Abstract

Urine samples are increasingly used for diagnosing infections including Escherichia coli, Ebola virus, and Zika virus. However, extraction and concentration of nucleic acid biomarkers from urine is necessary for many molecular detection strategies such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Since urine samples typically have large volumes with dilute biomarker concentrations making them prone to false negatives, another impediment for urine-based diagnostics is the establishment of appropriate controls particularly to rule out false negatives. In this study, a mouse glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) DNA target was added to retrospectively collected urine samples from tuberculosis (TB)-infected and TB-uninfected patients to indicate extraction of intact DNA and removal of PCR inhibitors from urine samples. We tested this design on surrogate urine samples, retrospective 1 milliliter (mL) urine samples from patients in Lima, Peru and retrospective 5 mL urine samples from patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Extraction/PCR control DNA was detectable in 97% of clinical samples with no statistically significant differences among groups. Despite the inclusion of this control, there was no difference in the amount of TB IS6110 Tr-DNA detected between TB-infected and TB-uninfected groups except for samples from known HIV-infected patients. We found a increase in TB IS6110 Tr-DNA between TB/HIV co-infected patients compared to TB-uninfected/HIV-infected patients (N=18, p=0.037). The inclusion of an extraction/PCR control DNA to indicate successful DNA extraction and removal of PCR inhibitors should be easily adaptable as a sample preparation control for other acellular sample types.

Introduction

Biomarkers for infectious diseases may be obtained from several types of patient samples including blood, sputum, stool, and urine. Many factors affect the sample choice, including characteristics of the infection, concentration of the biomarker, volume of sample available, biomarker stability within the sample, and patient willingness to provide the sample. Patient willingness to provide samples and the improved sensitivity of molecular reagents has led to the detection of biomarkers from urine samples being increasingly used for diagnosis of infectious diseases, including Escherichia coli [1], leptospirosis [2], Mycobacterium tuberculosis [3], Dengue virus [4], Zaire Ebola virus [5], and Zika virus [6]. Urine samples are particularly advantageous for diagnosing infectious diseases such as tuberculosis (TB), because sample collection is non-invasive, sample volumes are relatively large, and samples are more easily obtained from patients than blood or sputum samples [3]. However, even in the case of DNA excreted in urine, often referred to as trans-renal DNA (Tr-DNA), DNA biomarkers must still be extracted and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) inhibitors must be removed prior to analysis. Green and colleagues identified Tr-DNA extraction as a critical barrier to make TB diagnosis using urine a feasible option[3]. A number of factors contribute to the successful completion of the extraction step. First, most commercially available extraction kits require additional laboratory equipment and trained laboratory personnel, and second, most commercial DNA extraction kits can only accommodate small sample volumes, usually less than 1 milliliter (mL) and variability in the extraction method used affects diagnostic performance [7]. As pointed out by Green et al [3], since the presence of TB DNA biomarkers in urine remains controversial, new designs that include indicators of successful sample preparation are needed. Many other types of patient samples typically contain intact cells which serve as a reservoir for endogenous DNA controls. Unfortunately, urine samples contain few intact cells so that the use of endogenous controls from this source is unavailable [3]. We previously reported a relatively simple method to extract and concentrate nucleic acid biomarkers from larger volume patient samples using magnetic beads [8,9]. The use of magnetic bead nucleic acid extraction is advantageous because the processing is self-contained and relies on simple magnetically-induced movement of beads without the need for expensive laboratory equipment. In this report, we describe an approach to address the need for endogenous controls for urine samples based on modifications to our previous reported laboratory studies using surrogate urine samples to detect Tr-DNA sequences of Mycobacterium tuberculosis IS6110 [10–13], a sequence that has been reported to be repeated up to 25 times within the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome [3]. We describe an improvement to diagnostic design aimed at reducing false negatives due to failure in DNA extraction or PCR failure. To achieve this we add a 120 base pair segment of the mouse glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) DNA to the lyophilized reagents used in our previous method [8,9] that rehydrates in the patient sample. Detection of this DNA fragment is used to reduce false negatives in two ways: 1) to indicate that DNA was successfully extracted and 2) that PCR inhibitors have been reduced to a level that they no longer prevent DNA amplification. We report on the performance on this extraction/PCR control and on its application to classify retrospectively collected samples of urine from TB-infected and uninfected patients from Peru and South Africa.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of urine collection pipettes

The urine collection pipettes were prepared following the protocol of Bordelon et al. [8] with modification. For 1 mL urine samples, pipettes were prepared by drawing 1 mL of DNA-silica adsorption buffer (4 M guanidinium thiocyanate, 25 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0) containing 6 × 108 Dynabeads MyOne silane magnetic beads and 5 × 106 copies of a 120 bp segment of the Mus musculus GAPDH gene into the bulb of a 5 mL, fine tipped transfer pipette (Samco Scientific, catalog # 232-20S). For 5 mL urine samples, 5 mL of DNA-silica adsorption buffer containing 1.8 × 109 Dynabeads MyOne silane magnetic beads and 5 × 107 copies of the mouse GAPDH positive extraction control sequence was drawn into the bulb of a 15 mL, narrow stemmed transfer pipette (Fisher Scientific, catalog # 13-711-36). The contents of the transfer pipettes were frozen at −80°C for 2 hours, after which the pipettes were transferred to a Labconco bulk tray dryer and lyophilized for 36 hours. Following lyophilization, the transfer pipettes were stored at room temperature for 1–2 weeks prior to use.

