Abstract

Stress-induced neural injuries are closely linked to the pathogenesis of various neuropsychiatric disorders and psychosomatic diseases. We and others have previously demonstrated certain protective effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) in stress-induced cerebral impairments, but the underlying protective mechanisms still remain poorly elucidated. Here we provide evidence to support the possible involvement of PKCα and ERK1/2 signaling pathways in EGCG-mediated protection against restraint stress-induced neural injuries in rats. In both open-field and step-through behavioral tests, the restraint stress-induced neuronal impairments were significantly ameliorated by administration of EGCG or green tea polyphenols (GTPs), which was associated with a partial restoration of normal plasma glucocorticoid, dopamine and serotonin levels. Furthermore, the stress-induced decrease of PKCα and ERK1/2 expression and phosphorylation was significantly attenuated by EGCG and to a less extent by GTP administration. Additionally, EGCG supplementation restored the production of ATP and the expression of a key regulator of cellular energy metabolism, the peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), in stressed animals. In conclusion, PKCα and ERK1/2 signaling pathways as well as PGC-1α-mediated ATP production might be involved in EGCG-mediated protection against stress-induced neural injuries.

Keywords: epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), stress, protein kinase C α (PKCα), extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 (ERK1/2), peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1 α (PGC-1α)

Introduction

Intensive and prolonged stress can dampen the risk of many health problems including neuropsychiatric disorders (McEwen. 2008; Obradovic and Boyce. 2009; Franklin et al. 2012), malignant cancer, heart diseases, diabetes, obesity, and gastrointestinal disorders (Brindley et al. 1989; Pike and Smith 1997). Because of predominant roles of the central nervous system (CNS) in whole-body stress responses, the study of stress-induced cerebral damages has recently become one of the hot topics in neuroscience. Previously, we demonstrated that psychological stress induced a series of disorders in the CNS, such as impaired behavioral performances, excessive productions of stress hormones and stress-related proteins, depletion of some neurotransmitters, abnormal electrophysiological activities of neurons, and declined anti-oxidative defenses, ultimately resulting in cerebral injuries (Hong et al. 2002; Geng et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2009). Therefore, it is necessary to develop effective strategies to fight against stress-induced neural injuries, so as to prevent stress-related disorders.

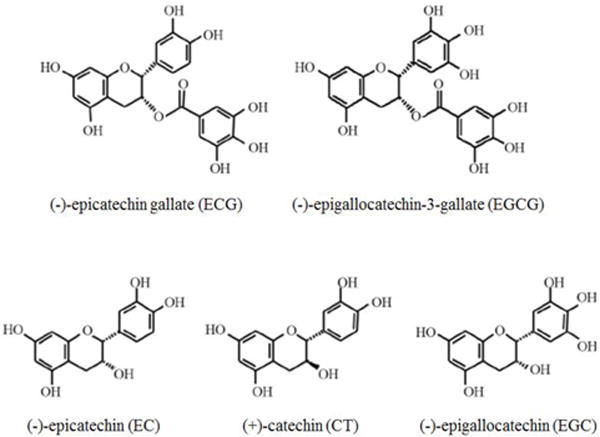

It has been shown that green tea polyphenols (GTPs), particularly its main active component, the epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), exhibited substantial neuro-protective/neuro-restorative effects against diverse cerebral injuries, including some neurodegenerative diseases (Weinreb et al. 2004; Guo et al. 2005; Baptista et al. 2014), cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury (Sutherland et al. 2005), and neural damages induced by toxic reagents (Levites et al. 2002; Levites et al. 2003; Mandel et al. 2004; Teixeira et al. 2013). Upon oral administration, GTPs can pass through the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (Abd El Mohsen et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2008; Solanki et al. 2015) to exert neuroprotective effects. Generally, green tea polyphenols (GTPs) contain five classes of chemicals, including EGCG and four catechin derivatives such as epicatechin gallate (ECG), epicatechin (EC), catechin (CT) and epigallocatechin (EGC) (Fig.1). Among them, EGCG is the most abundant and active content, accounting for ~30–50% of the total catechins (Yang et al. 2007). Therefore, EGCG has been extensively investigated as a potential therapeutic agent for preventing neurodegenerative diseases, cerebral trauma and other related pathogenesis. For instance, we previously demonstrated that GTPs and EGCG could attenuate psychological stress-induced cerebral impairments in rats (Chen et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2010), supporting the therapeutic potential of EGCG in protecting CNS against stress-induced dysfunctions.

Figure 1. The chemical structures of Green tea polyphenols (GTPs) (Goodman et al. 2013).

Based on the structural variations, GTPs are categorized into 5 derivatives, including epicatechin gallate (ECG), epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), epicatechin (EC), catechin (CT) and epigallocatechin (EGC).

At the present, the precise mechanism underlying EGCG-mediated neuroprotection remains unclear. In addition to its powerful antioxidant and radical scavenging properties (Weinreb et al. 2004; Mandel et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2014), EGCG also exhibits metal-chelating (Mandel et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2008), food-intake affecting (Chen et al. 2011), anti-apoptotic (Weinreb et al. 2004; Guo et al. 2005; Nie et al. 2002), mitochondrial-preserving (Sutherland et al. 2005), and signaling-modulating properties (Mandel et al. 2004; Menard et al. 2013; Shen et al. 2014). For instance, it is capable of regulating the neuritogenic/antineuritogenic action of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and Nogo-A (Gundimeda et al. 2014; Gundimeda et al. 2015), and modulating the expression of cell survival and death genes-regulating genes (Weinreb et al. 2003; Han et al. 2014). Various signal transducing pathways are critical for regulating many biological processes and cellular homeostasis, as disruption of these complex pathways is associated with various diseases. Although EGCG has been shown to confer protection against neurodegenerative diseases and tumorigenesis by modulating various signaling pathways (Mandel et al. 2004; Guo et al. 2006; Khan et al. 2006), its molecular targets involving in stress-related brain impairments remain unknown. Consistent with the critical roles of protein kinase C (PKC) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling pathways in the regulation of cell growth, motility, cell differentiation as well as cell survival, recent studies have shown that these stress-sensitive signaling pathways are closely associated with cognitive performances and mood processing (Qi et al. 2006; Sun and Alkon 2014). Therefore, the present study was conducted to explore the potential involvement of PKCα and ERK1/2 in EGCG-mediated protective effects against cerebral injuries induced by stress in Wistar rats.

Methods

Agents and chemicals

GTPs and EGCG (≥99% purity by high-performance liquid chromatography) were provided by Hangzhou Hetian Biotech Co., Ltd (Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China). Total Protein Extraction Kit and BCA Protein Assay Kit were purchased from Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Antibodies of PKCα, phospho-PKCα (pPKCα), ERK1/2, phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2), PGC-1α and β-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) blocking solution was purchased from Wuhan Boster Bio-engineering Co., Ltd (Wuhan, China). Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) Assay Kit was purchased from Millipore (USA). Cortisol Radioimmunoassay Kit was provided by Beifang Biotech Co., Ltd, (Beijing, China). Dopamine (DA) Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kit and serotonin (5-HT) Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kit were obtained from Shanghai Shiruike Biotech Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). ATP Assay Kit (ab83355) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Ultrapure RNA Kit was purchased from Beijing Kangwei Century Company (Beijing, China). All-in-one™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit was obtained from Guangzhou GeneCopoeia Co., Ltd, (Guangzhou, China). Other analytical grade chemicals and reagents were purchased from Beijing Chemical Reagent Company (Beijing, China).

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing 140–160 g were individually housed in cages with free access to fodder and water at the Animal Center of the Academy of Military Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). Room temperature of the animal facility was maintained at 23 ± 1°C. Animals were maintained on a 12:12-h light: dark cycle. After the rats were acclimated to laboratory conditions, we used the recently described 5-point Body Condition Scoring Technique to assess laboratory animal’s physical well-being, and excluded rats with bad scores from our study. The remaining 40 rats were randomly and evenly divided into four groups: normal control (CT), stress control (ST), and two stress groups supplemented with GTPs (GST) and EGCG (EST), respectively. GTPs and EGCG were dissolved in normal saline, and given to experimental animals by intragastric administration at a dose of 500 mg/kg·bw. ST group was given an equal volume of normal saline. The laboratory animals received humane care throughout the whole experiment according to the guidelines of the National Institute for Environmental Studies. All efforts were made to minimize both the number of animals used and their suffering.

