Abstract

The filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans primarily reproduces by forming asexual spores called conidia, the integrity of which is governed by the NF-κB type velvet regulators VosA and VelB. The VosA-VelB hetero-complex regulates the expression of spore-specific structural and regulatory genes during conidiogenesis. Here, we characterize one of the VosA/VelB-activated developmental genes, called vadA, the expression of which in conidia requires activity of both VosA and VelB. VadA (AN5709) is predicted to be a 532-amino acid length fungal-specific protein with a highly conserved domain of unknown function (DUF) at the N-terminus. This DUF was found to be conserved in many Ascomycota and some Glomeromycota species, suggesting a potential evolutionarily conserved function of this domain in fungi. Deletion studies of vadA indicate that VadA is required for proper downregulation of brlA, fksA, and rodA, and for proper expression of tpsA and orlA during sporogenesis. Moreover, vadA null mutant conidia exhibit decreased trehalose content, but increased β(1,3)-glucan levels, lower viability, and reduced tolerance to oxidative stress. We further demonstrate that the vadA null mutant shows increased production of the mycotoxin sterigmatocystin. In summary, VadA is a dual-function novel regulator that controls development and secondary metabolism, and participates in bridging differentiation and viability of newly formed conidia in A. nidulans.

Introduction

Species of the genus Aspergillus are widespread in nature and have both beneficial and detrimental effects on humankind [1–3]. This genus includes plant and human pathogenic fungi, such as Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus, and other species that are of tremendous importance to the industrial production of enzymes, organic acids, and foods [1, 4]. Aspergillus nidulans is a model ascomycetous fungus for studying fungal development and secondary metabolism [5, 6]. All Aspergillus species produce asexual spores called conidia, which are the main reproductive propagule and the infectious particles [7]. Conidia are formed on a multicellular asexual structure called the conidiophore [8, 9]. Conidiophore formation is an elaborate process requiring differentiation of multiple cell types and precise regulation of several hundred genes [10, 11]. The mechanisms regulating asexual development (conidiation) have been well studied in A. nidulans [5, 6, 10].

In A. nidulans, the process of conidiation is regulated mainly by the three central regulatory genes, brlA, abaA, and wetA [10, 12, 13]. They control expression of conidiation-specific genes and determine the order of activation of downstream genes [12–15]. BrlA is a key element for initiation of conidiation and activates abaA, which in turn activates wetA [16–19]. WetA regulates spore-specific genes’ expression and plays a crucial role in the synthesis of spore wall components during the late phase of conidiation [20, 21]. Our previous genetic studies identified the velvet regulator VosA that plays a role in negative feedback regulation of brlA during the late phase of conidiation and in conidia [22]. In addition, VosA and VelB, together with WetA, regulate conidial maturation and trehalose biosynthesis [22–24].

The velvet regulators, including VosA, VeA, VelB, and VelC, are highly conserved in filamentous and dimorphic fungi and play a pivotal role in fungal biology [22, 25, 26]. In Aspergillus species, the velvet proteins coordinate fungal growth, development, pigmentation, and primary/secondary metabolism [22–24, 27–33]. These regulators form various homo- or hetero-complexes, such as VelB-VeA-LaeA, VosA-VelB, VosA-VelC, and VelB-VelB, controlling asexual sporogenesis, sexual fruiting, sterigmatocystin (ST) production, and spore maturation [23, 24, 27, 28]. Among these complexes, the VosA-VelB complex functions as a key functional unit controlling spore maturation, trehalose biosynthesis, and conidial germination [23, 24]. Recent studies have demonstrated that the velvet proteins are fungus-specific transcription factors that recognize the specific cis-acting responsive elements present in the promoters of direct target genes [34, 35]. The VosA-VelB heterodimer represses developmental regulatory genes but activates genes associated with spore maturation and trehalose biosynthesis in conidia [35]. Several predicted target genes that are directly regulated by the VosA-VelB heterodimer have been proposed [35]. Importantly, the VosA-VelB complex directly represses β (1,3)-glucan biosynthesis in asexual and sexual spores [36].

In this study, we characterize one activatory target gene, called vadA (VosA/VelB-Activated Developmental gene; AN5709). Levels of vadA mRNA in conidia are reduced by the deletion of vosA or velB. The vadA gene appears to be specifically expressed during the late phase of conidiation and in conidia. The deletion of vadA results in the enhanced production of sexual fruiting bodies (cleistothecia) and altered expression of brlA, vosA, and velB. The ΔvadA conidia exhibit reduced trehalose levels, lowered viability, and increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. In addition, the deletion of vadA causes increased β(1,3)-glucan accumulation in asexual spores. Genetic studies demonstrated that VadA is required for proper regulation of brlA, fksA (1,3-beta-glucan synthase), rodA (hydrophobins), tpsA (trehalose-6-phosphate synthase), and orlA (trehalose 6-phosphate phosphatase) in asexual spores. Overexpression (OE) of vadA causes enhanced formation of asexual spores. We further demonstrated that ΔvadA strains showed increased ST production. Overall, these results suggest that VadA is a multifunctional sporogenesis regulator controlled by the VosA-VelB complex in A. nidulans.

Materials and methods

Strains, media, and culture conditions

Fungal strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All media used in this study have been previously described [28, 37]. Briefly, liquid or solid minimal media with 1% glucose (MMG) were used for general purposes and sexual medium (SM) was used for enhancing sexual development. To examine the effects of overexpression of vadA under the alcA promoter [38, 39], tested strains were inoculated on MMG or MM with 100 mM threonine as the sole carbon source (MMT). All strains were grown on solid or liquid media with appropriate supplements at 37°C. To check the number of conidia and cleistothecia, wild-type (WT), mutants, and complemented strains were point inoculated and cultured on solid MM or SM for four or seven days at 37°C. Escherichia coli DH5α cells were grown in Luria–Bertani medium with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) for plasmid amplification.

Table 1. Aspergillus strains used in this study.

| Strain name |

Relevant genotype | References |

|---|---|---|

| FGSC4 | A. nidulans wild type, veA+ | FGSCa |

| RJMP1.59 | pyrG89; pyroA4; veA+ | [40] |

| TNJ36 | pyrG89; AfupyrG+; pyroA4; veA+ | [41] |

| THS15.1 | pyrG89; pyroA4; ΔvosA::AfupyrG+; veA+ | [23] |

| THS16.1 | pyrG89; pyroA4; ΔvelB::AfupyrG+; veA+ | [23] |

| THS30.1 | pyrG89; AfupyrG+; veA+ | [36] |

| THS33.1~3 | pyrG89; pyroA4; ΔvadA::AfupyrG+; veA+ | This study |

| THS34.1 | pyrG89; pyroA::vadA(p)::vadA::FLAG3x::pyroAb; ΔvadA::AfupyrG+; veA+ | This study |

| THS40.1 | pyrG89; AfupyrG+; pyroA::alc(p)::vadA::FLAG::pyroAb; veA+ | This study |

a Fungal Genetic Stock Center

b The 3/4 pyroA marker causes targeted integration at the pyroA locus.

