Abstract

Objective To compare the effectiveness of the oxytocin receptor antagonist atosiban with the beta mimetic fenoterol as uterine relaxants in women undergoing external cephalic version (ECV) for breech presentation.

Design Multicentre, open label, randomised controlled trial.

Setting Eight hospitals in the Netherlands, August 2009 to May 2014.

Participants 830 women with a singleton fetus in breech presentation and a gestational age of more than 34 weeks were randomly allocated in a 1:1 ratio to either 6.75 mg atosiban (n=416) or 40 μg fenoterol (n=414) intravenously for uterine relaxation before ECV.

Main outcome measures The primary outcome measures were a fetus in cephalic position 30 minutes after the procedure and cephalic presentation at delivery. Secondary outcome measures were mode of delivery, incidence of fetal and maternal complications, and drug related adverse events. All analyses were done on an intention-to-treat basis.

Results Cephalic position 30 minutes after ECV occurred significantly less in the atosiban group than in the fenoterol group (34% v 40%, relative risk 0.73, 95% confidence interval 0.55 to 0.93). Presentation at birth was cephalic in 35% (n=139) of the atosiban group and 40% (n=166) of the fenoterol group (0.86, 0.72 to 1.03), and caesarean delivery was performed in 60% (n=240) of women in the atosiban group and 55% (n=218) in the fenoterol group (1.09, 0.96 to 1.20). No significant differences were found in neonatal outcomes or drug related adverse events.

Conclusions In women undergoing ECV for breech presentation, uterine relaxation with fenoterol increases the rate of cephalic presentation 30 minutes after the procedure. No statistically significant difference was found for cephalic presentation at delivery.

Trial registration Dutch Trial Register, NTR 1877.

Introduction

Breech presentation occurs in up to 4% of singleton pregnancies at term. Since publication of the Term Breech Trial in 2000, elective caesarean section has been the dominant mode of delivery in most countries.1 2 3 In 2015 the World Health Organization reported that globally caesarean delivery was overused.4 5 Breech presentation is the third most common indication for elective caesarean delivery.6 External cephalic version (ECV) is a safe obstetrical procedure that reduces the risk of a non-cephalic birth and caesarean delivery by approximately 50%.7 In 2014 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine published a joint consensus statement on the safe prevention of elective caesarean delivery, in which ECV is highly recommended.6 This is especially relevant in low and middle income countries where the effects of caesarean delivery on morbidity and mortality are more severe.8

Several methods have been proposed to enhance the outcome of ECV, including uterine relaxation with tocolytic drugs, epidural or spinal analgesia, and amnio-infusion, as well as complementary methods such as vibro-acoustic stimulation, acupuncture, and moxibustion.9 Drug induced uterine relaxation using nitric oxide, beta mimetics, calcium channel antagonists, or oxytocin receptor antagonists, can increase the success rate of ECV.6 10 Most studies evaluating the effectiveness of tocolysis have used beta mimetics (nine studies of beta mimetics versus placebo, pooled relative risk 1.6 (95% confidence interval 1.2 to 2.0) for cephalic presentation after ECV attempt).9 However, beta mimetics have known adverse maternal cardiovascular side effects such as flushing and palpitations.9

Randomised trial data show that nifidepine, a calcium channel blocker, is not effective for increasing cephalic presentation after ECV compared with no drugs (1.1, 0.85 to 1.5).11 Atosiban, an oxytocin receptor antagonist, has no cardiovascular side effects and is becoming more widely used for ECV, yet no randomised controlled trial has assessed its effectiveness. We compared the effectiveness of atosiban with the beta mimetic fenoterol for achieving a cephalic presentation 30 minutes after ECV and cephalic presentation at delivery.

Methods

Study design and participants

We performed a multicentre, open label, randomised controlled trial in one academic and seven teaching hospitals in the Netherlands. Together, these hospitals are responsible for 16 000 increased risk deliveries a year, with annual hospital delivery rates ranging from 1500 to 3000. We followed the CONSORT guidelines to report this study.