Preparation of surrogate healthy control patient samples

Urine samples were received from Vanderbilt University Hospital from de-identified disease-free healthy control patients. Use of these samples was approved by Vanderbilt University institutional review board (IRB). Fifteen mL of each sample were pooled, pipetted into 1 mL aliquots, and stored at −80°C. Samples were pooled to eliminate patient variation during assay development. Immediately prior to use, the samples were thawed at room temperature.

A mouse GAPDH DNA PCR template was added to lyophilized DNA extraction reagents in order to serve as an extraction/PCR control to indicate the extraction of intact DNA and removal of PCR inhibitors. One mL urine samples were spiked with 5 × 108 copies of a 140 base pair (bp) DNA target within the IS6110 sequence of M. tuberculosis (synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), Coralville, IA, resuspended in TE buffer with further dilutions in H2O) [8]. In a 5 mL transfer pipette, urine samples were mixed for 30 seconds with 1 mL of DNA-silica adsorption buffer (4 molar [M] guanidinium thiocyanate, 25 millimolar [mM] sodium citrate, pH 7.0), 5 × 108 copies of a 120 bp segment of the Mus musculus GAPDH gene (GenBank Accession NM 008084, synthesized by IDT, Coralville, IA, resuspended in TE buffer with further dilutions in H2O) and 6 × 108 Dynabeads MyOne silane magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog # 37002D). TB IS6110 DNA and mouse GAPDH DNA were extracted from urine and amplified by PCR as described below.

Urine samples from Lima, Peru

One mL frozen urine samples were obtained from the University of Cayetano in Lima, Peru. Ethical approval was obtained from the Comité de ética de la Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia and the Comité de Etica del Hospital Nacional Cayetano Heredia. All 40 samples were from HIV-uninfected patients. Samples had been aliquotted and frozen upon collection and were not thawed until immediately prior to use. Twenty samples were from patients with culture-confirmed pulmonary TB, and 20 were from patients with symptomatic respiratory disease not due to pulmonary TB (i.e. culture negative). The culture negative control patients underwent a diagnostic and clinical evaluation to rule out TB disease. All 40 Peruvian samples were processed over four days in the Haselton laboratory at Vanderbilt University.

Urine samples from Cape Town, South Africa

Our previous study showed that keeping the concentration of DNA target the same and increasing the volume of urine from 1ml to 5ml increases the quantity of DNA target present in the small eluate volume [8]. Therefore, for our second set of retrospective samples we increased the sample volume from 1 to 5 ml. In addition, for these samples we also tested for DNase activity. Five mL frozen urine samples from 47 patients with culture-confirmed pulmonary TB and 39 patients with symptomatic respiratory disease not due to pulmonary TB were obtained from the Blackburn Lab at the University of Cape Town in Cape Town, South Africa. Ethical approval was obtained from University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 007/2012). A detailed storage history of the samples was not available, but each had been frozen and thawed an estimated 5 times. All 86 South African samples were processed over 5 days in the Blackburn laboratory at the University of Cape Town.

Extraction and concentration of DNA from urine samples

To process each sample, a 10 cm length of 0.93 mm inner diameter FEP tubing was preloaded with DNA eluent (50 microliters [ul] nuclease free water), DNA wash solution (300 ul 70% ethanol), and DNA precipitation buffer (300 ul 80% ethanol, 5 mM potassium phosphate, pH 8.5). Each solution was pipetted sequentially into the tubing and separated from the next by an 8 ul air gap (4 mm in length). For additional details see Bordelon et al [8].

For 1 mL samples (including the surrogate urine samples), urine was drawn into the bulb of the 5 mL urine collection pipette, which was shaken vigorously by hand for 30 seconds to dissolve the lyophilized salts, then gently for 30 seconds to allow DNA adsorption to the silica surface of the beads. For 5 mL urine samples, urine was drawn into the bulb of the 15 mL urine collection pipette, which was shaken vigorously by hand for 30 s to dissolve the lyophilized salts, then allowed to sit for approximately 2 minutes with intermittent shaking by hand to allow DNA adsorption to the silica surfaces of the beads.

Next, the tip of the transfer pipette was inserted into the end of the preloaded small diameter FEP tubing, and a 2.5 cm3 neodymium magnet was used to collect the magnetic beads and transfer them through the pipette stem and into the DNA precipitation buffer. Once the beads were loaded into the small diameter tubing, the transfer pipette was removed and the end sealed with Hemato-Seal Tube Sealing Compound (Fisher Scientific catalog # 02-678). The sealed tubing was wrapped around a plastic cassette, which was inserted into a previously described automated sample processor [9]. The extraction program was run until the magnetic beads exited the elution chamber, at which point the tubing was removed from the plastic cassette, and the eluate was collected in a 0.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. Extracted TB and mouse DNA was detected using PCR as described below.

