Abstract

AIM

To assess the correlation between the send-out enzyme-linked immuno sorbent assay (ELISA) and the point-of-care (POC) calprotectin test in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients.

METHODS

We prospectively collected stool samples in pediatric IBD patients for concomitant send-out ELISA analysis and POC calprotectin testing using the Quantum Blue® (QB) Extended immunoassay. Continuous results between 17 to 1000 μg/g were considered for comparison. Agreement between the two tests was measured by a Bland-Altman plot and statistical significance was determined using Pitman’s test.

RESULTS

Forty-nine stool samples were collected from 31 pediatric IBD patients. The overall means for the rapid and ELISA tests were 580.5 and 522.87 μg/g respectively. Among the 49 samples, 18 (37.5%) had POC calprotectin levels of ≤ 250 μg/g and 31 (62.5%) had levels > 250 μg/g. Calprotectin levels ≤ 250 μg/g show good correlation between the two assays. Less correlation was observed at quantitatively higher calprotectin levels.

CONCLUSION

In pediatric IBD patients, there is better correlation of between ELISA and POC calprotectin measurements at clinically meaningful, low-range levels. Future adoption of POC calprotectin testing in the United States may have utility for guiding clinical decision making in real time.

Keywords: Calprotectin, Stool biomarker, Inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, Point-of-care test

Core tip: Quantitative fecal calprotectin (FC) measurements, particularly in children affected by inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), is an important element of disease monitoring in a patient population vulnerable to repeated endoscopic confirmation of mucosal healing. In the United States, rapid FC assays are not yet Food and Drug Administration approved, and send-out FC assays require processing delay, preventing point-of-care usefulness. The significance of our findings in this study reiterate the clinical utility of the point-of-care FC testing in children with IBD, who are at-risk for subclinical mucosal-level inflammation. Our study confirms good correlation between the send-out and rapid point-of-care FC tests at the clinically-meaningful target range (≤ 250 μg/g) associated with endoscopic remission.

INTRODUCTION

Reliable mucosal-level monitoring of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is important for appropriate disease management response. Although endoscopy remains the current gold standard for mucosal-level evaluation, the invasive nature, anesthesia requirement, and potential for procedure-related complications including bowel perforations are valid considerations for pediatric IBD patients to be disease-monitored using non-invasive stool biomarkers[1].

As the strength of evidence for longitudinally monitoring IBD using serial calprotectin measurements is emerging, most clinical laboratories in the United States do not analyze fecal calprotectin in-house and require quantification via a send-out method. As a result, calprotectin measurement by the traditional enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can be time intensive, potentially leading to delays in clinical decision-making - especially in children with IBD who may have discordance of biochemical markers (e.g., CRP) with subjective assessments of disease activity (e.g., abdominal pain).

Rapid fecal calprotectin testing, using immunochromatographic assays, could overcome this time delay and can result in point-of-care (POC) calprotectin measurements within minutes. One POC test - Quantum Blue® Extended immunoassay (Bühlmann Laboratories, Switzerland) - is approved for clinical use in Europe, Canada, and countries in Asia and South America. While there are a few studies showing good correlation of this particular assay with an ELISA test in mainly an adult, IBD and non-IBD cohort[2,3], there is only one European study to our knowledge assessing the strength of correlation for POC testing with the standard ELISA in children with IBD. In the United States, POC calprotectin testing is not yet Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved at this time for clinical use[4]. We aimed to assess the correlation between the send-out ELISA and the POC calprotectin test in pediatric IBD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a Stanford University IRB approved prospective study conducted from October 2014 to May 2015. In previously diagnosed pediatric IBD patients who were being assessed for routine fecal calprotectin levels, their tested stool sample was also analyzed for calprotectin using the Quantum Blue® POC test. Informed consent by the parent or legal guardian was required for participation. During standard of care inpatient and outpatient encounters, fecal samples were collected from patients by our hospital laboratory for processing and sent to one centralized laboratory for ELISA analysis (Genova Diagnostics, NC, United States). No samples were collected from patients undergoing colonic cleanout. ELISA results were reported back within 10-14 d as μg/g within a continuous range of < 17 to 2500 μg/g. Results > 1000 were recorded as 1000 to match the range of the POC calprotectin test.

