Abstract

Transportation is inevitable in the poultry industry, and it can induce stress to chicks in varying degrees, such as mild discomfort, sometimes even death. However, the research about the effects of transport stress on the weight loss and heart injury of chicks is lacking. To elucidate the underlying mechanism of transport stress-induced effects, chicks were transported for 2h, 4h and 8h. The creatinine kinase (CK) activities, the ionic contents, the ATPases activities and the transcription of the ATPase associated subunits in chick heart were detected. The results showed that transport stress increased the weight loss and the CK activity, disturbed the ionic (K+, Ca2+, Mg2+) homeostasis and inhibited the ATPase (Na+-K+-ATPase, Ca2+-ATPase, Mg2+-ATPase and Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase) activities, increased the ATP content and downregulated the gene expression levels of the ATPase associated subunits in heart. In conclusion, transport stress disturbed the ionic homeostasis via modulating ion transporting ATPases and the transcriptions of the associated subunits, and ultimately induced weight loss and heart injury in chicks.

Keywords: transport stress, weight loss, heart injury, ionic disorder, ATPase, Pathology Section

INTRODUCTION

Stress is a kind of environmental effect on someone, and it may burden its control systems and induce mild discomfort [1]. Animals are often subjected to all kinds of stress in production practice, such as heat stress, cold stress, chemical stress, transport stress and so on. Moreover, transport stress is one of the most common stresses. Transport is inevitable to most of the farmed animals at some period of their lives, sometimes they are transported to another place to be raised, sometimes they are transported to another owner, and sometimes they are transported to slaughter. Together with the social factors (crowding and novel environment, etc.), the physical factors including temperature, noise, a lack of water and feed make the road transport very complicated [2]. So transport stress should be one of the major concerns in animal industry.

Superposition of various stimuli influence animal growth and immunologic function, and cause tissue damage and even death [3]. Previous studies have also reported that transport stress has adverse effects not only on the growth performance, market weight and meat quality of pigs, but also behavioral and biochemical responses of their bodies or peripheral organs of metabolic [4–6]. Mimicking transport stress also induced significant decreases in body weight, disturbance of the organism and significant morphological damage and apoptosis of the intestinal epithelium in rat [7].

Road transport is unavoidable in the poultry industry, and it could cause stress to birds in varying degrees, varying from mild discomfort to death. The effects of the transport on the chicks are associated with various factors, including loading density, temperature, humidity, transit duration and so on [8]. These factors are known to increase body weight loss, as well as the incidence of dead, non-ambulatory, and lame animals during and after the transport [9, 10]. And the transport stress can also induce physiological and metabolic changes [11, 12], which will affect animal welfare, processing yield and meat quality [13–15]. What is worse, it often eventually leads to increased morbidity and mortality, poor meat quality and weight loss, consequently a substantial economic loss [16–18]. It is known to us all, healthy chicks are the starting point for good production performance of poultry, however, the effects of transport stress on chicks are little known.

The previous study has demonstrated that transport stress could cause heart injury in pigs [19], and simulated transport caused damage to the hearts of rats obviously [20]. After being treated with cold stress, apparently the chicken heart tissues were damaged: the cardiac muscle fibers were ruptured, cardiocyte hypertrophy, other heart lesions and histological changes [21]. However, how the transport stress caused heart injury to the chicks is unclear.

As the most important organ and the core of the body, the heart plays an important role in the regulation of blood running and ion homeostasis, which contributes to keeping the weight off. Much evidence has showed that alterations in ion levels may be partially responsible for heart disease [22, 23]. Ionic homeostasis is especially necessary for the heart to function well [24]. Thus, it seems essential and important for cardiac function to maintain ionic homeostasis. However, little is known about the relationship between transport stress and cardiac ionic disorder. Consequently, this present study was aimed to investigate the association between transport stress-induced weight loss, and heart injury, and to assess whether modulation of the cardiac ionic balance is involved in these effects. Finally, we will provide some evidence on the effects of transport stress on chick health.

RESULTS

Body weight and biochemical analyses

Changes of weight and creatinine kinase (CK) activity in the control group and transport group were listed in Table 1. Weight loss of the chicks was found after the transport. The body weight decreased to a greater extent in the 2h, 4h, and 8h transport groups compared to control groups and the greatest decrease occurred in the 8h transport group.

Table 1. Changes of weight and CK activity of the chicks.

| Treatment | Weight (g) | CK activity (U/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before stimulation | After stimulation | Weight loss | |||

| 2h | Control | 41.28±3.564 | 40.70±3.574 | 0.580 | 5886.3±24.96 |

| Transport | 44.52±3.100 | 43.32±2.741 | 1.194 | 6035.1±339.9 | |

| 4h | Control | 40.57±2.842 | 39.76±2.559 | 0.807 | 5631.3±76.50 |

| Transport | 40.80±3.529 | 39.98±3.464 | 0.815 | 6325.6±312.9* | |

| 8h | Control | 42.82±2.255 | 41.58±2.003 | 1.235 | 5760.4±288.2 |

| Transport | 43.24±2.871 | 41.61±2.759 | 1.628 | 7105.0±263.9** | |

Values were expressed as mean ± S.D.. Symbol for the significance of differences between the transport group and control group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

To evaluate the degree of transport stress susceptibility in chicks, we firstly investigated the activity of CK in serum, which was the classic index of myocardial injury. As shown in Table 1, when compared with the corresponding control groups, the CK activity increased in all the transport groups and the increase was significant in the 4h and 8h transport groups (P < 0.05, P < 0.01; Table 1), which indicated that chick heart suffered an injury and continuous stress made it much worse.

