Abstract

CR6-interacting factor 1 (CRIF1) was previously identified as a nuclear protein that interacts with members of the Gadd45 family and plays a role as a negative regulator in cell growth. However, the nuclear function of CRIF1 remains largely unknown. In this study, we demonstrate that CRIF1 acts as a novel corepressor of the androgen receptor (AR) in prostatic cells. Transient transfection studies show that CRIF1 specifically represses AR transcriptional activation of target promoters in a dose-dependent manner. Additionally, CRIF1 is recruited with AR to the endogenous AR target promoters. In vivo and in vitro protein interaction assays reveal that CRIF1 directly interacts with AR via the activation function-1 domain of AR. Interestingly, both the N-terminal and C-terminal half-regions of CRIF1 are independently capable of interacting with and repressing the transactivation of AR. CRIF1 represses AR transactivation through competition with AR coactivators. In addition, the CRIF1-mediated inhibition of AR transactivation involves the recruitment of histone deacetylase 4. Down-regulation of CRIF1 by small interfering RNA increases the transactivation of AR and the mRNA level of the AR target gene prostate-specific antigen, whereas the overexpression of CRIF1 decreases the prostate-specific antigen mRNA level. Finally, the overexpression of CRIF1 inhibits the androgen-induced proliferation and cell cycle progression of prostate cancer cells. Taken together, these results suggest that CRIF1 acts as an AR corepressor and may play an important role in the regulation of AR-positive growth of prostate cancer.

CR6-INTERACTING FACTOR 1 (CRIF1) interacts with the Gadd45 (growth arrest and DNA damage inducible) family of proteins and suppresses cell cycle progression through the inhibition of Cdc2/cyclin B1 and Cdk2/cyclin E kinase activity and the alteration of Rb phosphorylation (1). CRIF1 is ubiquitously expressed in endocrine organs such as the adrenal gland, thyroid gland, testis, and ovary, and the protein is mainly localized in the nuclear compartment (1). CRIF1 has previously been shown to inhibit the transactivation of orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 through direct interaction in thyroid cells, which suggests its role as a coregulator of nuclear receptors (2). CRIF1 inhibits steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-2-mediated Nur77 transactivation, Nur77-dependent E2F1 gene expression, and Nur77-mediated G1/S progression in thyroid cells (2) and was also recently reported to interact with the casein kinase II β-subunit, which is phosphorylated by casein kinase II. The phosphorylation of CRIF1 promotes cell proliferation in COS-7 cells, suggesting the involvement of CRIF1 phosphorylation in cell proliferation (3). Although there have been some reports that CRIF1 regulates cell proliferation and cell cycle progression in certain types of cells, detailed functions of CRIF still largely remain to be determined.

Androgens and androgen receptor (AR) play important roles in the development, maintenance, and function of the prostate (4, 5). Prostatic bud is not formed in the organ culture of urogenital sinus from the AR-deficient Tfm mice (6), and the prostate shows agenesis in AR knockout mice (7). Moreover, androgen deprivation in adult male animals causes the regression of the prostate, and subsequent androgen supply induces the regeneration of the regressed prostate (8). AR is also an important mediator in the progression and survival of prostate cancers (9). AR is expressed in primary prostate cancer and is detected throughout the progression of cancer in both androgen-dependent and androgen-independent prostate cancers (10, 11, 12). Although prostate cancers progress from being androgen dependent to being androgen independent, it is still believed that AR has an important function in both types of prostate cancer. Indeed, a previous study showed that androgen-dependent PC-82 human prostate cancer cells did not grow when the cells were xenografted into AR-null male Tfm nude mice (13). Moreover, several studies have shown that knockdown of the AR gene by small interfering RNA (siRNA) decreases prostate-specific antigen (PSA) expression and cell proliferation in both androgen-dependent and androgen-independent prostate cancer cells (14, 15, 16).

AR is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily and is also a ligand-dependent transcription factor. AR shares a characteristic structure with other steroid hormone receptors and contains three distinct functional domains: a variable N-terminal activation function-1 domain (AF-1), a central DNA-binding domain (DBD), and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD) (17). The binding of ligands induces a change in the conformation of AR and its subsequent translocation into nucleus, where it regulates the expression of its target genes (18, 19). Transcriptional regulation of AR is modulated by coactivators and corepressors. Coactivators potentiate ligand-dependent transactivation of the receptor with diverse modes of action, including direct interaction with basal transcription machinery and covalent modification of histones and other proteins (20, 21, 22, 23). Corepressors have also been shown to negatively regulate AR transactivation through diverse mechanisms. They induce the alteration of the chromatin structure by recruiting histone deacetylase, or they may inhibit the coactivator recruitment to the receptor complex (24, 25, 26, 27). Corepressors may also inhibit nuclear translocation and DNA binding of AR (28, 29).

Here, we investigated the role of CRIF1 in the modulation of AR transcriptional activity in prostatic cells. We demonstrate that CRIF1 inhibits AR transactivation through direct physical interaction. Interestingly, CRIF1 represses AR transactivation both by outcompeting AR coactivators and by actively recruiting histone deacetylase (HDAC). Moreover, overexpression of CRIF1 decreases the mRNA level of AR-responsive gene and also inhibits the proliferation and cell cycle progression of prostate cancer cells. This report may provide new insight into the function of CRIF1 in prostatic cells.

RESULTS

CRIF1 Represses the Transactivation of AR and Is Recruited with AR onto AR Target Promoters

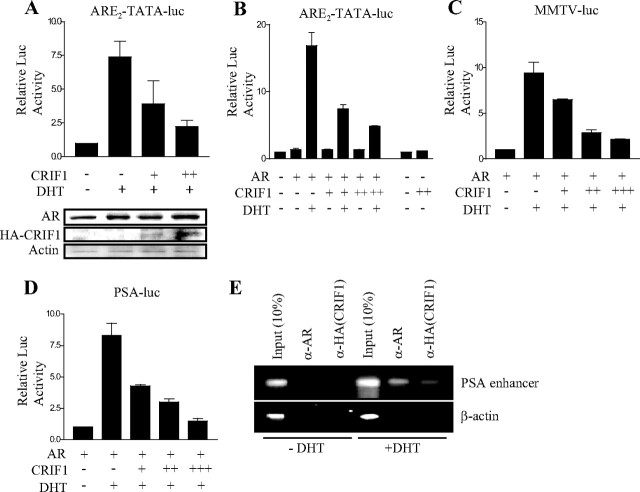

An earlier study showed that CRIF1 interacts with the orphan nuclear receptor Nur77, thereby repressing the transactivation of Nur77 (2). The same study also revealed that CRIF1 physically associates with AR as well as Nur77, which suggests the possibility that CRIF1 modulates the function of AR. Thus, we initially investigated the effect of CRIF1 on the transcriptional activity of AR in prostatic cells. We performed reporter assays in LNCaP cells, AR-positive prostate cancer cells, using the AR-responsive element (ARE)2-TATA-luc, which contains two copies of the AR-binding element sites (30). When LNCaP cells were cotransfected with CRIF1 expression vector and ARE2-TATA-luc in the presence of androgen, CRIF1 significantly suppressed androgen-induced reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner without causing a decrease of AR protein level (Fig. 1A). We observed similar dose-dependent inhibition of AR transactivation by CRIF1 in Cos-7 cells (Fig. 1B) and found that CRIF1 did not affect the basal promoter activity of ARE2-TATA-luc. CRIF1 suppression of AR transactivation was also confirmed with natural AR target promoters, mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter, and PSA promoter. PPC-1 cells, which are AR-negative prostate cancer cells, were cotransfected with AR and CRIF1 expression constructs along with MMTV-luc or PAS-luc reporter. The reporter expression was highly induced by androgen, and CRIF1 coexpression significantly repressed the androgen-induced reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner with both -luc and PAS-luc (Fig. 1, C and D).

Fig. 1.