Stress model

The laboratory animal model of psychological stress was developed by restraining the rats within the iron cylinder tube for four weeks as previously described (Thorsell et al. 2000). The restraint iron cylinder tubes were 8.5 inch in length and 2.0 inch in diameter, and covered on one end with a Plexiglas cover with small air holes (0.2 inch in diameter). These tubes fit closely to the body size of the animals, but restrained their free movement. Each rat in ST, GST and EST groups received repetitive restraint for six hours every day and lasted for a total of 28 days.

Spatial learning and memory testing

Open-field test

The open field is a 100 × 100 × 50 cm dark gray Plexiglas arena whose floor was divided by black lines into 25 equal squares. At the 29th day post the onset of the experiment, animals were gently and individually placed into the central square of the open field, facing the same designated wall in all of the tests. The testing room was dimly illuminated with indirect white lighting. They were allowed to explore the arena for 20 min on the first testing day, for 10 min on the next day, and for 5 min on the third day. During this time, the following variables were measured to assess exploration of the empty open field: latency (s), the number of squares crossed with the four paws, frequencies of rearing and modification (Walsh and Cummins 1976).

Step-through test

The step-through test was used to examine an animal’s light-dark passive avoidance response as previously described (Tanaka et al. 2006). The step-through apparatus consists of two chambers separated by a door that the animal can pass through. Prior to the test, a single acquisition (training) trial was performed, which consisted of a 30 s adaptation in one chamber that was dark at first, followed by the onset of a bright light. To avoid the light, the rat crossed over into the darkened adjacent chamber, but received a mild 0.8 mA foot-shock for 1s. The time to crossover from the light chamber to the darkened chamber (latency) was recorded with a maximum trial length of 300s. The animals were tested for recall 24 h after the acquisition period to ascertain whether they had been trained to criterion. The criterion of rat was remaining in the light chamber for 300s to avoid the foot-shock. Any animal that did not meet the criterion was retrained. The latency and frequency of foot-shocks were used to evaluate the ability of animals to remember adverse stimuli.

Determination of plasma levels of cortisol, dopamine and serotonin

Cortisol

The experimental rats were sacrificed by decapitation after being anesthetized with ether, and the whole blood samples were collected and immediately centrifuged for 15 min at 1,800 g to separate plasma from erythrocytes. The plasma was removed and stored at −80°C until used. Plasma cortisol concentration was measured using the Cortisol Radioimmunoassay Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, mix 20 μL of calibrators, controls and samples with 500 μL of 125I –cortisol, and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After removing the liquid and washing with 1 mL of distilled water, then emptying the tubes and taping firmly onto absorbent paper, leaving the tubes standing upside down for at least 5 min. Measure the remaining radioactivity bound to the tubes with a gamma scintillation counter calibrated for 125I. For each group of tubes compute the mean counts, draw up the calibration curve, and calculate sample values directly from the calibration curve.

Dopamine and serotonin

Plasma contents of dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT) were measured by DA and 5-HT Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. These assays employed the quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique with pre-coated specific monoclonal antibodies against DA and 5-HT respectively. Standards and samples were pipetted into the wells and any presenting DA or 5-HT is bound by the immobilized antibody. Enzyme-linked specific monoclonal antibodies to DA or 5-HT were added to the wells. Following a wash to remove any unbound antibody, a substrate solution was added to the wells and color develops in proportion to the amount of DA or 5-HT bound in the initial step. The color development was stopped and the intensity of the color was measured.

Western blotting

The samples of cortex (the Parietal Lobe, mainly the middle part of hemisphere) and hippocampus were quickly isolated after the animals were sacrificed, and snap-frozen for tissue homogenization. Samples were grinded with a RIPA buffer according to the specification sheet of Total Protein Extraction Kit. Then samples were ultrasonicated and centrifuged at 15,000g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was assayed for total protein concentration using BCA Protein Assay Kit. An equal amount of protein (50 μg) was loaded in each lane of a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. The proteins in each sample were electrophoretically separated, followed by a protein transfer to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was then incubated with tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 5% BSA and 0.05% Tween-20 for 2 h at room temperature to block nonspecific binding. For detection of designated proteins, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies in TBST containing 5% BSA overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies and concentrations were PKCα (1:1000); pPKCα (1:1000); ERK1/2(1:1000); pERK1/2(1:1000); PGC-1α (1:1500) and β-Actin (1:1000) antibodies. β-actin was used as an internal loading control. Membranes were washed with TBST 5 times, and then probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000 dilutions in TBST) for 1 h at room temperature with gentle shaking. Membranes were washed with TBST, and the immuno-reactivity was detected with the Enhanced Chemiluminiscence (ECL) Western Blot Detection system (WEST-ZOL®plus) and visualized with “ChemiDoc XRS’’ digital imaging system. Then protein expression was quantitated densitometrically with ‘MultiAnalist’ software from Bio-Rad laboratories Inc.

Detection of ATP contents in the hippocampus and cortex

The tissue samples of hippocampus and cortex were homogenized and ultrasonicated for 1.5 min, and centrifuged at 15,000g at 4°C for 10min. The supernatant was assayed for ATP productions by using an ATP Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the hippocampus and cortex using the Ultrapure RNA Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and its purity was confirmed by the A260/A280 ratio. Then the mRNA reversely transcribed into the first-strand cDNA using All-in-one™ First Strand cDNA synthesis Kit. Following reverse transcription, All-in-one qPCR Primer (2μM) and primers for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (Gapdh; Qiagen, QT01658692) were used to quantify the mRNA expression levels of respective genes using an ABI 7300HT Real-time PCR system (Applied Bio-systems, Foster City, CA, USA). Amplification was performed using the RT2 SYBR Green ROX qPCR Mastermix under the following conditions: 95°C 10m; followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10s, 60°C for 20s and 72°C for 15s. Immediately following the amplification step, a single cycle of the dissociation (melting) curve program was run at 95°C for 15s, at 60°C for 20s, then at 95°C for 15s, and last at 60°C for 15s. This cycle was followed by a melting curve analysis; baseline and cycle threshold values (Ct values) were automatically determined using the ABI 7300HT software. The relative mRNA expressions were calculated using the following formula: ΔΔC expression =2−ΔΔCt, where ΔΔCt = ΔCt (modulated group) − ΔCt (control group), ΔCt = Ct (target gene) − Ct (GAPDH) and Ct = cycle at which the threshold was reached. The relative abundance of mRNA expression in normal control group was set as an arbitrary unit of 1, and the gene expression in modulated groups was presented as folds of controls after normalization to GAPDH.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 10.0 software, and the results were expressed as mean ± SD (standard deviation). Experimental data were checked for Gaussian distribution. Two-tailed unpaired Student t tests were applied for comparison of two normally distributed groups; comparisons between more than two normally distributed groups were made by one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise multiple comparison (Student-Newman-Keuls method, q-test). The Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to examine the correlations between behavioral performances and plasma levels of cortisol, DA as well as 5-HT. Differences with P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Changes of animal behavioral performances in open-field test and step-through test

After prolonged (4 weeks) restraint stress, the rats exhibited significant impairment of brain functions as revealed by the open-field and step-through tests. As compared with the control (CT) group, the latency and frequencies of crossing, rearing and modification were significantly changed in the stressed (ST) group (t19=4.76, P<0.01; t19=4.18, P<0.01; t19=2.23, P<0.05; t19=2.12, P<0.05, respectively, Table 1). This stress-induced behavioral impairment was significantly attenuated in the GTP-treatment (GST) and EGCG-treatment (EST) groups (F3, 39=3.72, P<0.05; F3, 39=3.58, P<0.05, respectively, Table 1). The frequencies of crossing, rearing and modification of GST and EST group were also significantly increased to almost normal control level. Overall, the behavioral performance of rats in the EST group was better than that of GST group in the open field test.

Table 1.

