Abstract

Plasma levels of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 (IGFBP-2) have been associated with Alzheimer's disease (AD) and brain atrophy. Some evidence suggests a potential synergistic effect of IGFBP-2 and AD neuropathology on neurodegeneration, while other evidence suggests the effect of IGFBP-2 on neurodegeneration is independent of AD neuropathology. Therefore, the current study investigated the interaction between plasma IGFBP-2 and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of AD neuropathology on hippocampal volume and cognitive function. AD Neuroimaging Initiative data were accessed (n=354, 75±7 years, 38% female), including plasma IGFBP-2, CSF total tau, CSF Aβ-42, MRI-quantified hippocampal volume, and neuropsychological performances. Mixed effects regression models evaluated the interaction between IGFBP-2 and AD biomarkers on hippocampal volume and neuropsychological performance, adjusting for age, sex, education, APOE ε4 status, and cognitive diagnosis. A baseline interaction between IGFBP-2 and CSF Aβ-42 was observed in relation to left (t(305)=-6.37, p=0.002) and right hippocampal volume (t(305)=-7.74, p=0.001). In both cases, higher IGFBP-2 levels were associated with smaller hippocampal volumes but only among amyloid negative individuals. The observed interaction suggests IGFBP-2 drives neurodegeneration through a separate pathway independent of AD neuropathology.

Keywords: Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2, Insulin-like growth factor-I, Insulin-like growth factor-II, Alzheimer's disease, Hippocampus, Memory

1. Introduction

The most common neuropathological presentation of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a mixed pathology which includes plaques, tangles, and cerebrovascular disease (Schneider, Arvanitakis, et al., 2007; Schneider & Bennett, 2010; Troncoso et al., 2008). Thus, it is not surprising that vascular risk factors have been associated with incident AD (Kivipelto et al., 2002) and type-2 diabetes in particular has been associated with a two-fold higher risk of incident AD (Sims-Robinson et al. 2010). There is some evidence that diabetes may have a direct effect on the AD neuropathological cascade. Multiple interacting pathways between insulin signaling and AD neuropathology have been identified, including insulin-related alterations in glycogen synthase kinase 3 (a known tau kinase) and insulin-related alterations in amyloid clearance via insulin degrading enzyme (for review see Stanley, Macauley, & Holtzman, 2016). Moreover, insulin and its receptors are highly expressed in brain regions relevant to AD pathogenesis, including the medial temporal lobe, and play an important role in episodic memory functioning (McNay & Recknagel, 2011), suggesting that insulin abnormalities may be particularly damaging in the presence of co-occurring AD neuropathology. Yet, other findings suggest diabetes and insulin abnormalities drive neurodegeneration through an independent pathway. Autopsy findings, for example, indicate that the increased risk of clinical AD associated with type-2 diabetes is driven by cerebrovascular pathology rather than amyloid plaques or tau tangles (Abner et al., 2016; Ahtiluoto et al., 2010, Arvanitakis et al., 2006).

One pathway implicated in the interaction between insulin and AD neuropathology is the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling pathway (Laviola et al., 2007). This pathway includes IGFs, IGF receptors, and IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs). IGFs promote hippocampal survival in the presence of neurotoxins (Dore et al., 1997), including the amyloid-β peptide (Wei et al., 2002). However, IGFBPs restrict the availability of IGFs, reducing their neuroprotective effects (Mackay et al., 2003). Peripheral levels of both IGF-1 (Westwood et al., 2014) and IGFBP-2 (Doecke et al., 2012) have been associated with an increased risk of clinical AD. Additionally, there is growing evidence that of the six high-affinity IGF-binding proteins, IGFBP-2 may have a specific role in AD pathophysiology. Individuals with AD have elevated levels of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma IGFBP-2 compared to cognitively normal older adults (Doecke et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2012; O'Bryant et al., 2010; Toledo et al., 2013), and plasma levels of IGFBP-2 are associated with a pronounced AD-like pattern of brain atrophy (Toledo et al., 2013). In the context of such neurodegeneration, Toledo et al. 2013 noted that plasma IGFBP-2 levels correlate with CSF total tau levels; thus IGFBP-2 may drive neurodegeneration by exacerbating IGF-1 signaling defects among individuals with AD neuropathology. However, a second alternative hypothesis is that the role of IGFBP-2 does not depend on the presence of AD neuropathology per se, but rather promotes neurodegeneration through a non-AD neurotrophic signaling pathway.

