Introduction

KEY TEACHING POINTS

|

The number of radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFA) procedures performed in the epicardial space is increasing.1 Major acute complications (primarily pericardial bleeding) and delayed complications have been reported in 5% and 2% of cases, respectively.2, 3, 4 To the best of our knowledge, a single case of constrictive pericarditis after multiple epicardial ablations for ventricular tachycardia has been reported.5 We describe a late presentation of constrictive pericarditis that occurred after a single percutaneous epicardial procedure with limited ablation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia.

Case report

A 52-year-old man with asthma developed palpitations and, after extensive evaluation, was diagnosed with inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Palpitations were refractory to diltiazem and flecainide therapy, and ivabradine was unavailable. He underwent an electrophysiology study and endocardial activation mapping. RFA of the sinus node region was incomplete owing to proximity to the phrenic nerve. His symptoms became disabling and therefore, he underwent an endocardial-epicardial ablation 3 months later.

Uncomplicated percutaneous subxyphoid epicardial access was obtained with a Tuohy needle as described by Sosa et al.6 An 8F sheath was advanced over the wire and a second long wire (Wholey) was advanced into the same sheath to implement a double wire technique. A peripheral angioplasty balloon was placed through a deflectable sheath (Agilis; St Jude Medical, Minneapolis, MN) to displace the phrenic nerve, and the RFA catheter was advanced to the right atrium (Figure 1). Radiofrequency energy using a Biosense-Webster Thermocool SF catheter (Diamond Bar, CA) was delivered in the endocardium. The ablation catheter and the angioplasty balloon were both removed and the ablation catheter was inserted into the epicardial space through the deflectable sheath, and 5 focal lesions were delivered in the epicardium overlying the sinus node. At the end of the procedure his heart rate decreased from 140 to 70 beats per minute. Kenalog (1 mg/kg) was injected into the pericardial space and the epicardial sheath was removed immediately after the procedure. The fluid was serous, without any evidence of bleeding, throughout the case. Twelve hours after the procedure, the patient developed pleuritic chest pain, treated with indomethacin, colchicine, and his home dose of aspirin 81 mg daily. New diffuse ST-segment elevations were noted on electrocardiogram, consistent with acute pericarditis (Figure 2). An echocardiogram showed no effusion. His chest pain resolved in 48 hours and he was discharged 3 days after the procedure. The indomethacin and colchicine were continued for 1 month.

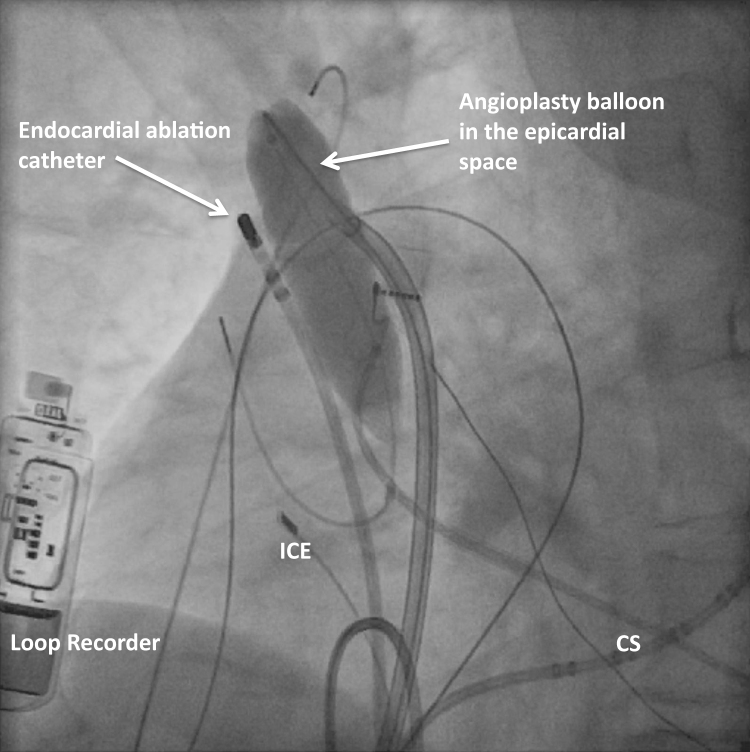

Figure 1.

Left anterior oblique fluoroscopic image showing the inflated angioplasty balloon in the epicardial space to increase the separation between the endocardial ablation catheter and the phrenic nerve. CS = coronary sinus catheter; ICE = intracardiac echocardiography catheter.

