Abstract

Background and Objectives

Although interest in assessing risk of TTIs, very few trends in blood safety epidemiological data from resource-limited blood services are reported in the literature. This analysis aims at reporting trends in seroprevalences of TTIs in blood donations in the Yaoundé University Teaching Hospital (UTH) from 2011 to 2015 and to describe reasons for these changes.

Materials and Methods

All donations of 2015 were tested for HIV 1&2 antibodies and the P24 antigen, HBsAg, HCV antibody and the Treponema pallidum antibody. Screening for HIV uses a national algorithm based on the systematic use of two assays of different principles: a rapid determination testing assay and an EIA HIV 1 & 2 Ab-Ag. The tests used for HBsAg and HCVAb screening were all based on EIA techniques. Treponema pallidum antibody screening was based on Treponema Pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA) and rapid immunochromatographic test (RIT). Screening techniques and results from 2015 were compared to retrospective data from 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014.

Results

In 2015, 13·4% (n = 214) of 1,596 blood donations were seropositive for at least one screened TTIs. The most frequent serological marker was HBsAg with 123 (7·7%) blood units contaminated. Nineteen (1·2%) and 18 (1·1%) blood units was positive for HIV and syphilis, respectively. There was a significant decrease in the total number of blood donations (P < 10−4) and HIV, HBsAg and syphilis seroprevalences and an increase in the proportion of voluntary non-remunerated blood donor (P < 0·05). HCVAb seroprevalence was 3·8% in 2015 and has not decreased significantly over the years (P = 0·09).

Conclusion

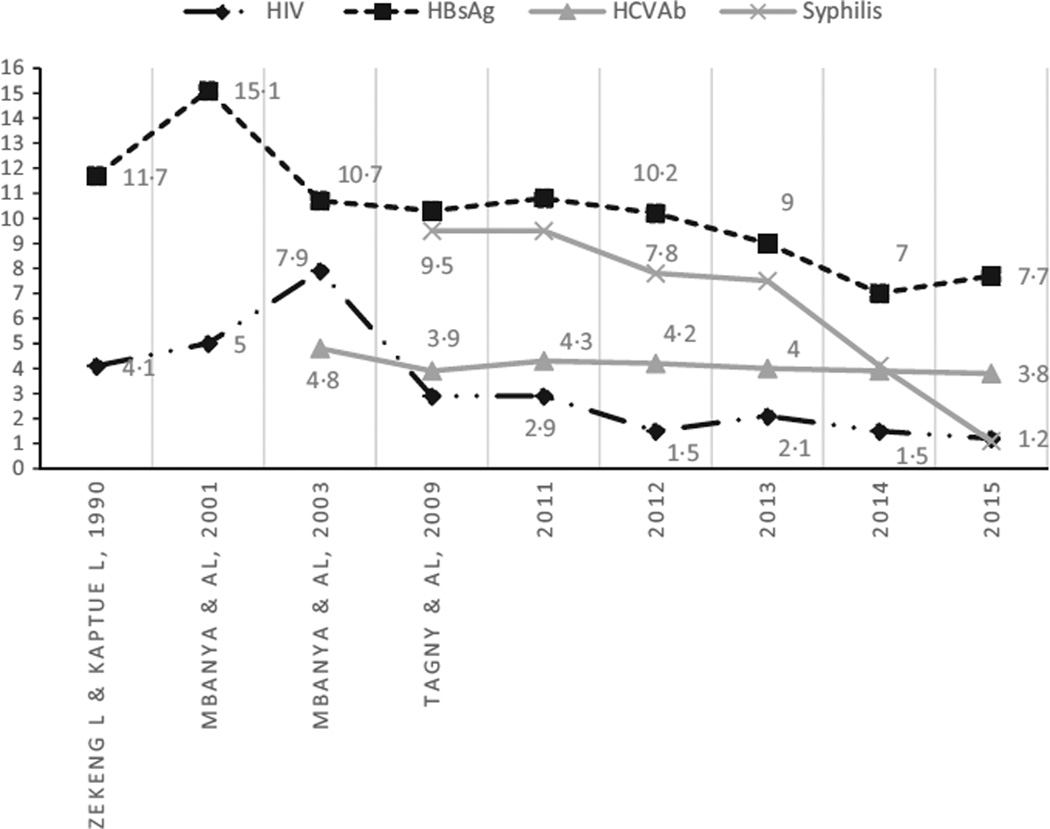

Significant progress is noted in reduction in seroprevalences of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis since the beginning of a regular registration of data in 1990.

