Abstract

Human (h) GH plays an essential role in growth and metabolism, and its effectiveness is modulated by the availability of its specific receptor [hGH receptor (hGHR)] on target cells. The hGHR gene has a complex 5′-regulatory region containing multiple first exons. Seven are clustered within two small regions: V2,V3,V9 (module A) and V1,V4,V7,V8 (module B). Module A-derived mRNAs are ubiquitously expressed whereas those from module B are only found in postnatal liver, suggesting developmental- and liver-specific regulation of module B hGHR gene expression. To characterize the elements regulating module B activity, we studied a 1.8-kb promoter of the highest expressing exon in liver, V1. This promoter was repressed in transfection assays; however, either 5′- or 3′-deletions relieved this, suggesting the presence of multiple negative regulatory elements. Six putative hepatic nuclear factor 4 (HNF-4) response elements were identified. We determined that HNF-4α is developmentally regulated in the human liver: HNF-4α2 and HNF-4α8 are expressed in fetal hepatocytes but only HNF-4α2 is expressed in postnatal liver. Transient transfection assays demonstrated that HNF-4α2 and HNF-4α8 have a similar dual effect on V1 transcription: activation via site 1 in the proximal promoter and repression through site 6, approximately 1.7 kb upstream. EMSA/electrophoretic mobility supershift assays and chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses confirmed these two sites are bound by HNF-4α. Based on these data, we speculate there are multiple regions working together to repress the expression of V1 hGHR transcripts in tissues other than the normal postnatal liver, and that HNF-4α is a good candidate for regulating V1 hGHR expression in the human hepatocyte.

GH PLAYS AN IMPORTANT role in growth and metabolism, with major effects in the liver, adipose tissue, muscle, and bone (1). GH exerts its effects through its specific receptor (GHR), a single-transmembrane class I cytokine receptor devoid of intrinsic catalytic activity. After GH binding to its dimerized receptor, the two GHRs and their associated JAK2 molecules become phosphorylated, activating a series of intracellular signaling pathways (2).

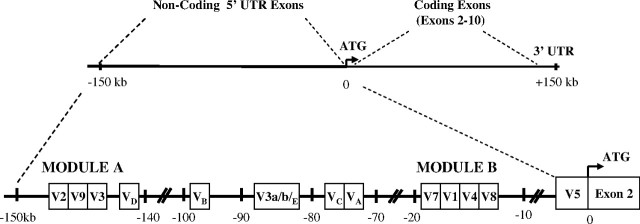

The human (h) GHR is encoded by exons 2–10 of the hGHR gene (Fig. 1) (3). The 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) is highly complex in that it contains 13 first exons that give rise to different mRNA transcripts [V1-V5, V7-V9, V3a/b, VA-E]; V6 is now considered to be an artifact (4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Transcripts derived from these 5′-UTR exons all splice into exon 2, 12 nucleotides upstream of the translational start site and, thus, code for the same protein. Seven of the 5′-UTR exons are clustered in two small regions (1.6 and 2 kb), which we have named module A and module B, respectively (4). mRNAs derived from the exons of module A (V2,V3,V9) are ubiquitously expressed, whereas transcripts arising from exons in module B (V1,V4,V7,V8) are found only in normal human postnatal liver, where V1 is the most abundant transcript (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the hGHR Gene

The hGHR gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 5. Exons 2–10 code for the protein. Thirteen noncoding exons have been reported within the 150 kb upstream of exon 2 in the 5′-UTR (4 5 7 8 ). Seven of the noncoding exons are clustered in two small regions defined as module A (∼1.6 kb) and module B (∼2 kb). VA, VB, VC, VD, and V3a/b/E are found between the two modules. V5 is located adjacent to the first coding exon, exon 2.

Previous findings in our laboratory have shown that the levels of hGHR mRNA and hGH binding in the liver are dramatically increased after birth (4, 9). This increase can be partially explained by the postnatal onset of expression of the module B liver-specific variant mRNAs. We have speculated, therefore, that there are developmental and liver-enriched transcription factors regulating the expression of module B transcripts, especially V1.

Hepatic nuclear factor 4α (HNF-4α) is a prime candidate because it has six putative sites upstream of the V1 exon transcriptional start sites (supplemental Fig. 1 published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). HNF-4α is a liver-enriched transcription factor that has been shown to be an important regulator of the expression of several liver-specific genes (10, 11, 12, 13). There are nine isoforms of HNF-4α due to alternative gene promoter usage (P1 and P2), a possible 30-bp inclusion in the carboxy terminus, and a potential truncation of the carboxy terminus (supplemental Fig. 2). Isoforms arising from the P1 promoter (α1–α6) have been shown to be strongly expressed in the adult and differentiated cell types and have been shown to be transcriptionally more active than those from the P2 promoter (14, 15). P2 isoforms (α7–α9) are predominant in fetal liver, undifferentiated cell types, and stem cell populations in the mouse (16, 17). Thus, the different developmentally regulated isoforms of HNF4α are good candidates for transcriptional regulation of V1. Indeed, HNF-4α1 (P1) has already been shown to be a transcriptional regulator of the bovine b1A GHR variant (equivalent to the human V1) (18, 19).

In preliminary studies, we found that immunoreactive HNF-4α2 (P1) and α8 (P2) proteins are present in human fetal hepatocytes whereas only HNF-4α2 is detected in the postnatal liver. We hypothesized that HNF-4α is involved in the transactivation of the hGHR V1 variant and that the presence of HNF-4α8 dampens the transactivational potential of HNF-4α2, thereby repressing the expression of the V1 hGHR variant in fetal life. Using transient transfections, site-directed mutagenesis, EMSA and electrophoretic mobility supershift assays (EMSSA), and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses, we determined that, of the six putative HNF-4 sites in the 1.8-kb region upstream of the V1 start site, site 1 (most proximal to the V1 transcriptional start site) is highly stimulated by, and binds, both HNF-4α2 and α8. The most distal 6 site also showed binding of HNF-4α2 and α8, by EMSA, EMSSA, and ChIP assays; however, both of these isoforms inhibited V1 promoter activity, suggesting that site 6 is a functionally repressed site. Thus, HNF-4α2 and -α8 have similar transcriptional activities but the HNF-4 response elements (1 and 6) have distinctly different regulatory activities. These data suggest a role for HNF-4α in modulating hGHR mRNA expression in human hepatocytes as well as repressing V1 expression in nonhepatic tissues.

RESULTS

Comparison of Module A and B Promoters

Previous studies from this laboratory have shown that module A mRNA variants are expressed in every tissue examined to date and at every developmental stage (4, 7, 9, 22). Module B mRNA variants, however, are expressed only in the postnatal liver (4, 7, 9, 22). These data suggest that hGHR expression is regulated by multiple promoters. To test this, the promoter activities of module A and B exons were examined using transient transfection assays in two human hepatoma (HepG2 and Huh7) and two primate kidney [CV1 and human embryonic kidney (HEK)293] cell lines.

hGHR Variant Expression in Human Fetal Hepatocytes, Adult Liver, and Cell Lines

In a pilot experiment, we determined the background expression of the hGHR variant mRNAs in these cell lines as well as in human fetal and adult hepatocytes (controls). RT-PCR assays showed that all four cell lines express hGHR mRNA, although HepG2 cells have low levels (supplemental Table 5). Adult hepatocytes express all known hGHR variants whereas fetal hepatocytes express all but module B variants, confirming previous studies (4, 7, 9, 22). The hGHR variant profile of the cell lines is similar to fetal hepatocytes: they do not express module B variants. However, they all express module A variants (V2, V3, and V9) and V5, except for HepG2 cells that have undetectable levels of V9, and CV1 cells that have undetectable levels of V3 or V9.

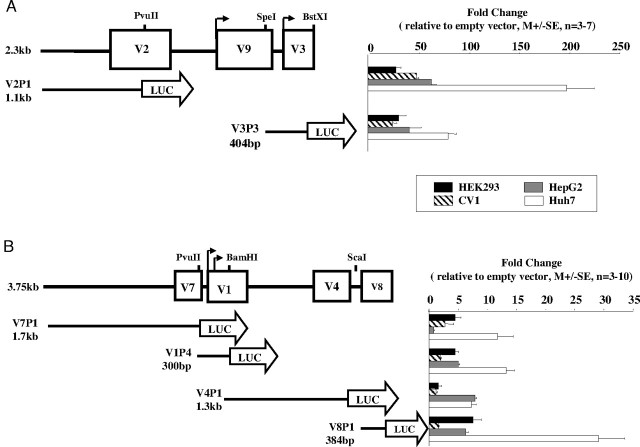

Promoter Activity of Module A and B Promoters

Promoter constructs were prepared to compare the individual promoters from modules A and B, and tested in all four cell lines (Fig. 2), except for V9, which has already been studied (4). We hypothesized that module A constructs will be more active than the liver-specific module B promoter constructs, because the cell lines do not express the liver-specific variants. Indeed, the two module A promoter constructs showed very significant luciferase transcriptional activity, 25- to 200-fold over the promoterless vector, in all cell lines (Fig. 2A), the activity being highest in Huh7 cells, the GH-responsive hepatoma cell line (24). The four module B promoter constructs were also active in all four cell lines but at much lower levels than the module A constructs (Fig. 2, A and B). Surprisingly, V8, an hGHR mRNA variant that is not expressed in any of the cell lines and is the least abundant mRNA variant in adult liver, was the most active, especially in Huh7 cells (M ± se: 29.7 ± 4.5, n = 10) (Fig. 2B). These and previously published V9 data (4) suggest that all seven of the noncoding exons in modules A and B have individual promoter activities.

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional Activity of hGHR Modules A and B Promoter Constructs

Module A (panel A) and module B (panel B) constructs were transfected into HEK293, CV1, HepG2, and Huh7 cells by the CaPO4 method. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection and assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase (internal control) activity. The relative luciferase activity is presented as fold change over the promoterless vector. Data are presented as mean ± se; n = 3–10 experiments.

