Abstract

Electronic cigarette (ECIG) use is growing in popularity, however, little is known about the perceived positive outcomes of ECIG use. This study used concept mapping (CM) to examine positive ECIG outcome expectancies. Sixty-three past 30-day ECIG users (38.1% female) between the ages of 18 and 64 (M = 37.8, SD = 13.3) completed a CM module. In an online program, participants provided statements that completed a prompt: “A specific positive, enjoyable, or exciting effect (i.e., physical or psychological) that I have experienced WHILE USING or IMMEDIATELY AFTER USING an electronic cigarette/electronic vaping device is…”. Participants (n = 35) sorted 123 statements into “piles” of similar content and rated (n = 43) each statement on a 7-point scale (1-Definitely NOT a positive effect to 7-Definitely a positive effect). A cluster map was created using data from the sorting task and analysis indicated a seven cluster model of positive ECIG use outcome expectancies: Therapeutic/Affect Regulation, High/Euphoria, Sensation Enjoyment, Perceived Health Effects, Benefits of Decreased Cigarette Use, Convenience, and Social Impacts. The Perceived Health Effects cluster was rated highest, though all mean ratings were greater than 4.69. Mean cluster ratings were compared and females, younger adults, past 30-day cigarette smokers, users of more “advanced” ECIG devices, and non-lifetime (less than 100 lifetime cigarettes) participants rated certain clusters higher than comparison groups (ps < 0.05). ECIG users associate positive outcomes with ECIG use. ECIG outcome expectancies may affect product appeal and tobacco use behaviors and should be examined further to inform regulatory policies.

Keywords: electronic cigarettes, outcome expectancies, concept mapping, mixed methods

In 2016, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a final rule to regulate electronic cigarettes (ECIGs) as part of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (TCA). ECIGs are a class of products that heat a liquid that often contains a combination of propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, nicotine, and chemical flavorants; heating this liquid forms an aerosol that can be inhaled by the user. Current ECIG use in the U.S. is growing in popularity and has increased from 1.5% in 2011 to 16% in 2015 among high school students (Arrazola, Neff, Kennedy, Holder-Hayes, & Jones, 2014; Arrazola et al., 2015; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013a; CDC, 2013b; Singh et al., 2016) and 0.3% in 2010 to 3.7% in 2014 among adults (King, Patel, Nguyen, & Dube, 2015; McMillen et al., 2014; Schoenborn & Gindi, 2015). National U.S. adult ECIG use data from 2014 show that 15.9% of current cigarette smokers, 22% of former cigarette smokers who have stopped cigarette smoking in the past year, and 0.4% of never cigarette smokers are current users of ECIGs (Schoenborn & Gindi, 2015).

The popularity and growing use of EGIGs has sparked debate on their utility as a cigarette smoking cessation aid as well as their appeal to youth and non-tobacco users. However, factors that contribute to the use of ECIGs and trajectories associated with ECIG use are largely unknown, though a growing body of literature addresses reported reasons for ECIG use such as smoking cessation or reduction (Adikson et al., 2013; Berg, Haardoerfer, Escoffery, Zheng, & Kegler, 2015; Brown et al., 2014; Goniewicz, Lingas, & Hajek, 2013; Hummel et al., 2015; Kadimpati, Nolan, & Warner, 2015; Kralikova, Novak, West, Kmetova, & Hajek, 2013; Li, Newcombe, & Walton, 2015; Mark, Farquhar, Chisolm, Coleman-Cowger, & Terplan, 2015; Pepper, Ribisl, Emery, & Brewer, 2014; Peters et al., 2015; Richardson, Pearson, Xiao, Stalgaitis, & Vallone, 2014; Soule, Rosas, & Nasim, 2016c; Stein et al., 2015), utility for use where cigarette smoking is prohibited (Berg et al., 2015; Kadimpati et al., 2015; Kralikova et al., 2013; Richardson et al., 2014; Soule et al., 2016c), curiosity (Berg et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015; Pepper et al., 2014; Peters et al., 2015; Stein et al., 2015), and perceived lower costs compared to cigarettes (Kadimpati et al., 2015; Soule et al., 2016c). One construct particularly may be revealing regarding predicting future ECIG use among current non-users of ECIGs: outcome expectancies.

Outcome expectancies, a construct that emerged from Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1977; Bandura, 1986), are positive or negative consequences that one expects or believes to result from engaging in a particular behavior (Bandura, 1977; Bandura, 1986). Outcome expectancies, which can be developed through past performance of a behavior or learned from other information sources (Bandura, 1986; Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2008), are robust predictors of future behaviors including cigarette smoking initiation (Chassin, Presson, Sherman, & Edwards, 1991; Doran, Schweizer, & Myers, 2011) and smoking maintenance (Brandon & Baker, 1991; Jeffries et al., 2004; Juliano & Brandon, 2004; Gwaltney, Shiffman, Balabaris, & Paty, 2005; Wahl, Turner, Mermelstein, & Flay, 2005). Outcome expectancies may also play a critical role in the increased use of ECIGs, but few studies have investigated outcome expectancies related to ECIG use. One study that has addressed the issue among a multiethnic sample of college students identified three positive expectancies among ever users of ECIGs: social enhancement (e.g., fit in, look more attractive), affect regulation (e.g., less stress, relaxed), and positive sensory experiences (e.g., taste, smell; Pokhrel, Little, Fagan, Muranaka, & Herzog, 2014). This study also found that higher positive expectancies were associated with greater odds of using ECIGs in the past 30 days and also were associated with intention to use ECIGs in the future among never users. Similarly, another study showed that outcome expectancies including taste, satisfaction, and convenience of ECIGs were rated higher than that of cigarettes and nicotine replacement therapy among former smokers (Harrell et al., 2015b).

