Synopsis

Despite being questioned as a survey measurement tool, self-reported age at marriage appeared valid in rural India, where a lack of birth records persists.

Keywords: Child marriage, India, Self-report validity

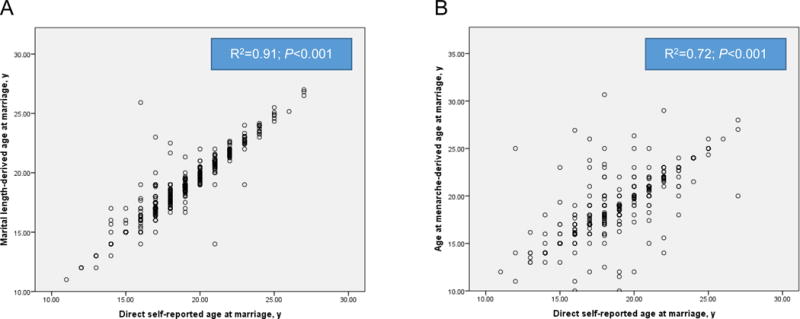

Worldwide, 15 million girls worldwide are married each year aged younger than 18 years, compromising their health and opportunities [1]. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include the target of ending child marriage by 2030. Birth registration is a priority to facilitate the identification of minors and achieve this target [2]; however, it is unlikely to help the large number of girls without birth records. Within India, which accounts for one-third of global child marriages [1], there are 71 million children younger than 5 years with unregistered births [2]. Less educated and impoverished girls from rural areas are the least likely to have a birth record [2] and the most likely to marry as minors [1]. Individuals’ self-reported age at marriage from household surveys forms the basis of measuring this SDG target. The validity of self-report age has been questioned [3] but research assessing the validity of self-reported age at marriage is lacking. As part of a larger survey of family planning in rural Maharashtra, India (study details elsewhere [4]), the present study assessed self-reported age at marriage and, as a validity check, age at marriage based on calculating: (1) subtracting the duration of marriage in months from the current age in years (marital length-derived age at marriage) and (2) current age minus months since menarche plus months from menarche to marriage (age at menarche-derived age at marriage). Data were collected using surveys applied by trained staff. Variables were dichotomized as child marriage (<18 y) or not, and married women aged 17–30 years were eligible to participate. Linear regressions and scatterplots were used to assess associations between direct self-reported age and each of the calculated age at marriage variables; calculations were performed using SPSS version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and P<0.05 was considered significant. There were 1081 participants included; the mean±SD marital length was 4.0±2.74 years and 321 (29.7%) participants had been married for no longer than 2 years. The mean length of time between menarche and marriage was 2.63±4.96 years. A majority of participants (735 [68.0%]) described themselves as being tribal (i.e. of an ethnic group with traditional practices and shared customary law) and 207 (19.1%) had no formal education. Child marriage was reported by 337 (31.2%) participants based on direct assessment, 385 (35.6%) based on marital length-derived calculation, and 346 (32.0%) based on the age at menarche-derived calculation. Both calculated variables were significantly associated with direct self-reported age (P<0.001), but a stronger correlation with self-reported age was observed for marital length-derived calculation (Figure 1). Based on these findings, it is suggested that self-reported age can offer a reliable measure for monitoring the child-marriage SDG target in settings where birth records are not available; further, the use of current age and marital duration questions, common to demographic surveys, can help validate direct self-reported age at marriage.

Figure 1.

Scatterplots comparing direct self-reported age at marriage with marital length-derived age at marriage and age at menarche-derived age at marriage (n=1081).

Acknowledgments

The present study was funded by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (#BT/IN/US/01/BD/2010) and the United States National Institute of Health (RO1HD61115).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.United Nations Children’s Fund. Ending Child Marriage: Progress and prospects. UNICEF; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Children’s Fund. Every Child’s Birth Right: Inequities and trends in birth registration. UNICEF; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neal SE, Hosegood V. How reliable are reports of early adolescent reproductive and sexual health events in Demographic and Health Surveys? Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2015 Dec;41(4):210–7. doi: 10.1363/4121015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raj A, Ghule M, Ritter J, Battala M, Gajanan V, Nair S, et al. Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluation of a Gender Equity and Family Planning Intervention for Married Men and Couples in Rural India. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(5):e0153190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]