Abstract

Rationale: Maintenance of a surface immune barrier is important for homeostasis in organs with mucosal surfaces that interface with the external environment; however, the role of the mucosal immune system in chronic lung diseases is incompletely understood.

Objectives: We examined the relationship between secretory IgA (SIgA) on the mucosal surface of small airways and parameters of inflammation and airway wall remodeling in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Methods: We studied 1,104 small airways (<2 mm in diameter) from 50 former smokers with COPD and 39 control subjects. Small airways were identified on serial tissue sections and examined for epithelial morphology, SIgA, bacterial DNA, nuclear factor-κB activation, neutrophil and macrophage infiltration, and airway wall thickness.

Measurements and Main Results: Morphometric evaluation of small airways revealed increased mean airway wall thickness and inflammatory cell counts in lungs from patients with COPD compared with control subjects, whereas SIgA level on the mucosal surface was decreased. However, when small airways were classified as SIgA intact or SIgA deficient, we found that pathologic changes were localized almost exclusively to SIgA-deficient airways, regardless of study group. SIgA-deficient airways were characterized by (1) abnormal epithelial morphology, (2) invasion of bacteria across the apical epithelial barrier, (3) nuclear factor-κB activation, (4) accumulation of macrophages and neutrophils, and (5) fibrotic remodeling of the airway wall.

Conclusions: Our findings support the concept that localized, acquired SIgA deficiency in individual small airways of patients with COPD allows colonizing bacteria to cross the epithelial barrier and drive persistent inflammation and airway wall remodeling, even after smoking cessation.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, small airways, secretory IgA, neutrophils, NF-κB

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Pathologic changes in small (<2 mm) airways contribute to progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; however, the mechanisms driving ongoing fibrotic remodeling and persistent inflammation in these airways are not well understood.

What This Study Adds to the Field

In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inflammation and fibrotic remodeling are localized to individual small airways with reduced secretory IgA (SIgA) on the mucosal surface. These SIgA-deficient small airways are also characterized by structurally abnormal epithelium, frequent bacterial invasion across the mucosal surface, epithelial nuclear factor-κB activation, and accumulation of inflammatory cells. Together, our studies support the concept that an acquired defect in mucosal immunity underlies persistent inflammation and remodeling of small airways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by persistent inflammation and fixed airflow obstruction (1–3). In COPD, small airway resistance is increased fourfold to 40-fold compared with control subjects (4, 5), indicating that changes within small conducting airways are central components of disease pathology. Luminal mucus plugging, airway inflammation, and fibrotic remodeling all seem to contribute to small airway obstruction (6–8). However, current concepts of disease pathogenesis fail to fully explain the role of small airways in initiation and progression of COPD, particularly the persistence of airway inflammation and airway wall remodeling after smoking cessation.

In addition to facilitating mucociliary clearance and responding to inhaled antigens and inflammatory stimuli (9, 10), airway epithelium facilitates host defense by transporting IgA from the basolateral compartment to the airway surface (11, 12). In small airways, IgA is produced locally by subepithelial plasma cells as polymeric IgA, which is then transported across airway epithelial cells via the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR). After transport to the mucosal surface, pIgR is cleaved and a portion of pIgR (designated as secretory component) remains attached to form secretory IgA (SIgA). In 2001, Pilette and coworkers (13) reported that secretory component expression is reduced in airways of patients with COPD. Subsequently, we showed that pIgR expression is down-regulated in COPD and that airway surface SIgA deficiency is widespread in COPD and correlates with severity of airflow obstruction (14, 15). Consistent with these observations, cultured airway epithelial cells from patients with COPD were reported to express lower levels of pIgR than airway epithelial cells from healthy control subjects (16). The importance of SIgA in COPD is further supported by our recent demonstration that pIgR-deficient mice, which cannot transcytose IgA to mucosal surfaces, develop a spontaneous COPD-like phenotype, including emphysema and fibrotic remodeling of small airways (17).

To further investigate the impact of localized SIgA deficiency in small airways on the pathobiology of COPD, we studied individual airways in lung tissue samples obtained from patients with COPD and control subjects. We found that reduction of SIgA on the surface of individual small airways correlates with parameters of inflammation and bacterial invasion of the epithelial barrier, and fibrotic thickening of airway walls. Together with other published data, these results suggest that defects in mucosal immunity contribute to chronic airway inflammation and progression of COPD.