CRIF1 Represses the Transactivation of AR, which Is Recruited on AR Target Promoters

A, LNCaP cells were cotransfected with pCMV-CRIF1 (100 or 200 ng) and 150 ng ARE2-TATA-luc. Expression levels of AR, CRIF1, and actin were confirmed by Western blot analyses using anti-AR, anti-HA (CRIF1), and anti-β-actin antibodies. B, Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with 100 ng pcDNA3-mAR that expresses a mouse AR, pCMV-CRIF1 (100 or 200 ng), and 150 ng of ARE2-TATA-luc. C and D, PPC-1 cells were cotransfected with 100 ng pcDNA3HA-mAR, pCMV-CRIF1 (50, 100, or 200 ng), and 150 ng of the reporter MMTV-luc (C) or PSA-luc (D). Cells were cultured in media containing 5% charcoal-stripped serum with or without 10 nm DHT for 24 h and were assayed for luciferase activity. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results. All values represent the mean ± sd of duplicate samples. E, LNCaP cells were transfected with pcDNA3HA-CRIF1 and treated with or without 10 nm DHT for 16 h after transfection. Anti-AR and anti-HA antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation. DNAs isolated from the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by PCR using a pair of specific primers spanning the ARE-containing enhancer region of the PSA promoter. A control PCR for nonspecific immunoprecipitation was performed using primers specific to the β-actin coding region. The supernatant (10%, vol/vol) was represented as input chromatin before immunoprecipitation by antibodies.

To determine whether AR and CRIF1 form a complex on an AR target promoter in vivo, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays using LNCaP cells, which were transfected with hemagglutinin (HA)-CRIF1 expression vector (Fig. 1E). In the presence of androgen, both the AR and CRIF1 were associated with the ARE-containing enhancer region of the PSA promoter, whereas none of them was recruited to the region in the absence of androgen (Fig. 1E). This indicates that AR and CRIF1 form a complex with AREs of the PSA promoter in an androgendependent manner, although CRIF1 overexpression remains as a caveat. Taken together, these results suggest that CRIF1 is recruited onto AR target promoters by AR and inhibits androgen-induced transcriptional activity of AR.

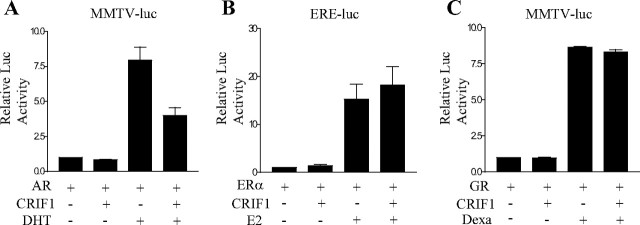

CRIF1-Mediated Repression Is Specific for AR

To investigate whether CRIF1 is able to repress steroid hormone receptors other than AR, we tested estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in Cos-7 cells. In contrast to the strong repression of the androgen-induced transcriptional activity of AR (Fig. 2A), CRIF1 seemed to slightly increase the transcriptional activity of ERα (Fig. 2B). Meanwhile, there was no significant change in the transactivation of GR caused by coexpression of CRIF1 (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results suggest that CRIF1 specifically represses the transcriptional activity of AR.

Fig. 2.

CRIF1 Represses the Transactivation of AR, But Not that of ER or GR

Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with 150 ng of the indicated reporter (MMTV-luc or ERE-luc), 100 ng of the corresponding steroid receptor, and 100 ng of CRIF1 expression construct. Cells were cultured in media containing 5% charcoal-stripped serum, with or without ligand for each receptor, and assayed for luciferase activity after 24 h. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results. All values represent the mean ± sd of duplicate samples. ERE, Estrogen response element; E2, estradiol; Dexa, dexamethasone.

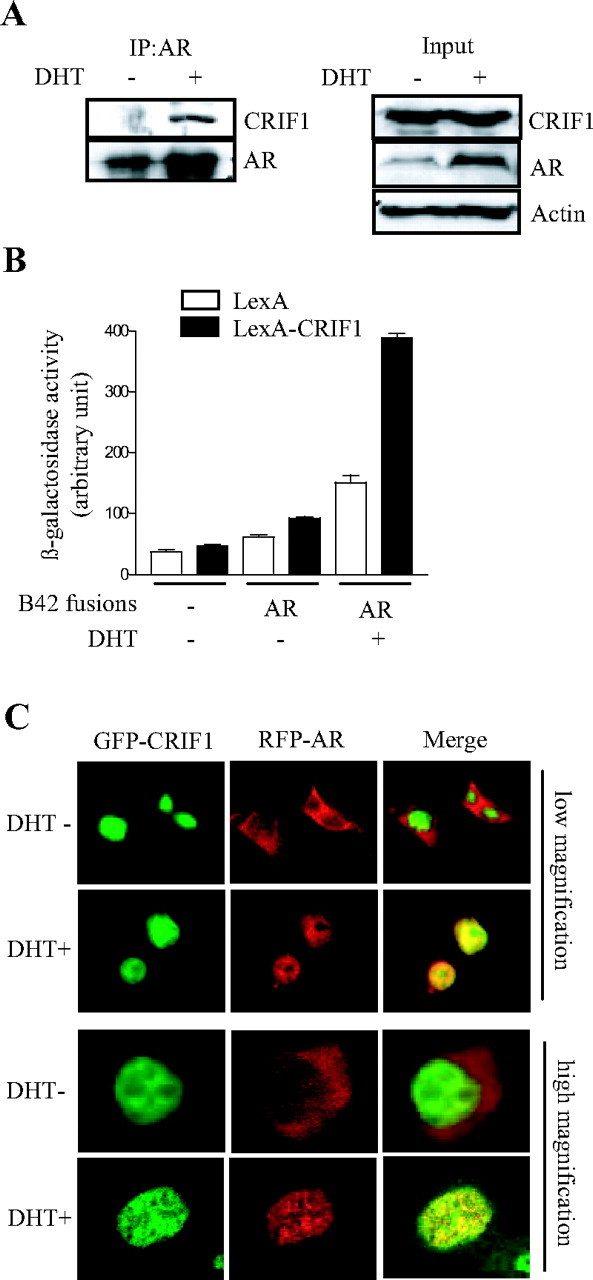

CRIF1 Physically Interacts with AR in Vivo

To determine whether the CRIF1 repression of AR transactivation is mediated by physical interaction, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays using anti-AR antibody and HEK293T cells, which were transfected with AR and CRIF1 expression constructs. As shown in Fig. 3A, CRIF1 was found to associate with AR in an androgen-dependent manner in vivo. To further confirm this interaction, we conducted yeast two-hybrid interaction assays. LexA-fused CRIF1 strongly interacted with the B42-fused AR (Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate that CRIF1 physically interacts with AR in an androgen-dependent manner in vivo.

Fig. 3.

CRIF1 Physically Interacts with AR in an Androgen-Dependent Manner

A, Coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed using HEK293T cells cotransfected with pcDNA3-mAR and pcDNA3HA-CRIF1 constructs. Cells were treated with or without 10 nm DHT for 12 h. Coimmunoprecipitations were performed with anti-AR antibody, and Western blot analyses were carried out using anti-CRIF1 and anti-AR antibodies. Expression levels of CRIF, AR, and actin were confirmed by Western blot analyses of inputs. B, Yeast two-hybrid interaction assays were conducted with LexA-DBD or LexA-CRIF1 and B42-AR in the EGY48 yeast strain in the absence or presence of DHT. C, HEK293T cells were transfected with GFP-CRIF1 and RFP-AR constructs in the absence or presence of DHT. The localization of CRIF1 and AR was detected by green and red fluorescence, respectively. Colocalization is demonstrated by a yellow signal, generated by the overlay of red and green signals. IP, Immunoprecipitation.