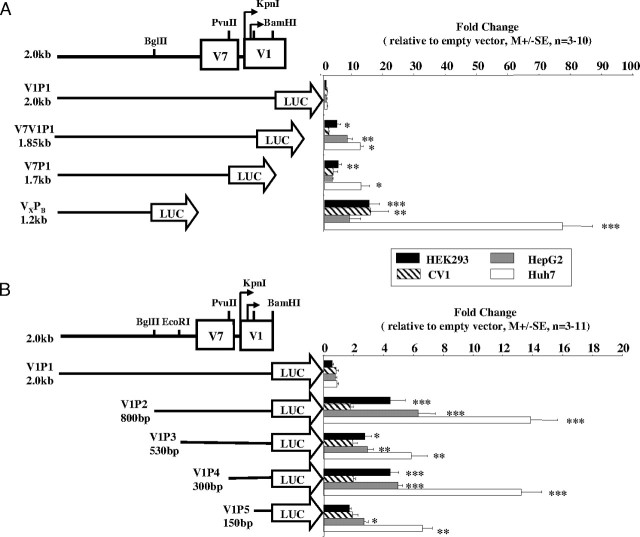

Deletion Analyses of the V7-V1 Promoter

V1 is the most abundant module B variant in the human normal postnatal liver (4, 5, 7, 9). Because its expression pattern suggests both developmental- and tissue-specific regulation, we focused first on characterizing the elements controlling V1 transcriptional activity, by examining a 1.8-kb region upstream of the two transcriptional start sites (TSSs). To identify the regulatory domains, 5′- and 3′-deletional promoter fragments were cloned upstream of the pA3luc vector and tested by transient transfection assays in the four cell lines (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Transcriptional Activity of V1 hGHR Promoter Constructs

3′-Deletion (panel A) and 5′-deletion (panel B) V1 constructs were transfected into HEK293, CV1, HepG2, and Huh7 cells by the CaPO4 method. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection and assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase (transfection control) activities. The relative luciferase activity is presented as fold change over activity obtained using the promoterless vector. Data are presented as mean ± se from n = 3–11 experiments. The significance of the observed differences (compared with V1P1) was determined by Bonferroni’s statistical test following an ANOVA analysis: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

The longest construct, V1P1, containing the V7 exon and 168 bp of the V1 exon, was strongly repressed in all four cell lines (Fig. 3A). When 150 bp were deleted from the 3′-end (V7V1P1 construct, 1.85 kb), there was a significant increase in luciferase activity in HEK293 (3.9 ± 1.3; n = 4, P < 0.05), HepG2 (7.2 ± 1.8; n = 5, P < 0.01) and Huh7 (11.5 ± 0.9; n = 7, P < 0.05) cells. When another 3′ 150 bp were deleted (V7P1 construct: 1.7 kb), similar activities were observed. A further 3′ 0.5-kb deletion (VXPB construct: 1.2 kb) led to an even greater increase in reporter activity in all four cell lines: HEK293 (14.3 ± 3.2; n = 4, P < 0.001), CV1 (14.8 ± 5.7; n = 3, P < 0.01), HepG2 (7.88 ± 3.77; n = 3, P > 0.05), and Huh7 (76.3 ± 9.5; n = 5, P < 0.001). These deletional construct data indicate multiple inhibitory elements within the 3′ 0.8-kb region.

When we analyzed constructs with 5′-deletions (Fig. 3B), we found that a construct with a 1.2-kb deletion of the 5′-region (V1P2) showed a significant increase in transcriptional activity in HEK293 (4.4 ± 1.0; n = 11, P < 0.001), HepG2 (6.3 ± 1.1; n = 4, P < 0.001), and Huh7 cells (13.9 ± 1.8; n = 8, P < 0.001). A further 5′ loss of 270 bp (V1P3) led to a general decrease in activity although levels were still higher than with V1P1 (HEK293: 2.7 ± 0.4; n = 7, NS; HepG2: 2.9 ± 0.4; n = 6, P < 0.01; Huh7: 5.9 ± 1.1; n = 9, P < 0.01). Subsequent loss of another 230 bp (V1P4) resulted in a marked increase in activity in HEK293 (4.5 ± 0.6; n = 10, P < 0.001), HepG2 (5 ± 0.3; n = 5, P < 0.001), and Huh7 (13.2 ± 1.4, n = 5, P < 0.001) cells, similar to V1P2. The V1P5 construct, containing the conserved downstream TATA box and TSS, approximately 100 bp of its promoter, and 43 bp of the V1 exon, showed minimal promoter activity in HEK293 cells (1.7 ± 0.9; n = 7, NS) and CV1 cells (1.92 ± 0.35; n = 4, NS), and lower but still significant activity in HepG2 (2.7 ± 0.3; n = 6, P < 0.05) and Huh7 (6.6 ± 0.7; n = 8, P < 0.01) cells. These data demonstrate additional inhibitory elements within the 5′ 1.2-kb region.

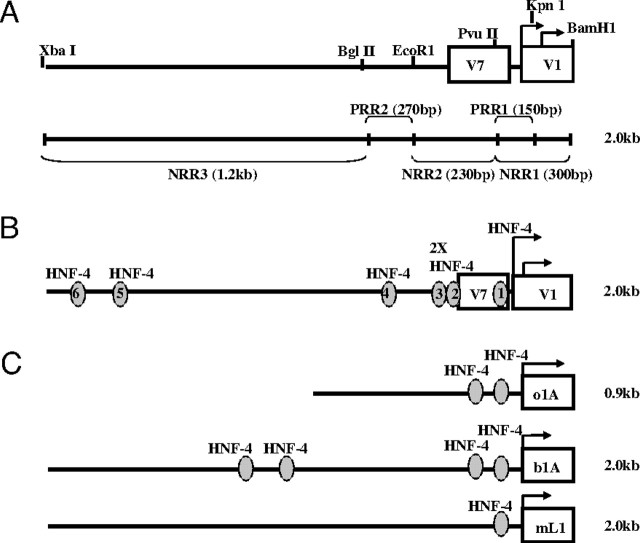

Based on these 3′- and 5′-deletional construct studies, we have defined three negative regulatory regions (NRRs) within the 1.8-kb V1 promoter (NRR 1–3) (Fig. 4A). The first (NRR1) is the most 3′ 300-bp end of the V1P1 construct containing both TATA/TSS complexes of V1. NRR2 is defined as the 230-bp region immediately upstream and, finally, NRR3 is the 5′ 1.2-kb region. Two positive regulatory regions (PRR 1–2) have also been identified: PRR1 is the 5′ 150-bp region of NRR1 and contains the upstream TATA/TSS complex as well as approximately 130 bp of its proximal promoter. PRR2 is the 270-bp region between NRR2 and NRR3.

Fig. 4.

Putative Regulatory Regions of the hGHR V1 Promoter

A, NRRs and PRRs of the V1 promoter as identified by deletion promoter studies. Specific restriction enzyme sites used in the cloning of the promoter constructs are indicated. B, Putative HNF-4 binding sites identified by MatInspector and Signal Scan software programs in the 1.8-kb hGHR V1 promoter (AF322015) (4 ) and in (C) ovine (o1A), bovine (b1A), and mouse (mL1) homologous regions (26 28 30 ). Oval, HNF-4 response element.

Identifying Putative Liver-Enriched Transcription Factors Involved in Regulation of the V1 hGHR Variant mRNA

