Abstract

Purpose

To demonstrate the application of Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) for analyzing Schirmer strips for particle concentration, size, morphology, and type distribution.

Methods

A cross-sectional design was used. Patients were prospectively recruited from the Miami Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System eye clinic and underwent a complete ocular surface examination. Size, type and chemical composition of PM Schirmer strips (from the left eye) were analyzed using SEM/EDS.

Results

Schirmer strips from all six patients showed particle loading, ranging from 1 to 33 particles, while the blank Schirmer strip that served as a control showed no particle loading. The majority of particles were coarse, with an average size of 19.7 μm (95% confidence interval 15 μm to 24.4 μm). All samples contained organic particles (e.g. pollen and mold), and five of the six samples contained non-organic particles. The non-organic particles were composed of silicon, minerals, and metals including gold and titanium. The size of aluminum and iron particles was ≥ 62 μm, whereas the size of two other metals, zinc and gold, were smaller, i.e. < 20 μm. Most metal particles were elongated compared to the organic particles that were round.

Conclusion

Although SEM/EDS has been extensively used in biomedical research, its novel application to assess the size, morphology and chemical composition of the ocular surface particles, offers an unprecedented opportunity to tease out the role of PM exposure in the ocular surface disease and disorder.

Keywords: Ocular Surface, Particulate Matter (PM), SEM, EDS, Dry Eye

INTRODUCTION

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS) are well-established techniques that have extensively been used in biomedical research, including biological (such as cells, bacteria and viruses) and characterization of particulate matter (PM) samples.1–3 A systematic review of the applications of SEM/EDS is provided in the Supplementary Online Material (SOM) (Table S1). Although adverse effects of PM in cardiopulmonary disease have been subject to intensive research scrutiny, little research is available on the role of PM in the ocular surface disease. This paper provides a novel application of SEM/EDS to study the ocular surface PM, which can play an important role in ocular surface diseases and disorders 4.

We are constantly exposed to airborne particulate matter (PM) through inhalation, ingestion, dermal contact, and ocular surface contact. PM exposure can lead to oxidative stress, which can activate innate responses and a downstream cascade of biophysiological changes including inflammation and lipid peroxidation.5–8 Most research has focused on understanding the relationship between short- and long-term PM exposure and cardiopulmonary disease.9,10 For example, PM exposure is implicated in reduced lung-function, asthma and stroke.11–13 However, knowledge of the effects of PM on the cardiopulmonary system cannot be directly extrapolated to other disease, such as disease of the ocular surface, because of differing anatomy and physiology. First, in cardiopulmonary disease, airways and circulatory systems are constantly exposed to PM through inhalation. Fine particles, ≤ 2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter, can reach the alveoli and become part of circulatory system, while large particles, > 2.5 μm and ≤10 μm, are deposited in the airways. Conversely, particles, especially of large sizes, can remain on and affect the health of the ocular surface, and small particles may reach conjunctival vessels though at a slower rate than in airways. Second, mechanisms by which PM affect ocular surface cells are potentially different than in cardiopulmonary disease. For example, PM loading (depending on particle size) can cause abrasions (through blinking and rubbing eyes) on the ocular surface in addition to oxidative stress, which does not happen in the airways.4 Exposure to PM (depending on chemical composition) can alter the lipid profile of tears, directly affecting the stability of the tear film.14 Furthermore, unlike airways that are covered with a thick layer of mucosa, the ocular surface is covered with a thin tear film. Therefore, scavenging, deposition, and penetration mechanisms of PM are likely to be different across airway and ocular surfaces. Finally, exposure time differs as the ocular surface is exposed to PM only during waking hours while PM exposure in the lung occurs day and night. While eyes are closed new PM exposure does not take place. However, PM previously trapped on the ocular surface may continue causing oxidative stress.

