Abstract

Purpose

To determine the association of different levels of cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), an objective indicator of habitual physical activity, with gallbladder disease.

Methods

In the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study (ACLS) database, 41,528 men and 13,206 women aged 20-90 years, with BMI ≥18.5 and without history of cardiovascular disease and cancer, received a preventive examination at the Cooper Clinic in Dallas, Texas, between 1970 and 2003. CRF was quantified as maximal metabolic equivalents and classified as low, moderate, and high based on traditional ACLS cutpoints. Gallbladder disease was defined as physician-diagnosed gallbladder disease.

Results

When compared with low CRF, adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for gallbladder disease for those with moderate and high CRF were 0.74 (0.55-0.99) and 0.59 (0.42-0.82), respectively when adjusted for all the potential confounders. Each 1 metabolic equivalent increment of CRF was associated with 10% lower odds of gallbladder disease in all participants (P for trend <.001), 13% lower in women (P for trend <.001), and 8% lower in men (P for trend =0.08). The association was consistent across age, history of diabetes mellitus, and physical inactivity subgroups.

Conclusions

CRF is inversely related to the prevalence of gallbladder disease among relatively health men and women in the ACLS cohort.

Keywords: Physical Fitness, Physical Activity, Epidemiology, Gallbladder problems

Introduction

Gallbladder disease is one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal diseases in developed countries. Medical costs are roughly $6.2 billion each year for gallbladder disease in the U.S., and have increased more than 20% during the past 3 decades [1, 2]. Risk factors for gallbladder disease can be classified as immutable and modifiable factors. Known immutable risk factors include female gender, ethnic background, aging, and family history or genetics. Potential modifiable risk factors include obesity, metabolic syndrome, weight gain since early adulthood, rapid weight loss, smoking, diet (animal fats, refined sugars, vegetable fats, and fibers intake), and physical inactivity [1-4].

The role of physical activity in the development of gallbladder disease has recently been investigated in several studies. Most of these studies suggested that physical activity independently decreased the risk of gallbladder disease and might play an important role in the prevention of symptomatic and asymptomatic gallbladder disease [3-11]. However, most studies used self-reported questionnaires to measure physical activity exposure and physical activity outcomes from the various questionnaires have differed. For example, Chuang et al. reported that sport activity, which is vigorous, is more effective than work or leisure-time activity in the prevention of gallstone disease [10]. This indicates that the self-reported physical activity in previous studies might not provide an accurate assessment of the exposure. Cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) is recognized as an objective and reproducible measure that reflects the functional consequences of physical activity habits [12], and may provide better evidence with which to evaluate associations with gallbladder disease. The National Runners’ Health Study has identified low CRF as one of the risk factors for gallbladder disease and suggested that CRF is inversely associated with gallbladder disease after controlling for different physical activity levels [13]. However, the study used self-reported 10 km race performance as the indicator of CRF. Another small sample study reported that aerobic capacity (measured by Åstrand submaximal exercise) was not significantly different between women with cholelithiasis and women who were healthy [14]. Therefore, in the present study, we examined the prevalence of gallbladder disease across levels of CRF, objectively measured by maximal treadmill exercise test, based on the database of the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study (ACLS). Our hypothesis is that a higher level of CRF will be associated with lower prevalence of gallbladder disease.

Material and Methods

Study design and subjects

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of participants from the ACLS and examined the association between gallbladder disease and CRF. There were 51,428 men and 17,777 women, aged 20 to 90 years, who received a preventive medical examination at the Cooper Clinic in Dallas, Texas, between 1970 and 2003. Exclusion criteria included history of cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction (n=601) or stroke (n=142)), cancer (n=1777), underweight (body mass index (BMI) <18.5) or missing BMI data (n=6986), abnormal electrocardiography results during rest or exercise (n=3886), or failure to achieve at least 85% of age-adjusted maximal heart rate on the treadmill exercise test (n=1079). The final sample contains 41,528 men and 13,206 women for analysis. More than 95% of participants were white and employed or previously employed in professional occupations. The main assessments included self-reported medical history, clinical examination, and maximal treadmill exercise test. The ACLS was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Cooper Institute and all participants provided written consent prior to the examination.