Methods

Patients and Lung Parenchymal Tissue Specimens

Lung tissue specimens containing small airways (diameter <2 mm) were collected from lifelong nonsmokers without lung disease and former smokers with or without COPD (Table 1). The severity of COPD was determined using Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria (2, 3). Tissue specimens from 24 lifelong nonsmokers and 11 former smokers without COPD were obtained from donor lungs that were not used for lung transplantation. Tissue specimens from four former smokers without COPD and 20 patients with mild to moderate COPD (GOLD stage I–II) were obtained from lungs resected for solitary tumors, whereas tissue specimens from 30 patients with severe to very severe COPD (GOLD stage III–IV) were obtained from the explanted lungs of transplant recipients. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Vanderbilt University and University of California at San Francisco.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

| Lifelong Nonsmokers without COPD | Former Smokers without COPD | Patients with COPD Ranged by GOLD Criteria (2, 3) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPD I | COPD II | COPD III | COPD IV | |||

| Number of study participants | ||||||

| VUMC | 1 | 4 | 7 | 13 | 9 | 21 |

| UCSF | 23 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FEV1, % of predicted* | N/A | 109 (99–121) | 84 (81–95) | 65 (53–74) | 34 (30–48) | 21 (12–29) |

| FEV1/FVC* | N/A | 0.79 (0.75–0.80) | 0.66 (0.58–0.68) | 0.56 (0.40–0.66) | 0.38 (0.32–0.53) | 0.31 (0.21–0.57) |

| Age, yr† | 52.0 ± 15.5 | 57.7 ± 12.2 | 64.7 ± 5.6‡ | 69.3 ± 8.0‡ | 62.2 ± 7.9 | 55.2 ± 5.9 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 7 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 10 |

| Female | 17 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 11 |

| Smoking history† | ||||||

| Pack-years | N/A | 37.2 ± 13.1 | 49.9 ± 14.1 | 60.6 ± 26.2 | 53.0 ± 19.7 | 46.3 ± 15.9 |

| Smoke free, yr | N/A | 8.8 ± 6.1 | 5.3 ± 3.0 | 9.6 ± 5.7 | 8.1 ± 6.5 | 5.5 ± 4.5 |

| Number of airways examined | 274 | 258 | 93 | 185 | 105 | 189 |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; N/A = data not applicable; UCSF = University of California, San Francisco; VUMC = Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Median (range) for spirometry data (available for four former smokers without COPD who underwent lung resection for solitary tumors and all former smokers with COPD).

Mean ± SD is indicated for age and smoking. All former smokers without COPD and patients with COPD included in this study had abstained from smoking for >1 year.

P < 0.05 compared with subjects without COPD and subjects with GOLD stage III or IV COPD.

Airway Histology, Immunohistochemistry, and In Situ Hybridization

Paraffin sections (5 μm) were cut from each tissue specimen and serial sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for routine histologic evaluation, periodic acid–Schiff staining for detection of mucin, and Masson trichrome for analysis of fibrous remodeling. Additional serial sections were used for the following studies: (1) immunofluorescence microscopy using primary mouse monoclonal antibodies directed against IgA (#ab17747; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and secondary antibodies labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (#711-095-152; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory, West Grove, PA); (2) fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) with a conserved bacterial 16S rRNA gene probe (Cy3-GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-Cy3) combined with immunostaining with primary mouse monoclonal antibodies against IgA (Abcam) and secondary antibodies labeled with FITC (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory); (3) dual immunostaining using primary antibodies against IgA (mouse monoclonal; Abcam) and the phosphorylated p65 subunit of nuclear factor (NF)-κB (#sc101749, phospho-p65, Ser276, rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) with secondary antibodies labeled with FITC and Cy3, respectively (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory); and (4) immunostaining with primary antibodies against neutrophil elastase (#GTX72699; GeneTex, Irvine, CA) or CD68 (#ab49777; Abcam) using a standard immunoperoxidase/avidin-biotin complex protocol (Vectastain ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) to detect neutrophils and macrophages, respectively. The specificity of immunohistochemistry was verified using an isotype control antibodies by replacing the primary antiserum with an identical concentration of nonimmunized mouse or rabbit serum (Invitrogen Corporation, Camarillo, CA). For detection of bacterial DNA by FISH, we followed the published protocol by Canny and colleagues (18) using a probe purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA).