Further investigation of ECIG outcome expectancies may shed light on the reasons for the increasing popularity of ECIGs. In particular, there is great need to study positive outcome expectancies because positive outcome expectancies of tobacco use have been shown to be more predictive of tobacco use behavior than negative outcome tobacco use outcome expectancies (Barnett, Lorenzo, & Soule, 2016; Brandon et al., 1991; Dalton, Sargent, Beach, Bernhardt, & Stevens, 1999). Additionally, while some relevant studies have examined ECIG use outcome expectancies using items developed from cigarette smoking outcome expectancy measures (Harrell et al., 2015a; Hendricks et al., 2015; Piñeiro et al., 2016), there may be expectancies that are unique to ECIG use that may not be represented in the known cigarette smoking expectancy measures. A mixed-method approach may be better able to identify the broad range of ECIG outcome expectancies. One such approach is concept mapping (CM; Kane & Trochim, 2007; Trochim, 1989), a mixed-method participatory approach that has been used previously to examine reasons for ECIG use (Soule, Lopez, Guy, & Cobb, 2016a, Soule et al. 2016c) and adverse effects of ECIG use (Soule et al., 2015). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to identify and describe the positive outcome expectancies associated with ECIG use among adults using CM and organize these expectancies into meaningful constructs.

Methods

Overview

This study used CM to examine user perceived positive outcomes associated with ECIG use. This approach incorporates multiple steps including preparation, brainstorming, sorting, rating, representation, data analysis, and interpretation to identify and describe latent constructs related to positive ECIG outcome expectancies. Specifically, ECIG users were asked, using an online program, first to respond to a prompt and brainstorm statements related to positive outcome expectancies associated with ECIG use and then were invited to sort and rate these statements. Data from the sorting and rating tasks were used to create a visual representation (i.e., a concept map) of a final model of theoretical clusters related to positive ECIG use expectancies. This study was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board.

Concept Mapping Procedures

Preparation

An initial prompt was developed to elicit positive outcomes expectancies from ECIG users based upon a previous CM exercise (Soule, Nasim, & Rosas, 2015) and was refined, based on pilot testing (n = 5) so that the final prompt was: “A specific positive, enjoyable, or exciting effect (i.e., physical or psychological) that I have experienced WHILE USING or IMMEDIATELY AFTER USING an electronic cigarette/electronic vaping device is…”.

Participants

Recruitment

Past-30 day ECIG users between the ages of 18 and 64 were recruited by posting advertisements in six popular internet ECIG/vape forums and on Craigslist classified pages from eight cities across the U.S. Craigslist locations were chosen by randomly selecting the largest city from two states from each of the four U.S. census tract regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, West). Advertisements indicated participants would be compensated, but did not list exact study payment amount. Interested individuals contacted study staff via email and study staff replied via email and phone to confirm past 30-day ECIG use and age (between 18 and 64) and describe participant compensation. Eligible individuals (n = 79) were invited to participate in the brainstorming task, of which 63 completed it (80% response rate).

Participant Characteristics Measurement

During the brainstorming task, participants were sent a link to the CM online program (The Concept System® Global MAX™) where they completed a demographic questionnaire. The questionnaire examined ECIG use behaviors including how long participants had been using ECIGs regularly (i.e., more than once or twice per week), frequency of ECIG use during the day, ECIG device characteristics including liquid nicotine concentration, ECIG device type/characteristics, liquid flavor preferences, time to ECIG use after waking, and with whom participants used their ECIGs. Other tobacco use items examined lifetime cigarette smoking status (defined as smoking 100 cigarettes or more in your lifetime), past 30-day cigarette use, cigarette flavor preference (e.g., menthol or non-menthol), previous cigarette smoking quit attempts, and other tobacco product use. Finally, participants provided basic demographic information. Just under half of the participants were female (38.1%) with a mean age of 37.8 (SD = 13.3). Most (87.3%) were non-Hispanic, White (73.0%), and had completed at least some college or earned a college degree (74.6%). About two-thirds had been using ECIGs regularly for at least one year and reported ECIG use all of the past 30 days. Around half (46%) reported cigarette smoking in the past 30 days and 16% reported smoking less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. See Table 1 for a full description of the participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Characteristic | N = 63 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 37.8, 13.3 | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 24 | 38.1 |

| Male | 39 | 61.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 8 | 12.7 |

| Not Hispanic / Latino | 55 | 87.3 |

| Race | ||

| American Indian / Alaskan Native | 2 | 3.2 |

| Asian | 2 | 3.2 |

| Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander | 1 | 1.6 |

| Black / African American | 6 | 9.5 |

| White / European American | 46 | 73.0 |

| More than one race | 4 | 6.3 |

| Regular ECIG Use Duration | ||

| Less than a month | 1 | 1.6 |

| 1 - 3 months | 4 | 6.3 |

| 4 - 6 months | 7 | 11.1 |

| 7 - 12 months | 9 | 14.3 |

| Between 1 and 2 years | 24 | 38.1 |

| More than 2 years | 19 | 30.2 |

| ECIG Use in Past 30 Days | ||

| 1 - 5 days | 2 | 3.2 |

| 6 - 10 days | 2 | 3.2 |

| 11 - 20 days | 9 | 14.3 |

| 21 - 29 days | 7 | 11.1 |

| All 30 days | 43 | 68.3 |

| ECIG Use Times per Day | ||

| At least once per day | 2 | 3.2 |

| Every once in a while throughout the day | 10 | 15.9 |

| Fairly frequently throughout the day | 35 | 55.6 |

| More than 25 times a day | 17 | 27.0 |

| Nicotine Concentration | ||

| Zero (0mg / mL) | 7 | 11.1 |

| 3 - 4 mg / mL | 17 | 27.0 |

| 6 - 8 mg / mL | 14 | 22.2 |

| 11 - 12 mg / mL | 14 | 22.2 |

| 16 – 24 mg / mL | 7 | 11.1 |

| Don’t know | 4 | 6.3 |

| Type of Liquid Storage | ||

| Prefilled disposable / Cig-alike | 10 | 15.9 |

| Refillable cartomizer | 7 | 11.1 |

| Refillable tank or clearomizer | 34 | 54.0 |

| Drip feed / Use drip tip | 12 | 19.0 |

| Don’t know | 1 | 1.6 |

| Device Type | ||

| Cig-alike | 12 | 19.0 |

| Vape pen / eGo style product | 17 | 27.0 |

| Box mod | 28 | 44.4 |

| Rebuildable / Mechanical mod | 6 | 9.5 |

| ECIG Liquid Flavor Preference | ||

| Candy / Fruit flavor | 22 | 34.9 |

| Food / Dessert / Spices flavor (e.g., crème, vanilla, cinnamon) |

8 | 12.7 |

| Menthol flavor | 7 | 11.1 |

| Tobacco flavor | 9 | 14.3 |

| I usually use multiple flavors | 15 | 23.8 |

| I don’t use a flavor | 1 | 1.6 |

| ECIG Use with Who | ||

| By myself | 30 | 47.6 |

| With others (e.g., friends, family, co-workers) | 3 | 4.8 |

| Both by myself and with others | 30 | 47.6 |

| Lifetime Cigarette Use >100 Cigarettes | ||

| No | 10 | 15.9 |

| Yes | 53 | 84.1 |

| Cigarette Use Past 30 Days | ||

| None | 34 | 54.0 |

| 1 - 5 days | 10 | 15.9 |

| 6 - 10 days | 7 | 11.1 |

| 11 - 20 days | 6 | 9.5 |

| All 30 days | 6 | 9.5 |

Note. Regular use was defined as using an ECIG device more than once or twice per week.

