SAMD91-285 by an additional 100 residues, as in the SAMD91-385, abolishes the polymerization ability of the SAM domain (compared with SAMD91-285 in Fig. 6).

While the fragment SAMD91-285 is unable to bind M062, the slightly longer fragment SAMD91-385 recovers the ability to interact with M062 (Fig. 2C). It cannot be ruled out that other regions of SAMD9 also contribute to M062 recognition, since we are unable to purify the full-length SAMD91-1589 and perform biophysical analyses to compare affinities. However, strong in vitro and cellular binding, together with a measured affinity of 10 μM from surface plasmon resonance analyses, suggest that the core M062-binding region is SAMD91-385.

We detect no stand-alone function in terms of antiviral effect against either M062R-null MYXV or double-knockout VACV of C7L and K1L when SAMD91-385 is transfected into human cells that are void of SAMD9 full-length protein synthesis (Fig. 4A, B). This indicates that, at least within the 1-385 aa fragment, there is not an independent enzymatic domain or other functional motif that is linked to MYXV and VACV infections. Thus, we hypothesize that SAMD91-385 possesses a regulatory function that is essential to MYXV infection. This model is consistent with our findings that only a full-length SAMD9 protein is capable of an antiviral effect against infection by either M062R-null MYXV or double-knockout VACV lacking C7L and K1L in the SAMD9-null HeLa cells (Fig. 4A, B).

When full-length SAMD9 transfected SAMD9-null HeLa cells were infected with VACV-C7LK1L-DKO and vMyxM062RKO, a potent inhibition of viral replication was consistently detected (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Fig 4). Vaccinia virus replication in human cells is much more efficient than that of MYXV. An average of 1 log higher in infectious viral particle production per cell can be observed in VACV than in MYXV infection, at least in HeLa cells (Fig. 1C and Supplemental Fig. 1). It is noted that transfection of a plasmid significantly inhibits MYXV in HeLa cells, whereas the effect on VACV infection is less noticeable. Much higher MOI is needed for MYXV infection than VACV to test SAMD9 function expressed from a plasmid. The inhibition of viral replication by plasmid transfection is likely due to the triggering of cGAS via STING (Langereis et al., 2015); it is possible that VACV evades this antiviral state more effectively than MYXV in human cells.

The antiviral effect of transfected SAMD9 on MYXV infection is likely the sum of both the SAMD9 effect and cGAS/STING activation by DNA transfection. This complicates the testing system to examine SAMD9’s antiviral effect against MYXV and to compare the response from these two viruses in some human cells. We also cannot rule out potentially different modes of antagonism to the SAMD9 antiviral effect by VACV and MYXV. Finally, it remains intriguing that we observed such potent antiviral effects from SAMD9 to both viruses in SAMD9-null HeLa cells. Considering the low efficiency in both transfection and exogenous synthesis of a large protein like full-length SAMD9, the antiviral effect rendered by restoring full-length SAMD9 seems to have a profound effect on cells. Further studies are underway to understand the downstream cellular events triggered by SAMD9 activation.

Supplementary Material

VACV infection, wt VACV, or double-knockout VACV of C7L and K1L, was conducted at MOI 0.01 in either parental or SAMD9-null HeLa cells (clones E3 and G3). At given time points, cell lysates are harvested for titration on BSC-40 cells. A representative experiment with titration in triplicate is shown.

Similar to the experiment in Figure 2B, SAMD9-null cells were transfected with an empty vector, a plasmid expressing SAMD91-110,, SAMD978-285, or SAMD91-385 for 24 h before infection with M062V5 expressing MYXV at MOI 1 for 24 h. Cell lysates were harvested for immunoprecipitation with anti-V5 antibody and Western blot was conducted to probe against FLAG-tagged protein. Five percent of total lysate was used for the input blot shown on the right. The presence of M062V5 and FLAG-tagged SAMD9 fragments in the input samples are shown by Western blot.

A. SAMD91-385 injected over M062-CM5 chip; B. SAMD910-78 (SAM domain) injected over the same chip. Various concentrations of purified SAMD9 are indicated, and an identical y-scale is shown to emphasize the relative binding of the two SAMD9 fragments to the viral protein. The SPR signal was recorded using a BiaCore X-100 instrument (GE Healthcare).

Full-length SAMD9 was transfected in SAMD9null-HeLa for 24 hrs before cells were infected with either vMyxM062RKO (A) or VACV-C7LK1L-DKO (B) at given MOIs. At 24 hrs post-infection, cell lysates were harvested and titers were evaluated on BSC-40 cells. Statistical significance was determined with multiple t tests and Holm-Sidak method with alpha=5.000% (**: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001).

Hightlights.

SAMD9, a large cytoplasmic protein, is important for human health but its mode of action is unknown.

We examined SAMD9 domains for their antiviral property.

We confirmed the direct interaction between SAMD9 and viral M062 from myxoma virus.

