Introduction

KEY TEACHING POINTS

|

The head-up tilt test (HUTT) is a useful diagnostic tool for evaluating suspected neurocardiogenic syncope. Pharmacologic provocation with isoproterenol, adenosine, or nitroglycerin (NTG) is frequently used to facilitate the induction of syncope during HUTT.1, 2 Studies have reported the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias during HUTT, especially with high-dose isoprenaline infusion in patients with structural heart disease.3, 4

Case report

A 55-year-old diabetic and hypertensive man presented with 3 episodes of syncope, all in upright posture, in the previous 1 and half years. He denied a history of angina, palpitation, or dyspnea at any time, including prior to the episodes. The patient was hospitalized after each episode and his vital signs, electrocardiogram, and blood sugars were found to be normal. He had no postural fall in blood pressure, carotids were normal, and no evidence of carotid hypersensitivity was noted. Echocardiogram was normal and Holter monitoring did not reveal any significant pause or arrhythmia. With the possibility of neurocardiogenic syncope, HUTT was performed using the Italian protocol.2 Briefly, the procedure was performed in the morning, after overnight fasting in a quiet, slightly darkened room that had resuscitative equipment, and was monitored by a cardiology resident and staff nurse. The tilt test was performed by means of an electronically controlled tilt table with a footboard for weight bearing. Restraining belts were placed at chest and thigh levels. Blood pressure, heart rate, and rhythm were continuously monitored using limb lead 2, and were recorded every 2−5 minutes, or more often if symptoms developed. Head-up tilt was performed after an initial observation with the patient in the supine position for 10 minutes. The test consisted of 2 consecutive phases; during the first phase, the patient was tilted at 60 degrees for up to 45 minutes without medication. Since baseline tilt did not induce syncope, the second phase of the test was repeated with the patient being tilted to 60 degrees after 300 mcg of sublingual NTG. After 5 minutes of upright tilt, the patient developed syncope, associated with abrupt sinus pause that continued for 9 seconds (Figure 1A and B), and as the patient was being lowered to supine position this was followed by a brief episode of ventricular fibrillation (VF) (Figure 1C). While the defibrillator was being readied to deliver a DC shock, external cardiac massage was being instituted and the VF terminated without the necessity of a DC shock (Figure 1D), first for a brief period of asystole followed by resumption of sinus rhythm. Subsequently, a treadmill test was performed on Bruce protocol to evaluate for coronary artery disease, which was strongly positive for inducible ischemia at 4 minutes of exercise, with no angina during the test. Coronary angiogram was performed and revealed triple vessel coronary artery disease (Figure 2A−D), for which the patient underwent successful coronary artery bypass surgery. At 2 months postsurgery, the patient underwent a repeat tilt table test, but this time with a hands-free defibrillator with external pacing capability applied to the chest wall. The test was positive, with an asystolic response of 6 seconds with no episode of VF. It was decided to manage the patient with conservative therapy with lifestyle modification and consider pacing if there were frequent recurrences of syncope. At 3 months postsurgery the patient has been free of syncopal episodes. Since the patient had a reversible cause of VF and normal ventricular function, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was not considered.

Figure 1.

A−D: Continuous tracing of lead II during head-up tilt test. Panel A shows gradual bradycardia followed by asystole that continues for 9 seconds (B); this is followed by the onset of ventricular fibrillation (VF) (C) and external cardiac massage is initiated.Thin arrows mark QRS complexes within the artifacts related to cardiac massage and (D) sinus rhythm resumes. CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

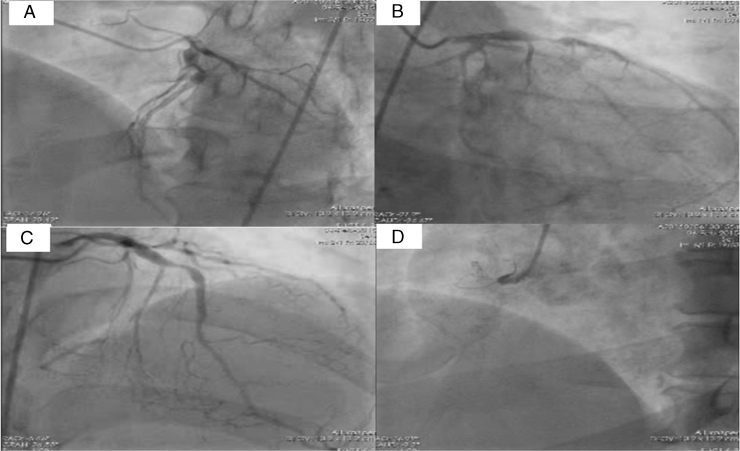

Figure 2.

Coronary angiogram in A: left anterior oblique cranial, B: right anterior oblique caudal, and C: cranial views showing significant lesions in proximal left anterior descending artery. D: The right coronary artery was totally occluded at the proximal segment.