Brainstorming

Participants then were instructed to provide five to eight statements that completed the focus prompt. Statements were required to be brief and relate to a single idea. While each participant completed this brainstorming activity individually, a list of all brainstormed statements was compiled as participants added their statements. Therefore, participants could see all statements that were generated by previous participants and were asked to search the statements in order to avoid providing redundant statements. The brainstorming task was closed when content saturation was reached. Participants received a $10 e-gift card for completing the brainstorming task.

Sorting and Rating

Three researchers reviewed the 389 statements generated from the brainstorming task and removed statements that did not relate to the focus prompt (e.g., “Blowing smoke in people’s trumpets.”) or were redundant. The final list of 123 statements was loaded into the CM online program for the sorting and rating tasks. Of the 63 participants invited to participate in the sorting and rating tasks, 35 completed the sorting and 43 completed the rating tasks. During the sorting task (Rosenberg & Kim, 1975; Weller & Romney, 1988), each participant organized the statements by moving the statements into “piles” of similar content in the online CM program. Participants were instructed that piles must be organized by similar content, there could not be an “other” or miscellaneous pile, there could not be as many piles as statements, there could not be a single pile with all statements, and piles could not be organized by priority or other criteria (e.g., Does not apply to me, difficult to do, true and false, etc.). Upon completion of the sorting task, each participant rated each statement based on a prompt (“For me, this is a specific positive, enjoyable, or exciting effect of using an electronic cigarette/electronic vaping device.”) on a scale from 1 (Definitely NOT a positive, enjoyable, or exciting outcome) to 7 (Definitely a positive, enjoyable, or exciting outcome). Participants received an e-gift card for completing the sorting task ($25) and the rating task ($10).

Analyses

Representation

A visual representation (i.e., a concept map) of a final model of theoretical clusters of positive ECIG use outcome expectancies was created based on participants’ sorting of brainstormed statements. Each participant generated a matrix in which a 1 was coded in the cells for statements that were sorted into the same pile during the sorting task. These matrices were aggregated across all participants creating a 123 × 123 matrix where larger cell counts represented statements that were sorted together more frequently in the sorting task. Using non-metric multidimensional scaling, each statement was assigned coordinates (x,y) in two-dimensional space using an algorithm built into the CM program that attempted to put statements that were sorted together more often in the sorting task closer to one another and statements that were rarely or never sorted together in the sorting task farther from one another. The resulting point map (Kruskal & Wish, 1978) is a two-dimensional representation of the sorting data. The stress of the model, which is an indicator of model fit of the multidimensional scaling analysis, was 0.28 and fell well within the range of stress values reported previously (Rosas & Kane, 2012) indicating good fit and congruence between the processed and raw data (Davison, 1983; Kruskal, 1964).

Analysis and Interpretation

Using a hierarchical cluster analysis (Ward, 1963), clusters of statements were identified empirically using CM software based on their two-dimensional coordinates. The research team examined multiple models by examining different numbers of clusters using a hierarchical cluster analysis. In this analysis, CM software identified two clusters of statements by using an algorithm (Ward, 1963) to define non-overlapping cluster arrangements of statements which limited the distance between points on the map to the centroid of the identified clusters. Subsequent models were generated by adding a single additional cluster to the model by separating statements from one cluster into two clusters (e.g., adding a cluster to a two cluster model would result in one cluster remaining the same and one cluster being separated into two new clusters). Therefore, each subsequent model was built on the previous models. Additional clusters were identified and added to the model using CM software and using interpretability (i.e., clusters related to one latent construct) and parsimony (i.e., fewer cluster models favored) as indicators of model fit, the team identified the optimal model of theoretical constructs. The research team discussed each model and a final model was identified when adding additional clusters did not improve interpretability of the overall model. The team then assigned names to each cluster based on the content of the statements within each cluster. Just as points on the map located close to each other represented statements related to similar content, clusters on the map in the final model represented similar content. As in a previous CM study (Soule et al., 2016b), the research team examined the clusters in the final model and determined through group discussion and consensus if any groups of clusters were related to broader constructs.

After the final concept map was established, a separate analysis was conducted using participants’ ratings of statements. Mean ratings of each statement were calculated across participants and these averages were used to compute a mean cluster rating of all statement averages within the identified clusters. Using an alpha level of 0.05, exploratory comparisons of mean cluster ratings were examined using t tests to conduct subgroup contrasts between groups based on key demographic variables including sex, age, cigarette smoking history, frequency of ECIG use, device type, flavor preferences, and social patterns of ECIG use (e.g., typically using by oneself or with others).

Results

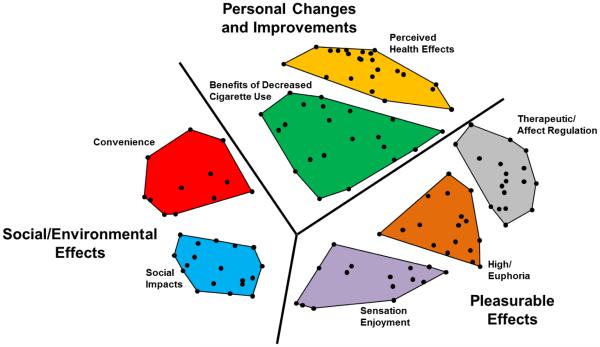

The final cluster map (Figure 1) included seven clusters of statements related to positive ECIG use outcomes identified by ECIG users. The clusters fell under three broad constructs of: Pleasurable Effects (n=49 statements), Personal Changes and Improvements (n=44 statements), and Social/Environment Effects (n=30 statements). A summary of the clusters and statements are described below, however, Table 2 lists all statements and ratings within each cluster.