Detection of TB IS6110 DNA and mouse GAPDH DNA by PCR

A 67 bp amplicon of the IS6110 sequence was amplified using forward primer 5′-ACCAGCACCTAACCGGCTGTGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GTAGGCGAACCCTGCCCAGGTC-3′ [12]. A 95 bp amplicon of the mouse GAPDH sequence was amplified using forward primer 5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA-3′ (PrimerBank ID 126012538c1) [14]. The TB IS6110 (PCR efficiency = 1.95) and mouse GAPDH (PCR efficiency = 1.79) sequences were amplified in separate parallel reactions. A cycle threshold (Ct) of less than 30 for the mouse GAPDH reaction was reported as detectable.

For Peruvian samples and surrogate patient samples, amplification reactions were performed in a 25 ul volume using 5 ul of extraction eluate and the Qiagen QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (catalog # 204143). Briefly, for 25 ul reactions the final concentrations of each PCR reagent were: 1X Qiagen QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, 400 nM forward primer and 400 nM reverse primer (same concentration for both GAPDH and IS6110). Reactions were prepared in 200 ul PCR tubes (Thermo Scientific catalog # AB0620). Thermal cycling consisted of 95°C for 15 min to activate the Taq DNA polymerase and 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s using a Rotor-Gene Q thermal cycler. Reaction Ct values were recorded by Rotor-Gene Q software.

For South African samples, amplification reactions were performed in a 25 ul volume using 5 ul of extraction eluate and the Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific catalog #K0221) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, for 25 ul reactions the final concentrations of each PCR reagent were: (1X Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix, 400 nM forward primer and 400 nM reverse primer (same concentration for both GAPDH and IS6110). Reactions were prepared in LightCycler 480 Multiwell Plate 96 white plates (Roche). Thermal cycling consisted of 95°C for 15 min to activate the Taq DNA polymerase and 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s using a Roche LightCycler 480. Reaction Ct values were recorded by LightCycler software.

Data and Statistical Analysis

For the extraction recovery of surrogate patient samples we quantified post-extracted samples using PCR with a standard curve. As described in our previous work, we took the ratio of the amount of DNA recovered after extraction divided by the amount of DNA spiked into the surrogate sample to obtain the fraction of DNA recovered [8].

Clinical samples were included in analyses only if spiked extraction/PCR DNA control amplified, indicating successful extraction of intact DNA and removal of PCR inhibitors. Differences in Ct values between groups were tested using the Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test. If the data passed testing for normality and equal variance, a t-test was performed. All statistical tests were two-sided and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot version 11.0 (San Jose, California).

Our initial analysis of the South African samples included all samples with the positive extraction/PCR control. Those samples that had indeterminate values for the TB IS6110 DNA were assigned a Ct value of 40 to indicate that insufficient product was formed before the end of the PCR program. We then conducted a sensitivity analysis on all the samples with the positive extraction/PCR control and excluded all indeterminate TB IS6110 samples. This resulted in the exclusion of 8 TB-uninfected samples and 12 TB-infected samples.

Assessing DNase activity of South African urine samples

The relative DNase activity of urine samples was determined using the DNaseAlert QC System (Thermo Fisher Scientific catalog # AM1970) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the lyophilized DNaseAlert substrate containing fluorescent DNA probes was resuspended in 1 ml TE buffer. Ten microliters of the DNaseAlert substrate was added to each of the wells of a 96-well plate and mixed with 10 ul of 10X NucleaseAlert Buffer. Finally, 40 ul of urine sample was diluted to 80 ul using nuclease free water and added to each well. Urine samples were prepared and measured in duplicate. The plate was incubated at room temperature for 18 h prior to measuring fluorescence on a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrometer (Agilent Technologies) using 535/556 nm excitation/emission wavelengths with excitation and emission slit widths of 10 and 5 nm, respectively. Urine sample fluorescence values were compared to a DNase negative control to confirm the presence of DNase activity.

Results

Using 1 mL surrogate patient samples, we recovered 46 + 6% (mean ± s.d.) of spiked IS6110 DNA and 36 + 3% of our extraction/PCR control DNA (n=3). Subsequently, extraction/PCR control DNA was lyophilized with DNA-silica adsorption buffer in urine collection pipettes used for analysis of clinical samples.

In 1 ml samples from Peru, extraction/PCR control DNA was detectable in 39 of the 40 samples (97.5%). However, there was no difference between TB-infected and uninfected patients in the Cts for TB IS6110 Tr-DNA (N=39, p=0.166) or extraction/PCR control DNA (N=39, p=0.164) detected by PCR.