For Northern blot analysis, samples were collected as previously described [28]. Briefly, for conidia, the conidia of WT and mutant strains were spread onto solid media and incubated at 37°C. After two days of culture, the conidia were filtered, collected, and stored at −80°C. For hyphal samples, conidia of WT and mutant strains were inoculated into 200 mL liquid MM in 1 L flasks and incubated at 37°C. Samples of the submerged cultures were collected at designated time points and stored at -80°C. For developmental induction, the conidia of WT and mutant strains were inoculated into liquid MM and incubated for 18 h. Mycelia were filtered, washed, and spread in a monolayer on solid MM, and the plates were air exposed for asexual developmental induction, or sealed of air and blocked from light for sexual developmental induction.

Construction of the vadA mutants

The oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 2. The vadA deletion (ΔvadA) mutant strain was generated by double-joint PCR (DJ-PCR) as previously described [42]. The flanking regions of the vadA gene were amplified using the primer pairs OHS859/OHS861 and OHS860/OHS862 from A. nidulans FGSC4 genomic DNA as a template. The A. fumigatus pyrG marker was amplified from A. fumigatus AF293 genomic DNA with the primer pair OJH84/OJH85. The vadA deletion cassette was amplified with primer pair OHS863/OHS864 and was introduced into a RJMP1.59 [40] protoplasts generated by the Vinoflow FCE lysing enzyme (Novozymes) [43]. To complement ΔvadA, the WT vadA gene region, including its predicted promoter, was amplified with the primer pair OHS888/OHS889, digested with EcoRI and NotI, and cloned into pHS13 [23]. The resulting plasmid pHSN85 was then introduced into the recipient ΔvadA strain THS33.1 to give rise to THS34.1. To generate the alcA(p)::vadA fusion construct, the vadA ORF derived from genomic DNA was amplified using the primer pair OHS887/OHS889. The PCR product was then double digested with EcoRI and NotI and cloned into pHS82 [23]. The resulting plasmid pHS82 was then introduced into RJMP1.59. The vadA-overexpressing strains among the transformants were screened by Northern blot analysis using a vadA ORF probe followed by PCR confirmation.

Table 2. Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Name | Sequence (5′ → 3′)a | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| OHS753 | ATGTCTCCCAGACCACCAAGTATC | 5′ vadA probe |

| OHS754 | GGCTTGAGCTTGGATATGAACCG | 3′ vadA probe |

| OHS859 | GTGGTTGCTAGTCCGCAGAGAG | 5′ flanking region of vadA |

| OHS860 | GCTGGGTCAAACAAGCCAGTGC | 3′ flanking region of vadA |

| OHS861 | GGCTTTGGCCTGTATCATGACTTCA GGAGGCCGTAGTAGAGTGAAAGATG | 5′ vadA with AfupyrG tail |

| OHS862 | TTTGGTGACGACAATACCTCCCGAC CGACGAGCTGTATGCCTTCATG | 3′ vadA with AfupyrG tail |

| OHS863 | CTGGGTGGAGAGGCTAACTGC | 5′ nested of vadA |

| OHS864 | ACTCCAGCGCATTATCCAACTCAG | 3′ nested of vadA |

| OHS887 | ATATGAATTCATGTCTCCCAGACCACCAAGTATC | 5′ vadA with EcoRI |

| OHS888 | ATATGAATTCTGCTCCTGGTAAGAAATGCTCG | 5′ vadA with pro and EcoRI |

| OHS889 | ATATGCGGCCGCCAAGTTAGTGATGTACTCTTTCATATCC | 3′ vadA with NotI |

| OJH84 | GCTGAAGTCATGATACAGGCCAAA | 5′ AfupyrG marker |

| OJH85 | ATCGTCGGGAGGTATTGTCGTCAC | 3′ AfupyrG marker |

| OJA142 | CTGGCAGGTGAACAAGTC | 5′ brlA probe |

| OJA143 | AGAAGTTAACACCGTAGA | 3′ brlA probe |

| OJA150 | CAGTACGTCAATATGGAC | 5′ wetA probe |

| OJA151 | GTGAAGTTGACAAACGAC | 3′ wetA probe |

| OJA156 | ATGCTATATTCACCACCT | 5′ rodA probe |

| OJA157 | TGACCTACCAGAATATCG | 3′ rodA probe |

| OMN66 | TTTCCAGATCCTTCGCAG | 5′ vosA probe |

| OMN63 | ATAGAAACAGCCACCCAG | 3′ vosA probe |

| OMN125 | TATGCACTGGCACTCAAGCAACCG | 5′ velB probe |

| OMN126 | GTGCATGACGGTCGTATCTGGTCC | 3′ velB probe |

| OMN143 | ACTTATGCCAACGTTCTGCG | 5′ fksA probe |

| OMN144 | AAAGAGCGGGCAGCATAATG | 3′ fksA probe |

| OMN176 | CCATCACCATAAAGCGATCAG | 5′ tpsA probe |

| OMN177 | CAGTTTCGAGAAGTTAAGCGC | 3′ tpsA probe |

| OMN182 | CAGCCGCATCTCCAACTTAG | 5′ orlA probe |

| OMN183 | TGTTAGCAGCAATTCATGGCG | 3′ orlA probe |

a Tail sequences are shown in italics. Restriction enzyme sites are in bold.

Nucleic acid isolation and manipulation

Total RNA isolation and Northern blot analyses were performed as previously described [42, 44]. The DNA probes for Northern blot analysis were amplified using the appropriate oligonucleotide pairs (Table 2) from the coding regions of individual genes using FGSC4 genomic DNA as a template. 32P-labeled probes were prepared using the Random Primer DNA Labeling Kit (Clontech) with [α-32P]-dCTP. Genomic DNA extractions were carried out as previously described [43].

Spore viability test

To check spore viability, fresh conidia from two-day-old cultured WT and mutant strains were spread on solid MM and incubated at 37°C. Conidia from five- and ten-day-old cultures were then collected. About 100 conidia were inoculated onto solid MM and incubated at 37°C for 48 h in triplicate. Survival rates were calculated as the ratio of the number of viable colonies to the number of spores inoculated.