The current study will therefore assess the potential synergistic effect of plasma IGFBP-2 levels and CSF biomarkers of AD neuropathology. First, we extend previous work (e.g., Toledo et al., 2013) by assessing the association between IGFBP-2 and AD-relevant outcomes, including hippocampal volume, episodic memory function, and executive function. Second, we assess the interaction between CSF biomarkers of AD neuropathology and IGFBP-2 on these same AD-relevant outcomes. We hypothesize that, similar to effect of vascular risk factors (Hohman et al., 2015), IGFBP-2 acts through a non-AD pathway and thus will show the strongest association with hippocampal volume, episodic memory performance, and executive function performance among biomarker negative individuals.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1 Participants

Participant data were drawn from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI; http://adni.loni.ucla.edu/) launched in 2004 to examine neuroimaging biomarkers in the progression of MCI and AD. The original ADNI study enrolled approximately 800 participants, aged 55-90 years, excluding history of serious neurological disease other than AD (e.g., Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis), brain lesion (e.g., infarction), head trauma, or psychoactive medication use. For full inclusion/exclusion criteria see http://www.adni-info.org. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants at each site, and analysis of ADNI's publicly available database was approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board prior to data analysis.

Data for the present study were accessed on 06/01/2015 and limited to ADNI 1 cohort participants with available structural 1.5T neuroimaging, plasma IGFBP-2 and CSF IGFBP-2, CSF AD biomarker, and neuropsychological data. After excluding participants who did not pass the quality control procedures (defined in detail below), these restrictions resulted in a baseline sample size of 354 participants for the current study.

2.2 Cognitive Diagnostic Classification

Normal cognition was defined as a) a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975) score between 24 and 30, b) a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR; Morris, 1993) global score of 0 (no dementia), c) preserved activities of daily living, and d) not meeting MCI or dementia criteria as described below. MCI was based upon the Petersen criteria (Petersen, 2004; Winblad et al., 2004) and defined as a) MMSE score between 24 and 30, b) a memory complaint by participant, informant, or clinician, c) objective memory impairment as measured by education-adjusted scores on the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Logical Memory II, d) a CDR≤0.5, e) relatively spared activities of daily living, and f) not meeting criteria for AD. AD was defined as a) MMSE score between 20 and 26, b) CDR of 0.5 or 1.0, c) objective cognitive impairment (i.e., performances falling 1.5 standard deviations below the age-adjusted normative mean) in at least two cognitive domains (i.e., memory, language, attention or executive functioning), (d) impairment in activities of daily living directly attributable to cognitive decline; and e) meeting NINCDS/ADRDA criteria for probable AD (McKhann et al., 1984).

2.3 Plasma IGFBP-2

Overnight fasting plasma samples were drawn during the baseline study visit and analyzed as part of the Biomarkers Consortium Plasma Proteomics Project Rules Based Medicine (RBM) multiplex data with the Luminex xMAP platform by Myriad Rules-Based Medicine, which uses a flow-based laser apparatus and fluorescent polystyrene microspheres to detect biomarker concentrations. The number of analytes in each panel is limited by dynamic range, matrix interference, and cross-reactivity, and the actual combination of analytes in a panel is proprietary to RBM. Each plate is run in triplicate to ensure high quality results. Plasma IGFBP-2 levels were measured as part of analyte panels following strict quality control procedures that included exclusion of analytes with more than 10% missing or more than 10% recorded below the detectable assay limit, imputation of variables with less than 10% missing, removal of outliers, and transformation to normal distributions. The IGFBP-2 assay has a least detectable dose of 1.2ng/mL and a lower assay limit of 0.27ng/mL. The least detectable dose is considered the lowest reliable level for the assay, and anything lower is associated with greater error. All IGFBP-2 levels were greater than the least detectable dose (1.48-2.56ng/mL). IGF-1 was measured by ADNI but failed to pass quality control procedures and therefore was not used in these analyses. IGF-2 was not measured by ADNI, so was unavailable for analysis. Further details regarding the plasma analysis can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/BC_Plasma_Proteomics_Data_Primer.pdf and http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/BC-Plasma-Proteomics-Analysis-Plan.pdf.

2.4 CSF Protocol

Overnight fasting CSF samples were drawn during the baseline study visit according to the standard ADNI protocol. Full procedural details can be found at: http://www.adni-info.org/Scientists/ADNIStudyProcedures.html.