Figure 1.

Concept map of positive, enjoyable, and exciting outcomes of ECIG use. Points within each cluster represent individual statements sorted by participants.

Table 2.

List of clusters and statements with mean ratings

| Cluster | Statement | Average Rating |

|---|---|---|

| Pleasurable Effects | ||

| Therapeutic/Affect Regulation | 5.09 | |

| I feel calm and relaxed | 5.65 | |

| I just feel good | 5.63 | |

| I feel a satisfied happy sensation after using my electronic cigarette | 5.63 | |

| My craving is satisfied | 5.62 | |

| I feel stress free, when I use my vape - it's very calming for me | 5.53 | |

| I feel satisfied | 5.37 | |

| I feel a sense of calm come over me | 5.33 | |

| I feel in control when I vape | 5.28 | |

| When I vape I get a pretty close psychological effect compared to what a cigarette gives me |

5.19 | |

| I feel very chill/laid back and mellow | 5.05 | |

| I find instant relief right after I vape | 5.00 | |

| My mind is at ease no pressure | 4.98 | |

| I don't feel bored when vaping | 4.98 | |

| Vaping is a great form of therapy | 4.56 | |

| Vaping raises my emotional awareness of pleasurable feelings | 4.48 | |

| Vaping can help stop the bad things in life | 3.91 | |

| I feel lighter after vaping | 3.86 | |

| High/Euphoria | 4.69 | |

| I find vaping enjoyable | 6.02 | |

| I enjoy the 'mouth-feel’ and the act of drawing vapor into my lungs | 5.53 | |

| Smooth hits feel nice | 5.51 | |

| I feel same satisfaction as I would as if I smoked regular cigarette, however I feel that I get a better taste with a vape |

5.42 | |

| Vaping is so refreshing with no heavy feeling | 5.37 | |

| Vaping helps me concentrate while working | 5.14 | |

| Vaping gives me something to do with my hands | 4.93 | |

| I enjoy the warmth of the vapor | 4.65 | |

| Vaping satisfies an oral fixation that smoking couldn't | 4.56 | |

| I am pumped up and ready to get my day started after I have my E-cig | 4.40 | |

| I have felt empowered on many different levels during and after vaping | 4.21 | |

| Vaping completes me | 4.16 | |

| I get a nice head rush | 4.14 | |

| I like when the cool vape cloud brushes past my face | 4.05 | |

| I enjoy the head buzz I get when vaping | 3.95 | |

| I get a rush with the first hit | 3.93 | |

| The metal texture feels amazing against my lips | 3.74 | |

| Sensation Enjoyment | 4.83 | |

| Vaping tastes delicious | 5.77 | |

| The sensation of the vapor and the good flavors is pleasant | 5.71 | |

| More flavor and same effect as smoking | 5.60 | |

| I get to enjoy vaping flavors never before available with smoking | 5.42 | |

| The smell and flavor is extremely refreshing | 5.38 | |

| I love the taste of the different types of e-liquid I get to try out | 5.37 | |

| While vaping, I get the enjoyment of tasting a favorite dessert or beverage without actual consumption |

5.33 | |

| My brain thinks of the actual flavor of what e-juice I am smoking | 5.00 | |

| I am much easier to be around after I vape | 4.98 | |

| I just enjoy looking at them - some of these devices are really beautiful works of art |

4.77 | |

| The clouds I make while vaping smell wonderful | 4.70 | |

| I often use vaping to remove myself from social situations for 'down time' | 4.30 | |

| I get a buzz by just seeing the device before I use it | 3.49 | |

| It is fun doing tricks | 3.47 | |

| Vaping can make you feel cool | 3.21 | |

| Personal Changes and Improvements | ||

| Perceived Health Effects | 5.66 | |

| Vaping doesn't produce toxic tobacco smoke | 6.37 | |

| Not harming my body | 6.09 | |

| Being able to smell fresh air | 6.05 | |

| My health has improved since I started vaping | 6.02 | |

| I feel proud of myself for making a healthy choice | 6.00 | |

| My breath is a lot fresher | 6.00 | |

| No yellowing of teeth | 6.00 | |

| I no longer cough all day | 5.95 | |

| I can breathe a lot better | 5.95 | |

| Since I started vaping, my lungs are clearer and I get sick much less | 5.88 | |

| Vaping feels much more safe than smoking cigarettes because I know exactly what is going into my body now |

5.84 | |

| My throat doesn't hurt when vaping | 5.72 | |

| No experience of cough while or after vaping | 5.67 | |

| The vapor doesn't contain any harsh chemicals | 5.63 | |

| I can actually run without feeling out of breath | 5.58 | |

| My lungs don't hurt anymore when exercising | 5.55 | |

| I can still feel like myself and work out, play sports, hike, or be active while being able to vape |

5.49 | |

| Vaping doesn't slow me down as much as cigarettes do when I work out | 5.49 | |

| I don't get headaches from vaping a lot | 5.44 | |

| Improved sense of smell | 5.40 | |

| I don't feel tired after I vape | 4.93 | |

| I feel energetic after vaping | 4.77 | |

| Vaping raises my energy level | 4.35 | |

| Benefits of Decreased Cigarette Use | 5.50 | |

| Vaping has cut down on my smoking dramatically | 6.29 | |

| I feel better knowing I don't smoke regular cigarettes | 6.16 | |

| It makes me feel happy that vaping is helping me not to smoke cigarettes | 6.09 | |

| Vaping leaves no bad aftertaste | 5.93 | |

| I can choose how much nicotine I inhale | 5.86 | |

| Every time I vape instead of smoking, I feel I have achieved something by avoiding tobacco |

5.81 | |

| I have no need for nasty cigarettes | 5.79 | |

| I love myself for being a non-smoker | 5.72 | |

| I have control of the amount I inhale | 5.70 | |

| Food actually tastes better now | 5.69 | |

| Vaping has gotten me 100% off of cigarettes and my family doesn't nag me anymore |

