Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employees’ deviant workplace behaviors (DWB), as well as the mediating effects of psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism. A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 391 manufacturing workers in a northern city of China. Structural equation modeling was performed to test the theory-driven models. The results showed that the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employees’ DWB was mediated by organizational cynicism. Moreover, this relationship was also sequentially mediated by psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism. This research unveiled psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism as underlying mechanism that explained the link between authoritarian leadership and employees’ DWB.

Keywords: authoritarian leadership, deviant workplace behaviors, psychological contract violation, organizational cynicism, mediating effects

Introduction

Deviant workplace behaviors (DWB) are increasing dramatically, which has recently drawn extensive attention among both academicians and practitioners. Robinson and Bennett (1995) have described DWB as any voluntary acts that violate organizational norms, and thus threaten the well-being of an organization, its members, or both. A report by the US Chamber of Commerce estimates that 75% of employees steal at least once (Shulman, 2005). Moreover, DWB can be linked with adverse aspects of individuals, groups and organizations (Alias et al., 2013). For instance, unauthorized web surfing (gambling) during working hours has been estimated to cost up to £300 million loss in productivity yearly (Taylor, 2007). The majority of previous research has concentrated on the relationship between employees’ personality traits (e.g., O’Neill and Hastings, 2011; Zhang et al., 2015) and their DWB. However, very little empirical research has been done on the link between leadership style and employees’ DWB.

Leaders represent their organizations, and their actions are often related to followers’ behaviors (Aquino et al., 1999). Leadership has been conceptualized as the process of influencing the activities of an organized group towards the task accomplishment (Chemers, 1997). Among the various leadership styles, authoritarian leadership is one of the most prevalent in Chinese settings (Farh and Cheng, 2000), due to its fit with traditional cultures. Thus, authoritarian leadership has been chosen as our interested leadership construct. Authoritarian leadership is originally defined by Cheng et al. (2004) as one element of paternalistic leadership. They argue that authoritarian leadership can be conceptualized as leaders’ behaviors that assert absolute authority and control over subordinates and demand unconditional obedience. High leadership authority means low sharing of power and information with followers, as well as strong control over followers’ behaviors.

Bass (1990) has classified the main styles of leadership into transactional, transformational, empowering, and authoritarian. The first three styles could be summarized as egalitarian leadership, which stresses the notion of equal distribution of power in the community or group (Flood et al., 2000). In contrast to egalitarian leadership, authoritarian leadership places emphasis on the asymmetric power between leaders and followers, which allows leaders to put personal dominance and control over followers (Tsui et al., 2004). Moreover, authoritarian leadership differs from some other types of leadership, such as abusive supervision, which is described as supervisors’ sustained display of non-physical hostility against their subordinates (Tepper, 2000); authentic leadership, which is defined as leaders’ behaviors aiming at promoting positive psychological capacities of employees (Walumbwa et al., 2008). Compared with the above two leadership styles, the core of authoritarian leadership is asserting complete control over subordinates.

Previous research has identified some personality variables which may relate to authoritarian leadership, such as supervisors’ machiavellianism (Kiazad et al., 2010), need for personalized power (Aryee et al., 2007) and narcissism (Conger and Kanungo, 1998). Another stream of research has found that authoritarian leadership is associated with employees’ attitude, affect and behaviors, such as job dissatisfaction (Shaw, 1955), negative emotions towards supervisors (Farh et al., 2006), and extra-role behaviors (Chen et al., 2014). Although authoritarian leadership may also relate to employees’ DWB, scant attempts have been made to systematically explore the underlying mechanism behind the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employees’ DWB.

Social Exchange Theory states that the basic nature of human behaviors is a subjective interaction with others, and the development of interpersonal relationships is in accordance with the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960; Blau, 1964). According to this theory, leadership behaviors may shape the exchange relationship between leaders and followers, which might be associated with followers’ workplace behaviors. Moreover, psychological contract violation could be considered as subordinates’ unfulfilled expectation of the social exchange relationship (Brown and Moshavi, 2002). In addition, organizational cynicism is “a negative attitude toward one’s employing organization” (Dean et al., 1998). Employees with high level of organizational cynicism hold that the organization lacks integrity and that leader’s decisions are made with a self-interested drive (Andersson, 1996; Neves, 2012). From the Social Exchange Theory perspective, it is thus reasonable to infer that both psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism, which could reflect the quality of social relation between leaders and followers, may mediate the link between authoritarian leadership and employees’ DWB. Therefore, drawing on Social Exchange Theory, the current research is to investigate the relationship between authoritarian leadership and DWB. More importantly, we attempt to explain why this relationship occurs by providing important explanatory mechanism. To this end, psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism are introduced as mediators that account for the authoritarian leadership-DWB relationship.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Authoritarian Leadership and Employees’ DWB

Authoritarian leadership refers to a leader’s behaviors of implementing strong control over subordinates and requiring their unconditional obedience (Cheng et al., 2004). The main characteristic of authoritarian leadership is absolute dominance of the leaders. Authoritarian leaders are inclined to exert control by issuing rules and threatening punishment for disobedience (Aryee et al., 2007). They often apply strict discipline to subordinates’ work and exhibit their authority on decision making (Wang et al., 2013). When leaders implement their followers with an authoritarian approach, subordinates are demanded to comply with leaders’ requests without dissent and subordinates may experience negative emotions towards leaders (Farh et al., 2006). Prior research has shown that authoritarian leadership is linked with employees’ job dissatisfaction (Shaw, 1955). Furthermore, when employees are dissatisfied with their job, they may exhibit DWB like absenteeism, low performance and violence (Mount et al., 2006). Thus, it is inferred that authoritarian leadership is positively linked with employees’ DWB.

Based on Social Exchange Theory, all human behaviors are based on the reciprocal benefits in the social relationship, and the benefits exchanged are indicative of mutual support and investment in that relationship (Gouldner, 1960; Blau, 1964; Neves and Caetano, 2006). According to the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), subordinates’ attitude and behaviors are associated with leadership behaviors. When subordinates receive support or administration authority from their leaders, they are inclined to reciprocate with positive job attitude and performance. On the contrary, when subordinates are subjected to threats or intimidation from authoritarian leaders (Kiazad et al., 2010), they tend to reciprocate with negative reactions, such as DWB. Taken together, it is possible that employees under authoritarian leadership are more likely to exhibit DWB. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

-

simple H1:

Authoritarian leadership is positively related to employees’ DWB.