Based on biologic plausibility, it is not surprising that epidemiological studies have found significant association between elevated PM exposure and dry eye.4,15,16 These studies have been limited to measuring total PM mass without analyzing specific particle information. Toxicity of PM, however, is not uniform and largely depends on characteristics including concentration, size distribution, chemical composition, and particle morphology.17 A precise understanding of particle concentration, size and type distribution on the ocular surface is critical to evaluate the effects of PM exposure on the ocular surface. The goal of this paper is to present a methodology to characterize PM loading, type, shape and size distribution on the ocular surface using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS).

METHODS AND MATERIALS

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with the requirements of the United States Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and was approved by the Miami VA Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

Six patients without overt eyelid or corneal abnormalities were recruited from the Miami Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System eye clinic, and underwent a complete ocular surface examination. Exclusion criteria included contact lens use, history of refractive surgery, ocular medications with the exception of artificial tears, an active external ocular process, cataract surgery within the last 6 months, or any glaucoma or retinal surgery in the past. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Data Collection

Patients completed survey questions and underwent an ocular surface exam of both eyes, which included: 1) measurement of tear breakup time (TBUT) (5 μl fluorescein placed, 3 measurements taken in each eye and averaged); 2) measurement of corneal epithelial cell disruption via corneal staining (National Eye Institute (NEI) scale,18 5 areas of cornea assessed; score 0–3 in each, 15 total); 3) Schirmer’s test using Schirmer strips with anesthesia.

SEM/EDS Protocol

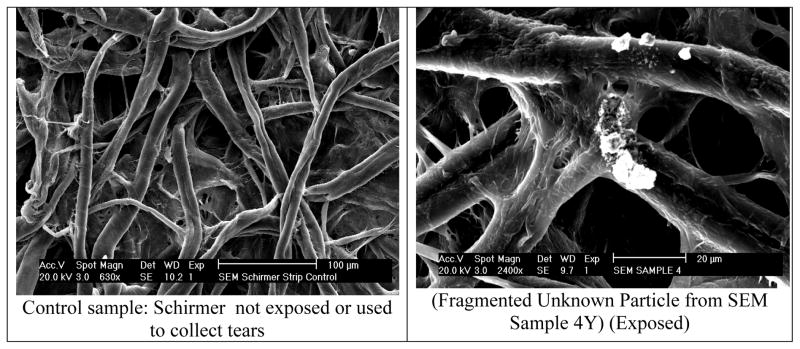

To prepare samples for analysis, the 5 mm round tip of the Schirmer strip that contacted the ocular surface was cut and placed on a metallic SEM/EDS stub under a vacuum hood. The metallic stubs were covered with an adhesive carbon film to provide a suitable field for analysis. All samples were coated with palladium via sputter coating method to reduce microscope beam damage to the samples, increase thermal conduction, reduce sample charging, improve secondary electron emission, reduce beam penetration with improved edge resolution, and protect beam sensitive specimens.19,20 One unexposed (control) Schirmer strip was analyzed to understand the background structure of the strip (Figure 1a) and to establish a basis for comparison with the PM on Schirmer strips (Figure 1b). The coated samples were then mounted in the SEM/EDS device for follow-up analysis. The vacuum pump was first initiated for adequate filtration of the sample space. The electron beam was then turned on to begin viewing each sample.

Figure 1.

Control and exposed Schirmer strips under SEM.