Self-reported medical history

Standardized medical history questionnaires were used to collect information on demographic characteristics, medical history, and diet and physical activity habits. Hypertension was defined as physician diagnosis or blood pressure >140/90 mmHg. Diabetes mellitus was defined as physician diagnosis, insulin use, or fasting glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as physician diagnosis or total cholesterol ≥6.2 mmol/L. Smoking habits (whether a current smoker or non-smoker), alcohol intake (heavy drinker was defined as alcohol drinks >14 per week for men or >7 per week for women), dietary restrictions (low fat or low cholesterol diet), and physical inactivity were self-reported from the medical questionnaire. Physical inactivity was defined as no leisure-time physical activity in the past 3 months.

Gallbladder disease, the outcome variable, was defined by participants’ self-reports. Participants were asked to indicate whether they ever had physician-diagnosed gallbladder disease. If their response was “Yes”, the outcome was coded 1; otherwise, the outcome was coded 0 for analysis.

Clinical examinations

Clinical examinations included anthropometry measurements, blood pressure measurements, and fasting blood chemistry analyses for glucose and total cholesterol. BMI was calculated as measured weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. All the examination procedures and methods followed a standard manual of operations and have been described in prior reports [15].

Cardiorespiratory fitness

CRF was measured by maximal treadmill exercise test using a modified Balke protocol, as previously described [12]. In brief, for the first 25 minutes, the treadmill speed was 88m·min−1, with a grade of 0% for the first minute, a grade of 2% for the second minute, and an increase of 1% each minute thereafter. After 25minutes, the grade did not change, but speed was increased 5.4 m·min−1 until the test was ended. Participants were encouraged to do a maximal effort to reach at least 85% of their age-predicted maximum heart rate (220 minus age in years). To standardize exercise performance, we showed CRF as maximal metabolic equivalents (METs, 1 MET=3.5 mL of O2 uptake/kg/min) estimated from the final treadmill speed and grade [16].

CRF was classified as low, moderate, and high based on the cutpoints developed from the ACLS [17]. These cutpoints were derived from age-and sex-specific distributions of treadmill time duration among the ACLS population, as we published previously [17]. Because there are no current standard cut points to categorize low, moderate, or high CRF, to maintain consistency in our study methods, we used this approach in the ACLS.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were done using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics 22). Differences in variables among the three groups of CRF were evaluated by ANOVA for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) across the CRF levels while controlling for potential confounders. The low CRF group was used as the reference category while calculating aOR. Crude-adjusted models controlled for age (year), sex, and examination year. Multivariable-adjusted models controlled for age (year), sex, examination year, BMI (kg/m2), and the following binary (yes or no) variables: physical inactivity, current smoker, heavy drinking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and low fat or low cholesterol diet. We tested for the statistical interaction between sex and CRF with the prevalence of gallbladder disease and found no significant interaction (Wald Chi-square test: P=.81). Therefore, this paper presents the results for the overall population. However, to maintain consistency and facilitate comparisons with other studies [4, 13], we have provided the results for men and women separately in the supplemental files (Supplemental Table S1, S2 and S3, Supplemental Figure S1 and S2). Finally, we stratified the sample across categories of age (age ≥ 55 or < 55), diabetes status, and physical inactivity to assess the consistency of the association between CRF and gallbladder disease among subgroups. All P values were two-sided, and P < .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The descriptive statistics across CRF levels are shown in Table 1. BMI, the percentage of current smokers, physical inactivity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia were incrementally lower across the CRF levels (P<.001). The percentage of heavy drinking, and low fat and low cholesterol dietary restriction were incrementally higher across the CRF levels (P<.001).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the overall study population across cardiorespiratory fitness groups: Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study, 1970-2003

| Cardiorespiratory Fitnessa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | All (N=54,734), mean (SD) or % | Low (N =8,340), mean (SD) or % | Moderate (N=21,153), mean (SD) or % | High (N =25,241), mean (SD) or % | P value |

| Age, yr | 43.3 (9.5) | 42.3 (8.9) | 43.4 (9.4) | 43.5 (9.9) | <.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.7 (4.1) | 29.0 (5.5) | 26.2 (3.7) | 24.3 (2.9) | <.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.4 (1.1) | 5.6 (1.1) | 5.5 (1.0) | 5.2 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 5.5 (3.3) | 5.7 (1.3) | 5.5 (0.9) | 5.4 (4.7) | <.001 |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | |||||