Mediating Role of Psychological Contract Violation

Psychological contract is an individual’s belief regarding the terms of an agreement between the individual and organization (Levinson et al., 1972; Kotter, 1973). The critical element of this concept lies in the reciprocal obligations. For instance, subordinates expect to receive rewards in exchange for their commitment and contribution to the organization. Psychological contract violation is defined as subordinates’ perception that the organization has failed to fulfill its obligations or promises (Morrison and Robinson, 1997). When the organization is unable to meet subordinates’ expectation, the psychological contract violation occurs. Authoritarian leaders often disregard followers’ suggestions and discount their contributions (Aryee et al., 2007), which makes them feel disrespected and their expectation unmet. Therefore, employees under authoritarian leadership are inclined to experience psychological contract violation.

Moreover, authoritarian leaders often control and command subordinates mainly via threats and intimidation (Kiazad et al., 2010), which could be related to employees’ negative emotions, such as anger and fear (Farh et al., 2006). These negative emotions are associated with psychological contract violation (Ortony et al., 1988; Morrison and Robinson, 1997). Thus, employees under authoritarian leadership may feel angry and fearful towards the organization and consider whether to maintain or end this organization-member relationship, and then the psychological contract is likely to be violated. Based on these previous studies, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

simple H2a:

Authoritarian leadership is positively linked with psychological contract violation.

A growing literature has suggested that psychological contract violation is linked with employees’ DWB (e.g., Restubog et al., 2007; Bordia et al., 2008). General Strain Theory (Agnew, 1992, 2006) has posited that strain occurs when negative social relationship is developed, and individuals who experience high level of accumulated strain are inclined to engage in deviant behaviors. As we know, when psychological contract is violated, employees perceive relatively lower quality relationship with their organization. Drawing from the General Strain Theory, lower quality relationship would force employees into a high-strain situation. Taking this into consideration, exhibiting DWB would be considered as a reaction to the strain. Therefore, employees with higher level of strain are more likely to show DWB (Alias et al., 2013). Based on both theoretical basis and empirical findings, it is possible that psychological contract violation is positively associated with employees’ DWB. Thus, this study puts forward the following hypothesis:

-

simple H2b:

Psychological contract violation is positively related to employees’ DWB.

The foundation of the organization-member relationship is psychological contract, which is comprised of beliefs about reciprocal obligations in this social relationship (Rousseau, 1989). When subordinates perceive that leaders fail to fulfill obligations or promises, the psychological contract violation occurs (Turnley et al., 2003). Accordingly, the research of psychological contract violation has generally taken Social Exchange Theory to understand its relationship with employees’ behaviors (Chen et al., 2004). As suggested in Social Exchange Theory (Blau, 1964; Lorinkova and Perry, 2014), leadership behaviors could shape the mutual relationship between leaders and subordinates, which may be linked with subordinates’ behaviors. Based on this theory, authoritarian leadership which makes employees’ social exchange expectation unfulfilled, may be related to employees’ higher psychological contract violation, and then employees are more likely to exert DWB. Taking these theoretical arguments and aforementioned hypotheses (H1, H2a, and H2b) into consideration, it is inferred that psychological contract violation may act as a mediator between authoritarian leadership and employees’ DWB. We propose the following hypothesis:

-

simple H2c:

Psychological contract violation mediates the link between authoritarian leadership and employees’ DWB.

Organizational Cynicism as a Mediator

Organizational cynicism is defined as “a negative attitude toward one’s employing organization, comprising three dimensions: (1) a belief that the organization lacks integrity; (2) negative affect toward the organization; and (3) tendency of showing critical behaviors towards the organization” (Dean et al., 1998). Organizational cynicism is characterized by frustration, hopelessness, contempt toward organization and lack of trust in organization (Andersson, 1996). The main reason for the link between authoritarian leadership and organizational cynicism lies in the variation of perceived organizational support. It is well acknowledged that authoritarian leaders emphasize personal dominance and control over subordinates, and they habitually get things done in their own ways (Tsui et al., 2004). Furthermore, authoritarian leaders often disregard the interests and perspectives of employees (Chan et al., 2013). Since leadership behavior operates as an important indicator of the extent of support provided by the organization (Levinson, 1965), subordinates under authoritarian leadership may feel that they get less support from the organization. Moreover, this reduction of perceived organizational support could be linked with followers’ cynical attitudes towards the organization (Leiter and Harvie, 1997; Treadway et al., 2004). Thus, it is plausible that authoritarian leadership is positively related to organizational cynicism. This study proposes the following hypothesis:

-

simple H3a:

Authoritarian leadership is positively linked with organizational cynicism.

It has been demonstrated that organizational cynicism is positively linked with employees’ DWB (e.g., James, 2005; Evans et al., 2010). Organizational cynics believe that leader is concerned only with his own self-interest, and they usually feel frustrated and being treated unfairly (Andersson, 1996). Moreover, frustration (Spector, 1997) and perceived injustice (Greenberg and Alge, 1998) are positively associated with employees’ DWB. Thus, employees with higher organizational cynicism are more likely to show DWB. Taken together, it is reasonable to infer a positive link between organizational cynicism and employees’ DWB. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

-

simple H3b:

Organizational cynicism is positively related to employees’ DWB.

According to the Social Exchange Theory (Gouldner, 1960; Blau, 1964), the behaviors of leaders, the key agents of the organization, would shape subordinates’ attitude and behaviors towards the organization. From this theory, authoritarian leadership which stresses on leaders’ dominate control over subordinates via threats and intimidation (Kiazad et al., 2010), would make subordinates feel uneasy, oppressed and generate distrust in organization (Wu et al., 2012). This sense of distrust is the main characteristic of organizational cynicism (Kanter and Mirvis, 1989; Andersson, 1996). Then, subordinates with high level of organizational cynicism may experience frustration and contempt towards organization (Andersson, 1996) and tend to engage DWB. Taking theoretical arguments and these above hypotheses (H1, H3a, and H3b) into consideration, authoritarian leaders who are arbitrary and of low trustworthiness could make employees to be cynical towards the organization, which may be related to employees’ DWB. Thus, it is plausible that organizational cynicism might account for the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employees’ DWB. The following hypothesis is tested:

-

simple H3c:

Organizational cynicism mediates the link between authoritarian leadership and employees’ DWB.

