INTRODUCTION

For nearly 50 years, the Common Rule has required Institutional Review Board (IRB) oversight of federally‐funded research to protect the rights and welfare of human research participants. Over time, research has changed and research studies often involve multiple sites. Recognizing that research policies must evolve with science and ensure both efficiency and protections for research participants, NIH released a Policy on the Use of a Single Institutional Review Board for Multi‐Site Research in June 2016.1

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The concept of using a single Institutional Review Board (IRB) to oversee multisite clinical research studies is not new. In 2004, the Secretary's Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP) noted that single IRBs were used infrequently and suggested that a workshop be convened to examine the challenges associated with using alternatives to local IRB review. The workshop took place in 2005, and was sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the HHS Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP).2 A number of the models considered at the workshop involved single or central IRBs.

This led, a year later, to a National Conference on Alternative IRB Models, which was sponsored by the leaders of the previous workshop, as well as other federal agencies, and a number of organizations representing research institutions, research administrators, and disciplinary societies. This second meeting underscored that local IRB review for multisite trials was duplicative and time‐consuming. Speakers described institutional support for the use of central IRBs and concluded that, although use of alternative models for IRB review was increasing, there was a need for additional encouragement from sponsors and regulatory agencies. Later, in 2009, the Office for Human Research Protection (OHRP) issued a Federal Register Notice asking whether OHRP should pursue a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) to enable OHRP to hold IRBs and the institutions or organizations operating the IRBs directly accountable for meeting certain regulatory requirements of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regulations for the protection of human subjects.3 OHRP was contemplating this regulatory change to encourage institutions to rely on IRBs that are operated by another institution or organization, when appropriate.