Spore trehalose assay

The spore trehalose assay was performed as previously described [22]. Briefly, conidia from two-day-old cultured WT and mutant strains were collected, washed with ddH2O, resuspended in 200 μL of ddH2O, and incubated at 95°C for 20 min. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation, mixed with an equal volume of 0.2 M sodium citrate (pH 5.5), and incubated at 37°C for 8 h with or without (as a control) 3 mU of trehalase (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). The amount of glucose generated from the trehalose was assayed with a Glucose Assay Kit (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) in triplicate.

Oxidative stress tolerance test

The hydrogen peroxide sensitivity of conidia was tested by spotting 10 μL of serially diluted conidia (10 to 105) on solid MM with 0 and 2.5 mM of H2O2 and incubating at 37°C for 48 h.

β(1,3)-glucan analysis

The β(1,3)-glucan assay was performed as previously described [36]. Briefly, two-day old conidia of WT and mutants were collected in ddH2O. Conidia suspensions (102 to 105) were resuspended in 25 μL of ddH2O and were mixed with Glucatell® reagents (Associates of Cape Cod, East Falmouth, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After incubation, diazo reagents were added to stop the reaction. The optical density at 540 nm was determined. This test was performed in triplicate.

Sterigmatocystin (ST) extraction and HPLC conditions

Briefly, 106 conidia of each strain were inoculated into 2 mL liquid complete medium (CM) and cultured at 30°C for 7 days. Secondary metabolites were extracted by adding 2 mL of CHCl3, the organic (CHCl3) phase separated by centrifugation and transferred to new glass vials, evaporated in the fume hood, and resuspended in 1 mL HPLC-grade acetonitrile:methanol (50:50, v/v). The samples were filtered through a 0.45-μm pore filter.

High-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection (HPLC-DAD) analysis was performed with a Series 1100 binary pump with an auto sampler and Nova-Pak C-18 column (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). Ten microliters of the samples were injected in to the column. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile:water (60:40, v/v). The flow rate was 0.8 mL/min. The ST stock solution (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in acetonitrile:methanol (50:50, v/v). A linear calibration curve (R2 = 0.998) was constructed with a ST dilution series of 10, 1, 0.5, 0.1, and 0.005 μg/mL. ST was detected at a wavelength of 246 nm. The retention time for ST was approximately 5.6 min.

Microscopy

The colony pictures were taken using Sony digital (DSC-F828) camera. Micrographs were taken using a Zeiss M2Bio microscope equipped with AxioCam and AxioVision digital imaging software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between WT and mutant strains were evaluated by Student’s unpaired t-test. Mean ± SD are shown. P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Expression and phylogenetic analyses of vadA

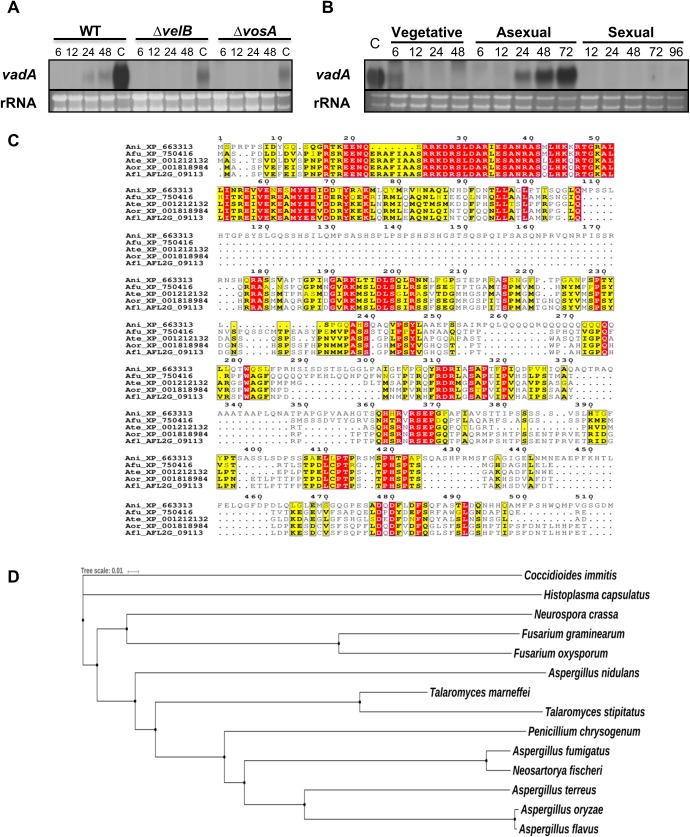

Our previous data showed that the accumulation of vadA mRNA in conidia is dependent on both VosA and VelB [35]. To further verify the vadA expression during asexual development, we examined the levels of vadA mRNA in WT, ΔvosA, and ΔvelB strains under asexual developmental conditions. While accumulation of vadA mRNA was detectable at 24 h after developmental induction and was high in the WT conidia, vadA mRNA was decreased in both the ΔvosA and ΔvelB strains compared to WT (Fig 1A). We also examined levels of the vadA transcript throughout the life cycle and found that the levels of the vadA transcript were high during the late phase of asexual development (Fig 1B). These results suggest that vadA is specifically expressed during conidiogenesis, and its expression is largely dependent on both VelB and VosA. Multiple sequence alignment of Aspergillus spp. suggests that the predicted VadA protein contains a highly conserved domain of unknown function (DUF) at the N-terminus (Fig 1C). VadA orthologues are found in many Ascomycota (Neurospora, Sordaria, and Marssonina) and some Glomeromycota (Rhizophagus), implying that this DUF might be ancient, and has uniquely evolved in fungi, but not plants and animals (Fig 1D).

Fig 1. Summary of vadA.