In 5 mL samples from South Africa, extraction/PCR control DNA was detectable in 84 of 86 samples (97.7%). As described in the methods, those patient samples that had indeterminate values for the TB IS6110 Tr-DNA were assigned a Ct value of 40 to indicate that insufficient product was formed before the end of the PCR program. When these indeterminate values were included in the analysis there were no statistically significant differences noted for any group comparisons, i.e. there was no difference in the Ct for TB IS6110 Tr-DNA (N=84, p=0.600) or the Ct for extraction/PCR control DNA (N=84, p=0.394).

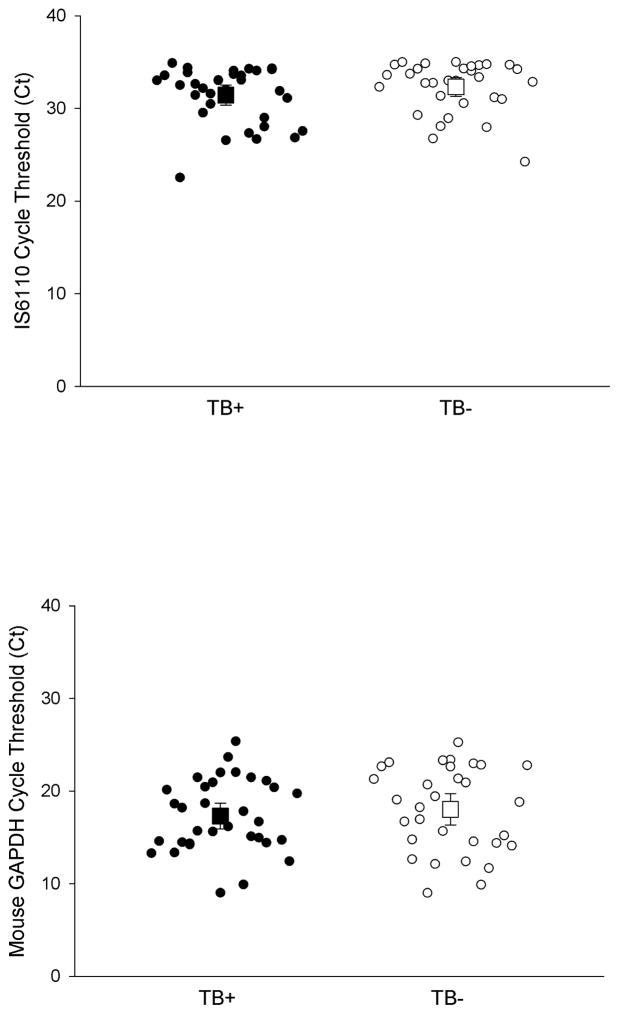

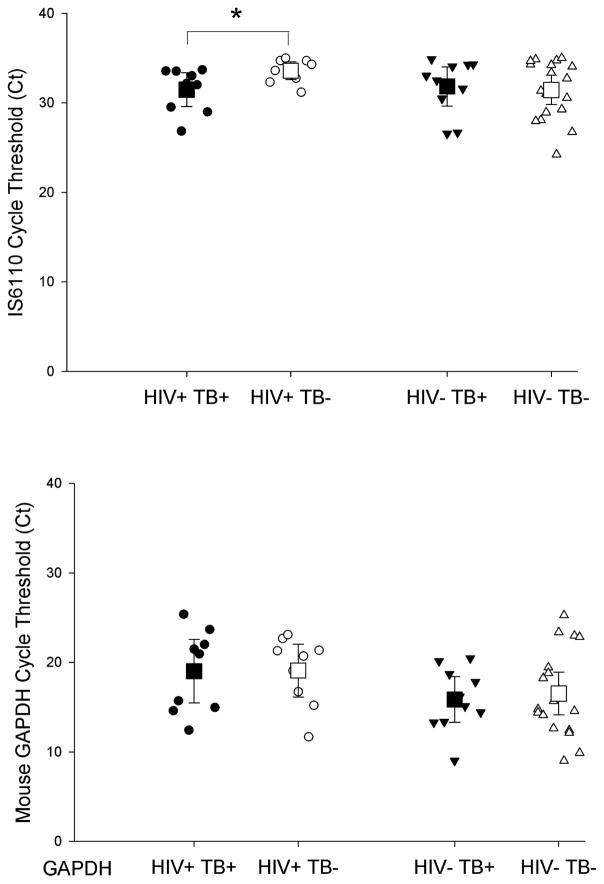

We then conducted an analysis on all the samples with the positive extraction/PCR control and excluded all indeterminate TB IS6110 samples (12 TB-infected and 8 TB-uninfected samples). When the indeterminate samples were removed there was no difference between TB IS6110 Tr-DNA amongst TB-infected (n=33) and TB-uninfected (n=31, p=0.132, Figure 1A) and there was no difference in the Ct of extraction/PCR control DNA detected (p=0.504, Figure 1B). We then removed samples with unknown HIV status (4 TB-uninfected and 14 TB-infected samples) in order to stratify the results by patient HIV status. There was an increase in TB IS6110 Tr-DNA among TB/HIV co-infected patients compared to TB-uninfected/HIV-infected patients, as indicated by a difference in Ct (N=18, p=0.037, Figure 2A). However, there was no difference in extraction/PCR control mouse DNA detected between these same samples (N=18, p=0.973, Figure 2B). There was no difference between the Ct of TB IS6110 Tr-DNA (Figure 2A, N=28, p=0.943) or mouse extraction/PCR control DNA (Figure 2B, 28, p=0.700) detected from TB-infected and TB-uninfected patients without HIV co-infection.