Keywords: blood donation, Cameroun Africa, transfusion-transmitted infections

Introduction

In the 1990s, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection pandemic was at its highest level of morbidity and mortality in Cameroon and the national programme in charge of AIDS control and blood safety was still in early stages. At that time, only HIV 1 & 2 antibodies and the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) were screened for in blood donations by a few trained staff [1]. The seroprevalences of transfusion-transmitted infections (TTIs) have been reported in Cameroon and other African countries to be high [2]. Despite significant a decrease during the following years, HIV seroprevalence remains high in the general population of Cameroon. In 2004, the HIV seroprevalence was 5·5% in the age group of 19–45 years and 6·8% in women compared with 4·1% in men [3]. In 2015, there was an estimated 4·2% seroprevalence in the age group of 19–45 years [4]. No formal strategic plan in blood safety at the national level is currently fully implemented. Indeed, blood safety activities are still implemented by blood banks and hospitals that host them with an irregular support from the national programme.

The Hematology and Blood Transfusion Service of the Yaoundé University Teaching Hospital (UTH) has a hospital-based blood bank that functions under administrative and medical authority of a Hospital executive office. In the 1990s, the proportion of contaminated blood units by the 4 main TTIs (HIV, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and syphilis) was 15–20% with a seroprevalence (based on screening tests only) of HIV antibodies and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in blood donation of 4·1% and 10–15%, respectively [1].

Although interest in assessing risk of TTIs in the blood bank started at its inception, the regular follow-up of epidemiological data of blood safety was initiated only in 2000 in UTH by Mbanya & Tagny. The earliest trends were reported in 2005 that showed the critical role of voluntary non-remunerated blood donation (VNRBD) in the reduction in TTIs [5]. In 2011, the Hematology and Blood Transfusion Service of the UTH implemented a set of blood safety activities that will help the service to improve quality in a stepwise manner towards a possible accreditation by the WHO, the African Society of Laboratory Medicine (ASLM) or the African Society of Blood Transfusion (AfSBT). This analysis aims at reporting trends in seroprevalences of TTIs in blood donations in the UTH from 2011 to 2015 and to describe reasons for these changes.

Materials and methods

We compared current data from 2015 to historical data from 2011 to 2014. Before collecting blood from each donor, demographic data including age and sex were obtained from the apparently healthy donors having fulfilled selection criteria including: weight >50 kg, age from 18 to 65 years, no infectious risk behaviour such as injection of illegal drugs or sex with somebody exposed to HIV risk since at least 4 months, and no blood donation since at least 3 months for male and 4 months for female.

