Abstract

BACKGROUND:

There is currently insufficient evidence regarding the prognosis of multifetal pregnancy following elective fetal reduction to twin or singleton pregnancy. We compared perinatal outcomes in pregnancies with and without fetal reduction.

METHODS:

We used data on all stillbirths and live births in British Columbia, Canada, from 2009 to 2013. We compared outcomes of multifetal pregnancies with fetal reduction (to twin or singleton pregnancy) with outcomes of pregnancies without fetal reduction. The primary outcome was a composite of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death. Other outcomes studied included preterm birth, low birth weight and small-for-gestational-age live birth.

RESULTS:

The rate of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death did not differ significantly between pregnancies reduced to twins and unreduced triplet pregnancies (adjusted rate ratio 0.50, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.24–1.07) or between pregnancies reduced to singletons and unreduced twin pregnancies (adjusted rate ratio 1.57, 95% CI 0.74–3.33). The rate was significantly lower in the fetal reduction group reduced to twins versus unreduced triplet pregnancies when we restricted the analysis to pregnancies conceived following the use of assisted reproduction technologies (adjusted rate ratio 0.35, 95% CI 0.18–0.67). The rates of preterm birth, very preterm birth, low birth weight and very low birth weight were significantly lower among pregnancies reduced to twins than among unreduced triplet pregnancies. Compared with unreduced twin pregnancies, pregnancies reduced to singletons had lower rates of preterm birth and low birth weight.

INTERPRETATION:

Fetal reduction to twins and singletons was not associated with a decreased risk of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death. However, such fetal reduction was associated with substantial improvements in several other perinatal outcomes, such as preterm birth and low birth weight. Clinicians discussing the risks associated with multifetal pregnancy should counsel parents on the potential risks and benefits of fetal reduction.

There has been a rise in rates of multiple births in many high-income countries, with a doubling of twin births and a threefold increase in triplet births in recent decades.1,2 In Canada, rates of triplet and higher order multiple births have increased from 52.2 to 83.5 per 100 000 live births between 1991 and 2009.1 This change has occurred primarily because of increases in maternal age at delivery, and especially because of increased use of fertility treatments such as ovulation induction and related assisted reproductive technologies.3 Despite the advances in clinical care that have improved perinatal outcomes for multifetal gestation,4 twin pregnancies, and especially triplet and higher order multiple pregnancies, continue to experience elevated risks of adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes.1,2,5,6

Although it is accepted that elective fetal reduction of high-order multiple pregnancy with 4 or more fetuses substantially improves maternal and perinatal outcomes, fetal reduction is sometimes viewed as a social rather than a medical issue.2,7,8 Furthermore, studies comparing triplet pregnancies reduced to twins and triplet pregnancies managed conservatively have reported conflicting results: some have shown no difference in gestational age at delivery or in neonatal outcomes,7,9 whereas others have reported substantial improvements in perinatal outcomes.2,10,11 Perhaps the most provocative unanswered question pertains to fetal reduction in twin pregnancies. We therefore compared perinatal outcomes in multifetal pregnancies with fetal reduction (to twin or singleton pregnancy) and without fetal reduction.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a retrospective cohort study including all births to women who underwent elective fetal reduction to a twin or a singleton pregnancy in British Columbia, Canada, from April 2009 to December 2013. The comparison group consisted of all births between April 2009 and December 2013 to women with triplet, twin or singleton pregnancies who did not undergo elective fetal reduction. Information on these births was obtained from the British Columbia Perinatal Data Registry. This population-based, clinically focused database includes abstracted medical records with details regarding maternal characteristics, and prenatal, labour, delivery and neonatal events from more than 99% of live births and stillbirths (including home births) in the province.12 Diagnoses and interventions in this database are coded with the use of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Canadian modification (ICD-10-CA) and the Canadian Classification of Interventions, respectively. Data quality is continually assessed by logic and consistency checks, and the information in the database has been validated13 and used extensively for health planning and research purposes.13–17

Beginning in 2009, fetal reduction procedures have been identified using the ICD-10-CA code for “continuing pregnancy after selective fetal reduction of one fetus or more” (code O31.12). We used this code to identify women who underwent a fetal reduction. In addition, we reviewed the medical charts of women undergoing fetal reduction between 2009 and 2013 at the BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre (the institution where most fetal reductions in the province are performed).