Small airways (diameter <2 mm) were identified in each hematoxylin and eosin–stained tissue section and assigned an identification number. Each airway was then identified in serial tissue sections and examined for epithelial remodeling, IgA expression on the mucosal surface, presence of bacterial DNA between the airway surface and the basement membrane, phospho-p65 expression in airway epithelial cells, leukocyte accumulation, and wall remodeling.

Morphometry

To quantify IgA on the airway surface, we measured the IgA-specific fluorescent signal using our previously described method (14). Briefly, one tissue section from each tissue block was immunostained with primary antibodies against IgA using fluorescent labeling (FITC). Digital images of individual small airways were captured with the same magnification (×10 objective) and the same digital camera settings. Intensity of IgA-specific fluorescent signal was measured as actual pixel value (apv) using the Line Profile function (intensity values of a single perpendicular line crossing the mucosal layer) at eight spots equally spaced along the circumference of the epithelial surface at 45-degree angles. The average intensity value of each individual airway was then reported. To test for reproducibility of this measurement, we performed immunostaining on three separate occasions using a subset of five control subjects. In addition to consistently classifying each airway as SIgA intact or SIgA deficient, reproducibility of these apv measurements was further assessed by determining the intraclass correlation coefficient, which we estimated using a mixed effect model to account for triplicate measurements from multiple airways per subject. We determined an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.67, which has been considered good reproducibility (19).

Neutrophils were enumerated within the airway wall between the basement membrane and the outer edge of adventitia, whereas macrophages were enumerated within 0.5 mm of the outer edge of adventitia. Cell numbers were normalized to the length of basement membrane for each individual airway. Airway wall remodeling was evaluated by measurement of subepithelial connective tissue volume density (VVairway), which is defined as the difference between the area delineated by the basement membrane and the outer edge of the airway adventitia, divided by the length of the subepithelial basement membrane (14). All morphometric measurements were made using Image-Pro Plus 7.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Springs, MD).

Statistical Analysis

All data from human subjects were included in the statistical analyses. Clinical characteristics of research subjects are presented as mean ± SD or frequency as appropriate. Experimental results are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. We conducted analyses of small airways at two levels: comparisons among mean values for individual research subject in four different groups (lifelong nonsmokers, former smokers without COPD, subjects with COPD stage I–II, and subjects with COPD stage III–IV); and comparisons among values from all airways per study group. Comparisons among mean values for individual subjects were performed using analysis of variance or nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. If differences were observed among subject groups, we then performed pair-wise comparisons among prespecified subject groups with Bonferroni corrected two-sided significance level of 0.05. Comparisons at the airway level were analyzed using a linear mixed effect model if measurements were continuous or a mixed effect logistic regression model if measurements were dichotomous. The mixed effect models took into consideration that each subject contributed multiple airways. Normality of residuals of both analysis of variance and linear mixed effect models were diagnosed and transformation on the dependent variable was done to correct nonnormal residuals if needed. To assess the relationship between IgA-specific fluorescence on the surface of individual airways and measurements of airway wall thickness and inflammatory cell influx, we also plotted the locally weighted scatter plot smoother (LOESS) curve to illustrate these relationships. In studies where we characterized each airway based on the structure of the lining epithelium, we compared the proportion of airways in each of four categories among subject groups using a Dirichlet regression model (20). The Dirichlet regression model takes into consideration that the proportion of each type of airway (based on epithelial structure) from an individual subject is bounded between 0 and 1 and summed up to 1. All analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) and R-software version 3.1.2 (www.r-project.org). P less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Small Airway Inflammation and Remodeling Are Increased in COPD