Many studies have shown that psychological contract violation could be associated with organizational cynicism (e.g., Andersson, 1996; Dean et al., 1998; Chrobot-Mason, 2003; Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly, 2003). As we know, psychological contract violation involves employees’ perception that their employing organization fails to fulfill promised obligations or duties (Morrison and Robinson, 1997). Furthermore, this negative perception (i.e., psychological contract violation) could make employees feel distrust towards their organization, and then the cynical attitude towards organization may be strengthened (Robinson et al., 1994). On the basis of these studies, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

simple H4:

Psychological contract violation is positively related to organizational cynicism.

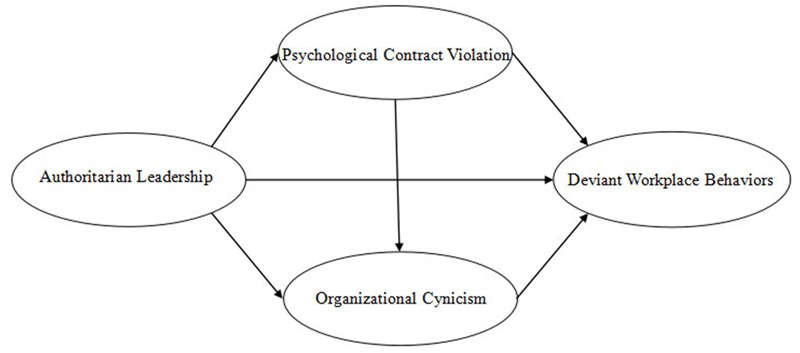

To sum up, a set of hypotheses have been derived from existing theory and prior research. Then several multivariate models will be constructed to test these hypotheses, specifically the proposed mediating roles of psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism between authoritarian leadership and DWB. Based on these analyses mentioned above, the present study puts forward the following hypothetical model shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Hypothetical model.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedures

The sample consisted of 391 workers from five manufacturing enterprises in a northern city of China. We collected data from full-time employees who had worked together and frequently interacted with their supervisors. At first, a total of 470 questionnaires were distributed, and 453 questionnaires were returned for an overall return rate of 96.4%. Two surveys were not included due to incomplete or illegible responses. Additionally, the participants who indicated that they did not have a supervisor had been excluded, because they were unable to provide meaningful ratings on the focal variable, perceived authoritarian leadership. Finally, 391 (83.2%) valid questionnaire were received.

The jobs held by these employees varied widely, including repairman, quality inspectors, operator, material manager, and other manufacture related activities. The respondents were mainly men (n = 271, 69.3%), and they are mostly between the ages of 26 and 45, which make up 60.4% of the total. The majority of the participants were junior college (vocational education, 36.5%) and undergraduate college (undergraduate education, 42.0%). Moreover, 60.2% of the respondents possessed 3–5 years’ work experience. In addition, 10.6% of the participants had a low- or mid-level leadership position (7.4% first-line manager, 3.2% department middle management staff).

From January to February 2015, we contacted with several manufacturing enterprises and asked them to participate in this investigation. After getting approval, the managers of each enterprise introduced the human resource department staffs to us. We told them the purpose of this survey, proper ways of collecting data in addition to the detailed precautions in the survey. At the beginning of the investigation, we introduced the voluntary nature of this survey and assured anonymity and confidentiality to the participants. To express our appreciation, participants were given a $5 gift certificate to a local store as long as they completed the questionnaire. This study was part of a larger research project on leadership behaviors, for which the first author had received ethical clearance from the university ethical review process.

Measures

A 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), was used to measure the participants’ responses for each item. The scales used to measure each variable were adapted from relevant prior research. All scales items were translated into Chinese by professional translators following a double blind back-translation procedure (Schaffer and Riordan, 2003) to ensure semantic equivalence with the original English wording. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each scale.

Authoritarian Leadership

Authoritarian leadership was measured by the 9-item version of the Authoritarian Leadership Questionnaire by Farh and Cheng (2000). Sample items were “My supervisor asks me to obey his/her instructions completely”, “My supervisor always has the last say in the meeting”, and “My supervisor scolds us when we cannot accomplish our task”. Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.87.

Psychological Contract Violation

Psychological contract violation was measured by the Psychological Contract Violation Questionnaire (Robinson and Morrison, 2000). Sample items include “I feel betrayed by my organization”, “I feel that my organization has violated the contract between us”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90 for this scale.

Organizational Cynicism

We used the Organizational Cynicism Questionnaire developed by Dean et al. (1998) to measure organizational cynicism. Examples of statements are “Company policies, goals and practices are often inconsistent”, “I feel angry when I think of the company”, “I often laugh at the company’s slogan and actions”. The scale consisted of three dimensions: cynicism faith (α = 0.92), cynicism emotion (α = 0.93) and cynicism behaviors (α = 0.84). Cronbach’s alpha of the total scale was 0.94.

Deviant Workplace Behaviors

Deviant Workplace Behaviors Questionnaire (Bennett and Robinson, 2000) was adopted to measure DWB. It was a multidimensional construct including two portions: (a) 7 items for interpersonal deviance (α = 0.91), (b) 12 items for organizational deviance (α = 0.93). The example items were “Acted rudely toward someone at work”, “Dragged out work in order to get overtime”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95 for the total scale.

Results

Description

Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, and correlations for each of the constructs. It was found that authoritarian leadership was significantly and positively correlated with employees’ DWB (r = 0.23, p < 0.01), psychological contract violation (r = 0.33, p < 0.01) and organizational cynicism (r = 0.38, p < 0.01). These results provided initial support for H1, H2a, and H3a, respectively. Psychological contract violation was significantly and positively correlated with DWB (r = 0.60, p < 0.01) which provided initial support for H2b. Organizational cynicism was significantly and positively correlated with DWB (r = 0.37, p < 0.01) and psychological contract violation (r = 0.59, p < 0.01) which provided initial support for H3b and H4.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among all variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Authoritarian leadership | (0.87) | |||

| (2) Organizational cynicism | 0.38∗∗ | (0.94) | ||

| (3) Psychological contract violation | 0.33∗∗ | 0.59∗∗ | (0.90) | |

| (4) Deviant workplace behaviors | 0.23∗∗ | 0.37∗∗ | 0.60∗∗ | (0.95) |

| Mean | 3.36 | 2.10 | 2.03 | 3.03 |

| SD | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.37 |

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are in parentheses on the diagonal.