For POC calprotectin testing, stool samples (1 g) were extracted using the CALEX® cap device by unscrewing the cap and inserting it into the stool sample. The collection stick was removed with 1 g of adhering stool and inserted into the collection container that contained the antibody reagent. The device was then vigorously homogenized using a vortex mixer, and 60 μL of the mixed sample was placed in the QB test cartridge and loaded into the reader. After 12 min, the test cartridge was read and displayed the amount of FC present in the sample. The results were reported as μg/g with a continuous range of < 30 to 1000 μg/g. From stool extraction to results, the test required approximately 15 min to complete.

Previous studies and clinical experience have indicated that calprotectin ≤ 250 μg/g correlates with lower disease activity at the mucosal-level on endoscopic evaluation[5-7]. Therefore, we were particularly interested in the strength of correlation between the ELISA and POC calprotectin test within this lower range of values. Agreement between the two tests was measured by a Bland-Altman plot and statistical significance was determined using Pitman’s test in STATA 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States).

RESULTS

From routine inpatient or outpatient care, 49 stool samples were collected from 31 pediatric IBD patients (Table 1). The overall means for the rapid and ELISA tests were 580.5 μg/g and 522.87 μg/g respectively. Among the 49 samples, 18 (37.5%) had POC calprotectin levels of ≤ 250 μg/g and 31 (62.5%) had levels > 250 μg/g.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics n (%)

| Total (%) | FC ≤ 250 μg/g | FC > 250 μg/g | |

| Samples | 49 | 21 (43) | 28 (57) |

| Age (yr) | 12.8 | 13.3 | 12.4 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| CD | 21 (43) | 9 (43) | 12 (43) |

| UC | 22 (45) | 10 (48) | 12 (43) |

| IBD-U | 6 (12) | 2 (9) | 4 (14) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 24 (49) | 8 (38) | 16 (57) |

| Female | 25 (51) | 13 (62) | 12 (43) |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 2.29 | 1.12 | 3.31 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 25.54 | 13.09 | 34.23 |

CD: Crohn’s disease; UC: Ulcerative colitis; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; IBD-U: IBD-unclassified; FC: Fecal calprotectin; CRP: C-reactive protein.

Among samples resulting in ≤ 250 μg/g, mean calprotectin levels were 74.1 μg/g from the ELISA and 86.2 μg/g from the POC calprotectin, a mean difference of 12.0 μg/g. Among samples resulting in > 250 μg/g, mean calprotectin levels were 783.5 μg/g from the ELISA and 867.6 μg/g from the POC calprotectin test, a mean difference between of 84.1 μg/g.

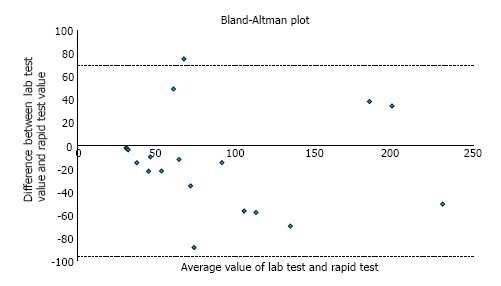

In order to test whether these differences were significant, we used a Bland-Altman plot, graphing the difference between the two test values against their mean value (Figure 1). Pitman’s test was used to determine if there was a correlation between the two values.

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman plot for calprotectin values ≤ 250 μg/g. Pitman’s test showed r = 0.072, with the value close to zero indicating good concordance between the two tests (P = 0.779).

For values ≤ 250 μg/g, Pitman’s test showed r = 0.072, with the value close to zero indicating good concordance between the two tests; further, P = 0.779, confirming that we cannot reject the null hypothesis of equal variances. For values > 250 μg/g (not graphed), the r = 0.109, suggesting that higher absolute values have less correlation between ELISA and POC tests, although the test of significance supported the null hypothesis P = 0.564.

DISCUSSION

Our prospective cohort study showcases the reliability of a POC calprotectin test that is currently being used in routine clinical care in Europe and Canada but not yet approved in the United States. While we acknowledge the limited sample size, the data from our study show good correlation between send-out ELISA and POC calprotectin tests. We show that agreement between the two tests appears to be stronger for lower values - a finding that is corroborated by Kolho et al[8] in a pediatric IBD cohort. Of note, our investigation used a classical statistical method in the Bland-Altman plot which descriptively and quantitatively showcases the strength of correlation between the two tests.