Behavioral performances of rats in open-field test ( ± s)

| Group | n | Latency (s) |

Crossing (frequency) |

Rearing (frequency) |

Modification (frequency) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | 10 | 5.5±1.9 | 121.3±19.1 | 31.9±7.0 | 4.6±1.3 |

| ST | 10 | 19.4±4.7a | 80.0±20.3a | 23.6±7.9b | 2.8±0.7b |

| GST | 10 | 10.4±3.7bc | 115.3±30.7c | 31.0±7.2 c | 4.2±1.5c |

| EST | 10 | 9.1±3.6bc | 115.9±27.5c | 31.8±6.9 c | 4.0±0.8c |

The male Wistar rats weighing 140–160 g were randomly assigned into 4 groups (10 animals per group): normal control (CT), stress control (ST), stress and GTPs-modulation (GST), as well as stress and EGCG-modulation (EST) groups. Stress rats received restraint for 4 weeks; GTPs and EGCG were given to animals by intragastric administration once a day and lasted for 4 weeks. Then, open-field test was taken to examine animals’ behavioral performances. The results were showed as mean ± SD.

P<0.01,

P<0.05 vs CT group;

P<0.05 vs ST group

The step-through test demonstrated a similar change of the latency and shock frequency in various treatment groups (F3, 39=3.61, P<0.05; F3, 39=3.57, P<0.05, respectively, Table 2), confirming that GTPs and EGCG conferred significant protection against stress-induced brain impairment.

Table 2.

Behavioral performances of rats in step-through test ( ± s)

| Group | n | Latency (s) | Shock(frequency) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CT | 10 | 247.8±49.0 | 1.0±0.0 |

| ST | 10 | 86.7±13.3a | 2.1±0.8b |

| GST | 10 | 224.6±45.1c | 1.4±0.3d |

| EST | 10 | 225.8±39.7c | 1.1±0.5d |

The male Wistar rats weighing 140–160g were randomly assigned into 4 groups (10 animals per group), and subjected to stress and various treatment as described in the Legend of Table 1. At the end of the experiment, the step-through test was employed to examine animals’ behavioral performances, and the results were showed as mean ± SD.

P<0.01,

P<0.05 vs CT group;

P<0.01,

P<0.05 vs ST group

Changes of plasma levels of cortisol, dopamine and serotonin

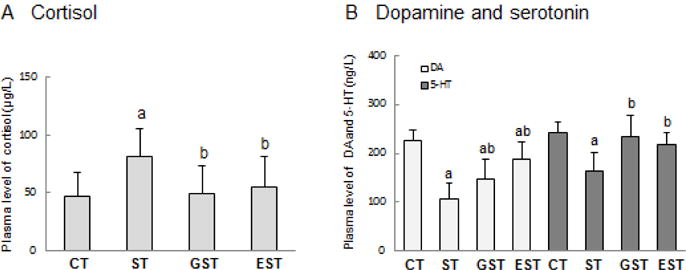

Glucocorticoid (GC) is an essential stress hormone and occupies an important role in stress-induced pathological impairment (Angelucci 2000; Bratt et al. 2001). The GC contents can signal the body’s stress intensity (Herman and Cullinan 1997). As predicted, the plasma cortisol levels were increased dramatically in the stressed rats (Fig.2A), but were significantly attenuated in GST and EST groups in contrast to that of ST group (t19=2.65, P<0.05; t19=2.43, P<0.05, respectively).

Figure 2. The levels of plasma cortisol, dopamine and serotonin.

Wistar rats weighing 140–160g were randomly assigned into 4 groups (10 animals per group): normal control (CT), stress control (ST), stress and GTPs-modulation (GST), as well as stress and EGCG-modulation (EST) groups. Stress rats received restraint for 4 weeks; GTPs and EGCG were given to animals by intragastric administration once a day and for 4 weeks. The whole blood samples were collected immediately after the rats were sacrificed, and were centrifuged to separate plasma. The contents of cortisol, dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT) were measured, and expressed as mean ± SD. a P<0.05 vs CT group;b P<0.05 vs ST group

Compared with CT group, plasma levels of DA were markedly declined in all the three stress groups (F3, 39=3.17, P<0.05, Fig.2B). Nevertheless, the plasma contents of DA were elevated in stressed animals that received GST and EST (t 19=2.51, P<0.05; t19=2.72, P<0.05, respectively). Similarly, the plasma level of 5-HT was also noticeably decreased in the ST group (t19=2.35, P<0.05, Fig.2B), but partially restored to almost control levels in the GST and EST groups (t19=2.69, P <0.05; t19=2.48, P<0.05, respectively).

The correlations between animal behavioral performance and plasma cortisol, dopamine and serotonin levels

We performed the correlational analysis between animal behavioral performance and their plasma levels of cortisol, dopamine and serotonin. The results suggested that the latency in open-field test had significant positive correlation with cortisol level, whereas had negative correlations with plasma contents of dopamine and serotonin (P<0.01, P<0.05, Table 3). Furthermore, the frequencies of animal crossing and rearing had prominent negative correlations with plasma cortisol, while had positive correlations with plasma dopamine and serotonin levels (Table 3).

Table 3.

The correlations between animal behavioral performance in open-field test and plasma levels of cortisol, dopamine and serotonin (Pearson correlation coefficient, r)

| Index | Latency | Crossing frequency | Rearing frequency | Modification frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | 0.992a | −0.973b | −0.968b | −0.945 |

| Dopamine | −0.915 | 0.859 | 0.842 | 0.722 |

| Serotonin | −0.953b | 0.990a | 0.992a | 0.895 |

P<0.01

P<0.05

In the step-through test, the latency had apparently negative correlation with plasma cortisol and positive correlations with serotonin content (P<0.05, Table 4). In addition, the shock frequency had remarkable positive correlation with cortisol level, while had negative correlation with serotonin levels (Table 4).

Table 4.

The correlations between animal behavioral performance in step-through test and plasma levels of cortisol, dopamine and serotonin (Pearson correlation coefficient, r)

| Index | Latency | Shock frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | −0.976a | 0.988a |

| Dopamine | 0.857 | −0.781 |

| Serotonin | 0.993b | −0.990b |

P<0.05;

P<0.01

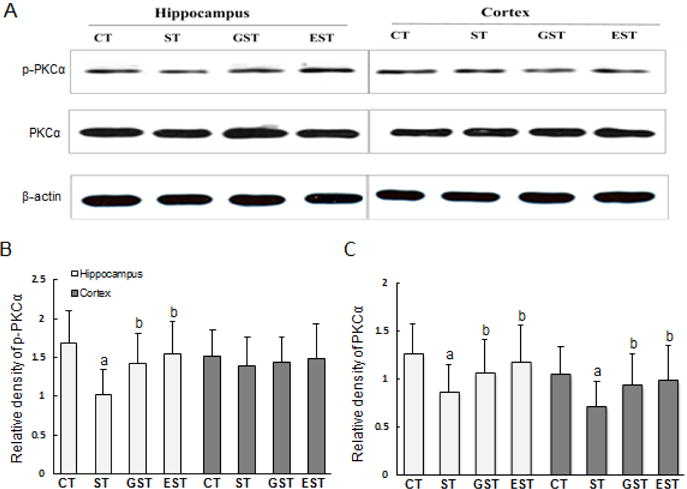

Changes in the expression and phosphorylation of PKCα, ERK1/2 in the hippocampus and cortex of rats

To understand the mechanisms underlying EGCG-mediated protection, we examined the active status of several key signaling molecules in the hippocampus and cortex. Both p-PKCα and PKCα contents in the hippocampus of stressed rats were declined markedly in comparison with that of CT group (Fig.3). This stress-induced decrease of PKCα and its phosphorylation was significantly attenuated in the GST and EST groups (Fig. 3B). In a sharp contrast, there was no significant difference of p-PKCα levels in the cortex between any of the four groups (Fig.3B). However, the expression of PKCα in the cortex showed notable difference, and had the similar changes with that in the hippocampus (Fig.3C).

Figure 3. Expression and phosphorylation of PKCα in the hippocampus and cortex of rats.