∗∗p < 0.01.

Measurement Model Testing

The measurement model consisted of four latent factors (authoritarian leadership, psychological contract violation, organizational cynicism and DWB) and eleven observed indicators. The observed indicators were formed by the method of item parceling (i.e., aggregating individual items into several parcels). Compared with item-level data, aggregate-level data has several advantages, such as higher communality, higher ratio of common-to-unique factor variance, and lower random error (Matsunaga, 2008). The goodness of fit of the model was evaluated using the following indices (Kline, 2005): (a) chi-square statistics; (b) root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA): best if below.08; (c) goodness-of-fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), comparative fit index (CFI): best if above 0.90.

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood estimation using AMOS 21.0 to examine whether employees’ scores on their self-report measures (i.e., authoritarian leadership, psychological contract violation, organizational cynicism and DWB) captured distinctive constructs. We compared the fitness between a one-factor model (all observed indicators loaded on one factor), two-factor model (authoritarian leadership and psychological contract violation on one factor, organizational cynicism and DWB on the other), three-factor model (authoritarian leadership and psychological contract violation on one factor, organizational cynicism and DWB as separate factors) and four-factor model (authoritarian leadership, psychological contract violation, organizational cynicism and DWB as separate factors). The results (see Table 2) indicated that the four-factor model fitted the data better than other models.

Table 2.

Fit indices for measurement models.

| Structure | χ2 | df | GFI | NFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-factor | 355.52 | 44 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.085 |

| 2-factor | 333.25 | 43 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.077 |

| 3-factor | 291.11 | 41 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.074 |

| 4-factor | 144.02 | 38 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.069 |

| 5-factor | 130.95 | 27 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.065 |

N = 391. 1-factor: AL + PCV + OC + DWB; 2-factor: AL + PCV, OC + DWB; 3-factor: AL + PCV, OC, DWB; 4-factor: AL, PCV, OC, DWB; 5-factor: AL, PCV, OC, DWB, CMV. AL, authoritarian leadership; OC, organizational cynicism; PCV, psychological contract violation; DWB, deviant workplace behaviors; CMV, common method variance.

In order to determine whether common method variance was problematic, we employed Harman’s single-factor test (Harman, 1976) to test whether the majority of the variance could be accounted for by one general factor. The results showed that the first factor accounted for only 29.46% of the variance, less than half, and this finding could be accepted (Harris et al., 2013). Furthermore, common method variance was tested by using the CFA marker technique (Podsakoff et al., 2012). We performed a CFA (5-factor model) in which a common method factor was added to 4-factor model. The results indicated the inclusion of the common method variance in 5-factor model did not improve the overall model fit of 4-factor model significantly (Table 2). Thus, it was determined that the common method bias was not a problem in this study.

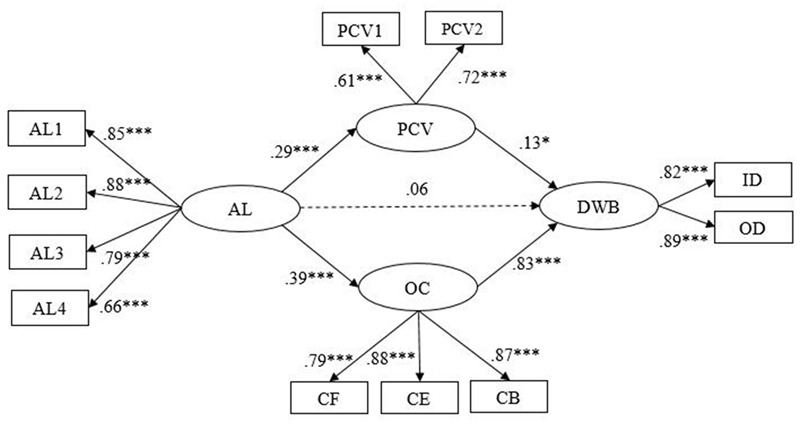

Structure Model Testing

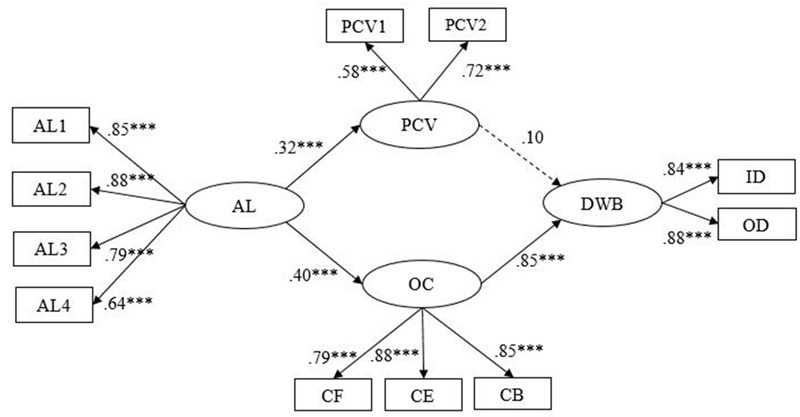

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test our Hypotheses 1–4 and to assess the appropriateness and fit of our proposed theoretical model. First, we built a partial-mediated model (Model 1). The results showed that Model 1 did not fit the data well (see Table 3), and the path from authoritarian leadership to employees’ DWB was not significant (β = 0.06, p > 0.05) (see Figure 2). Then we deleted the non-significant path based on the Model 1 and built the fully mediated model (Model 2) (see Figure 3). The results indicated that Model 2 fitted well to the data (see Table 3), but the path from psychological contract violation to employees’ DWB was non-significant (β = 0.10, p > 0.05). The chi-square difference between Model 1 and Model 2 reached the significant level (Δχ2 (1) = 60.80, p < 0.001), which suggested that Model 2 fitted better than Model 1 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of the structural models.

| Model | χ2 | df | GFI | NFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (Partially mediated model) | 242.52 | 39 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.095 |

| M2 (Fully mediated model) | 181.72 | 40 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.068 |

| M3 (The final model) | 135.88 | 39 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.057 |

GFI, goodness-of-fit index; NFI, normed fit index; CFI, comparative fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

FIGURE 2.