Our results also agree with previous studies that showed increased inter-test variability at higher calprotectin levels - with greater divergence from expected values above 250 μg/g[9,10]. In order to optimize the utility of our study despite our limited sample size, we focused our analysis around values ≤ 250 μg/g since literature in IBD cohorts supports endoscopic disease quiescence at or below 300 μg/g cut-off level. Targeting low-range levels appear to be the clinical goal in calprotectin monitoring.

We also found that values of the POC test were overall higher than the values obtained from ELISA, although the Pitman’s tests indicate that this difference was not statistically significant. Several previous studies from Europe and Asia demonstrate excellent correlation of a rapid assay similar to the one used in this study to ELISA[8,11], but they do not showcase the differential strength of correlation at low vs high calprotectin levels.

In summary, we present the first correlation study of rapid POC calprotectin testing in a pediatric IBD cohort in the United States. Unlike the conventional send-out ELISA which typically takes 10-14 d to result, the future clinical use of POC calprotectin could improve the utility in the decision-making process if levels were available at or near the time of actual care.

COMMENTS

Background

Rapid fecal calprotectin (FC) assays are useful for point-of-care decision making in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly in children. Within-patient correlation data between send-out and rapid point-of-care FC tests are incomplete in pediatric IBD.

Research frontiers

Repeated measurements of low FC in patients with IBD are associated with endoscopic remission, although more data are necessary to confirm optimal cut-off levels for different patients with various IBD subtypes. A target range of ≤ 250 μg/g is often used in clinical practice.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This study confirms good correlation between the send-out and rapid point-of-care FC tests at the clinically-meaningful target range (≤ 250 μg/g) associated with endoscopic remission.

Applications

Ensuring low levels of FC using the rapid point-of-care FC assay in children affected by IBD appear to be reliable and useful in clinical practice.

Peer-review

This is a well done prospective study about the comparison of two types of fecal calprotectin diagnostic methods as possible markers for assessment the pediatric IBD disease severity.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study had IRB approval from Stanford University.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent and assent forms were obtained prior to patient enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: K T Park has served as consultant for Inova Diagnostics and received research support from BUHL MANN Laboratories.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of Origin: United States

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: May 27, 2016

First decision: July 22, 2016

Article in press: January 18, 2017

P- Reviewer: Freeman HJ, Homan M, Posovszky C, Wedrychowicz A S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Canani RB, de Horatio LT, Terrin G, Romano MT, Miele E, Staiano A, Rapacciuolo L, Polito G, Bisesti V, Manguso F, et al. Combined use of noninvasive tests is useful in the initial diagnostic approach to a child with suspected inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:9–15. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000187818.76954.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coorevits L, Baert FJ, Vanpoucke HJ. Faecal calprotectin: comparative study of the Quantum Blue rapid test and an established ELISA method. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51:825–831. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sydora MJ, Sydora BC, Fedorak RN. Validation of a point-of-care desk top device to quantitate fecal calprotectin and distinguish inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagerberg UL, Lööf L, Lindholm J, Hansson LO, Finkel Y. Fecal calprotectin: a quantitative marker of colonic inflammation in children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:414–420. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31810e75a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sipponen T, Savilahti E, Kärkkäinen P, Kolho KL, Nuutinen H, Turunen U, Färkkilä M. Fecal calprotectin, lactoferrin, and endoscopic disease activity in monitoring anti-TNF-alpha therapy for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1392–1398. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guardiola J, Lobatón T, Rodríguez-Alonso L, Ruiz-Cerulla A, Arajol C, Loayza C, Sanjuan X, Sánchez E, Rodríguez-Moranta F. Fecal level of calprotectin identifies histologic inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical and endoscopic remission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1865–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolho KL, Turner D, Veereman-Wauters G, Sladek M, de Ridder L, Shaoul R, Paerregaard A, Amil Dias J, Koletzko S, Nuti F, et al. Rapid test for fecal calprotectin levels in children with Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:436–439. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318253cff1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burri E, Manz M, Rothen C, Rossi L, Beglinger C, Lehmann FS. Monoclonal antibody testing for fecal calprotectin is superior to polyclonal testing of fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin to identify organic intestinal disease in patients with abdominal discomfort. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;416:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malícková K, Janatková I, Bortlík M, Komárek V, Lukás M. [Calprotectin levels in patients with idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease comparison of two commercial tests] Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 2008;57:147–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue K, Aomatsu T, Yoden A, Okuhira T, Kaji E, Tamai H. Usefulness of a novel and rapid assay system for fecal calprotectin in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1406–1412. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]