(A) Northern blot showing levels of vadA mRNA in WT (FGSC4), ΔvosA (THS15.1), and ΔvelB (THS16.1) strains. Conidia (asexual spores) are indicated as C. The time (hours) of incubation in post asexual developmental induction is shown. Equal loading of total RNA was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA. (B) Levels of vadA mRNA during the lifecycle of A. nidulans WT (FGSC4). Conidia (asexual spores) are indicated as C. Time (h) of incubation in liquid submerged culture and post-asexual or sexual developmental induction is shown. Equal loading of total RNA was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA. (C) Alignment of A. nidulans VadA (Ani: XP_663313), A. fumigatus VadA (Afu: XP_750416), A. terreus VadA (Ate: XP_001212132), and A. oryzae VadA (Aor: XP_001818984) with VadA of A. flavus (Afl: AFL2G_09113). ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) and ESPript (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript/ [45]) were used for the alignment and presentation. (D) A phylogenetic tree of VadA-like proteins identified in various fungal species including A. nidulans FGSC4 (XP_663313), A. terreus NIH2624 (XP_001212132), A. oryzae RIB40 (XP_001818984), A. fumigatus Af293 (XP_750416), A. flavus AFL3357 (AFL2G_09113), Talaromyces marneffei ATCC18224 (XP_002144293), T. stipitatus ATCC10500 (XP_002341254), Penicillium chrysogenum Wisconsin 54–1225 (XP_002562176), Neosartorya fischeri NRRL181 (XP_001264997), Neurospora crassa OR74A (XP_959987), Coccidioides immitis RS (XP_001244564), Histoplasma capsulatus G186AR (EEH08887), Fusarium graminearum PH1 (XP_011326731), and F. oxysporum Fo47(EWZ44948). A phylogenetic tree of putative VadA orthologues was generated by MEGA 5 software (http://www.megasoftware.net/) using the alignment data from ClustalW2. The tree results were submitted to iTOL (http://itol.embl.de/) to generate the figure.

VadA balances development

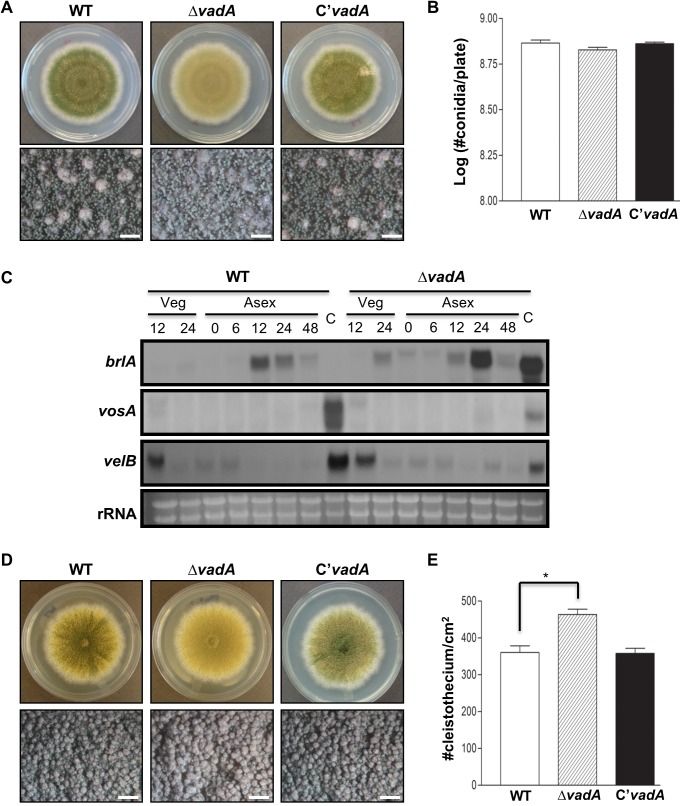

To study functions of vadA, we generated the vadA deletion (ΔvadA) mutant, complemented strains (C’), and examined their phenotypes. The ΔvadA mutant produced light green conidia distinct from those of WT and C’ strains (Fig 2A). The ΔvadA mutant produced a similar number of conidia as WT and C’ strains (Fig 2B). We then checked whether the absence of vadA altered the patterns of brlA, vosA, and velB mRNA accumulation during vegetative growth and asexual development. As shown Fig 2C, brlA mRNA accumulation in the ΔvadA mutant was detectable in vegetative growth, early asexual development (~6 h), and conidia, but was not observed in WT cells. The levels of vosA and velB mRNAs in the ΔvadA mutant were decreased compared to that of WT. These results indicate that VadA is required for full conidial pigmentation and proper expression of asexual developmental genes.

Fig 2. Developmental phenotypes of the ΔvadA mutant.

(A) Colony photographs of WT (FGSC4), ΔvadA (THS33.1), and the complemented (THS34.1) strains point inoculated on solid MM and grown for four days (top and bottom panels). The bottom panel shows close-up views of the center of the plates. (bar = 0.5 mm) (B) Quantitative analysis of conidiospore formation of the strains shown in (A). (C) Northern blot for brlA, vosA, and velB mRNAs in WT (FGSC4) and ΔvadA (THS33.1) strains in vegetative growth (Veg) and post-asexual developmental induction (Asex). Numbers indicate the time (h) of incubation after induction of asexual development. Equal loading of total RNA was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA. (D) Colony photographs of WT (FGSC4), ΔvadA (THS33.1), and the complemented (THS34.1) strains point inoculated on solid SM and grown for five days (top and bottom panels). The bottom panel shows close-up views of the center of the plates. (bar = 0.5 mm) (E) Quantitative analysis of cleistothecia formation of strains shown in (A) (* P < 0.05).

To test whether VadA is also associated with sexual development, WT, ΔvadA, and the complemented strains were inoculated on SM, and the numbers of sexual fruiting bodies were counted. As shown Fig 2D and 2E, the ΔvadA mutant produced significantly higher numbers of sexual fruiting bodies compared to the WT and complemented strains, suggesting that VadA is also required for proper sexual development in A. nidulans.

