Abstract

This study examines whether perceived stigma and discrimination moderate the associations between functional limitation, psychosocial coping resources, and depressive symptoms among people with physical disabilities. Using two waves of data from a large community study including a representative sample of persons with physical disabilities (N=417), an SEM-based moderated mediation analysis was performed. Mediation tests demonstrate that mastery significantly mediates the association between functional limitation and depressive symptoms over the study period. Moderated mediation tests reveal that the linkage between functional limitation and mastery varies as a function of perceived stigma and experiences of major discrimination and day-to-day discrimination, however. The implications of these findings are discussed in the context of the stress and coping literature.

Keywords: Depressive symptoms, functional limitation, stigma and discrimination, mastery

INTRODUCTION

A sizable portion of the U.S. population now experiences some form of physical disability, which is defined as a condition that impairs one’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities (IADLs), or more complex work and social activities (Verbrugge & Jette, 1994). The U.S. Census estimates that 56.7 million people – or nearly one-fifth of the population – experience a physical disability (Brault, 2012). It is also estimated that the degree of impairment – defined as one’s level of functional limitation (Verbrugge & Jette, 1994) – is severe for 38.3 million people (12.6 percent of the population) (Brault, 2012).

Estimates of physical disability and functional limitation in the population raise concern because of their association with a host of secondary physical and mental health complaints, the most prevalent of which is depressive symptoms (Alang, McAlpine & Henning-Smith, 2014; Hughes et al., 2001; Nosek & Hughes, 2003). For example, people with physical disabilities are found to experience as much as three times the number of depressive symptoms as the general population (Mirowsky & Ross, 1999), and greater functional limitation is associated with greater depressive symptoms both cross-sectionally and over time (Breslin et al., 2006; Caputo & Simon, 2013; Yang, 2006). This pattern of findings has spurred interest in the question of what social or psychological risk factors link functional limitation with psychological distress among people with physical disabilities.

Numerous studies have drawn from a stress and coping framework (Pearlin, 1989; Pearlin et al., 1981) to investigate psychosocial coping resources such as mastery, self-esteem and perceived social support as explanations (Turner & Noh, 1988; Yang, 2006; Bruce, 2001). This work often acknowledges that adjusting to functional limitation can be difficult for people with physical disabilities because of the unique social and personal challenges that often accompany disability (Turner & Noh, 1988). However, the form and meaning of these challenges are not clearly articulated in this literature. Additionally, the tendency to compare people with physical disabilities to the general population raises concern that important sources of variation among people with disabilities may be obscured (Miller & Major, 2000). An alternative approach limited to people with physical disabilities could further detail, for example, whether the effects of limitation severity on coping resources are amplified by disability-relevant stress exposure or how such exposure, in turn, interacts with coping resources in the prediction of depressive symptoms.

Addressing these considerations, the current study draws on a minority stress perspective (Meyer, 2003) and research on physical disability-related stigma and discrimination (Crocker & Quinn, 2000; Miller & Major, 2000) to further assess whether the associations between functional limitation, coping resources, and depressive symptoms vary as a function of these disability-related stressors. Tests of the indirect and conditional effects of these stressors and the coping resources of mastery, self-esteem and social support are integrated into a parsimonious structural equation model.

A Stress and Coping Perspective

Stress and coping models recognize that multiple processes link stressor exposure and the availability of psychosocial coping resources with health outcomes (Pearlin, 1989; Pearlin et al., 1981). Of particular interest here are the effects of disability-relevant social stressors, including discrimination and feelings of devaluation, which are referred to as minority stressors (Meyer, 2003). Minority stressors are those more common or unique to people who occupy disadvantaged statuses and may require greater adaptation than what is required of people who do not occupy such statuses (Meyer, 2003; Meyer, Schwartz & Frost, 2008; Pearlin, 1989). Although the concept of minority stressors was originally developed to elaborate upon the forms of stressor exposure associated with sexual orientation (Meyer, 2003), it has been expanded to include other minority statuses such as those occasioned by race, gender or physical health status (Brown & Turner, 2012; Meyer et al., 2008). Minority stressors include discrete experiences of discrimination, ranging from major events such as being denied a job or housing as well as everyday slights such as receiving worse service at restaurants or stores than others, and one’s ongoing awareness of social devaluation or the potential for negative treatment (henceforth referred to as perceived stigma) (Corrigan & Watson, 2002; Meyer, 2003; Meyer, Schwartz & Frost, 2008).