Figure 1. Detection of IS6110 Tr-DNA between TB-infected (TB+) and TB-uninfected (TB−) patients in Cape Town, South Africa.

(A) There was not a statistically significant increase in IS6110 Tr-DNA detected, corresponding to a lower cycle threshold (Ct), from TB-infected patients (n=33) compared to TB-uninfected patients (n=31, p=0.132). (B) There was no difference in mouse GAPDH DNA extraction/PCR control Ct between TB-infected (n=33) and TB-uninfected HIV+ patients (n=31, p=0.504). Mean and 95% confidence intervals shown.

Figure 2. Detection of IS6110 Tr-DNA among HIV-infected (HIV+) and HIV-uninfected (HIV−) patients in Cape Town, South Africa.

(A) Among HIV-infected patients there was a statistically significant increase in IS6110 Tr-DNA detected, corresponding to a lower cycle threshold (Ct), in TB-infected patients compared to TB-uninfected patients (N=18, p=0.037). There was no difference in mouse extraction/PCR control DNA Ct (B) between TB-infected (TB+) and TB-uninfected (TB−) HIV+ patients (N=18, P=0.973). Mean and 95% confidence intervals shown. Asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

Discussion

TB detection remains a significant diagnostic challenge. Worldwide in 2014, it is estimated that there were 9.6 million people infected with TB and 1.5 million deaths due to TB[15]. Of these deaths, more than one quarter were HIV-infected patients, a population where current diagnostics often fail [3,16]. TB diagnostics utilized in developing countries, where TB is most prevalent, depend on clinical screening algorithms [17] and sputum microscopy [18,19] which are limited by low sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity is particularly low in patients with HIV-coinfection from whom it is often difficult to obtain sputum samples [13,20,21]. Bacterial culture is used to confirm diagnosis, but slow turn-around and the need for facilities capable of performing this testing limit its utility. Peters et al [22] described detection of TB DNA biomarkers in urine as a potentially significant improvement to TB diagnosis, particularly if available in resource-limited countries. Urine is an ideal patient sample because it is easy to collect noninvasively, is available in large volumes, and is relatively safe compared to alternative samples such as sputum.

Several diagnostic assays are currently approved by the World Health Organization utilizing urine specimens [23,24]. Molecular testing using the Cepheid GeneXpert® MTB/RIF is increasing in high disease burden areas[13,25,26], and has been evaluated using urine samples [13,27,28] but sensitivity is variable, particularly among HIV-infected patients [21,25,26,29]. But implementation of GeneXpert has been limited by cartridge stock-outs, the need for a continuous electricity, temperature control during specimen transport, as well as human resource limitations [16,30–32]. A rapid test for lipoarabinomannan (LAM) using a lateral flow assay has also been increasingly used as a TB diagnostic tool using urine specimens [16]. This assay detects a component of the mycobacterial cell wall, however it does not allow for quantification of the biomarker which may be useful for to determine the best course for treatment. The poor sensitivity of LAM testing, especially among HIV-uninfected patients makes it a less desirable biomarker [13,33]. There is an urgent need for more rapid and simple nucleic acid based diagnostic tests to improve TB case detection and prevent further transmission of TB disease in developing countries [3,20,22,27].

In our study, we evaluated a simple-to-use, low-cost, and low-resource method for incorporating an extraction and PCR inhibition control in clinical urine samples. A 2009 review by Green, et. al[3], identified four critical steps in transrenal nucleic acid tests: 1) urine collection, 2) nucleic acid extraction, 3) nucleic acid amplification, and 4) detection and interpretation. Our extraction/PCR control DNA is designed to confirm nucleic acid extraction and PCR viability through product formation. As a consequence of our split sample design, this latter feature indicates there are no inhibitors of PCR present in the unknown sample and that PCR reagents are all viable. Our 67 bp control is also designed to reflect the DNA size dependence of magnetic bead extraction and agrees with the recommendation of Green et al [3] that Tr-DNA fragments are predicted to be less than 100 bp. Our control was successfully detected in 39 of 40 (97.5%) Peruvian samples and 84 of 86 (97.7%) South African clinical urine samples demonstrating the extraction/PCR control DNA was extracted and amplified. This is an important step forward for molecular urine TB diagnostic tests, given that the low cellularity of urine specimens precludes inclusion of endogenous DNA controls [3]. PCR Ct for the extraction/PCR control varied from 10 to 30. Presumably this variation is due to differences in backgrounds of clinical samples possibly resulting decreased DNA recovery or increased retention of PCR inhibitors. We hope to follow-up on this observation and its potential impact on the TB-infected Ct values in future studies.