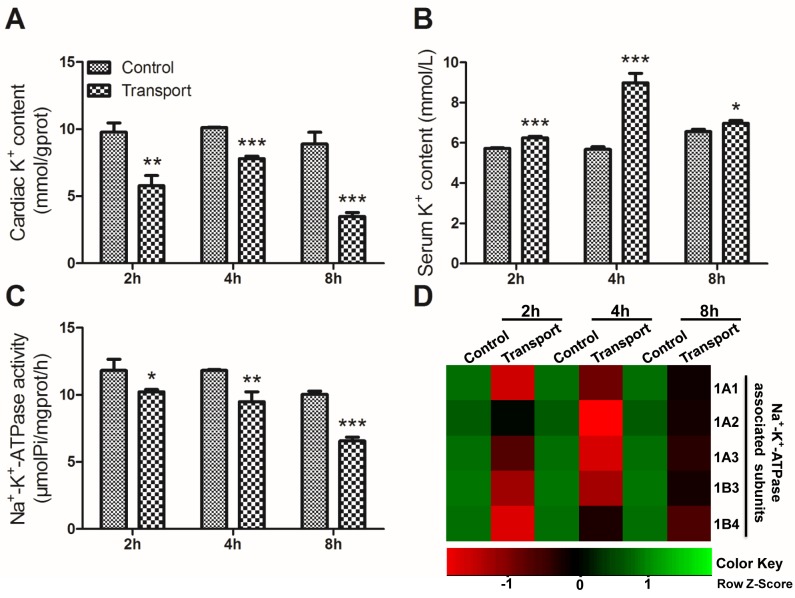

Determination of K+ content, the activity of Na+-K+-ATPase and the transcription of Na+-K+-ATPase associated subunits

The cardiac K+ content in all the transport groups was decreased compared with that of control group (P < 0.01 or P < 0.001; Figure 1A). In comparison with control group, the serum K+ content performed significant increase in the 2h, 4h and 8h transport groups (P < 0.001 or P < 0.05; Figure 1B). Changes of cardiac Na+-K+-ATPase activities in the transport groups were shown in Figure 1C. The results showed that a notable decrease in Na+-K+-ATPase activity was found in the 2h transport group (P < 0.05) compared to control group, and the decreases were much more significant in the 4h and 8h transport groups (P < 0.01, P < 0.001) compared to the corresponding control groups, which showed that a longer time of transport led to a much more serious heart injury.

Figure 1. Effects of transport stress on the modulation of K.

+ transfer channel. A. The K+ content in cardiac myocytes of the chicks; B. The K+ content in the serum of the chicks; C. The Na+-K+-ATPase activity in cardiac myocytes of the chicks; D. The heat-map of mRNA expression levels of Na+-K+-ATPase associated subunits in heart. Values were expressed as mean ± S.D.. Symbol for the significance of differences between the transport group and control group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. The mRNA expression levels of genes transcription are shown using the indicated pseudo color scale from -1 (green) to +1 (red) relative to values for control group. The Row Z-Score represents the relative mRNA expression levels, with the green indicating up-regulated genes, the red indicating down-regulated genes, and black indicating unchanged genes.

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the five Na+-K+-ATPase subunits mRNA levels showed a unique transcriptional response in the chicks treated with road transport versus the control groups (Figure 1D). It could be easily seen from the results that the transcription of the Na+-K+-ATPase subunits were down-regulated to some extent after the chicks were transported for 2h, 4h and 8h.

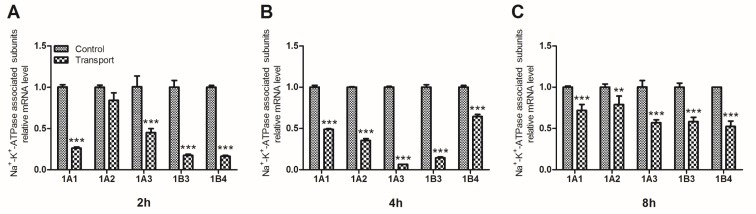

The activity of Na+-K+-ATPase was regulated by its associated subunits. These subunits mRNA levels in chick heart tissue were determined through quantitative real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) (Figure 2). The data revealed that compared to the 2h control group, the mRNA levels of four subunits (1A1, 1A3, 1B3 and 1B4) substantially decreased in 2h transport group (P < 0.001; Figure 2A). And the mRNA expression levels of Na+-K+-ATPase associated subunits (1A1-1A3, 1B3, 1B4) were also downregulated in the 4h and 8h transport group (P < 0.01 or P < 0.001), which were statistically different from the corresponding control groups (Figure 2B-2C).

Figure 2. Effects of transport stress on the mRNA expression levels of Na.

+-K+-ATPase associated subunits in chicks heart. A. 2h; B. 4h; C. 8h. Values were expressed as mean ± S.D.. Symbol for the significance of differences between the transport group and control group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

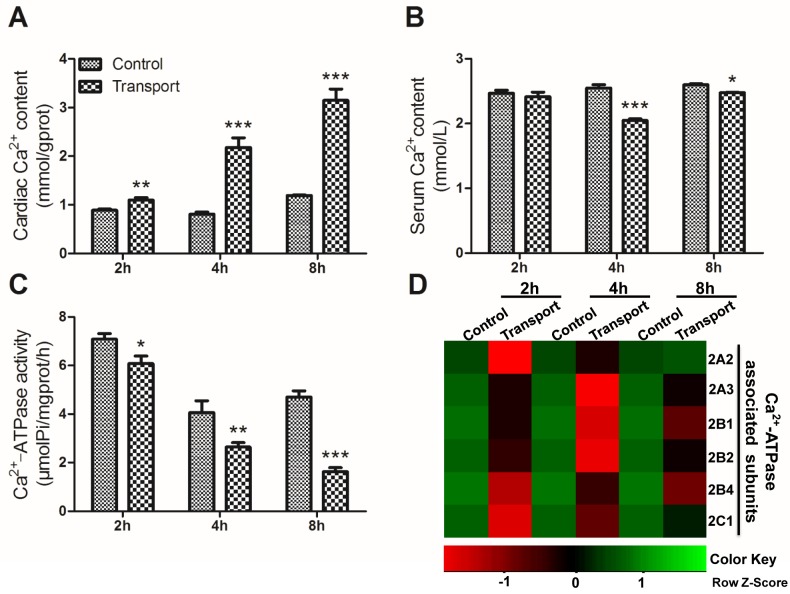

Determination of Ca2+ content, the activity of Ca2+-ATPase and the transcription of Ca2+-ATPase associated subunits