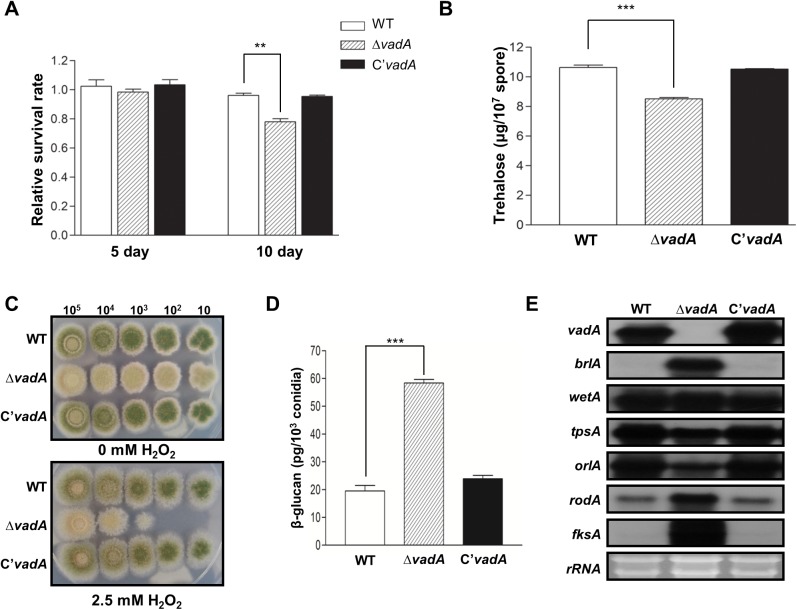

VadA governs the conidial integrity

As described above, vadA is a conidia-specific gene (Fig 1) and is required for proper expression of brlA, vosA, and velB in conidia (Fig 2), implying that VadA has a potential role in conidiogenesis. To test this idea, the conidial viability, trehalose content, oxidative stress tolerance, β-glucan level, and expression of genes associated with conidiogenesis were compared between WT, ΔvadA, and C’ strains (Fig 3). When we checked the viability of conidia of colonies grown for five and ten days, the ΔvadA mutant conidia had a slight loss of viability at ten days (Fig 3A). We measured trehalose in two-day conidia of WT, ΔvadA, and C’ strains, and showed that the trehalose content in the ΔvadA mutant conidia was significantly decreased compared to that in the WT and complemented strains (Fig 3B). As trehalose acts as a protectant against several stresses, we examined the conidial tolerance of the strains to oxidative stress. As shown in Fig 3C, the ΔvadA mutant conidia were more sensitive to oxidative stress than WT and C’ conidia. We also checked β(1,3)-glucan levels and found that its levels in the ΔvadA conidia were higher than that of WT and C’ conidia (Fig 3D).

Fig 3. The role of vadA in conidia.

(A) Viability of the conidia of WT (FGSC4), ΔvadA (THS33.1), and C’ (THS34.1) strains grown at 37°C for 5 and 10 days (** P < 0.01). (B) Amount of trehalose per 107 conidia in the two-day-old conidia of WT (FGSC4), ΔvadA (THS33.1), and C’ (THS34.1) strains (measured in triplicate) (*** P < 0.001). (C) Tolerance of the conidia of WT (FGSC4), ΔvadA (THS33.1), and C’ (THS34.1) strains to H2O2 treatment. (D) Amount of β-glucan (pg) per 103 conidia in the two-day-old conidia of WT (FGSC4), ΔvadA (THS33.1), and C’ (THS34.1) strains (measured in triplicate). (E) Levels of vadA, brlA, wetA, tpsA, orlA, rodA, and fksA transcripts in the conidia of WT (FGSC4), ΔvadA (THS33.1), and C’ (THS34.1) strains. Equal loading of total RNA was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining of rRNA.

To correlate phenotypic changes caused by the deletion of vadA with molecular events, we examined mRNA levels of brlA, wetA, tpsA, orlA, rodA, and fksA in conidia. The ΔvadA mutant conidia showed decreased mRNA levels of tpsA and orlA, which are associated with trehalose biosynthesis, and increased transcript levels of brlA, rodA, and fksA, suggesting that VadA is required for properly controlling expression of certain spore-metabolic and developmental regulatory genes in conidia (Fig 3E). Taken together, VadA is expressed during conidiogenesis and globally affects metabolism, spore wall structure, and feed-back control thereby exerting the integrity of conidia.

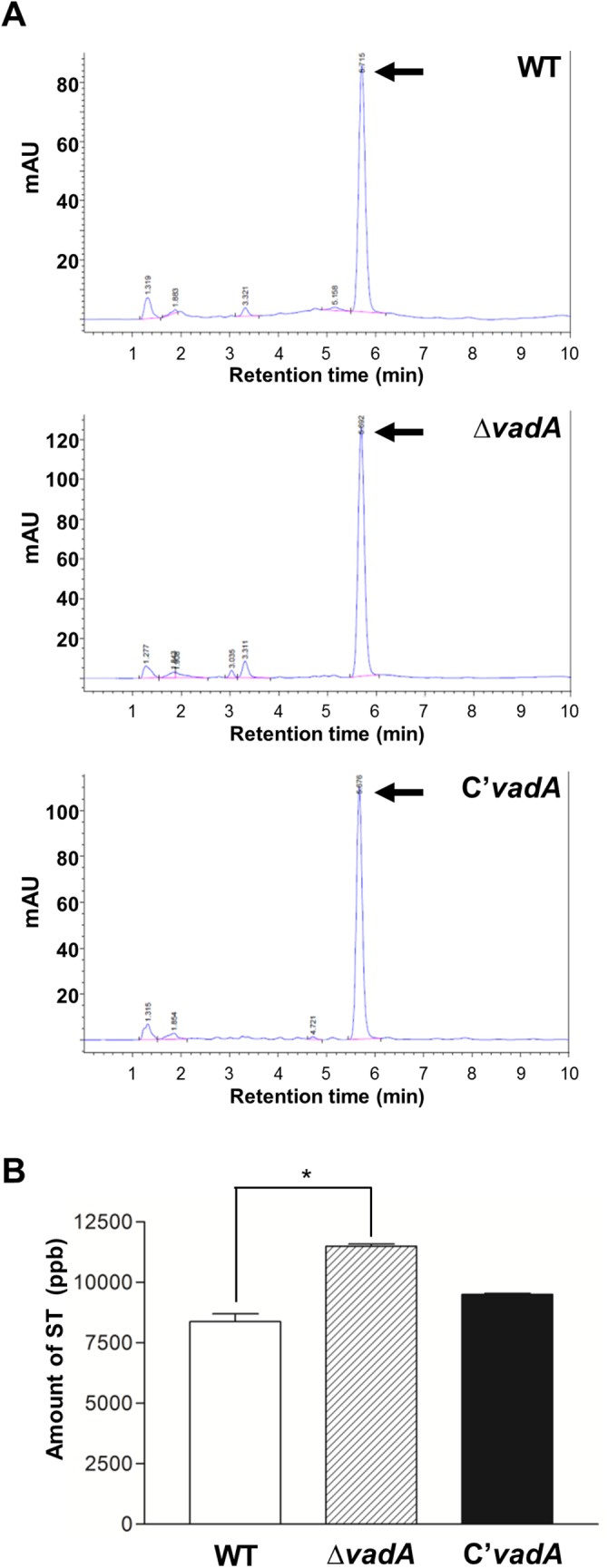

The absence of vadA leads to elevated ST production

We then tested whether the absence of vadA would affect the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in A. nidulans. TLC image showed that all ΔvadA mutant strains produced increased amounts of ST compared to WT (S1 Fig). To further examine this result, we extracted ST in WT, ΔvadA, and C’ strains and analyzed these sample using HPLC. As shown Fig 4, the ΔvadA mutant produced increased amounts of ST compared to WT and C’ strains, suggesting that VadA may repress ST production in A. nidulans (Fig 4). Overall, these results imply that VadA functions controlling development, spore primary metabolism, and hyphal secondary metabolism.