In this study, the extraction/PCR control was detected in 97.6% of clinical samples indicating that this extraction/PCR control DNA strategy is a reliable means for excluding false negatives due to poor DNA extraction or PCR amplification failure due to PCR inhibitors. Despite the inclusion and success of this extraction/PCR control DNA, there was not a detectable difference in Ct between total TB-infected and TB-uninfected in either the Peruvian or South African samples. However, by stratifying these samples according to HIV status we detected an increase in TB IS6110 Tr-DNA between TB/HIV co-infected patients compared to TB-uninfected/HIV-infected patients, a finding that has been reported and summarized by other studies[3,22]. This finding may be due to an increased bacterial burden or more disseminated disease among HIV-infected persons [34] as shown by a LAM urine test [34]. It is uncertain how DNase activity may have affected these results, since a difference in TB IS6110 Tr-DNA was still detected among TB/HIV co-infected and TB-uninfected/HIV-infected persons despite the presence of DNases in all South African samples.

There are several potential reasons the TB biomarker is not consistently detected [3], and understanding these limitations may be useful for informing future studies. For example, urine storage conditions play an important role in the preservation of DNA biomarkers during the time between sample collection and sample processing [3,35–37]. We observed that all samples from South Africa were positive for DNase activity, which could account for high Ct values and lack of difference in IS6110 Tr-DNA between TB-infected and TB-uninfected samples. Despite DNase activity, the extraction/PCR control mouse DNA was preserved during the relatively short processing time since it was detected in 97.6% of samples. The preservation of the extraction/PCR control DNA despite the presence of DNase activity is likely due to the presence of guanidinium in the DNA-silica adsorption buffer lyophilized in the pipettes which has been shown to block DNase activity [13]. Guanidinium would therefore have helped to preserve the extraction/PCR mouse control DNA introduced from the lyophilized reagents as well as any IS6110 present in the sample, but would not have affected DNase degradation of IS6110 target fragments that occurred during sample collection or during storage. However, the addition of preservatives to inactivate or denature urine DNases upon sample collection would be expected to better preserve DNA biomarkers during the time between sample collection and sample processing. The addition of DNA-silica binding buffer directly to the sample could be useful if DNA extraction is the only intended use for the urine, but guanidinium could potentially interfere with other analyses, such as LAM detection, by altering structural confirmations [28]. Alternatively, adding 40 mM EDTA upon collection and subsequently adding DNA-silica adsorption buffer immediately prior to extraction would be ideal and has been performed in other studies [35–38], although it has also been noted that the addition of EDTA does not always prevent degradation in urine samples [39].

Increasing the urine volume may also help to increase biomarker detection. It is reasonable to assume that larger sample volumes contain higher numbers of target biomarker and would, therefore, increase the likelihood of detection. There is some precedent for pursuing this approach since Lawn et al. [13,20] report increased detection by the Gene Xpert with sample volumes on the order of 50 ml compared to a 2 ml volume. In results reported here, samples tested from Peru were provided in 1 ml aliquots and from South Africa in 5 ml aliquots. These are relatively small volumes compared to a typical void volume and may have contributed to a lack of a difference between TB-infected and uninfected samples observed in this study. For example, because we did not see a difference in Ct between uninfected and infected TB samples from Peru, we increased the sample volume. Scale-up from the 1 and 5 ml urine samples available for these studies to 50 or 100 ml urine samples is a relatively easy modification with this approach, though it is likely to increase the time for binding to the beads and for the beads to survey the entire sample.

There are several limitations to this study. Our previous work [8,9,31] describes the extraction of DNA and RNA using this technology. Based on this work, we think the differences in extraction recovery (46% for IS6110 vs 36% for extraction/PCR control) may be due in part to the difference in length between the DNA sequences. The mouse GAPDH sequence is 120 bp compared to the TB IS6110 which is 140 bp. In [8] we demonstrated that longer sequences are able to bind the silane coated Dynabeads better than shorter sequences. However our previous related work [8,31] found the nucleic acid recovery from our method is comparable to two commercial kits (Qiagen RNeasy and Norgen).

Ideally, we would assay for IS6110 and the extraction/PCR control DNA in a single PCR reaction. Unfortunately we were unable to get a consistent duplexed reaction using hydrolysis probes ready in time to use it with samples from Peru or the samples we processed in South Africa. When we traveled to South Africa we were unable to purchase the Qiagen QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit, so we substituted the Thermo Fisher Maxima SYBR PCR kit. Our collaborators in South Africa did not have the Qiagen Rotor-Gene Q thermal cyclers, so we used the Roche LightCycler 480 thermal cycler which was available. In an effort to be as consistent as possible we did not change the protocol or cycling conditions for the PCR, and we shipped our previously described asynchronous extraction device to South Africa.