Aβ-42 and total tau were measured using the xMAP Luminex platform and Innogentics/Fujirebio AlzBio3 immunoassay kits following study protocol at University of Pennsylvania that utilizes standard manufacturer procedures (Kang et al., 2012; Olsson et al., 2005; Shaw et al., 2011, 2009). Quality control procedures included retesting of a subset of the samples to ensure reproducibility of results. Aβ-42 and tau were treated as continuous variables in all statistical models. For illustration, biomarker positivity was defined based on previously established cut-points of Aβ-42 ≤ 192 (amyloid positive) and total tau ≥ 93 (tau positive, Jagust et al., 2009).

For our secondary analyses, CSF IGFBP-2 was analyzed for a subsample of 298 individuals as part of the Biomarkers Consortium Project with the Luminex immunoassay developed by Myriad RBM (http://www.rbm.myriad.com). Analysis and quality control procedures were the same as those procedures used for plasma analysis. Further details regarding the CSF analysis can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/2011Dec28-Biomarkers-Consortium-Data-Primer-FINAL1.pdf.

2.5 Neuroimaging Quantification of Hippocampal Volume

Brain MRI was captured at baseline and at each subsequent visit on a 1.5T MRI using a T1-weighted sagittal volumetric magnetization rapid gradient echo sequence (1.25mm × 1.25mm × 1.20mm) following the ADNI protocol (Jack et al., 2008) standardized across ADNI sites (Wyman et al., 2013). FreeSurfer Version 4.4 was utilized for cortical reconstruction and volumetric segmentation of the hippocampus and intracranial volume (http://freesurfer.net/; Dale et al., 1999; Desikan et al., 2006; Fischl et al., 1999a, 1999b; Reuter et al., 2012). Hemispheric hippocampal volumes were examined independently to account for any asymmetrical differences (Shi et al., 2009).

2.6 Neuropsychological Assessment

A neuropsychological protocol was administered at baseline and each subsequent visit capturing multiple cognitive domains (for details, see http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/ADNI_GeneralProceduresManual.pdf). Domain composite scores were used for episodic memory (Crane et al., 2012) and an inclusive model of executive function (Gibbons et al., 2012). These composites were previously derived using confirmatory factor analysis at baseline and subsequent longitudinal evaluations and are available for download from the ADNI website. The episodic memory composite is comprised of scores from the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, AD Assessment Scale Cognitive Subscale, 3 word recall portion of the MMSE, and Logical Memory I and II. The executive composite is comprised of scores from Trail Making Test Parts A and B, Digit Span Backward, Digit Symbol, Animal Fluency, Vegetable Fluency, and Clock Drawing Test. The executive function measure was designed to be inclusive of all ADNI tests measuring some aspect of executive function, rather than only frontal lobe function, to capture any AD-associated impairment (Gibbons et al., 2012). For the current study, composite scores were chosen over item-level analysis to reduce the number of comparisons.

2.7 Statistical Analyses

R Version 3.0.1 (http://www.r-project.org/) was used for all analyses. First we evaluated baseline demographic characteristics in relation to plasma IGFBP-2 using a single linear regression model with age, sex, education, diagnosis, Aβ-42, tau, and APOE ε4 status set as predictors, and plasma IGFBP-2 levels set as the outcome. Additional analyses evaluated demographic differences across diagnostic categories (Table 1). Significance for descriptive comparisons was set a priori as α=0.05.

Table 1.

Participant Baseline Characteristics

| Total n=354 |

NC n=58 |

MCI n=197 |

AD n=99 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 75±7 | 75±6 | 75±7 | 75±8 | 0.87 |

| Sex, % female | 38 | 49 | 33 | 43 | 0.04* |

| Education, years | 16±3 | 16±3 | 16±3 | 15±3 | 0.19 |

| APOE, % e4 positive | 50 | 9 | 52 | 69 | <0.001* |

| Plasma IGFBP-2, ng/mL | 101±57 | 85±43 | 115±69 | 84±23 | <0.001* |

| CSF IGFBP-2, ng/mL | 104±19 | 101±16 | 105±19 | 103±19 | 0.34 |

| Tau, pg/mL | 101±54 | 65±22 | 101±53 | 122±58 | <0.001* |

| Tau Positive, % | 46 | 17 | 45 | 64 | <0.001* |

| Aβ-42, pg/mL | 170±59 | 249±25 | 162±54 | 143±59 | <0.001* |

| Aβ-42 Positive, % | 68 | 2 | 75 | 91 | <0.001* |

| Left Hippocampal Volume, mm3 | 3121±595 | 3641±427 | 3125±546 | 2856±589 | <0.001* |

| Right Hippocampal Volume, mm3 | 3160±610 | 3686±473 | 3170±573 | 2879±618 | <0.001* |

| Episodic Memory Composite | −0.16±0.77 | 0.87±0.46 | −0.13±0.57 | −0.16±0.77 | <0.001* |

| Executive Function Composite | −0.18±0.91 | 0.70±0.57 | −0.06±0.74 | −0.18±0.91 | <0.001* |