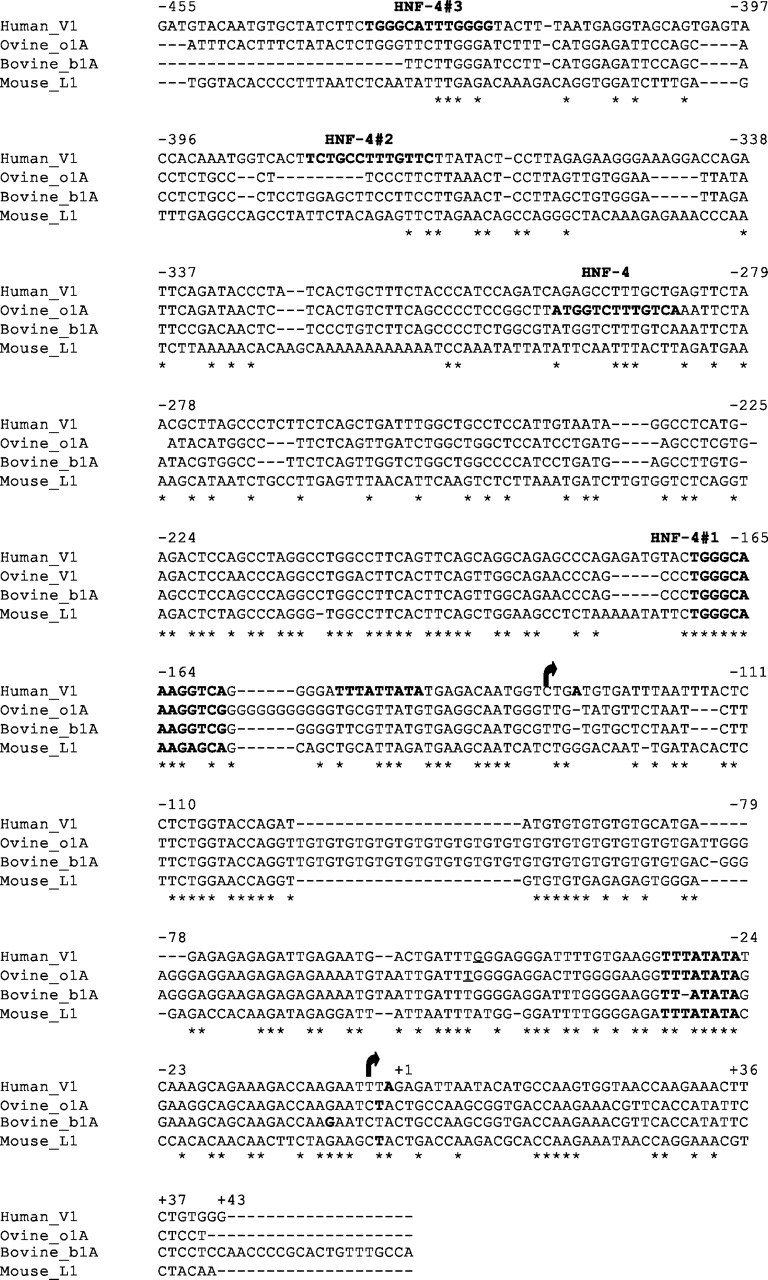

The 1.8-kb V1 promoter sequence was analyzed by the MatInspector computer-based transcription factor-scanning program (25). Putative binding sites for several liver-enriched transcription factors were identified, including for CCAAT enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), several HNFs (HNF-1, HNF-4, HNF-6) and D-binding protein (DBP). Of particular interest was HNF-4, which has six putative sites upstream of V1 (Fig. 4B and supplemental Fig. 1). The site closest to the upstream V1 TATA/TSS complex is conserved across several species (ovine, bovine, and murine) (Fig. 4C and Table 1) (26, 27, 28, 29, 30). Comparing the six putative V1 HNF-4 binding site sequences to the previously published sequences for HNF-4 (10) revealed that the site closest to the TSS (1) is also most similar to what has been defined as the consensus element (supplemental Fig. 1). In contrast, no HNF4 sites were detected in the module A promoters.

Fig. 10.

Alignment of Human V1, Ovine o1A, Bovine b1A, and Mouse mL1 GHR Sequences

Human V1 sequence (AF322015; 500 bp) (4 ) aligned with the ovine (26), bovine (U15731) (28 ) and mouse (NT_039747) (30 ) equivalents. TSS (bold and italicized), TATA boxes (bold), and putative HNF-4 sites (bold) are indicated. The human V1 has two TATA/TSS complexes; the downstream TATA/TSS is conserved in the ovine, bovine, and mouse. *, Conserved nucleotides; arrow, upstream TSS; +1, conserved transcriptional start site.

HNF-4α mRNA and Protein Expression in Human Liver and Cell Lines

HNF-4α has been shown to have nine possible isoforms (supplemental Fig. 2). Using primers for specific regions of the HNF-4 gene (supplemental Table 2), we characterized the mRNA transcripts expressed in human fetal and adult hepatocytes, as well as in three human cell lines (HepG2, Huh7, and HEK293). Transcripts arising from the P1 promoter were found in all cell types and in both fetal and adult liver (supplemental Table 6). Cells from the hepatic lineage also expressed transcripts for HNF-4α with or without the extra 30 bp in the C terminus, for the C-terminal truncated isoforms, and for the isoforms transcribed from the P2 promoter (supplemental Table 6). In contrast, HEK293 cells appeared to produce only the transcript for HNF-4α1.

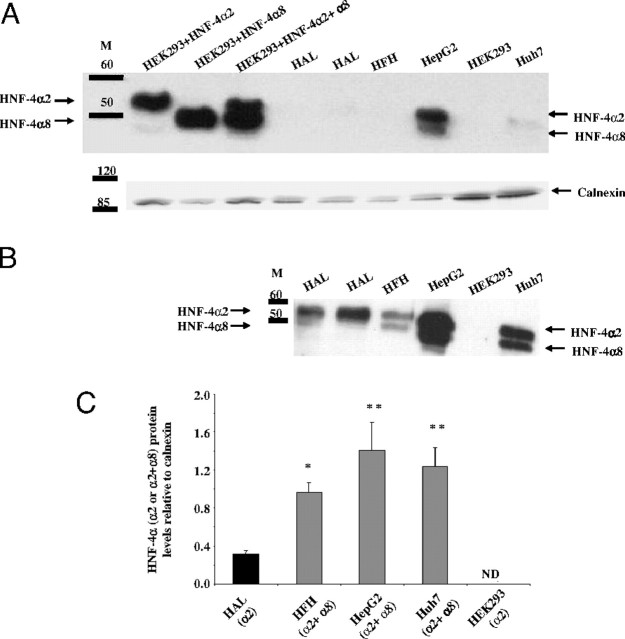

An HNF-4α antibody that can identify isoforms 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8, showed the presence of HNF-4α2 in human fetal hepatocytes, adult liver, and the two hepatoma cell lines whereas HEK293 cells had undetectable levels of HNF-4α protein (Fig. 5, A and B). Interestingly, fetal hepatocytes and the hepatoma cell lines also expressed HNF-4α8 immunoreactive protein in approximately equivalent amounts to HNF-4α2. Analysis of the relative amounts of total HNF-4 present in the samples reveals that fetal hepatocytes and hepatoma cell types have significantly higher levels than adult liver and HEK293 cells (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Detection of HNF-4α Protein in Human Liver and Cell Lines by Western Blot

A, Western blot: cell lines (HEK293 cells or overexpressing HNF-4α2, -α8, or both as well as HepG2 and Huh7) and human fetal hepatocytes (HFH) and human adult liver (HAL) tissues were examined for levels of HNF-4α protein. Nuclear lysates (10–50 μg) were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with anti-HNF-4α that recognizes HNF-4α1, -2, -4, -5, -7, and -8. Calnexin was used as a loading control. B, Extended exposure of Huh7, human adult liver (HAL), and human fetal hepatocyte (HFH) lanes to show HNF-4α2 as the major isoform expressed in HAL, whereas HFH and Huh7 express both HNF-4α2 and -α8 isoforms in equal amounts. C, Cumulative Western blot data expressed as mean ± sd, n = 2–11. HNF-4α was not detected (ND) in HEK293 cells. The significance of the observed differences (compared with HAL) was determined by Bonferroni’s statistical test after an ANOVA analysis: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; M, Markers.

HNF-4α Has a Dual Effect on the V1 Promoter

Initially, our cotransfection studies were carried out with an HNF-4α1 expression vector because this is the isoform used in the majority of published studies on the transcriptional activity of HNF-4α (data not shown; results obtained were similar to α2 and α8). However, because we did not detect HNF-4α1 in our cell and tissue systems but did find the α2 and α8 isoforms (Fig. 5), we changed to HNF-4α2 and α8 expression vectors, in order to have a more biologically relevant test system.

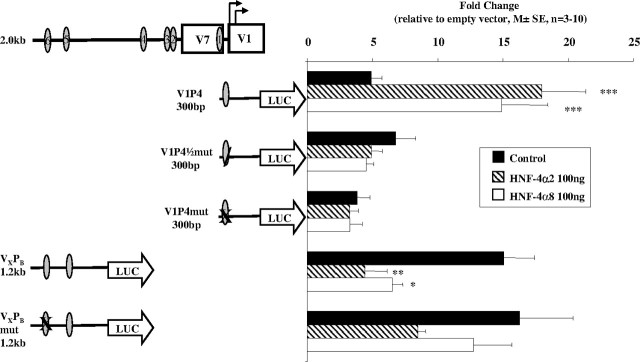

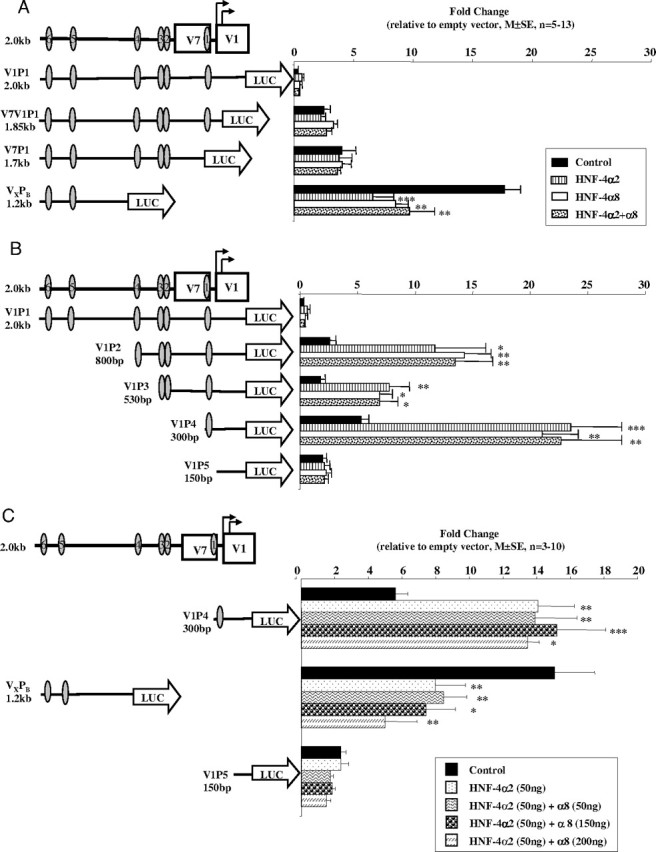

V1P1, the longest and most repressed construct with all six putative HNF-4 sites, did not respond to either HNF-4α2 or α8 (Fig. 6, A and B). There was also no response to the factors when the most 3′ HNF-4 site was deleted (V7P1) (Fig. 6A) although basal activity of the promoter vector was increased. Interestingly, the activity of the promoter region containing only the most 5′ HNF-4 sites (5 and 6) (VXPB) was markedly repressed by HNF-4α2 (P < 0.001) and, to a lesser extent, by HNF-4α8 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6A). Cotransfections of equal amounts of HNF-4α2 and -α8 were equally as effective in repressing VXPB (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Effect of HNF-4α2 and HNF-4α8 on the Transcriptional Activity of V1 Promoter Constructs

HNF-4α2 (100 ng), HNF-4α8 (100 ng), and HNF-4α2+α8 (50 ng + 50 ng) expression vectors were cotransfected with (A) 3′- and (B) 5′-deleted V1 constructs in HEK293 cells using Polyfect. Data are presented as mean ± se; n = 5–13. C, HNF-4α2 (50 ng) and varying amounts of HNF-4α8 (50–200 ng) were cotransfected with V1P4, VXPB, and V1P5 constructs into HEK293 cells. Cells were harvested 48 h later and assayed as before. Data are presented as mean ± se; n = 3–10 experiments. The significance of the differences observed was determined by ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s group comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Oval, HNF-4 response element.