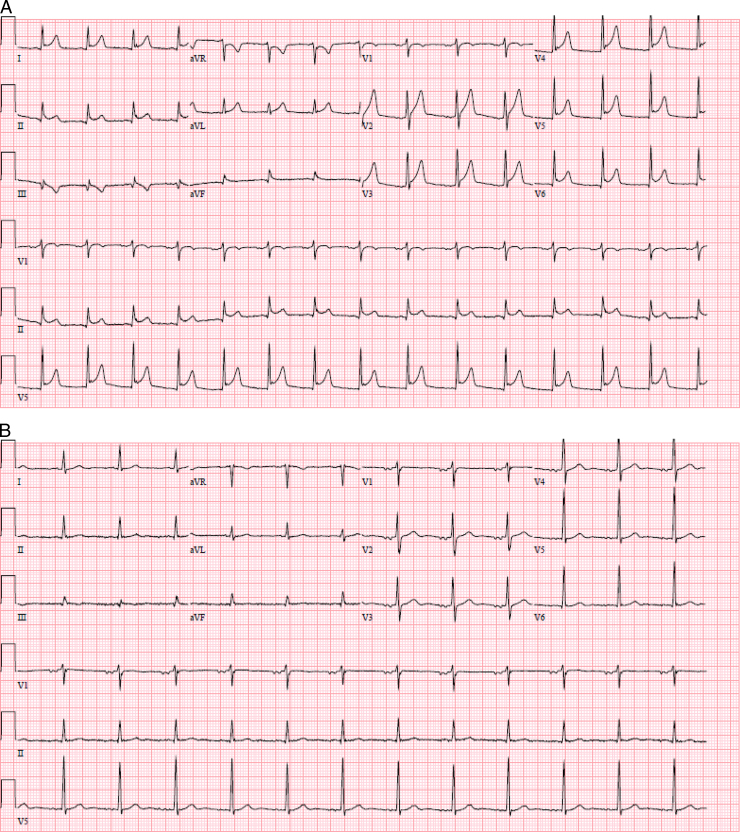

Figure 2.

Electrocardiograms (ECGs). (A) ECG obtained the day after the procedure with diffuse ST-segment elevations in leads I, II, and V2–V6 with ST-segment depression in aVR consistent with acute pericarditis. (B) ECG obtained at the 1-month follow-up visit, demonstrating resolution of the ST-segment elevation.

He was seen in follow-up at 1, 3, and 6 months and with resolution of his symptoms. No ST elevations or findings of chronic pericarditis were noted on electrocardiograms at the follow-up visits. Nine months after the epicardial ablation he returned to the clinic with dyspnea on exertion, abdominal ascites, weight gain, and lower-extremity edema requiring increasing doses of oral bumetanide. The patient was afebrile. Blood work demonstrated a normal white blood cell count, a normal thyroid-stimulating hormone level, a Westergren erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 27 mm/h (upper limit of normal is 25 mm/h), a C-reactive protein of 16 mg/L (upper limit of normal is <5 mg/L), an antinuclear antibody of 1:320 in a speckled pattern, and a negative anti–double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid titer. An echocardiogram revealed normal biventricular function and a stress test showed a maximum workload of 6.3 metabolic equivalents and a hypotensive response to peak exercise. A cardiac magnetic resonance imaging study showed pericardial thickening with concern for constrictive pericarditis (Figure 3). A coronary angiogram and simultaneous left and right heart catheterization demonstrated no coronary artery disease but equalization of diastolic pressures, confirming pericardial constriction (Figure 4). He was taken to the operating room and found to have severe global thickening of the posterior pericardium and moderate thickening of the anterior pericardium, and underwent an uncomplicated endoscopic pericardiectomy. Surgical pathology demonstrated pericardial fibrosis with focal chronic inflammation, including plasma cells (Figure 5). After surgery, his symptoms improved and repeat magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated no pericardial enhancement.