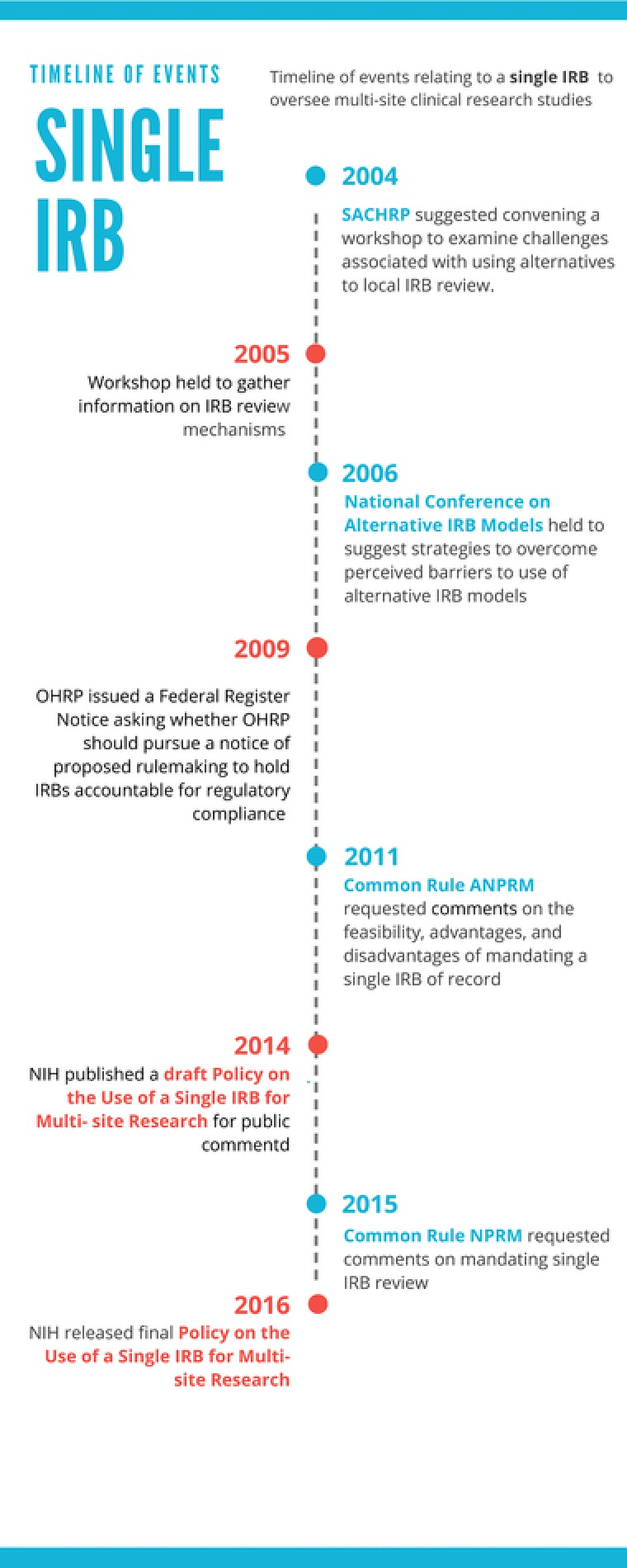

In 2009, work began to develop an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) to revise and update the Common Rule (45 CFR part 46).4 The ANPRM, which was published in 2011, included a request for comment on the feasibility, advantages and disadvantages of mandating a single IRB of record for all studies subject to the Common Rule, which were conducted in US institutions and involved more than one site. In 2014, the NIH published a draft Policy on the Use of a Single IRB for Multisite Research for public comment. The ANPRM proposed mandate, which is consistent with the final NIH policy's expectation, was also proposed in the 2015 Common Rule Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (Figure 1).5

Figure 1.

Timeline of events relating to a single IRB to oversee multisite clinical research studies.

As these policy developments unfolded, there was a rising call to reduce the burden and improve the process for review of multisite clinical research studies. Support for the use of single IRBs was included in the 2011 Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues report, “Moral Science: Protecting Participants in Human Subjects Research.”6 The Commission recommended reducing “unnecessary, duplicative, or redundant institutional review board review in multisite studies,” and stated that “The use of a single institutional review board of record should be made the regulatory default unless institutions or investigators have sufficient justification to act otherwise.” Further support was provided in the 2014 National Science Foundation's report on “Reducing Investigators’ Administrative Workload for Federally Funded Research,”7 which recommended that regulators support the use of single IRBs for multisite research and decreased institutional liability, as part of regulatory reforms designed to reduce administrative burdens. Most recently, the National Academy of Science's 2016 report on “Optimizing the Nation's Investment in Academic Research: A New Regulatory Framework for the 21st Century”8 echoed prior calls for a regulatory mandate for single IRB review for domestic sites, with an allowance for exceptions for sites that have particular needs (e.g., Tribal sovereignty concerns).

The proposal for using a single IRB in the Common Rule ANPRM, the NIH draft Policy on the Use of a Single IRB for Multisite Research, and the Common Rule NPRM received mostly positive comments from the public. For the NIH draft policy, researchers, scientific and professional societies, and patient advocacy organizations supported the use of a single IRB for multisite studies involving the same protocol. Commenters stated that the policy would help streamline IRB review and would not undermine and might even enhance protections for research participants. Most of the comments also favored the approach the NIH proposed to promote the use of single IRBs by making reliance on a single IRB an expectation for all nonexempt multisite studies carried out at US sites. Academic institutions and organizations representing them were more critical, and generally disagreed with the scope of the proposed policy, while suggesting that NIH provide incentives for institutions to rely on a single IRB. In drafting the final policy, the NIH took all comments into consideration.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NIH POLICY

The Final NIH policy on the Use of a Single Institutional Review Board for Multisite Research is designed to promote and advance this paradigm shift for IRB review. We incorporated a delay in its implementation to allow the research community time to work out how they will adjust their administrative processes. The policy will apply to grant applications received on or after 25 May 2017, contract solicitation issued on or after 25 May 2017, and NIH intramural research protocols submitted for initial review after 25 May 2017. The policy covers domestic sites where each site will conduct the same nonexempt human subjects research study.

We expect that any challenges associated with implementation of the policy will be short‐lived. Once the conversion to newer processes are made, including changes to institutional policies and procedures, the benefits of widespread use of single IRBs are anticipated to outweigh any burdens to investigators and research institutions resulting from changes to established practices. To facilitate a smooth transition, the NIH and others are developing resources for institutions and investigators. In addition, the SACHRP is working on a series of Points to Consider that should be extremely helpful to the research community.