Loss of the 5′ 1.2 kb [sites 5 and 6 (V1P2)] led to a significant stimulation of transcriptional activity by both HNF-4α2 (P < 0.05) and -α8 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6B). Deleting the putative HNF-4 site 4 caused a significant decrease in the stimulatory effect of the HNF-4 factors (V1P3), whereas deleting sites 2 and 3 (V1P4), leaving only the most consensus HNF-4 binding site, led to a significant increase in responsiveness to both isoforms of HNF-4α (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6B). As expected, the V1P5 construct with no HNF-4 sites had no response to the HNF-4 factors.

Interactions of HNF-4α2 and α8 Isoforms

P1 isoforms have activation domains in both the N and C termini whereas P2 isoforms of HNF-4α contain only one activation domain in the C terminus. On some promoters, the effects of P1 isoforms (e.g. α1) are greater than P2 isoforms (e.g. α7), probably due to the fact that the latter lack the N-terminal activation domain that has been shown to interact with coactivators (14, 31). Because both HNF-4α2 and -α8 are present in human hepatoma cell lines and fetal hepatocytes, where V1 is not expressed, we hypothesized that HNF-4α8 dampened the transcriptional potential of HNF-4α2. We therefore tested the effect of increasing doses of HNF-4α8 on both the activating and inhibitory potential of HNF-4α2, using constructs containing our most consensus HNF-4 binding site (V1P4) and the most 5′-sites (VXPB). Increasing doses of HNF-4α8 had no added effect on the response to HNF-4α2 at either of the sites (Fig. 6C).

Site-Directed Mutagenesis of the Putative HNF-4 Sites 1 and 6

To confirm that the proximal 1 and distal 6 putative HNF-4 sites are truly HNF-4α response elements, we mutated the sequences (supplemental Table 3) and tested their responses to HNF-4α2 and -α8. Mutagenesis of site 1 in the V1P4 construct, either as a half- or full-site mutation, completely abolished responsiveness to both HNF-4α2 and -α8 (Fig. 7). In addition, significant repression of the 1.2-kb VXPB construct by both HNF-4α2 and -α8 was lost when the HNF-4 site 6 was mutated. Mutagenesis of site 5 was not carried out because parallel EMSA and ChIP studies indicated that this site was not functional (see below). Thus, HNF-4 sites 1 and 6 appear to be functional stimulatory and inhibitory elements, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Mutational Analysis of HNF-4 Sites 1 (Most 3′) and 6 (Most 5′) in the Proximal Promoter of V1

Constructs with either the HNF-4 binding sites 1 or 6 mutated (supplemental Table 3) were cotransfected with HNF-α2 or -α8; nonmutated constructs were transfected as controls. Data are presented as mean ± se, n = 3–10 experiments. The significance of the differences observed was determined by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s statistical test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Oval, HNF-4 response element; oval with diagonal line, ½ mutated HNF-4 response element; oval with cross, mutated HNF-4 response element.

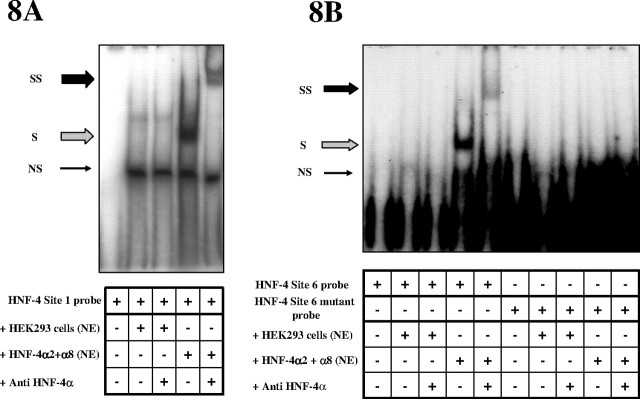

EMSA and EMSSA Analyses of the Putative HNF-4 Sites

EMSAs revealed that HNF-4α2 and -α8 bind to the 1 site (Fig. 8A). Competition studies with an LF-A1 probe containing a known binding site exclusively for HNF-4 (32) diminished the intensity of the shift with overexpression of HNF-4α2 and -α8 (data not shown). The complex was also completely supershifted by an HNF-4α antibody that recognizes isoforms α1, α2, α4, α5, α7, and α8 (Fig. 8A). The partial and double mutants of this site showed only nonspecific binding that was not supershifted by HNF-4α antibody (data not shown). The HNF-4 site 5 did not bind HNF-4α2 or -α8 as detected by gel shift and supershift analyses (data not shown). Site 6, however, specifically bound HNF-4α2 and -α8, and this binding was lost with the mutant probe (Fig. 8B). Identical results were obtained when EMSA and EMSSA analyses were carried out with HEK293 nuclear extracts overexpressing either HNF-4α2 or -α8 alone (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

EMSA and EMSSA Analyses of HNF-4α Proteins Binding to Putative HNF-4 Sites 1, 5, and 6 in the V1 Promoter

Double-stranded oligonucleotides representing the (A) 1 and (B) 6 HNF-4 sites (supplemental Table 3) were radioactively labeled and incubated with various nuclear extracts. Mutant oligonucleotides (supplemental Table 3) and a specific HNF-4α antibody that recognizes HNF-4α2+8 were used to determine the specificity of binding. Nuclear extracts were from HEK293 cells (control or overexpressing HNF-4α2 + α8). Arrows indicate NS, nonspecific; S, shift; SS, supershift bands. NE, Nuclear extract.

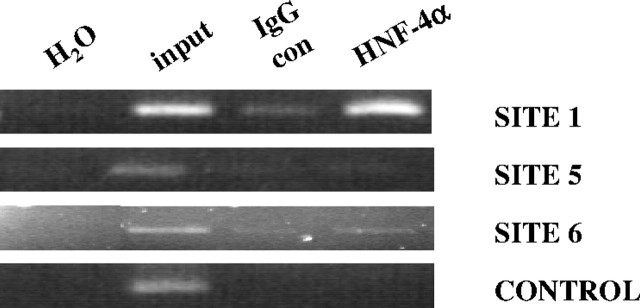

ChIP Analysis of the Putative HNF-4 Sites

In vivo analysis of the HNF-4 sites by ChIP assays in Huh7 cells revealed that the proximal (1) and most distal (6) sites are bound by endogenous HNF-4α, whereas the distal site 5 is not (Fig. 9). We conclude therefore that 1 and 6 are functional HNF-4 sites and 5 is not.

Fig. 9.

In Vivo ChIP Analysis of Proteins Binding to the Two Putative HNF-4 Sites in the V1 Promoter

Huh 7 and HepG2 (data not shown) cells were cross-linked, and the lysates were immunoprecipitated with HNF-4α antibody or goat IgG (con IgG). After the reversal of the cross-links, PCRs were performed across HNF-4 binding sites 1, 5, and 6 and a region 2 kb upstream of HNF-4 site no. 6 as a control (control) (supplemental Table 4). Products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel. con, Control.

DISCUSSION

There are multiple first exons in the 5′-UTR of the hGHR gene, a phenomenon that is conserved across several mammalian species (4). Four of these exons (V1, V4, V7, and V8), found in a cluster about 18 kb upstream of the translational start site, are expressed only in the normal postnatal liver, thus exhibiting a developmental- and hepatic-specific expression pattern (4, 7, 9, 22). A similar expression pattern has been observed for the ovine and bovine exons homologous to V1 (o1A and b1A) whereas the mouse expresses L1 only in the liver of the pregnant female (33). To date, none of the promoter analyses in these other species have identified what cis or trans elements are responsible for the postnatal liver-specific pattern in GHR expression.

V1 is the most abundant hGHR transcript in the human liver and, thus, we were interested in determining how its expression is regulated. We have previously reported the presence of two TATA boxes and two TSSs that are unique to the human V1 exon (4). The downstream TATA is conserved across species and has been described as the functional TATA for the bovine 1A (28), ovine 1A (26), and mouse L1 (30) exons (Fig. 4C). The upstream TATA/TSS has also been described in the human by Zou et al. (35) by Northern blotting and Rivers et al. (34) by 5′-RACE; their start sites for this alternate V1 transcript are reported to be 3 bp upstream and 21 bp downstream of our first TSS (4, 8). To take into account both TATA/TSS complexes for our promoter studies, our longest (2 kb) promoter construct and all of the 5′ deleted versions extend 3′ to 43 bp downstream of the second TSS (BamHI site).

Our comparative studies of putative promoters from modules A and B showed, as expected, that module A promoter constructs for V2 and V3 are highly active in all four cell lines. Promoter studies of V9 have previously shown high activity in the H9C2.2 rat muscle cell line (4). It is likely that these cells contain the necessary transcription factors to drive the ubiquitously expressing promoters and, thus, maintain a level of hGHR expression. Module B variants, on the other hand, were much less active. It is assumed that the hepatoma cell lines do not express module B variants due to their fetal-like state, which could include the presence of active repressors, the lack of transactivators, and/or altered chromatin structure at the hGHR gene locus.

From the initial deletion promoter analysis of the 1.8-kb region upstream of the V1 start sites, three major negative and two positive regulatory regions were identified.