To determine whether CRIF1 colocalizes with AR in cells, we performed confocal microscopic analyses of HEK293T cells that were cotransfected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged CRIF1 and red fluorescent protein (RFP)-tagged AR. CRIF1 was detected in the nucleus in the absence and the presence of androgen (Fig. 3C). However, AR translocated into the nucleus only in the presence of ligand, colocalizing with CRIF1 (Fig. 3C). Moreover, AR and CRIF1 were colocalized to the same subnuclear foci (Fig. 3C, high magnification). Taken together, these results demonstrate that CRIF1 physically interacts and is colocalized with AR in an androgen-dependent manner.

Determination of Interaction Domains within CRIF1 and AR

To map the AR domains required for interaction with CRIF1, we employed a number of AR deletion constructs in yeast two-hybrid interaction assays (Fig. 4A). The region containing AF1 and DBDh domains of AR (B42-AR-AF1+DBDh) interacted with CRIF1 fused to LexA, whereas the DBDh or LBD domain of AR showed no significant interaction with CRIF1 (Fig. 4B), which indicates that the AF-1 domain of AR is required for interaction with CRIF1. To confirm this interaction domain of AR, we performed glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pull-down assays using in vitro translated [35S]methionine-labeled CRIF1 and bacterially expressed GST-fused AR deletion mutants. CRIF1 interacted with GST-AR AF-1+DBDh, but not with GST only, GST-AR DBDh, or GST-AR LBD (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results suggest that the AF-1 domain of AR is responsible for the interaction of AR with CRIF1.

Fig. 4.

Mapping of Interaction Domains within AR and CRIF1

A, The schematic representations of the full-length AR and its deletion constructs used in yeast two-hybrid interaction and GST pull-down assays. B, Yeast two-hybrid interaction assays were performed with LexA-CRIF1 and B42-AR deletion mutants in the EGY48 yeast strain. C, In GST pull-down assays, CRIF1 labeled with [35S]methionine by in vitro translation was incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads containing bacterially expressed GST alone or GST-AR deletion mutant fusion proteins. The input lane represents 10% of the total volume used in the binding assay. D, The schematic representations of the full-length CRIF1 and its deletion mutant constructs used in yeast two-hybrid interaction and transient transfection assays. E, Yeast two-hybrid interaction assays were performed with LexA-CRIF1 deletion mutants and B42-AR in the EGY48 yeast strain. F, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with 100 ng pcDNA3-mAR, 150 ng ARE2-TATA-luc, and pCMV-CRIF1 full-length or deletion mutant constructs (100 or 200 ng). Cells were treated with or without 10 nm DHT and assayed for luciferase activity after 24 h. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results. All values represent the mean ± sd of duplicate samples. Wt, Wild type; C-C, coiled-coil domain.

The domain within CRIF1 that is required for interaction with AR was also accessed by yeast two-hybrid interaction assays using CRIF1 deletion mutant constructs (Fig. 4D). As shown in Fig. 4E, both LexA-CRIF1 N-terminal half and LexA-CRIF1 C-terminal half seemed to interact with B42-AR. Moreover, the CRIF1 N- and C-terminal half repressed the transactivation of AR, as well as the full-length CRIF1 (Fig. 4F). These results suggest that the N-terminal and C-terminal half regions of CRIF1 are capable of independently interacting with AR, thereby repressing the transactivation of AR.

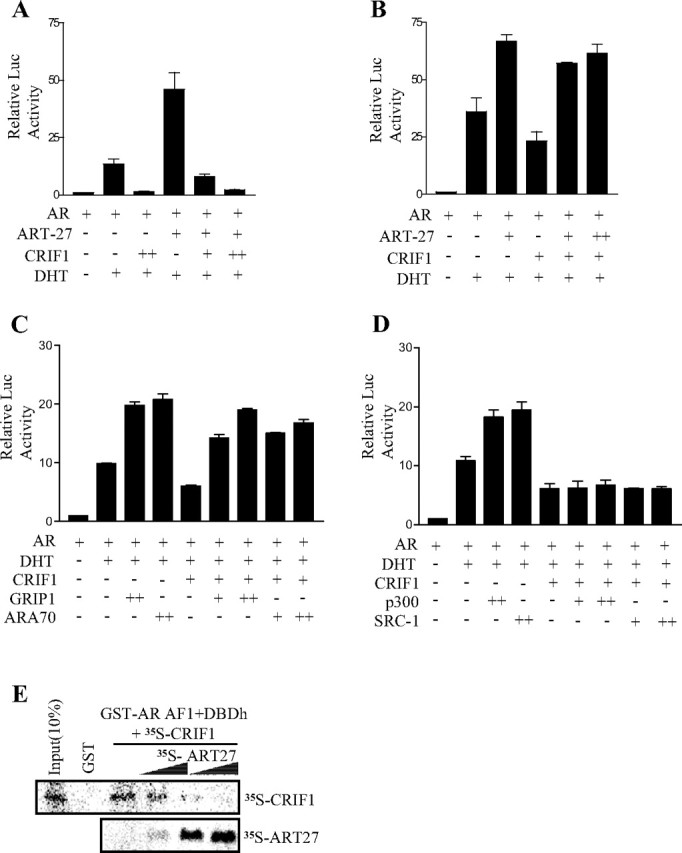

CRIF1 Inhibits AR Transactivation through Competition with Coactivators

It was previously reported that CRIF1 inhibited the transcriptional activity of Nur77 by competing with the coactivator SRC-2 [GR-interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) (2)]. Moreover, CRIF1 interacted with AR through the AR AF-1 domain (Fig. 4, B and C), which interacts with a number of coactivators. Thus, we tested whether CRIF1 regulates the coactivator-enhanced transcriptional activity of AR in HEK293T cells. Overexpression of AR trapped clone-27 (ART-27), one of the AR coactivators that bind to the AR AF-1 domain, enhanced the androgen-induced transcriptional activity of AR by approximately 3-fold, and CRIF1 coexpression significantly decreased the ART-27-enhanced transcriptional activity of AR in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). In addition, the CRIF1-mediated repression of AR transactivation was recovered by overexpression of ART-27 (Fig. 5B). We also tested other AR coactivators for their competition with CRIF1. Overexpressions of GRIP1 and ARA70 recovered the repression by CRIF1, but overexpression of p300 or SRC-1 did not have the same effect (Fig. 5, C and D).

Fig. 5.

CRIF1 Represses AR Transactivation by Competition with AR Coactivators for Binding to AR

A and B, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with 150 ng ARE2-TATA-luc reporter, 100 ng pcDNA3-mAR, pcDNA3HA-ART-27 (100 or 200 ng), and pCMV-CRIF (100 or 200 ng). C and D, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with 150 ng ARE2-TATA-luc, 100 ng pcDNA3-mAR, 100 ng pcDNA3HA-CRIF1, and coactivators (100 or 300 ng). Cells were treated with or without DHT for 24 h and were then assayed for luciferase activity. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results. All values represent the mean ± sd of duplicate samples. E, ART27 interferes in the interaction between AR and CRIF1. [35S]methionine-labeled CRIF1 was incubated with bead-bound GST-AR AF1+DBDh fusion protein in the presence of increasing amounts of in vitro-translated ART-27. Input represents 10% of the total volume of 35S-labeled CRIF1 used in the assay.

To determine whether CRIF1 physically competes with ART-27 for AR binding, we conducted GST pull-down competition assays using GST-AR AF1+DBDh and in vitro translated [35S]methionine-labeled CRIF1 and ART-27 proteins. CRIF1 interacted with GST-AR AF1+DBDh, and their interaction was impeded by ART-27 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5E). Taken together, these results demonstrate that CRIF1 inhibits the transcriptional activity of AR by outcompeting some of the AR coactivators in binding with AR.