Donations were identified and classified as either first-time, lapsed or repeat, or benevolent or family/replacement donation. Since 2015, all donations are tested for HIV 1&2 antibodies and the P24 antigen, HBsAg, HCV antibody and the Treponema pallidum antibody. Screening for HIV in the UTH uses a national algorithm based on the systematic use of two assays of different principles: a rapid determination testing assay (Determine HIV-1/2, Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA) and an EIA HIV 1&2 Ab-Ag (Murex HIV Ag/Ab, DiaSorin SpA, Saluggia, Italy). Results are reported as HIV seropositive when reactive to the 2 different HIV 1&2 assays. In case of emergency, two different rapid diagnostic assays are used, the first being Determine HIV-1/2 and the second one the discriminatory Immunocomb, HIV 1&2 BiSpot (Orgenics, Courbevoie, France). All samples that are non-reactive with the two assays are reported HIV negative, while doubtful samples are reactive twice for only one assay. The tests used for HBsAg and HCVAb screening are all based on EIA techniques (Genedia HBsAg ELISA 3.0, Green Cross Life Science Corp, US and Innotest HCV Ab III, Innogenetics, US). In the UTH since 2014, Treponema pallidum antibody screening is based on two different techniques: Treponema Pallidum hemmaglutination assay (TPHA) (Cypress Diagnostics, Hulshout, Belgium) and rapid immunochromatographic test (RIT) (Determine Syphilis, Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA). Syphilis seropositive samples are samples that are reactive to both techniques. Seronegative samples are non-reactive to either assay, while doubtful samples are reactive twice to only one technique. All reactive or doubtful donations are discarded. For all doubtful results, blood donors were requested to come back for another screening within 1–3 months or to perform confirmation testing in a reference laboratory. In any case, doubtful results were excluded from the present analysis because data of the third confirmatory test performed in another facility were frequently not available. Thus, the seroprevalences of TTIs have been calculated on the basis of seropositive results obtained at the screening as described above. All screening assays selected and used in the UTH blood bank were WHO-approved with a reported manufacturer sensitivity higher than 99% and specificity higher than 98%. Results from 2015 were compared to retrospective data from 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014. Historical screening techniques of HIV, HCV, HBV and syphilis were different from that of 2014 and 2015 and have been reported in Results section for comparison.

The trends in the seroprevalence of the various infections over the years were assessed using the chi-square for trends [6]. Seroprevalences were considered statistically different for a P -value<0·05.

Results

From the 1 January to 31 December 2015, the UTH blood bank collected and tested 1,704 blood units among which 108 (6·3%) had doubtful results because HIV or syphilis testing results were discordant twice.

A total number of 1,596 blood donations were then included in this study. Donations from male blood donors represented 82·3% (n = 1313) for a male-to-female ratio of 4·6/1. The blood donor ages ranged from 16 to 59 years with a mean of 29 ± 11 years. Family/replacement blood donations represented 74·7% (n = 1193), while voluntary non-remunerated blood donations (VNRBDs) represented 25·3% (n = 403). Among the VNRBD, 38 (2·4%) were regular and 19 (1·2%) were lapsed donations. In 2015, 13·4% (n = 214) of blood donations were seropositive for at least one screened TTIs. The most frequent serological marker was HBsAg with 123 (7·7%) positive donations. Nineteen (1·2%), 18 (1·1%) and 61 (3·8%) blood units were positive for HIV and syphilis, respectively (Table 1). Family/replacement blood donations had a higher proportion of positive blood units.

Table 1.

TTI screening results among blood donations in 2015

| n = 1596 | % | Total contaminated n = 214 |

HIV (% positive)a n = 19 |

Ag HBs (% positive) a n = 123 |

HCV (%positive)a n = 61 |

Syphilis (%positive) a n = 18 |

Co-infections n = 7 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VNRBD | FTD | 390 | 24·4 | 30 | 2 | 18 | 12 | 0 | 2 |

| RD | 8 | 0·5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| LD | 5 | 0·3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 403 | 25·2 | 34 | 3 (0·7) | 18 (4·4) | 13 (3·2) | 2 (0·4) | 2 | |

| FRD | FTD | 1149 | 72 | 175 | 16 | 105 | 48 | 11 | 5 |

| RD | 30 | 1·8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | |

| LD | 14 | 0·8 | 0 | 0 | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0 (0) | 0 | |

| Total | 1193 | 74·8 | 180 | 16 (1·3) | 105 (8·8) | 48 (4·0) | 16 (1·3) | 5 |

FTD: First-time donation; RD: regular donation; LD: lapsed donation; FRD: family replacement donation; VNRBD: Voluntary non-remunerated blood donation.

Row percentage.