Outcome measures

The primary study outcome was a composite of stillbirth, in-hospital neonatal death and serious neonatal morbidity. Serious neonatal morbidity included any of the following: a 5-minute Apgar score of 3 or less, neonatal convulsions, use of assisted ventilation, neonatal sepsis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotizing enterocolitis, retinopathy of prematurity, grade 3 or 4 intraventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia and neonatal encephalopathy.18,19 Other outcomes studied included preterm birth (< 37 completed weeks’ gestation), very preterm birth (< 32 completed weeks’ gestation), small-for-gestational-age live birth (< 10th centile),20 low birth weight (< 2500 g), very low birth weight (< 1500 g) and low 5-minute Apgar score (≤ 7). Gestational age at delivery was determined with the use of a hierarchical algorithm based on the date of last menstrual period, earliest ultrasound before 20 weeks’ gestation, pediatric examination of the newborn and other documentation in the medical charts.

Statistical analysis

We compared differences in maternal characteristics between women who underwent fetal reduction and those who did not. We compared multifetal pregnancies reduced to twin pregnancies with unreduced triplet pregnancies, and pregnancies reduced to singleton pregnancies with unreduced twin pregnancies. We used multivariable log-linear regression models with robust variance estimates to determine the association between perinatal outcomes and fetal reduction among pregnancies in the entire cohort and among pregnancies conceived following the use of assisted reproductive technologies. Contrasts of interest were quantified with adjusted rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), with adjustment for potential confounders. The full models included maternal age at delivery, parity, pre-pregnancy weight, socioeconomic status (based on neighbourhood income data obtained from the 2006 Canada census), receipt of assisted reproduction and infant sex.

We conducted supplementary analyses comparing pregnancies reduced to twin pregnancies with unreduced twin pregnancies; pregnancies reduced to twin pregnancies with pregnancies reduced to singleton pregnancies; and pregnancies reduced to singleton pregnancies with unreduced singleton pregnancies.

Analyses were performed with the use of SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Ethics approval

The University of British Columbia’s Clinical Research Ethics Board approved the study.

Results

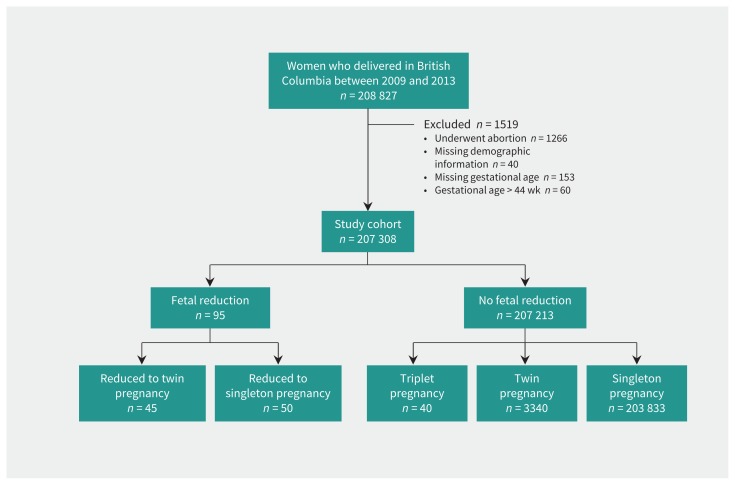

Among 208 827 women who delivered in British Columbia between 2009 and 2013, 95 (0.04%) underwent fetal reduction. Of these, 45 women delivered twins and 50 delivered singletons (Figure 1). Women who had a fetal reduction were more likely to be older and have a higher socioeconomic status than those without a fetal reduction(Table 1). Maternal pre-pregnancy weight and parity were comparable between the 2 groups, but women who had a fetal reduction to twins had higher rates of gestational diabetes and hypertension in pregnancy than women who did not have fetal reduction. Women who had a fetal reduction were substantially more likely to have used assisted reproductive technologies than were those who did not undergo fetal reduction (> 75% v. 3.3%). Our review of charts from the BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre showed that 44% of the fetal reductions during the study period were from triplets to twins, 46% were from twins to singletons, 4% were from triplets to singletons, and 6% were from quadruplets to twins.

Figure 1:

Selection of study cohort.