Note: Data presented as mean and standard deviation or frequency

p<0.05

For hypothesis testing, mixed effects regression tested the baseline and longitudinal associations between plasma IGFBP-2 and left hippocampal volume, right hippocampal volume, episodic memory performance, and executive function performance. A Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons (0.05/24 comparisons resulting in a family-wise error rate of α=0.002). To test the association between plasma IGFBP-2 and baseline outcomes, the mixed model fixed effects included the intercept, baseline age, education, sex, baseline diagnosis, APOE ε4 status, time interval and intracranial volume (as appropriate for brain MRI analyses). Random effects included intercept and time interval. To test the association between plasma IGFBP-2 and AD relevant outcomes over time, models included the interaction between plasma IGFBP-2 and time interval as an additional fixed effect model term.

Next, mixed effects regression models tested the interaction between plasma IGFBP-2 and CSF AD biomarkers (Aβ-42 and tau) on baseline and longitudinal left hippocampal volume, right hippocampal volume, episodic memory performance, and executive function performance. Baseline models included the same fixed and random effects reported above with an additional plasma IGFBP-2 × CSF biomarker interaction term. Longitudinal models included a three-way plasma IGFBP-2 × CSF biomarker × time interval interaction and also included the relevant lower-order two-way interaction terms.

Supplemental analyses were performed in which plasma IGFBP-2 levels were replaced with CSF levels of IGFBP-2 to assess potential differences across biological fluids.

3. Results

3.1 Participant Characteristics

Age (F(1,344)=40367, p<0.001 was associated with plasma IGFBP-2 levels. Sex, education, Aβ-42, tau, and APOE ε4 status were not associated with plasma IGFBP-2 levels (all p-values>0.05). We also observed an association between baseline diagnosis and plasma IGFBP-2 (F(2, 347)=12.34, p<0.001) whereby MCI individuals had the highest plasma IGFBP-2 levels compared to individuals with NC or AD.

3.2 Main Effect of Plasma IGFBP-2

After correction for multiple comparisons, plasma IGFBP-2 was unrelated to all baseline and longitudinal outcomes. We did observe nominal associations between plasma IGFBP-2 and baseline right hippocampal volume (t(345)=-2.31, p=0.02; see Table 2) and baseline episodic memory performance (t(346)=-2.06, p=0.04; see Table 2), such that higher plasma IGFBP-2 was associated with smaller hippocampal volumes and worse episodic memory performance.

Table 2.

Plasma IGFBP-2 × CSF Biomarker Outcomes

| Variable | IGFBP-2 | IGFBP-2 × Aβ-42 | IGFBP-2 × Tau | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | ΔR2 | p Value | β | ΔR2 | p Value | β | ΔR2 | p Value | |

| Cross-Sectional Outcomes | |||||||||

| Left Hippocampal Volume | −218.219 | 0.008 | 0.09 | −6.365 | 0.022 | <0.002* | 0.118 | 0.001 | 0.96 |

| Right Hippocampal Volume | −307.081 | 0.011 | 0.02 | −7.711 | 0.027 | <0.001* | 2.367 | 0.001 | 0.32 |

| Episodic Memory Composite | −0.327 | 0.011 | 0.04 | −0.004 | 0.002 | 0.15 | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.39 |

| Executive Function Composite | −0.247 | 0.005 | 0.24 | 8.7×104 | 0.000 | 0.79 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.79 |

| Longitudinal Outcomes | |||||||||

| Left Hippocampal Volume | −0.038 | 0.001 | 0.42 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.13 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.09 |

| Right Hippocampal Volume | −0.025 | 0.001 | 0.61 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.30 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.30 |

| Episodic Memory Composite | −1.8×104 | 0.007 | 0.17 | −3.636 | 0.000 | 0.85 | 4.205 | 0.004 | 0.08 |

| Executive Function Composite | −1.4×104 | 0.002 | 0.41 | −4.314 | 0.002 | 0.07 | 5.934 | 0.003 | 0.05 |

Note: Data presented as mean and standard deviation or frequency. ΔR2 represents difference in marginal R2 for mixed effects regression model excluding the term of interest compared to mixed effects regression model including term of interest.

highlights significant effects that survive Bonferroni correction.