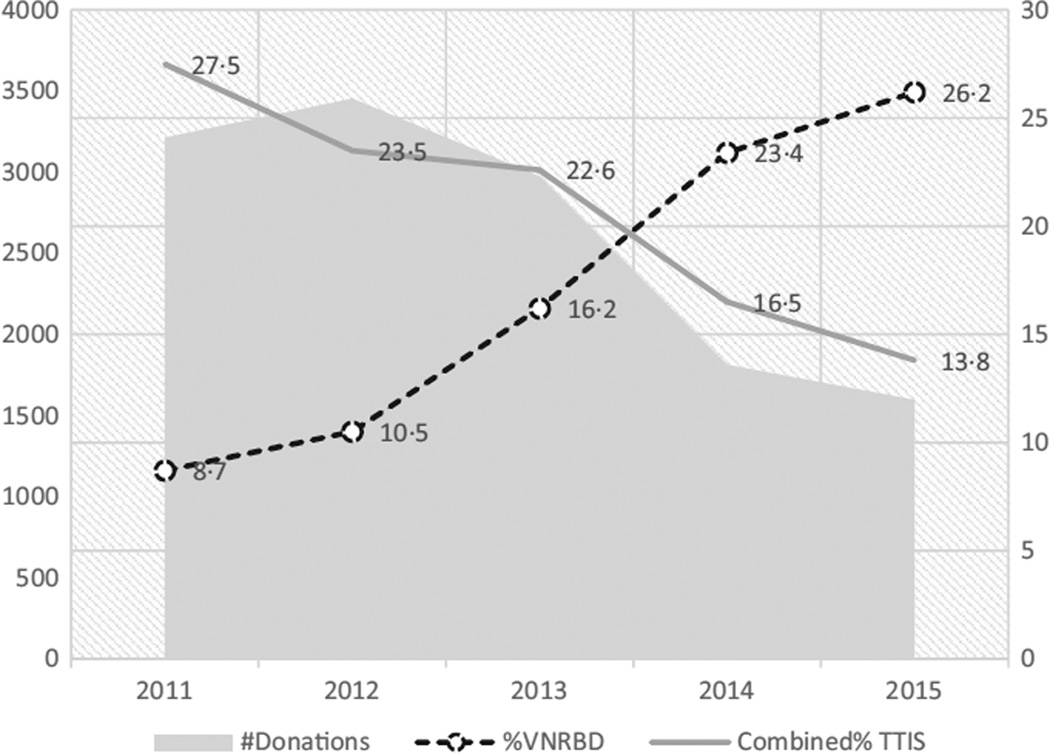

The total number of blood donations excluding doubtful TTI results was 3,213, 3,455, 2,974, and 1,813 in 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014, respectively. The proportion of VNRBD was 8·67% in 2011 and 23·4% in 2014.

Serological findings from 2011 and 2015 are reported in Table 2. There is a significant decrease in the total number of blood donations (P < 10−4) and HIV, HBsAg and syphilis seroprevalences and an increase in the proportion of VNRBD (P < 0·05). HCVAb seroprevalence has not decreased significantly over the years (P = 0·09).

Table 2.

Screening results among blood donors from 2011 to 2015

| Years | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donationsa | Total | 3213 | 3455 | 2974 | 1813 | 1596 | |

| HIV | Screening method | RDT +EIAAb | RDT +EIAAg-Ab | RDT +EIAAg-Ab | RDT +EIAAg-Ab | RDT +EIAAg-Ab | |

| Seropositivity n (%) | 94 (2·9) | 53 (1·5) | 64 (2·1) | 49 (1·5) | 19 (1·2) | 0·005 | |

| HBs Ag | Screening method | RDT or EIA Ag | RDT or EIA Ag | EIA Ag | EIA Ag | EIA Ag | |

| Seropositivity n (%) | 347 (10·8) | 343 (10·2) | 358 (9) | 127 (7) | 123 (7·7) | 0·001 | |

| HCV Ab | Screening method | RDT or EIA Ab | RDT or EIA Ab | EIA Ab | EIA Ab | EIA Ab | |

| Seropositivity n (%) | 139 (4·3) | 138 (4) | 119 (4) | 71 (3·9) | 61(3·8) | 0·09 | |

| Syphilis | Screening method | RPR +TPHA | RPR + TPHA | RPR +TPHA | TPHA +RIT | TPHA +RIT | |

| Seropositivity n (%) | 306 (9·5) | 270 (7·8) | 223(7·5) | 75(4·1) | 18 (1·1) | 0·005 |

Donations with doubtful TTI testing results are excluded in the number.