Fig 4. ST analysis.

(A) Determination of ST production by WT (FGSC4) (Top), ΔvadA (THS33.1) (Middle), and C’ (THS34.1) (Bottom) strains. The culture supernatant of each strain was extracted with chloroform and subjected to HPLC. Arrows indicate ST. (B) Amount of ST produced after seven days of stationary culture (CM) of WT (FGSC4), ΔvadA (THS33.1) and C’ (THS34.1) strains (measured in duplicate).

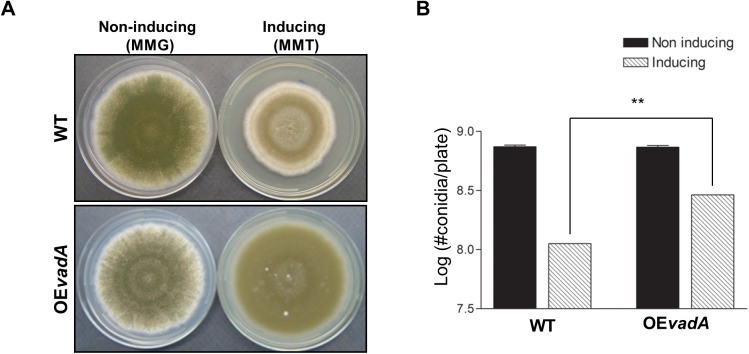

Overexpression of vadA leads to enhanced conidiation

As mentioned above, the absence of vadA caused enhanced production of cleistothecia and altered brlA expression. To further test the sufficiency of VadA influencing fungal development, we constructed the vadA overexpression (OE) mutant and examined the developmental phenotypes upon induction. Under non-inducing conditions, the OEvadA mutant produced a comparable number of asexual spores compared to WT. However, when induced, overexpression of vadA resulted in significantly enhanced production of conidiospores (Fig 5). Collectively, these results support the idea that vadA is necessary for balancing asexual and sexual development, and VadA may act as an activator of asexual development.

Fig 5. Effects of overexpression of vadA.

(A) WT (THS30.1) and vadA overexpression (THS 40.1) strains were point inoculated onto solid MMG (non-inducing; left panel) or MMT (100 mM threonine, inducing; right panel) and photographed at day five. (B) Effects of overexpression of vadA on conidia formation. Quantification was done as described in the experimental procedures (** P < 0.01).

Discussion

The velvet regulators are fungal NF-κB-type transcript factors that regulate both development and metabolism [25, 35]. In particular, VosA and VelB (and their orthologues) form a hetero-complex that binds to the promoters of various developmental genes in A. nidulans and Histoplasma capsulatum in a sequence-specific manner [34, 35, 46]. Our previous studies demonstrated that the VosA/VelB complex regulates common targets grouped as VosA/VelB-activated developmental genes (VADs, e.g., tpsA) and VosA/VelB-inhibited developmental genes (VIDs, e.g., brlA and fksA), and that many VADs and VIDs are regulatory factors that subsequently control expression of downstream genes, leading to maturation of spores and completion of sporogenesis [35, 36]. The vadA gene is one of VADs defined in A. nidulans. In the ΔvosA or ΔvelB mutant conidia, the levels of vadA transcript are radically decreased compare to WT conidia (Fig 1A). Our previous chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by microarray (ChIP-chip) analysis showed that the promoter region of vadA was enriched with VosA [35]. Based on the result of MEME (Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation) analysis, we proposed a predicted VosA-VelB binding site in the vadA promoter region (-245 CTACCCCAGGC -234). These results imply that the expression of vadA in conidia might be directly activated by VosA and VelB.

VadA is a hypothetical protein that contains a highly conserved DUF at the N-terminus (Fig 1C). The ePESTfind (http://emboss.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/emboss/epestfind) program predicted that VadA has a putative PEST sequence for rapid degradation at the C-terminus (397-HTGFYPTSASSLSDPSSSAELLPTPR-422). In addition, VadA contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS)-pat4 (51-HKKR-54) and might be localized in the nucleus (56.5%), as predicted by PSORT II (http://psort.hgc.jp/form2.html). VadA is required for proper regulation of several developmental genes such as brlA, fkaA, and rodA in conidia. Taken together, we propose that VadA is a novel regulator involved in transcriptional control of spore-specific and metabolic genes during the lifecycle. Further studies defining the function and the molecular mechanisms for the role of VadA in sporogenesis are needed.

VadA is a conserved in many fungi including Aspergillus species, other Ascomycota (Neurospora, Sordaria, and Fusarium), and some Glomeromycota (Rhizophagus). However, orthologues of VadA were not found in Candida albicans or Saccharomyces cerevisiae. To further test the role of the VadA homologues in other Aspergillus species, we examined the expression of vadA mRNAs in two major pathogens: A. fumigatus and A. flavus. Our preliminary data showed that transcript levels of the vadA in A. fumigatus and A. flavus are high in conidia and during the late phase of conidiation (data not shown). Moreover, in A. fumigatus, the vadA deletion mutant, similar to the ΔvadA mutant in A. nidulans, produces light green conidia that differ from WT. Taken together, these results imply that VadA is a spore-specific regulator, which plays a crucial role in sporogenesis in Aspergillus spp.

Although the mRNA of vadA is primarily detectable in conidia, VadA is also required for balanced progression of asexual and sexual development (Figs 2 and 5). The ΔvadA mutant exhibited increased production of sexual fruiting bodies, and overexpression of vadA caused elevated formation of conidiospores, suggesting that VadA may act as an activator of asexual development. We then examined the phenotypes of the vadA overexpression (OE) mutant strain in liquid submerged culture and found that the ΔvadA mutant cannot produce conidia or activate brlA expression, implying that VadA indirectly activates asexual development in A. nidulans.