We are the first to characterize the sequence-domain relation of human SAMD9 using a viral antagonizer.

Acknowledgments

All authors declare no conflict of interest on this work that has been conducted. This work was supported in part by K22-A99184, P20-GM103625, and a start-up fund by the UAMS Department of Microbiology and Immunology (MBIM) to J. Liu. The sequencing and flow cytometry core services are supported in part by the Translational Research Institute (TRI), grant UL1TR000039 through the NIH National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and by the Center for Microbial Pathogenesis and Host Inflammatory Responses grant P20GM103625 through the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence. We thank J Liem, S Blair, J Cao, and S Chancellor for technique assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson P, Kedersha N. Stress granules: the Tao of RNA triage. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2008;33:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asou H, Matsui H, Ozaki Y, Nagamachi A, Nakamura M, Aki D, Inaba T. Identification of a common microdeletion cluster in 7q21.3 subband among patients with myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2009;383:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DE, Canver MC, Orkin SH. Generation of genomic deletions in mammalian cell lines via CRISPR/Cas9. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE. 2015 doi: 10.3791/52118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Liu Y, Zhang X. Suppression of coronavirus replication by inhibition of the MEK signaling pathway. Journal of virology. 2007;81:446–456. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01705-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Zhang X. Comparative in vivo analysis of the nsp15 endoribonuclease of murine, porcine and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses. Virus research. 2012;167:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chefetz I, Ben Amitai D, Browning S, Skorecki K, Adir N, Thomas MG, Kogleck L, Topaz O, Indelman M, Uitto J, Richard G, Bradman N, Sprecher E. Normophosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis is caused by deleterious mutations in SAMD9, encoding a TNF-alpha responsive protein. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2008;128:1423–1429. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkovitz D, Gross Y, Nahum S, Yehezkel S, Sarig O, Uitto J, Sprecher E. Functional characterization of SAMD9, a protein deficient in normophosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2011;131:662–669. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha NL, Gupta M, Li W, Miller I, Anderson P. RNA-binding proteins TIA-1 and TIAR link the phosphorylation of eIF-2 alpha to the assembly of mammalian stress granules. The Journal of cell biology. 1999;147:1431–1442. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloppmann E, Punta M, Rost B. Structural genomics plucks high-hanging membrane proteins. Current opinion in structural biology. 2012;22:326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight MJ, Leettola C, Gingery M, Li H, Bowie JU. A human sterile alpha motif domain polymerizome. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society. 2011;20:1697–1706. doi: 10.1002/pro.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langereis MA, Rabouw HH, Holwerda M, Visser LJ, van Kuppeveld FJ. Knockout of cGAS and STING Rescues Virus Infection of Plasmid DNA-Transfected Cells. Journal of virology. 2015;89:11169–11173. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01781-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le SQ, Kutteh WH. Monosomy 7 syndrome associated with congenital adrenal hypoplasia and male pseudohermaphroditism. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1996;87:854–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos de Matos A, Liu J, McFadden G, Esteves PJ. Evolution and divergence of the mammalian SAMD9/SAMD9L gene family. BMC evolutionary biology. 2013;13:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CF, MacDonald JR, Wei RY, Ray J, Lau K, Kandel C, Koffman R, Bell S, Scherer SW, Alman BA. Human sterile alpha motif domain 9, a novel gene identified as down-regulated in aggressive fibromatosis, is absent in the mouse. BMC genomics. 2007;8:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, McFadden G. SAMD9 is an innate antiviral host factor with stress response properties that can be antagonized by poxviruses. Journal of virology. 2015;89:1925–1931. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02262-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Rothenburg S, McFadden G. The poxvirus C7L host range factor superfamily. Current opinion in virology. 2012a;2:764–772. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wennier S, Moussatche N, Reinhard M, Condit R, McFadden G. Myxoma virus M064 is a novel member of the poxvirus C7L superfamily of host range factors that controls the kinetics of myxomatosis in European rabbits. Journal of virology. 2012b;86:5371–5375. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06933-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wennier S, Zhang L, McFadden G. M062 is a host range factor essential for myxoma virus pathogenesis and functions as an antagonist of host SAMD9 in human cells. Journal of virology. 2011;85:3270–3282. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02243-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Yu T, Ren YY, Gong T, Zhong DS. Overexpression of SAMD9 suppresses tumorigenesis and progression during non small cell lung cancer. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2014;454:157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald S, Wilson DB, Pumbo E, Kulkarni S, Mason PJ, Else T, Bessler M, Ferkol T, Shenoy S. Acquired monosomy 7 myelodysplastic syndrome in a child with clinical features suggestive of dyskeratosis congenita and IMAGe association. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2010;54:154–157. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Chao J, Xiang Y. Identification from diverse mammalian poxviruses of host-range regulatory genes functioning equivalently to vaccinia virus C7L. Virology. 2008;372:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Krumm B, Li Y, Deng J, Xiang Y. Structural basis for antagonizing a host restriction factor by C7 family of poxvirus host-range proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:14858–14863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515354112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamachi A, Matsui H, Asou H, Ozaki Y, Aki D, Kanai A, Takubo K, Suda T, Nakamura T, Wolff L, Honda H, Inaba T. Haploinsufficiency of SAMD9L, an endosome fusion facilitator, causes myeloid malignancies in mice mimicking human diseases with monosomy 7. Cancer cell. 2013;24:305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narumi S, Amano N, Ishii T, Katsumata N, Muroya K, Adachi M, Toyoshima K, Tanaka Y, Fukuzawa R, Miyako K, Kinjo S, Ohga S, Ihara K, Inoue H, Kinjo T, Hara T, Kohno M, Yamada S, Urano H, Kitagawa Y, Tsugawa K, Higa A, Miyawaki M, Okutani T, Kizaki Z, Hamada H, Kihara M, Shiga K, Yamaguchi T, Kenmochi M, Kitajima H, Fukami M, Shimizu A, Kudoh J, Shibata S, Okano H, Miyake N, Matsumoto N, Hasegawa T. SAMD9 mutations cause a novel multisystem disorder, MIRAGE syndrome, and are associated with loss of chromosome 7. Nature genetics. 2016;48:792–797. doi: 10.1038/ng.3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki Y, Matsui H, Asou H, Nagamachi A, Aki D, Honda H, Yasunaga S, Takihara Y, Yamamoto T, Izumi S, Ohsugi M, Inaba T. Poly-ADP ribosylation of Miki by tankyrase-1 promotes centrosome maturation. Molecular cell. 2012;47:694–706. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reineke LC, Dougherty JD, Pierre P, Lloyd RE. Large G3BP-induced granules trigger eIF2alpha phosphorylation. Molecular biology of the cell. 2012;23:3499–3510. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-05-0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reineke LC, Lloyd RE. The stress granule protein G3BP1 recruits protein kinase R to promote multiple innate immune antiviral responses. Journal of virology. 2015;89:2575–2589. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02791-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivan G, Ormanoglu P, Buehler EC, Martin SE, Moss B. Identification of Restriction Factors by Human Genome-Wide RNA Interference Screening of Viral Host Range Mutants Exemplified by Discovery of SAMD9 and WDR6 as Inhibitors of the Vaccinia Virus K1L-C7L- Mutant. mBio. 2015;6:e01122. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01122-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher E. Familial tumoral calcinosis: from characterization of a rare phenotype to the pathogenesis of ectopic calcification. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2010;130:652–660. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaya A, Kamio T, Masuda M, Mochizuki N, Sawa H, Sato M, Nagashima K, Mizutani A, Matsuno A, Kiyokawa E, Matsuda M. R-Ras regulates exocytosis by Rgl2/Rlf-mediated activation of RalA on endosomes. Molecular biology of the cell. 2007;18:1850–1860. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topaz O, Indelman M, Chefetz I, Geiger D, Metzker A, Altschuler Y, Choder M, Bercovich D, Uitto J, Bergman R, Richard G, Sprecher E. A deleterious mutation in SAMD9 causes normophosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis. American journal of human genetics. 2006;79:759–764. doi: 10.1086/508069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