The trends of combined TTI seroprevalences from 2011 to 2015 are compared to corresponding trends of number of blood donations and proportion of VNRBD (Fig. 1). The combined TTI seroprevalence is decreasing, while the proportion of VNRBD is increasing.

Fig. 1.

Trends in combined TTI seroprevalence, number of blood donation and proportion of VNRBD.  : Number of donations;

: Number of donations;  : Percentage of voluntary non-remunerated blood donations;

: Percentage of voluntary non-remunerated blood donations;  : Combined percentage of transfusion-transmitted Infections.

: Combined percentage of transfusion-transmitted Infections.

The trends in TTI seroprevalence that compare present to past data in the same institution are provided above (Fig. 1). HBV, HIV and syphilis seemed to significantly decrease among blood donors since 1990. HCV Ab seroprevalence has slowly decreased from 4·8% to 3·8% in 22 years (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Trends in TTI seroprevalence among blood donors of UTH since 1990.  : Seroprevalence of HIV;

: Seroprevalence of HIV;  : Seroprevalence of AgHBs;

: Seroprevalence of AgHBs;  : Seroprevalence of HCV Antibody;

: Seroprevalence of HCV Antibody;  : Seroprevalence of syphilis Antibody.

: Seroprevalence of syphilis Antibody.

Discussion

Findings of these trends revealed a significant decrease in total number of blood collections at UTH since 2011, but a slight improvement in blood collection from VNRBD. Significant progress is noted in reduction in seroprevalences of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis since the beginning of a regular registration of data in 1990.

This decrease in total number of blood collections and the low rate of regular blood donation are probably due to lack of full implementation of the existing educational, motivational and recruitment plans. Indeed, as a hospital-based blood bank, the UTH has a limited budget that is not autonomous, and completely dependent on the Hospital’s administration. Blood donor education, motivation, recruitment and repeat donation strategies like sensitization campaigns and phone calls are not regularly implemented. Furthermore, incentives such as small gifts or taxi fares are not available.

Due to some financing from the new National Blood Transfusion program of Cameroon, in 2013, a blood collection plan was implemented by the UTH which increased the number of mobile blood drives in universities, schools and churches, with increased recruitment of VNRBD. Increase in VNRBD rate could also be explained by reinforcement of conversion of family/replacement donors to VNRBD. The creation an enabling environment for 100% voluntary non-remunerated blood donation needs sufficient and sustainable financial means as recruitment, retention and collection is one of the most expensive step of the blood safety value chain [7].

The detection of TTIs has greatly improved in Africa during the past decade [2] and particularly at UTH of Yaoundé [8–10]. However, residual risk is still very high [11]. The efficacy of screening tests are still limited due to many reasons such as genetic variations, inappropriate or incomplete quality assurance programmes in many centres and the inability to detect recently infected subjects. The lower sensitivity of HIV 1&2 RDT and EIA Ab testing used in 2011 compared with EIA Ab-Ag implemented since 2012 has been demonstrated in the setting [12]. The HIV seroprevalence in 2011 may have been underestimated in donors with indeterminate or negative results due to the low quality of assays, which may have missed low-titre HIV infections. The study demonstrated that the high sensitivity of HIV Ag-Ab assay would allow the prevention of 55 HIV transmissions in 10,000 tested donations.

On the other hand, the replacement of Veneral Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test by a rapid immunochromatographic test (RIT) since 2014 in Treponema pallidum antibody screening could explain the rapid drop in the seroprevalence of syphilis. A reported low specificity of RPR in the same setting has underestimated the seroprevalence due to numerous false-positive results related to other treponemal infections [13].