Women with a singleton fetus in breech position who were scheduled for ECV were eligible for the study. Exclusion criteria were maternal age less than 18 years, gestational age less than 32 weeks, any contraindication to vaginal birth (such as placenta praevia), any contraindication for ECV according to the Guideline of the Dutch Association for Obstetrics and Gynaecology (scarred uterus other than transverse in the lower segment, known uterine anomalies, history or signs of placental abruption, severe pre-eclampsia or HELLP syndrome, bleeding less than seven days before ECV attempt, and ruptured membranes),12 any known contraindication to one of the two study drugs, suspected intrauterine growth restriction (defined as estimated fetal weight less than the fifth centile for gestational age assessed by ultrasonography), severe oligohydramnios (deepest pool <2 cm), fetal anomalies, or non-reassuring fetal heart rate. Midwives, residents, or gynaecologists identified eligible women. After counselling and reading the patient information form, patients were asked for written informed consent.

Randomisation

The women were randomly allocated (1:1) to receive atosiban (intervention group) or fenoterol (control group). An independent data manager assigned the women to groups based on a computer generated random sequence, stratified by hospital and parity. EVC was scheduled within seven days after randomisation. Participants and investigators were aware of allocation; blinding was not possible owing to obvious maternal side effects that commonly occur with fenoterol, such as tachycardia, dizziness, and flushing.

Interventions

In each hospital, a team of experienced obstetricians and midwives performed the ECV. A trained sonographer, obstetrician, or midwife carried out ultrasonography to assess the position of the fetus, including type of breech (frank, complete, or footling), location of the placenta, estimation of fetal weight, and estimation of amniotic fluid volume, including measurement of the largest pocket depth. Fetal wellbeing was established with electronic fetal heart rate monitoring for at least 30 minutes before and after ECV. Fifteen minutes before ECV a doctor gave the mother an intravenous bolus of atosiban (6.75 mg) or fenoterol (40 μg). ECV could comprise a forward and a backward roll. Fetal heart rate was monitored intermittently with ultrasonography. The duration of any fetal bradycardia was registered. Women with non-sensitised Rh negative blood received anti-D immunoglobulin (1000 IU intramuscularly) after ECV.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measures were cephalic presentation 30 minutes after the procedure, confirmed by ultrasonography, and cephalic presentation at delivery. Secondary outcomes were mode of delivery, incidence of fetal and maternal complications, and study drug related adverse events. Complications were persistent non-reassuring fetal heart rate on cardiotocography, occult or overt umbilical cord prolapse, placental abruption, and emergency delivery. Adverse events due to atosiban or fenoterol were chest pain, nausea, vomiting, headache, flushing, dizziness, hypotension (associated with fainting or abnormalities of fetal heart rate), tachycardia resulting in palpitations, local skin reaction on injection of the drug, anaphylactic shock, and cessation of treatment because of side effects.

Post hoc outcomes were gestational age at delivery, time to delivery, admission to neonatal intensive care for more than 24 hours, Apgar score less than 7 at five minutes, birth weight, blood loss, and maternal blood transfusion, postpartum hospital stay (in days), and postpartum complications, defined as puerperal fever, (suspected) endometritis, mastitis, operation for removal of placental tissue, or pulmonary embolism. Appendix table 1 lists all outcomes.

The data were collected on web based electronic case record forms, and uploaded cases were stored in a database. Paper delivery forms were supplied to participants who did not deliver in a participating hospital, and their primary caretakers, such as midwives in primary care settings, were asked to ensure that these forms were returned after the study.

Sample size

The trial was designed to detect a 10% improvement in the primary outcome of cephalic presentation 30 minutes after ECV, assuming a 50% success rate in the fenoterol group (β error 20%, α error 5%, two sided test). We calculated that 806 women needed to be randomised to show an improvement from 50% to 60% with atosiban.