NRR1

NRR1 is the 300-bp region at the 3′-end of V1P1 and includes the two TATA/TSS complexes. Studies of a similar NRR in the V1 promoter by other laboratories or in the equivalent regions in other species have not been reported. However, Jiang and co-workers (36) have determined that a ubiquitous transcription factor, ZBP-89, stimulates the b1A promoter in a region similar to our NRR1. This interaction was first identified by yeast one-hybrid assays because traditional computer assisted-transcription factor searches did not reveal any binding sites for known factors.

NRR2

NRR2 is the 230-bp region just upstream of NRR1. Using deletion promoter studies, Orlovskii et al. (8) describe a 115-bp repressor region in the human V1 promoter equivalent to our NRR2. Footprinting analyses of the human V1 promoter using HepG2 nuclear extracts have uncovered 17-bp (F1) and 28-bp (F2) footprints that overlap with our NRR2; F1 overlaps with our HNF site 2 whereas the F2 footprint encompasses our HNF site 3 (34). Two footprints have been demonstrated with bovine liver nuclear extracts (18) in a homologous region of the b1A promoter; the second was similar to a region in NRR2 that contains our HNF-4 site 3. In the ovine 1A, an approximately 191-bp region homologous to the NRR2 was found to be stimulatory (26).

NRR3

NRR3 occupies the 5′ 1.2-kb region of V1P1. Using deletion promoter studies, Rivers et al. (34) describe a similar region (∼900 bp) containing negative regulatory elements. The bovine 1A also has a 2.2-kb repressor region that overlaps with NRR3 (18). Finally, ovine 1A deletion studies show a 125-bp repressor region overlapping with the 5′-end of the NRR3 (26).

Thus, data from other laboratories and in other species generally support our findings that NRR2 and NRR3 contain repressor elements that regulate the liver-specific expression of hGHR. This study is the first to determine a third important NRR adjacent to the two V1 TSSs.

PRRs

PRR1 is the 5′ 150 bp of NRR1 whereas PRR2 is the 270-bp region between NRR2 and NRR3. Previous studies of the human V1 promoter have not uncovered any positive regulatory regions (8, 34, 35). However, footprinting analyses show that two regions within PRR2 are bound by endogenous HepG2 nuclear proteins; our HNF-4 site 4 is located within the F4 footprint, whereas F3 contains a putative C/EBP site (34).

Deletion promoter studies of the ovine 1A have shown that an approximately 15-bp region similar to our PRR1, and containing a consensus HNF4 site, is also stimulatory. However, an approximately 19-bp region that overlaps with our PRR2 was found to be inhibitory (26). In contrast, the V1 PRR2 region contains the HNF-4 site 4, which we infer from our deletion promoter studies as possibly being stimulatory.

Footprinting studies using bovine nuclear extracts from liver, spleen, and kidney showed binding to a region in the b1A promoter similar to PRR2 (18). Jiang et al. (18, 19) have also shown that HNF-4α1, HNF-4γ, and chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor (COUP-TF)II regulate b1A promoter activity through a consensus HNF4 site in a region homologous to our PRR1. Yeast one-hybrid experiments first identified HNF-4α, HNF-4γ, and COUP-TFII as proteins interacting at the HNF-4 site, and this was confirmed by EMSA, EMSSA, and ChIP assays (19). All three factors stimulated transcriptional activity of a −469/−21-bp b1A proximal promoter construct, the effect of COUP-TFII being about 15-fold higher than the HNF-4 factors. Deletion of the HNF-4 site ablated responses to HNF-4α and HNF-4γ, whereas there was still some response to COUP-TFII, suggesting that COUP-TFII also acts through flanking regions. HNF-4α and HNF-4γ are expressed in hepatocytes; however, HNF-4γ mRNA is 10× less abundant than HNF-4α mRNA (37). COUP-TFII has been shown to be expressed in human liver mesenchymal and ductal cells but not hepatocytes (38). However, a recent paper using a β-galactosidase marker driven by a COUP-TFII promoter did detect expression in murine hepatocytes, leaving the issue of whether COUP-TFII could be involved in liver-specific GHR expression controversial (39). The −469/−21bp b1A construct contains a second putative HNF-4 site that is also present in the ovine but not in the human or mouse (Fig. 5); this site has yet to be investigated.

Thus, the data from these deletion promoter studies have led us to identify five major regulatory regions within the 1.8-kb V1 promoter: three inhibitory and two stimulatory. Regulation of the longest promoter construct (V1P1) suggests that the inhibitory regions interact to markedly repress V1P1 in all of the four cell lines. Interestingly, two of the three negative regulatory regions (NRR2 and NRR3) coincide with the presence of four of the six identified HNF-4 sites (2, 3, 5, and 6). Cotransfection studies with HNF-4 α2 and α8 expression vectors showed that constructs containing the two most 5′ HNF-4 sites (in NRR3) were, in fact, repressed by both factors. The most striking increase in luciferase transcriptional activity of the V1 promoter construct occurred in all four cell lines once the 3′ 150 to 300-bp region (NRR1) was removed. Whereas studies of the distal NRR3 are included in the present paper because of the suggested role of HNF-4α, experiments to investigate the more proximal NRR1 have shown that alternative (Gfi1/1b) transcription factors are involved (Kenth, G. and C. G. Goodyer, in preparation).

HNF-4α is essential for the expression of many genes that are specific and central to liver development and function (40, 13). Conditional HNF-4α knockout adult mice show defects in hepatic lipid, lipoprotein, bile acid and glucose metabolism, and decreased body weight (41). We decided to examine the effect of HNF-4α on V1 expression for several reasons: regulation of the liver-specific V1 is likely to involve a liver-enriched transcription factor such as HNF-4α, six putative HNF-4 binding sites were identified by computer-assisted TF scanning programs, and hGH has also been shown to be involved in the regulation of hepatic lipid, lipoprotein bile acid and glucose metabolism (42).

We first defined the HNF-4α content in human fetal and adult hepatocytes and three human cell lines. Expression of the HNF-4α gene is under the control of two promoters, P1 and P2. Isoforms arising from the promoters are developmentally regulated in the mouse: P2 isoforms are expressed only in the fetal hepatocytes, and P1 isoforms are expressed in both fetal and adult hepatocytes (16, 17). We show for the first time a parallel situation in humans: the HNF-4α8 (P2) isoform was expressed only in the fetal hepatocytes, whereas the HNF-4α2 (P1) isoform was found in both fetal and adult hepatocytes, using an HNF-4α antibody specific to the extreme C terminus of HNF-4α. Other groups have reported expression of the HNF-4α2 isoform in human adult hepatocytes and hepatoma cells (HepG2, Huh7) using HNF-4α antibodies specific to the N terminus that distinguish between P1 and P2 isoforms (14, 43, 44).

HNF-4α2 and -α8 both bind the same sites in the V1 hGHR promoter; this interaction is abolished by mutations in either one or both half-sites of the direct repeat response element, showing that these are functional HNF-4 sites. Because fetal hepatocytes and hepatoma cell lines express HNF-4α8 in addition to HNF-4α2, but not the V1 transcript, we initially hypothesized that the presence of HNF-4α8 inhibited the stimulatory effect of HNF-4α2 on V1 transcription in fetal and tumor hepatic cells. Previous studies suggest that there are functional differences between the P1 and P2 isoforms (45). P2 HNF-4α isoforms that possess only the AF-2 domain are less potent transcription factors (14, 15) but are stronger activators of early genes (31). Insertion of 10 amino acids in the F-domain of HNF-4α1 makes HNF-4α2 a more effective transactivator (46). Our observations of the effect of P1 and P2 HNF-4α isoforms on the V1 promoter reflect this: HNF-4α2 (P1 isoform) had a consistently greater effect, whether stimulatory or inhibitory, on the deletion V1 promoter constructs than HNF-4α8 (P2 isoform). In addition, cotransfecting increasing amounts of HNF-4α8 with HNF-4α2 did not alter its effect on the promoter fragments, disproving our hypothesis that P2 isoforms repress the activity of P1 isoforms and, thereby, inhibit the expression of the liver-specific V1 hGHR transcript in fetal hepatocytes and hepatoma cell lines. Thus, the binding of P1 and P2 isoforms of HNF-4α to the V1 promoter suggests a regulatory role in cells that express either one (adult hepatocytes) or both (fetal hepatocytes) of the isoforms.

In agreement with our observation of the repressive effects of HNF-4α2 and -α8 interactions on the HNF-4 site 6, HNF-4α1 has been shown to act as a repressor on the hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A synthase gene (47), the liver-specific arginase gene (48), the acyl-oxidase gene (49), the IGF-II P1 promoter (50), and the HNF-4αP1 (51) and P2 (52) promoters. Only one other example of a dual effect of HNF4α isoforms on the same gene has been reported: HNF-4α1 has been shown to have both activating and repressive functions on the human α1-microglobulin/bikunin (AMBP) gene (53). Like V1, AMBP mRNA expression is restricted to the liver and up-regulated during the perinatal period, suggesting that this gene is also under tissue and developmental regulation (54). Nine response elements for the HNF family (HNF-1, HNF-3, and HNF-4) are clustered in an enhancer region approximately 2.5 to 2.9 kb upstream of the TSS. Sites 2, 7, and 8 are positive HNF-4 sites whereas HNF-4α1 exerts a negative effect through site 9. The repressive effect is dependent on low levels of HNF-4α: when occupancy of the low-affinity site 8 is low, the inhibitory effect of box 9 becomes more pronounced (53).

There are no distinctive differences in the V1 promoter HNF-4 binding site sequences that might explain why they have either inhibitory or stimulatory effects. One possibility is that, like for the AMBP gene, the absolute levels of nuclear HNF4α are critical as to what effect predominates on the V1 hGHR promoter. It may be that in nonhepatic tissues, where HNF-4α levels are low, repression of V1 is the predominant effect whereas in hepatocytes, where HNF4α levels are relatively high, V1 transcription is stimulated.