The progress towards the reduced risk of TTIs could be explained by the higher proportion of VNRBD as VNRBD has lower prevalences of TTIs [5, 14]. This may have gradually reduced seroprevalences of TTIs in the UTH blood bank. Moreover, the UTH blood bank improved its donor medical screening strategy, which is reported to be very efficient in reduction in risk of TTIs [15, 16]. In 2011, the UTH blood bank attributed specific space for blood donor counselling and medical interviews, separate from blood donor collection areas. Indeed, confidentiality and comfort reduce risk of false responses during blood donor interview and may contribute to improve efficacy of this critical safety step [17,18]. Donor interviewing has since been standardized with specific staff appointed to manage the process. However, the questionnaire currently used in the blood bank since 2010 is still based on reported infectious risk in European and American surveys. Thanks to a grant from the AABB National Blood Foundation, a 2-year study has enabled the analysis in the blood bank of risk factors associated with HIV infection in our setting. This will help in developing an adapted questionnaire that takes into consideration some hitherto unrecognized TTI local risk factors.

If the decrease in TTI seroprevalence at the UTH is obvious, but truly positive donors are still to be determined. Indeed, no confirmatory strategies are routinely used. For instance, we have shown in 2011 that prevalence of HCV infection dropped from 4·3% on the basis of screening results only to 1·8–2·8% when immunoblot testing and/or RNA detection was performed [19]. Numerous false-positive results due to lack of specificity of EIA screening tests and resolved or inconclusive infections (HCV Antibodies) explained the differences. Hence, ‘true’ prevalences in the UTH blood bank are probably lower than currently reported. On the other hand, the partial use of rapid determination testing in UTH blood bank before 2013 could have led to underestimated seroprevalence of HBsAg in particular, since screening sensitivity of this type of reagent have been clearly reported to be lower than 0·8 in numerous blood centres in sub-Saharan countries [20].

Since 2011, the Hematology and Blood bank of the UTH has implemented a set of blood safety activities that have enabled the service to improve its level of quality in a stepwise manner towards a possible accreditation by WHO, African Society of Laboratory Medicine (ASLM) or African Society of Blood Transfusion (AfSBT). The following activities have been conducted: (i) Implementation of a Quality Management System through a WHO stepwise quality improvement program called ‘SLMTA” (Strengthening of Laboratory Management Towards Accreditation), (ii) increase in the proportion of regular blood donor, (iii) review and process improvement in the blood donor interview, (iv) training of staff in medical selection of blood donor and TTI screening.

Participation in the SLMTA programme has raised awareness of a safer blood. The standardization of donor screening processes in the UTH through development and implementation of SOPs, formal instructions, appropriate registers and record sheets has set-up harmonized practices that are now easily followed up by all the staff. The implementation of quality system and haemovigilance activities has already been positively experienced in terms of reducing risks of TTIs in Africa [21, 22]. Currently, the AfSBT stepwise accreditation is more appropriate to blood transfusion services and has started to be implemented in some African countries. The UTH is not yet involved with this.

An in-house training programme has been implemented in the service since 2011. Recently, The Safe Blood for Africa Foundation (SBFA), in collaboration with the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), PEPFAR and the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) of Cameroon, as part of a programme for enhancing blood safety in Cameroon, organized a training programme on TTIs [23]. The aim of the five-day course was to impart blood bank technical staff with basic knowledge and technical skills in TTIs and testing for these. Special emphasis was placed on HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis infections, which are mainly screened TTIs in transfusion medicine in Africa. The trained staff provided a feedback report to the rest of the team and were appointed in key safety areas such as donor and donation screenings areas.

The results of this study should encourage heads of hospital-based blood banks in African resource-limited countries. The challenge in the dropping proportion of contaminated blood from 13% to less than 5% by the year 2020 while keeping sufficient blood supply for the hospital has been set as the main blood safety objective at the Yaoundé UTH blood bank. This will never be achieved without strong administrative and technical support from the hospital executive office and the National Blood Transfusion Program. A formal strategic collaboration plan with the national programme and creation of a functional Hospital Transfusion and hemovigilance committee are the first steps for the new challenge.

Acknowledgments

CTT and AN contributed to research design, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data; CTT, AN, SL, EM and DM drafted the paper or revised it critically; CTT, AN, SL, EM and DM approved of the submitted and final versions.