Table 1:

Maternal demographic and clinical characteristics among pregnancies with and without fetal reduction

| Characteristic | Fetal reduction; no. (%) of pregnancies | No fetal reduction; no. (%) of pregnancies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Reduced to twin pregnancy n = 45 |

Reduced to singleton pregnancy n = 50 |

Triplet pregnancy n = 40 |

Twin pregnancy n = 3340 |

Singleton pregnancy n = 203 833 |

|

| Maternal age at delivery, yr | |||||

|

| |||||

| < 35 | 17 (37.8) | 17 (34.0) | 23 (57.5) | 2123 (63.6) | 156 660 (76.9) |

|

| |||||

| 35–39 | 20 (44.4) | 17 (34.0) | > 13* (> 30.0) | 898 (26.9) | 38 240 (18.8) |

|

| |||||

| ≥ 40 | 8 (17.8) | 16 (32.0) | < 5* (< 12.5) | 319 (9.6) | 8933 (4.4) |

|

| |||||

| Parity | |||||

|

| |||||

| Nulliparous | 30 (66.7) | 23 (46.0) | 26 (65.0) | 1729 (51.8) | 94 879 (46.6) |

|

| |||||

| Multiparous | 15 (33.3) | 27 (54.0) | 14 (35.0) | 1611 (48.2) | 108 954 (53.5) |

|

| |||||

| Pre-pregnancy weight, kg | n = 38 | n = 42 | n = 35 | n = 2579 | n = 164 757 |

|

| |||||

| < 60 | 14 (36.8) | 14 (33.3) | 8 (22.9) | 891 (34.5) | 66 216 (40.2) |

|

| |||||

| 60–69 | 8 (21.1) | 12 (28.6) | 11 (31.4) | 780 (30.2) | 47 195 (28.6) |

|

| |||||

| 70–79 | 8 (21.1) | 8 (19.0) | 10 (28.6) | 430 (16.7) | 25 983 (15.8) |

|

| |||||

| ≥ 80 | 8 (21.1) | 8 (19.0) | 6 (17.1) | 478 (18.5) | 25 363 (15.4) |

|

| |||||

| Socioeconomic status | n = 44 | n = 48 | n = 3293 | n = 200 729 | |

|

| |||||

| Lowest | 18 (40.9) | 11 (22.9) | 15 (37.5) | 1264 (38.4) | 85 478 (42.6) |

|

| |||||

| Middle | 16 (36.4) | 20 (41.7) | 14 (35.0) | 1411 (42.8) | 82 802 (41.3) |

|

| |||||

| Highest | 10 (22.7) | 17 (35.4) | 11 (27.5) | 618 (18.8) | 32 449 (16.2) |

|

| |||||

| Gestational diabetes | |||||

|

| |||||

| No | 32 (71.1) | 42 (84.0) | 32 (80.0) | 2882 (86.3) | 183 667 (90.1) |

|

| |||||

| Yes | 13 (28.9) | 8 (16.0) | 8 (20.0) | 458 (13.7) | 20 166 (9.9) |

|

| |||||

| Hypertension in pregnancy | |||||

|

| |||||

| No | 39 (86.7) | 50 (100.0) | > 35* (> 87.5) | 3119 (93.4) | 199 378 (97.8) |

|

| |||||

| Yes | 6 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | < 5* (< 12.5) | 221 (6.6) | 4455 (2.2) |

|

| |||||

| Mode of delivery | n = 3329 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Cesarean | 31 (68.9) | 21 (42.0) | > 35* (> 87.5) | 2341 (70.2) | 61 933 (30.4) |

|

| |||||

| Vaginal | 14 (31.1) | 29 (58.0) | < 5* (< 12.5) | 988 (29.8) | 141 900 (69.6) |

|

| |||||

| Use of assisted reproductive technology | |||||

|

| |||||

| No | < 5* (< 11.1) | 18 (36.0) | 14 (35.0) | 2153 (64.5) | 198 195 (97.2) |

|

| |||||

| Yes | > 40* (> 88.9) | 32 (64.0) | 26 (65.0) | 1187 (35.5) | 5638 (2.8) |

Exact count suppressed for confidentiality reasons as a result of small numbers in this or related cells.