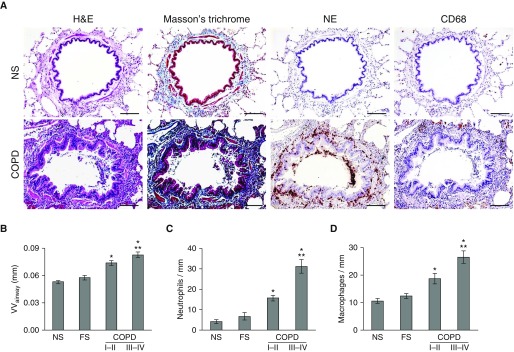

We analyzed 1,104 small airways (<2 mm in diameter) that were present on lung tissue sections obtained from 50 former smokers with COPD and 39 lifelong nonsmokers or former smokers without COPD (Table 1). We limited our studies to lifelong nonsmokers and former smokers to ensure that the changes we observed were not related to acute effects of cigarette smoke exposure. Initially, we investigated whether parameters of airway inflammation and airway wall remodeling were increased in lungs of patients with COPD and correlated with disease severity. We measured subepithelial VVairway as an indicator of airway wall thickness/remodeling and determined inflammatory cell influx by counting neutrophils and macrophages in and around small airways. By comparing the mean airway wall thickness and inflammatory cell counts from each study participant, we found an increase in airway wall thickness and leukocyte accumulation in patients with COPD with mild-moderate disease (GOLD stage I–II) compared with lifelong nonsmokers and former smokers without COPD (Figure 1). These parameters were further increased in patients with severe–very severe COPD (GOLD stage III–IV).

Figure 1.

Inflammation and remodeling of small airways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) correlate with disease severity. (A, top) Representative small airway from a lifelong nonsmoker without COPD showing normal-appearing structural organization with few neutrophils within subepithelium or macrophages in peribronchial airspace. (A, bottom) Small airway from a former smoker with COPD with increased wall thickness/remodeling and inflammation. Images in each row represent the same airways identified on serial tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Masson trichrome, antibodies against neutrophil elastase for identification of neutrophils, and anti-CD68 antibodies for macrophages. Scale bars = 100 µm. (B) Mean airway wall thickness for each subject from the following groups: 24 lifelong nonsmokers, 15 former smokers without COPD, 20 patients with Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage II–III COPD, and 30 patients with GOLD stage III–IV COPD. (C) Mean neutrophil and (D) mean macrophage counts for each subject, normalized for length of basement membrane. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Groups were compared using analysis of variance and a Bonferroni post-test to correct for four separate comparisons among the subject groups. *Significantly different compared with NS. **Significantly different compared with GOLD stage I–II COPD. FS = former smoker without COPD; H&E = hematoxylin and eosin; NE = neutrophil elastase; NS = lifelong nonsmoker without COPD; VVairway = mean airway wall thickness.

Airway Epithelial Remodeling in COPD Is Associated with Localized SIgA Deficiency