5.67 | |

| My family is happier that I am healthier | 5.65 | |

| Vaping makes me feel accomplished because I quit smoking cigarette | 5.60 | |

| I can use this in place regular cigarettes and still have the taste | 5.60 | |

| I don't miss smoking at all and when I can't vape | 5.44 | |

| I can go another hour without the 'real deal' | 5.19 | |

| I like being able to enjoy pleasant flavors without the consequence of calories | 5.14 | |

| I don't have withdrawals from not vaping consistently | 5.09 | |

| I don't feel addicted to vaping | 4.74 | |

| I crave less sweets | 4.30 | |

| Vaping curbs my appetite | 4.02 | |

| Social/Environment Effects | ||

| Convenience | 5.36 | |

| My home, car, and workspace doesn't smell like smoke | 6.28 | |

| I like that I can vape indoors and in my car | 6.02 | |

| I no longer worry about littering the environment with ashes and cigarette butts | 5.77 | |

| It delights me that I can vape any place and time | 5.60 | |

| Vaping saves me trips to the store instead of buying one pack of cigarettes at a time like I used to do |

5.33 | |

| It does not bother me as much when I am unable to vape due to environment | 5.28 | |

| Vaping is saving me lots of money | 5.26 | |

| Feel more comfortable vaping around pets | 5.21 | |

| Flavors of fruit and desserts steer me from the scent and taste of tobacco | 5.14 | |

| I can take a puff in a location I'm not supposed to without anyone knowing | 5.07 | |

| I don't have to worry about my lighters | 4.84 | |

| I feel comfortable vaping around children and not worried about hurting their health |

4.56 | |

| Social Impacts | 4.93 | |

| I can vape inside without any negative effects like smell or other people complaining |

5.91 | |

| Vaping is more socially acceptable | 5.74 | |

| I am glad my family is approving of me using the e-cigarette | 5.51 | |

| Not having to step outside and leave a conversation midway | 5.42 | |

| Love that when I go to kiss my boyfriend/girlfriend we don't smell or taste bad | 5.40 | |

| Friends bug me less about quitting when vaping vs cigarettes | 5.37 | |

| Less negative stigma than smoking | 5.33 | |

| I am glad I can smoke without being put into the 'smoker crowd' category | 5.09 | |

| If people are smoking you can join them with your vape and not feel like a 3rd wheel in a smokers group |

5.00 | |

| Fitting in with non-smoking groups by choosing a healthy alternative | 4.98 | |

| I get lots of compliments and people telling me how glad they are I quit smoking |

4.86 | |

| I get more positive attention from men/women who don't like the smell of cigarettes |

4.79 | |

| I spend more time with family because they [ECIGs] are odorless | 4.77 | |

| People are friendly when your vaping | 4.42 | |

| I felt like I was 'getting over' on the anti-tobacco crowd in society | 4.19 | |

| Vaping is very fun to show friends | 4.09 | |

| It's a good way to make friends | 4.07 | |

| Vaping is an upscale way of smoking | 3.70 | |

Pleasurable Effects

Therapeutic/Affect Regulation

The 17 statements in this cluster had a mean rating of 5.09 (SD = 0.55) and generally described feelings of calm, relaxation, satisfaction, and relief as a result of using ECIGs. Many of the statements in the cluster described negative reinforcement in which ECIG use alleviated undesired affect and sensations. For example, participants perceived that ECIG use satisfied cravings, helped to reduce stress, were calming, and provided instant relief. One statement indicated specifically that “vaping is a great form of therapy.”

High/Euphoria

The 17 statements in this cluster (M = 4.69, SD = 0.68) described positive physiological outcomes related to ECIG use, such as feelings of elation. In contrast to the statements in the Therapeutic/Affect Regulation cluster, the High/Euphoria cluster statements described positive ECIG use outcomes associated with positive affect and sensations rather than removing negative affect and sensations. For example, some statements described that ECIGs were enjoyable, helped improve concentration, and provided a head rush or buzz. Other statements also described more general positive experiences (e.g., “Vaping completes me” and “I have felt empowered on many different levels”).

Sensation Enjoyment

The 15 statements in this cluster (M = 4.83, SD = 0.82) described different aspects of ECIG use that appeal to multiple senses (i.e., taste, smell, sight), as summarized in the statement: “The sensation of the vapor and the good flavors is pleasant.” Many of the statements in this cluster described the taste of the flavors. For instance, ECIG users reported “vaping tastes delicious” and that it is enjoyable to be able to “taste different types of e-liquids.” In addition to describing that ECIG vapor smells pleasant, some statements described visual appeals of ECIGs with statements specifying that ECIGs were “beautiful works of art” to look at as well as describing “tricks” as a fun part of ECIG use.

Personal Changes and Improvements

Perceived Health Effects

This cluster had the most number of statements (n = 23) and the highest mean statement rating (M = 5.66, SD = 0.46). The statements in this cluster described the perceived positive effects ECIG use had on the body, especially compared to cigarette smoking. These statements seemed to reflect two categories: perceptions of ECIG use improving health and ECIG use not causing the same negative health effects as cigarette smoking. For example, ECIG users perceived that ECIG use allowed them to breathe better, run, and improved their sense of smell (i.e., health improvements). Participants also stated that ECIG use was enjoyable because it did not harm the body, did not cause teeth yellowing, did not cause the throat or lungs to hurt, and did not cause headaches.

Benefits of Decreased Cigarette Use

The 21 statements in this cluster (M = 5.50, SD = 0.87) described unique benefits of ECIG use that seemed to be related directly to decreased cigarette use. While many of the statements in this cluster seemed to be related to the same general construct as the statements in the Perceived Health Effects cluster, the Benefits of Decreased Cigarette Use statements appeared to make more explicit connections to the advantages of ECIG use as they related to cigarette smoking and the positive outcomes that were not completely related to health. For example, participants stated that ECIGs helped to decrease cigarette smoking: “Vaping has cut down on my smoking dramatically.” “Other statements described perceptions of control and decreased addiction associated with vaping: “I have control of the amount I inhale,” and “I can choose how much nicotine I inhale.” Several statements identified ECIG use outcomes related to taste and food: “I crave less sweets,” and “I like being able to enjoy pleasant flavors without the consequence of calories.”