Analysis

To ensure intention-to-treat analysis, we carried out five imputations on the primary outcome using baseline covariates. The primary analysis was subsequently performed on imputed datasets, and we pooled estimates from these datasets using Rubin’s rule. Complete case analysis was used to analyse secondary outcomes. Baseline data were analysed descriptively for the women and their pregnancies. The χ2 test was used to compare the rates of the primary and secondary outcomes between the two groups. We considered a P value of less than 0.05 to indicate statistical significance. For each outcome we calculated relative risks and appropriate 95% confidence intervals.

We performed three retrospective sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome of cephalic presentation 30 minutes after ECV. The first was a complete case analysis. The second sensitivity analysis was performed because of an imbalance in baseline characteristics despite randomisation. We adjusted the imputed data for age, parity, gestational age at ECV, ethnicity, body mass index, estimated fetal weight, type of breech presentation, location of the placenta, and estimated amniotic fluid index. A third retrospective analysis was performed to evaluate the robustness of the treatment effect on cephalic presentation 30 minutes after ECV between centres. The results were pooled into relative risks, and heterogeneity was explored in a random effects meta-analysis model. To evaluate safety, an interim analysis was planned for when half of the patients had been recruited. Serious adverse events were reported to an independent data safety monitoring board. They noted no conditions to stop the trial.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. The results will be used in a guideline and will be added to patient information brochures.

Results

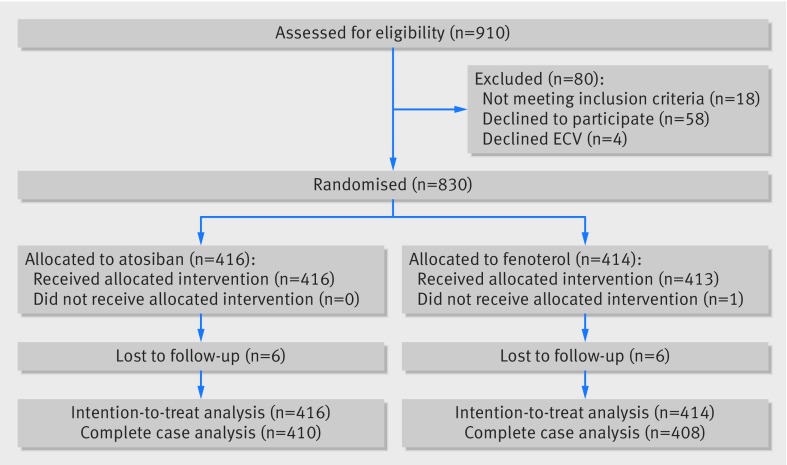

Between August 2009 and May 2014, 830 women were enrolled and randomised; 416 to atosiban (intervention group) and 414 to fenoterol (control group). The mean gestational age at which ECV was performed was 36 weeks, and 62% of the women were nulliparous. Baseline characteristics were comparable between the two groups (table 1). For the complete case analysis, primary outcome data were available for 410 women in the atosiban group and 408 in the fenoterol group (fig 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants by intervention group for complete case analysis. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Atosiban (n=410) | Fenoterol (n=408) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 32.1 (4.0) | 32.4 (4.3) |

| Multiparous women | 154 (38) | 153 (37) |

| Mean (SD) gestational age at ECV (weeks) | 35.8 (0.9) | 35.9 (1.0) |

| White ethnicity | 350 (85.4) | 355 (87.0) |

| Mean (SD) body mass index | 24.1 (4.3) | 24.2 (4.8) |

| Mean (SD) estimated fetal weight (g)* | 2622 (391.0) | 2572 (457.5) |

| Frank breech presentation† | 300 (76) | 273 (70) |

| Anterior placenta‡ | 127 (33) | 144 (37) |

| Mean (SD) estimated amniotic fluid index§ | 13.8 (4.9) | 13.7 (4.7) |

ECV=external cephalic version.