3.3 Interaction between Plasma IGFBP-2 and AD Biomarkers

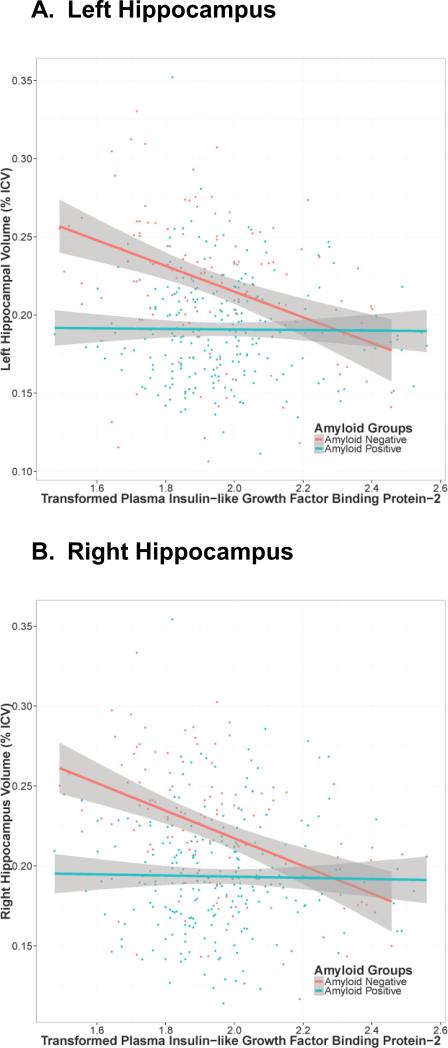

In biomarker interaction analyses, plasma IGFBP-2 interacted with Aβ-42 levels on both left (t(343)=-3.14, p=0.002) and right hippocampal volume (t(343)=-3.70, p=0.0002, see Table 2). Both interactions remained statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons. In both cases, plasma IGFBP-2 was associated with smaller hippocampal volumes but only in those individuals with higher Aβ-42 levels (i.e., less biomarker evidence of AD pathology; see Figure 1). We also observed a nominal interaction between plasma IGFBP-2 and tau on executive function performance (t(1689)=2.08, p=0.04) that did not survive correction for multiple comparisons. There were no additional interactions between plasma IGFBP-2 levels and Aβ-42 or tau on brain or cognitive outcomes.

Figure 1. Hippocampal Volume and Plasma IGFBP-2 by Aβ-42 Biomarker Status.

Transformed plasma Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 (IGFBP-2; box-cox transformation) levels are on the x-axis, left (panel A) and right (panel B) hippocampus volume is on the y-axis. Points and lines are colored based on amyloid positivity as previously defined in ADNI where CSF Aβ-42 ≤192 is classified as “Amyloid Positive” and CSF Aβ-42 > 192 is classified as “Amyloid Negative”. Grey shading represents the 95% confidence intervals. There is a negative association between increasing levels of IGFBP-2 and hippocampal volume among amyloid negative individuals. Amyloid groupings are for illustration purposes only.

In supplemental analyses, CSF IGFBP-2 levels were correlated with plasma levels of IGFBP-2 (R=0.15, p=0.04). We observed associations consistent with our plasma IGFBP-2 analyses when using CSF IGFBP-2, although no effects survived correction for multiple comparisons (see Supplemental Table 1).

4. Discussion

The current study investigated the interaction between IGFBP-2 and CSF AD biomarkers on hippocampal volume, episodic memory performance, and executive function performance. We observed an interaction between plasma IGFBP-2 and CSF Aβ-42 on left and right hippocampal volume at baseline whereby high IGFBP-2 levels were associated with smaller hippocampal volumes among amyloid negative individuals. Our results suggest that the neurodegenerative effects of IGFBP-2 may act through an independent, non-amyloid pathway.