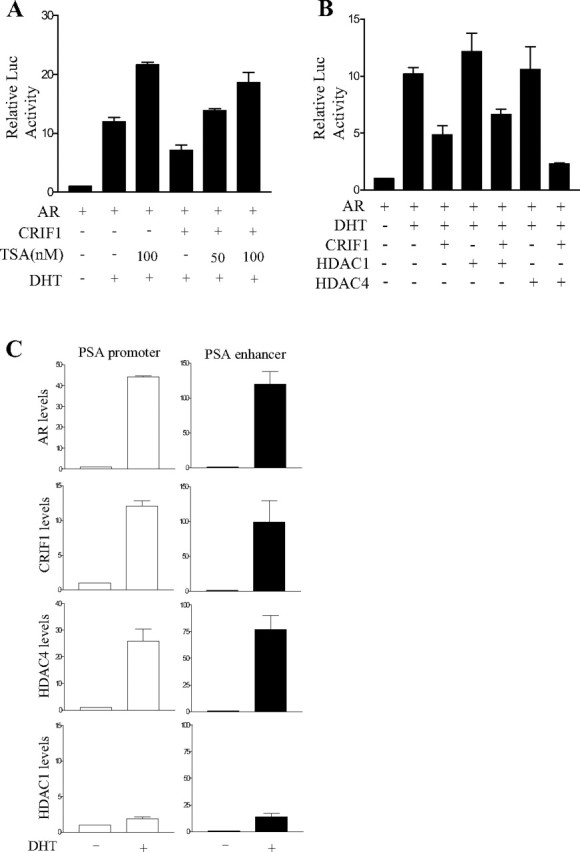

HDAC4 Is Involved in the CRIF1-Mediated Repression of AR Transactivation

The repression of AR transactivation by some corepressors involves HDAC activities (31, 32). Thus, we tested the involvement of HDACs in the CRIF1-mediated repression of AR transactivation using an HDAC inhibitor, trichostatin A (TSA). The repression of AR transactivation by CRIF1 was significantly recovered by treatment with TSA (Fig. 6A), which suggests the involvement of HDAC in this repression. To further confirm the involvement of HDAC, HDACs were overexpressed with CRIF1 in PPC-1 cells, and their effects were subsequently examined. As shown in Fig. 6B, the repression of AR transactivation by CRIF1 was further suppressed by the overexpression of HDAC4, but not by that of HDAC1. Overexpression of HDAC1 or HDAC4 itself showed only a slight effect on AR transactivation in the presence of androgen.

Fig. 6.

Involvement of HDAC in the CRIF1 Repression of AR Transactivation

A, PPC-1 cells were cotransfected with 150 ng ARE2-TATA-luc, 100 ng pcDNA3-mAR, and 100 ng pCMV-CRIF1. Cells were treated with or without 50 nm or 100 nm of TSA in the presence or absence of 10 nm DHT. B, PPC-1 cells were cotransfected with 150 ng ARE2-TATA-luc, 100 ng pcDNA3-mAR, 100 ng pCMV-CRIF1, and 400 ng HDAC1 or HDAC4 expression plasmid. Cells were treated with or without 10 nm DHT. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results. All values represent the mean ± sd of duplicate samples. C, LNCaP cells were transfected with pcDNA3HA-CRIF1, pcDNA3-HDAC1, and pcDNA3Flag-HDAC4 and treated with or without 10 nm DHT for 6 h after transfection. Anti-AR, anti-HA, anti-HDAC1, and anti-Flag antibodies were used for immunoprecipitations. DNAs isolated from the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by real-time PCR using a pair of specific primers spanning the region containing AREs of the PSA proximal promoter and enhancer. A control PCR for nonspecific immunoprecipitation was performed using primers specific to the β-actin coding region. The level of each protein recruited in the PSA proximal promoter or enhancer region was normalized to that in the actin region. The level in the absence of DHT was defined as 1.0.

To investigate that HDAC4 is recruited with CRIF1 at the AREs of the PSA proximal promoter and enhancer, we performed ChIP assays using LNCaP cells, which were transfected with HA-CRIF1, HDAC1, and Flag-HDAC4 expression vectors. We also checked androgen-induced increase of each protein level on the PSA proximal promoter and enhancer by real-time PCR. AR and CRIF1 were highly associated with both of the PSA proximal promoter and enhancer in the presence of dihydrotestosterone (DHT), although their levels were increased much more on the PSA enhancer than on the proximal promoter by DHT treatment (Fig. 6C). HDAC4 showed a similar androgen-dependent association to ARE-containing regions of the PSA promoter with AR and CRIF1. However, the levels of HDAC1 on the PSA promoter were very low compared with HDAC4 levels although its level was increased to a certain extent on the PSA enhancer region by DHT treatment (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these results suggest that HDAC4 is involved in the CRIF1-mediated repression of AR transactivation.

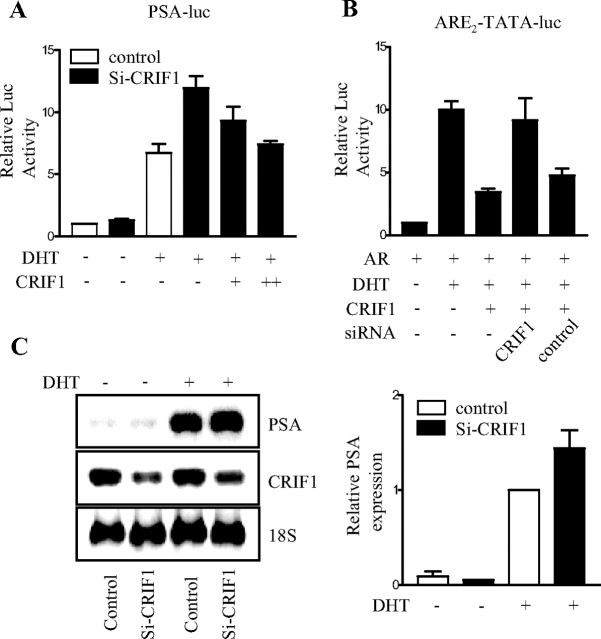

Effects of CRIF1 Knockdown on the Transactivation and Target Gene Expression of AR

To confirm the role of CRIF1 in the modulation of AR transactivation, we examined the effect of endogenous CRIF1 knockdown using siRNA. CRIF1 is expressed in the rat prostate and in androgen-independent and androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 7A, the androgen-induced transactivation of AR was increased by the down-regulation of endogenously expressed CRIF1 with CRIF1 siRNA (si-CRIF1) (Fig. 7C) when tested with PSA-luc reporter in LNCaP cells, which was rescued by the overexpression of CRIF1 (Fig. 7A). Moreover, siRNA-mediated knockdown of CRIF1 also caused the recovery of AR transactivation that had been repressed by CRIF1 overexpression, whereas the control siRNA, a scrambled siRNA, showed little effect (Fig. 7B). We also examined the role of endogenous CRIF1 on the expression of an endogenous AR target gene, PSA, using si-CRIF1 in LNCaP cells. The mRNA level of PSA was increased to a certain extent by down-regulation of CRIF1 with si-CRIF1 in the presence of androgen (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these results suggest that the level of endogenous CRIF1 controls the expression of AR target genes by modulating the transactivation of AR.

Fig. 7.

Effects of CRIF1 Knockdown on AR Transactivation and the Expression of the AR Target Gene

A and B, Knockdown of the endogenous or exogenous CRIF1 by CRIF1 siRNA increases the transactivation of AR. A, LNCaP cells were transfected with 150 ng PSA-luc and control or CRIF1 siRNA. After 48 h of siRNA transfection, si-CRIF1-transfected cells were again transfected with pCMV-CRIF1. B, Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with 100 ng pcDNA3-mAR, 100 ng pCMV-CRIF1, 150 ng ARE2-TATA-luc, and control or CRIF1 siRNA. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results. All values represent the mean ± sd of duplicate samples. C, Knockdown of the endogenous CRIF1 by CRIF1 siRNA increases the mRNA levels of endogenous PSA in LNCaP cells. LNCaP cells were transfected with control or CRIF1 siRNA in the absence or presence of DHT. The mRNA levels of PSA and CRIF1 were determined by Northern blot analysis and quantified using a phosphor imager. rRNA (18S) was used as an internal control. PSA expression levels were normalized to the 18S rRNA levels. The data are representative of at least two independent experiments. All values represent the mean ± sd of duplicate samples.