Compared to that of the 2h control group, a statistically significant increase in the cardiac Ca2+ content was observed in the 2h transport group (P < 0.01; Figure 3A), and much more remarkable increases were found in the 4h and 8h transport group (P < 0.001; Figure 3A), compared with the corresponding control groups (Figure 3A). In addition, the changes of the serum Ca2+ level failed to reach statistical significance in the 2h transport group, while significant decreases occurred in the 4h and 8h transport groups (P < 0.001, P < 0.05), compared with the corresponding control groups (Figure 3B). The alterations of the cardiac Ca2+-ATPase activity were shown in Figure 3C. Significant changes in the cardiac Ca2+-ATPase activity were observed in any transport group. The cardiac Ca2+-ATPase activity substantially decreased in the 2h transport group (P < 0.05) compared to the 2h control group, and the extent of decrease seemed to be much more significant in the 4h and 8h transport groups (P < 0.01, P < 0.001). More obvious heart damage was observed after the chicks were transported for 4h and 8h.

Figure 3. Effects of transport stress on the modulation of Ca.

2+ transfer channel. A. The Ca2+ content in cardiac myocytes of the chicks; B. The Ca2+ content in the serum of the chicks; C. The Ca2+-ATPase activity in cardiac myocytes of the chicks; D. The heat-map of mRNA expression levels of Ca2+-ATPase associated subunits in heart. Values were expressed as mean ± S.D.. Symbol for the significance of differences between the transport group and control group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. The mRNA expression levels of genes transcription are shown using the indicated pseudo color scale from -1 (green) to +1 (red) relative to values for control group. The Row Z-Score represents the relative mRNA expression levels, with the green indicating up-regulated genes, the red indicating down-regulated genes, and black indicating unchanged genes.

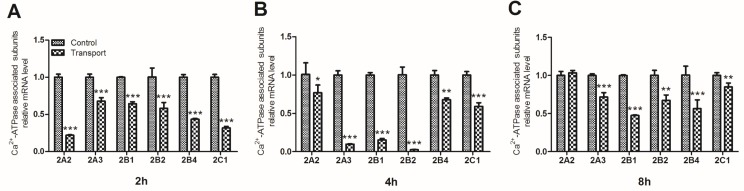

To investigate the unique transcriptional response to transport stress, a heat map showing the mRNA expression levels of the six Ca2+-ATPase associated subunits in the transported chicks was presented in Figure 3D. The transcription of the Ca2+-ATPase subunits was down-regulated evidently after the chicks were transported for 2h, 4h and 8h. The gene expression levels of the six Ca2+-ATPase associated subunits were notablely decreased in the 2h (P < 0.001; Figure 4A) and 4h transport groups (P < 0.05, P < 0.01 or P < 0.001; Figure 4B). Additionally, a remarkable decrease of the mRNA expression levels of a set of Ca2+-ATPase subunits (2A3, 2B1, 2B2, 2B4 and 2C1) was observed in the 8h transport group.

Figure 4. Effects of transport stress on the mRNA expression levels of Ca.

2+-ATPase associated subunits in chicks heart. A. 2h; B. 4h; C. 8h. Values were expressed as mean ± S.D.. Symbol for the significance of differences between the transport group and control group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

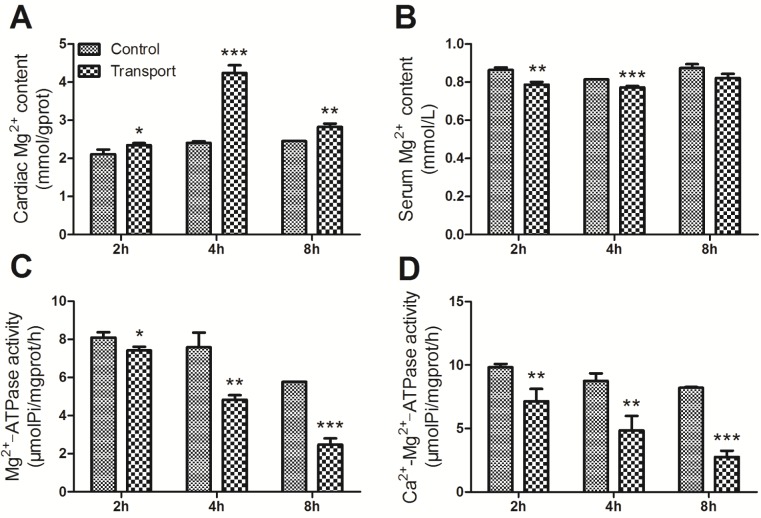

Determination of Mg2+ content, Mg2+-ATPase activity and Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase activity

Compared with the corresponding control group, the cardiac Mg2+ content displayed remarkable increase in all the transport groups (P < 0.05, P < 0.001, P < 0.01), which was shown in Figure 5A. And a statistically significant decrease in the serum Mg2+ content was found in the 2h and 4h transport group (P < 0.01, P < 0.001; Figure 5B) while there was no significant difference in the 8h transport group, compared to that of the corresponding control group. The Figure 5C showed a significant decrease in the cardiac Mg2+-ATPase activity in the 2h transport group (P < 0.05), and much more remarkable decreases were found in the 4h and 8h transport group (P < 0.01, P < 0.001). The results of Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase activity were presented in Figure 5D. The Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase activity in the 2h and 4h transport groups was suppressed significantly (P < 0.01, P < 0.01), and a more notable decrease was discovered in the 8h transport group compared to the 8h control group (P < 0.001).

Figure 5. Effects of transport stress on the modulation of Mg.