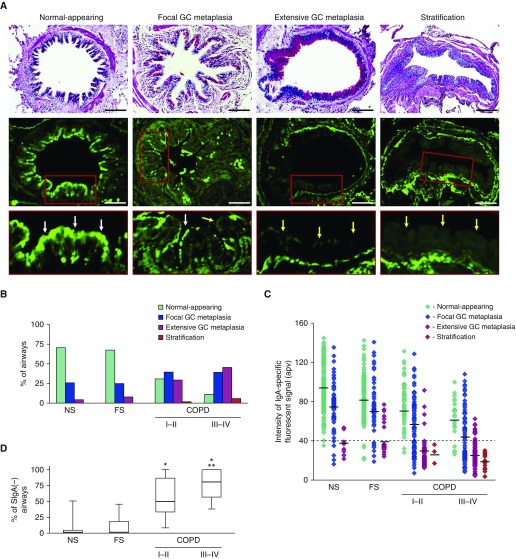

Histologic analysis of small airways identified four distinct patterns of epithelial structure: (1) normal-appearing epithelium, (2) focal goblet cell metaplasia (involving <25% of the epithelial surface), (3) extensive goblet cell metaplasia (involving >25% of the epithelial surface), and (4) stratification (Figure 2A, top). The distribution of these four epithelial patterns varied among the different groups of subjects. In lifelong nonsmokers and former smokers without COPD, most airways were covered by normal-appearing epithelium or focal goblet cell metaplasia. In contrast, subjects with COPD I–II or COPD III–IV had a significantly higher proportion of airways with extensive goblet cell metaplasia or stratification (P < 0.01) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Epithelial remodeling is common in small airways from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and is associated with loss of secretory IgA (SIgA) on the luminal surface. (A) Small airways with different epithelial morphologies including normal-appearing, focal goblet cell (GC) metaplasia (involving <25% of the epithelial surface), extensive GC metaplasia (involving >25% of the epithelial surface), and stratification (top). Periodic acid–Schiff stain, scale bars = 100 µm. Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy for anti-IgA antibody (green, middle). Insets with white arrows show SIgA on mucosal surface and yellow arrows denote mucosal surface in SIgA-deficient airways (bottom). (B) Distribution of epithelial morphology in all small airways examined from lifelong nonsmokers, former smokers without COPD, former smokers with Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage I–II COPD, and former smokers with GOLD stage III–IV COPD. The percentage of airways with extensive GC metaplasia or stratification is increased in subjects with COPD (P < 0.01 by Dirichlet regression model). (C) Levels of IgA-specific fluorescence on the luminal surface of each small airway plotted by epithelial morphology. Mean actual pixel value for each epithelial subtype in each group is indicated. Dashed line indicates the cutoff for classifying airways as SIgA(+) or SIgA(−). (D) Box-and-whisker plot showing median, 25th–75th percentile, and range for the percentage of SIgA(−) airways in each group of subjects. Groups were compared using a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Mann-Whitney U tests for four prespecified pair-wise comparisons (significance level was Bonferroni adjusted at 0.0125). *Significantly different compared with nonsmoker. **Significantly different compared with GOLD stage I–II COPD. apv = actual pixel value; FS = former smoker; NS = nonsmoker.

We next assessed the relationship between epithelial remodeling and SIgA levels on the airway surface by fluorescence immunostaining of lung sections with anti-IgA antibodies. In small airways covered by epithelium classified as normal-appearing or focal goblet cell metaplasia, the airway epithelium was covered by a thin layer of SIgA. In contrast, SIgA was markedly reduced on the apical epithelial surface of airways with extensive goblet cell metaplasia and stratification (Figure 2A, middle and bottom). After controlling for background fluorescence using a nonimmune mouse serum (see Figure E1 in the online supplement), we quantified the fluorescent intensity of IgA staining on the airway surface and plotted values for fluorescent intensity for each airway based on the appearance of the overlying epithelium (Figure 2C). We then chose a value of 40 apv (which was near the lower limit of IgA intensity for normal-appearing airways) to categorize small airways as SIgA intact (SigA[+]) or SIgA deficient (SigA[−]). As shown in Figure 2D, SIgA-deficient small airways were rare in subjects without COPD (median, 0%; interquartile range [IQR], 0–4.3% for SigA[−] small airways in lifelong nonsmokers) (median, 0%; IQR, 0–18.3% for former smokers without COPD) but common in small airways of patients with COPD (median SigA[−] airways, 50%; IQR, 33.3–86.7% in COPD I–II) (median, 80%; IQR, 56.7–100% in COPD III–IV). Thus, localized SIgA deficiency on the surface of small airways is frequently found in patients with COPD in association with structural changes to the epithelium.

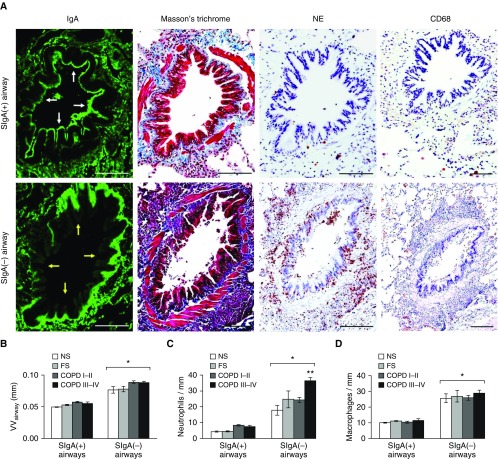

Airway Surface Deficiency of SIgA Correlates with Airway Wall Remodeling and Localized Inflammation

After identifying SIgA(+) and SIgA(−) airways, we compared measurements of airway wall thickness (VVairway) and inflammatory cell influx in each individual airway based on the SIgA classification (Figure 3A). We found that SIgA(−) airways had increased airway wall thickening and increased inflammatory cell counts compared with SIgA(+) airways, irrespective of subject group (Figures 3B–3D; see Figure E2). For neutrophils, we observed the greatest numbers of cells in SIgA(−) airways from the COPD III–IV subjects (Figure 3C; see Figure E2).

Figure 3.