Partial-mediated model (Model 1). AL1–AL4 are four parcels of authoritarian leadership (AL1–AL3 aggregates of two items and AL4 was three items from the Authoritarian Leadership Questionnaire); PCV, psychological contract violation; OC, organizational cynicism; DWB, deviant workplace behaviors; PCV1 aggregates of two items and PCV2 was two items from Psychological Contract Violation Questionnaire; CF, cynicism faith; CB, cynicism behavior; CE, cynicism emotion; CF, CB, and CE are three dimensions of the Organizational Cynicism Questionnaire; ID, interpersonal deviation; OD, organizational deviation; ID and OD are two dimensions of the Deviant Workplace Behaviors Questionnaire. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

FIGURE 3.

Fully mediated model (Model 2). AL1–AL4 are four parcels of authoritarian leadership (AL1–AL3 aggregates of two items and AL4 was three items from the Authoritarian Leadership Questionnaire); PCV, psychological contract violation; OC, organizational cynicism; DWB, deviant workplace behaviors; PCV1 aggregates of two items and PCV2 was two items from Psychological Contract Violation Questionnaire; CF, cynicism faith; CB, cynicism behavior; CE, cynicism emotion; CF, CB, and CE are three dimensions of the Organizational Cynicism Questionnaire; ID, interpersonal deviation; OD, organizational deviation; ED and OD are two dimensions of the Deviant Workplace Behaviors Questionnaire. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

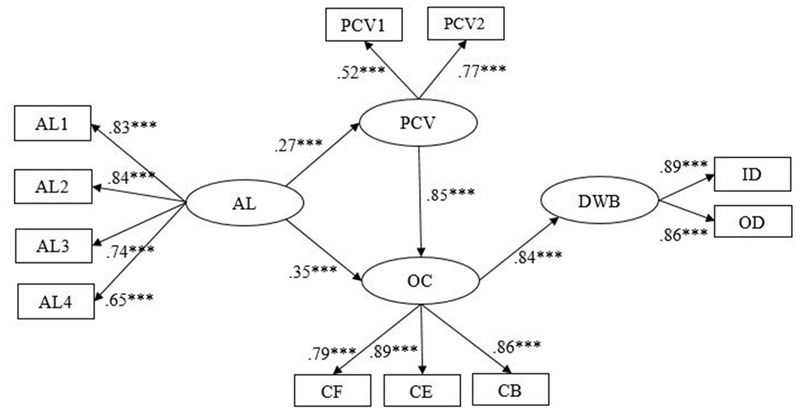

Second, in order to determine the best model, we developed another alternative model (Model 3). For Model 3, we deleted the non-significant path and added a path between psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism based on the Model 2 (see Figure 4). The chi-square difference between Model 2 and Model 3 reached the significant level (Δχ2 (1) = 45.84, p < 0.001). The results indicated that compared with Model 2, Model 3 provided a better fit to the data (see Table 3). Therefore, Model 3 was chosen as our final structural model.

FIGURE 4.

The final mediation model (Model 3). AL1–AL4 are four parcels of authoritarian leadership (AL1–AL3 aggregates of two items and AL4 was three items from the Authoritarian Leadership Questionnaire); PCV, psychological contract violation; OC, organizational cynicism; DWB, deviant workplace behaviors; PCV1 aggregates of two items and PCV2 was two items from Psychological Contract Violation Questionnaire; CF, cynicism faith; CB, cynicism behavior; CE, cynicism emotion; CF, CB, and CE are three dimensions of the Organizational Cynicism Questionnaire; ID, interpersonal deviation; OD, organizational deviation; ID and OD are two dimensions of the Deviant Workplace Behaviors Questionnaire. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Further, we tested the mediation effects identified in Model 3 using the bootstrapping method (Preacher and Hayes, 2008; Hayes, 2013). The SEM results supported our hypotheses. First, as depicted in Table 4 and Figure 4, psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism mediated the relationship between authoritarian leadership and DWB, and the significant mediation effects comprised: (a) the indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on DWB via organizational cynicism, (b) the indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on DWB via psychological contract violation followed by organizational cynicism. Therefore, H1, H2c, and H3c were supported. Second, the path coefficient from authoritarian leadership to psychological contract violation was positively significant (β = 0.27, p < 0.001), supporting H2a. Third, the path coefficient between authoritarian leadership and organizational cynicism was significant (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), so H3a was supported. Fourth, the path coefficient from organizational cynicism to DWB was significant (β = 0.84, p < 0.001), supporting H3b. Fifth, H4 was supported by the results: the path coefficient between psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism was significant (β = 0.85, p < 0.001). Sixth, the indirect effect of organizational cynicism in the link between psychological contract violation and DWB (PCV→OC→DWB) was significant (β = 0.71, p < 0.001) (see Table 4). This result demonstrated that psychological contract violation was positively related to DWB, through the indirect effect of organizational cynicism. Therefore, H2b was supported.

Table 4.

Direct and indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals in final model 3.

| Model pathways | Estimated effect | 95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bounds | Upper bounds | ||

| Total effect | |||

| AL→ DWB | 0.48∗∗∗ | 0.36 | 0.59 |

| Direct effects | |||

| AL→PCV | 0.27∗∗∗ | 0.18 | 0.36 |

| AL→ OC | 0.35∗∗∗ | 0.27 | 0.42 |

| PCV→ OC | 0.85∗∗∗ | 0.78 | 0.92 |

| OC→ DWB | 0.84∗∗∗ | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| Indirect effects | |||

| AL→OC→DWB | 0.29∗∗ | 0.18 | 0.42 |

| PCV→ OC→ DWB | 0.71∗∗∗ | 0.62 | 0.80 |

| AL→ PCV→ OC→ DWB | 0.19∗ | 0.08 | 0.31 |

AL, authoritarian leadership; OC, organizational cynicism; PCV, psychological contract violation; DWB, deviant workplace behaviors.

∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Discussion

Our results show that the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employees’ DWB is fully mediated by psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism, which indicates that Model 2 (fully mediated model) fits better than Model 1 (partially mediated model). This result suggests that employees under authoritarian leadership tend to perceive higher psychological contract violation and higher organization cynicism, both of which are positively related to their DWB. Moreover, we find the link between authoritarian leadership and DWB is sequentially mediated by psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism, which supports that Model 3 fits better than Model 2. It is indicated that when leader adopts an authoritarian approach, their followers are more likely to experience psychological contract violation. Then, this sense of psychological contract violation is positively related to followers’ perception of organizational cynicism, which can be associated with their DWB.