Goffman (1963) long ago noted that, among people with physical disabilities, the experience of social devaluation can challenge one’s fundamental sense of value and worth. Subsequent research has shown that, although not all people with disabilities experience discrimination or feel stigmatized (Joachim & Acorn, 2000; Miller & Major, 2000), higher levels of perceived stigma and experiences of discrimination are associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms among people with physical disabilities (Brown, 2014; Crocker & Quinn, 2000; Mona, Cameron & Crawford, 2004; Olkin, 2002; Susman, 1994; Thorne & Paterson, 1998).

The minority stress perspective further suggests that minority stressors such as perceived stigma or the experience of discrimination may amplify the effects of other stressors or offset the benefits of one’s coping responses (Meyer, 2003; see also Crocker et al., 1998; O’Brien & Major, 2005). However, while this suggestion seems theoretically intuitive, it has not been well-integrated into stress and coping research and is notably absent from work on variation in psychological distress among people with physical disabilities. This study, thus, seeks to extend our understanding of these effects on the grounds that disability-related stressors may exacerbate the negative effects of functional limitation and/or temper the benefits of coping resources for psychological well-being.

Clarifying the Effects of Functional Limitation and Coping Resources

It should be noted that functional limitation, which is described as one of the strongest predictors of depressive symptoms (Brown & Turner, 2010), appears to exert both direct and indirect effects on psychological well-being (Brown & Turner, 2010; Turner & Noh, 1988; Yang, 2006). Functional limitation is conceptualized as a source of chronic strain, in part, because it can challenge one’s ability to direct and regulate one’s life circumstances and social relationships (Bruce, 2001). Several scholars have linked its association with diminished social relationships and self-evaluations with psychological distress (Cahill & Eggleston, 1995; Joachim & Acorn, 2000).

With respect to the coping resources included in this analysis, stress researchers have identified perceived social support, mastery and self-esteem as resources that are particularly salient in the prediction of depressive symptoms (Bruce, 2001; Taylor & Lynch, 2004; Yang, 2006). Perceived social support refers to one’s level of certainty that he or she is loved, valued and cared for by significant others (Cobb, 1976). Mastery refers to a sense of personal control (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978), whereas self-esteem refers to a positive sense of self-worth (Rosenberg, 1986). Each of these resources is associated with a decline in depressive symptoms over time among people with physical disabilities (Bruce, 2001; Taylor & Lynch, 2004; Turner & Noh, 1988). Each are also found to partly mediate the association between increases in limitation and increases in depressive symptoms over time (Brown & Turner, 2010; Yang, 2006). One nationally-representative study of older adults, however, observed that mastery and self-esteem played a stronger mediating role than social resources – explaining about half of the effect of functional limitation on depressive symptoms (Yang, 2006); this finding also reinforces other observations that an inability to manage or control one’s limitations can be psychologically devastating (Jacoby, 1994).

Prior research additionally supports the possibility that the associations between functional limitation, coping resources, and depressive symptoms vary as a function of disability-related stress exposure. A moderated mediation approach (Preacher, Rucker & Hayes, 2007) can provide information on whether the mediating effects of the coping resources are contingent upon experiences of discrimination or perceived stigma, and clarify why this is so.

One possibility is that functional limitation and disability-related stressors jointly tax one’s coping resources, thereby influencing psychological well-being. This possible linkage is represented as the first potential moderating effect in Figure 1. Evidence that people with more severe functional limitations feel their relationships suffer and sense of self-worth and mastery are undermined when they experience public scrutiny and avoidance by others, or are made to feel ashamed, embarrassed, or blamed for their condition supports this proposition (Cahill & Eggleston, 1995; Earnshaw & Quinn, 2012; Miller & Major, 2000. However, it appears that no prior work has considered the combined influence of these factors for psychological well-being.

FIGURE 1.

Potential Moderating Effects of the Disability-Related Stressors on the Associations between Functional Limitation, Coping Resources and Psychological Distress

Another possibility is that the effects of functional limitation and coping resources on depressive symptoms vary as a function of how disability-related stress exposure interacts with coping resources, as indicated the second potential moderating effect in Figure 1. Supporting this consideration, several qualitative accounts indicate that people who report high levels of coping resources may be less psychologically affected by perceived stigma and discrimination (Charmaz, 2002; Darling & Heckert, 2010; Thorne & Paterson, 1998). But, they also suggest the reverse – that the beneficial effects of coping resources for psychological well-being may be eroded in the context of greater perceived stigma or frequent discriminatory encounters (Charmaz, 2002; Darling & Heckert, 2010).