References

- 1.Zekeng L, Kaptue L. Sérologie HIV et portage de l’antigène HBs et Hbe chez les donneurs de sang au CHU de Yaoundé. Cameroun. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1990;70:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apata IW, Averhoff F, Pitman J, et al. Progress toward prevention of transfusion-transmitted hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection–sub-Saharan Africa, 2000–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:613–619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institut National de la Statistique. Enquête Démographique et de Santé du Cameroun. Yaoundé, Cameroun: Ministère de l’administration territoriale; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comité National de Lutte contre le Sida. Profil des Estimations et projections en matière de VIH/sida au Cameroun. Yaoundé Cameroun: Ministère de la Sante Publique; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mbanya DN, Tagny CT. Blood safety begins with safe donations: update among blood donors in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Transfus Med. 2005;5:395–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2005.00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armitage P, Berry G. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2nd. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lara AM, Kandulu J, Chisuwo L, et al. Laboratory costs of a hospital-based blood transfusion service in Malawi. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1117–1120. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.042309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mbanya D, Binam F, Kaptue L. Transfusion outcome in a resource-limited setting of Cameroon: a five-year evaluation. Int J Infect Dis. 2001;5:70–73. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(01)90028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mbanya DN, Takam D, Ndumbe P. Serological findings among first-time blood donors in Yaoundé, Cameroon: is safe donation a reality or a myth? Transfus Med. 2003;13:1–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2003.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tagny CT, Diarra A, Yahaya R, et al. Characteristics of blood donors and donated blood in sub-Saharan Francophone Africa. Transfusion. 2009;49:1592–1599. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lefrère JJ, Dahourouh H, Dokekias AE, et al. Estimate of the residual risk of transfusion-transmitted human immunodeficiency virus infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a multinational collaborative study. Transfusion. 2011;51:486–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tagny CT, Mbanya D, Leballais L, et al. Reduction of HIV transfusion-transmitted infection risk by using a HIV Ag/Ab combination assay in blood donation screening in Cameroon. Transfusion. 2011;51:184–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tagny CT, NonoTagny O, Ngo Balogog P, et al. Performances of TPHA, RPR and rapid immuno-chromatographic test in syphilis screening among blood donors at the university teaching hospital of Yaoundé, Cameroon. Transfus Clin Biol. 2015;23(2):113–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tapko JB, Toure B, Sambo LG. Status of blood safety in the WHO African Region: report of the 2010 survey. Brazzaville: AFRO WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hussein E. Blood donor recruitment strategies and their impact on blood safety in Egypt. Transfus Apher Sci. 2014;50:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tagny CT, Kouao MD, Touré H, et al. Transfusion safety in Francophone African Countries: an analysis of strategies for the medical selection of blood donors. Transfusion. 2012;52:134–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agbovi KK, Kolou M, Fétéké L, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices about blood donation. A sociological study among the population of Lomé in Togo. Transfus Clin Biol. 2006;13:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olaiya MA, Alakija W, Ajala A, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and motivations towards blood donations among blood donors in Lagos, Nigeria. Transfus Med. 2004;14:13–17. doi: 10.1111/j.0958-7578.2004.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tagny CT, Mbanya D, Murphy EL, et al. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in a high prevalence country by an antigen/antibody combination assay versus a rapid test. J Virol Methods. 2014;199:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laperche S on behalf of the Francophone African Group for research in Blood Transfusion. Multi-assessment of blood-borne virus testing and transfusion safety on the African continent. Transfusion. 2013;53:816–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arewa OP. Improving supply of safe blood and reducing cost of transfusion service through haemovigilance. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2009;16:236–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouattara H, Siransy-Bogui L, Fretz C, et al. Residual risk of HIV, HVB and HCV transmission by blood transfusion between 2002 and 2004 at the Abidjan National Blood Transfusion Center. Transfus Clin Biol. 2006;13:242–245. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Safe Blood for Africa Foundation. The Safe Blood for Africa Foundation™. Rivonia, South Africa: 2014. Training in blood safety in Cameroon. Training plan: 2014–2018. [Google Scholar]