The hippocampus and cortex samples were quickly harvested after the animals were sacrificed, and snap-frozen for tissue homogenization. Proteins (50–100 μg) from tissue lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and blotted with specific antibodies against PKC α or p-PKC α. The specific signals were visualized with “ChemiDoc XRS’’ digital imaging system, and a representative Western blot was shown. β-actin was used as an internal control(A). The relative protein levels were expressed as the relative band density of the corresponding protein (B, C). a P<0.05 vs CT group;b P<0.05 vs ST group

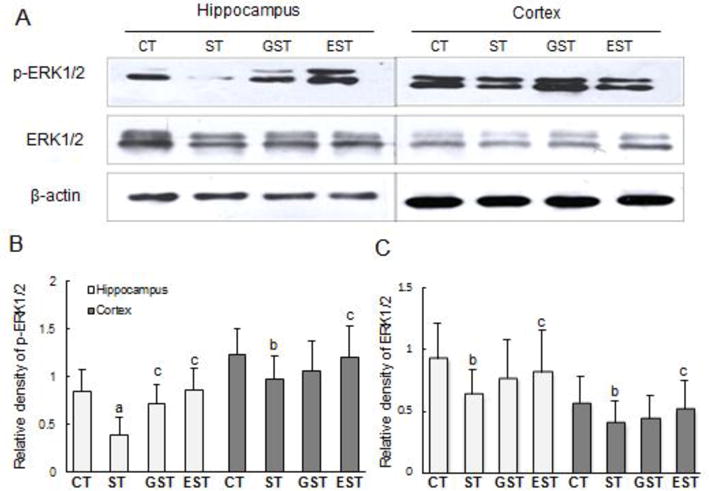

Similarly, the levels of p-ERK1/2 were significantly reduced both in the hippocampus and cortex of ST rats (Fig.4A, 4B). However, this stress-induced decrease of ERK1/2 phosphorylation was significantly attenuated in the hippocampus and cortex of GST and EST groups (Fig.4B). Interestingly, the contents of total ERK1/2 in the hippocampus and cortex showed similar changes with p-ERK1/2 (Fig.4C), suggesting that the stress-induced down-regulation of ERK1/2 might be attenuated by EGCG and GTPs treatments.

Figure 4. Expressions of ERK1/2 and phosphorylated ERK1/2 in the hippocampus and cortex of rats.

Proteins (50–100 μg) of the hippocampus and cortex tissue lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and blotted with specific antibodies against ERK1/2 or p-ERK1/2. The specific signals were visualized with “ChemiDoc XRS’’ digital imaging system, and a representative Western blot was shown. β-actin was used as an internal control(A). The relative protein levels were expressed as the relative band density of the corresponding protein (B, C). a P<0.01, b P<0.05 vs CT group;c P<0.05 vs ST group

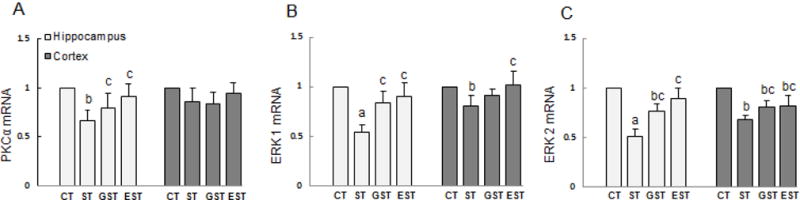

The expression of PKCα and ERK1/2 mRNA in the hippocampus and cortex of rats

To test this possibility, we measured the mRNA expression levels of the PKCα and ERK1/2 by real-time RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 5, the levels of PKCα and ERK1/2 mRNA were reduced in the hippocampus of ST group as compared with that of the CT group (Fig.5). In the cortex, only the expression levels of ERK1/2 mRNA, but not the PKCα, were significantly reduced (Fig.5B, 5C). The stress-induced alterations of PKCα and ERK1/2 in the hippocampus or cortex were significantly attenuated in both GST and EST groups (F3, 39=3.28, P<0.05; F3, 39=3.71, respectively, Fig.5).

Figure 5. The expressions of PKCα mRNA and ERK1/2 mRNA in the hippocampus and cortex of rats.

The samples of the hippocampus and cortex were quickly isolated after the animals were sacrificed, and snap-frozen for tissue homogenization. Total RNA was isolated, and the expression levels of PKCα and ERK1/2 mRNA were determined by real-time RT-PCR, and expressed as mean ± SD of Gapdh mRNA levels. a P<0.01, b P<0.05 vs CT group;c P<0.05 vs ST group.

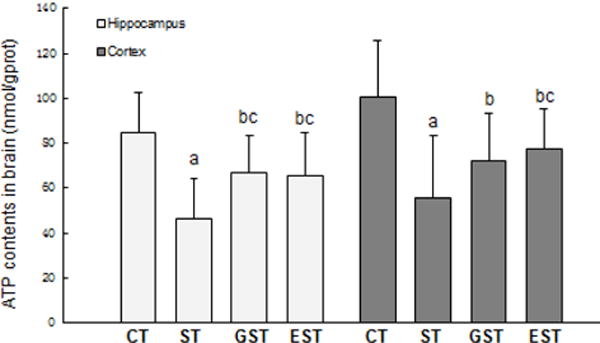

The changes of ATP production, PGC-1αand its mRNA expressions in the hippocampus and cortex of rats

As a measure of the CNS cellular function, the brain level of ATP after stress-induced injury was also assessed in parallel. As shown in Fig. 6, the ATP contents in the hippocampus and cortex tissues were significantly reduced in the ST rats (F3, 39=5.16, P<0.01, Fig.6). However, this stress-induced ATP reduction was significantly attenuated in the GST and EST groups (Fig.6).

Figure 6. The productions of ATP in the brain of rats.

The samples of the hippocampus and cortex were quickly isolated after the animals were sacrificed, and snap-frozen for tissue homogenization. The tissue levels of ATP was measured, and expressed as mean ± SD. a P<0.01, b P<0.05 vs CT group;c P<0.05 vs ST group.

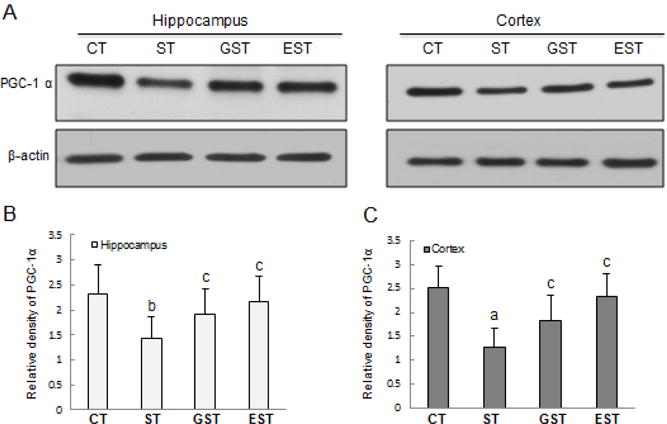

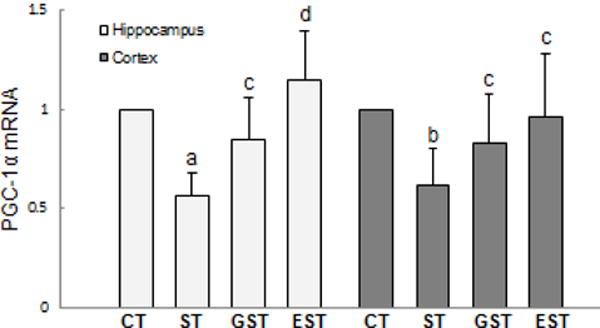

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) plays an important role in the regulation of cellular energy metabolism. Compared with normal control group, prolonged stress resulted in a significant decrease of PGC-1α production in both the hippocampus and cortex (Fig.7), which was attenuated in the GST and EST groups. Consistently, prolonged restraint stress also caused a significant reduction in the PGC-1α mRNA expression in both the hippocampus and cortex (Fig.8), which was similarly attenuated by the treatment with EGCG and GTPs (t19=2.28, P<0.05; t19=2.75, Fig.8).

Figure 7. The expression of PGC-1α in the hippocampus and cortex of rats.

The hippocampus and cortex samples were quickly harvested after the animals were sacrificed, and snap-frozen for tissue homogenization. Proteins (50–100 μg) from tissue lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and blotted with specific antibody against PGC-1 α, and the specific signals were visualized with “ChemiDoc XRS’’ digital imaging system. β-actin was used as an internal control. A representative Western blot result was shown (A). The quantitation of protein bands is expressed as relative density of the corresponding protein (B, C). a P<0.01, b P<0.05 vs CT group;c P<0.05 vs ST group.