Goals of the Present Study

In summary, prior research supports the hypothesis that coping resources influence depressive symptoms among people with physical disabilities over time, and partly mediate the association between functional limitation and depressive symptoms (Hypothesis 1). Given evidence that these mediating effects observed may be conditioned by experiences of discrimination or perceived stigma, two additional hypotheses are tested: (1) The effects of functional limitation on coping resources are moderated by the disability-related stressors (Hypothesis 2); and (2) the effects of the coping resources on depressive symptoms are moderated by the disability-related stressors (Hypothesis 3).

The evaluation of these hypotheses controls for age, gender, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and variation in the experience of pain, all of which are linked with psychological well-being among people with physical disabilities (Baune et al., 2008; Brown & Turner, 2010; Bruce, 2001; Coyle & Roberge, 1992; Gayman, Brown & Cui, 2011; Yang, 2006).

METHODS

Data

Data are derived from a two-wave panel study of Miami-Dade County, Florida, residents that was undertaken in order to examine the social determinants of mental health problems among people with and without physical disabilities. Based on national age, gender, and race/ethnicity-specific rates of disability, and on the Miami-Dade County demographic structure, approximately 10,000 households were randomly screened to develop a sampling frame within which people with physical disabilities were significantly overrepresented (Turner, Lloyd & Taylor, 2006). Stratified random samples were drawn so that women and men were equally represented within the study, and so that the racial/ethnic composition of study participants would reflect that of the Miami-Dade County community.

First-wave interviews were completed from 2000 to 2001, with a success rate of 82 percent. Interviews were administered by well-trained and predominantly bilingual interviewers using computerized questionnaires in either English or Spanish, as preferred by each participant. Included in the study were 559 people who confirmed the presence of a physically-disabling health condition within the first interview. Respondents were reinterviewed three years later. The second wave of interviews achieved a success rate of 74.5%. The working sample for this study includes the 417 respondents who reported a physically-disabling health condition and provided complete responses during both interviews. Excluding are the 100 W1 participants who died in the interim and 42 W1 participants who were too ill to be interviewed.

It should be noted that, because this is a sample of people with chronic health conditions, it includes a greater proportion of older respondents than what is observed in the general population. Ages in the sample range from 20 to 93 with a median of 59, whereas the median age of the general population of Miami-Dade County in 2000 was 35.6. Also, because this sample was drawn to broadly represent people with physical disabilities in this community, it is heterogeneous with respect to the types of health conditions reported and their age of onset. A limitation of this sampling approach is that individual categories of health conditions include too few cases to examine variation by health condition. The distribution of primary conditions giving rise to physical disability reported during the initial interview is presented as Table 1. The mean age of onset of a health condition reported during the first interview is 45, though the sample includes people with congenital conditions and those whose conditions occurred after age 80. A consistent pattern of findings is observed in sub-group analyses by age of onset and Wald tests demonstrate that age of onset does not significantly improve model fit. For these reasons, age of onset is not included as a predictor in the analyses to be presented.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of Primary Disabling Conditions (W1)

| Condition | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Arthritis (non-rheumatoid) | 46 | 11.0 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 45 | 10.8 |

| Musculoskeletal injury, including amputation | 45 | 10.8 |

| Brain substance including Parkinsonism, cerebral palsy, post-head injury | 40 | 9.6 |

| Back pain, including back problems and whiplash | 31 | 7.4 |

| Heart diseases including rheumatic fever, acute myocardial infarction, subacute and chronic ischemic heart disease, pulmonary heart disease, others | 27 | 6.4 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases including stroke, brain aneurysm, brain hemorrhage | 21 | 5.1 |

| Emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 15 | 3.6 |

| Cancer | 15 | 3.6 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 15 | 3.6 |

| Spinal cord, multiple sclerosis, peripheral nerve disorders, polio, primary muscle disease | 15 | 3.6 |