*Missing data: n=234 for atosiban, n=250 for fenoterol.

†Missing data: n=392 for atosiban, n=391 for fenoterol.

‡Missing data: n=386 for atosiban, n=386 for fenoterol.

§Missing data: n=263 for atosiban, n=281 for fenoterol.

Fig 1 Randomisation, treatment, and follow-up of participants

The primary outcome of cephalic presentation 30 minutes after ECV occurred in 34% (n=140) of women in the atosiban group compared with 40% (n=166) in the fenoterol group (0.73, 0.55 to 0.93). At delivery, 35% (n=139) of fetuses in the atosiban group and 40% (n=160) in the fenoterol group were in the cephalic position (0.86, 0.72 to 1.03). Caesarean delivery was performed in 60% (n=240) of women in the atosiban group and 55% (n=218) in the fenoterol group (1.09, 0.96 to 1.22; table 2).

Table 2.

Results for primary and secondary outcomes in intention-to-treat analysis

| Outcomes | Atosiban (n=416) | Fenoterol (n=414) | Relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cephalic presentation 30 minutes after ECV (No; %)* | 140 (34) | 166 (40) | 0.73 (0.55 to 0.93) |

| Cephalic presentation at delivery (No; %)† | 139 (35) | 160 (40) | 0.86 (0.72 to 1.03) |

| Mode of delivery‡ | |||

| Vaginal delivery (No; %): | 163 (40) | 180 (45) | 0.89 (0.76 to 1.05) |

| Spontaneous | 146 | 167 | |

| Instrumental | 17 | 13 | |

| Caesarean delivery (No; %): | 240 (60) | 218 (55) | 1.09 (0.96 to 1.22) |

| Elective | 199 | 158 | |

| No progress of labour | 27 | 26 | |

| Suspected fetal distress | 4 | 21 | |

| Other | 10 | 13 |

ECV=external cephalic version.

*Imputation for primary outcome.

†Missing data: n=402 for atosiban, n=397 for fenoterol.

‡Missing data: n=403 for atosiban, n=398 for fenoterol.

In the atosiban group, of the 139 women with a fetus in the cephalic position at delivery, 109 (78%) had a spontaneous vaginal delivery, 15 (11%) an instrumental delivery, and 9 (6%) an intrapartum caesarean delivery. In the fenoterol group, of the 160 women with a fetus in the cephalic position at delivery, 125 (78%) had a spontaneous vaginal delivery, 13 (8%) an instrumental delivery, and 19 (12%) an intrapartum caesarean delivery. Emergency caesarean delivery for suspected fetal distress was more common in the fenoterol group: two cases immediately after ECV and 19 during labour. In the atosiban group, four of the 204 women who had planned a vaginal birth had emergency caesarean delivery for suspected intrapartum fetal distress compared with 19 of 218 participants in the fenoterol group (relative risk 0.75, 95% confidence interval 0.24 to 1.29).

The frequency of poor fetal and maternal complications did not differ between the two groups (table 3). The average time between ECV and delivery was 22 days in both groups. Labour was induced only for additional indications such as hypertension. No perinatal or neonatal mortality occurred in the atosiban group, whereas two children died in the fenoterol group. One neonate, born five weeks after ECV, died of an autosomal recessive congenital disorder. The other baby died two hours after a vacuum assisted delivery for prolonged second stage of labour. ECV had been performed five weeks before labour. The baby had normal Apgar scores (9 at five minutes), and autopsy did not reveal cause of death.

Table 3.