| Systolic | 119 (14) | 123 (14) | 120 (14) | 118 (14) | <.001 |

| Diastolic | 81 (10) | 83 (10) | 81 (10) | 78 (9) | <.001 |

| Current smoker, % | 15.6 | 27.9 | 18.4 | 9.2 | <.001 |

| Heavy drinking, % | 7.8 | 5.4 | 7.2 | 9.0 | <.001 |

| Physical inactivity, % | 31.5 | 65.2 | 39.7 | 13.4 | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus,(% | 4.5 | 8.4 | 4.8 | 2.9 | <.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 27.2 | 40.0 | 29.4 | 21.1 | <.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, % | 25.7 | 32.8 | 28.4 | 21.1 | <.001 |

| Low fat dietary restriction, % | 8.3 | 4.6 | 6.8 | 10.9 | <.001 |

| Low cholesterol dietary restriction, % | 5.5 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 7.2 | <.001 |

BMI=body mass index; MET=metabolic equivalent; SD=standard deviation.

P value: ANOVA test for continuous variables or Chi-square tests for categorical variables across three fitness groups.

Cardiorespiratory fitness was classified as low, moderate, and high based on cutpoints developed from age- and sex-specific distributions of treadmill time duration among the ACLS population[17].

The associations between CRF and the prevalence of gallbladder disease are presented in Table 2. The prevalence of gallbladder disease was 1.10%, 0.87%, and 0.79% among those with low, moderate, and high levels of CRF, respectively (P=.03). Controlled for age, sex, and examination year, CRF was significantly and inversely associated with the prevalence of gallbladder disease (P for trend <.001) as determined by logistic regression analysis (Model 1). When compared with low CRF, aORs (95% CIs) for gallbladder disease for those with moderate and high CRF were 0.53 (0.41-0.69) and 0.39 (0.31-0.51), respectively (Model 1). Adding BMI, physical inactivity, current smoker, heavy drinking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and low fat and low cholesterol dietary restriction to the model did not change the significant trend, but did attenuate the association between CRF and the prevalence of gallbladder disease. Similar associations were observed for men and women (Supplemental Table S3), but did not reach statistical significance in men (P=.07). In the fully adjusted model (Model 2), when compared with low CRF, all participants with moderate and high CRF had 26% and 41% lower gallbladder disease odds respectively (Table 2, P=.002); When separated by sex, women with moderate and high CRF had 31% and 49% lower gallbladder disease risk, respectively, than did women with low CRF (Supplemental Table S3, P=.005), and men had 24% and 36% lower gallbladder disease risk, respectively (Supplemental Table S3, P=.07).

Table 2.

Prevalence and adjusted odds ratios for gallbladder disease by cardiorespiratory fitness levels among 54,734 participants

| OR (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases/N | Prevalence | Model 1a | Model 2b | |

| Low CRF | 92/8,340 | 1.10% | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate CRF | 184/21,153 | 0.87% | 0.53 (0.41-0.69) | 0.74 (0.55-0.99) |

| High CRF | 200/25,241 | 0.79% | 0.39 (0.31-0.51) | 0.59 (0.42-0.82) |

| P for linear trend | .03 | <.001 | .002 | |

Adjusted for age, sex, and examination year.

Adjusted for age, sex, examination year, body mass index, physical inactivity, current smoker, heavy drinking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, low fat dietary restriction, and low cholesterol dietary restriction.

We also examined the association between the prevalence of gallbladder disease and CRF, with METs represented as a continuous variable. Fully-adjusted OR (95% CI) associated with each MET increment was 0.90 (0.84-0.96; P=.001) for all participants, 0.92 (0.84-1.01; P=.08) for men, and 0.87 (0.79-0.95; P=.003) for women.