Figure 8. The expression of PGC-1α mRNA in the hippocampus and cortex of rats.

The hippocampus and cortex samples were quickly isolated after the animals were sacrificed, and snap-frozen for tissue homogenization. Total RNA was isolated, the expression of PGC-1α mRNA was determined by real-time RT-PCR, and expressed as mean ± SD of Gapdh mRNA levels. a P<0.01, b P<0.05 vs CT group;c P<0.05, d P<0.01 vs ST group.

Discussion

As a neuro-protective agent, EGCG can modulate various intracellular signaling pathways to alter the expression of genes involving in the regulation of cell survival and apoptosis, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis (Weinreb et al. 2003; Mandel et al. 2004; Menard et al. 2013; Chang et al. 2014; Shen et al. 2014). In comparison with its conventional actions (e.g., anti-oxidation, metal-chelation and anti-apoptosis), its capacity in modulating cellular signal transducing pathways may bear some superiorities in treating neurodegenerative and other diseases (Mandel et al. 2004; Guo et al. 2006; Khan et al. 2006; Menard et al. 2013). We recently reported that EGCG could protect against neural injuries induced by psychological stress (Chen et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2010). In the present study, we sought to elucidate the protective mechanisms by examining the impact of EGCG and GTPs on the phosphorylation and expression of several key signaling molecules. Here we provided evidence that green tea polyphenolic catechins confer protection against stress-induced neural injury partly by restoring the PKC α and ERK1/2 signal pathways in the cerebrum, as well as recovering PGC-1α-mediated energy metabolism and ATP production.

Modern life is accompanied by increasing psychological stresses that may precipitate the onset of various diseases that demand for more effective therapies. The activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis has been known as a major component of host responses to stress (Adams et al. 2003). Psychological stress activates HPA, which results in the augmented production of glucocorticoids (GCs), and may contribute to the pathogenesis of stress-induced disorders (Angelucci 2000; Brattl et al. 2001). As an essential stress hormone and a measure of stress intensity (Herman and Cullinan 1997), the level of cortisol was found to be obviously increased in animals following prolonged (4 weeks) restraint stress, validating our successful establishment of the animal model of stress for the present study. The stress-induced impairment of brain functions was further verified by the open-field and step-through tests, as well as by the measurement of neurotransmitters (DA and 5-HT). DA is closely related with the modulation of cognitive behavior, awareness, attention as well as emotional state (Hao et al. 2001); and central serotonin (5-HT) dysregulation has great potential to increase the susceptibility to mental disorders, such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as learning and memory deficits (Eagle et al. 2009; Bari et al. 2009). In the present study, we found that EGCG as well as GTPs significantly attenuated this stress-induced behavioral impairment and alterations of blood levels of cortisol, dopamine and serotonin. Our correlational analysis indicated a positive correlation between the stress-induced behavioral disturbances and the levels of GC, DA and 5-HT, suggesting that the protective effects of EGCG and GTPs might relate to their up-regulation on DA and 5-HT levels.

During the last decade, significant advances have been achieved in understanding the neuroprotective effects that EGCG offers in preclinical setting. These neuroprotective actions are dependent on EGCG’s capability to cross the blood brain barrier. In vivo, oral administration of green tea polyphenols (35 mg/kg/day) led to their accumulation in the brain tissue (Abd EI et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2008), thereby preventing oxidative damage and memory regression and delaying senescence (Unno et al. 2007). In vitro, brain endothelial cell lines co-cultured with astrocytes can efficiently uptake many flavonoids (Solanki et al. 2015), suggesting that EGCG is capable of destinating to brain to exert its neuroprotection. Notably, the presence of multihydroxy groups and electron-rich aromatic rings in GTPs enables their extensive biotransformation, including methylation, sulfation, glucuronidation, and ring fission metabolism predominantly in the liver and intestine (Auger et al. 2008; Lambert and Yang 2003). Thus, the bioavailability of GTPs is relatively low after oral administration. For instance, the plasma contents were estimated by others around 1.2 μmol/L for EC after infusion at a dose of 50 mg/kg, 1.05 μmol/L for ECG if given at the same dose, and 12.3 μmol/L for EGCG after administration at 500 mg/kg (Feng 2006). Similarly, we found that oral administration of GTPs and EGCG at moderate levels (e.g., 500 mg/kg·bw) conferred protection against psychological stress-induced cognitive impairment and neural injuries (Chen et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2010). Nevertheless, other alternative strategies that could enhance the bioavailability, stability and efficiency of EGCG, such as various encapsulation techniques, acetylation modification, may facilitate EGCG’s beneficial activities in vivo (Hong et al. 2014; Zhu et al. 2014; Krupkova et al. 2016).

Accumulating evidence has suggested EGCG’s capacity in modulating various cellular signal transducing pathways to confer protective effects. For instance, EGCG can modulate the activation of signaling pathways of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), protein kinase C, nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), and ROS-NO (Reznichenko et al. 2006; Vasilevko et al. 2006; Guo et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2009; Sarkar et al. 2009; Gao et al. 2013; Song et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2015; Lin et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2016). Here we demonstrated that EGCG and GTPs treatment could restore PKC and ERK1/2 activation by enhancing their expression and phosphorylation in the hippocampus. As the prominent part of limbic system in the CNS, hippocampus is not only the neural center to regulate cognitive behaviors, but also the main cerebral domain to mediate stress response, as well as the primary target affected by the release of stress hormones (Kondoh et al. 2001). Therefore, the effective restoration of key cell signaling pathways by EGCG in the hippocampus may underlie a novel and powerful therapy against stress-induced brain injuries.

PKC is a family of serine/threonine kinases that can be categorized into three subclasses based on their activators: conventional (α, βI, βII,γ), novel (δ, ε, θ, η, μ) and atypical (ι, λ, ξ). PKC plays a critical role in the modulation of cell survival, programmed cell death, long-term-potentiation as well as in the amalgamation of various memories (Durkin et al. 1997; Vianna et al. 2000; de Barry et al. 2010). The rapid loss of neuronal PKC activity is a common consequence of some cerebrum injuries, such as dementias and glucose deprivation (Murai et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2012). Furthermore, increased PKC expression could potentially improve cognition, learning and memory along with anti-dementia action (Sun and Alkon 2014), which in turn would restore the normal PKC signaling. Increasing evidence supports the view that the restoration of PKC survival pathway underlies the neuro-protective action of Green-tea catechins against neurodegeneration and neural injuries induced by neurotoxins (such as Aβ, MPTP, and 6-OHDA). Specifically, EGCG has been demonstrated to cause a rapid activation of various PKC (particularly the α and ε) isoforms in the cerebrum and neuronal culture (Levites et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2004; Mandel et al. 2004; Reznichenko et al. 2005). Moreover, a general PKC inhibitor, GF109203X could completely abolish the EGCG-mediated protection, whereas a direct activator of PKC, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) mimicked the protective effect afforded by EGCG (Levitesl et al. 2002). In AD, amyloid beta fibrillation was inhibited by EGCG via modulating the PKC signaling pathway (Reznichenko et al. 2006; Vasilevko et al. 2006). In the present study, we found that EGCG enhanced PKCα activities in the hippocampus and cortex of stressed animals, suggesting that PKC signaling pathway might be involved in EGCG-mediated protection against stress-induced brain impairment.