| Osteoarthritis of spine, degenerative disk disease | 14 | 3.4 |

| Metabolic disease, organ disease (other than heart) | 12 | 2.8 |

| Blindness – complete and partial | 11 | 2.6 |

| HIV, hepatitis, other infectious disease | 10 | 2.3 |

| Osteoarthritis (other than spine) | 9 | 2.3 |

| Asthma | 7 | 1.7 |

| Acquired deformities of the spine – scoliosis, fusion of the spine | 6 | 1.4 |

| Congenital deformity (not otherwise classified) | 4 | 1.0 |

| Hearing impairment | 3 | 0.8 |

| Other | 26 | 6.2 |

|

| ||

| Total | 417 | 100.0 |

Measures

Summary statistics for all study variables are found in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Variables (N=417)

| Characteristics | Range | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive Symptoms | |||

| W1 | 0–50 | 14.081 | 7.928 |

| W2 | 0–44 | 13.981 | 7.918 |

| Functional Limitation | 5 – 80 | 36.503 | 14.568 |

| Perceived Stigma | 0 – 35 | 10.710 | 5.181 |

| Major Discrimination | 0 – 6 | 1.185 | .722 |

| Day-to-Day Discrimination | 0 – 40 | 4.423 | 6.351 |

| Social Support | 0 – 64 | 53.745 | 11.227 |

| Mastery | 7 – 35 | 23.765 | 6.546 |

| Self-Esteem | 6 – 30 | 27.161 | 3.643 |

| Age | 20–93 | 59.787 | 15.191 |

| Sex (% female) | 0,1 | 56.5 | – |

| Socioeconomic Status | .667–14 | 6.372 | 2.486 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0,1 | 23.50 | – |

| African American | 0,1 | 39.33 | – |

| Cuban | 0,1 | 21.10 | – |

| Non-Cuban Hispanic | 0,1 | 16.07 | |

| Bodily Pain | 0 – 25 | 8.63 | 8.28 |

Note: Values reported at W1 except where noted.

Depressive symptoms

The outcome variable, depressive symptoms, is assessed at W2, with W1 levels controlled in the analyses to assess changes in symptoms across the two waves of data. Depressive symptoms are estimated using a modified version of the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977), for which there is ample evidence of reliability and validity. This abbreviated 16-item measure excludes somatic complaints in order to avoid potential confounding of mental and physical health status based on the criteria proposed by Kohout and colleagues (1993). The summated measure has high reliability (W1 α =.85; W2 α =.89) and produces results similar to the full scale.

Independent variables

Included as independent variables are W1 measures of functional limitation, perceived stigma, major and day-to-day discrimination, social support, mastery and self-esteem.

The measure of functional limitation, introduced by Turner and colleagues (Brown & Turner, 2010; Gayman, Turner & Cui, 2008), is based on the models of disability proposed by the World Health Organization [40], combining ADLs, IADLs and physical mobility items. Pooling from several previously-employed measures (Gayman et al., 2008), this standardized measure (α = .91) is based on 19 questions gauging level of functional limitation, ranging from not at all (1) to completely (5). The items used in the construction of this index are reported by Gayman and colleagues (2008).

Perceived stigma is assessed by a seven-item index (α = .91) drawn from summed responses, ranging from never (1) to always (5), to seven statements concerning the extent to which one’s physical limitation is associated with being avoided; receiving unwanted attention; hearing rude or insensitive comments; experiencing embarrassment or shame; being blamed; feeling different; and treated as personally weak (Brown, 2014). The questions used are derived from existing perceived stigma indices (Jacoby, 1994; Link et al., 1989) and were refined in focus groups conducted among people with physical disabilities. This index is, thus, unlike previous general perceived stigma measures because its point of reference (i.e., physical limitation) is made explicit to respondents. It is also unlike previous health-related perceived stigma inventories, which focus on discrete health conditions, because it is based on the experience of physical limitation, generally defined. Factor analysis reveals that these items load on a single factor, supporting their inclusion as one index (Brown, 2014).

Major and day-to-day discrimination are each measured with eight-item inventories that consider major experiences of unfair treatment, such as being fired or denied housing, as well as more routine or relatively minor experiences, such as being treated with less courtesy than others or being insulted (Williams et al., 1997). It should be noted that the items included in these indices were not asked in reference to any particular social status that respondents might occupy. Indeed, while these measures were introduced to examine race/ethnic variation in experiences of discrimination, they were developed to assess general experiences of unfair treatment and have been applied to understanding discrimination associated with a range of social status categories (Williams, Costa & Leavell, 2010).