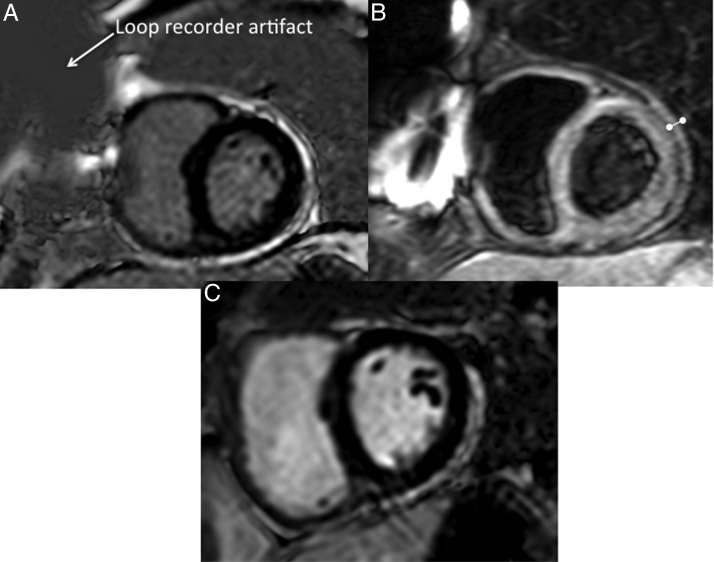

Figure 3.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). (A) Cardiac MRI late gadolinium imaging demonstrating circumferential enhancement of the pericardium, consistent with constriction. (B) Postcontrast T1-weighted black blood image demonstrating thickening of pericardium >6 mm. (C) Follow-up postoperative cardiac MRI with late gadolinium imaging showing decreased enhancement in the pericardium, demonstrating resolution of the constricted pericardium.

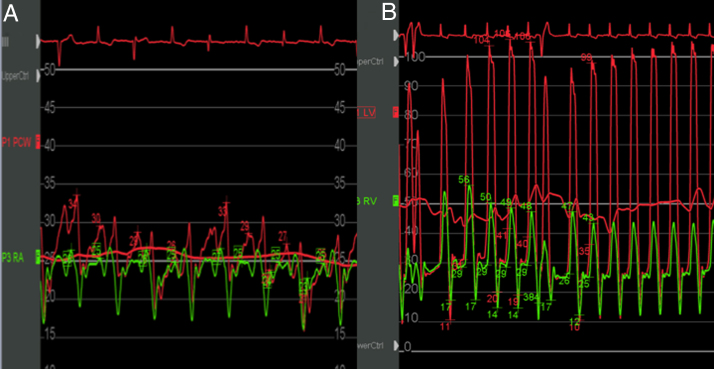

Figure 4.

Simultaneous left and right heart catheterization. (A) Simultaneous pulmonary capillary wedge (red) and right atrial (green) tracings demonstrating the equalization of diastolic pressures and the rapid y descent. (B) Simultaneous left and right heart catheterization pressure tracings demonstrating equalization of diastolic pressures and the classic dip and plateau. The red tracing is the left ventricle and the green tracing is the right ventricle.

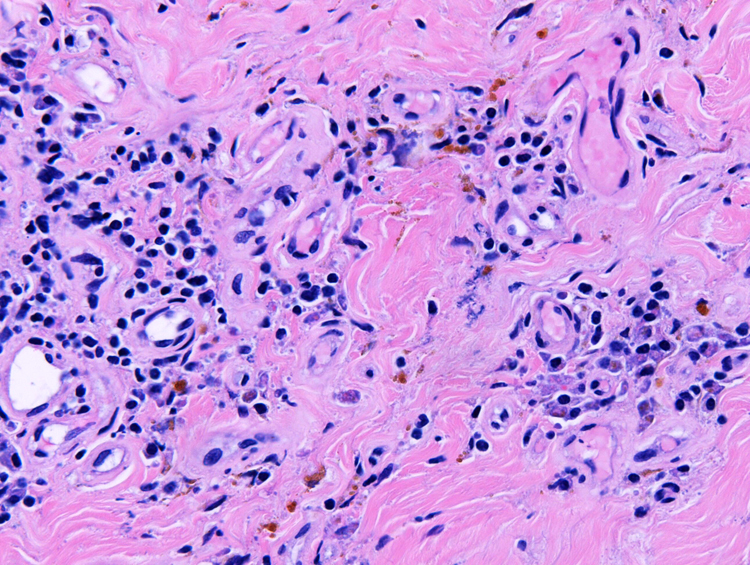

Figure 5.

Pericardial pathology. High-power photomicrograph of pericardium shows fibrosis, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and focal hemosiderin deposits (hematoxylin-eosin stain).