2+ transfer channel. A. The Mg2+ content in cardiac myocytes of the chicks; B. The Ca2+ content in the serum of the chicks; C. The Mg2+-ATPase activity in cardiac myocytes of the chicks; D. The Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase activity in cardiac myocytes of the chicks. Values were expressed as mean ± S.D.. Symbol for the significance of differences between the transport group and control group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

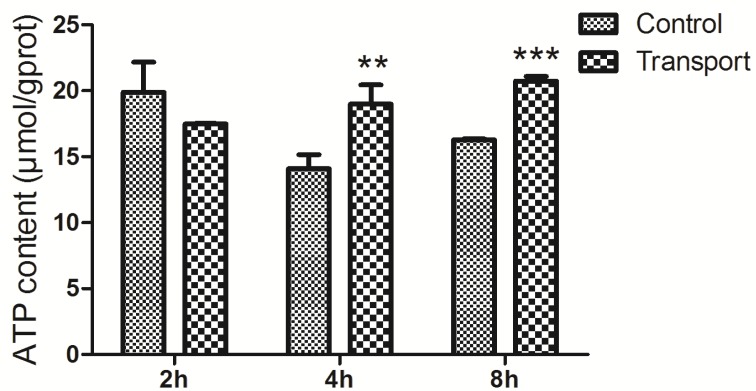

Determination of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) content in the heart tissues

The alterations of ATP content were presented in the Figure 6. Significant increases in the ATP content were observed in the 4h (P < 0.01) and 8h (P < 0.001) transport group compared to that of the corresponding control groups, whereas no notable difference was found in the 2h transport group.

Figure 6. Effects of transport stress on the ATP content in the chicks heart.

Symbol for the significance of differences between the transport group and control group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

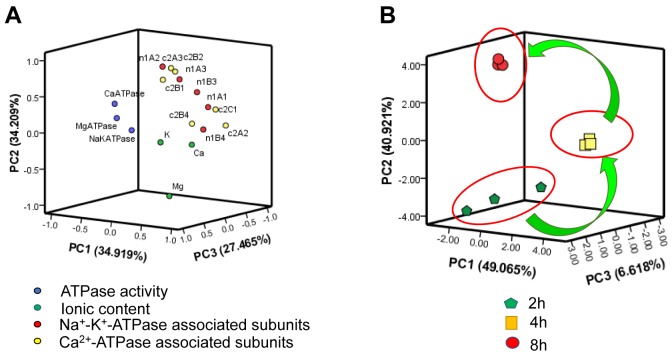

PCA of cardiac ionic homeostatic modulation

The information from intercorrelated variables was simplified into some principal components through the linear transformation of original variables by using principal component analysis (PCA). In the present study, all the parameters were divided into the first, second and third principle components based on ordination plots corresponding, and the results were depicted in Figure 7. The sum of PC1, PC2 and PC3 occupied at least 80% of the total variance (Table S2, S3).

Figure 7. PCA of ionic homeostatic modulation after the transport.

A. Ordination diagram of PCA of biochemical parameters in heart after the transport; B. PCA score plot results comparing biochemical parameters at 3 time points.

The results of PCA of biochemical indices in the heart of chicks subjected to the transport showed that some of the Na+-K+-ATPase associated genes (1A1, 1B3 and 1B4), Ca2+-ATPase associated gene (2A3) might play important roles in response to the heart injury induced by transport stress (Figure 7A). In addition, as an unsupervised pattern recognition method, PCA was used to distinguish potential effects of biochemical parameters in chicks transported for different time periods. The PCA scores revealed a notably time-dependent separation within the transported chicks. Moreover, the changes in metabolic profiles from 2h to 4h and 8h went on in a counterclockwise direction when these changes were obviously separated from the 2h transport group (Figure 7B). That is to say, these results indicated that the changes induced by the transport stress might be time-dependent.

DISCUSSION

Stress relevant to transport, such as vibration, capture, collision and scrape, heat and cold, thirst and hunger, and fear, has extensive influences on physiological systems in laboratory animals, and changes in the cardiovascular, endocrine, immune, central nervous and reproductive systems will be included [25]. It also reduced the animals’ live weight gain [26, 27] and the quality of animal products [28, 29], and resulted in significant weight loss in emus [30]. The posttransport body weight of all birds was significantly lower than their pretransport body weight [31]. In our present study, a greater weight loss was presented in the road transport treated chicks, which was in agreement with the previous study. Nevertheless, the mechanisms under which transport stress induces live weight loss in chicks are not fully understood.

Heart exerts important function in the regulation of blood running and ion homeostasis, which contributes to keeping the weight off. Previous study has shown that it's possible that transport stress triggers acute heart failure, and this could be one explanation for the sudden death of pigs during the transport [32]. The previous investigations demonstrated that simulated transport stress led to the injury and apoptosis of cardiomyocytes obviously [20]. It has also been reported that road transport could induce tissue damage to the heart [19]. In accordance with the previous studies, our results demonstrated that the CK activities increased significantly after the chicks were subjected to the transport, suggesting an obvious damage to the chick heart. Additionally, in the present study, the transport stress suggested a significant time-dependent effect on the CK activities detected in chick heart.

Proper ionic balance plays a key role in cardiac function [24]. Appropriate ion concentrations are crucial to ensure correct functioning of the entire body, especially the heart. It has been reported that once the ion balance is disrupted, cellular injury and disorders in cardiac function will occur [33, 34]. The changes of cardiac ATPase activities and the transcription of its subunits could disturb the ionic homeostasis and finally induce heart injury in quails [35, 36]. The heat stress caused a loss of ion homeostasis in marine crabs, which impaired the cardiac function [37]. Our findings in this research showed that the ionic homeostasis was disturbed by the transport stress and finally caused damage to the chick heart, which is in accordance with those observations.