Social/Environment Effects

Convenience

The 12 statements in this cluster (M = 5.36, SD = 0.47) described outcomes of ECIG use that make ECIGs more convenient to use, especially compared to cigarettes. For instance, this cluster includes themes of freedom to use ECIGs in many locations (e.g., “It delights me that I can vape any place and time”), cost (e.g., “Vaping is saving me lots of money”), and decreased inconveniences (e.g., “Vaping saves me trips to the store…”). Some statements also indicated a perception of ECIG use being associated with decreased negative impacts on the environment and others: “I no longer worry about littering the environment…” and “I feel comfortable vaping around children and not worried about hurting their health.”

Social Impacts

This cluster of 18 statements (M = 4.93, SD = 0.61) described ways in which ECIG use affected social interactions positively. Several statements identified specifically the positive effect of the lack of bad smell associated with ECIG use: “I can vape inside without any negative effects like smell or other people complaining,” “Love that when I go to kiss my boyfriend/girlfriend we don’t smell or taste bad,” and “I spend more time with family because they [ECIGs] are odorless.” Other statements indicated vaping can improve direct interactions with others: “I get more positive attention from [others],” “People are friendly when you are vaping,” and “It’s a good way to make friends.” Finally, statements in the social impacts cluster also implied ECIG use is perceived with less negative stigma than cigarette smoking: “Vaping is more socially acceptable,” and “Less negative stigma than smoking.”

Cluster Rating Comparisons

Mean cluster ratings were similar across all clusters (mean cluster ratings range = 4.69 - 5.66 on the 7-point rating scale indicating participants on average reported that the statements within each cluster were positive, enjoyable, and exciting outcomes associated with ECIG use. The highest rated cluster was the Perceived Health Effects (M = 5.66, SD = 0.46) cluster while the lowest rated clusters were the Social Impacts, Sensation Enjoyment, and High/Euphoria clusters (Ms = 4.69 - 4.93, SDs = 0.61 - 0.82). Subgroup analyses from planned contrasts indicated men and women differed on ratings of five of the seven clusters: Perceived Health Effects, Convenience, Social Impacts, Therapeutic/Affect Regulation, and High/Euphoria (ps < 0.05) with females rating each of these clusters higher than males (mean cluster rating differences = 0.32 - 0.82). Participants between the ages of 18 and 25 rated the Social Impacts cluster higher (M = 5.37, SD = 0.59) compared to participants over the age of 25 (M = 4.83, SD = 0.66; p < 0.02).

Participants who did not report smoking >100 cigarettes in their life rated the Perceived Health Effects and Social Impacts clusters higher than participants who reported smoking >100 cigarettes in their life (ps < 0.05, mean cluster rating differences = 0.40). Participants who reported non-daily ECIG use rated the High/Euphoria cluster (M = 5.07, SD = 0.42) higher than daily ECIG users (M = 4.5, SD = 0.86; p < 0.05). Past-30 day cigarette smokers rated four of the clusters higher than those who did not report cigarette smoking in the past 30 days: Convenience, Social Impacts, Therapeutic/Affect Regulation, and High/Euphoria (ps < 0.05). Device type was also associated with different mean cluster ratings with those who reported using early generation “cig-alike” devices rating the Social Impacts, Therapeutic/Affect Regulation, and High/Euphoria clusters higher than those who reported using later generation vape pens, box mods, or rebuildable/mechanical mods (ps < 0.02). No other significant differences were found in planned contrasts of cluster ratings based on ECIG use history, flavor preferences, or social use patterns.

Discussion

The results of this study are consistent with prior studies that show that ECIG users associate many positive outcomes with ECIG use. Using CM, this study identified seven thematic clusters grouped under three broad constructs all related to positive outcomes adult ECIG users associate with ECIG use. Participant responses indicated that ECIG users perceived that ECIG use can provide feelings of euphoria and relaxation (i.e., Physical Effects), improve health and alleviate many negative outcomes associated with cigarette smoking (i.e., Personal Changes and Improvements), and can improve social interactions and interactions with one’s environment (i.e., Social/Environmental Effects). Overall, participants rated highly all clusters of statements, thus indicating that all clusters were relevant positive outcomes associated with ECIG use. Similarly, subgroups of the sample rated the statements within clusters similarly, however, female participants rated statements in all but two clusters higher than males. Participants who had not smoked 100 cigarettes in their lifetime rated statements related to health impacts and social impacts higher than those who had smoked >100 cigarettes in their lifetime, and non-daily ECIG users rated statements related to positive physical effects (e.g., high, euphoria) higher than daily ECIG users. There were also differences in cluster ratings based on ECIG device type and past-30 day cigarette smoking status. Because of the small sample size of the current study, it is difficult to speculate what these differences imply. Therefore, future research should continue to examine how ECIG user subgroups’ ECIG outcome expectancies differ and if these differences are associated with greater or less likelihood of ECIG use. These subgroup variations may also help inform interventions that target specific populations as well as the population as a whole.

While broad conclusions about the findings of the current study may be useful for understanding ECIG use, context is necessary to understand fully the potential implications of the study findings. First, ECIGs appear to provide users with many of the same positive outcomes associated with traditional forms of tobacco (e.g., relaxation, feelings of euphoria, stress relief, appetite suppression; Brandon & Baker, 1991). Moreover, the current results are consistent with others (Pokhrel et al., 2014) indicating that affect regulation (stress relief, relaxation) was an important ECIG outcome expectation. However, this study found that ECIGs are perceived to provide unique benefits that are not associated with traditional forms of tobacco (e.g., decreased stigma, ability to use anywhere and anytime), which is consistent with expectancies in other studies that have examined ECIG outcome expectancies and reasons for use (Harrel et al., 2015, Pokhrel et al., 2014; Soule et al., 2016c). For some cigarette smokers, these positive outcomes may be strong enough to promote complete replacement of cigarettes with ECIGs, but future studies are needed to investigate factors that influence the likelihood of this switching behavior.