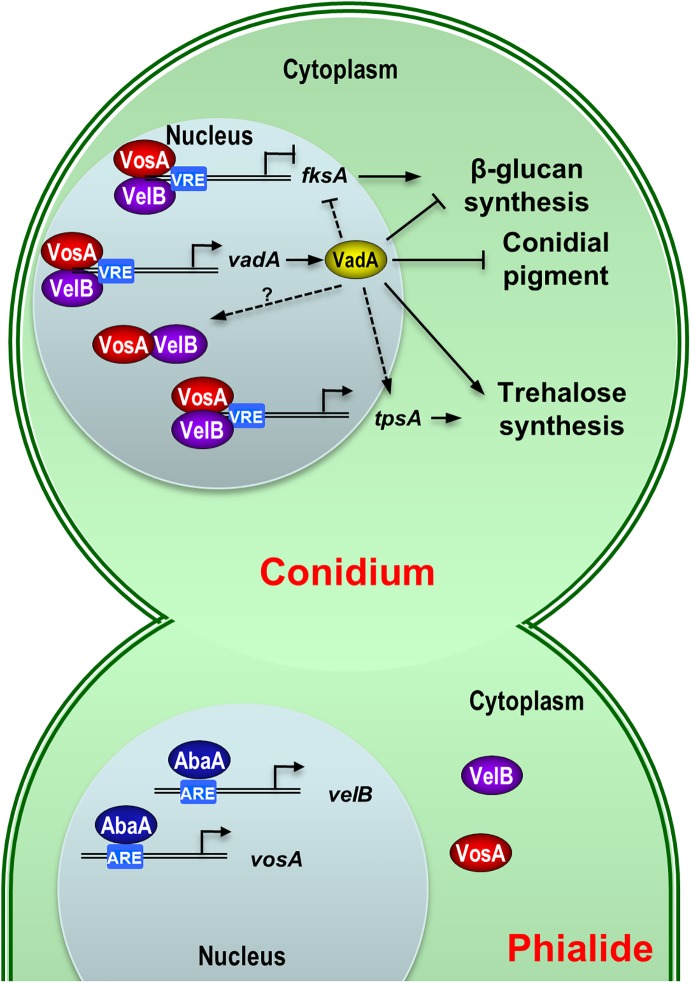

Taken together, we present a working model for the VadA-mediated regulation of sporogenesis in A. nidulans (Fig 6). In phialides, vosA and velB are activated by AbaA [23], and the two proteins form a hetero-complex then localize in in the conidial nucleus. This VosA-VelB heterodimer binds directly to the VosA-Responsive Element (VRE) present in the promoter region of vadA and activates expression of vadA. VadA is then involved in the downregulation of brlA, fksA, and rodA and the proper expression of tpsA and orlA in conidia, thereby exerting the integrity and vaiblity of conidia. The molecular mechanism of vadA-mediated sporogenesis, as well as the genetic position of VadA, will help to understand the regulatory networks governing sporogenesis in association with VosA/VelB.

Fig 6. Model for VadA-mediated regulation of conidiogenesis in A. nidulans.

A proposed model for the VadA-mediated conidiogenesis is presented (see Discussion).