Assessment of social support is based upon the widely-used Provisions of Social Relations Scale, for which evidence of both reliability and construct validity is available (Turner & Noh, 1988). Participants were asked to indicate responses ranging from not at all true (1) to very true (5) to eight statements about support from friends and eight statements about support from family (such as knowing your friends/family will always be there; feeling very close to your friends/family; and feeling your friends/family really care about you). The index is a sum of these 16 items (α =.91).

Mastery is measured with the seven-item scale developed by Pearlin and Schooler (1978). The index is a summed index (α = .78) assessing the extent to which respondents feel they have control over the things that happen in their lives; are able to solve problems; can change important aspects of their lives; feel helpless (reversed); feel pushed around (reversed); are responsible for what happens in their future; and can do anything they set their mind to. Responses to each item range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Self-esteem is indexed with a shortened version (α = .70) of Rosenberg’s (1986) measure drawn from six items concerning whether respondents feel they have a number of good qualities; are a person of worth at least equal to others; are able to do things as well as most other people; have a positive self-attitude; are satisfied with themselves; and are inclined to feel they are a failure (reverse coded). Responses to each item range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Covariates

All analyses control for gender, age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status and bodily pain, as indexed at W1. Gender is coded 1 for females and 0 for males. Age is employed as a continuous measure in years. Race/ethnicity is a set of dummy variables including non-Hispanic Whites (n=98), African Americans (n=164), Cubans (n=88), and non-Cuban Hispanics (n=67). The “non-Cuban Hispanic” designation primarily represents individuals from Central America. In all regression analyses, non-Hispanic Whites will represent the reference category. Socioeconomic status is estimated in terms of three components—income, education and occupational prestige level (Hollingshead, 1957). The composite socioeconomic status measure was selected because information on household income could not be obtained for 15 percent of the sample. Scores on these three dimensions are standardized, summed, and divided by the number of measures on which each respondent provided data. As used in prior research (Gayman et al., 2008), the bodily pain measure is derived by multiplying scores on the two dimensions as an indicator of pain severity (range = 0–25).

RESULTS

Table 3 presents the inter-correlations of major study variables as a precursor to the SEM analysis. Notably, every general component of the model is associated with depressive symptoms, and in the expected directions. Greater functional limitation, perceived stigma and major discrimination are positively associated with greater depressive symptoms at W2, whereas higher levels of the coping resources considered are negatively associated with depressive symptoms. Consideration of the correlations between level of limitation and the coping resources assessed also provides some preliminary support for the mediation hypothesis (Hypothesis 1): Mastery and self-esteem are inversely associated with level of limitation.

TABLE 3.

Pairwise Correlations of Depressive Symptoms (W2) and Independent Variables (W1) (N=417)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depressive Symptoms (W2) | 1.000 | |||||||

| 2. Functional Limitation | .096* | 1.000 | ||||||

| 3. Perceived Stigma | .193* | .239* | 1.000 | |||||

| 4. Major Discrimination | .113* | −.002 | .269* | 1.000 | ||||

| 5. Day-to-Day Discrimination | .043 | −.068 | .356* | .322* | 1.000 | |||

| 6. Social Support | −.258* | .008 | −.165* | −.119* | −.096* | 1.000 | ||

| 7. Mastery | −.318* | −.216* | −.304* | −.036 | −.048 | .230* | 1.000 | |

| 8. Self-Esteem | −.275* | −.180* | −.322* | −.077 | −.102* | .274* | .288* | 1.000 |

Notes: Pearson correlation coefficients are reported.

significant at .05.

The hypothesized associations between functional limitation, coping resources, perceived stigma, the experience of discrimination and depressive symptoms were further elaborated upon in SEM analysis using Mplus software version 6.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010). Estimation of a preliminary model (Figure 2), including only functional limitation, depressive symptoms and the sociodemographic covariates, produces a just identified model and, as such, meaningful fit statistics are not provided. The standardized path coefficient from functional limitation to depressive symptoms demonstrates that greater limitation is associated with increases in depressive symptoms over the study period, net of the controls (β = .129, p < .01).