Neonatal and maternal outcomes in complete case analysis. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Outcomes | Atosiban (n=410) | Fenoterol (n=408) | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 38.9 (1.3) | 38.9 (1.9) | 0.70 | |

| Mean (SD) mean time to delivery (days) | 22 (9.1) | 22 (9.6) | - | 0.23 |

| Fetal mortality | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | - |

| Neonatal mortality | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | - | 0.15 |

| Admission to neonatal intensive care for >24 hours* | 16 (0.4) | 17 (0.4) | 0.94 (0.48 to 1.8) | - |

| Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes† | 6 (1) | 13 (3) | 0.45 (0.17 to 1.20) | - |

| Mean (SD) birth weight (g)‡ | 3356 (460) | 3364 (523) | - | 0.81 |

| Female | 204 (50) | 204 (50) | 1.00 (0.87 to 1.14) | - |

| Mean (SD) blood loss (mL)§ | 474 (473.2) | 470 (447.3) | - | 0.92 |

| Women requiring blood transfusions¶ | 6 (1) | 7 (2) | 0.86 (0.29 to 2.5) | - |

| Mean (SD) maternal postpartum hospital stay (days)** | 290 (3.1) | 287 (3.1) | - | 0.94 |

| Maternal postpartum complications†† | 15 (4) | 16 (4) | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.9) | - |

*Missing data: n=399 for atosiban, n=397 for fenoterol.

†Missing data: n=399 for atosiban, n=397 for fenoterol.

‡Missing data: n=394 for atosiban, n=396 for fenoterol.

§Missing data: n=390 for atosiban, n=389 for fenoterol.

¶Missing data: n=400 for atosiban, n=401 for fenoterol.

**Missing data: n=398 for atosiban, n=395 for fenoterol.

††Missing data: n=385 for atosiban, n=386 for fenoterol. Complications: puerperal fever, (suspected) endometritis, mastitis, operation for remove placental tissue, and pulmonary embolism.

The frequency of fetal and maternal complications after ECV did not differ significantly between groups (table 4). No woman required emergency delivery in the atosiban group but two did in the fenoterol group. In one woman, the fetal heart rate was non-reassuring after an ECV attempt, and in the other woman, ultrasonography showed the umbilical cord to be lying in front of the fetal head after successful ECV. No drug related adverse events were reported in the atosiban group. The procedure was stopped in one woman in the fenoterol group because she experienced severe hypotension. A significant difference in side effects was found between the groups, with 15 women (5%) in the atosiban group compared with 209 women (71%) in the fenoterol group experiencing palpitations (0.07, 0.04 to 0.12).

Table 4.

Complications of external cephalic version (ECV) and drug related adverse events in complete case analysis. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Complications | Atosiban (n=410) | Fenoterol (n=408) | Relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-reassuring fetal heart rate after ECV attempt resulting in emergency delivery* | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | - |

| Placental abruption† | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Emergency delivery‡ | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | - |

| Adverse events due to medication§ | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | - |

| Cessation of treatment due to side effects¶ | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | - |

| Minor side effects** | 86 (30.0) | 224 (75.7) | 0.40 (0.33 to 0.48) |

| Palpitations†† | 15 (5) | 209 (71) | 0.07 (0.04 to 0.12) |

| Dizziness‡‡ | 25 (9) | 55 (19) | 0.47 (0.30 to 0.73) |

| Flushes§§ | 17 (6) | 99 (34) | 0.18 (0.11 to 0.29) |

Minor side effects were defined as one or a combination of: palpitations, nausea, vomiting, headaches, flushing, and dizziness.

*Missing data: n=402 for atosiban and n=399 for fenoterol owing to missing data.

†Missing data: n=392 for atosiban, n=390 for fenoterol.

‡Missing data: n=391 for atosiban, n=391 for fenoterol.

§Missing data: n=399 for atosiban, n=396 for fenoterol.

¶Missing data: n=399 for atosiban, n=396 for fenoterol.

**Missing data: n=287 for atosiban, n=296 for fenoterol.

††Missing data: n=287 for atosiban, n=296 for fenoterol.

‡‡Missing data: n=285 for atosiban, n=292 for fenoterol.

§§Missing data: n=287 for atosiban, n=295 for fenoterol.