Airway surface secretory IgA (SIgA) deficiency is associated with fibrotic remodeling of the airway wall and inflammatory cell accumulation. (A) SIgA(+) small airway from patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) without signs of wall thickness/remodeling and inflammation (top). SIgA(−) small airway from the same patient with COPD with increased wall thickness/remodeling and inflammation (bottom). Each row of images represents the same airways identified on serial tissue sections with immunofluorescent staining for IgA, Masson trichrome staining, and immunostaining for neutrophil elastase and CD68. White arrows indicate the apical epithelial border of a SIgA(+) airway; yellow arrows indicate the apical epithelial border of a SIgA(−) airway. Scale bars = 100 µm. (B) Mean airway wall thickness for SIgA(+) and SIgA(−) airways from each subject according to patient group (nonsmoker, former smoker, COPD I–II, COPD III–IV). (C and D) Mean numbers of neutrophils and macrophages for SIgA(+) and SIgA(−) airways from each subject, normalized to basement membrane length. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. A mixed effect model was conducted to compare the difference between SIgA(+) and SIgA(−) airways and across subject groups. *Significantly different compared with SIgA(+) airways. **Significantly different compared with other groups of SIgA(−) airways. FS = former smoker; NE = neutrophil elastase; NS = nonsmoker; VVairway = mean airway wall thickness.

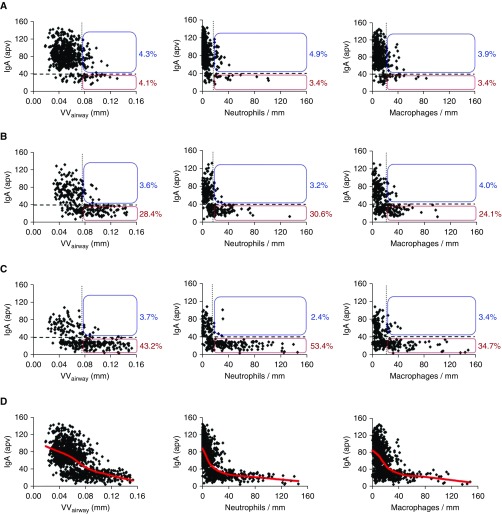

Next, we identified airways with pathologic fibrotic remodeling and inflammation based on a cutoff of 2 SD above the mean value for airway wall thickness (VVairway) and neutrophil/macrophage counts in airways from the lifelong nonsmoker group. In lungs of patients with COPD, we observed that the increased proportion of pathologically remodeled/inflamed airways was associated with expansion of the subset of SIgA(−) airways (Figures 4A–4C). In control subjects without COPD, 8.4% of airways had pathologic airway wall remodeling as defined previously (4.3% were SigA[+] and 4.1% SigA[−]). In contrast, 32.0% of airways from patients with stage I–II COPD and 46.9% of airways from patients with stage III–IV COPD had pathologic wall thickening, and this increase was observed primarily in SIgA(−) airways. Similar findings were observed for neutrophil and macrophage counts. In control subjects, 8.3% of airways had increased neutrophil infiltration (4.9% were SigA[+] and 3.4% SigA[−]), whereas 33.8% of airways had increased neutrophils in stage I–II COPD and 55.8% of airways had increased neutrophils in stage III–IV COPD. Increased macrophage accumulation surrounding these airways was observed in 7.3% of control airways (3.9% were SigA[+] and 3.4% SigA[−]), whereas 28.1% and 38.1% of airways in stage I–II COPD and stage III–IV COPD, respectively, had increased macrophage infiltration. For both of these inflammatory cell parameters, the increase in patients with COPD was primarily detected in SIgA(−) airways. When all groups of subjects were combined, we observed a significant inverse correlation between SIgA intensity on the airway surface and airway wall thickness, neutrophil infiltration, and macrophage accumulation (Figure 4D). Together, these data show a close relationship between SIgA status of individual airways and parameters of remodeling and inflammation, independent of disease state.

Figure 4.