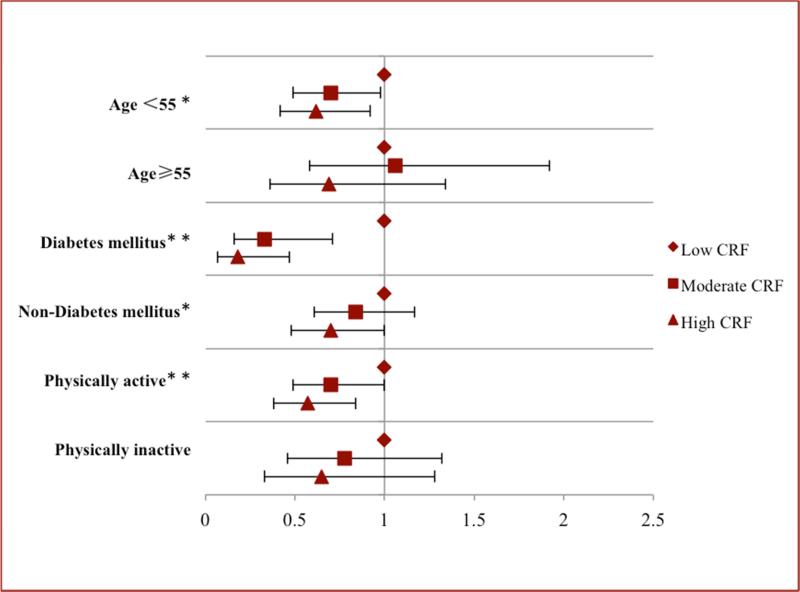

Finally, the generally inverse association between CRF and the prevalence of gallbladder disease were similar across subgroups when participants were categorized by age, diabetes mellitus status, and physical inactivity (Figure 1). A similar pattern of the inverse association between CRF and gallbladder disease was observed in both sexes, although not all comparisons were statistically significant in men (Supplemental Figure S1) and women (Supplemental Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Multivariablea aORs (95% CIs) of gallbladder disease stratified by CRF and age, diabetes mellitus, and physical activity; aAdjusted for age, sex, examination year, body mass index, physical inactivity, current smoker, heavy drinking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, low fat dietary restriction, and low cholesterol dietary restriction. * P for linear trend < .05; **P for linear trend < .01. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. aOR=adjusted odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; CRF=cardiorespiratory fitness.

Discussion

There are three key findings from the current study. First, CRF was inversely associated with the prevalence of gallbladder disease after extensive control for confounding factors including age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI, physical activity, chronic condition, and diet information. The general pattern of association was for substantially lower relative odds of gallbladder disease with moderate (26%) and high (41%) levels of CRF. We found that each 1-MET increase of CRF was associated with 10% lower odds of gallbladder disease. Second, we observed a consistent inverse gradient between CRF and gallbladder disease in both men and women. Each 1-MET increase in CRF was associated with 13% lower odds of gallbladder disease for women, and 8% lower odds for men. Third, the pattern of the association between CRF and the prevalence of gallbladder disease was similar across subgroups of age, diabetes mellitus status, and physical inactivity.

To our knowledge, only two previous studies have assessed the relationship between CRF and gallbladder disease. In the National Runners’ Study, which included 29,110 men and 11,953 women [13], Williams et al. found that greater CRF, assessed by self-reported 10 km race speed, was inversely related to the risk for self-reported gallstones. Compared to the least fit men and women, men who ran faster than 4.75 m/s had 83% lower risk and women who ran faster than 4 m/s had 93% lower risk. Our cross-sectional study confirmed this finding. However, Celikagi et al. [14] recently reported that objectively measured maximal aerobic capacity from the Astrand submaximal exercise protocol was not significantly different between 30 female patients with cholelithiasis (VO2max in ml/kg/min: 21.2±6.3) and 30 healthy controls women (VO2max in ml/kg/min: 22.3±4.4) (P=.55).

The previous studies that examined the relationship between physical activity and gallbladder disease have yielded inconsistent findings. Some earlier studies reported no association between physical activity and gallbladder disease, [18-21] while most studies found a significant inverse association [3-11]. The Strong Heart Study [4] used ultrasonography to examine the role of physical activity in the development of gallbladder disease in American Indians, a population at high risk for gallbladder disease. This study suggested that physical activity was associated with a decreased risk of developing symptomatic and asymptomatic gallbladder disease. In addition, they observed a significant relationship between physical activity level and gallbladder disease development in those without baseline diabetes [4], but not in those with. In the present study we found a significant relationship between CRF level and gallbladder disease in those with diabetes mellitus in both sexes (Supplemental Figure S1 and S2). The reason for this difference is unclear; however, the previous study measured physical activity by self-report while the present study used objectively measured CRF. Another follow-up study from European Prospective Investigation of Cancer, which included 25,639 volunteers aged 40-74 years [6], reported that the highest level of physical activity was associated with a 70% lower risk of symptomatic gallstones than the lowest level after 5 years follow-up. These findings suggest that physical activity might provide a protective effect against gallbladder disease. However, the Harvard University Alumni Health Study [19] reported that physical activity appeared to be unrelated to risk of developing gallbladder disease in men, based on physical activity and self-reported gallbladder disease outcomes. In this study, participants were younger than in the other studies and the follow-up time was longer. Data have shown that inverse associations between physical activity and symptomatic gallstones are attenuated after 14 years, compared with 5-year follow-up [6], so the reason for the discrepancy in results might be due to the different length of follow-up. Our overall finding is consistent with the studies that found an inverse association between physical activity and gallbladder diseases. The inconsistency of results across the existing literature may be due to factors related to different populations, follow-up duration, outcome assessment, or exposure measurements from self-report PA questionnaire to objectively measured CRF.