Theoretical Implications

First, based on the Social Exchange Theory, our findings provide an alternative lens through which to understand the underlying mechanism of the authoritarian leadership-DWB relationship. Drawing from Social Exchange Theory (Gouldner, 1960; Blau, 1964), employees can react to the social exchange relationship, which is initiated and shaped by the leaders’ actions. In this light, this study demonstrates that authoritarian leadership has a positive relationship with employees’ DWB, which is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Farh and Cheng, 2000; Schuh et al., 2013). More importantly, psychological contract violation (Brown and Moshavi, 2002) and organizational cynicism (Neves, 2012), both of which could reflect the quality of social relation between leaders and followers, are found to mediate the link between authoritarian leadership and DWB. These results contribute to current research by suggesting that the propositions from Social Exchange Theory can be extended to explain the underlying mechanism behind the relationship between authoritarian leadership and followers’ behaviors.

Moreover, our work adds to the body of literature on authoritarian leadership. Overall, this study offers an important contribution to the authoritarian leadership literature by demonstrating its relationship with employees’ negative perception and behaviors towards the organization. Prior research has emphasized that authoritarian leadership has a negative relationship with subordinates’ positive attitudes and behaviors, such as organizational commitment (Erben and Güneşer, 2008) and organizational citizenship behavior (Salam et al., 1996). However, little attention has been paid to the link between authoritarian leadership and employee’s negative attitudes and behaviors, which are frequently observed in the workplace. Thus, this study enriches the existing research by demonstrating the relationship between authoritarian leadership and negative aspects (i.e., psychological contract violation, organizational cynicism and DWB).

Last but not the least, our research has advanced the understanding of the mediating roles of psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to propose the mediating roles of both psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism within the same structural model. Previous research has only investigated the mediating role of psychological contract violation (e.g., Ahmed and Muchiri, 2014; Liao et al., in press) or organizational cynicism (e.g., Gkorezis et al., 2015) in the link between leadership and work-related aspects. In contrast to prior work, by taking both psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism into consideration, the current research has unveiled the underlying mechanism that explains the authoritarian leadership-DWB link.

Practical Implications

Our findings hold several important managerial implications. First and foremost, our results demonstrate that authoritarian leadership is associated with a number of negative work-related aspects. In this light, the occurrence of authoritarian leadership should be reduced by carefully selecting and training supervisors. For example, the personality characteristic of “dominance” (i.e., the levels of assertiveness, aggression, and cooperation) assessed by 16PF Questionnaire (Cattell et al., 1970) should be considered as one of indices in the supervisor recruitment system. Moreover, organizations might provide supervisors with training courses to improve their interpersonal relationship skills (Aryee et al., 2007). Additionally, leaders themselves should try to create an equity and harmonious working environment, and show benevolence to employees. However, it is noteworthy that the relationship between authoritarian leadership and poor performance of subordinates might not always be stable (Farh et al., 2008). Under some circumstances, such as tight deadlines and crisis situations, authoritarian leadership may be needed to obtain desirable outcomes. For example, authoritarian leadership could be effective in promoting subordinates’ effort in urgent situation (Niu et al., 2009), and giving them motivation to achieve goals (Chan et al., 2013). Thus, it is suggested that leaders should apply different leadership style under different situations (Yang et al., 2012). In other words, the overuse of any one leadership style may disappoint employees or harm leadership effectiveness.

Moreover, in line with previous studies, our results have demonstrated that psychological contract violation is positively related to negative attitude of cynicism (e.g., Chrobot-Mason, 2003; Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly, 2003), and employees’ DWB (e.g., Restubog et al., 2007; Bordia et al., 2008). Thus, leaders should adopt some management strategies to fulfill followers’ psychological contract. For example, leaders can ask for subordinates’ opinions to elevate their sense of participation, share management power to inspire employees’ loyalty to the organization, and show concern for subordinates’ well-being in both work and family domains.

Finally, in order to reduce organizational cynicism in the workplace, organization should use different approaches to increase trustworthiness, such as offering organizational support, treating all the employees fairly. In addition, organizations should provide a communication platform where employees could share work-related information, keep track of the company policies, and complain online with supervisors, so that a better exchange relationship would be built based on trust.

Limitations and Future Research

The results of this research should be interpreted with respect to a number of limitations that may shed light on future research directions. First, this research is cross-sectional in nature, and no causal relationship between variables of interest in our study could be established. The longitudinal effects of organizational or psychological factors on employees’ DWB remain unexplored. It is possible that a one-occasion test of a mediation model is not adequate, particularly as a temporal sequence is proposed in our study. Thus, addressing the causality issue using a longitudinal design to test the current study model would nevertheless be a fruitful avenue for future research.

Second, although our research has demonstrated that authoritarian leadership can be positively linked with employees’ DWB. However, it is also found that if leaders perceive that the goals of organization or their own interests are defeated by followers’ behaviors, they would implement a destructive leadership style (Krasikova et al., 2013). It is suggested that followers’ DWB might be predictive of leaders’ behaviors, such as authoritarian leadership. As mentioned before, leaders may vary behaviors according to different circumstances (Yang et al., 2012). Therefore, it is recommended that future research should examine the role of followers in shaping leaders’ behaviors.

Third, this study only focuses on psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism as mediating variables. Testing other mediators such as perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange, may provide further insights regarding the mechanism underlying the link between authoritarian leadership and employees’ DWB.

Despite these limitations, this study makes several important contributions. To our knowledge, the current research represents the first attempt to investigate both psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism in one study to examine the underlying mechanism behind the link between authoritarian leadership and employees’ DWB. The results suggest that the relationship between authoritarian leadership and DWB is mediated by organizational cynicism. Moreover, this relationship is also sequentially mediated by psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism. In consideration of the probable mechanism, these findings could provide valuable guidance for how to reduce employees’ DWB.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of ethics committee of China University of Mining and Technology with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of China University of Mining and Technology.

Author Contributions

HJ: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, drafting and revising the paper, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. YC: substantial contributions to drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content. PS: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, and the communication with the journal during the manuscript submission, peer review, and publication process. JY: substantial contributions to data acquisition and data analysis.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71672187, 71302141), China Postdoctoral Science Special Foundation (2016T90529, 2013M541761), National Social Science Foundation of China (15CSH052), Qing Lan Project of Jiangsu Province (2017).