Discussion

This case illustrates that constrictive pericarditis can occur as a late complication after a single percutaneous epicardial ablation procedure and should be included in the differential diagnosis of new-onset heart failure after epicardial ablation. The severity and diffuse nature of the pericardial thickening far exceeded the amount of radiofrequency energy delivered, and it is likely that the patient developed a diffuse reactive pericarditis. Given that using the angioplasty balloon to isolate the phrenic nerve involves a physical displacement of the heart, it is possible that this technique results in more diffuse pericardial inflammation in a similar way to vessel angioplasty.7, 8

A previous occurrence of constrictive pericarditis following endocardial atrial fibrillation ablation has been reported, but the causative relationship is less evident than in procedures with direct pericardial instrumentation.9 The contribution of the endocardial lesions to the pericarditis is uncertain. Given the absence of symptoms for 6 months, it does not appear that he had chronic clinical pericarditis. In the previously published report by Javaheri et al,5 the development of constriction was more probable, given the repeated instrumentation of the pericardial space with 4 epicardial procedures.

Intrapericardial steroids were administered following the procedure as a prophylactic measure. D’Avila et al10 demonstrated in a porcine model that the administration of triamcinolone prevented hemorrhagic pericarditis. The relevance of these findings to human cases requires further investigation. There are data from the cardiothoracic surgery literature that prophylactic colchicine may reduce the incidence of postpericardiotomy syndrome and therefore reduce the incidence of postoperative pericarditis.11, 12 Prophylactic colchicine and systemic corticosteroids both reduce inflammatory markers after pulmonary vein isolation.13, 14 However, the studies examining prophylactic colchicine did not include pericarditis as an outcome and the prophylactic steroid study had no episodes of pericarditis in either the placebo or steroid groups.13, 14 Therefore, it is unclear at this time if there are any prophylactic pharmacologic options to reduce postablation pericarditis. Certainly, additional studies are needed.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of pericardial constriction after a single uncomplicated percutaneous epicardial procedure with ablation limited to the right atrium. As epicardial procedures continue to evolve, it is important to recognize this rare complication.

References

- 1.Boyle N.G., Shivkumar K. Epicardial interventions in electrophysiology. Circulation. 2012;126:1752–1769. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.060327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Della Bella P., Brugada J., Zeppenfeld K., Merino J., Neuzil P., Maury P., Maccabelli G., Vergara P., Baratto F., Berruezo A., Wijnmaalen A.P. Epicardial ablation for ventricular tachycardia: a European multicenter study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:653–659. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.962217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tung R., Michowitz Y., Yu R., Mathuria N., Vaseghi M., Buch E., Bradfield J., Fujimura O., Gima J., Discepolo W., Mandapati R., Shivkumar K. Epicardial ablation of ventricular tachycardia: an institutional experience of safety and efficacy. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sacher F., Roberts-Thomson K., Maury P. Epicardial ventricular tachycardia ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2366–2372. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Javaheri A., Glassberg H.L., Acker M.A., Callans D.J., Goldberg L.R. Constrictive pericarditis presenting as a late complication of epicardial ventricular tachycardia ablation. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:e22–e23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.965236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sosa E., Scanavacca M., d’Avila A., Pilleggi F. A new technique to perform epicardial mapping in the electrophysiology laboratory. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1996;7:531–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1996.tb00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breuss J.M., Cejna M., Bergmeister H. Activation of nuclear factor-ΚB significantly contributes to lumen loss in a rabbit iliac artery balloon angioplasty model. Circulation. 2002;105:633–638. doi: 10.1161/hc0502.102966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buch E., Vseghi M., Cesario D.A., Shivkumar K. A novel method to prevent phrenic nerve injury during catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahsan S.Y., Moon J.C., Hayward M.P., Chow A.W.C., Lambiase P.D. Constrictive pericarditis after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2008;118:e834–835. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.786541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.d’Avila A., Neuzil P., Thiagalingam A., Gutierrez P., Aleong R., Ruskin J.N., Reddy V.Y. Experimental efficacy of pericardial instillation of anti-inflammatory agents during percutaneous epicardial catheter ablation to prevent postprocedure pericarditis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:1178–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imazio M., Trinchero R., Brucato A. Colchicine for the prevention of the post-pericardiotomy syndrome (COPPS): a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2749–2754. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imazio M., Brucato A., Ferrazzi P. Colchicine for the prevention of postpericardiotomy syndrome and postoperative atrial fibrillation: the COPPS-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1016–1023. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deftereos S., Giannopoulos G., Kossyvakis C. Colchicine for prevention of early atrial fibrillation recurrence after pulmonary vein isolation: a randomized controlled study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1790–1796. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koyama T., Tada H., Sekiguchi Y. Prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrence with corticosteroids after radiofrequency catheter ablation: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1463–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]