As the member of the major category of ion transporters, ATPases are in charge of the basic metabolic and physiological activities of most substances, and they also participate in immediate release of energy. Moreover, they exert important influence in regulating the transmembrane ionic balance to maintain proper function of the vasculature [35, 36]. The previous investigations demonstrated that high temperature inhibited the mitochondrial Ca2+-ATPase activity in broilers [38]. And the heat stress could suppress Na+-K+-ATPase activity and Mg2+-ATPase activity of broiler chickens vital organs [39]. The ATPases activities in aquatics, mammals and quails decreased significantly after atrazine exposure [35, 36, 40]. In agreement with these findings, the present study showed that the transport stress caused a damage to the chicks heart and suppressed the activities of Na+-K+-ATPase, Mg2+-ATPase and Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase in chicks heart notablely. Additionally, the ATPase activities decreased more significantly when the chicks were transported for more than 2 hours. The results above in the present study indicated that the transport stress disturbed the ion homeostasis by altering the ATPase activities and the damage to the chicks heart was time dependent.

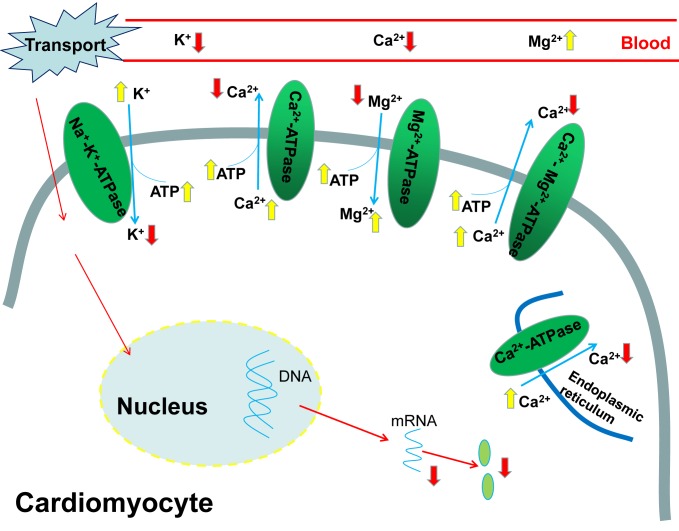

As the most important one of ionic pumps that control the absorption and secretion of Na+ and K+, the Na+-K+-ATPase is responsible for regulating the ion concentration, building and sustaining the transmembranous Na+/K+ gradient across the cell membrane [41]. As an important part of the plasma membrane, Na+-K+-ATPase transports 2K+ ions into and 3Na+ ions out of the cells using 1ATP hydrolysis. Previous investigations have demonstrated that the heat stress significantly reduced Na+-K+-ATPase in the intestinal mucosa of chickens [39, 42]. The atrazine exposure could induce Na+, K+ disorders via disruption of Na+-K+-ATPase [35, 36, 40]. However, to our knowledge, whether the transport stress could influence the Na+ and K+ contents and cardiac Na+-K+-ATPase levels of chicks has not been documented so far. In the current study, significant decreases in cardiac K+ content, the activity of Na+-K+-ATPase and the gene expression of Na+-K+-ATPase associated subunits occurred after the road transport, and remarkable increases in the serum K+ content were also found at the same time, which revealed that the K+ was transported from the blood into the heart. And our results suggested that the transport stress caused heart damage to the chicks by disturbing the K+ homeostasis, and suppressing the Na+-K+-ATPase activity and subunits transcription (Figure 8).

Figure 8. The pathway of transport stress induced ionic disorder in the heart and serum.

Ca2+ exerts critical function in the excitation-contraction coupling of cardiac myocytes, maintenance of cell integrity and gene expression associated with embryonic heart's growth and development [43, 44]. When the body is in a pathological state such as heart failure, the occurrence of contractile dysfunction and arrhythmias is mainly caused by the mishandling of Ca2+ [45]. The previous studies have demonstrated that the heat stress increased the intracellular concentration of free Ca2+ [46–48]. In agreement with that, the Ca2+ disorders and heart failure were both found in our study. The transport stress resulted in accumulation of calcium in the heart and a decrease in the serum Ca2+ contents, which might indicate that the Ca2+ was transferred from the blood into the heart. Ca2+-ATPase plays a pivotal role in intracellular calcium homeostasis because it can remove calcium from the cytosol across the plasma membrane [49], and calcium accumulation occurrs when it is suppressed substantially. High temperature inhibited the mitochondrial Ca2+-ATPase activity and then resulted in increased cytoplasmic Ca2+ [38]. The results in the present study also showed that the transport stress induced Ca2+ overload and suppressed the Ca2+-ATPase activity. Therefore, the observations in our study demonstrated that the transport stress caused the Ca2+ disorder by inhibiting the activity of Ca2+-ATPase and the gene expressions of Ca2+-ATPase associated subunits in the chick heart (Figure 8).

Mg2+ plays a vital role in many cellular processes and so many studies have indicated the importance of Mg2+ in the etiology of cardiovascular pathology [50]. It has been reported that Mg deficiency enhanced the debilitating effects of ischemic injury [51] and stress sensitivity, which probably resulted in cardiovascular damage and arrhythmias [52]. It can also induce elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, alterations in membrane permeability and transport processes in cardiac cells [50]. A considerable number of enzymes such as Na+-K+-ATPase and Ca2+-ATPase, are dependent on Mg2+ directly or indirectly [53–55], and Mg2+ is especially important for those enzymes which are of the central importance in the biochemistry of the cell, particularly in energy metabolism. The inhibition of the Mg2+-ATPase activity could disturb the Mg2+ homeostasis [35]. And the results in our study are in consistent with this: the cardiac Mg2+ contents were significantly increased while the serum Mg2+ levels decreased evidently. The results in our study suggested that the Mg2+ balance was disturbed by the transport stress via suppressing Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase activity and Mg2+-ATPase activity, which ultimately induced cardiac injury (Figure 8).