VACV infection, wt VACV, or double-knockout VACV of C7L and K1L, was conducted at MOI 0.01 in either parental or SAMD9-null HeLa cells (clones E3 and G3). At given time points, cell lysates are harvested for titration on BSC-40 cells. A representative experiment with titration in triplicate is shown.

Similar to the experiment in Figure 2B, SAMD9-null cells were transfected with an empty vector, a plasmid expressing SAMD91-110,, SAMD978-285, or SAMD91-385 for 24 h before infection with M062V5 expressing MYXV at MOI 1 for 24 h. Cell lysates were harvested for immunoprecipitation with anti-V5 antibody and Western blot was conducted to probe against FLAG-tagged protein. Five percent of total lysate was used for the input blot shown on the right. The presence of M062V5 and FLAG-tagged SAMD9 fragments in the input samples are shown by Western blot.

A. SAMD91-385 injected over M062-CM5 chip; B. SAMD910-78 (SAM domain) injected over the same chip. Various concentrations of purified SAMD9 are indicated, and an identical y-scale is shown to emphasize the relative binding of the two SAMD9 fragments to the viral protein. The SPR signal was recorded using a BiaCore X-100 instrument (GE Healthcare).

Full-length SAMD9 was transfected in SAMD9null-HeLa for 24 hrs before cells were infected with either vMyxM062RKO (A) or VACV-C7LK1L-DKO (B) at given MOIs. At 24 hrs post-infection, cell lysates were harvested and titers were evaluated on BSC-40 cells. Statistical significance was determined with multiple t tests and Holm-Sidak method with alpha=5.000% (**: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001).