HNF4α levels in liver are regulated by factors involved in hepatocyte differentiation and lipid and glucose homeostasis (e.g. HNF-1α/β, HNF-6, HNF3α/β, GATA6, fatty acids, insulin, glucagon, glucocorticoids) (10, 41, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61). Although certain of these factors (e.g. glucocorticoids) (62, 63) have been thought to modulate hepatic hGHR expression directly, our present data suggest that HNF-4α may act as an intermediate.

A second possibility is that repression or activation by HNF-4α is the result of interactions with other transcription factors. In support of this, HNF-4α repression of the human IGF-II gene has been shown to be relieved by C/EBPα (47, 50, 64), whereas HNF4α cooperates with C/EBPα to stimulate the apolipoprotein B (ApoB) gene (65). C/EBPα is expressed at very low levels in the rodent fetal liver and is up-regulated in mature liver (66); thus, C/EBPα could be another mechanism by which V1 expression is augmented postnatally in the liver. However, one major difference exists: whereas the C/EBP and HNF4 response elements are adjacent or overlapping in the IGF-II and ApoB gene promoters, the single putative C/EBP site in the 1.8-kb V1 promoter is quite distant (>800 bp) from either HNF4 site 1 or 6.

The region containing the distal site 6 could be considered to be within the promoter of V7, which is upstream of the V1 exon, or to be a distant regulatory element of V1. As a promoter region of V7, repression of HNF-4 site 6 by both HNF-4α2 and -α8 could be the mechanism regulating the suppression of V7 in the fetal liver and its low expression in adult liver. On the other hand, as a distal regulatory element for V1, it could account for the suppression of V1 expression in fetal liver and, with increased expression around birth of other liver-enriched transcription factors, such as HNF4α and C/EBPα, these factors could alleviate the repression and, in cooperation with site 1, induce V1 expression in the postnatal liver.

The HNF-4 site in PRR1 is conserved across four species: human, bovine, ovine, and mouse. From our V1 experiments, and previous studies of the b1A (18, 19) and o1A (26) variant exons, we believe that this response element is functional and stimulatory in the human, bovine, and ovine GHR genes. It is difficult to speculate whether this is the case for the mouse L1 variant because this transcript is strongly up-regulated only in the liver of pregnant mice and, therefore, is likely to be under additional regulatory mechanisms (30, 33, 67, 67). In fact, studies of the mouse L1 promoter have identified a developmental enhancer element 3.5 kb upstream of the TSS that is only active in adult hepatocytes (30, 67). This element binds nuclear factor Y and MSY-1, a single-stranded binding protein. The amount of immunoreactive MSY-1 protein in the nuclei of nonpregnant mouse liver cells is much higher than in pregnant females, and an MSY-1 expression vector repressed the activity of the 3.6-kb mL1 promoter construct by 50–60%, suggesting that it normally suppresses mL1 expression in nonpregnant mice (67).

We chose to first investigate in detail the putative HNF-4 sites that had sequences closest to the published consensus and also were present in vector constructs that showed striking responses to HNF-4α: V1P4 (site 1 with only 1-bp mismatch) was highly stimulated and VXPB (5 and 6, each with only 2-bp mismatches) was significantly inhibited in response to HNF-4α2 and -α8 (as well as α1; data not shown). Future experiments will investigate the functional significance of the additional three sites (2, 3, 4), and how all six sites may interact to regulate transcription of the V1 mRNA transcript.

In summary, HNF-4α2 and -α8 have comparable effects on expression of the hGHR gene, stimulating and repressing V7/V1 promoter activity via two different promoter sites. We propose that this dual functionality of HNF-4α allows for fine tuning of V7/V1 transcription in hGH target cells. It provides a mechanism to alter which factors regulate hGHR expression and, thus, to modulate the physiological effects of hGH. On the one hand, repression of the V7/V1 promoter in the fetal hepatocyte and all nonhepatic tissues will limit hGHR gene regulation to the promoters of the ubiquitously expressing hGHR exons, resulting in a low but relatively constant level of expression. This is likely important in the fetal hepatocyte because the fetal liver is primarily a hematopoietic organ, and most nutritional input is coming from the mother. In contrast, postnatal loss of this repression specifically in the hepatocyte will enable hGHR expression to also be modulated by liver-specific transcription factors. This will allow for a more precise regulation of hGH physiological effects on hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism by nutritional cues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

The following reagents were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA): HNF-4α C-19 (sc-6556 and sc-6556X), HNF-4α H-171 (sc-8987X), antigoat-horseradish peroxidase (sc-2020), goat IgG (sc-2028), and mouse IgG (sc-2027). Calnexin antibody (C45520) was obtained from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). Antimouse-horseradish peroxidase was purchased from NEN Life Sciences Products, Inc. (Boston, MA). CV1 (African green monkey kidney fibroblasts), HEK293 (human fetal kidney epithelial cells), and HepG2 (human hepatoma cells) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), whereas Huh7 (human hepatoma cells) were kindly provided by Dr. Ken K. Ho (Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia). The HNF-4α1 expression vector was kindly provided by Dr. Elly Holthuizen (University of Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands); the HNF-4α2 and -α8 expression vectors were provided by Dr. Bernard Laine (U 459 Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, France); the pA3luc reporter vector was supplied by Dr. Jacques Drouin (Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) (20); and sp64 and pSV-β-galactosidase were purchased from Promega Corp. (Madison, WI).

Tissues

Human fetal livers were obtained at the time of therapeutic abortions (n = 11, 13.5–19.5 wk); fetal age was determined by foot length (21). Normal human postnatal livers (n = 5, 11–66 yr) were obtained 4–10 h after the removal of a donor liver for pediatric transplantation and after perfusion to remove all blood cells. Tissues were collected after written consent and with the approval of the local ethics committees in compliance with Canadian Institutes of Health Research guidelines. Tissues collected for RNA and protein studies were frozen at −80 C until processed. Tissues for hepatocyte isolation were immediately processed, as detailed below.

Hepatocyte Isolation

Fetal hepatic tissues were minced and dispersed by collagenase, followed by gravity separation, yielding more than 95% pure hepatocytes, as previously described (22). The isolated hepatocytes were plated on collagen-coated petri dishes in William’s E medium (Invitrogen, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/ml penicillin G, 1.6 mg/ml gentamycin sulfate, and 2 μm dexamethasone (Sigma, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The hepatocytes were rinsed thoroughly 2 h after plating (three to five times) with 1× PBS to remove all remaining traces of hematopoietic cells, replaced with fresh, complete William’s E medium with 39.2 μg/ml dexamethasone and incubated overnight. After 24 h, hepatocytes were washed twice with 1× PBS, collected by scraping, and centrifuged at 1000 × g. The resulting pellets were immediately extracted for protein and RNA or frozen at −80 C until required.

Plasmid Construction

For module A, 2.7 kb, and for module B, 4 kb of hGHR genomic DNA were subcloned from a Bac clone (hcit.102E14) into the Bluescript (pSK−) vector (4). Various restriction enzymes were used to digest the DNA, and specific fragments were subcloned upstream of pA3luc (20), a luciferase reporter vector. Serial deletion constructs were created from V2V3P2 (module A) and V1P1 (module B) to study the putative promoter regions within the two modules (Figs. 2 and 3). All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Cell Culture and Transient Transfection Assays

HEK293, CV1, and HepG2 cells were cultured in low-glucose DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics; Huh7 cells were cultured in MEM with Earle’s salts (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS/normal calf serum (1:1) and antibiotics. Cells (1 × 105) were seeded in 12-well plates for 24 h before transfection. Cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of reporter or empty vector, 0.1 μg of pSV-β-galactosidase (Promega Corp.), and 0.05–0.2 μg of HNF-4α2 or -α8 expression vectors; total DNA per well was made up to 1 μg with sp64 and transfected, initially with CaPO4 (Figs. 2 and 3) and later with Polyfect (QIAGEN, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) (Figs. 6 and 7). Cells were harvested 48 h later and the EG&G Berthold MicroLumat Plus bioluminometer (Tropix Galactonstar, Bedford, MA) was used to measure luciferase and β-galactosidase activity. Data are expressed as a ratio of luciferase over β-galactosidase activity and normalized to the empty vector, pA3luc.

RNA Extraction, RT-PCR Assays

RNA was extracted from cell pellets or frozen tissue using Trizol (Invitrogen). Total RNA (5 μg) was reverse transcribed (RT) with Superscript II (Invitrogen), using 200 ng of random primers (Invitrogen) in 20 μl of reaction mix. PCR assays were performed with Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and 3 μl of cDNA from the RT reactions. Primers (supplemental Tables 1 and 2) were purchased from Alpha DNA (Montreal, Quebec, Canada). PCR conditions were as follows: one cycle at 94 C for 2 min followed by amplification for 35 cycles at 94 C for 2 min, 60–70 C for 1 min, 72 C for 1.5 min, ending with 72 C for 5 min. Products were resolved on ethidium bromide-stained 1.5% agarose gels.

Protein Extraction

Tissue.

Frozen tissue (500 mg) was minced in 1–2 ml of 1× RIPA buffer [1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 150 mm NaCl]. The solution was then homogenized in 1× RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, Quebec, Canada) in a Dounce homogenizer. The lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 50 min at 4 C.

Cells.

HEK293, CV1, Huh7, and HepG2 cells were trypsinized and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 15 min at 4 C. Pellets were resuspended in 10× pellet volume of 1× lysis buffer (50 mm Tris HCl, pH 7.5; 0.1% Triton-X 100; 2 mm EDTA) supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors and incubated on ice for 15 min. The cell suspension was then spun at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4 C.

Supernatants from tissue and cell preparations were stored in aliquots at −20 C. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA).

Nuclear Extracts

Nuclear extracts were prepared from both cells and tissues using the NE-PER kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL), following the manufacturer’s instructions. After resuspension of the nuclear pellet in nuclear extraction buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, the nuclear extract was dialysed (Slide-a-Lyser, Pierce) in ice-cold PBS and stored in aliquots at −80 C. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay.