In addition to PKC, the MAPK signaling pathways has also been implicated in the protective effects of EGCG. MAPKs are important members of the signaling cascades involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, inflammation, cytokines and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression (Hommes et al. 2003). They can be classified into 3 classes, namely ERK1/2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (c-JUK) and p38 (Johnson and Lapadat 2002). It has been established that ERK1/2 could act as a determinant for cell growth, cell differentiation, cell survival, motility and pro-survival signaling (Vauzour et al. 2007). Furthermore, it has been shown that ERK1/2 is highly sensitive to stress and closely related with cognitive performances and mood processing. The decrease of ERK levels in both the rats exposed to chronic forced-swim stress (Dwivedi et al. 2001) and the post-mortem brains of depressed suicide human subjects have been documented, and the decrease is correlated with depression-like behaviors (Qi et al. 2006). EGCG was shown to inhibit endoplasmic reticulum stress and improve the neurological status in a rat model of stroke by activating ERK pathway, and inducing the phosphorylation of the downstream substrate, cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB) (Yao et al. 2014). The increased CREB phosphorylation and BDNF expression in the hippocampus after long-term treatment of green tea catechins were associated with an improvement in animals learning tasks and memory deficits (Li et al. 2009b; Li et al. 2009c). Although EGCG and other flavonoids can activate MAPK signaling cascades in both neuronal (Schroeter et al. 2001; Levites et al. 2002) and non-neuronal cells (Chen et al. 2000; Gao et al. 2013), the reported effects of EGCG on MAPK pathway are still controversial (Sarkar et al. 2009; Gao et al. 2016). Here we showed that EGCG treatment could restore the expression and phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in the hippocampus and cortex of stressed animals. Notably, others have reported that EGCG conferred protection against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity by inhibiting ERK and NF-κB pathways in mice (Lee et al. 2009). Such discrepancies may be attributable to the use of different animal models, as well as the time points being compared (Li et al. 2009a).

With a higher energy demand, the cerebrum is extremely susceptible to mitochondrial dysfunction and ATP shortage. We found that the ATP contents and level of a key regulator of cellular energy metabolism, PGC-1α, in the brain were markedly declined in stressed animals, which were significantly attenuated by EGCG as well as GTPs treatments. PGC-1α is a transcriptional coactivator that regulates the expression of transcriptional factors involved in lipid and energy metabolism, inflammation, mitochondrial enzymes and redox homeostasis (Puigserver and Spiegelman 2003; Handschin and Spiegelman 2006). It is commonly expressed in tissues with a high-energy demand, such as brown adipose tissue, skeletal muscle and the cerebrum (Pinho et al. 2013; Lai et al. 2014). Studies of cellular and rodent models have provided compelling evidences that reduced transcription and/or protein expression of PGC-1 α in the brain is sufficient to recapitulate the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disease (Cui et al. 2006; St-Pierre et al. 2006); while neuronal overexpression of PGC-1α has been shown to protect neurons in vitro and in rodent models of Huntington’s disease (HD) (Cui et al. 2006), PD (St-Pierre et al. 2006; Zheng et al. 2010), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Da Cruz et al. 2012). Furthermore, PGC-1α expression is also decreased in patients of both AD and PD (Qin et al. 2009; Zheng et al. 2010; Katsouri et al. 2011). Therefore, PGC-1α appears to represent a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of metabolic or degenerative diseases, prompting investigators to search for potential therapeutic strategies that efficiently and specifically increase PGC-1α expression or its transcriptional activity. A recent study suggested that EGCG could up-regulate PGC-1α mRNA expression in HepG2 cells and differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Lee et al. 2016). In addition, EGCG was shown to suppress 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine (MPP)-induced oxidative stress via silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog (SIRT1)/PGC-1α signaling pathway and to increase PGC-1α mRNA level in PC12 cells (Ye et al. 2012). EGCG may promote mitochondrial biogenesis by increasing SIRT1-dependent PGC-1α deacetylation in cells derived from patients with Down’s syndrome (Valenti et al. 2013). These reports are in agreement with our findings that EGCG enhanced the PGC-1 α expression in the brain of stress animals.

Taken together, to the best of our knowledge, this study provides a novel neuro-protective mechanism of EGCG against stress-induced neural injuries by restoring PKCα and ERK1/2 signaling pathways, as well as the expression of key energy-regulating factor PGC-1α and ATP production. Future studies are warranted to further understand the pharmacological mechanisms underlying the EGCG-mediated modulation of the networks of cell signaling transduction and energy metabolism in the CNS, so as to lay a solid foundation to realize EGCG’s potential as a therapy in diverse neural injuries.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 81372987 and No. 81072294 to W.C.). H.W. was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS, R01GM063075) and the National Center of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM, R01AT05076).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- CNS

central nervous system

- DA

dopamine

- EGCG

epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2

- GC

glucocorticoids

- GTPs

green tea polyphenols

- HPA

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine or serotonin

- MPTP

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- pERK1/2

phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2

- PGC-1α

peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α

- PKC α

protein kinase C α

- pPKC α

phosphorylated protein kinase C α

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

W Chen and X Zhao designed the study, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript; X Zhao, F Liu, H Jin, R Li, and Y Wang performed the experiments; W Zhang, and H Wang edited and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Abd El Mohsen MM, Kuhnle G, Rechner AR, Schroeter H, Rose S, Jenner P, Rice-Evans CA. Uptake and metabolism of epicatechin and its access to the brain after oral ingestion. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1693–1702. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams F, Grassie M, Shahid M, Hill DR, Henry B. Acute oral dexamethasone administration reduces levels of orphan GPCR glucocorticoid-induced receptor (GIR) mRNA in rodent brain: potential role in HPA-axis function. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;117:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00280-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelucci L. The glucocorticoid hormone: from pedestal to dust and back. Eur J Pharmcol. 2000;405:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger C, Mullen W, Hara Y, Crozier A. Bioavailability of polyphenon E flavan-3-ols in humans with an ileostomy. J Nutr. 2008;138:1535S–1542S. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.8.1535S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista FI, Henriques AG, Silva AM, Wiltfang J, da Cruze Silva OA. Flavonoids as therapeutic compounds targeting key proteins involved in Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5:83–92. doi: 10.1021/cn400213r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari A, Eagle DM, Mar AC, Robinson ESJ, Robbins TW. Dissociable effects of noradrenaline, dopamine, and serotonin uptake blockade on stop task performance in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2009;205:273–283. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1537-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratt AM, Kelly SP, Knowles JP, Barrett J, Davis K, Davis M, Mittleman G. Long term modulation of the HPA axis by the hippocampus behavioral, biochemical and immunological endpoints in rats exposed to chronic mild stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26:121–145. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindley D, Rolland Y. Possible connections between stress, diabetes, obesity, hypertension and alters lipoprotein metabolism that may result in atherosclerosis. Clin Sci. 1989;77:453–461. doi: 10.1042/cs0770453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CW, Hsieh YH, Yang WE, Yang SF, Chen Y, Hu DN. Epigallocatechingallate inhibits migration of human uveal melanoma cells via downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity and ERK1/2 pathway. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:141582. doi: 10.1155/2014/141582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Yu R, Owuor ED, Kong AN. Activation of antioxidant-response element (ARE), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and caspases by major green tea polyphenol components during cell survival and death. Arch Pharm Res. 2000;23:605–612. doi: 10.1007/BF02975249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WQ, Zhao XL, Hou Y, Li ST, Hong Y, Wang DL, Cheng YY. Protective effects of green tea polyphenols on cognitive impairments induced by psychological stress in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2009;202:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WQ, Cheng YY, Zhao XL, Li ST, Hou Y, Hong Y. Effects of zinc on the induction of metallothionein isoforms in hippocampus in stress rats. Exp Bio Med. 2006;231:1564–1568. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WQ, Zhao XL, Wang DL, Li ST, Hou Y, Hong Y, Cheng YY. Effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate on behavioral impairments induced by psychological stress in rats. Exp Bio Med. 2010;235:577–583. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.009329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YK, Cheung C, Reuhl KR, Liu AB, Lee MJ, Lu YP, Yang CS. Effects of green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate on newly developed high-fat/Western-style diet-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome in mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:11862–11871. doi: 10.1021/jf2029016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Barry J, Liégeois CM, Janoshazi A. Protein kinase C as a peripheral biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Jeong H, Borovecki F, Parkhurst CN, Tanese N, Krainc D. Transcriptional repression of PGC-1alpha by mutant huntingtin leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration. Cell. 2006;127:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Cruz S, Parone PA, Lopes VS, et al. Elevated PGC-1alpha activity sustains mitochondrial biogenesis and muscle function without extending survival in a mouse model of inherited ALS. Cell Metab. 2012;15:778–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin JP, Tremblay R, Chakravarthy B, Mealing G, Morley P, Small D, Song D. Evidence that the early loss of membrane protein kinase C is a necessary step in the excitatory amino acid-induced death of primary cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 1997;68:1400–1412. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68041400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y, Rizavi HS, Roberts RC, Conley RC, Tamminga CA, Pandey GN. Reduced activation and expression of ERK1/2 MAP kinase in the post-mortem brain of depressed suicide subjects. J Neurochem. 2001;77:916–928. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle DM, Lehmann O, Theobald DEH, Pena Y, Zakaria R, Ghosh R, Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Serotonin depletion impairs waiting but not stop-signal reaction time in rats: implications for theories of the role of 5-HT in behavioral inhibition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1311–1321. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng WY. Metabolism of green tea catechins: an overview. Curr Drug Metab. 2006;7:755–809. doi: 10.2174/138920006778520552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TB, Saab BJ, Mansuy IM. Neural mechanisms of stress resilience and vulnerability. Neuron. 2012;75:747–761. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Li W, Jia L, Li B, Chen YC, Tu Y. Enhancement of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate and theaflavin-3–3′-digallate induced apoptosis by ascorbic acid in human lung adenocarcinoma SPC-A-1 cells and esophageal carcinoma Eca-109 cells via MAPK pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;438:370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Rankin GO, Tu Y, Chen YC. Theaflavin-3, 3′-digallate decreases human ovarian carcinoma OVCAR-3 cell-induced angiogenesis via Akt and Notch-1 pathways, not via MAPK pathways. Int J Oncol. 2016;48:281–292. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng ZH, Cheng YY, Hong Y, Ma XL, Li ST, Wang DL. Study on the effects of stress on the calcium status of hippocampus neuron in rats with different zinc status and relevant mechanisms. Acta Nutr Sin. 2003;25:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman BA, Yeretzian C, Stolze K, Wen D. Quality aspects of coffees and teas: Application of electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy to the elucidation of free radical and other processes. Agr Sci. 2013;4:433–442. [Google Scholar]