Characteristics of infants delivered to women with and without fetal reduction are shown in Table 2. The median gestational age at delivery was higher among pregnancies reduced to twins (36 wk, interquartile range [IQR] 33–37 wk) than among unreduced triplet pregnancies (32 wk, IQR 28–33 wk) (p < 0.001). Very preterm birth occurred less frequently among pregnancies reduced to twins (16.9%) than among unreduced triplet pregnancies (47.5%), but more frequently than among pregnancies reduced to singletons (14.0%). Preterm birth was significantly more frequent among pregnancies reduced to twins (61.8%) than among pregnancies reduced to singletons (26.0%). Pregnancies reduced to twins had significantly fewer infants with low birth weight (57.3%) compared with unreduced triplet pregnancies (96.7%). Small-for-gestational-age live birth was significantly more frequent among pregnancies reduced to twins (28.1%) than among unreduced triplet (15.0%) and unreduced twin (19.2%) pregnancies. Perinatal death occurred in 5.6% of pregnancies reduced to twins, as compared with 10.0% of unreduced triplet pregnancies and 2.4% of unreduced twin pregnancies. None of the infants from pregnancies reduced to singletons died in the neonatal period.

Table 2:

Characteristics of infants delivered to women with and without fetal reduction

| Characteristic | Fetal reduction; no. (%) of infants* | No fetal reduction; no. (%) of infants* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Reduced to twin pregnancy n = 89 |

Reduced to singleton pregnancy n = 50 |

Triplet pregnancy n = 120 |

Twin pregnancy n = 6671 |

Singleton pregnancy n = 203 833 |

|

| Female sex | 40 (44.9) | 26 (52.0) | 69 (57.5) | 3316 (49.7) | 99 192 (48.7) |

|

| |||||

| Gestational age at delivery, wk, median (IQR) | 36 (33–37) | 38 (36–39) | 32 (28–33) | 36 (34–37) | 39 (38–40) |

|

| |||||

| Very preterm (< 32 wk) | 15 (16.9) | 7 (14.0) | 57 (47.5) | 679 (10.2) | 2311 (1.1) |

|

| |||||

| Preterm (< 37 wk) | 55 (61.8) | 13 (26.0) | 120 (100.0) | 4179 (62.6) | 16 731 (8.2) |

|

| |||||

| Very low birth weight (< 1500 g) | 15 (16.9) | 5 (10.0) | 49 (40.8) | 522 (7.8) | 1561 (0.8) |

|

| |||||

| Low birth weight (< 2500 g) | 51 (57.3) | 14 (28.0) | 116 (96.7) | 3359 (50.4) | 8830 (4.3) |

|

| |||||

| Small for gestational age | 25 (28.1) | 11 (22.0) | 18 (15.0) | 1282 (19.2) | 13 265 (6.5) |

|

| |||||

| Apgar score ≤ 7 at 5 min | 12 (13.5) | 6 (12.0) | 28 (23.3) | 787 (11.8) | 8557 (4.2) |

|

| |||||

| Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 14 (15.7) | 7 (14.0) | 40 (33.3) | 612 (9.2) | 4333 (2.1) |

|

| |||||

| Perinatal death | 5 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (10.0) | 158 (2.4) | 1134 (0.6) |

Note: IQR = interquartile range.

Unless stated otherwise.

The proportion of pregnancies that had the composite outcome of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death was lower among those with fetal reduction (15.7% among pregnancies reduced to twins and 14.0% among those reduced to singletons) than among unreduced triplet pregnancies (33.3%), but higher than the proportion among unreduced twin pregnancies (9.2%) and unreduced singleton pregnancies (2.1%) (Table 2).

Table 3 shows the crude and adjusted rate ratios of perinatal outcomes among pregnancies following fetal reduction compared with pregnancies without fetal reduction. Pregnancies reduced to twins had significantly lower adjusted rates of preterm birth, very preterm birth, low birth weight and very low birth weight, and a significantly higher adjusted rate of small-for-gestational-age live birth, than unreduced triplet pregnancies. The rate of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (adjusted rate ratio 0.50, 95% CI 0.24–1.07). The rate was significantly lower among pregnancies reduced to twins when we restricted the analysis to pregnancies conceived following the use of assisted reproduction technologies, with a 65% reduction in the rate of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death associated with fetal reduction (adjusted rate ratio 0.35, 95% CI 0.18–0.67; Table 3).