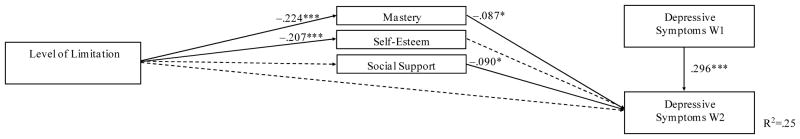

FIGURE 2. Structural Equation Model of W2 Depressive Symptoms on W1 Functional Limitation and Coping Resources (N=417).

Notes: Standardized regression coefficients reported.

A solid arrow indicates a significant effect; a dashed arrow indicates a non-significant effect;

* significant at .05; ** significant at .01; *** significant at .001.

Model controls for age, gender, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity and bodily pain.

With the addition of the coping resources to the model, the coefficient for the path from functional limitation to depressive symptoms no longer approaches significance. However, preliminary evidence of mediation is observed: Level of limitation is significantly associated with lower mastery (β = −.224, p < .001), and mastery, in turn, is associated with a decline in depressive symptoms (β = −.087, p < .05). This pattern of findings is partly consistent with the prediction of Hypothesis 1, that the coping resources assessed would mediate the association between functional limitation and depressive symptoms. It should also be noted that, although social support is associated with depressive symptoms at W2 (β = −.090, p < .05), its nonsignificant association with functional limitation does not support the mediating hypothesis (Hypothesis 1). Formal mediation tests reveal that mastery accounts for a substantial portion of the effect of functional limitation on depressive symptoms. The total effect of functional limitation on depressive symptoms in this model is .041, of which .019 (46%) is explained by its indirect effect via mastery.

Moderation tests next assessed whether the mediating effects of mastery vary as a function of perceived stigma or the experience of discrimination (Hypotheses 2 and 3). The first stage in this test examined whether the pattern of findings varies fundamentally as a function of perceived stigma and/or experiences of discrimination influencing the association between functional limitation and mastery (Hypothesis 2). Significant interactions of functional limitation with perceived stigma (β = .117, p<.05), major discrimination (β = .091, p<.05), and daily discrimination (β = .138, p<.01) are observed, as illustrated in Figure 3. These interaction effects indicate that the psychological benefits of mastery are diminished in circumstances in which functional limitation is accompanied by greater stigma and experiences of major and day-to-day discrimination, and vice versa.

FIGURE 3. Structural Equation Model of Moderating Effects of Disability-Related Stressors on the Associations between Functional Limitation, Coping Resources and Psychological Distress (N=417).

Notes: Standardized regression coefficients reported.

A solid arrow indicates a significant effect; a dashed arrow indicates a non-significant effect;

* significant at .05; ** significant at .01; *** significant at .001.

Model controls for age, gender, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity and bodily pain.

The next stage in this test considered whether the pattern of findings vary as a function of perceived stigma, major discrimination and day-to-day discrimination influencing the association between mastery and depressive symptoms (Hypothesis 3). No significant effects are observed.

DISCUSSION

The premise of this investigation is that assessing disability-relevant social stressors within a more general stress and coping framework may provide a clearer understanding of variation in psychological distress among people with physical disabilities. To this end, this study extends our understanding of the mental health effects of perceived stigma and discrimination by demonstrating their impact on the associations between functional limitation, coping resources and depressive symptoms among people with physical disabilities.

Hypothesis 1 predicted that the availability of coping resources would contribute to variation over time in psychological distress among people with physical disabilities and help account for the effects of functional limitation. Partly supporting this prediction, social support and mastery are associated with a decline in depressive symptoms, with social support bearing the strongest influence. Mastery is additionally found to partly mediate the association between functional limitation and depressive symptoms, accounting for nearly half (46%) of the effect of functional limitation. These findings are largely consistent with earlier research among a national sample of older adults, which found psychological resources to account for about half of the association between functional limitation and depressive symptoms (Yang, 2006). The findings, thus, further highlight that an understanding the psychological effects of functional limitation requires an appreciation for associated difficulties in psychological adaptation (Bruce, 2001; Turner & Noh, 1988; Yang, 2006).