- Gundimeda U, McNeill TH, Barseghian BA, Tzeng WS, Rayudu DV, Cadenas E, Gopalakrishna R. Polyphenols from green tea prevent antineuritogenic action of Nogo-A via 67-kDa laminin receptor and hydrogen peroxide. J Neurochem. 2015;132:70–84. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundimeda U, McNeill TH, Fan TK, Deng R, Rayudu D, Chen Z, Cadenas E, Gopalakrishna R. Green tea catechins potentiate the neuritogenic action of brain-derived neurotrophic factor: role of 67-kDa laminin receptor and hydrogen peroxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;445:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Bezard E, Zhao B. Protective effect of green tea polyphenols on the SH-SY5Y cells against 6-OHDA induced apoptosis through ROS-NO pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Lu J, Subramanian A, Sonenshein GE. Microarray-assisted pathway analysis identifies mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling as a mediator of resistance to the green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate in her-2/neu-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5322–5329. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Yan J, Yang T, Yang X, Bezard E, Zhao B. Protective effects of green tea polyphenols in the 6-OHDA rat model of Parkinson disease through inhibition of ROS-NO pathway. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1353–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Wang M, Jing X, Shi H, Ren M, Lou H. (−)-Epigallocatechin gallate protects against cerebral ischemia-induced oxidative stress via Nrf2/ARE signaling. Neurochem Res. 2014;39:1292–9. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 coactivators, energy homeostasis, and metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:728–735. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S, Avraham Y, Bonne O, Berry EM. Separation-induced body weight loss, impairment in alternation behavior, and autonomic tone: effects of tyrosine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;68:273–281. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Cullinan WE. Neurocircuitry of stress: central control of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommes DW, Peppelenbosch MP, van Deventer SJH. Mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase signal transduction pathways and novel anti-inflammatory targets. Gut. 2003;52:144–151. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Cheng YY, Ma Q, Wang DL, Li ST. The protection of vitamin E on LTP in hippocampal dentate gyrus of rats under stress. Chin J Appl Physiol. 2002;18:142–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Xu Y, Yin JF, Jin J, Jiang Y, Du Q. Improving the effectiveness of (−)- epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) against rabbit atherosclerosis by EGCG-loaded nanoparticles prepared from chitosan and polyaspartic acid. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:12603–12609. doi: 10.1021/jf504603n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 2002;298:1911–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsouri L, Parr C, Bogdanovic N, Willem M, Sastre M. PPARgamma co-activator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha) reduces amyloid-beta generation through a PPARgamma-dependent mechanism. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25:151–162. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N, Afaq F, Saleem M, Ahmad N, Mukhtar H. Targeting multiple signaling pathways by green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2500–2505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Ahn BH, Kim J, et al. Phospholipase C, protein kinase C, Ca/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, and redox state are involved in epigallocatechin gallate-induced phospholipase D activation in human astroglioma cells. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:3470–3480. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-2956.2004.04242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondoh M, Inoue Y, Atagi S, Futakawa N, Higashimoto M, Sato M. Specific induction of metallothionein synthesis by mitochondrial oxidative stress. Life Sci. 2001;69:2137–2146. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupkova O, Ferguson SJ, Wuertz-Kozak K. Stability of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate and its activity in liquid formulations and delivery systems. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;37:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L, Wang M, Martin OJ, Leone TC, Vega RB, Han X, Kelly DP. A role for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 (PGC-1) in the regulation of cardiac mitochondrial phospholipid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:2250–2259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.523654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JD, Yang CS. Cancer chemopreventive activity and bioavailability of tea and tea polyphenols. Mutat Res. 2003:523–524. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00336-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Lee YK, Ban JO, Ha TY, Yun YP, Han SB, Oh KW, Hong JT. Green tea (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits beta-amyloid-induced cognitive dysfunction through modification of secretase activity via inhibition of ERK and NF-kappa B pathways in mice. J Nutr. 2009;139:1987–1993. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.109785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Lee S, Doo M, Kim Y. Green tea (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate induces PGC-1 α gene expression in HepG2 cells and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2016;21:62–67. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2016.21.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levites Y, Amit T, Mandel S, Youdim MBH. Neuroprotection and neurorescue against amyloid beta toxicity and PKC-dependent release of non-amyloidogenic soluble precursor protein by green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. FASEB J. 2003;17:952–954. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0881fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levites Y, Amit T, Youdim MBH, Mandel S. Involvement of protein kinaseCactivation and cell survival/cell cycle genes in green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate neuroprotective action. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30574–30580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhang L, Huang Q. Differential expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in the hippocampus of rats exposed to chronic unpredictable stress. Behav Brain Res. 2009a;205:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhao HF, Zhang ZF, Liu ZG, Pei XR, Wang JB, Cai MY, Li Y. Long-term administration of green tea catechins prevents age-related spatial learning and memory decline in C57BL/6 J mice by regulating hippocampal cyclic amp-response element binding protein signaling cascade. Neuroscience. 2009b;159:1208–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhao HF, Zhang ZF, Liu ZG, Pei XR, Wang JB, Li Y. Long-term green tea catechin administration prevents spatial learning and memory impairment in senescence-accelerated mouse prone-8 mice by decreasing Abeta1–42 oligomers and upregulating synaptic plasticity-related proteins in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2009c;163:741–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Peng N, Li XP, Le WD. (−)-Epigallocatechin gallate regulates dopamine transporter internalization via protein kinase C-dependent pathway. Brain Res. 2006;1097:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CM, Chang H, Wang BW, Shyu KG. Suppressive effect of epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate on endoglin molecular regulation in myocardial fibrosis in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Mol Med. 2016;20:2045–2055. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda-Yamamoto M, Suzuki N, Sawai Y, Miyase T, Sano M, Hashimoto-Ohta A, Isemura M. Association of suppression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation by epigallocatechin gallate with the reduction of matrix metalloproteinase activities in human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:1858–1863. doi: 10.1021/jf021039l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel SA, Avramovich-Tirosh Y, Reznichenko L, Zheng H, Weinreb O, Amit T, Youdim MB. Multifunctional activities of green tea catechins in neuroprotection. Neurosignals. 2005;14:46–60. doi: 10.1159/000085385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel S, Maor G, Youdim MB. Iron and alphasynuclein in the substantia nigra of MPTP-treated mice: effect of neuroprotective drugs R-apomorphine and green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. J Mol Neurosci. 2004a;24:401–416. doi: 10.1385/JMN:24:3:401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel S, Weinreb O, Amit T, Youdim MBH. Cell signaling pathways in the neuroprotective actions of the green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem. 2004b;88:1555–1569. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard C, Bastianetto S, Quirion R. Neuroprotective effects of resveratrol and epigallocatechin gallate polyphenols are mediated by the activation of protein kinase C gamma. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:281. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murai Y, Okabe Y, Tanaka E. Activation of protein kinase A and C prevents recovery from persistent depolarization produced by oxygen and glucose deprivation in rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2012;107:2517–2525. doi: 10.1152/jn.00537.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie G, Jin C, Cao Y, Shen S, Zhao B. Distinct effects of tea catechins on 6-hydroxydopamine-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;397:84–90. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradovic J, Boyce WT. Individual differences in behavioral, physiological, and genetic sensitivities to contexts: implications for development and adaptation. Dev Neurosci. 