Because a number of public commenters on the draft NIH policy requested specific guidance on how to budget for single IRBs within grant applications and contract proposals, the NIH published Guidance on how costs associated with single IRBs may be charged as direct vs. indirect costs in a series of case studies (NOT‐OD‐16‐109).

One important initiative designed to help research institutions to rely on external IRBs is the Streamlined, Multisite, Accelerated Resources for Trials (SMART) IRB Reliance Platform, a resource developed by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).9 The platform provides a master Reliance (Authorization) Agreement that can be used to formalize agreements to use or serve as a central IRB for many studies, or a single IRB for one or more multisite study, and guidance documents for implementing a single IRB for multisite research. These documents have been developed with the critical assistance of NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) recipients who are recognized for their expertise on IRBs and IRB processes. In addition, NCATS is funding Recruitment Innovations Center and Trial Innovations Centers to address and overcome challenges for multisite research and to foster innovation.

Prior to the implementation date of the policy, the NIH expects to release a series of Frequently Asked Questions, decisions trees, and guidance. It is important to note that the policy excludes some types of institutions, NIH awards, and specific populations. Foreign sites, career development, institutional training, and fellowship awards and populations for which there are federal, state, or tribal requirements for local review are not subject to the policy. Tribal regulations and policy are mentioned specifically in order to ensure that their importance is recognized and respected. The policy states that other exceptions may be requested when there is a compelling justification. Such determinations will be posted publicly, would be granted by NIH staff, and would not require additional adjudication.

Increasingly, single IRBs are being used and developed to review multisite research. Although we and many others are convinced that their use will be the norm in a few years, and any temporary discomforts related to the transition will be a dim memory, NIH commits to monitoring the impact of the policy on research. Over time, we anticipate seeing benefits for research, such as more efficient initiation of multisite studies, maintaining high standards for protection of human research participants, and reduction of administrative burden.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Final NIH Policy on the Use of a Single Institutional Review Board for Multi‐Site Research. Notice Number: NOT‐OD‐16‐094. The National Institutes of Health. June 21, 2016. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice‐files/NOT‐OD‐16‐094.html

- 2. Alternative Models of IRB Review Workshop Summary Report . National Institutes of Health, Office for Human Research Protections, Association of American Medical Colleges, and American Society of Clinical Oncology. Washington, D.C. November 17–18, 2005. https://archive.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp/documents/AltModIRB.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3. Request for Information and Comments on IRB Accountability . Office for Human Research Protections. March 5, 2009. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/newsroom/rfc/com030509.html

- 4. Human Subjects Research Protections: Enhancing Protections for Research Subjects and Reducing Burden, Delay, and Ambiguity for Investigators. Federal Register. Advance notice of proposed rulemaking. Volume 76, Number. 143. July 26, 2011. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR‐2011‐07‐26/html/2011‐18792.htm [Google Scholar]

- 5. Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects. Federal Register. Notice of proposed rulemaking. Volume 80, Number.173. September 8, 2015. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR‐2015‐09‐08/pdf/2015‐‐21756.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moral Science . Protecting Participants in Human Subjects Research. Report by the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. December 2011. https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu/pcsbi/sites/default/files/Moral%20Science%20June%202012.pdf

- 7. Reducing Investigators' Administrative Workload for Federally Funded Research. Report by the National Science Board. NSB‐14‐18. March 10, 2014. https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2014/nsb1418/nsb1418.pdf

- 8. Optimizing the Nation's Investment in Academic Research: A New Regulatory Framework for the 21st Century. Chapter 5: Regulations and Policies Related to the Conduct of Research. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/21824. 2016. https://www.nap.edu/read/21824/chapter/7 [PubMed]

- 9. NCATS Streamlined , Multisite, Accelerated Resources for Trials (SMART) IRB Reliance Platform. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). October 14, 2016. (Retrieved from: https://ncats.nih.gov/expertise/clinical/smartirb)