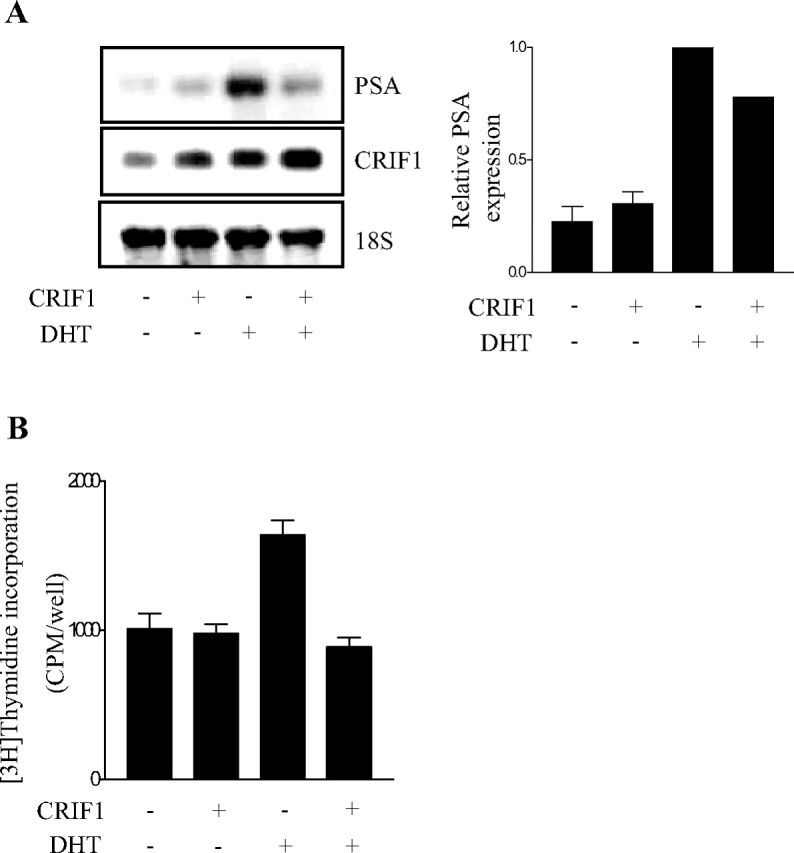

Overexpression of CRIF1 Decreases the Expression of an Endogenous AR Target Gene and Blocks the Proliferation and Cell Cycle Progression of Prostate Cancer Cells

To confirm that a higher expression level of CRIF1 further represses the expression of the AR target gene, we performed Northern blot analysis of the endogenous mRNA level of PSA in LNCaP cells by overexpressing CRIF1. Overexpression of CRIF1 by transient transfection significantly decreased the androgen-induced mRNA level of PSA in LNCaP cells as expected (Fig. 8A). Meanwhile, CRIF1 overexpression itself slightly increased the mRNA level of PSA in the absence of DHT.

Fig. 8.

Effects of CRIF1 Overexpression on the Expression of the AR Target Gene and the Proliferation of Prostate Cancer Cells

A, Overexpression of CRIF1 decreases the endogenous PSA mRNA level. LNCaP cells were transfected with or without pCMV-CRIF1 in the absence or presence of 10 nm DHT. The mRNA levels of PSA and CRIF1 were determined by Northern blot analysis and quantified using a phosphor imager. rRNA (18S) was used as an internal control. PSA expression levels were normalized to the 18S rRNA levels. The data are representative of at least two independent experiments. All values represent the mean ± sd of duplicate samples. B, Overexpression of CRIF1 inhibits androgen-induced proliferation of LNCaP cells. LNCaP cells were transfected with or without pCMV-CRIF1 in the absence or presence of 0.1 nm DHT for 72 h. Cell proliferation was determined by the incorporation of [3H]thymidine during the last 4 h of the culture. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments. All values represent the mean ± sd of triplicate samples.

To investigate the effect of CRIF1 expression on the proliferation of androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells, LNCaP cells were transiently transfected with CRIF1 expression construct, and cell proliferation was subsequently measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation assays. Overexpression of CRIF1 significantly decreased the rate of androgen-induced DNA synthesis, although it did not affect the DNA synthesis rate in the absence of androgen (Fig. 8B).

To address the effect of CRIF1 expression on the cell cycle progression of androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells, we performed flow cytometric analysis with LNCaP cells, which were transfected with HA-CRIF1 expression vector (Table 1). In the absence of DHT, overexpression of CRIF1 slightly decreased cell populations in the S and G2/M phase compared with control cells. The DHT treatment of LNCaP cells itself enhanced cell cycle progression as previously reported (33), increasing significantly the size of S and G2/M-phase populations. In the presence of DHT, cells overexpressed with CRIF1 showed much less in the S and G2/M phase than control cells. Thus, overexpression of CRIF1 caused more cells to arrest at the G0-G1 phase in the presence of DHT (increased from 70.7–81.3%) than in the absence of DHT (increased from 75.2–77.1%). Taken together, these results suggest that CRIF1 inhibits the expression of AR target genes and also blocks the proliferation and cell cycle progression of androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells in an androgen-dependent manner.

Table 1.

Effects of CRIF1 Overexpression on the Cell Cycle Progression of Prostate Cancer Cells

| Cell Cycle Distribution (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0–G1 | S | G2 + M | |||

| DHT(−)/empty vector | 75.2% | 23.1% | 1.7% | ||

| DHT(−)/CRIF1 | 77.1% | 22.1% | 0.8% | ||

| DHT(+)/empty vector | 70.7% | 26.2% | 3.1% | ||

| DHT(+)/CRIF1 | 81.3% | 18.7% | 0% | ||

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that CRIF1 represses the transactivation of AR and the androgen-dependent proliferation of LNCaP cells. CRIF1 directly interacts with AR and inhibits AR-mediated transactivation of the PSA gene by competing for the binding of AR with AR coactivators and/or by recruiting HDAC. Moreover, the knockdown of the endogenous CRIF1 gene increases AR transactivation and PSA mRNA levels in an androgen-dependent manner. Current observations suggest that CRIF1 may play a physiological role in AR-positive prostate cancer cells.

CRIF1 itself plays a role as a negative regulator of cell proliferation by inhibiting Cdk1 and Cdk2 in NIH3T3 cells (1). Moreover, CRIF1 inhibits the progression of the cell cycle though the repression of the Nur77 function in thyroid cells (2). Here, we show that CRIF1 also inhibits androgen-induced proliferation and cell cycle progression of prostate cancer cells through the repression of AR function (Fig. 8B and Table 1). These data suggest that CRIF1 is able to modulate the proliferation of various kinds of cells, and that these modulations may result from the cross talk between CRIF1 and other proteins that regulate cell proliferation in a cell type-specific manner. Moreover, the CRIF1 gene is differentially expressed in normal and cancer tissues and is expressed in epithelial cancer cells of the thyroid and breast tissues at a lower level than in adjacent epithelial normal cells (1), which supports the hypothesis that CRIF1 plays a role in the regulation of cell proliferation. Therefore, investigation of CRIF1 expression and function in prostate cancers would be therapeutically meaningful because an increase of CRIF1 expression occurring by any means may inhibit the proliferation of prostate cancer cells by repressing the function of AR.

It has recently been reported that AR is phosphorylated and stabilized by Cdk1 (Cdc2), resulting in an elevated AR protein level in the cell (34). Because CRIF1 inhibits the kinase activity of Cdc2-cyclin B1 and Cdk2-cyclin E (1), the CRIF1 may indirectly affect the function of AR in the cell by inhibiting Cdk1 activity and subsequent AR phosphorylation. Further studies are needed to determine whether Cdk1 is also involved in the CRIF1-mediated repression of AR transactivation, although we detected no decrease of the AR protein level resulting from CRIF1 expression in prostate cancer cells (Fig. 1A, lower panel).