Data Analysis

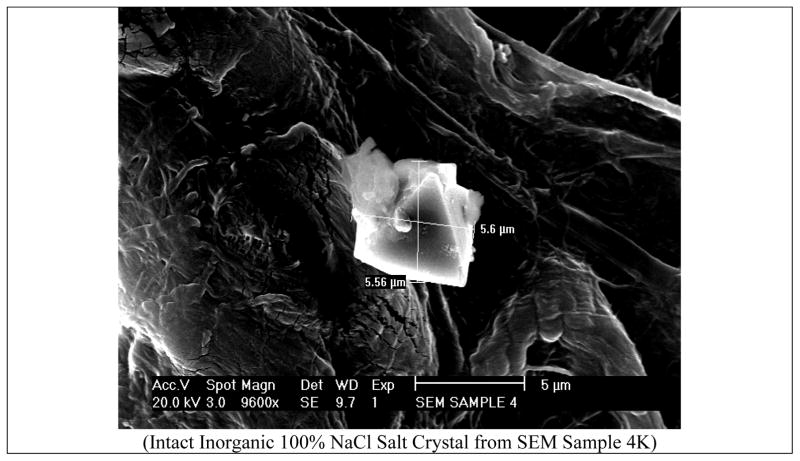

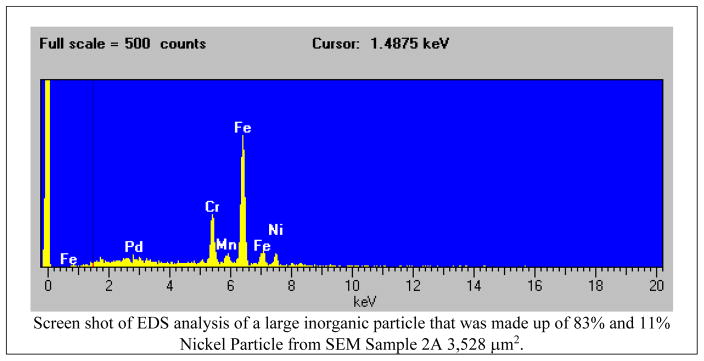

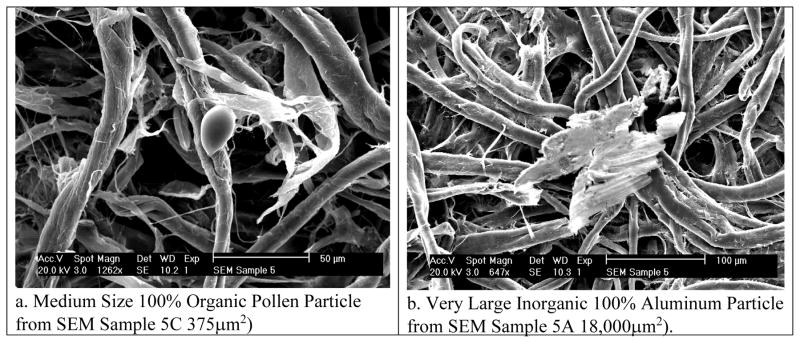

The 2000 model of FEI XL-30 Field Emission ESEM/SEM, which has an interface with Windows NT software (FEI MCNT UI), was used for the analysis of the samples. This model has a magnification range of 100X to 100,000X. An onboard field emission gun tip provides a very narrow diameter electron beam, resulting in very high resolution imaging. This instrument is also equipped with an EDS/X-Ray spectrometer. For this study, the electron beam was focused on the entire palladium-coated field of each 5mm Schirmer strip. The entire sample field was then scanned manually and every detectable particle was analyzed to assess the particle load, size, morphology, and type (i.e. chemical composition). First, the total number of particles was counted manually by systematically browsing the entire sample. Next, each particle size was measured using the built-in tool in the software (Windows NT FEI MCNT UI) that allows drawing multiple axes on each identified particle (Figure 2) and elemental composition of each particle was determined using EDS (Figure 3). While spherical/elliptical particles were easy to measure with major and minor axes, multiple axes were overlaid on irregular shaped particles to compute the average size of the particles. Moreover, some particle morphologies were difficult to assess due to particle degradation and fragmentation of particles, especially organic particles, e.g. pollens (Figure 4a). EDS was used to assess the amount of non-organic elemental composition of each particle. The EDS technique detects x-rays emitted from the sample during bombardment by the electron beam to characterize the elemental composition of the analyzed volume.21 All particles that were EDS positive were labeled as non-organic (Figure 4b), and the rest except pollens were labeled as organic. Like all the samples, the unexposed blank sample was also analyzed in order to establish background image of the sample (Figure 1a).