Table 3:

Risk of perinatal outcomes associated with fetal reduction

| Perinatal outcome | Reduced to twin pregnancy v. unreduced triplet pregnancy | Reduced to singleton pregnancy v. unreduced twin pregnancy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| All births | ART only | All births | ART only | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Crude rate ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted rate ratio* (95% CI) | Adjusted rate ratio† (95% CI) | Crude rate ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted rate ratio* (95% CI) | Adjusted rate ratio† (95% CI) | |

| Preterm (< 37 wk) | 0.62 (0.40–0.78) | 0.66 (0.54–0.80) | 0.68 (0.56–0.84) | 0.40 (0.25–0.65) | 0.40 (0.25–0.66) | 0.42 (0.23–0.77) |

|

| ||||||

| Very preterm (< 32 wk) | 0.37 (0.18–0.76) | 0.40 (0.20–0.78) | 0.92 (0.17–0.59) | 1.24 (0.58–2.65) | 1.36 (0.64–2.92) | 1.44 (0.53–3.89) |

|

| ||||||

| Low birth weight (< 2500 g) | 0.58 (0.47–0.72) | 0.59 (0.49–0.72) | 0.58 (0.46–0.72) | 0.50 (0.30–0.81) | 0.51 (0.32–0.82) | 0.39 (0.19–0.78) |

|

| ||||||

| Very low birth weight (< 1500 g) | 0.42 (0.21–0.82) | 0.43 (0.23–0.81) | 0.39 (0.22–0.67) | 1.07 (0.42–2.76) | 1.19 (0.45–3.04) | 0.94 (0.25–3.51) |

|

| ||||||

| Small for gestational age | 1.89 (1.09–3.28) | 2.14 (1.18–3.88) | 2.29 (1.20–4.39) | 1.07 (0.62–1.87) | 1.13 (0.65–1.93) | 0.68 (0.27–1.70) |

|

| ||||||

| 5-min Apgar score ≤ 7 | 0.58 (0.28–1.19) | 0.60 (0.28–1.30) | 0.37 (0.15–0.92) | 1.06 (0.50–2.25) | 1.16 (0.55–2.46) | 1.23 (0.51–2.94) |

|

| ||||||

| Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death | 0.50 (0.24–1.02) | 0.50 (0.24–1.07) | 0.35 (0.18–0.67) | 1.39 (0.65–2.95) | 1.57 (0.74–3.33) | 1.60 (0.64–3.98) |

Note: ART = assisted reproductive technology, CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted for infant sex, maternal age, parity, pre-pregnancy weight, socioeconomic status and use of assisted reproductive technology.

Adjusted for infant sex, maternal age, parity, pre-pregnancy weight and socioeconomic status.

Pregnancies reduced to singletons had significantly lower adjusted rates of preterm birth (adjusted rate ratio 0.40, 95% CI 0.25–0.66) and low birth weight (adjusted rate ratio 0.51, 95% CI 0.32–0.82) than unreduced twin pregnancies (Table 3). Rates of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death, very preterm birth and small-for-gestational-age live birth did not differ significantly between pregnancies reduced to singletons and unreduced twin pregnancies. The findings were similar in the analysis restricted to pregnancies conceived following the use of assisted reproduction technologies (Table 3).

Supplementary analyses showed that the rates of very low birth weight and serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death were significantly higher among pregnancies reduced to twins than among unreduced twin pregnancies (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.160722/-/DC1]). Compared with pregnancies reduced to singletons, those reduced to twins had significantly higher rates of preterm birth and low birth weight, whereas the 2 groups had similar rates of small-for-gestational-age live birth and very preterm birth. Rates of all perinatal outcomes were significantly higher among pregnancies reduced to singletons than among unreduced singleton pregnancies (Appendix 1).

Interpretation

Our population-based study showed that the composite outcome of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death was not significantly lower among pregnancies reduced to twins compared with unreduced triplet pregnancies, or among pregnancies reduced to singletons compared with unreduced twin pregnancies. However, the composite outcome was significantly lower in the fetal reduction groups when we restricted the analyses to pregnancies conceived following the use of assisted reproduction technologies. Furthermore, pregnancies reduced to twins had significantly lower rates of preterm birth, very preterm birth, low birth weight and very low birth weight than unreduced triplet pregnancies. Our study also showed that the rates of preterm birth and low birth weight were lower among multifetal pregnancies reduced to singleton pregnancies than among unreduced twin pregnancies. The improved perinatal outcomes of pregnancies reduced to twins and singletons approached, but did not quite achieve, the rates of perinatal complications and death observed among unreduced twin and unreduced singleton pregnancies, respectively.