Complete case analysis showed a significant difference in favour of fenoterol for cephalic presentation 30 minutes after ECV (0.82, 0.69 to 0.98). After adjustment for baseline characteristics the odds ratio for successful ECV was 0.85 (0.72 to 1.02). The pooled result of the post hoc analysis indicated a consistent treatment effect and no heterogeneity was identified among centres (0.82, 0.69 to 0.98), I2=0%) (see supplementary appendix 1).

Discussion

In this randomised controlled trial of 818 women with singleton pregnancies of more than 34 weeks’ gestation, uterine relaxation with atosiban for external cephalic version (ECV) resulted in a lower rate of fetuses in the cephalic position after 30 minutes compared with fenoterol. This led to a higher risk of caesarean deliveries after atosiban treatment than after fenoterol treatment. Although the difference was not statistically significant, the increased risk is highly plausible given the lower rate of successful ECV with atosiban.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A beta mimetic rather than placebo was used for the control because at the start of the trial it was the best treatment in a clinical setting, with a 10% absolute increase in cephalic presentations at delivery.9 To allow the drugs to reach a full therapeutic blood concentration and to overcome unintended protocol violations, we used the same protocol for both drugs; ECV was started 15 minutes after the drug was given. The mean time for both drugs to reach their maximum concentrations in serum is 30 minutes, with a half life of 1.4 hours for atosiban and 2 hours for fenoterol.13 14 15 16 17

A limitation of our study is that the doctors and the women could not be blinded to treatment owing to the obvious and common side effects of beta mimetics. However, side effects were never a reason for stopping the intervention, and bias due to non-blinding was virtually absent.

Our success rate for cephalic presentations at 30 minutes after ECV was lower than anticipated,9 which might be due to the referral of some women after an initial unsuccessful attempt by independent midwives in an out of hospital setting. A cohort study of ECV attempts by midwives outside the hospital setting in the Netherlands reported a higher success rate than ours (1093 of 2318 women; 41%).18 The success rate in our study corresponds to that in other cohort studies and randomised controlled trials comparing tocolytic agents.10 11 19 20 Our sample size calculation was still adequate to detect the anticipated increase in cephalic presentations at 30 minutes after ECV, as lower or higher baseline rates have more statistical power to detect similar changes of 10% absolute risk difference.

Even though there was a difference in effect size between the imputed analysis and complete case analysis, the results are still likely to be generalisable. Missing data were balanced between groups and assumed to be random. We included a wide range of both positive and negative predictors for successful ECV in our imputation model. Correction for confounding from potential baseline imbalance showed a strong correlation between baseline characteristics and successful ECV. Uterine relaxation might not be the strongest effector influencing the success rate of ECV.

After adjustment for potential baseline imbalance, the relative risk increased from 0.73 to 0.85, indicating a smaller magnitude of effect. However, the majority of the confidence intervals still favoured fenoterol.

Comparison with other studies

A Cochrane review on uterine relaxants for ECV concluded that, compared with placebo, beta mimetics were the most effective drugs for increasing cephalic presentation in labour and thereby reducing the caesarean section rate (six studies, 742 participants, relative risk 0.77, 95% confidence interval 0.67 to 0.88).9 Our results indicate that beta mimetics are the most effective in achieving cephalic presentation after ECV. Moreover, fenoterol is much cheaper than atosiban (€0.90 (£0.80; $1.00) versus €31.80 in the Netherlands).