The mechanisms by which physical activity may influence the pathogenesis of gallbladder are poorly understood. An animal study of exercise and a lithogenic diet reported that 12 weeks of endurance exercise training attenuated gallstone development when compared to a sedentary group and suggested that the mechanism may lie in the change gene expression related to cholesterol metabolism to improve cholesterol clearance from the circulation [22]. Other studies reported that physical activity might prevent gallstone formation by decreasing biliary cholesterol secretion, changing some gallbladder regulatory hormones, and enhancing the motility of gastrointestinal tract and gallbladder [13, 23]. As obesity, high glucose, high insulin, hypertension, and high triglycerides are known risk factors for gallbladder disease, physical activity or exercise may favorably change these factors and play a mediated role in the prevention of gallbladder disease [24].

A major strength of our study is the use of objectively measured CRF, which is reliable and reproducible, that allowed us to accurately reflect the relationship between CRF and gallbladder disease. One of the major limitations of the current study is the cross-sectional design, which limited our ability to make causal inference between CRF and gallbladder disease. Also, because the participants were primarily white, well-educated, and with middle to upper socioeconomic status, the results may not be generalizable to other populations. The prevalence of gallbladder disease was 2% for women and 0.5% for men in the ACLS cohort. These rates are much lower than the national data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) [25], in which the prevalence for white Americans was 16.6% in women and 8.6% in men. One reason for the difference might be due to the characteristics of the ACLS population. In addition, gallbladder disease was determined by ultrasonography in NHANES III, whereas we collected the information through clinical questionnaires, which might have the potential to underestimate the prevalence of gallbladder disease. However, the homogeneity of our sample strengthens the internal validity of the results by reducing potential confounding. The non-significant findings between CRF and gallbladder disease for men might relate to a lower prevalence of disease than we observed in women. We did not have enough power to detect a statistically significant difference in prevalence across CRF levels in men, but we did find an inverse trend in our results (P=.07). A second limitation is that data on daily intake of nutrients data were insufficient, including only crude information on alcohol intake, fat, and cholesterol dietary restriction that were used in the logistic regression model. Third,, the outcome variable of gallbladder disease was obtained from self-reported medical history. The self-report nature is likely associated with misclassification of the study outcome. Finally, the study population included a very limited number of participants who developed incident case of gallbladder disease. Future longitudinal studies are needed to further clarify the associations between objectively measured CRF (or physical activity) and incident gallbladder disease based on ultrasound-diagnosis with an adequate sample size of men and women.

Conclusions

CRF is inversely related to the prevalence of gallbladder disease among men and women without history of CVD and cancer in the ACLS cohort. A higher level of CRF was associated with lower prevalence of gallbladder disease. Although 20-40% of CRF is determined by genetic factors, it has been shown that CRF can be increased by regular exercise as little as 72 min·wk−1 of moderate-intensity activity [26]. Therefore, meeting the current the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans [27] (at least 150 min·wk−1 of moderate-intensity physical activity) will not only improve CRF levels, but may also provide some protection against gallbladder disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK088195. Changqing Li was supported by a Chinese Government Scholarship. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Chinese Government.

The authors thank the Cooper Clinic physicians and technicians for collecting the baseline data and Cooper Institute staff for data entry and management.

We appreciate Gaye Christmus for her editorial contribution to the manuscript.