Previous studies have shown that fetal reduction to twin pregnancy was associated with reduced rates of preterm birth and low birth weight and no increase in pregnancy loss compared with unreduced triplet pregnancies.2,10,11 Pregnancy losses following fetal reduction have fallen (from previously documented rates of about 12%21) mainly because of better resolution ultrasound and increased expertise of fetal medicine specialists performing the fetal reduction.2,22,23 Rates of perinatal death in our study population were consistent with those in studies that reported a decrease in perinatal mortality after fetal reduction in triplet pregnancy from 11% to 6%,24,25 with triplet pregnancies reduced to twins doing almost as well as unreduced twin pregnancies. Nevertheless, clinicians counselling women with multifetal pregnancy should be aware of the potential for substantial parental stress resulting from fetal reduction procedures, including negative feelings such as guilt, regret and grief.26 Our finding of a higher rate of small-for-gestational-age live birth among pregnancies reduced to twins than among unreduced triplet pregnancies was likely a consequence of growth restriction increasing with advancing gestational age and the higher frequency of preterm deliveries among triplet pregnancies.27

Our results showed that fetal reduction to singleton pregnancy was associated with lower rates of preterm birth and low birth weight compared with unreduced twin pregnancies. Previous studies have reported a higher risk of miscarriage among triplet pregnancies reduced to singleton pregnancies than among triplet pregnancies reduced to twin pregnancies (6% v. 4%).7,28 However, even in these studies, the risk of preterm birth and infant morbidity was significantly reduced among the triplet pregnancies reduced to singleton pregnancies.2,8,23 Also, more recent studies showed that reduction of triplet pregnancy to singleton rather than to twin pregnancy was associated with higher rates of term delivery and improved perinatal outcomes, without a significant difference in fetal loss rates.8,23,29 The higher rate of adverse perinatal outcomes in twin pregnancies is typically a consequence of the higher incidence of preterm delivery.29,30 Clinicians report that practice changes related to fetal reduction in multifetal pregnancy are driven mainly by well-informed patients who are aware of safety and efficacy issues based on Internet publications.

In our study, rates of adverse perinatal outcomes, such as serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death, were higher among pregnancies reduced to singletons than among unreduced singleton pregnancies. This difference was likely because the multifetal pregnancies were conceived with in vitro fertilization following a diagnosis of infertility.31 Although fetal reduction to a singleton pregnancy will have beneficial effects on maternal and perinatal outcomes, the risk of mortality and morbidity will not approach that typical of an unreduced singleton pregnancy because of risks associated with infertility and related factors.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study include the use of a previously validated and clinically focused database that included information on elective fetal reduction. The population-based nature of our study is also an important strength, as are the clinically relevant contrasts that provide information for women with multifetal pregnancy contemplating different options.

The limitations of our study include the lack of detail on miscarriage before 20 weeks’ gestation and on the fetal reduction itself, including the number of fetuses reduced, the timing of fetal reduction and any clinical indications for reduction (e.g., chromosomal or anatomic abnormality). Also, we did not have information on chorionicity, although chorionicity considerations do not appear to substantially influence outcomes following fetal reduction.2 In addition, the risk of miscarriage and preterm birth does not seem to be influenced by the starting number of fetuses.23 The ICD-10-CA code used to identify fetal reductions has not been validated, although our numbers are consistent with those from the BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre, where more than 90% of such procedures in the province are performed. Residual confounding may have occurred owing to factors not available in our data sources (e.g., maternal education) or imprecise measurement of factors such as socioeconomic status.

Conclusion

Our study showed that the composite outcome of serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death was not significantly lower among multifetal pregnancies reduced to twins compared with unreduced triplet pregnancies, or among multifetal pregnancies reduced to singletons compared with unreduced twin pregnancies. However, fetal reduction to twins was associated with lower rates of preterm birth, very preterm birth, low birth weight and very low birth weight, and fetal reduction to singletons was associated with lower rates of preterm birth and low birth weight. Clinicians discussing the risks associated with multifetal pregnancy should counsel parents on the potential risks and benefits of fetal reduction.

Acknowledgements

Neda Razaz is the recipient of a Postdoctoral Fellowship award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). K.S. Joseph is supported by the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute and holds a CIHR Chair in Reproductive, Child and Youth Health Services and Policy Research.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Neda Razaz and K.S. Joseph contributed to the study concept and design. Neda Razaz drafted the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed the preliminary and final analyses, provided critical comments on the initial drafts of the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript to be published and agreed to act as guarantors of the work.

Disclaimer: This study was supported by data provided by Perinatal Services BC. The inferences, opinions and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the opinions or policies of Perinatal Services BC.