The present results have important clinical implications, as findings highlight the effect of IGFBP signaling among amyloid negative individuals. In previous work leveraging both ADNI data and autopsy data from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC), we observed a comparable interaction between the Framingham Stroke Risk Profile and CSF biomarkers of AD neuropathology whereby the effect of vascular risk on hippocampal volume and cognition was strongest among individuals who were AD biomarker negative (Hohman et al., 2015). The results of both the current and previous work support the possibility that vascular and insulin interventions for cognitive impairment may be most beneficial among individuals who are AD biomarker negative.

The mechanism underlying the observed IGFBP-2 effect remains somewhat unclear. Among the 6 known IGF binding proteins, IGFBP-2 is the most abundant in the brain (Hertze et al., 2014) and has an active role in neural development and neuroprotection through IGF signaling. The lack of an association between IGFBP-2 and hippocampal volume among amyloid positive individuals suggests that any neuroprotective effects of IGFBP-2 may be overwhelmed by the neurodegenerative effects of AD neuropathology. Unfortunately, the present project was unable to evaluate IGF-1 or IGF-2 signaling that likely partially or fully mediates the effects of IGFBP-2 on neurodegeneration and cognitive decline. There is evidence that the neurotrophic effects of IGFs protect neurons against amyloid toxicity (Dore et al.,1997), so without direct measurement of IGF it remains possible that interactions between IGFs and amyloid result in an altered or reduced effect of IGFBP-2 in the presence of high levels of amyloid. Co-measurement of peripheral and central levels of IGFs and IGFBPs will be necessary to further elucidate the mechanisms of the interactions observed in the current study.

In contrast to previous reports (Hertze et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2012; Tham et al., 1993), we observed higher plasma IGFBP-2 levels in individuals with MCI compared to those with NC and AD. Previous analyses did not assess MCI or collapsed MCI and AD into a single group, so it is unknown whether the diagnostic group differences seen here were similarly present in these previous cohorts. A second possibility is that, due to eligibility restrictions limiting overt cerebrovascular disease in the ADNI cohort, the sample of AD patients here underrepresents the prevalence of co-occurring cerebrovascular disease that likely underlies previously observed IGFBP-2 effects. Such a selection bias may also reduce our ability to detect IGFBP-2 effects within amyloid positive participants, leaving open the possibility of a synergistic effect between IGFBP-2 and AD biomarkers on neurodegeneration within more representative cohorts.

The current study has a number of strengths. First, by utilizing the ADNI cohort, we had access to a number of factors that could be related to IGFBP-2, including a well characterized cohort of participants, plasma and CSF markers of IGFBP-2 and CSF biomarkers of AD, neuroimaging variables, and cognitive assessments. Few other cohorts would allow for such an in-depth assessment of a single factor in human models. Additionally, we were able to expand upon prior work (Royall et al., 2015; Toledo et al., 2013) and demonstrate an important interaction between IGFBP-2 and AD biomarkers. Despite these strengths, there are a few weaknesses related to the current study. First, the generalizability of the ADNI cohort is limited given the predominantly Caucasian and well-educated participant sample. Second, ADNI's methodological design was intended to support therapeutic discovery and the absence of repeat CSF or plasma IGFBP-2 levels precluded examination of longitudinal changes in IGFBP-2. It is important for future work to investigate such longitudinal associations to characterize relations between IGFBP-2 and brain aging.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that IGFBP-2 levels are related to neurodegeneration, particularly among amyloid negative individuals. IGFBP-2 may therefore be an important factor in predicting neurodegeneration through one or more non-AD pathological pathways.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

IGFBP-2 and AD biomarkers interact on hippocampal volume

Higher IGFBP-2 relate to smaller hippocampi among amyloid negative individuals

The effects of IGFBP-2 may drive neurodegeneration through independent, non-AD pathways