Though this study is cross sectional and smoking status was self-reported, approximately 40% of the sample reported no cigarette smoking during the 30 days prior to completing the study. However, approximately 45% of the sample reported both ECIG and cigarette smoking past 30 days, and 15% of the sample were past-30 day ECIG users who had smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Though participants who had smoked less than 100 lifetime cigarettes rated several clusters higher, current, former, and non-lifetime cigarette smokers all rated the positive ECIG use outcomes highly in the current study. This supports the idea that the potential positive outcomes associated with ECIG use may appeal to current, former, and never cigarette smokers. Further research is needed to examine if these groups (i.e., former smoker ECIG users, ECIG and cigarette dual users, non-former smoker ECIG users) differ regarding their behaviors and perceptions associated with ECIGs. Additionally, past-30 day cigarette smoking was associated with higher ratings of certain clusters compared to those who did not report past-30 day cigarette smoking. This finding would appear to be contradictory as one might expect dual users of cigarettes and ECIGs rate ECIG outcome expectations higher than non-dual users to them transition to exclusive ECIG use. Perhaps these data indicate ECIGs may represent a complement to cigarette smoking for some cigarette smokers, rather than a replacement. Future research is needed to understand this phenomenon.

This study had several limitations. The study sample size was small which could limit the generalizability of the findings. However, the sample was recruited from eight states across the U.S. from each of the four census tract regions. Approximately 62% of the sample were male and gender representation improved as compared to prior studies (Soule et al., 2015; Soule et al., 2016). Additionally, based on U.S. census data (United States Census Bureau, 2016) and the most recent race/ethnicity data on adult ECIG use (Shoenborn & Gindi, 2015) and the sample from this study did not differ appreciably from the race/ethnicity profile of U.S. adult current ECIG users. However, future studies that focus on ECIG use characteristics among subgroups of the population that have the highest ECIG use rates, such as American Indians and Alaskan Natives (Schoenborn & Gindi, 2015), may help explain differences in population subgroup prevalence rates. The design of the study did not allow for the identification of which statements were generated from each participant or subgroups of the sample. While these data may have been useful, analysis of participants’ statement ratings indicated that in general, participants rated the statements similarly indicating the clusters were meaningful for all subgroups of the sample. The study also had several strengths. The clusters identified in this study were similar to those identified in a previous CM study examining reasons for ECIG use (Soule et al., 2016c). The similarity of the findings from these two studies examining related research questions demonstrates the reliability of the constructs identified and the CM method used to identify these constructs. This study builds on two prior studies (Harrell et al., 2015b; Pokhrel et al., 2014) and is also one of the first to conduct an in-depth examination of the positive outcomes that ECIG users associate with ECIG use. These data will help health professionals and regulators better understand the factors that may influence ECIG use and continued use.

Though public health experts continue to debate whether ECIGs represent a viable option for smoking cessation, a harm reduction strategy, or a potential setback in tobacco use prevention, ECIG use continues to gain popularity with cigarette smokers as well as non-smokers. There is great interest in better understanding the initiation of ECIGs, dual use of cigarettes and ECIGs, and complete switching from cigarettes to ECIGs. The results from this mixed-methods study can be used to develop an ECIG use expectancy measure which could be used to assess and impact important health outcomes. For example, larger studies that examine positive ECIG use outcome expectancies identified in the current study may allow for a more in-depth examination of the subgroup differences found in the current study. Additionally, an ECIG use expectancy measure could aid health professionals in predicting ECIG use susceptibility and future ECIG use. If certain expectancies are associated ECIG use uptake among at risk populations, such as youth, prevention efforts could focus on addressing these types of beliefs among youth who may be susceptible for ECIG use perhaps by helping youth find alternative positive behaviors that could take the place of ECIG use. Similarly, future studies examining ECIG outcome expectancies may aid in understanding other aspects of ECIG use behavior, such as why some ECIG users continue to use ECIGs while others do not. That is, are there certain ECIG use outcome expectancies that are more important for ECIG use initiation and maintenance? As ECIG products continue to evolve and gain popularity, it will be important to examine ECIG use perceptions in order to better understand ECIG use behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P50DA036105 and the Center for Tobacco Products of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration. The results of this study were presented at the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Europe Conference in Prague, Czech Republic.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared.

Contributor Information

Eric K. Soule, Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University

Sarah F. Maloney, Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University

Mignonne C. Guy, Department of African American Studies, Virginia Commonwealth University

Thomas Eissenberg, Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Pebbles Fagan, Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