Supporting information

WT (FGSC4) and ΔvadA (THS33.1~3) strains were stationary cultured in liquid completed medium at 30°C for 7 days. ST was extracted as described and subjected to TLC. ST standard was loaded as a positive control. Red arrow indicates ST.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wendy Bedale of our institute for critically reviewing the manuscript. The work by HSP was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant to HSP founded by the Korea government (MSIP: No. 2016010945). This work was in part supported by the Intelligent Synthetic Biology Center of Global Frontier Project (2011–0031955) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology grants to SCK and JHY.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The work by HSP was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant to HSP founded by the Korea government (MSIP: No. 2016010945). This work was in part supported by the Intelligent Synthetic Biology Center of Global Frontier Project (2011-0031955) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology grants to SCK and JHY. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bennett JW. An Overview of the Genus Aspergillus. Aspergillus: Molecular Biology and Genomics. 2010:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samson RA. Current taxonomic schemes of the genus Aspergillus and its teleomorphs. Biotechnology. 1992;23:355–90. Epub 1992/01/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Vries RP, Riley R, Wiebenga A, Aguilar-Osorio G, Amillis S, Uchima CA, et al. Comparative genomics reveals high biological diversity and specific adaptations in the industrially and medically important fungal genus Aspergillus. Genome Biol. 2017;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gugnani HC. Ecology and taxonomy of pathogenic aspergilli. Frontiers in bioscience: a journal and virtual library. 2003;8:s346–57. Epub 2003/04/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casselton L, Zolan M. The art and design of genetic screens: filamentous fungi. Nature reviews Genetics. 2002;3(9):683–97. Epub 2002/09/05. doi: 10.1038/nrg889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinelli SD. Aspergillus nidulans as an experimental organism. Progress in industrial microbiology. 1994;29:33–58. Epub 1994/01/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebbole DJ. The Conidium. Cellular and Molecular Biology of Filamentous Fungi. 2010:577–90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mims CW, Richardson EA, Timberlake WE. Ultrastructural analysis of conidiophore development in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans using freeze-substitution. Protoplasma. 1988;144(2–3):132–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timberlake WE. Molecular genetics of Aspergillus development. Annual review of genetics. 1990;24:5–36. Epub 1990/01/01. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.000253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams TH, Wieser JK, Yu J-H. Asexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR. 1998;62(1):35–54. Epub 1998/04/08. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC98905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park H-S, Yu J-H. Genetic control of asexual sporulation in filamentous fungi. Current opinion in microbiology. 2012;15(6):669–77. Epub 2012/10/25. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boylan MT, Mirabito PM, Willett CE, Zimmerman CR, Timberlake WE. Isolation and physical characterization of three essential conidiation genes from Aspergillus nidulans. Molecular and cellular biology. 1987;7(9):3113–8. Epub 1987/09/01. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC367944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirabito PM, Adams TH, Timberlake WE. Interactions of three sequentially expressed genes control temporal and spatial specificity in Aspergillus development. Cell. 1989;57(5):859–68. Epub 1989/06/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu J-H. Regulation of Development in Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Mycobiology. 2010;38(4):229–37. Epub 2010/12/01. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3741515. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2010.38.4.229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ni M, Gao N, Kwon N-J, Shin K-S, Yu J-H. Regulation of Aspergillus Conidiation. Cellular and Molecular Biology of Filamentous Fungi. 2010:559–76. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams TH, Deising H, Timberlake WE. brlA requires both zinc fingers to induce development. Molecular and cellular biology. 1990;10(4):1815–7. Epub 1990/04/01. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC362292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams TH, Boylan MT, Timberlake WE. brlA is necessary and sufficient to direct conidiophore development in Aspergillus nidulans. Cell. 1988;54(3):353–62. Epub 1988/07/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrianopoulos A, Timberlake WE. The Aspergillus nidulans abaA gene encodes a transcriptional activator that acts as a genetic switch to control development. Molecular and cellular biology. 1994;14(4):2503–15. Epub 1994/04/01. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC358618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrianopoulos A, Timberlake WE. ATTS, a new and conserved DNA binding domain. The Plant cell. 1991;3(8):747–8. Epub 1991/08/01. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC160041. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.8.747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sewall TC, Mims CW, Timberlake WE. Conidium differentiation in Aspergillus nidulans wild-type and wet-white (wetA) mutant strains. Developmental biology. 1990;138(2):499–508. Epub 1990/04/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall MA, Timberlake WE. Aspergillus nidulans wetA activates spore-specific gene expression. Molecular and cellular biology. 1991;11(1):55–62. Epub 1991/01/01. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC359587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ni M, Yu J-H. A novel regulator couples sporogenesis and trehalose biogenesis in Aspergillus nidulans. PloS one. 2007;2(10):e970 Epub 2007/10/04. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1978537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park H-S, Ni M, Jeong K-C, Kim YH, Yu J-H. The role, interaction and regulation of the velvet regulator VelB in Aspergillus nidulans. PloS one. 2012;7(9):e45935 Epub 2012/10/11. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3457981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarikaya Bayram O, Bayram O, Valerius O, Park H-S, Irniger S, Gerke J, et al. LaeA control of velvet family regulatory proteins for light-dependent development and fungal cell-type specificity. PLoS genetics. 2010;6(12):e1001226 Epub 2010/12/15. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2996326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayram O, Braus GH. Coordination of secondary metabolism and development in fungi: the velvet family of regulatory proteins. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2012;36(1):1–24. Epub 2011/06/11. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park H-S, Yu J-H. Velvet Regulators in Aspergillus spp. Microbiology Biotechnology Letter. 2016;44(4):409–19. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayram O, Krappmann S, Ni M, Bok JW, Helmstaedt K, Valerius O, et al. VelB/VeA/LaeA complex coordinates light signal with fungal development and secondary metabolism. Science. 2008;320(5882):1504–6. Epub 2008/06/17. doi: 10.1126/science.1155888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park H-S, Nam TY, Han KH, Kim SC, Yu J-H. VelC positively controls sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. PloS one. 2014;9(2):e89883 Epub 2014/03/04. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3938535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim H, Han K, Kim K, Han D, Jahng K, Chae K. The veA gene activates sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal genetics and biology: FG & B. 2002;37(1):72–80. Epub 2002/09/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park H-S, Bayram O, Braus GH, Kim SC, Yu J-H. Characterization of the velvet regulators in Aspergillus fumigatus. Molecular microbiology. 2012;86(4):937–53. Epub 2012/09/14. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhingra S, Andes D, Calvo AM. VeA regulates conidiation, gliotoxin production, and protease activity in the opportunistic human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryotic cell. 2012;11(12):1531–43. Epub 2012/10/23. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3536283. doi: 10.1128/EC.00222-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato N, Brooks W, Calvo AM. The expression of sterigmatocystin and penicillin genes in Aspergillus nidulans is controlled by veA, a gene required for sexual development. Eukaryotic cell. 2003;2(6):1178–86. Epub 2003/12/11. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC326641. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.6.1178-1186.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calvo AM, Bok J, Brooks W, Keller NP. veA is required for toxin and sclerotial production in Aspergillus parasiticus. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2004;70(8):4733–9. Epub 2004/08/06. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC492383. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4733-4739.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beyhan S, Gutierrez M, Voorhies M, Sil A. A temperature-responsive network links cell shape and virulence traits in a primary fungal pathogen. PLoS biology. 2013;11(7):e1001614 Epub 2013/08/13. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3720256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmed YL, Gerke J, Park H-S, Bayram O, Neumann P, Ni M, et al. The velvet family of fungal regulators contains a DNA-binding domain structurally similar to NF-kappaB. PLoS biology. 2013;11(12):e1001750 Epub 2014/01/07. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3876986. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park H-S, Yu YM, Lee M-K, Maeng PJ, Kim SC, Yu J-H. Velvet-mediated repression of beta-glucan synthesis in Aspergillus nidulans spores. Scientific reports. 2015;5:10199 Epub 2015/05/12. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4426670. doi: 10.1038/srep10199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kafer E. Meiotic and mitotic recombination in Aspergillus and its chromosomal aberrations. Advances in genetics. 1977;19:33–131. Epub 1977/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKnight GL, Kato H, Upshall A, Parker MD, Saari G, O'Hara PJ. Identification and molecular analysis of a third Aspergillus nidulans alcohol dehydrogenase gene. The EMBO journal. 1985;4(8):2093–9. Epub 1985/08/01. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC554467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waring RB, May GS, Morris NR. Characterization of an inducible expression system in Aspergillus nidulans using alcA and tubulin-coding genes. Gene. 1989;79(1):119–30. Epub 1989/06/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaaban MI, Bok JW, Lauer C, Keller NP. Suppressor mutagenesis identifies a velvet complex remediator of Aspergillus nidulans secondary metabolism. Eukaryotic cell. 2010;9(12):1816–24. Epub 2010/10/12. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3008278. doi: 10.1128/EC.00189-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwon N-J, Shin K-S, Yu J-H. Characterization of the developmental regulator FlbE in Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal genetics and biology: FG & B. 2010;47(12):981–93. Epub 2010/09/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu J-H, Hamari Z, Han K-H, Seo J-A, Reyes-Dominguez Y, Scazzocchio C. Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulations in filamentous fungi. Fungal genetics and biology: FG & B. 2004;41(11):973–81. Epub 2004/10/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park H-S, Yu J-H. Multi-copy genetic screen in Aspergillus nidulans. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;944:183–90. Epub 2012/10/16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-122-6_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seo J-A, Guan Y, Yu J-H. Suppressor mutations bypass the requirement of fluG for asexual sporulation and sterigmatocystin production in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics. 2003;165(3):1083–93. Epub 2003/12/12. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1462808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robert X, Gouet P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42(Web Server issue):W320–4. Epub 2014/04/23. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4086106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts RG. The velvet underground emerges. PLoS biology. 2013;11(12):e1001751 Epub 2014/01/07. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3876988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

WT (FGSC4) and ΔvadA (THS33.1~3) strains were stationary cultured in liquid completed medium at 30°C for 7 days. ST was extracted as described and subjected to TLC. ST standard was loaded as a positive control. Red arrow indicates ST.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.