Figure 2.

Particle size and chemical speciation of particles.

Figure 3.

Chemical composition of particles found on the Schirmer strips.

Figure 4.

Organic and inorganic particles on Schirmer strips determined using EDS.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table S2 in the supplementary online material (SOM), and the ocular surface exam findings and the corresponding particle characteristics in Table 1. As expected, no particles were detected on the field blank. However, all six exposed samples showed particle loading, ranging from 1 to 33 particles. Mostly coarse particles were observed with an average particle size of 19.7 μm (standard deviation 4.7 μm; range 3.7 μm to 140 μm). All samples had organic particles, and five of the six samples also showed non-organic particles (Table 1). Most organic particles were unidentifiable due to degradation, although some were found to be pollen particles. The non-organic particles were composed of silicon, minerals, and metals including gold and titanium. The size of aluminum (4b) and iron particles was ≥ 62 μm, whereas the size zinc and gold < 20 μm (Table 2). Most metal particles were elongated, as compared to the organic particles including pollen that were round (Figure 4a).

Table 1.

Particle concentration, type, size and shape and select OSD signs.

| ID | # PM (NOr; Or) | PM size ± 95% CI (μm) | # of particles by shape | Smoking | DEQ5 (0–22) | TBUT† (second) | Staining† (0–15) | Schirmer† (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round | 3-D* | other | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 (0; 1) | 15.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Former | 20 | 9.6 | 0 | 26 |

| 2 | 5 (2; 3) | 49.1 ± 45.50 | 1 | 1 | 3 | Current | 6 | 12.3 | 1 | 13 |

| 3 | 5 (3; 2) | 37.3 ± 21.41 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Never | 15 | 11.3 | 4 | 14 |

| 4 | 9 (1; 8) | 27.7 ± 10.36 | 2 | 1 | 6 | Never | 4 | 2.6 | 5 | 20 |

| 5 | 17 (6; 11) | 16.5 ± 5.73 | 4 | 1 | 12 | Current | 9 | 20.3 | 0 | 31 |

| 6 | 33 (16; 4) | 12.3 ± 2.80 | 6 | 2 | 25 | Former | 9 | 7.3 | 3 | 31 |

NOr=non-organic; Or=organic; DEQ5=dry eye questionnaire 5; TBUT=tear break up time (second);

particle that appeared three dimensional (e.g. cube, spherical, diamond);

left eye

Table 2.

Number of particles by dominant element. (i.e. the element that showed the highest % in EDS).

| Type | 4 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 5 | # of particles | Particle size (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 90.0 ± 98.0 |

| Calcium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 9.9 ± 3.3 |

| Chlorine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.7 |

| Copper | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8.9 ± 3.3 |

| Glass | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7.3 ± 2.8 |

| Gold | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 18.5 |

| Iron | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 62.0 |

| Salt | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Silicon | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 13.0 ± 6.54 |

| Sodium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 18.6 |

| Sulfur | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 12.0 |

| Titanium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.0 |

| Zinc | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 14.2 ± 4.7 |

| Organic | 8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 25 | 25.4 ± 6.5 |