References

- Adkison SE, O'Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, Hyland A, Borland R, Yong HH, Fong GT. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: international tobacco control four-country survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(3):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018. http://dx.doi.10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola RA, Neff LJ, Kennedy SM, Holder-Hayes E, Jones CD. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2013. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63(45):1021–1026. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Apelberg BR, Caraballo RS. Tobacco use among middle and high school students – United States, 2011-2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortalilty Weekly Report. 2015;64(14):381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: 1986. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett TE, Lorenzo FE, Soule EK. Hookah smoking outcome expectations among young adults. Substance Use and Misuse. 2016 doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1214152. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Baker TB. The smoking consequences questionnaire: the subjective expected utility of smoking in college students. Psychological Assessment. 1991;3(3):484–491. [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Haardoerfer R, Escoffery C, Zheng P, Kegler M. Cigarette users' interest in using or switching to electronic nicotine delivery systems for smokeless tobacco for harm reduction, cessation, or novelty: a cross-sectional survey of US adults. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2015;17(2):245–255. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu103. http://dx.doi.10.1093/ntr/ntu103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, West R, Beard E, Michie S, Shahab L, McNeill A. Prevalence and characteristics of e-cigarette users in Great Britain: findings from a general population survey of smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(6):1120–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.03.009. http://dx.doi.10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Notes from the field: electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students – United States, 2011–2012. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013a;62(35):729–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Tobacco product use among middle and high school students–United States, 2011 and 2012. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013b;62(45):893–897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Edwards DA. Four pathways to young-adult smoking status: adolescent social-psychological antecedents in a midwestern community sample. Health Psychology. 1991;10(6):409–418. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.6.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Bernhardt AM, Stevens M. Positive and negative outcome expectations of smoking: implications for prevention. Preventive Medicine. 1999;29(6):460–465. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison ML. Multidimensional scaling. John Wiley and Sons; New York, NY: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Doran N, Schweizer CA, Myers MG. Do expectancies for reinforcement from smoking change after smoking initiation? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25(1):101–107. doi: 10.1037/a0020361. http://dx.doi.10.1037/a0020361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health edducation: Theory, research, and practice. 4th Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Goniewicz ML, Lingas EO, Hajek P. Patterns of electronic cigarette use and user beliefs about their safety and benefits: an internet survey. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2013;32(2):133–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00512.x. http://dx.doi.10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA. Dynamic self-efficacy and outcome expectancies: prediction of smoking lapse and relapse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(4):661–675. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell PT, Marquinez NS, Correa JB, Meltzer LR, Unrod M, Sutton SK, Brandon TH. Expectancies for cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and nicotine replacement therapies among e-cigarette users (aka vapers) Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2015a;17(2):193–200. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu149. http://dx.doi.10.1093/ntr/ntu149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell PT, Simmons VN, Pineiro B, Correa JB, Menzie NS, Meltzer LR, Brandon TH. E-cigarettes and expectancies: why do some users keep smoking? Addiction. 2015b;110(11):1833–1843. doi: 10.1111/add.13043. http://dx.doi.10.1111/add.13043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks PS, Cases MG, Thorne CB, Cheong J, Harrington KF, Kohler CL, Bailey WC. Hospitalized smokers’ expectancies for electronic cigarettes versus tobacco cigarettes. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;41:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.031. http://dx.doi.10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel K, Hoving C, Nagelhout GE, de Vries H, van den Putte B, Candel MJ, Willemsen MC. Prevalence and reasons for use of electronic cigarettes among smokers: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Netherlands Survey. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2015;26(6):601–608. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.12.009. http://dx.doi.10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries SK, Catley D, Okuyemi KS, Nazir N, McCarter KS, Grobe JE, Ahluwaalia JS. Use of a brief Smoking Consequences Questionnaire for Adults (SCQ-A) in African American smokers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(1):74–77. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano LM, Brandon TH. Smokers’ expectancies for nicotine replacement therapy vs. cigarettes. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6(3):569–574. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001696574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadimpati S, Nolan M, Warner DO. Attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding electronic nicotine delivery systems in patients scheduled for elective surgery. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.11.005. http://dx.doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane M, Trochim WMK. Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- King BA, Patel RK, Nguyen K, Dube SR. Trends in awareness and use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010–2013. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2015;17(2):219–227. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu191. http://dx.doi.10.1093/ntr/ntu191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralikova E, Novak J, West O, Kmetova A, Hajek P. Do e-cigarettes have the potential to compete with conventional cigarettes?: a survey of conventional cigarette smokers' experiences with e-cigarettes. Chest. 2013;144(5):1609–1614. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2842. http://dx.doi.10.1378/chest.12-2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal JB. Multimensional scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to nonmetric hypothesis. Psychometrika. 1964;29(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal JB, Wish M. Multidimensional scaling. Sage Publications; Beverly Hills, CA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Newcombe R, Walton D. The prevalence, correlates and reasons for using electronic cigarettes among New Zealand adults. Addictive Behaviors. 45:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.006. http://dx.doi.10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark KS, Farquhar B, Chisolm MS, Coleman-Cowger VH, Terplan M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of electronic cigarette use among pregnant women. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2015;9(4):266–272. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000128. http://dx.doi.10.1097/ADM.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen RC, Gottlieb MA, Shaefer RM, Winickoff JP, Klein JD. Trends in electronic cigarette use among U.S. adults: use is increasing in both smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2014;17(10):1195–1202. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu213. http://dx.doi.10.1093/ntr/ntu213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper JK, Ribisl KM, Emery SL, Brewer NT. Reasons for starting and stopping electronic cigarette use. The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014;11(10):10345–10361. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111010345. http://dx.doi.10.3390/ijerph111010345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Harrell PT, Hendricks PS, O'Grady KE, Pickworth WB, Vocci FJ. Electronic cigarettes in adults in outpatient substance use treatment: Awareness, perceptions, use, and reasons for use. The American Journal on Addictions. 2015;24(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12206. http://dx.doi.10.1111/ajad.12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro B, Correa JB, Simmons VN, Harrell PT, Menzie NS, Unrod M, Brandon TH. Gender differences in use and expectancies of e-cigarettes: online survey results. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;52:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.006. http://dx.doi.10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Little MA, Fagan P, Muranaka N, Herzog TA. Electronic cigarette use outcome expectancies among college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(6):1062–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.014. http://dx.doi.10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, Pearson J, Xiao H, Stalgaitis C, Vallone D. Prevalence, harm perceptions, and reasons for using noncombustible tobacco products among current and former smokers. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(8):1437–1444. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301804. http://dx.doi.10.2105/AJPH.2013.301804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas SR, Kane M. Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2012;35:236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.10.003. http://dx.doi.10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S, Kim MP. The method of sorting as a data gathering procedure in multivariate research. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1975;10(4):489–502. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr1004_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA, Gindi RM. Electronic cigarette use among adults: United States, 2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;217:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Homa DM, King BA. Tobacco use among middle and high school students - United States, 2011-2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;2016;65(14):361–367. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soule EK, Lopez AA, Guy MG, Cobb CO. Reasons for using flavored liquids among electronic cigarettes users: a concept mapping study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016a;166:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soule EK, Nasim A, Rosas SR. Adverse effects of electronic cigarette use: a concept mapping study. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2016b;18(5):678–685. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv246. http://dx.doi.10.1093/ntr/ntv246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soule EK, Rosas S, Nasim A. Reasons for electronic cigarette use beyond cigarette smoking cessation: a concept mapping approach. Addictive Behaviors. 2016c;56:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.01.008. http://dx.doi.10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Caviness CM, Grimone K, Audet D, Borges A, Anderson BJ. E-cigarette knowledge, attitudes, and use in opioid dependent smokers. Journal Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;52:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.11.002. http://dx.doi.10.1016/j.jsat.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trochim WMK. An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1989;12:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/RHI125215/00.

- Wahl SK, Turner LR, Mermelstein RJ, Flay BR. Adolescents’ smoking expectancies: psychometric properties and prediction of behavior change. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2005;7(4):613–623. doi: 10.1080/14622200500185579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JH. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1963;58(301):236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Weller SC, Romney AK. Systematic data collection. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1988. [Google Scholar]