CRIF1 represses the transactivation of AR, whereas it enhances the transactivation of ERα (Fig. 2). Cyclin D1 has been reported to act similarly, inhibiting the transcriptional activity of AR in a ligand-dependent manner (35) and activating the transcriptional activity of ER in a ligand-independent manner (36). In addition, coactivators such as p300 and p300/cAMP response element binding (CREB)-binding protein-associated factor rescue cyclin D1-mediated repression of AR transactivation, which suggests that cyclin D1, like CRIF1, inhibits the transcriptional activity of AR by competing with AR coactivators (35). Meanwhile, cyclin D1 enhances the transcriptional activity of ER through the recruitment of SRC-1 (36), as opposed to that for AR transactivation. Cyclin D1, and probably CRIF1, seem to associate with specific coregulators depending on its binding partner, which may be AR or ER. Regarding steroid hormone receptors, the roles of cyclin D1 as a coregulator may be similar to those of CRIF1. It would be worthwhile to investigate whether CRIF1 and cyclin D1 have different functions between prostate cancers and breast cancers in which AR and ER, respectively, play a crucial role in cell proliferation.

AR transactivation is enhanced by many coactivators, including ART-27, p300, SRC-1, GRIP1, and ARA70 (37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44). The CRIF1 repression of AR transactivation, however, is recovered by the overexpressions of ART-27, GRIP1, and ARA70, but not by p300 and SRC-1 (Fig. 5), which suggests that CRIF1 only competes with specific AR coactivators. The use of the same AR-interacting region by AR coactivators and CRIF1 might be one reason for the coactivator specificity of the competition between CRIF1 and AR coactivators. However, ARA70 that interacts with AR though the AR DBDs and LBDs is still able to recover in terms of the repression of AR transactivation by CRIF that interacts with AR through the AR AF-1 region. The overall structure and other components of the AR complex might be important for the determination of coactivator specificity. CRIF1 also inhibits Nur77 transactivation in a similar manner, through its competition with Nur77 coactivators, but unlike the CRIF1-mediated AR repression, which involves the recruitment of HDAC4, HDAC is not involved in the repression (2). This suggests that the repression mechanism of CRIF1 may differ according to the interaction partner of CRIF1 or the cell type in which CRIF1 functions.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that CRIF1 represses AR transactivation by direct interaction and also inhibits AR-induced endogenous target gene expression. Here, we propose that CRIF1 is a novel corepressor of AR, and that the inappropriate regulation of CRIF1 gene expression may be involved in the development of prostate cancers through the alteration of AR transactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

The mammalian expression vectors of pcDNA3-mouse AR, GR, -GRIP1, -SRC-1, -p300, and -ARA70 have been described previously (45, 46). The mammalian expression vectors of HDAC1 and HDAC4, pARE2-TATA-luc reporter, MMTV-luc reporter, PSA-luc reporter, and B42-mAR plasmid were also described previously (31). The mammalian expression vector of pcDNA3-ERα, and ERE-luc reporter plasmid were kindly provided as gifts from J. W. Lee (Baylor College of Medicine) (47). The expression vectors of pCMV-CRIF1, pCDNA3HA-CRIF1, pEGFP-CRIF1, pCMV-CRIF1 (1–98), pCMV-CRIF1 (99–222), and LexA-CRIF1 were described previously (1, 2).

The LexA-fused CRIF1 deletion mutants were constructed by cloning BamHI-XhoI fragments of pCMV-CRIF1(1–98) and -CRIF1(99–222) into the LexA vector. ART-27 construct was cloned into the EcoRI-XhoI digested pcDNA3HA vector. pRFP-AR was constructed by cloning the XhoI-BamHI fragment of pEGFP-AR into the pHcRed1c-1 vector. The B42-AR and GST-AR deletion mutants were generated by cloning the regions spanning AF1+DBDh, DBDh, and LBD of mouse AR into vector B42 digested with EcoRI and XhoI restriction enzymes.

The CRIF1-siRNA and control-siRNA construct was described previously (1, 2).

Cell Culture and Transient Transfection Assays

Cos-7, PPC-1, and HEK293T cell lines were maintained in DMEM (Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The LNCaP cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CRL-1740) and maintained in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Inc.) supplemented with l-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were plated in 24-well plates and transfected with the indicated amount of expression plasmids, a reporter plasmid, and the control lacZ expression plasmid pCMV-β (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, CA), by using Superfect or Effectene reagent (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Total amounts of expression vectors were kept constant by the addition of appropriate amounts of empty pcDNA3 vector. Cells kept in 5% charcoal-stripped serum were treated with 10 nm DHT for 24 h after transfection. TSA was treated 20 h before harvesting. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were assayed as described previously (48). The levels of luciferase activity were normalized to lacZ expression.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay and Real-time PCR

LNCaP cells were transfected with pcDNA3HA-CRIF1, pcDNA3HDAC1, and pcDNA3Flag-HDAC4 expression plasmids, treated or not treated with 10 nm DHT for 6 or16 h after 24 h of transfection, and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde. After incubating the samples with TSE I [100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 9.4) and 10 mm dithiothreitol] for 20 min at 30 C, the cells were washed and processed for ChIP assays as described previously (48). Supernatant (10%, vol/vol) was saved as input chromatin before immunoprecipitation. Anti-AR, anti-HA, anti-HDAC1, and anti-Flag antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) were used for immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitated DNA and input-sheared DNA were subjected to PCR or real-time PCR using a PSA proximal promoter primer pair (forward, 5′-ACAATCTCCTGAGTGCTGGTGT-3′; and reverse, 5′-GCAGAGGAGACATGCCCAG-3′) or PSA enhancer primer pair (forward, 5′-TGAGAAACCTGAGATTAGGA-3′; and reverse, 5′-ATCTCTCTCAGATCCAGGCT-3′), which amplify regions spanning the ARE. As a control, PCRs were performed using an actin primer pair (sense, 5′-GAGACCTTCAACACCCCAGCC-3′; and antisense, 5′-CCGTCAGGCAGCTCATAGCTC-3′), which amplify a region spanning exon 4 of the β-actin gene.

Real-time PCR was performed as described previously (46), using a real-time PCR machine (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia) and QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s procedure. Signals were analyzed with the Rotor Gene 2000 (RG-2000) software (Corbett Research).

Coimmunoprecipitation and Western Blot Assays

Coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed with HEK293T cells that were transfected with 1 μg AR and 1 μg CRIF1 expression plasmids. Cells were treated with or without 10 nm DHT for 12 h after transfection and were harvested in RIPA cell lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 50 mm NaCl; 2.5 mm EGTA; 1% Triton X-100; 50 mm NaF; 10 mm Na4P2O7; 10 mm Na3VO4; 1 μg/ml aprotinin; 0.1 μg/ml leupeptin; 1 μg/ml pepstatin; 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; and 1 mm dithiothreitol). Whole-cell lysate (400 μg) was incubated with 2 μg anti-AR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 4 h at 4 C and was further incubated for another 4 h after the addition of 20 μl of protein A-agarose bead slurry (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Agarose beads were washed three times with RIPA buffer at 4 C, and bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins on the gels were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Sigma), subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-CRIF1 (1), anti-AR, anti-HA, and anti-β-actin antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and then detected with an ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

Yeast Two-Hybrid and Liquid β-gal Assays

Yeast two-hybrid interaction assays were performed as described previously (31). In brief, plasmids for LexA-DBD fused to the full-length CRIF1 or the deletion mutants of CRIF1, and plasmids for B42-AD or B42-AD fused to the full-length AR or to the domain mutant of AR were cotransformed into yeast strain EGY48 cells. The transformants were selected on plates (Ura-, His-, and Trp-) with appropriate selection markers and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. The liquid β-galactosidase assay was carried out as described previously (31).