| Pollen | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 16.8 ± 4.6 |

| NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 12.2 ± 4.6 |

| Total | 9 | 5 | 1 | 33 | 5 | 17 | 70 | 19.8 ± 4.7 |

Although the sample size was relatively small to draw any meaningful statistical inferences, different signs of ocular surface disease were compared with respect to particle characteristics. With the exception of one sample (subject #1) tear production (measured by the length of wetting of Schirmer strips) was higher for samples with 9 or more particles (mean = 17.6 mm, SD=7.2 mm; mean =27.3,SD=6.3; p~.079); and the average particle size on these samples was ≤ 27.7μm, suggesting greater tearing with the elevated concentration of PM loading. Two samples with the highest particle loading (i.e. ≥ 17) also had the highest tearing level (31 mm) (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The application of SEM/EDS is becoming increasingly important in biomedical research.22 A review of these applications is summarized in the supplementary online material (SOM). This paper demonstrated successful application of SEM/EDS to successfully ascertain concentration, size, chemical composition and morphology of PM on Schirmer strips, which has important implications for advancing the research on the effects of PM on ocular surface disease (OSD). There is overwhelming evidence that PM exposure leads to oxidative stress with a downstream cascade of biological responses that have been implicated in both circulatory and pulmonary disease.23 For example, PM2.5 exposure has been found to contribute to the development of atherosclerosis24, facilitate vasomotor dysfunction and plaque progression25, thicken alveolar walls, and increase both serum and lung homogenate26 due to its pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory properties. The assessment of PM on the ocular surface will enable researchers to assess biological manifestations of PM exposure on the ocular surface.

There is biologic plausibility that particles found on the Schirmer strips can affect ocular surface health. For example, PM exposure can cause both oxidative stress and physical abrasions, with subsequent pro-inflammatory effects.4 Non-organic coarse particles, in particular, have greater potential to abrade the ocular surface, and this effect can be potentiated by eye rubbing.4 Organic particles, such as pollens, contain allergenic proteins that can also induce a pro-inflammatory response.27

While the results of the present research are encouraging, these results must be interpreted in the light of the limitations of this study, which include a small sample size, a specific population, and technical concerns (e.g. assessing the Schirmer bulb only as opposed to the entire strip). Since some particles can be deposited on other parts of the strip, the analysis of Schirmer bulb alone might have underestimated the particle loading on the strips. Furthermore, some of the particles were fragmented which made it difficult to assess particle count, size, and morphology. However, a detailed comparison could be made between fragmented particles and intact particles to ensure correct classification of exposure. Despite these limitations, we demonstrated the feasibility of PM characterization on Schirmer strips, which has potential implications to enhance the study of the role of the microenvironment in OSD. Future studies will be needed to analyze the entire Schirmer strip and automate SEM/EDS,28 because in this study, all samples were analyzed manually which was a time and labor intensive process (~3 hours per sample). While this was the first attempt to demonstrate the applicability of SEM/EDS as a useful modality to assess PM exposure on the ocular surface, future studies should be geared towards assessing the role of the loading, size and chemical speciation of PM in the ocular surface diseases and disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: Supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Clinical Sciences Research [EPID-006-15S], National Institute of Health [EY026174; Center Core Grant P30EY014801] and Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Grant.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no commercial or proprietary interest in any concept or product described in this article.

References

- 1.Krausko J, Runstuk J, Nedela V, et al. Observation of a brine layer on an ice surface with an environmental scanning electron microscope at higher pressures and temperatures. Langmuir. 2014 May 20;30:5441–5447. doi: 10.1021/la500334e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGregor JE, Donald AM. ESEM imaging of dynamic biological processes: the closure of stomatal pores. J Microsc. 2010 Aug 1;239:135–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2009.03351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters TM, Elzey S, Johnson R, et al. Airborne monitoring to distinguish engineered nanomaterials from incidental particles for environmental health and safety. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2009 Feb;6:73–81. doi: 10.1080/15459620802590058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolkoff P. Ocular discomfort by environmental and personal risk factors altering the precorneal tear film. Toxicology Letters. 2010 Dec 15;199:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borm PJ, Kelly F, Kunzli N, et al. Oxidant generation by particulate matter: from biologically effective dose to a promising, novel metric. Occup Environ Med. 2007 Feb;64:73–74. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.029090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newby DE, Mannucci PM, Tell GS, et al. Expert position paper on air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2015 Jan 7;36:83–93b. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donaldson K, Mills N, MacNee W, et al. Role of inflammation in cardiopulmonary health effects of PM. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005 Sep 1;207:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambroz A, Vlkova V, Rossner P, Jr, et al. Impact of air pollution on oxidative DNA damage and lipid peroxidation in mothers and their newborns. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2016 Aug;219:545–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pope CA, 3rd, Dockery DW. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. J Air Waste Manage. 2006 Jun;56:709–742. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. [Accessed 04/05/2011];Meta-analysis of time-series studies and panel studies of particulate matter and ozone. 2004 http://www.euro.who.int/document/e82792.pdf. 2011.