Airway wall thickness and leukocyte accumulation are associated with the secretory IgA (SIgA) status of individual small airways. (A–C) IgA-specific fluorescence intensity plotted against airway wall thickness (VVairway), neutrophil counts, and macrophage counts for each individual small airway. Airways from lifelong nonsmokers and former smokers without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were combined as a control group. The horizontal dashed line represents the cutoff for classifying airways as SIgA(+) or SIgA(−); vertical dotted line in each graph represents 2 SD above the mean for the control group. Boxes show the percentage of SIgA(+) and SIgA(−) airways with increased VVairway, neutrophils, or macrophage counts as defined previously. (D) Correlation of IgA-specific fluorescence on the surfaces of individual small airways and VVairway, neutrophil counts, and macrophage counts for all 1,104 airways. apv = actual pixel value. Red line represents the LOESS (locally weighted scatter plot smoother) curve for each scatterplot. A mixed effect model was used to identify a significant inverse relationship (P < 0.001) between IgA-specific fluorescence and VVairway, neutrophils, and macrophages. (A) Control subjects; (B) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) I–II; (C) COPD III–IV; (D) combined (nonsmokers, former smokers, and COPD).

Bacterial Invasion into the Airway Epithelium and Activation of the NF-κB Pathway Are Associated with SIgA Deficiency in Individual Small Airways

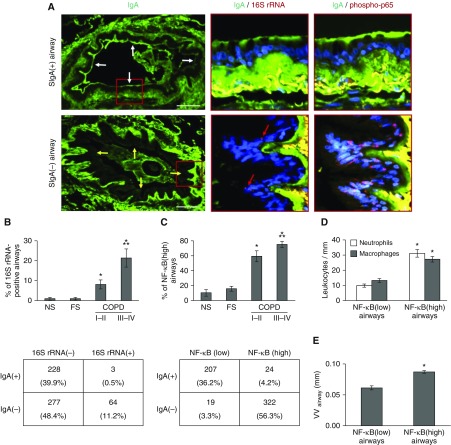

To explain the chronic inflammation observed in SIgA(−) airways, we postulated that loss of the SIgA barrier could allow increased contact between colonizing bacteria and airway epithelial cells. Therefore, we analyzed lung specimens for bacterial DNA in small airways by FISH using a probe for the conserved portion of the bacterial gene encoding 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) (Figure 5A). Compared with individuals without COPD, small airways from patients with COPD were much more likely to contain detectable bacterial DNA, with the highest proportion of bacterial DNA containing airways in COPD III–IV subjects (Figure 5B). When airways of patients with COPD were analyzed based on SIgA status, bacteria were virtually undetectable in the epithelial layer of SIgA(+) small airways (<1%), whereas 11.2% of SIgA(−) small airways in cross-section contained bacterial DNA within the epithelial layer (adjusted odds ratio, 0.06; 95% confidence interval, 0.01–0.16 comparing SigA[+] with SigA[−] airways) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Bacterial invasion of the bronchial mucosa and activation of the nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway is localized to secretory IgA (SIgA)(−) airways. (A) Immunofluorescence staining for IgA on the epithelial surface of an SIgA(+) airway and an SIgA(−) airway from the same patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Red boxes indicate areas shown in panels to the right. Serial sections show IgA (green) and bacterial DNA identified by fluorescent in situ hybridization with a 16S rRNA gene probe (red, indicated by arrows). Bacteria are intercalated within the airway epithelium of the SIgA(−) airway, but no bacterial DNA is identified in the SIgA(+) airway. Additional sections show IgA (green) and immunofluorescent detection of phospho-p65 (Ser276) in the nucleus (red) as an indicator of NF-κB activation. The yellow areas below the basement membrane represent autofluorescence of collagen bundles. White arrows indicate the apical epithelial border of a SIgA(+) airway; yellow arrows indicate the apical epithelial border of a SIgA(−) airway. Scale bars = 100 µm. (B) Mean percentage of airways positive for 16S bacterial DNA for each individual in each group of subjects. Groups were compared using analysis of variance and a Bonferroni post-test to correct for four separate comparisons among the subject groups. *Significantly different compared with nonsmoker. **Significantly different compared with COPD I–II. The table illustrates the distribution of 572 airways in all 50 subjects with COPD based on the presence or absence of bacterial DNA within the epithelial lining according to SIgA status. (C) Mean percentage of NF-κB(high) airways (defined as >5% of epithelial cells positive for nuclear phospho-p65) for each individual in each group of subjects. Groups were compared using analysis of variance and a Bonferroni post-test to correct for four separate comparisons among the subject groups. *Significantly different compared with nonsmoker. **Significantly different compared with COPD I–II. The table shows the distribution of airways in subjects with COPD based on NF-κB activation and SIgA status. (D) Mean numbers of leukocytes (neutrophils or macrophages) normalized to basement membrane length from small airways in lung sections from each patient with COPD based on NF-κB activation status (NF-κB[low] or NF-κB[high]). (E) Mean airway wall thickness measurements normalized to basement membrane length from small airways in lung sections from each patient with COPD based on NF-κB activation status. A mixed effect model was conducted to compare the difference between NF-κB(low) and NF-κB(high) airways. *Significantly different compared with NF-κB(low) airways. FS = former smoker; NS = nonsmoker; VVairway = mean airway wall thickness.