Western Blots

Whole-cell or nuclear protein extracts (10–75 μg) were boiled in 1× SDS loading buffer for 3 min and separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidinedifluoride membrane (Millipore Corp., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) using a wet transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad). The blots were blocked in 5% milk (PBS-Tween 20 or Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20) and probed with goat polyclonal HNF-4α (1:200, SC-6556) or a mouse monoclonal antibody for calnexin (1:1000), as a loading control, for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were then washed once for 15 min and three times for 10 min with PBS-Tween 20/Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 before being incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 1:1000-fold dilution of corresponding secondary antibodies. The blots were exposed to chemiluminescence reagents (ECL kit; PerkinElmer Life Sciences Inc., Boston, MA) and protein-antibody complexes were visualized by autoradiography. Densitometric analyses were carried out using the Bio-Rad Gel Doc analysis system. The data are expressed as a ratio of HNF-4α to calnexin.

EMSA and EMSSA

Double-stranded oligonucleotides were prepared by dissolving 100 nmol/ml complementary oligonucleotides (supplemental Table 3) in annealing buffer (100 nm Tris HCl, pH 7.5; 1 m NaCl; 10 mm EDTA), incubating at 65 C for 10 min, then at room temperature for 1–2 h. The double-stranded oligonucleotides were either end labeled with [γ 32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen) or were fill-in labeled with [α32P]CTP using Klenow fragment (Invitrogen). Labeled probes were purified by G-50 spin columns (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Nuclear extract (6 μg) was preincubated on ice in 1× binding buffer (20 mm HEPES, 5% glycerol, 100 nm KCl, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm MgCl2) and 1μg of polydeoxyinosinic deoxycytidylic acid (Sigma) for 20 min on ice. Labeled probe (0.05 pmol) was added to the mixture and incubated for a further 20 min on ice. In supershift assays, 2 μg of antibody was added to the mixture after the 20 min incubation with the labeled probe and incubated for 1 h at 4 C. The 20-μl reaction was then loaded on 5–10% prerun polyacrylamide gels and electrophoresed at 100 V in cold 0.5× Tris-buffered EDTA. Gels were dried at 80 C for 1 h, and complexes were detected by autoradiography.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Mutations were introduced into the HNF-4 sites using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and the primers listed in supplemental Table 3. The presence of the mutations was confirmed by sequencing before use.

ChIP

ChIP was performed as previously described (10, 23). Briefly, cells (1 × 106) cultured in a 100-mm dish were cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde (ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, OH) for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were scraped and pelleted, and the pellets were resuspended in 300 μl SDS lysis buffer on ice and sonicated twice for 15 sec at 50% input (VibraCell Sonicator, Sonics, Betatek Inc., Toronto, Ontario, Canada). The suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 C. The lysate was diluted 10-fold in ChIP dilution buffer, and 500 μl was kept aside as input. A portion (2 ml) of the remaining lysate was supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and precleared with 2 μg of BSA (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), 4 μg of sonicated herring sperm DNA (Sigma), and 45 μl of protein A/G Plus agarose beads (Santa Cruz) for 30 min at 4 C on a rotating platform. The beads were pelleted and the supernatant immunoprecipitated for 3 h at 4 C, rotating with 4 μg of either goat IgG (control) or anti-HNF-4α. Complexes were pulled down by incubating the above solution overnight with 2 μg of BSA, 4 μg of sonicated herring sperm DNA, and 45 μl of protein A/G Plus agarose beads, rotating at 4 C. Beads were pelleted and washed sequentially with low-salt buffer, high-salt buffer, lithium chloride wash buffer, and 1× Tris-EDTA for 5 min each. Bound protein was eluted twice from the beads by vortexing at the highest speed for 15 sec and gently rotating for 15 min in ChIP extraction buffer at room temperature. Cross-links were reversed overnight at 65 C. DNA was purified with the QIAGEN DNA purification kit. Of the 50 μl purified DNA in elution buffer, 2–5 μl was used per PCR. PCR primers were designed to amplify the individual HNF-4 response elements 1, 5, and 6 (supplemental Table 4). Control primers were designed for a region 2 kb upstream of the HNF-4 site 6.

Statistics

The significance of observed differences between groups was determined by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s group comparison test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the major contributions of Dr. Joy Osafo to this manuscript. Dr. Osafo has chosen not to be first author for reasons relating to her religious beliefs. We also acknowledge the generous gifts of HNF-4α1 expression vector from Dr. Elly Holthuizen (University of Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands), HNF-4α2 and -α8 expression vectors from Dr. Bernard Laine (U 459 Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, France), the pA3luc reporter vector from Dr. Jacques Drouin (Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada), and the Huh 7 cells from Dr. Ken K. Ho (Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia).

NURSA Molecule Pages:

Nuclear Receptors: HNF4α.

Footnotes

This work was supported by funds from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to C.G.G.).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online November 8, 2007

Abbreviations: C/EBP, CCAAT enhancer binding protein; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; COUP-TF, chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor; EMSSA, electrophoretic mobility supershift assay; FBS, fetal bovine serum; GHR, GH receptor; HEK, human embryonic kidney; HNF, hepatic nuclear factor; NRR, negative regulatory region; PRR, positive regulatory region; RT, reverse transcriptase; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; TSS, transcriptional start site; UTR, untranslated region.

References

- 1.Veldhuis JD, Roemmich JN, Richmond EJ, Rogol AD, Lovejoy JC, Sheffield-Moore M, Mauras N, Bowers CY 2005. Endocrine control of body composition in infancy, childhood, and puberty. Endocr Rev 26:114–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gent J, Van Den EM, van Kerkhof P, Strous GJ 2003. Dimerization and signal transduction of the growth hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 17:967–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung DW, Spencer SA, Cachianes G, Hammonds RG, Collins C, Henzel WJ, Barnard R, Waters MJ, Wood WI 1987. Growth hormone receptor and serum binding protein: purification, cloning and expression. Nature 330:537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodyer CG, Zogopoulos G, Schwartzbauer G, Zheng H, Hendy GN, Menon RK 2001. Organization and evolution of the human growth hormone receptor gene 5′ flanking region. Endocrinology 142:1923–1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pekhletsky RI, Chernov BK, Rubtsov PM 1992. Variants of the 5′-untranslated sequence of human growth hormone receptor mRNA. Mol Cell Endocrinol 90:103–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank SJ 2001. Growth hormone signalling and its regulation: preventing too much of a good thing. Growth Horm IGF Res 11:201–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei Y, Rhani Z, Goodyer CG 2006. Characterization of growth hormone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid variants in human adipocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:1901–1908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orlovskii IV, Sverdlova PS, Rubtsov PM 2004. [Fine structure, expression and polymorphism of the human growth hormone receptor gene]. Mol Biol (Mosk) 38:29–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodyer CG, Figueiredo R, Krackovitch S, DeSouza Li L, Manalo J, Zogopoulos G 2001. Characterisation of the growth hormone receptor in human dermal fibroblasts and liver during development. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 281:E1213–E1220 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sladek F, Seidel S 2001. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 α. In: Burris T, McCabe E, eds. Nuclear receptors and genetic disease. San Diego: Academic Press; 309–361