Our study clearly shows that fenoterol has more side effects than atosiban (71% v 5.2%). Discomfort due to palpitations was the most reported side effect, and severe hypotension occurred in one participant after taking fenoterol. Women must be adequately counselled about the side effects in relation to the effectiveness of beta mimetics, as evidence shows that women are willing to undergo treatment if the gain in success outweighs the possible adverse side effects.21 In 2011, one in three deliveries in the US was by caesarean section, making it the most common major surgical procedure for women in the country.22 23 Without clear evidence of an accompanying decrease in maternal and neonatal morbidity or mortality, caesarean delivery might be overused. Therefore, prevention of planned caesarean section is one of the main ways to improve maternal and neonatal outcomes in current obstetric practice.6 24 Breech presentation is the third most common indication for primary caesarean delivery in the US, and ECV is proven to be a safe procedure, so implementation of beta mimetics as the routine uterine relaxants for ECV should be high priorty.25 26 27 28

Conclusion and policy implications

Fenoterol is more effective than atosiban for uterine relaxation before ECV. Fenoterol use is recommended to increase the success rate of ECV and decrease the caesarean delivery rate.

What is already known on this topic

Breech presentation occurs in 3-4% of singleton pregnancies at term, and elective caesarean delivery is the dominant mode of delivery in most countries

External cephalic version (ECV) is a relatively safe obstetrical procedure that reduces the risk of a non-cephalic birth and caesarean delivery

Beta mimetics are widely used to enhance the success rate of ECV, but they have known maternal cardiovascular side effects. Atosiban could be an alternative

What this study adds

Uterine relaxation with fenoterol compared with atosiban results in a higher rate of fetuses in cephalic position after ECV

Cephalic presentation at delivery was not significantly different between groups

The frequency of both poor neonatal and poor maternal outcomes did not differ between groups; emergency delivery occurred twice in the fenoterol group

Side effects occurred more often in the fenoterol group than in the atosiban group

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix: Supplementary material

We thank the research nurses, midwives, and administrative assistants of our consortium; the residents, nurses, midwives, and gynaecologists of the participating centres for their help with participant recruitment and data collection; the members of the data safety monitoring committee, and the women who participated in this study.

Contributors: FV, BO, DP, JB, JvdP, BM, and MK conceived and designed the study. JV, FV, JM, CV, MvP, DP, JB, KV, LvdE, JvdP, BM, and MK acquired the data. JV, FV, and BO carried out the statistical analysis. BM, and MK supervised the study and are the guarantors. BO provided administrative, technical, and material support. All authors analysed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, had full access to all of the data in the study, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This study was supported by the Dutch Obstetric Consortium.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. BM is an advisor for ObsEva, Geneva, Switzerland.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam (reference No MEC 08-364) and by the board of directors of each of the participating hospitals. Participants gave consent was not obtained but the presented data are anonymised and risk of identification is low.

Data sharing: The full dataset is available from the corresponding author at j.velzel@amc.nl on reasonable request.