ATP is mainly generated in the mitochondria and the mitochondria are responsible for roughly 90% of the energy production of the cell via oxidative phosphorylation [56]. Heart is an excellent source of mitochondria which are able to dynamically supply enough energy to the increased work. This oxidative phenotype could quickly provide a great deal of ATP for cardiac function. It has been reported that mitochondria probably have an outstanding ‘reserve capacity’ and this ‘reserve capacity’ will be consumed when the body suffers severe stress including pressure overload or ischaemia [57, 58]. When subjected to oxidative stress, the cells could utilize ‘reserve capacity’ to increase ATP synthesis via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [59, 60]. Consistent with those, the results in our present study showed that the ATP content in of chicks heart increased significantly in the 4h and 8h transport chicks, which might be a compensatory response to the heart damage. In addition, the downregulation of the ATPase activity may also contribute to the accumulation of ATP. In the present study, the finding showed that the transport induced ionic (K+, Ca2+, Mg2+) disorder in the serum and heart of chicks, the decrease of those ATPase activities, the increase of the ATP content and the downregulation of the ATPase associated subunit expression levels (Figure 8).

In conclusion, the transport stress disturbed the ionic homeostasis via modulating ion transporting ATPases and the transcriptions of the associated subunits, and ultimately induced weight loss and heart injury in chicks. Moreover, long-term transport had a greater negative effect on the chicks. These findings will help to understand how the transport stress caused damage to the chicks and aid the development of guidelines to minimize transport stress in chicks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All procedures, treatments, and animal care were strictly in compliance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Northeast Agricultural University (NEAU). The chick's models of transport stress were employed on the basis of Dadgar and Wan's experiments [7, 20, 61]. The study was carried out on clinically healthy chicks weighting about 40.0±3.8g. The animals were obtained from the Xian Feng Chicken Farm in Harbin. Briefly, 120 0-day female chicks (Hy-Line Variety White, Harbin, China) were divided into the Control and Transport groups. Chicks transport crates were employed during transport stress. A separate crate (25°C; relative humidity, 50%) was used for each replicate group: transport group was transported by road for 2h, 4h or 8h over a distance about 480 km with an average speed of 60 km/h and the control group was not subjected to road transport. Feed and water were not available to the chicks during the transport periods. 20 chicks in each group were euthanized with carbon dioxide after treatment. Then, they were slaughtered immediately via exsanguinations of the jugular vein with bistouries and the heart tissues from each chick were collected. Whole blood was centrifuged at 2500g for 10 mins to obtain serum. Remove the heart tissues from the chicks at once on an ice bag and wash them thoroughly with physiological saline solution. Then both tissues and serum were preserved at -80°C for subsequent tests. Before and after the experiment, all the animals were weighed.

Biochemical assays

Serum CK activities have been taken as important indexes of heart injury. CK activity in the serum was detected by RT-9200 semi-automatic biochemical analyzer (Rayto Life and Analytical Sciences Co., Ltd. China), using the performance rate method.

Determination of protein content

Protein content was determined by the dye-binding method of Bradford. The standard curve was constructed by using Bovine serum albumin (BSA).

Determination of the K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations in the heart and serum

About one gram of heart tissue was minced and homogenized (ten times the weight of tissue) in physiological saline and then centrifuged (3,000 g for 10 mins). The resulting clear supernatant was collected for ionic content and ATPase activity estimations. The cardiac K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations and the serum K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations were determined by using the detection kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China).

Cardiac ATPase activity assays

The assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China) were used to mensurate the activities of Na+-K+-ATPase, Ca2+-ATPase, Mg2+-ATPase and Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase in heart tissue. And the determinations of these ATPases were independent of each other, which meant the test of one ATPase couldn't be influenced by another.

Total RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

A phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate-based TRIzol reagent (Beijing Tiandi, Inc. China) was used to extract Total RNA from the heart tissue following the instructions. A spectrophotometer was used to assess the concentration and purity based on OD280/OD260 and OD260/OD230 ratios, respectively. The primers for qRT-PCR were designed using Oligo 7.22 Software (Molecular Biology Insights, Cascade, CO) and the primer sequences were shown in Table S1. qRT-PCR was performed using LightCycler® 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche, CH). The Lyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and β-actin were used as housekeeping controls to normalize the amounts of cDNA among the samples. The mRNA relative abundance was calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCT method [62] and the results were normalized to the mean of GAPDH and β-actin.

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism5.0 (GraphPad Software, USA) and SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., USA). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc pairwise comparison was used to perform the statistical analyses. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences from the control group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. Ranking of genes by degree of differential expression was analyzed with a heat map using the R Programming Language version 3.2.1. Additionally, PCA can be used to effectively simplify the information from intercorrelated into some principal components variables through linear transformation of the original variables, and it was performed in the present study to determine the foremost parameters. Then these parameters would be used as pivotal factors for individual variations using the same software. In accordance with the Spearman's test, the observed relationships among the parameters could be confirmed and quantified.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS TABLES

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by China New Century Excellent Talents in University (No. NECT-1207-02), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31572586) and Academic Backbone Project of Northeast Agricultural University (No. 15XG16). We also acknowledge the valuable help provided by Prof. Shi-Wen Xu in Northeast Agricultural University and all of the workers involved.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

GRANT SUPPORT

China New Century Excellent Talents in University (No. NECT-1207-02);

National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31572586);

Academic Backbone Project of Northeast Agricultural University (No. 15XG16).