- 11.Schrem H, Klempnauer J, Borlak J 2002. Liver-enriched transcription factors in liver function and development. I. The hepatocyte nuclear factor network and liver-specific gene expression. Pharmacol Rev 54:129–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemaigre F, Zaret KS 2004. Liver development update: new embryo models, cell lineage control, and morphogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev 14:582–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Odom DT, Zizlsperger N, Gordon DB, Bell GW, Rinaldi NJ, Murray HL, Volkert TL, Schreiber J, Rolfe PA, Gifford DK, Fraenkel E, Bell GI, Young RA 2004. Control of pancreas and liver gene expression by HNF transcription factors. Science 303:1378–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ihara A, Yamagata K, Nammo T, Miura A, Yuan M, Tanaka T, Sladek FM, Matsuzawa Y, Miyagawa J, Shimomura I 2005. Functional characterization of the HNF4α isoform (HNF4α8) expressed in pancreatic β-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 329:984–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eeckhoute J, Moerman E, Bouckenooghe T, Lukoviak B, Pattou F, Formstecher P, Kerr-Conte J, Vandewalle B, Laine B 2003. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 α isoforms originated from the P1 promoter are expressed in human pancreatic β-cells and exhibit stronger transcriptional potentials than P2 promoter-driven isoforms. Endocrinology 144:1686–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torres-Padilla ME, Fougere-Deschatrette C, Weiss MC 2001. Expression of HNF4α isoforms in mouse liver development is regulated by sequential promoter usage and constitutive 3′ end splicing. Mech Dev 109:183–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakhei H, Lingott A, Lemm I, Ryffel GU 1998. An alternative splice variant of the tissue specific transcription factor HNF4α predominates in undifferentiated murine cell types. Nucleic Acids Res 26:497–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang H, Lucy MC 2001. Involvement of hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 in the expression of the growth hormone receptor 1A messenger ribonucleic acid in bovine liver. Mol Endocrinol 15:1023–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Q, Walther N, Jiang H 2004. Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor II (COUP-TFII) and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4γ (HNF-4γ) and HNF-4α regulate the bovine growth hormone receptor 1A promoter through a common DNA element. J Mol Endocrinol 32:947–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodyer CG, Tremblay JJ, Paradis F, Marcil A, Lanctot C, Gauthier Y, Drouin J 2003. Pitx1 promoter activity and mechanisms of positive autoregulation. Neuroendocrinology 78:129–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munsick RA 1984. Human fetal extremity lengths in the interval from 9 to 21 menstrual weeks of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 149:883–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zogopoulos G, Albrecht S, Pietsch T, Alpert L, von Schweinitz D, Lefebvre Y, Goodyer CG 1996. Fetal- and tumor-specific regulation of growth hormone receptor mRNA expression in human liver. Cancer Res 56:2949–2953 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang TT, Nestel FP, Bourdeau V, Nagai Y, Wang Q, Liao J, Tavera-Mendoza L, Lin R, Hanrahan JW, Mader S, White JH 2004. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J Immunol 173:2909–2912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mullis PE, Holl RW, Lund T, Eble A, Brickell PM 1995. Regulation of human growth hormone-binding protein production by human growth hormone in a hepatoma cell line. Mol Cell Endocrinol 111:181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cartharius K, Frech K, Grote K, Klocke B, Haltmeier M, Klingenhoff A, Frisch M, Bayerlein M, Werner T 2005. MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics 21:2933–2942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Mahoney JV, Brandon MR, Adams TE 1994. Identification of a liver-specific promoter for the ovine growth hormone receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol 101:129–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heap D, Lucy MC, Collier RJ, Boyd CK, Warren WC 1995. Rapid communication: nucleotide sequence of the promoter and first exon of the somatotropin receptor gene in cattle. J Anim Sci 73:1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang H, Lucy MC 2001. Variants of the 5′-untranslated region of the bovine growth hormone receptor mRNA: isolation, expression and effects on translational efficiency. Gene 265:45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Southard JN, Barrett BA, Bikbulatova L, Ilkbahar Y, Wu K, Talamantes F 1995. Growth hormone (GH) receptor and GH-binding protein messenger ribonucleic acids with alternative 5′-untranslated regions are differentially expressed in mouse liver and placenta. Endocrinology 136:2913–2921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menon RK, Stephan DA, Singh M, Morris Jr SM, Zou L 1995. Cloning of the promoter-regulatory region of the murine growth hormone receptor gene. Identification of a developmentally regulated enhancer element. J Biol Chem 270:8851–8859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torres-Padilla ME, Weiss MC 2003. Effects of interactions of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α isoforms with coactivators and corepressors are promoter-specific. FEBS Lett 539:19–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall RK, Sladek FM, Granner DK 1995. The orphan receptors COUP-TF and HNF-4 serve as accessory factors required for induction of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase gene transcription by glucocorticoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:412–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ilkbahar YN, Southard JN, Talamantes F 1999. Transcriptional upregulation of hepatic GH receptor and GH-binding protein expression during pregnancy in the mouse. J Mol Endocrinol 23:85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rivers CA, Norman MR 2000. The human growth hormone receptor gene–characterisation of the liver-specific promoter. Mol Cell Endocrinol 160:51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou L, Burmeister LA, Sperling MA 1997. Isolation of a liver-specific promoter for human growth hormone receptor gene. Endocrinology 138:1771–1774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Q, Springer L, Merchant JL, Jiang H 2006. Identification of zinc finger binding protein 89 (ZBP-89) as a transcriptional activator for a major bovine growth hormone receptor promoter. Mol Cell Endocrinol 251:88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drewes T, Senkel S, Holewa B, Ryffel GU 1996. Human hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 isoforms are encoded by distinct and differentially expressed genes. Mol Cell Biol 16:925–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki T, Moriya T, Darnel AD, Takeyama J, Sasano H 2000. Immunohistochemical distribution of chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor II in human tissues. Mol Cell Endocrinol 164:69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang P, Bennoun M, Gogard C, Bossard P, Leclerc I, Kahn A, Vasseur-Cognet M 2002. Expression of COUP-TFII in metabolic tissues during development. Mech Dev 119:109–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Battle MA, Konopka G, Parviz F, Gaggl AL, Yang C, Sladek FM, Duncan SA 2006. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α orchestrates expression of cell adhesion proteins during the epithelial transformation of the developing liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:8419–8424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayhurst GP, Lee YH, Lambert G, Ward JM, Gonzalez FJ 2001. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (nuclear receptor 2A1) is essential for maintenance of hepatic gene expression and lipid homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol 21:1393–1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudling M, Parini P, Angelin B 1999. Effects of growth hormone on hepatic cholesterol metabolism. Lessons from studies in rats and humans. Growth Horm IGF Res 9: (Suppl A):1–7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Jiang S, Tanaka T, Iwanari H, Hotta H, Yamashita H, Kumakura J, Watanabe Y, Uchiyama Y, Aburatani H, Hamakubo T, Kodama T, Naito M 2003. Expression and localization of P1 promoter-driven hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α (HNF4α) isoforms in human and rats. Nucl Recept 1:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka T, Jiang S, Hotta H, Takano K, Iwanari H, Sumi K, Daigo K, Ohashi R, Sugai M, Ikegame C, Umezu H, Hirayama Y, Midorikawa Y, Hippo Y, Watanabe A, Uchiyama Y, Hasegawa G, Reid P, Aburatani H, Hamakubo T, Sakai J, Naito M, Kodama T 2006. Dysregulated expression of P1 and P2 promoter-driven hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α in the pathogenesis of human cancer. J Pathol 208:662–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Briancon N, Weiss MC 2006. In vivo role of the HNF4α AF-1 activation domain revealed by exon swapping. EMBO J 25:1253–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sladek FM, Ruse Jr MD, Nepomuceno L, Huang SM, Stallcup MR 1999. Modulation of transcriptional activation and coactivator interaction by a splicing variation in the F domain of nuclear receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α1. Mol Cell Biol 19:6509–6522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez JC, Ortiz JA, Hegardt FG, Haro D 1998. The hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (HNF-4) represses the mitochondrial HMG-CoA synthase gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 242:692–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chowdhury S, Gotoh T, Mori M, Takiguchi M 1996. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBP β) binds and activates while hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 (HNF-4) does not bind but represses the liver-type arginase promoter. Eur J Biochem 236:500–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nishiyama C, Hi R, Osada S, Osumi T 1998. Functional interactions between nuclear receptors recognizing a common sequence element, the direct repeat motif spaced by one nucleotide (DR-1). J Biochem (Tokyo) 123:1174–1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodenburg RJ 1996. Transcriptional regulation of the liver-specific promoter of the human IGF-II gene. Dissertation, University of Utrecht

- 51.Magenheim J, Hertz R, Berman I, Nousbeck J, Bar-Tana J 2005. Negative autoregulation of HNF-4α gene expression by HNF-4α1. Biochem J 388:325–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Briancon N, Bailly A, Clotman F, Jacquemin P, Lemaigre FP, Weiss MC 2004. Expression of the α7 isoform of hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF) 4 is activated by HNF6/OC-2 and HNF1 and repressed by HNF4α1 in the liver. J Biol Chem 279:33398–33408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rouet P, Raguenez G, Ruminy P, Salier JP 1998. An array of binding sites for hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 of high and low affinities modulates the liver-specific enhancer for the human α1-microglobulin/bikunin precursor. Biochem J 334:577–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salier JP, Rouet P, Raguenez G, Daveau M 1996. The inter-α-inhibitor family: from structure to regulation. Biochem J 315:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bailly A, Torres-Padilla ME, Tinel AP, Weiss MC 2001. An enhancer element 6 kb upstream of the mouse HNF4α1 promoter is activated by glucocorticoids and liver-enriched transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res 29:3495–3505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michalopoulos GK, Bowen WC, Mule K, Luo J 2003. HGF-, EGF-, and dexamethasone-induced gene expression patterns during formation of tissue in hepatic organoid cultures. Gene Expr 11:55–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jump DB 2004. Fatty acid regulation of gene transcription. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 41:41–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hertz R, Kalderon B, Byk T, Berman I, Za’tara G, Mayer R, Bar-Tana J 2005. Thioesterase activity and acyl-CoA/fatty acid cross-talk of hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α. J Biol Chem 280:24451–24461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duda K, Chi YI, Shoelson SE 2004. Structural basis for HNF-4α activation by ligand and coactivator binding. J Biol Chem 279:23311–23316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oyadomari S, Matsuno F, Chowdhury S, Kimura T, Iwase K, Araki E, Shichiri M, Mori M, Takiguchi M 2000. The gene for hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)-4α is activated by glucocorticoids and glucagon, and repressed by insulin in rat liver. FEBS Lett 478:141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reddy AB, Maywood ES, Karp NA, King VM, Inoue Y, Gonzalez FJ, Lilley KS, Kyriacou CP, Hastings MH 2007. Glucocorticoid signaling synchronizes the liver circadian transcriptome. Hepatology 45:1478–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li J, Gilmour RS, Saunders JC, Dauncey MJ, Fowden AL 1999. Activation of the adult mode of ovine growth hormone receptor gene expression by cortisol during late fetal development. FASEB J 13:545–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hyatt MA, Budge H, Walker D, Stephenson T, Symonds ME 2007. Ontogeny and nutritional programming of the hepatic growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor-prolactin axis in the sheep. Endocrinology 148:4754–4760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodenburg RJ, Teertstra W, Holthuizen PE, Sussenbach JS 1995. Postnatal liver-specific expression of human insulin-like growth factor-II is highly stimulated by the transcriptional activators liver-enriched activating protein and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-α. Mol Endocrinol 9:424–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Metzger S, Halaas JL, Breslow JL, Sladek FM 1993. Orphan receptor HNF-4 and bZip protein C/EBP α bind to overlapping regions of the apolipoprotein B gene promoter and synergistically activate transcription. J Biol Chem 268:16831–16838 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Birkenmeier EH, Gwynn B, Howard S, Jerry J, Gordon JI, Landschulz WH, McKnight SL 1989. Tissue-specific expression, developmental regulation, and genetic mapping of the gene encoding CCAAT/enhancer binding protein. Genes Dev 3:1146–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwartzbauer G, Yu JH, Cheng H, Menon RK 1998. Transcription factor MSY-1 regulates expression of the murine growth hormone receptor gene. J Biol Chem 273:24760–24769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]