References

- Agnew R. (1992). Foundation for a general theory of crime. Criminology 30 47–87. 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01093.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R. (2006). “General strain theory: current status and directions for further research,” in Taking Stock: The Status of Criminological Theory eds Cullen F. T., Wright J. P., Blevins K. R. (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; ) 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed E., Muchiri M. (2014). Effects of psychological contract breach, ethical leadership and supervisors’ fairness on employees’ performance and well-being. World 5 1–13. 10.21102/wjm.2014.09.52.01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alias M., Mohd Rasdi R., Ismail M., Abu Samah B. (2013). Predictors of workplace deviant behaviour: HRD agenda for Malaysian support personnel. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 37 161–182. 10.1108/03090591311301671 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson L. M. (1996). Employee cynicism: an examination using a contract violation framework. Hum. Relations 49 1395–1418. 10.1177/001872679604901102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino K., Lewis M. U., Bradfield M. (1999). Justice constructs, negative affectivity, and employee deviance: a proposed model and empirical test. J. Organ. Behav. 20 1073–1091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aryee S., Chen Z. X., Sun L. Y., Debrah Y. A. (2007). Antecedents and outcomes of abusive supervision: test of a trickle-down model. J. Appl. Psychol. 92 191–201. 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass B. M. (1990). Bass & Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications. New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R. J., Robinson S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 85 349–360. 10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blau P. M. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bordia P., Restubog S. L., Tang R. L. (2008). When employees strike back: investigating mediating mechanisms between psychological contract breach and workplace deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 93 1104–1117. 10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown F. W., Moshavi D. (2002). Herding academic cats: faculty reactions to transformational and contingent reward leadership by department chairs. J. Leadersh. Stud. 8 79–93. 10.1177/107179190200800307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cattell R. B., Eber H. W., Tatsuoka M. M. (1970). Handbook for the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire. Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing. [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. C., Huang X., Snape E., Lam C. K. (2013). The Janus face of paternalistic leaders: authoritarianism, benevolence, subordinates’ organization-based self-esteem, and performance. J. Organ. Behav. 34 108–128. 10.1002/job.1797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chemers M. (1997). An Integrative Theory of Leadership. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. C., Chen Y. R., Xin K. (2004). Guanxi practices and trust in management: a procedural justice perspective. Organ. Sci. 15 200–209. 10.1287/orsc.1030.0047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. P., Eberly M. B., Chiang T. J., Farh J. L., Cheng B. S. (2014). Affective trust in Chinese leaders: linking paternalistic leadership to employee performance. J. Manage. 40 796–819. 10.1177/0149206311410604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng B. S., Chou L. F., Wu T. Y., Huang M. P., Farh J. L. (2004). Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 7 89–117. 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2004.00137.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chrobot-Mason D. L. (2003). Keeping the promise: psychological contract violations for minority employees. J. Manag. Psychol. 18 22–45. 10.1108/02683940310459574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger J. A., Kanungo R. N. (1998). Charismatic Leadership in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dean J. W., Jr., Brandes P., Dharwadkar R. (1998). Organizational cynicism. Acad. Manage. Rev. 23 341–352. 10.2307/259378 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erben G. S., Güneşer A. B. (2008). The relationship between paternalistic leadership and organizational commitment: investigating the role of climate regarding ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 82 955–968. 10.1007/s10551-007-9605-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans W. R., Goodman J. M., Davis W. D. (2010). The impact of perceived corporate citizenship on organizational cynicism. OCB, and employee deviance. Hum. Perform. 24 79–97. 10.1080/08959285.2010.530632 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farh J. L., Cheng B. S. (2000). “A cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations,” in Management and Organizations in Chinese Context eds Li J. T., Tsui A. S., Walton S. E. (London: MacMillan; ) 95–197. [Google Scholar]

- Farh J. L., Cheng B. S., Chou L. F., Chu X. P. (2006). “Authority and benevolence: employees’ responses to paternalistic leadership in China,” in China’s Domestic Private Firms: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Management and Performance eds Tsui A. S., Bian Y., Cheng L. (New York, NY: Sharpe; ) 230–260. [Google Scholar]

- Farh J. L., Liang J., Chou L. F., Cheng B. S. (2008). “Paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations: research progress and future research directions,” in Business Leadership in China: Philosophies, Theories, and Practices eds Chen C. C., Lee Y. T. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ) 171–205. [Google Scholar]

- Flood P. C., Hannan E., Smith K. G., Turner T., West M. A., Dawson J. (2000). Chief executive leadership style, consensus decision making, and top management team effectiveness. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 9 401–420. 10.1080/135943200417984 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gkorezis P., Petridou E., Krouklidou T. (2015). The detrimental effect of machiavellian leadership on employees’ emotional exhaustion: organizational cynicism as a mediator. Eur. J. Psychol. 11 619–631. 10.5964/ejop.v11i4.988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner H. P. (1960). Dimensions of organizational commitment. Adm. Sci. Q. 4 468–490. 10.2307/2390769 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J., Alge B. (1998). “Aggressive reactions to workplace injustice,” in Dysfunctional Behavior in Organizations eds Griffin R. W., O’Leary-Kelly A. (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; ) 119–145. [Google Scholar]