- 11.Burnett RT, Pope CA, 3rd, Ezzati M, et al. An integrated risk function for estimating the global burden of disease attributable to ambient fine particulate matter exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2014 Apr;122:397–403. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stafoggia M, Cesaroni G, Peters A, et al. Long-Term Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Incidence of Cerebrovascular Events: Results from 11 European Cohorts within the ESCAPE Project. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2014 Sep;122:919–925. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gleason JA, Bielory L, Fagliano JA. Associations between ozone, PM2.5, and four pollen types on emergency department pediatric asthma events during the warm season in New Jersey: a case-crossover study. Environ Res. 2014 Jul;132:421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao J, Wollmer P. Air pollutants and tear film stability--a method for experimental evaluation. Clin Physiol. 2001 May;21:282–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.2001.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galor A, Kumar N, Feuer W, et al. Environmental factors affect the risk of dry eye syndrome in a United States veteran population. Ophthalmology. 2014 Apr;121:972–973. e971. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rios JL, Boechat JL, Gioda A, et al. Symptoms prevalence among office workers of a sealed versus a non-sealed building: associations to indoor air quality. Environ Int. 2009 Nov;35:1136–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heal MR, Kumar P, Harrison RM. Particles, air quality, policy and health. Chem Soc Rev. 2012 Oct 7;41:6606–6630. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35076a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JA, Albeitz J, Begley C, et al. The epidemiology of dry eye disease: Report of the Epidemiology Subcommittee of the international Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) Ocular Surface. 2007 Apr;5:93–107. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Höflinger G. [Accessed May 18th, 2016]; [Accessed 05/08/2014, 2014];Brief Introduction to Coating Technology for Electron Microscopy. 2013 http://www.leica-microsystems.com/science-lab/brief-introduction-to-coating-technology-for-electron-microscopy/August 28th, 2013.

- 20.J. K. SC7620 ‘Mini’ Sputter Coater/Glow Discharge System Specification. Quorum Technologies; 2016. [Accessed 07/06/2016]. http://83.169.23.21/files/downloads/quorum/en/SC7620_Specification_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.MEE. Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy. 2016 http://mee-inc.com/eds.html.

- 22.Muscariello L, Rosso F, Marino G, et al. A critical overview of ESEM applications in the biological field. J Cell Physiol. 2005 Dec;205:328–334. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pei Y, Jiang R, Zou Y, et al. Effects of Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5) on Systemic Oxidative Stress and Cardiac Function in ApoE(−/−) Mice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13 doi: 10.3390/ijerph13050484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai Y, Sun Q. Fine particulate matter air pollution and atherosclerosis: Mechanistic insights. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 May 6; doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moller P, Christophersen DV, Jacobsen NR, et al. Atherosclerosis and vasomotor dysfunction in arteries of animals after exposure to combustion-derived particulate matter or nanomaterials. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2016 May;46:437–476. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2016.1149451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang R, Dai Y, Zhang X, et al. Reduced pulmonary function and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines in nanoscale carbon black-exposed workers. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2014;11:73. doi: 10.1186/s12989-014-0073-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelikan Z. Mediator profiles in tears during the conjunctival response induced by allergic reaction in the nasal mucosa. Mol Vis. 2013;19:1453–1470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters TM, Sawvel EJ, Willis R, et al. Performance of Passive Samplers Analyzed by Computer-Controlled Scanning Electron Microscopy to Measure PM10-2.5. Environ Sci Technol. 2016 Jul 19;50:7581–7589. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b01105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.