Transparency: The corresponding author (JV) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported, no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1.Hickok DE, Gordon DC, Milberg JA, Williams MA, Daling JR. The frequency of breech presentation by gestational age at birth: a large population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166:851-2. 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91347-D pmid:1550152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rietberg CCT, Elferink-Stinkens PM, Visser GHA. The effect of the Term Breech Trial on medical intervention behaviour and neonatal outcome in The Netherlands: an analysis of 35,453 term breech infants. BJOG 2005;112:205-9. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00317.x pmid:15663585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet 2000;356:1375-83. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02840-3 pmid:11052579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, Gülmezoglu AM. WHO Working Group on Caesarean Section. WHO statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG 2016;123:667-70. 10.1111/1471-0528.13526. pmid:26681211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibbons L, Belizan JM, Lauer JA, Betran AP, Merialdi M, Althabe F. Inequities in the use of cesarean section deliveries in the world. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:331.e1-19. 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.026 pmid:22464076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American College of Obstatricians and Gynaecologists. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Caughey AB, et al. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:693-711. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000444441.04111.1d pmid:24553167. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;4:CD000083.pmid:25828903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishra M, Sinha P. Does caesarean section provide the best outcome for mother and baby in breech presentation? A perspective from the developing world. J Obstet Gynaecol 2011;31: 495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cluver C, Gyte GML, Sinclair M, Dowswell T, Hofmeyr GJ. Interventions for helping to turn term breech babies to head first presentation when using external cephalic version. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2:CD000184.pmid:25674710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmeyr GJ. Interventions to help external cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;CD000184:CD000184.pmid:14973948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kok M, Bais JM, van Lith JM, et al. Nifedipine as a uterine relaxant for external cephalic version: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:271-6. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817f1f2e pmid:18669722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Obstetrische Werkgroep. Stuitligging.Guidel Dutch Coll Obstet Gynaecol, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lundin S, Broeders A, Melin P. Pharmacokinetic properties of the tocolytic agent [Mpa1, D-Tyr(Et)2, Thr4, Orn8]-oxytocin (antocin) in healthy volunteers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1993;39:369-74. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb02379.x pmid:8222299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akerlund M, Hauksson A, Lundin S, Melin P, Trojnar J. Vasotocin analogues which competitively inhibit vasopressin stimulated uterine activity in healthy women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1986;93:22-7. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1986.tb07807.x pmid:3942702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lippert TH, Peters FD, Kidess E. Dose-response study of fenoterol on uterine activity in labor at term. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1980;11:219-24. 10.1159/000299840 pmid:7450566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasmussen BB, Larsen LS, Senderovitz T. Pharmacokinetic interaction studies of atosiban with labetalol or betamethasone in healthy female volunteers. BJOG 2005;112:1492-9. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00735.x pmid:16225568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinheimer TM, Bee WH, Resendez JC, Meyer JK, Haluska GJ, Chellman GJ. Barusiban, a new highly potent and long-acting oxytocin antagonist: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic comparison with atosiban in a cynomolgus monkey model of preterm labor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:2275-81. 10.1210/jc.2004-2120 pmid:15671092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beuckens A, Rijnders M, Verburgt-Doeleman GH, Rijninks-van Driel GC, Thorpe J, Hutton EK. An observational study of the success and complications of 2546 external cephalic versions in low-risk pregnant women performed by trained midwives. BJOG 2016;123:415-23. 10.1111/1471-0528.13234. pmid:25639281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins S, Ellaway P, Harrington D, Pandit M, Impey LWM. The complications of external cephalic version: results from 805 consecutive attempts. BJOG 2007;114:636-8. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01271.x pmid:17355270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vlemmix F, Rosman AN, Rijnders ME, et al. Implementation of client versus care-provider strategies to improve external cephalic version rates: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015;94:518-26. 10.1111/aogs.12609 pmid:25682778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vlemmix F, Kuitert M, Bais J, et al. Patient’s willingness to opt for external cephalic version. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2013;34:15-21. 10.3109/0167482X.2012.760540 pmid:23394409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton BE, Hoyert DL, Martin JA, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2010-2011. Pediatrics 2013;131:548-58. 10.1542/peds.2012-3769 pmid:23400611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacDorman M, Declercq E, Menacker F. Recent trends and patterns in cesarean and vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) deliveries in the United States. Clin Perinatol 2011;38:179-92. 10.1016/j.clp.2011.03.007 pmid:21645788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregory KD, Jackson S, Korst L, Fridman M. Cesarean versus vaginal delivery: whose risks? Whose benefits?Am J Perinatol 2012;29:7-18. 10.1055/s-0031-1285829 pmid:21833896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion no 340. Mode of term singleton breech delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:235-7. 10.1097/00006250-200607000-00058 pmid:16816088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barber EL, Lundsberg LS, Belanger K, Pettker CM, Funai EF, Illuzzi JL. Indications contributing to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118: 29-38. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821e5f65 pmid:21646928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collaris RJ, Oei SG. External cephalic version: a safe procedure? A systematic review of version-related risks. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2004;83:511-8. 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00347.x pmid:15144330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grootscholten K, Kok M, Oei SG, Mol BWJ, van der Post JA. External cephalic version-related risks: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:1143-51. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818b4ade pmid:18978117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix: Supplementary material