- Harman H. H. (1976). Modern Factor Analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris K. J., Marett K., Harris R. B. (2013). An investigation of the impact of abusive supervision on technology end-users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 29 2480–2489. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- James S. M. (2005). Antecedents and Consequences of Cynicism in Organizations: An Examination of Potential Positive and Negative Effects on School Systems. Doctoral dissertation, Florida State University; Tallahassee, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. L., O’Leary-Kelly A. M. (2003). The effects of psychological contract breach and organizational cynicism: not all social exchange violations are created equal. J. Organ. Behav. 24 627–647. 10.1002/job.207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter D. L., Mirvis P. H. (1989). The Cynical Americans: Living and Working in an Age of Discontent and Disillusion. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Kiazad K., Restubog S. L. D., Zagenczyk T. J., Kiewitz C., Tang R. L. (2010). In pursuit of power: the role of authoritarian leadership in the relationship between supervisors’ machiavellianism and subordinates’ perceptions of abusive supervisory behavior. J. Res. Pers. 44 512–519. 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. B. (2005). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter J. P. (1973). The psychological contract: managing the joining-up process. Calif. Manage. Rev. 15 91–99. 10.2307/41164442 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krasikova D. V., Green S. G., LeBreton J. M. (2013). Destructive leadership a theoretical review, integration, and future research agenda. J. Manage. 39 1308–1338. 10.1177/0149206312471388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter M. P., Harvie P. (1997). Correspondence of supervisor and subordinate perspectives during major organizational change. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2 343–352. 10.1037/1076-8998.2.4.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson H. (1965). Reciprocation: the relationship between man and organization. Adm. Sci. Q. 9 370–390. 10.2307/2391032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson H., Molinari J., Spohn A. G. (1972). Organizational Diagnosis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liao S. H., Widowati R., Hu D. C., Tasman L. The mediating effect of psychological contract in the relationships between paternalistic leadership and turnover intention for foreign workers in Taiwan. Asia Pac. Manage. Rev. doi: 10.1016/j.apmrv.2016.08.003. (in press) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorinkova N. M., Perry S. J. (2014). When is empowerment effective? The role of leader-leader exchange in empowering leadership, cynicism, and time theft. J. Manage. 43 1631–1654. 10.1177/0149206314560411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga M. (2008). Item parceling in structural equation modeling: a primer. Commun. Methods Meas. 2 260–293. 10.1080/19312450802458935 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison E. W., Robinson S. L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: a model of how psychological contract violation develops. Acad. Manage. Rev. 22 226–256. 10.2307/259230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mount M., Ilies R., Johnson E. (2006). Relationship of personality traits and counterproductive work behaviors: the mediating effects of job satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 59 591–622. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00048.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neves P. (2012). Organizational cynicism: spillover effects on supervisor-subordinate relationships and performance. Leadersh. Q. 23 965–976. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.06.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neves P., Caetano A. (2006). Social exchange processes in organizational change: the roles of trust and control. J. Change Manage. 6 351–364. 10.1080/14697010601054008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niu C. P., Wang A. C., Cheng B. S. (2009). Effectiveness of a moral and benevolent leader: probing the interactions of the dimensions of paternalistic leadership. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 12 32–39. 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2008.01267.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill T. A., Hastings S. E. (2011). Explaining workplace deviance behavior with more than just the “Big Five”. Pers. Individ. Dif. 50 268–273. 10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortony A., Clore G. L., Collins A. (1988). The Cognitive Structure of Emotions. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511571299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P. M., MacKenzie S. B., Podsakoff N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63 539–569. 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., Hayes A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40 879–891. 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restubog S. L. D., Bordia P., Tang R. L. (2007). Behavioral outcomes of psychological contract breach in a non-western culture: the moderating role of equity sensitivity. Br. J. Manage. 18 376–386. 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00531.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S. L., Bennett R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: a multidimensional scaling study. Acad. Manage. J. 38 555–572. 10.2307/256693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S. L., Kraatz M. S., Rousseau D. M. (1994). Changing obligations and the psychological contract: a longitudinal study. Acad. Manage. J. 37 137–152. 10.2307/256773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S. L., Morrison E. W. (2000). The development of psychological contract breach and violation: a longitudinal study. J. Organ. Behav. 21 525–546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Responsibil. Rights J. 2 121–139. 10.1007/BF01384942 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salam S., Cox J., Sims H. P. (1996). How to make a team work: mediating effects of job satisfaction between leadership and team citizenship. Acad. Manage. Proc. 1996 293–297. 10.5465/AMBPP.1996.4980731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer B. S., Riordan C. M. (2003). A review of cross-cultural methodologies for organizational research: a best-practices approach. Organ. Res. Methods 6 169–215. 10.1177/1094428103251542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuh S. C., Zhang X. A., Tian P. (2013). For the good or the bad? Interactive effects of transformational leadership with moral and authoritarian leadership behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 116 629–640. 10.1007/s10551-012-1486-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M. E. (1955). A comparison of two types of leadership in various communication nets. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 50 127–134. 10.1037/h0041129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman T. D. (2005). Biting the Hand that Feeds: The Employee Theft Epidemic. West Conshohocken, PA: Infinity Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Spector P. E. (1997). “The role of frustration in antisocial behavior at work,” in Antisocial Behavior in Organizations eds Giacalone R. A., Greenberg J. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; ) 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. (2007). Re: Gambling at Work “Costs Employers£ 300M a Year”. Available at: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/55009c0e-a43d-11db-bec4-0000779e2340.html#axzz2mZJbxzmB [accessed January 4, 2007]. [Google Scholar]

- Tepper B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Acad. Manage. J. 43 178–190. 10.2307/1556375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treadway D. C., Hochwarter W. A., Ferris G. R., Kacmar C. J., Douglas C., Ammeter A. P., et al. (2004). Leader political skill and employee reaction. Leadersh. Q. 15 493–513. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui A. S., Wang H., Xin K., Zhang L., Fu P. P. (2004). “Let a thousand flowers bloom”: variation of leadership styles among Chinese CEOs. Organ. Dyn. 33 5–20. 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2003.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turnley W. H., Bolino M. C., Lester S. W., Bloodgood J. M. (2003). The impact of psychological contract fulfillment on the performance of in-role and organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Manage. 29 187–206. 10.1016/S0149-2063(02)00214-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa F. O., Avolio B. J., Gardner W. L., Wernsing T. S., Peterson S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: development and validation of a theory-based measure. J. Manage. 34 89–126. 10.1177/0149206307308913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A. C., Chiang T. J., Tsai C. Y., Lin T. T., Cheng B. S. (2013). Gender makes the difference: the moderating role of leader gender on the relationship between leadership styles and subordinate performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 122 101–113. 10.1016/j.obhdp.2013.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M., Huang X., Li C., Liu W. (2012). Perceived interactional justice and trust-in-supervisor as mediators for paternalistic leadership. Manage. Organ. Rev. 8 97–121. 10.1111/j.1740-8784.2011.00283.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. R., Wu K. S., Wang F. K., Chin P. C. (2012). Relationships among project manager’s leadership style, team interaction and project performance in the Taiwanese server industry. Qual. Quant. 46 207–219. 10.1007/s11135-010-9354-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Luo X. R., Liao Q., Peng L. (2015). Does IT team climate matter? An empirical study of the impact of co-workers and the Confucian work ethic on deviance behavior. Inform. Manage. 52 658–667. 10.1016/j.im.2015.05.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]