GST Pull-Down Assay

GST and GST-AR domain mutant fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells and isolated with glutathione-Sepharose-4B beads (Pharmacia Biotech). Immobilized GST fusion proteins were then incubated with [35S]methionine-labeled CRIF1 protein produced by in vitro translation using the TNT-coupled transcription-translation system (Promega Corp, Madison, WI). The binding reactions were carried out in 250 μl of GST binding buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.9; 100 mm NaCl; 10% glycerol; 0.05% Nonidet P-40; 5 mm MgCl2; 0.5 mm EDTA; 1 mm dithiothreitol; and 1.5% BSA) for 4 h at 4 C. The beads were washed three times with 1 ml GST binding buffer. Bound proteins were eluted by the addition of 20 μl sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer and were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

For in vitro competition assays, [35S]methionine-labeled ART-27 protein produced by in vitro translation was added to the binding reaction, and beads were washed three times with the binding buffer, resuspended in 2× SDS loading buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized using a phosphor imager (BAS-1500; Fuji, Stamford, CT). The GST-fused proteins used in each reaction were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and quantified by Coomassie blue staining. Of the in vitro translated CRIF1 and ART-27 used in each reaction, 10% was loaded in the input lanes of the gels.

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy

On the day before transfection, HEK293T cells were plated onto gelatin-coated coverslips. GFP-CRIF1 and RFP-AR were transiently transfected using Superfect reagent (QIAGEN). The cells were treated with or without 10 nm DHT and incubated for an additional 24 h. Cells were then washed three times with cold PBS and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. Fixed cells were mounted on glass slides and observed under a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus Corp., Lake Success, NY).

siRNA Experiment

The siRNAs for CRIF1 were prepared as described previously (1, 2). In brief, the siRNAs for CRIF1 (Fig. 7) were chemically synthesized (Samchully Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea), deprotected, annealed, and transfected according to the instructions of the manufacturer. LNCaP cells and Cos-7 cells were transfected with siRNA using Oligofectamine reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

Northern Blot Analysis

Total RNA was isolated using TRI Reagent (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Total RNA (20 μg) was fractionated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel containing formaldehyde and transferred to nylon membranes (Zeta-probe, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Richmond, CA) by capillary blotting with 10× sodium citrate-sodium chloride (SSC). After UV cross-linking and prehybridization, membranes were hybridized overnight at 42 C in a solution containing 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 5× SSC, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mg/ml denatured salmon sperm DNA, and a total of 2–4 × 106 cpm of 32P-labeled probes. After hybridization, membranes were washed twice for 5 min at room temperature in 2× SSC and 0.1% SDS, followed by washing for 30 min at 65 C in 0.5× SSC and 0.1% SDS. Membranes were then exposed using Kodak RX films (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY) for 12–24 h at −70 C. The signals were normalized to the 18S rRNA internal control.

Thymidine Incorporation

LNCaP cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and were transfected with or without CRIF1 expression plasmid. After 24 h of transfection, the cells were treated with or without 0.1 nm DHT for 72 h and were then pulse labeled with [3H]thymidine (10 μCi/ml; specific activity 80 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Norwalk, CT) for 4 h. Cells were harvested onto a glass microfiber filter (Whatman, Inc., Florham Park, NJ) and intensively washed with distilled water. The incorporation of thymidine into DNA was measured by counting the filters with a scintillation counter.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

LNCaP cells were transfected with or without CRIF1 expression plasmid. After 24 h of transfection, the cells were treated with or without 0.1 nm DHT for 72 h. Samples were prepared for flow cytometric analysis essentially as described previously (1). In brief, cells were washed with 1× PBS and then fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol. Samples were then washed with 1× PBS and stained with 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma) containing 100 μg/ml ribonuclease (Sigma) for 1 h at 37 C. Cell cycle analysis was performed using a Coulter Epics XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA) and System II software (Beckman Coulter). At least 10,000 cells were analyzed per sample.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. W. Lee for expression vectors and reporter plasmids, and Dr. J. H. Cho for helpful discussion and suggestions.

NURSA Molecule Pages:

Coregulators: ARA70 | ART-27 | CRIF1 | GRIP1 | HDAC1 | HDAC4;

Ligands: Dihydrotestosterone;

Nuclear Receptors: AR.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grant R01-2006-000-10378-0 from the Basic Research Program of the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online September 20, 2007

Abbreviations: AF-1, Activation function-1; AR, androgen receptor; ARE, androgen response element; ART-27, AR trapped clone-27; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CRIF1, CR6-interacting factor 1; DBD, DNA-binding domain; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; ER, estrogen receptor; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; GRIP, GR-interacting protein; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; HA, hemagglutinin; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HEK 293T, human embryonic kidney-93T; LBD, ligand-binding domain; MMTV, mouse mammary tumor virus; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RFP, red fluorescent protein; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; si-CRIF1, CRIF1 siRNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SRC, steroid receptor coactivator; SSC, sodium citrate-sodium chloride; TSA, trichostatin A.