List of abbreviations

- ACLS

Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study

- aOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CRF

Cardiorespiratory fitness

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- MET

Metabolic equivalent

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Shaffer EA. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology of gallbladder stone disease. Best Pract Res Cl Ga. 2006;20(6):981–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut and liver. 2012;6(2):172–87. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misciagna G, Centonze S, Leoci C, Guerra V, Cisternino AM, Ceo R, et al. Diet, physical activity, and gallstones - a population-based, case-control study in southern Italy. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(1):120–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kriska AM, Brach JS, Jarvis BJ, Everhart JE, Fabio A, Richardson CR, et al. Physical activity and gallbladder disease determined by ultrasonography. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(11):1927–32. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3181484d0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato I, Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH. Prospective study of clinical gallbladder disease and its association with obesity, physical activity, and other factors. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37(5):784–90. doi: 10.1007/BF01296440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banim PJR, Luben RN, Wareham NJ, Sharp SJ, Khaw KT, Hart AR. Physical activity reduces the risk of symptomatic gallstones: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Gastroen Hepat. 2010;22(8):983–8. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32833732c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofmann AF. Recreational physical activity and the risk of cholecystectomy in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(3):213–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leitzmann MF, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Spiegelman D, Wing AL, et al. The relation of physical activity to risk for symptomatic gallstone disease in men. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(6):417. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-6-199803150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storti KL, Brach JS, FitzGerald SJ, Zmuda JM, Cauley JA, Kriska AM. Physical activity and decreased risk of clinical gallstone disease among post-menopausal women. Prev Med. 2005;41(3-4):772–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chuang CZ, Martin LF, LeGardeur BY, Lopez A. Physical activity, biliary lipids, and gallstones in obese subjects. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(6):1860–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hou L, Shu XO, Gao YT, Ji BT, Weiss JM, Yang G, et al. Anthropometric measurements, physical activity, and the risk of symptomatic gallstone disease in Chinese women. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(5):344–50. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sui XM, Lee DC, Matthews CE, Adams SA, Hebert JR, Church TS, et al. Influence of Cardiorespiratory Fitness on Lung Cancer Mortality. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(5):872–8. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c47b65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams PT. Independent effects of cardiorespiratory fitness, vigorous physical activity, and body mass index on clinical gallbladder disease risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(9):2239–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Celikagi C, Genc A, Bal A, Ucok K, Turamanlar O, Ozkececi ZT, et al. Evaluation of daily energy expenditure and health-related physical fitness parameters in patients with cholelithiasis. Eur J Gastroen Hepat. 2014;26(10):1133–8. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Earnest CP, Artero EG, Sui X, Lee DC, Church TS, Blair SN. Maximal estimated cardiorespiratory fitness, cardiometabolic risk factors, and metabolic syndrome in the aerobics center longitudinal study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(3):259–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 7th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore (MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sui XM, LaMonte MJ, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness and risk of nonfatal cardiovascular disease in women and men with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20(6):608–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorgensen T, Jensen KH. Polyps in the Gallbladder - a Prevalence Study. Scand J Gastroentero. 1990;25(3):281–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahi T, Paffenbarger RS, Jr., Hsieh CC, Lee IM. Body mass index, cigarette smoking, and other characteristics as predictors of self-reported, physician-diagnosed gallbladder disease in male college alumni. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(7):644–51. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kono S, Shinchi K, Todoroki I, Honjo S, Sakurai Y, Wakabayashi K, et al. Gallstone Disease among Japanese Men in Relation to Obesity, Glucose-Intolerance, Exercise, Alcohol-Use, and Smoking. Scand J Gastroentero. 1995;30(4):372–6. doi: 10.3109/00365529509093293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jorgensen T. Gall stones in a Danish population. Relation to weight, physical activity, smoking, coffee consumption, and diabetes mellitus. Gut. 1989;30(4):528–34. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.4.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilund KR, Feeney LA, Tomayko EJ, Chung HR, Kim K. Endurance exercise training reduces gallstone development in mice. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(3):761–5. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01292.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Utter A, Goss F. Exercise and gall bladder function. Sports Med. 1997;23(4):218–27. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199723040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters HPF, De Vries WR, Vanberge-Henegouwen GP, Akkermans LMA. Potential benefits and hazards of physical activity and exercise on the gastrointestinal tract. Gut. 2001;48(3):435–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, Maurer KR. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(3):632–9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Church TS, Earnest CP, Skinner JS, Blair SN. Effects of different doses of physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness among sedentary, overweight or obese postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;297(19):2081–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.19.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans In. 2008 http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.