Discussion

Head-up tilt test is a commonly used diagnostic tool for evaluating suspected neurocardiogenic syncope. During HUTT, if passive tilt does not induce syncope, isoprenaline, adenosine, and NTG are the pharmacologic agents used to facilitate the induction of syncope.1, 2, 5 A shortened oral NTG test and low-dose isoproterenol test are the most accurate head-up tilt protocols for this purpose, and their use has been recently recommended by the Task Force on Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology.6 Incidence of VF with HUTT is extremely rare (0.04%) and has occurred with high-dose (5 μg/min) isoprenaline infusion in patients with either undiagnosed underlying significant coronary artery disease, known structural heat disease, or apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.3, 4, 7 VF has not been reported with the use of NTG. In the present case the mechanism of VF can only be postulated. NTG acts as a provocative agent during tilt testing because of its potent vasodilator effects on the capacity vessels, causing venous pooling, enhanced by upright posture. It is likely that the prolonged asystole resulted in regional myocardial ischemia in the presence of significant coronary artery disease. Whenever there is abrupt and prolonged arrest of flow to the myocardium, it deprives ventricular myocytes of oxygen, causing rapid inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation and a switch to anaerobic glycolysis for production of high-energy phosphates. This transition has several important consequences and results in steep gradients of metabolic, ionic, and neurogenic changes specially to be present at the ischemic boundaries. Catecholamines released locally in ischemic myocardium contribute to the changes in electrophysiologic parameters during ischemia and play a role in the susceptibility of hearts to VF during regional ischemia.8 It is quite likely that NTG itself is not responsible for ventricular tachyarrhythmia. The termination of VF in the present case was possibly spontaneous. Spontaneous termination of VF, though rare, has been reported before.9

It is interesting to note that there has been no incidence of ventricular arrhythmias reported in a large study in the absence of provocative agents.7 It has been reported that as many as 35% of patients with syncope and structural heart disease have neurally mediated syncope, and it may be necessary to perform a tilt test as part of the evaluation of patients with structural heart disease.4 Most cases of VF during HUTT have occurred in patients with significant underlying coronary artery disease and reversible ischemia.3, 4 It is advisible to rule out reversible ischemia prior to HUTT in patients with risk factors and/or structural heart disease. In patients with structural heart disease, if HUTT is to be performed after ruling out reversible ischemia, it is prudent to avoid high-dose isoprenaline and to use a hands-free defibrillator while performing the test.

The incidence of ventricular asystole during spontaneous neurocardiogenic syncope does not imply a poor prognosis in terms of syncopal recurrences or sudden death.10 Ventricular asystole observed during HUTT, even when prolonged, is usually not indicative of a more advanced disease and/or serious future clinical events, such as frequent syncopal recurrences, important syncope-related injuries, and sudden death. Implantation of a pacemaker or drug treatment in patients with asystolic response is not associated with a lower syncopal rate during the follow-up.11 Hence it is suggested that an aggressive treatment with pacemaker should not be the standard therapy for all tilt-induced asystole, but should be reserved only for selected cases, on a single-patient basis.10 In the present case we did not offer pacemaker therapy but will continue to monitor the patient. The patient was also not offered an ICD, as the guidelines do not support the use of ICDs in reversible causes of VF and normal ventricular function.12 To the best of our knowledge, occurrence of VF during HUTT with NTG challenge has not been reported previously in the literature. It is also recommended that nitrates in the form of sublingual tablets or spray be avoided in patients with ischemic heart disease and history of syncope. HUTT should be avoided in patients with reversible ischemia, and if it needs to be done at all, it should be performed with due care after complete revascularization.

References

- 1.Natale A., Akhtar M., Jazayeri M., Dhala A., Blanck Z., Deshpande S., Krebs A., Sra J.S. Provocation of hypotension during head-up tilt testing in subjects with no history of syncope or presyncope. Circulation. 1995;92(1):54–58. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raviele A., Menozzi C., Brignole M., Gasparini G., Alboni P., Musso G., Lolli G., Oddone D., Dinelli M., Mureddu R. Value of head-up tilt testing potentiated with sublingual nitroglycerin to assess the origin of unexplained syncope. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(4):267–272. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leman R.B., Clarke E., Gillette P. Significant complications can occur with ischemic heart disease and tilt table testing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1999;22(4 I):675–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1999.tb00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheldon R., Rose S., Koshman M.L. Isoproterenol tilt-table testing in patients with syncope and structural heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78(6):700–703. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mittal S., Stein K.M., Markowitz S.M., Slotwiner D.J., Rohatgi S., Lerman B.B. Induction of neurally mediated syncope with adenosine. Circulation. 1999;99(10):1318–1324. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.10.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brignole M., Alboni P., Benditt D.G. Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncope - update 2004. Europace. 2004;6(6):467–537. doi: 10.1016/j.eupc.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim P.H., Ahn S.J., Kim J.S. Frequency of arrhythmic events during head-up tilt testing in patients with suspected neurocardiogenic syncope or presyncope. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(12):1491–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mustafa M.U., Baker C.S., Stephens J.D. Spontaneously terminating ventricular fibrillation and asystole induced by silent ischaemia causing recurrent syncope. Heart. 1998;80(1):86–88. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cascio W.E. Myocardial ischemia: what factors determine arrhythmogenesis? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12(6):726–729. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raviele A. Tilt-induced asystole: a useful prognostic marker or clinically unrelevant finding? Eur Heart J. 2002;23(6):433–437. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barón-Esquivias G., Pedrote A., Cayuela A., Valle J.I., Fernández J.M., Arana E., Fernández M., Morales F., Burgos J., Martínez-Rubio A. Long-term outcome of patients with asystole induced by head-up tilt test. Eur Heart J. 2002;23(6):483–489. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein A.E., DiMarco J.P., Ellenbogen K. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices) developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(21):e1–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]