Acknowledgements

F32-AG046093 (EML), R01-AG034962 (ALJ), R01-HL111516 (ALJ), K24-AG046373 (ALJ), K12-HG043483 (TJH), Vanderbilt Memory & Alzheimer's Center; Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and generous contributions from: Alzheimer's Association; Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen Idec Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Medpace, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Synarc Inc.; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and study is coordinated by Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study at University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abner EL, Nelson PT, Kryscio RJ, Schmitt FA, Fardo DW, Woltjer RL, et al. Diabetes is associated with cerebrovascular but not Alzheimer's disease neuropathology. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2016;12(8):882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.006. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahtiluoto S, Polvikoski T, Peltonen M, Solomon A, Tuomilehto J, Winblad B, et al. Diabetes, Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia: a population-based neuropathologic study. Neurology. 2010;75(13):1195–202. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d7f8. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d7f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis Z, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Li Y, Arnold SE, Wang Z, Bennett DA. Diabetes is related to cerebral infarction but not to AD pathology in older persons. Neurology. 2006;67(11):1960–65. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247053.45483.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PK, Carle A, Gibbons LE, Insel P, Mackin RS, Gross A, Jones RN, Mukherjee S, Curtis SM, Harvey D, Weiner M, Mungas D. Development and assessment of a composite score for memory in the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Brain Imaging & Behavior. 2012;6:502–16. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9186-z. doi:10.1007/s11682-012-9186-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9:179–94. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. doi:10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Killiany RJ. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31:968–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doecke JD, Laws SM, Faux NG, Wilson W, Burnham SC, Lam C-P, Mondal A, Bedo J, Bush AI, Brown B, De Ruyck K, Ellis KA, Fowler C, Gupta VB, Head R, Macaulay SL, Pertile K, Rowe CC, Rembach A, Rodrigues M, Rumble R, Szoeke C, Taddei K, Taddei T, Trounson B, Ames D, Masters CL, Martins RN. Blood-based protein biomarkers for diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2012;69:1318–25. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.1282. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2012.1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore S, Kar S, Quirion R. Insulin-like growth factor I protects and rescues hippocampal neurons against -amyloid- and human amylin-induced toxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1997;94:4772–4777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4772. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.9.4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis. II: Inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage. 1999a;9:195–207. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0396. doi:10.1006/nimg.1998.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Sereno MI, Tootell RB, Dale AM. High-resolution intersubject averaging and a coordinate system for the cortical surface. Hum. Brain Mapp. 1999b;8:272–84. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)8:4<272::AID-HBM10>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons LE, Carle AC, Mackin RS, Harvey D, Mukherjee S, Insel P, Curtis SM, Mungas D, Crane PK. A composite score for executive functioning, validated in Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) participants with baseline mild cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging & Behavior. 2012;6:517–27. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9176-1. doi:10.1007/s11682-012-9176-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertze J, Nägga K, Minthon L, Hansson O. Changes in cerebrospinal fluid and blood plasma levels of IGF-II and its binding proteins in Alzheimer's disease: an observational study. BMC Neurology. 2014;14:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-64. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-14-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohman TJ, Samuels LR, Liu D, Gifford KA, Mukherjee S, Benson EM, et al. Stroke risk interacts with Alzheimer's disease biomarkers on brain aging outcomes. Neurobiology of Aging. 2015;36(9):2501–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.05.021. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WT, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM, Shaw LM, Perrin R, Arnold SE, Grossman M, Xiong C, Craig-Schapiro R, Clark CM, Pickering E, Kuhn M, Chen Y, Van Deerlin VM, McCluskey L, Elman L, Karlawish J, Chen-Plotkin A, Hurtig HI, Siderowf A, Swenson F, Lee VM-Y, Morris JC, Trojanowski JQ, Soares H. Plasma multianalyte profiling in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2012;79:897–905. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318266fa70. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318266fa70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Bernstein MA, Fox NC, Thompson P, Alexander G, Harvey D, Borowski B, Britson PJ, L Whitwell J, Ward C, Dale AM, Felmlee JP, Gunter JL, Hill DLG, Killiany R, Schuff N, Fox-Bosetti S, Lin C, Studholme C, DeCarli CS, Krueger G, Ward HA, Metzger GJ, Scott KT, Mallozzi R, Blezek D, Levy J, Debbins JP, Fleisher AS, Albert M, Green R, Bartzokis G, Glover G, Mugler J, Weiner MW. The Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): MRI methods. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2008;27:685–91. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21049. doi:10.1002/jmri.21049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagust WJ, Landau SM, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, et al. Relationships between biomarkers in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2009;73(15):1193–1199. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bc010c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J-H, Vanderstichele H, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM. Simultaneous analysis of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers using microsphere-based xMAP multiplex technology for early detection of Alzheimer's disease. Methods. 2012;56:484–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.03.023. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivipelto M, Laakso MP, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A, Soininen H. Hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia as risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: potential for pharmacological intervention. CNS Drugs. 