References

- 1.Chung HK, Yi YW, Jung NC, Kim D, Suh JM, Kim H, Park KC, Song JH, Kim DW, Hwang ES, Yoon SH, Bae YS, Kim JM, Bae I, Shong M 2003. CR6-interacting factor 1 interacts with Gadd45 family proteins and modulates the cell cycle. J Biol Chem 278:28079–28088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park KC, Song KH, Chung HK, Kim H, Kim DW, Song JH, Hwang ES, Jung HS, Park SH, Bae I, Lee IK, Choi HS, Shong M 2005. CR6-interacting factor 1 interacts with orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 and inhibits its transactivation. Mol Endocrinol 19:12–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oh NS, Yoon SH, Lee WK, Choi JY, Min DS, Bae YS 2007. Phosphorylation of CKBBP2/CRIF1 by protein kinase CKII promotes cell proliferation. Gene 386:147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelmann EP 2002. Molecular biology of the androgen receptor. J Clin Oncol 20:3001–3015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunha GR, Donjacour AA, Cooke PS, Mee S, Bigsby RM, Higgins SJ, Sugimura Y 1987. The endocrinology and developmental biology of the prostate. Endocr Rev 8:338–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasnitzki I, Mizuno T 1980. Prostatic induction: interaction of epithelium and mesenchyme from normal wild-type mice and androgen-insensitive mice with testicular feminization. J Endocrinol 85:423–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeh S, Tsai MY, Xu Q, Mu XM, Lardy H, Huang KE, Lin H, Yeh SD, Altuwaijri S, Zhou X, Xing L, Boyce BF, Hung MC, Zhang S, Gan L, Chang C 2002. Generation and characterization of androgen receptor knockout (ARKO) mice: an in vivo model for the study of androgen functions in selective tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:13498–13503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donjacour AA, Cunha GR 1998. The effect of androgen deprivation on branching morphogenesis in the mouse prostate. Dev Biol 128:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinlein CA, Chang C 2004. Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr Rev 25:276–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadi MV, Walsh PC, Barrack ER 1991. Immunohistochemical study of androgen receptors in metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer 67:3057–3064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chodak GW, Kranc DM, Puy LA, Takeda H, Johnson K, Chang C 1992. Nuclear localization of androgen receptor in heterogeneous samples of normal, hyperplastic and neoplastic human prostate. J Urol 147:798–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Winter JAR, Janssen PJA, Sleddens HMEB, Verleun-Mooijman MCT, Trapman J Brinkmann AO, Santerse AB, Schroeder FH, van der Kwast TH 1994. Androgen receptor status in localized and locally progressive hormone refractory human prostate cancer. Am J Pathol 144:735–746 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao J, Isaacs JT 1998. Development of an androgen receptor-null model for identifying the initiation site for androgen stimulation of proliferation and suppression of programmed (apoptotic) death of PC-82 human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res 58:3299–3306 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zegarra-Moro OL, Schmidt LJ, Huang H, Tindall DJ 2002. Disruption of androgen receptor function inhibits proliferation of androgen-refractory prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res 62:1008–1013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haag P, Bektic J, Bartsch G, Klocker H, Eder IE 2005. Androgen receptor down regulation by small interference RNA induces cell growth inhibition in androgen sensitive as well as in androgen independent prostate cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 96:251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao X, Tang S, Thrasher JB, Griebling TL, Li B 2005. Small-interfering RNA-induced androgen receptor silencing leads to apoptotic cell death in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 4:505–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW 1994. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem 63:451–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langley E, Zhou ZX, Wilson EM 1995. Evidence for an anti-parallel orientation of the ligand-activated human androgen receptor dimer. J Biol Chem 270:29983–29990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong CI, Zhou ZX, Sar M, Wilson EM 1993. Steroid requirement for androgen receptor dimerization and DNA Binding: modulation by intramolecular interactions between the NH2-terminal and steroid-binding domains. J Biol Chem 268:19004–19012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Truss M, Bartsch J, Schelbert A, Hache RJ, Beato M 1995. Hormone induces binding of receptors and transcription factors to a rearranged nucleosome on the MMTV promoter in vivo. EMBO J 14:1737–1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T 1996. The CBP co-activator is a histone acetyltransferase. Nature 384:641–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogryzko VV, Schiltz RL, Russanova V, Howard BH, Nakatani Y 1996. The transcriptional coactivators p300 and CBP are histone acetyltransferases. Cell 87:953–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imhof A, Yang X-J, Ogryzko VV, Nakatani Y, Wolffe AP, Ge H 1997. Acetylation of general transcription factors by histone acetyltransferases. Curr Biol 7:689–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinzel T, Lavinsky RM, Mullen TM, Soderstrom M, Laherty CD, Torchia J, Yang WM, Brard G, Ngo SD, Davie JR, Seto E, Eisenman RN, Rose DW, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. 1997. A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature 387:43–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagy L, Kao HY, Chakravarti D, Lin RJ, Hassig CA, Ayer DE, Schreiber SL, Evans RM 1997. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase. Cell 89:373–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gobinet J, Auzou G, Nicolas JC, Sultan C, Jalaguier S 2001. Characterization of the interaction between androgen receptor and a new transcriptional inhibitor, SHP. Biochemistry 40:15369–15377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loy CJ, Sim KS, Young EL 2003. Filamin-A fragment localizes to the nucleus to regulate androgen receptor and coactivator functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:4562–4567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Yang Y, Yeh S, Chang C 2004. ARA67/PAT1 functions as a repressor to suppress androgen receptor transactivation. Mol Cell Biol 24:1044–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dedhar S, Rennie PS, Shago M, Hagesteijn CY, Yang H, Filmus J, Hawley RG, Bruchovsky N, Cheng H, Matusik RJ, Giguere V 1994. Inhibition of nuclear hormone receptor activity by calreticulin. Nature 367:480–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moilanen AM, Poukka H, Karvonen U, Hakli M, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ 1998. Identification of a novel RING finger protein as a coregulator in steroid receptor-mediated gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol 18:5128–5139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeong BC, Hong CY, Chattopadhyay S, Park JH, Gong EY, Kim HJ, Chun SY, Lee K 2004. Androgen receptor corepressor-19 kDa (ARR19), a leucine-rich protein that represses the transcriptional activity of androgen receptor through recruitment of histone deacetylase. Mol Endocrinol 18:13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong CY, Gong EY, Kim Kim K, Suh JH, Ko HM, Lee HJ, Choi HS, Lee K 2005. Modulation of the expression and transactivation of androgen receptor by the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Pod-1 through recruitment of histone deacetylase 1. Mol Endocrinol 19:2245–2257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Launoit Y, Veilleux R, Dufour M, Simard J, Labrie F 1991. Characteristics of the biphasic action of androgens and of the potent antiproliferative effects of the new pure antiestrogen EM-139 on cell cycle kinetic parameters in LNCaP human prostatic cancer cells. Cancer Res 51:5165–5170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen S, Xu Y, Yuan X, Bubley GJ, Balk SP 2006. Androgen receptor phosphorylation and stabilization in prostate cancer by cyclin-dependent kinase 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:15969–15974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reutens AT, Fu M, Wang C, Albanese C, McPhaul MJ, Sun Z, Balk SP, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ, Pestell RG 2001. Cyclin D1 binds the androgen receptor and regulates hormone-dependent signaling in a p300/CBP-associated factor (P/CAF)-dependent manner. Mol Endocrinol 15:797–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zwijsen RM, Buckle RS, Hijmans EM, Loomans CJ, Bernards R 1998. Ligand-independent recruitment of steroid receptor coactivators to estrogen receptor by cyclin D1. Genes Dev 12:3488–3498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Markus SM, Taneja SS, Logan SK, Li W, Ha S, Hittelman AB, Rogatsky I, Garabedian MJ 2002. Identification and characterization of ART-27, a novel coactivator for the androgen receptor N terminus. Mol Biol Cell 13:670–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aarnisalo P, Palvimo JJ, Janne OA 1998. CREB-binding protein in androgen receptor-mediated signalling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:2122–2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frønsdal K, Engedal N, Slagsvold T, Saatcioglu F 1998. CREB binding protein is a coactivator for the androgen receptor and mediates cross-talk with AP-1. J Biol Chem 273:31853–31859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alen P, Claessens F, Verhoeven G, Rombauts W, Peeters B 1999. The androgen receptor amino-terminal domain plays a key role in p160 coactivator-stimulated gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol 19:6085–6097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma H, Hong H, Huang SM, Irvine RA, Webb P, Kushner PJ, Coetzee GA, Stallcup MR 1999. Multiple signal input and output domains of the 160-kilodalton nuclear recep-tor coactivator proteins. Mol Cell Biol 19:6164–6173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bevan CL, Hoare S, Claessens F, Heery DM, Parker MG 1999. The AF1 and AF2 domains of the androgen receptor interact with distinct regions of SRC1. Mol Cell Biol 19:8383–8392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeh S, Chang C 1996. Cloning and characterization of a specific coactivator, ARA70, for the androgen receptor in human prostate cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:5517–5521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao T, Brantley K, Bolu E, McPhaul MJ 1999. RFG (ARA70, ELE1) interacts with the human androgen receptor in a ligand-dependent fashion, but functions only weakly as a coactivator in cotransfection assays. Mol Endocrinol 13:1645–1656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee YS, Kim HJ, Lee HJ, Lee JW, Chun SY, Ko SK, Lee K 2002. Activating signal cointegrator 1 is highly expressed in murine testicular Leydig cells and enhances the ligand-dependent transactivation of androgen recep-tor. Biol Reprod 67:1580–1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chattopadhyay S, Gong EY, Hwang M, Park E, Lee HJ, Hong CY, Choi SH, Cheong JH, Kwon HB, Lee K 2006. The CCAAT enhancer-binding protein-α negatively regulates the transactivation of androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol 20:984–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee SK, Anzick SL, Choi JE, Bubendorf L, Guan XY, Jung YK, Kallioniemi OP, Kononen J, Trent JM, Azorsa D, Jhun BH, Cheong JH, Lee YC, Meltzer PS, Lee JW 1999. A nuclear factor, ASC-2, as a cancer-amplified transcriptional coactivator essential for ligand-dependent transactivation by nuclear receptors in vivo. J Biol Chem 274:34283–34293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong CY, Park JH, Seo KH, Kim JM, Im SY, Lee JW, Choi HS, Lee K 2003. Expression of MIS in the testis is downregulated by TNF-through the negative regulation of SF-1 transactivation by NF-κB. Mol Cell Biol 23:6000–6012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]