Building upon prior work, the findings of the present study specify that the effects of functional limitation are importantly influenced by disability-related stressors. Partly supporting Hypothesis 2, these stressors are found to impact the linkage between functional limitation and mastery. Specifically, the findings reveal that mastery is, on average, lower – and, therefore, less beneficial for psychological well-being – in circumstances in which functional limitation is accompanied by greater stigma and experiences of major and day-to-day discrimination. Alternately, in the context of lower perceived stigma and experiences of major and day-to-day discrimination, the influence of functional limitation on one’s sense of mastery is less pronounced. These findings, taken together, extend research indicating that greater functional limitation is linked with more frequent discriminatory encounters and feelings of stigmatization (Charmaz, 2002; Darling & Heckert, 2010; Earnshaw & Quinn, 2012), demonstrating that this ‘double hit’ has psychological consequences. One of the implications of this set of findings is that the mental health effects of functional limitation are amplified in circumstances in which they are most difficult to cope with – namely, in the context of greater discrimination and perceived stigma.

Indeed, the important linkages observed between functional limitation and perceived stigma, major discrimination and day-to-day discrimination highlight the need to further understand how functional limitation influences these disability-related stressors. Several possibilities suggested by prior research are that perceptions of stigma may vary depending upon the type of health condition involved, its duration and severity, and whether one’s limitations are visible to others (Nosek & Hughes, 2003; Rohmer & Louvet, 2009). Because this sample was heterogeneous with respect to health conditions included, individual categories included too few cases to effectively examine these issues.

It was further hypothesized that perceived stigma and the dimensions of discrimination assessed would interact with coping resources in the prediction of depressive symptoms (Hypothesis 3). Although this hypothesis is not supported by the findings, a conceptual scheme including interactions among the sources of strain and coping responses highlighted here may be useful in assessing the outcomes associated with other minority statuses (Meyer, 2003; Meyer et al., 2008). This framework may also prove useful in efforts to understand how the effects of disability-relevant stressors add to or interact with stress and coping profiles uniquely relevant to other statuses. For example, there is some indication that perceived stigma and coping styles influence mental health among men and women in ways that are gender-specific (Brown, 2014; Nosek & Hughes, 2003); it seems plausible that the effects of perceived stigma and discrimination may also be contingent upon the unique coping profiles associated with other social statuses.

Several limitations of the present study merit further comment. First, it is important to emphasize that the data employed in this study are from two waves of data collected three years apart. Future research might consider how changes in functional limitation and the range of factors considered influence psychological distress across multiple points in time. There is also a need to consider the potential for bi-directional relationships among the factors considered. Although recent study indicates that functional limitation predicts depressive symptoms whereas no evidence of a reverse association is found over a short time period (Gayman et al., 2008), it seems plausible that depressive symptoms such as self-loathing or agitation towards others, indeed, might exacerbate feelings of perceived stigma. Additionally, because this analysis draws on self-reports of functional limitation and discriminatory experiences and various perceived states of being (i.e., perceived stigma, mastery, self-esteem, and depressive state), the results might reflect, to some degree, a general tendency toward negative affect. Efforts have long been made to avoid this potential confounding of reported stressful life events and symptoms of psychological suffering by expanding on stress inventories with narrative rating methods, for example (e.g., Brown & Harris, 1978; Dohrenwend et al., 1993). Further study using methods that elicit more detailed information about stressful experiences might enrich our understanding of the pattern of findings reported.

These limitations notwithstanding, this study raises the more general point for the field that incorporating perceived stigma and discrimination in a stress and coping framework acknowledges that people who occupy disadvantaged social statuses are potentially host to a variety of negative events not experienced by those who do not occupy such statuses. In the absence of a conceptual scheme that includes such stressors, the ability to examine patterns of association among various sources of strain and coping responses may be compromised. This study demonstrates the utility of such a framework among people with physical disabilities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants RO1 DA13292 and RO1 DA016429 (to R. Jay Turner).