References

- 1.Fell DB, Joseph K. Temporal trends in the frequency of twins and higher-order multiple births in Canada and the United States. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wimalasundera RC. Selective reduction and termination of multiple pregnancies. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2010;15:327–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blickstein I. The worldwide impact of iatrogenic pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003;82:307–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joseph KS, Marcoux S, Ohlsson A, et al. Fetal and Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Preterm birth, stillbirth and infant mortality among triplet births in Canada, 1985–96. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2002;16:141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papageorghiou AT, Avgidou K, Bakoulas V, et al. Risks of miscarriage and early preterm birth in trichorionic triplet pregnancies with embryo reduction versus expectant management: new data and systematic review. Hum Reprod 2006; 21:1912–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avraham S, Seidman D. The multiple birth epidemic: revisited. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2012;62:386–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papageorghiou AT, Liao AW, Skentou C, et al. Trichorionic triplet pregnancies at 10–14 weeks: outcome after embryo reduction compared to expectant management. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2002;11:307–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn-Beck F, Moutel G, Weingertner AS, et al. Fetal reduction of triplet pregnancy: One or two? Prenat Diagn 2012;32:122–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Everwijn S, van de Mheen L, Ravelli A, et al. 27: Outcome after embryo reduction in triplet pregnancy compared to ongoing triplet pregnancies and primary twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206(Suppl):S19. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray SR, Norman JE. Multiple pregnancies following assisted reproductive technologies: Happy consequence or double trouble? Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2014;19:222–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van de Mheen L, Everwijn S, Haak M, et al. Outcome of multifetal pregnancy reduction in women with a dichorionic triamniotic triplet pregnancy to a singleton pregnancy: a retrospective nationwide cohort study. Fetal Diagn Ther 2016;40:94–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.British Columbia Perinatal Data Registry (2011) [data extract]. Vancouver: Perinatal Services BC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frosst G, Hutcheon J, Joseph KS, et al. Validating the British Columbia Perinatal Data Registry: a chart re-abstraction study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehrabadi A, Hutcheon JA, Lee L, et al. Trends in postpartum hemorrhage from 2000 to 2009: a population-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph KS, Kinniburgh B, Hutcheon JA, et al. Determinants of increases in stillbirth rates from 2000 to 2010. CMAJ 2013;185:E345–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutcheon JA, Lee L, Joseph KS, et al. Feasibility of implementing a standardized clinical performance indicator to evaluate the quality of obstetrical care in British Columbia. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:2688–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perinatal health report 2009/10 to 2013/14: deliveries in British Columbia. Vancouver: Perinatal Services BC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norman JE, Marlow N, Messow CM, et al. OPPTIMUM study group. Vaginal progesterone prophylaxis for preterm birth (the OPPTIMUM study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2016;387:2106–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrett JF, Hannah ME, Hutton EK, et al. Twin Birth Study Collaborative Group. A randomized trial of planned cesarean or vaginal delivery for twin pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al. Fetal/Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics 2001;108:E35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fasouliotis SJ, Schenker JG. Multifetal pregnancy reduction: a review of the world results for the period 1993–1996. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1997;75:183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans MI, Berkowitz RL, Wapner RJ, et al. Improvement in outcomes of multifetal pregnancy reduction with increased experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001; 184:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stone J, Ferrara L, Kamrath J, et al. Contemporary outcomes with the latest 1000 cases of multifetal pregnancy reduction (MPR). Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008; 199:406.e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Mheen L, Everwijn SM, Knapen MF, et al. The effectiveness of multifetal pregnancy reduction in trichorionic triplet gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014; 211:536.e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans MI, Britt DW. Fetal reduction 2008. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2008;20:386–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris RK, Kilby MD. Fetal reduction. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med 2010;20:341–3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blickstein I. Normal and abnormal growth of multiples. Semin Neonatol 2002;7: 177–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans MI, Britt DW. Multifetal pregnancy reduction: evolution of the ethical arguments. Semin Reprod Med 2010;28:295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haas J, Sasson AM, Barzilay E, et al. Perinatal outcome after fetal reduction from twin to singleton: To reduce or not to reduce? Fertil Steril 2015;103:428–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutcliffe AG, Derom C. Follow-up of twins: health, behaviour, speech, language outcomes and implications for parents. Early Hum Dev 2006;82:379–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pandey S, Shetty A, Hamilton M, et al. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in singleton pregnancies resulting from IVF/ICSI: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2012;18:485–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]