2002;16(7):435–444. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216070-00001. doi:160701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviola L, Natalicchio A, Giorgino F. The IGF-I signaling pathway. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2007;13(7):663–9. doi: 10.2174/138161207780249146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay KB, Loddick SA, Naeve GS, Vana AM, Verge GM, Foster AC. Neuroprotective Effects of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-Binding Protein Ligand Inhibitors in Vitro and in Vivo. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2003;23(10):1160–1167. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000087091.01171.AE. doi:10.1097/01.WCB.0000087091.01171.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNay EC, Recknagel AK. Reprint of: “Brain insulin signaling: A key component of cognitive processes and a potential basis for cognitive impairment in type 2 diabetes.”. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2011;96(4):517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.11.001. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Bryant SE, Xiao G, Barber R, Reisch J, Doody R, Fairchild T, Adams P, Waring S, Diaz-Arrastia R. A serum protein-based algorithm for the detection of Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology. 2010;67:1077–81. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.215. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson A, Vanderstichele H, Andreasen N, De Meyer G, Wallin A, Holmberg B, Rosengren L, Vanmechelen E, Blennow K. Simultaneous measurement of beta-amyloid(1-42), total tau, and phosphorylated tau (Thr181) in cerebrospinal fluid by the xMAP technology. Clinical Chemistry. 2005;51:336–45. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.039347. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2004.039347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2004;256:183–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter M, Schmansky NJ, Rosas HD, Fischl B. Within-subject template estimation for unbiased longitudinal image analysis. Neuroimage. 2012;61:1402–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.084. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royall DR, Bishnoi RJ, Palmer RF. Serum IGF-BP2 Strongly Moderates Age's Effect on Cognition: A MIMIC Analysis. Neurobiology of Aging. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.04.003. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69(24):2197–2204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JA, Bennett D. Where Vascular Meets Neurodegenerative Disease. Stroke. 2010;41:S144–S146. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.598326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Clark CM, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon A, Lewczuk P, Dean R, Siemers E, Potter W, Lee VM-Y, Trojanowski JQ. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Annals of Neurology. 2009;65:403–13. doi: 10.1002/ana.21610. doi:10.1002/ana.21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Figurski M, Coart E, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon AJ, Lewczuk P, Dean RA, Siemers E, Potter W, Lee VM-Y, Trojanowski JQ. Qualification of the analytical and clinical performance of CSF biomarker analyses in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:597–609. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0808-0. doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0808-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi F, Liu B, Zhou Y, Yu C, Jiang T. Hippocampal volume and asymmetry in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: Meta-analyses of MRI studies. Hippocampus. 2009;19(11):1055–1064. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20573. doi:10.1002/hipo.20573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Robinson C, Kim B, Rosko A, Feldman EL. How does diabetes accelerate Alzheimer disease pathology? Nature Reviews Neurology. 2010;6(10):551–9. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.130. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2010.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley M, Macauley SL, Holtzman DM. Changes in insulin and insulin signaling in Alzheimer's disease: cause or consequence? The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2016;213(8):1375–1385. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160493. doi:10.1084/jem.20160493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham A, Nordberg A, Grissom FE, Carlsson-Skwirut C, Viitanen M, Sara VR. Insulin-like growth factors and insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in cerebrospinal fluid and serum of patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type. J. Neural Transm. Park. Dis. Dement. Sect. 1993;5:165–76. doi: 10.1007/BF02257671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo JB, Da X, Bhatt P, Wolk DA, Arnold SE, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Davatzikos C. Relationship between plasma analytes and SPARE-AD defined brain atrophy patterns in ADNI. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055531. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso JC, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM, Crain B, Pletnikova O, O'Brien RJ. Effect of infarcts on dementia in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Annals of Neurology. 2008;64(2):168–176. doi: 10.1002/ana.21413. doi:10.1002/ana.21413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Wang X, Kusiak JW. Signaling events in amyloid beta-peptide-induced neuronal death and insulin-like growth factor I protection. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(20):17649–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111704200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwood AJ, Beiser A, Decarli C, Harris TB, Chen TC, He X-M, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 and risk of Alzheimer dementia and brain atrophy. Neurology. 2014;82(18):1613–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000382. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund L-O, Nordberg A, Bäckman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon M, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack C, Jorm A, Ritchie K, van Duijn C, Visser P, Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2004;256:240–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman BT, Harvey DJ, Crawford K, Bernstein MA, Carmichael O, Cole PE, Crane PK, DeCarli C, Fox NC, Gunter JL, Hill D, Killiany RJ, Pachai C, Schwarz AJ, Schuff N, Senjem ML, Suhy J, Thompson PM, Weiner M, Jack CR. Standardization of analysis sets for reporting results from ADNI MRI data. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2013;9:332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.06.004. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.