2009;31:300–308. doi: 10.1159/000216541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike JL, Smith TL, Hauger RL, Nicassio PM, Patterson TL, McClintick J, Costlow C, Irwin MR. Chronic life stress alters sympathetic, neuroendocrine, and immune responsibility to an acute psychological stressor in humans. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:447–457. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199707000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinho RA, Pinho CA, Tromm CB, Pozzi BG, Souza DR, Silva LA, Tuon T, Souza CT. Changes in the cardiac oxidative metabolism induced by PGC-1{alpha}: response of different physical training protocols in infarction-induced rats. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:4560–4562. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigserver P, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1 alpha): transcriptional coactivator and metabolic regulator. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:78–90. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Lin W, Li J, Pan Y, Wang W. The depressive-like behaviors are correlated with decreased phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in rat brain following chronic forced swim stress. Behav Brain Res. 2006;175:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin W, Haroutunian V, Katsel P, Cardozo CP, Ho L, Buxbaum JD, Pasinetti GM. PGC-1alpha expression decreases in the Alzheimer disease brain as a function of dementia. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:352–361. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznichenko L, Amit T, Youdim MB, Mandel S. Green tea polyphenol (–)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate induces neurorescue of long-term serum-deprived PC12 cells and promotes neurite outgrowth. J Neurochem. 2005;93:1157–1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznichenko L, Amit T, Zheng H, Avramovich-Tirosh Y, Youdim MBH, Weinreb O, Mandel S. Reduction of iron-regulated amyloid precursor protein and β-amyloid peptide by (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate in cell cultures: Implications for iron chelation in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2006;97:527–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar FH, Li Y, Wang Z, Kong D. Cellular signaling perturbation by natural products. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1541–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter H, Spencer JP, Rice-Evans C, Williams RJ. Flavonoids protect neurons from oxidized low-densitylipoprotein-induced apoptosis involving c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), c-Jun and caspase-3. Biochem J. 2001;358:547–557. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Zhang Y, Feng Y, Zhang L, Li J, Xie YA, Luo X. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits cell growth, induces apoptosis and causes S phase arrest in hepatocellular carcinoma by suppressing the AKT pathway. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:791–796. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanki I, Parihar P, Mansuri ML, Parihar MS. Flavonoid-based therapies in the early management of neurodegenerative diseases. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:64–72. doi: 10.3945/an.114.007500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Huang YW, Tian Y, Wang XJ, Sheng J. Mechanism of action of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate: auto-oxidation-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 in Jurkat cells. Chin J Nat Med. 2014;12:654–662. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(14)60100-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre J, Drori S, Uldry M, et al. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006;127:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun MK, Alkon DL. Activation of protein kinase C isozymes for the treatment of dementias. Adv Pharmacol. 2012;64:273–302. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394816-8.00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun MK, Alkon DL. The “memory kinases”: Roles of PKC isoforms in signal processing and memory formation. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2014;122:31–59. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420170-5.00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland BA, Shaw OM, Clarkson AN, Jackson DM, Sammut IA, Appleton I. Neuroprotective effects of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate after hypoxia-ischemia-induced brain damage: novel mechanisms of action. FASEB J. 2005;19:258–260. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2806fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Ide M, Shibutani T, Ohtaki H, Numazawa S, Shioda S, Yoshida T. Lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation induces learning and memory deficits without neuronal cell death in rats. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:557–566. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira MD, Souza CM, Menezes AP, Carmo MR, Fonteles AA, Gurgel JP, Lima FA, Viana GS, Andrade GM. Catechin attenuates behavioral neurotoxicity induced by 6-OHDA in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;110:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsell A, Michalkiewicz M, Dumont Y, Quirion R, Caberlotto L, Rimondini R, Mathé AA, Heilig M. Behavioral insensitivity to restraint stress, absent fear suppression of behavior and impaired spatial learning in transgenic rats with hippocampal neuropeptide Y overexpression. PNAS. 2000;97:12852–12857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220232997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unno K, Takabayashi F, Yoshida H, Choba D, Fukutomi R, Kikunaga N, Kishido T, Oku N, Hoshino M. Daily consumption of green tea catechin delays memory regression in aged mice. Biogerontology. 2007;8:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s10522-006-9036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenti D, De Rasmo D, Signorile A, Rossi L, de Bari L, Scala I, Granese B, Papa S, Vacca RA. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents oxidative phosphorylation deficit and promotes mitochondrial biogenesis in human cells from subjects with Down’s syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:542–552. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilevko V, Cribbs DH. Novel approaches for immunotherapeutic intervention in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int. 2006;49:113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauzour D, Vafeiadou K, Rice-Evans C, Williams RJ, Spencer JPE. Activation of pro-survival Akt and ERK1/2 signalling pathways underlie the anti-apoptotic effects of flavanones in cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 2007;103:1355–1367. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vianna MRM, Barros DM, Silva T, Choi H, Madche C, Rodrigues C, Medina JH, Izquierdo I. Pharmacological demonstration of the differential involvement of protein kinase C isoforms in short- and long-term memory formation and retrieval of one-trial avoidance in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;150:77–84. doi: 10.1007/s002130000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh RN, Cummins RA. The open-field test: a critical review. Psychol Bull. 1976;83:482–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreb O, Mandel S, Amit T, Youdim MBH. Neurological mechanisms of green tea polyphenols in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson′s diseases. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:506–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreb O, Mandel S, Youdim MBH. Gene and protein expression profiles of anti- and pro-apoptotic actions of dopamine, R-apomorphine, green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, and melatonin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;993:351–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CS, Lambert JD, Ju J, Lu G, Sang S. Tea and cancer prevention: molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;224:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao C, Zhang J, Liu G, Chen F, Lin Y. Neuroprotection by (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate in a rat model of stroke is mediated through inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:69–76. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q, Ye L, Xu X, Huang B, Zhang X, Zhu Y, Chen X. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate suppresses1-methyl-4-phenylpyridine-induced oxidative stress in PC12 cells via the SIRT1/PGC-1α signaling pathway. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:82. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Yu H, Li X, Jin C, Zhao Y, Xu S, Sheng X. P38 MAPK/miR-1 are involved in the protective effect of EGCG in high glucose-induced Cx43 downregulation in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Cell Biol Int. 2016;40:934–942. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Rusciano D, Osborne NN. Orally administered epigallocatechin gallate attenuates retinal neuronal death in vivo and light-induced apoptosis in vitro. Brain Res. 2008;1198:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wu M, Lu F, Luo N, He ZP, Yang H. Involvement of α7 nAChR signaling cascade in epigallocatechin gallate suppression of β-amyloid-induced apoptotic cortical neuronal insults. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:66–77. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8491-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B, Liao Z, Locascio JJ, et al. PGC-1α, a potential therapeutic target for early intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:52ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao CG, Zhou P, Wu YB. Impact and significance of EGCG on Smad, ERK, and β-catenin pathways in transdifferentiation of renal tubular epithelial cells. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:2551–2560. doi: 10.4238/2015.March.30.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Li Y, Li Z, Ma CY, Lou ZX, Yokoyama W, Wang HX. Lipase-catalyzed synthesis of acetylated EGCG and antioxidant properties of the acetylated derivatives. Food Res Int. 2014;56:279–286. [Google Scholar]