References

- Alang SM, McAlpine DD, Henning-Smith CE. Disability, Health Insurance, and Psychological Distress among US Adults: An Application of the Stress Process. Society and Mental Health. 2014;4:164–178. doi: 10.1177/2156869314532376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baune BT, Caniato RN, Garcia-Alcaraz MA, Berger K. Combined effects of major depression, pain and somatic disorders on general functioning in the general adult population. Pain. 2008;138(2):310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault MW. Americans with disabilities: 2010. Current population reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Breslin FC, Gnam W, Franche R, Mustard C, Lin E. Depression and activity limitations. Social Psychiatry, Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41:648–655. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO. Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. New York: Free Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RL. Psychological distress and the intersection of gender and physical disability: Considering gender- and disability-related risk factors. Sex Roles. 2014;71:171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RL, Turner RJ. Physical disability and depression: Clarifying racial/ethnic contrasts. Journal of Aging and Health. 2010;22(7):977–1000. doi: 10.1177/0898264309360573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RL, Turner RJ. Physical limitation and anger: Assessing the role of stress exposure and psychosocial resources. Society and Mental Health. 2012;2(2):69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML. Depression and disability in late life: Directions for future research. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9:102–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill SE, Eggleston R. Reconsidering the stigma of physical disability: Wheelchair users and public kindness. The Sociological Quarterly. 1995;36(4):681–698. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo J, Simon RW. Physical limitation and emotional well-being gender and marital status variations. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54(2):241–257. doi: 10.1177/0022146513484766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. The self as habit: The reconstruction of self in chronic illness. The Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. 2002;22(supplement):31S–41S. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1976;38:300–314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9(1):35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle CP, Roberge JJ. The psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) when used with adults with physical disabilities. Psychology and Health. 1992;7:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Quinn DM. Social stigma and the self: Meanings, situations, and self-esteem. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, Hebl MR, Hull JG, editors. The social psychology of stigma. New York: The Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 153–183. [Google Scholar]

- Darling RB, Heckert DA. Orientations toward disability: Differences over the lifecourse. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2010;57(2):131–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP, Raphael KG, Schwartz S, Stueve A, Skodol AE. The structured event probe and narrative rating method (SEPRATE) for measuring stressful life events. In: Goldberger L, Breznitz S, editors. Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects. 2. New York: Free Press; 1993. pp. 174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The impact of stigma in healthcare on people living with chronic illnesses. Journal of health psychology. 2012;17:157–168. doi: 10.1177/1359105311414952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayman MD, Brown RL, Cui M. Depressive symptoms and bodily pain: The role of physical disability and social stress. Stress & Health. 2011;27:52–63. doi: 10.1002/smi.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayman MD, Turner RJ, Cui M. Physical limitations and depressive symptoms: Exploring the nature of the association. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2008;63B:S219–S228. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.4.s219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Two factor index of social position. New Haven, CT: A.B. Hollingshead; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes RB, Swedlund N, Petersen N, Nosek MA. Depression and women with spinal cord injury. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. 2001;7:16–24. doi: 10.1310/sci2001-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby A. Felt versus enacted stigma: A concept revisited: Evidence from a study of people with epilepsy in remission. Social Science & Medicine. 1994;38(2):269–274. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joachim G, Acorn S. Living with chronic illness: The interface of stigma and normalization. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2000;32(3):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. Journal of Aging and Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Dohrenwend B. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:400–423. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–97. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:368–79. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Major BM. Coping with stigma and prejudice. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, Hebl Michelle R, Hull JG, editors. The social psychology of stigma. New York: The Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 243–272. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Well-being across the life course. In: Horwitz AV, Scheid TL, editors. Handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 328–347. [Google Scholar]

- Mona LR, Cameron RP, Crawford D. Stress and trauma in the lives of women with disabilities. In: Kendall-Tackett KA, editor. Handbook of women, stress, and trauma. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2004. pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nosek MA, Hughes RB. Psychosocial issues of women with physical disabilities: The continuing gender debate. Rehabilitation Counseling. 2003;46:224–233. [Google Scholar]

- Olkin R. Could you hold the door for me? Including disability in diversity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2002;8:130–137. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI. The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30:241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychosocial Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rohmer O, Louvet E. Describing persons with disability: Salience of disability, gender, and ethnicity. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2009;54:76–82. doi: 10.1037/a0014445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self, second edition. Melbourne, FL: Academic Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MG, Lynch SM. Trajectories of impairment, social support and depressive symptoms in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59B:S238–246. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.s238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S, Paterson B. Shifting images of chronic illness. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1998;30(2):173–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1998.tb01275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA, Taylor J. Physical disability and mental health: An epidemiology of psychiatric and substance disorders. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2006;51(3):214–223. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Noh S. Physical disability and depression: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1988;29(1):23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;38:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Costa M, Leavell JP. Race and mental health: Patterns and challenges. In: Scheid TL, Brown TN, editors. A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010. pp. 268–290. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socioeconomic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability, and health (ICF) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. How does functional disability affect depressive symptoms in late life? The role of perceived support and psychological resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47(4):355–372. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]