REFERENCES

- 1.Broom DM, Johnson KG. Stress and animal welfare. Springer Science & Business Media; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broom DM. The effects of land transport on animal welfare. Rev Sci Tech. 2005;24:683–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warriss PD, Brown SN. A survey of mortality in slaughter pigs during transport and lairage. Vet Rec. 1994;134:513–5. doi: 10.1136/vr.134.20.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker BA, Mayes HF, Hahn GL, Nienaber JA, Jesse GW, Anderson ME, Heymann H, Hedrick HB. Effect of fasting and transportation on various physiological parameters and meat quality of slaughter hogs. J Anim Sci. 1989;67:334–41. doi: 10.2527/jas1989.672334x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Candiani D, Salamano G, Mellia E, Doglione L, Bruno R, Toussaint M, Gruys E. A combination of behavioral and physiological indicators for assessing pig welfare on the farm. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2008;11:1–13. doi: 10.1080/10888700701729080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perremans S, Randall JM, Rombouts G, Decuypere E, Geers R. Effect of whole-body vibration in the vertical axis on cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels in piglets. J Anim Sci. 2001;79:975–81. doi: 10.2527/2001.794975x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wan C, Yin P, Xu X, Liu M, He S, Song S, Liu F, Xu J. Effect of simulated transport stress on the rat small intestine: A morphological and gene expression study. Res Vet Sci. 2014;96:355–64. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartzkopf-Genswein KS, Faucitano L, Dadgar S, Shand P, Gonzalez LA, Crowe TG. Road transport of cattle, swine and poultry in North America and its impact on animal welfare, carcass and meat quality: a review. Meat Sci. 2012;92:227–43. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez LA, Schwartzkopf-Genswein KS, Bryan M, Silasi R, Brown F. Factors affecting body weight loss during commercial long haul transport of cattle in North America. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:3630–9. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grandin T. Perspectives on transportation issues: The importance of having physically fit cattle and pigs. Journal of Animal Science. 2001;79:E201–E7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yue HY, Zhang L, Wu SG, Xu L, Zhang HJ, Qi GH. Effects of transport stress on blood metabolism, glycolytic potential, and meat quality in meat-type yellow-feathered chickens. Poult Sci. 2010;89:413–9. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, Yue HY, Zhang HJ, Xu L, Wu SG, Yan HJ, Gong YS, Qi GH. Transport stress in broilers: I. Blood metabolism, glycolytic potential, and meat quality. Poult Sci. 2009;88:2033–41. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dadgar S, Lee ES, Leer TL, Burlinguette N, Classen HL, Crowe TG, Shand PJ. Effect of microclimate temperature during transportation of broiler chickens on quality of the pectoralis major muscle. Poult Sci. 2010;89:1033–41. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owens CM, Sams AR. The influence of transportation on turkey meat quality. Poult Sci. 2000;79:1204–7. doi: 10.1093/ps/79.8.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petracci M, Bianchi M, Cavani C. Pre-slaughter handling and slaughtering factors influencing poultry product quality. World’s Poultry Science Journal. 2010;66:17. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bianchi M, Petracci M, Cavani C. Effects of transport and lairage on mortality, liveweight loss and carcass quality in broiler chickens. Italian Journal of Animal Science. 2005;4:516–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karaman M. Effect of transport time on body performance of broilers during transit to slaughter house. Journal of animal and Veterinary Advances. 2009;8:1555–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chauvin C, Hillion S, Balaine L, Michel V, Peraste J, Petetin I, Lupo C, Le Bouquin S. Factors associated with mortality of broilers during transport to slaughterhouse. Animal. 2011;5:287–93. doi: 10.1017/S1751731110001916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu L, Bao E, Zhao R, Hartung J. Expression of heat shock protein 60 in the tissues of transported piglets. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;14:61–9. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0055-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan C, Chen Y, Yin P, Han D, Xu X, He S, Liu M, Hou X, Liu F, Xu J. Transport stress induces apoptosis in rat myocardial tissue via activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Heart Vessels. 2016;31:212–21. doi: 10.1007/s00380-014-0607-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao FQ, Zhang ZW, Wang C, Zhang B, Yao HD, Li S, Xu SW. The role of heat shock proteins in inflammatory injury induced by cold stress in chicken hearts. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2013;18:773–83. doi: 10.1007/s12192-013-0429-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawasaki R, Machado C, Reinoehl J, Fromm B, Baga JJ, Steinman RT, Lehmann MH. Increased propensity of women to develop torsades de pointes during complete heart block. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1995;6:1032–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1995.tb00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang XD. Lycopene metabolism and its biological significance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:1214S–22S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.032359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fijorek K, Puskulluoglu M, Tomaszewska D, Tomaszewski R, Glinka A, Polak S. Serum potassium, sodium and calcium levels in healthy individuals - literature review and data analysis. Folia Med Cracov. 2014;54:53–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obernier JA, Baldwin RL. Establishing an appropriate period of acclimatization following transportation of laboratory animals. ILAR J. 2006;47:364–9. doi: 10.1093/ilar.47.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kannan G, Terrill T, Kouakou B, Gazal O, Gelaye S, Amoah E, Samake S. Transportation of goats: effects on physiological stress responses and live weight loss. Journal of Animal Science. 2000;78:1450–7. doi: 10.2527/2000.7861450x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fazio E, Medica P, Alberghina D, Cavaleri S, Ferlazzo A. Effect of long-distance road transport on thyroid and adrenal function and haematocrit values in Limousin cattle: influence of body weight decrease. Vet Res Commun. 2005;29:713–9. doi: 10.1007/s11259-005-3866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stern NJ, Clavero MR, Bailey JS, Cox NA, Robach MC. Campylobacter spp. in broilers on the farm and after transport. Poult Sci. 1995;74:937–41. doi: 10.3382/ps.0740937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez MP, Palacio J, Santolaria MP, Acena MC, Chacon G, Gascon M, Calvo JH, Zaragoza P, Beltran JA, Garcia-Belenguer S. Effect of transport time on welfare and meat quality in pigs. Meat Sci. 2002;61:425–33. doi: 10.1016/s0309-1740(01)00216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menon DG, Bennett DC, Schaefer AL, Cheng KM. Transportation stress and the incidence of exertional rhabdomyolysis in emus (Dromaius novaehollandiae) Poult Sci. 2014;93:273–84. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bejaei M, Cheng KM. Effects of pretransport handling stress on physiological and behavioral response of ostriches. Poult Sci. 2014;93:1137–48. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bao E, Sultan KR, Nowak B, Hartung J. Expression and distribution of heat shock proteins in the heart of transported pigs. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2008;13:459–66. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwik-Uribe C, Smith DR. Temporal responses in the disruption of iron regulation by manganese. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:1601–10. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Payne K, Perara VS, Huang S, Baba A, Matsuda T, Yu X. Inhibition of the sodium-calcium exchanger via SEA0400 altered manganese-induced T1 changes in isolated perfused rat hearts. NMR Biomed. 2012;25:1280–5. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin J, Li HX, Xia J, Li XN, Jiang XQ, Zhu SY, Ge J, Li JL. The chemopreventive potential of lycopene against atrazine-induced cardiotoxicity: modulation of ionic homeostasis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24855. doi: 10.1038/srep24855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin J, Li HX, Qin L, Du ZH, Xia J, Li JL. A novel mechanism underlies atrazine toxicity in quails (Coturnix Coturnix coturnix): triggering ionic disorder via disruption of ATPases. Oncotarget. 2016;7:83880–92. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jørgensen LB, Overgaard J, MacMillan HA. Paralysis and heart failure precede ion balance disruption in heat-stressed European green crabs. Journal of Thermal Biology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng J, Zhang M, Zheng S, Xie P, Ma A. Effects of high temperature on multiple parameters of broilers in vitro and in vivo. Poult Sci. 2008;87:2133–9. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen CL, Sangiah S, Chen H, Roder JD, Shen Y. Effects of heat stress on Na+,K+-ATPase, Mg2+-activated ATPase, and Na+-ATPase activities of broiler chickens vital organs. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1994;41:345–56. doi: 10.1080/15287399409531848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin J, Zhao HS, Xiang LR, Xia J, Wang LL, Li XN, Li JL, Zhang Y. Lycopene protects against atrazine-induced hepatic ionic homeostasis disturbance by modulating ion-transporting ATPases. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;27:249–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheiner-Bobis G. The sodium pump. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2002;269:2424–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Z, Xie J, Wang B, Tang J. Effect of gamma-aminobutyric acid on digestive enzymes, absorption function, and immune function of intestinal mucosa in heat-stressed chicken. Poult Sci. 2014;93:2490–500. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finkbeiner S, Greenberg ME. Ca2+ channel-regulated neuronal gene expression. J Neurobiol. 1998;37:171–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rottbauer W, Baker K, Wo ZG, Mohideen MA, Cantiello HF, Fishman MC. Growth and function of the embryonic heart depend upon the cardiac-specific L-type calcium channel alpha1 subunit. Dev Cell. 2001;1:265–75. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bers DM, Despa S. Cardiac myocytes Ca2+ and Na+ regulation in normal and failing hearts. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;100:315–22. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cpj06001x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK, Hahn GM. Rapid increases in inositol trisphosphate and intracellular Ca2+ after heat shock. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;137:826–33. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)91154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calderwood SK, Stevenson MA, Hahn GM. Effects of heat on cell calcium and inositol lipid metabolism. Radiat Res. 1988;113:414–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han AY, Zhang MH, Zuo XL, Zheng SS, Zhao CF, Feng JH, Cheng C. Effect of acute heat stress on calcium concentration, proliferation, cell cycle, and interleukin-2 production in splenic lymphocytes from broiler chickens. Poult Sci. 2010;89:2063–70. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang YC, Deng JL, Xu SW, Peng X, Zuo ZC, Cui HM, Wang Y, Ren ZH. Effects of zearalenone on calcium homeostasis of splenic lymphocytes of chickens in vitro. Poult Sci. 2012;91:1956–63. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-02128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chakraborti S, Chakraborti T, Mandal M, Mandal A, Das S, Ghosh S. Protective role of magnesium in cardiovascular diseases: a review. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;238:163–79. doi: 10.1023/a:1019998702946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manju L, Nair RR. Magnesium deficiency augments myocardial response to reactive oxygen species. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;84:617–24. doi: 10.1139/y06-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seelig MS. Consequences of magnesium deficiency on the enhancement of stress reactions; preventive and therapeutic implications (a review) Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 1994;13:429–46. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1994.10718432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharikabad MN, Østbye KM, Lyberg T, Brørs O. Effect of extracellular Mg2+ on ROS and Ca2+ accumulation during reoxygenation of rat cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H344–H53. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.1.H344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gazmuri RJ, Hoffner E, Kalcheim J, Ho H, Patel M, Ayoub IM, Epstein M, Kingston S, Han Y. Myocardial protection during ventricular fibrillation by reduction of proton-driven sarcolemmal sodium influx. J Lab Clin Med. 2001;137:43–55. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2001.111693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh J, Hustler BI, Waring JJ, Howarth FC. Dietary and physiological studies to investigate the relationship between calcium and magnesium signalling in the mammalian myocardium. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;176:127–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piekarski AL, Kong BW, Lassiter K, Hargis BM, Bottje WG. Cell bioenergetics in Leghorn male hepatoma cells and immortalized chicken liver cells in response to 4-hydroxy 2-nonenal-induced oxidative stress. Poult Sci. 2014;93:2870–7. doi: 10.3382/ps.2014-04113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kingsley-Hickman PB, Sako EY, Ugurbil K, From AH, Foker JE. 31P NMR measurement of mitochondrial uncoupling in isolated rat hearts. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1545–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gong G, Liu J, Liang P, Guo T, Hu Q, Ochiai K, Hou M, Ye Y, Wu X, Mansoor A. Oxidative capacity in failing hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H541–H8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01142.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hill BG, Dranka BP, Zou L, Chatham JC, Darley-Usmar VM. Importance of the bioenergetic reserve capacity in response to cardiomyocyte stress induced by 4-hydroxynonenal. Biochem J. 2009;424:99–107. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hill BG, Higdon AN, Dranka BP, Darley-Usmar VM. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell bioenergetic function by protein glutathiolation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:285–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dadgar S, Crowe TG, Classen HL, Watts JM, Shand PJ. Broiler chicken thigh and breast muscle responses to cold stress during simulated transport before slaughter. Poult Sci. 2012;91:1454–64. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.