In this study we report Ct values for IS6110 in TB-culture negative samples. Amplification approaches such as PCR can produce non-specific products through primer annealing errors or reaction temperature errors. When using intercalating dyes, both specific and non-specific products contribute to observed fluorescence affecting the Ct value. The use of hydrolysis probes is able to minimize these errors [30]. However, we used SYBR green in this in this study so detection of a PCR product at high Ct does not necessarily indicate the presence of IS6110. We ran gels on some of the South African samples and the PCR product was banded indicating more PCR products than just the expected TB IS6110 product were amplified (data not shown).

This asynchronous extraction device is a simple-to-use, inexpensive means of reliably extracting DNA from clinical urine samples in resource-limited settings and incorporating an extraction/PCR control. Even with the inclusion of the extraction/PCR control DNA, the only significant differences in Tr-DNA we found was that TB IS6110 Tr-DNA level was increased among TB/HIV co-infected persons compared to TB-uninfected/HIV-infected persons, a finding that has been reported in other studies. The inclusion of an extraction/PCR control DNA worked well, but would have had even greater utility if it had been added during sample collection to also indicate any DNA degradation during processing or storage. Further studies with prospectively gathered samples are required to determine if our proposed extraction/PCR control DNA can also be used to indicate DNA has not been degraded between the time of sample collection and testing and, thus, help to identify sample additives that reduce further degradation of any IS6110 Tr-DNA contained within the urine sample.

Highlights.

Designed/tested spike DNA control for extraction/removal of PCR inhibitors for acellular samples

Extraction/PCR control DNA performed well and was detectable in 97% of urine samples

No differences in transrenal DNA between TB+ and TB− retrospective samples were observed

TB−/HIV+ and TB+/HIV+ were statistically different as reported by others

Control DNA may improve transrenal DNA detection in clinical samples when included at collection

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [K08AI104352, A.C.P.] the National Research Foundation, RSA, through a South African Research Chair Initiative grant (J.B.), Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA [OPP 1028749, F.R.H & D.W.W], and urine sample collection by a grant from the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trial Partnership [TB-NEAT, K.D.].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.van der Zee A, Roorda L, Bosman G, Ossewaarde JM. Molecular Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infections by Semi-Quantitative Detection of Uropathogens in a Routine Clinical Hospital Setting. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwasaki H, Chagan-Yasutan H, Leano PS, Koizumi N, Nakajima C, et al. Combined antibody and DNA detection for early diagnosis of leptospirosis after a disaster. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;84:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green C, Huggett JF, Talbot E, Mwaba P, Reither K, et al. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis through the detection of mycobacterial DNA in urine by nucleic acid amplification methods. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:505–511. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andries AC, Duong V, Ly S, Cappelle J, Kim KS, et al. Value of Routine Dengue Diagnostic Tests in Urine and Saliva Specimens. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Southern TR, Racsa LD, Albarino CG, Fey PD, Hinrichs SH, et al. Comparison of FilmArray and Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase PCR for Detection of Zaire Ebolavirus from Contrived and Clinical Specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2956–2960. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01317-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gourinat AC, O’Connor O, Calvez E, Goarant C, Dupont-Rouzeyrol M. Detection of Zika virus in urine. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:84–86. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.140894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarhan RM, Kamel HH, Saad GA, Ahmed OA. Evaluation of three extraction methods for molecular detection of Schistosoma mansoni infection in human urine and serum samples. J Parasit Dis. 2015;39:499–507. doi: 10.1007/s12639-013-0385-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bordelon H, Russ PK, Wright DW, Haselton FR. A magnetic bead-based method for concentrating DNA from human urine for downstream detection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bitting AL, Bordelon H, Baglia ML, Davis KM, Creecy AE, et al. Automated Device for Asynchronous Extraction of RNA, DNA, or Protein Biomarkers from Surrogate Patient Samples. J Lab Autom. 2016;21:732–742. doi: 10.1177/2211068215596139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aceti A, Zanetti S, Mura MS, Sechi LA, Turrini F, et al. Identification of HIV patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis using urine based polymerase chain reaction assay. Thorax. 1999;54:145–146. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sechi LA, Pinna MP, Sanna A, Pirina P, Ginesu F, et al. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by PCR analysis of urine and other clinical samples from AIDS and non-HIV-infected patients. Mol Cell Probes. 1997;11:281–285. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1997.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannas A, Goletti D, Girardi E, Chiacchio T, Calvo L, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA detection in soluble fraction of urine from pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:146–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Englen MD, Kelley LC. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for the identification of Campylobacter jejuni by the polymerase chain reaction. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2000;31:421–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spandidos A, Wang X, Wang H, Seed B. PrimerBank: a resource of human and mouse PCR primer pairs for gene expression detection and quantification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D792–799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng J, Pei J, Gou H, Ye Z, Liu C, et al. Rapid and simple detection of Japanese encephalitis virus by reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification combined with a lateral flow dipstick. J Virol Methods. 2015;213:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peter JG, Zijenah LS, Chanda D, Clowes P, Lesosky M, et al. Effect on mortality of point-of-care, urine-based lipoarabinomannan testing to guide tuberculosis treatment initiation in HIV-positive hospital inpatients: a pragmatic, parallel-group, multicountry, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reid MJ, Shah NS. Approaches to tuberculosis screening and diagnosis in people with HIV in resource-limited settings. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:173–184. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70043-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Getahun H, Harrington M, O’Brien R, Nunn P. Diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in people with HIV infection or AIDS in resource-constrained settings: informing urgent policy changes. Lancet. 2007;369:2042–2049. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perkins MD, Cunningham J. Facing the crisis: improving the diagnosis of tuberculosis in the HIV era. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(Suppl 1):S15–27. doi: 10.1086/518656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davids M, Dheda K, Pant Pai N, Cogill D, Pai M, et al. A Survey on Use of Rapid Tests and Tuberculosis Diagnostic Practices by Primary Health Care Providers in South Africa: Implications for the Development of New Point-of-Care Tests. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peter JG, Theron G, Muchinga TE, Govender U, Dheda K. The diagnostic accuracy of urine-based Xpert MTB/RIF in HIV-infected hospitalized patients who are smear-negative or sputum scarce. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peter J, Green C, Hoelscher M, Mwaba P, Zumla A, et al. Urine for the diagnosis of tuberculosis: current approaches, clinical applicability, and new developments. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16:262–270. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328337f23a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO. Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB in adults and children. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO. The use of lateral flow urine lipoarabinomannan assay (LF-LAM) for the diagnosis and screening of active tuberculosis in people living with HIV. Geneva, Switzerland: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjerrum S, Kenu E, Lartey M, Newman MJ, Addo KK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the rapid urine lipoarabinomannan test for pulmonary tuberculosis among HIV-infected adults in Ghana-findings from the DETECT HIV-TB study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:407. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1151-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaCourse SM, Cranmer LM, Matemo D, Kinuthia J, Richardson BA, et al. Tuberculosis Case Finding in HIV-Infected Pregnant Women in Kenya Reveals Poor Performance of Symptom Screening and Rapid Diagnostic Tests. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71:219–227. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dheda K, Barry CE, 3rd, Maartens G. Tuberculosis. Lancet. 2016;387:1211–1226. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00151-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lombardero M, Heymann PW, Platts-Mills TA, Fox JW, Chapman MD. Conformational stability of B cell epitopes on group I and group II Dermatophagoides spp. allergens. Effect of thermal and chemical denaturation on the binding of murine IgG and human IgE antibodies. J Immunol. 1990;144:1353–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawn SD, Kerkhoff AD, Burton R, Schutz C, van Wyk G, et al. Rapid microbiological screening for tuberculosis in HIV-positive patients on the first day of acute hospital admission by systematic testing of urine samples using Xpert MTB/RIF: a prospective cohort in South Africa. BMC Med. 2015;13:192. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0432-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arya M, Shergill IS, Williamson M, Gommersall L, Arya N, et al. Basic principles of real-time quantitative PCR. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2005;5:209–219. doi: 10.1586/14737159.5.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bordelon H, Adams NM, Klemm AS, Russ PK, Williams JV, et al. Development of a low-resource RNA extraction cassette based on surface tension valves. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2011;3:2161–2168. doi: 10.1021/am2004009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ardizzoni E, Fajardo E, Saranchuk P, Casenghi M, Page AL, et al. Implementing the Xpert(R) MTB/RIF Diagnostic Test for Tuberculosis and Rifampicin Resistance: Outcomes and Lessons Learned in 18 Countries. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanifa Y, Fielding KL, Chihota VN, Adonis L, Charalambous S, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Lateral Flow Urine LAM Assay for TB Screening of Adults with Advanced Immunosuppression Attending Routine HIV Care in South Africa. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dheda K, Davids V, Lenders L, Roberts T, Meldau R, et al. Clinical utility of a commercial LAM-ELISA assay for TB diagnosis in HIV-infected patients using urine and sputum samples. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milde A, Haas-Rochholz H, Kaatsch HJ. Improved DNA typing of human urine by adding EDTA. Int J Legal Med. 1999;112:209–210. doi: 10.1007/s004140050237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ingersoll J, Bythwood T, Abdul-Ali D, Wingood GM, Diclemente RJ, et al. Stability of Trichomonas vaginalis DNA in urine specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1628–1630. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02486-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cannas A, Kalunga G, Green C, Calvo L, Katemangwe P, et al. Implications of storing urinary DNA from different populations for molecular analyses. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petrucci R, Lombardi G, Corsini I, Visciotti F, Pirodda A, et al. Use of transrenal DNA for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in children: a case of tubercular otitis media. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:336–338. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02548-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janvier F, Delaune D, Poyot T, Valade E, Merens A, et al. Ebola Virus RNA Stability in Human Blood and Urine in West Africa’s Environmental Conditions. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:292–294. doi: 10.3201/eid2202.151395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]