Bacteria can initiate innate immune signaling in the epithelium through activation of Toll-like receptors, leading to activation of the NF-κB pathway (21–23). To investigate whether airway surface SIgA deficiency and the presence of bacteria within the epithelial layer correlate with NF-κB activation, we performed fluorescent immunostaining for an activated form of the RelA(p65) component of NF-κB (phosphoserine 276 [24–26]) on serial sections (Figure 5A). Airways were classified as NF-κB(low) or NF-κB(high) if less than or equal to 5% or greater than 5% of epithelial cells showed nuclear staining for phospho-p65 (Ser276). As shown in Figure 5C, the percentage of NF-κB(high) airways was increased in patients with COPD and phospho-p65 staining was strongly associated with airway surface SIgA status. Whereas only 10.4% of SIgA(+) airways were NF-κB(high), 94.4% of SIgA(−) airways were NF-κB(high) (adjusted odds ratio, 0.003; 95% confidence interval, 0.001–0.010 comparing SigA[+] with SigA[−] airways) (Figure 5C). In addition to bacterial DNA, NF-κB(high) airways from patients with COPD contained more inflammatory cells and showed more fibrotic airway wall remodeling than NF-κB(low) airways (Figures 5D and 5E). Collectively, these data support a connection between SIgA deficiency on the surface of small airways, bacterial penetration across the epithelial barrier, and activation of NF-κB signaling.

Discussion

Despite smoking cessation, many patients with COPD have persistent inflammation and progression of disease. In fact, cross-sectional studies of former smokers with COPD demonstrate airway inflammation comparable to that of current smokers with COPD (27–31). Our data show a close correlation between altered mucosal immunity and key histologic parameters of inflammation and remodeling in small airways from former smokers with COPD. SIgA deficiency is common on the mucosal surface of small airways in COPD, and these airways show abnormalities in epithelial morphology, increased susceptibility to bacterial invasion, NF-κB pathway activation, accumulation of neutrophils and macrophages, and airway wall thickening. In contrast, airways with intact SIgA on the mucosal surface show none of these findings, regardless of disease status. Together, these results suggest that abnormalities of small airway epithelium disrupt the mucosal immune barrier by reducing transcytosis of IgA to the airway surface, allowing microorganisms and other inflammatory stimuli (e.g., inhaled particulates) to penetrate the luminal epithelium, thereby promoting chronic inflammation, which in turn perpetuates small airway dysfunction and remodeling, even in the absence of ongoing cigarette smoke exposure.

Based on our classification system, SIgA-deficient airways comprise a small proportion of the total small airways in lifelong nonsmokers and former smokers without COPD. In contrast, approximately 50% of small airways from patients with mild-moderate COPD and approximately 80% of small airways from patients with severe–very severe COPD were classified as SIgA deficient. SIgA-deficient airways appeared similar regardless of disease status, suggesting that disease progression in COPD is more closely related to an increased proportion of SIgA(−) airways rather than progressive pathologic changes in individual diseased airways.

Transcytosis of IgA across the epithelium is limited by expression of pIgR (12, 32). In airway and intestinal mucosa, pIgR expression is regulated by several factors, including proinflammatory cytokines that induce pIgR expression and neutrophil serine proteases that cleave and inactivate pIgR (33–35). Our previous (14) and current data suggest that only normally differentiated airway epithelium expresses sufficient pIgR to maintain an intact immune barrier. Thus, the widespread epithelial abnormalities seen in COPD airways are likely responsible for reduced pIgR expression and insufficient delivery of SIgA to the surface of individual small airways (14). These results support the idea that persistent structural and functional abnormalities of airway epithelium play an important role in development and progression of COPD.

Studies have shown that the lung microbiome is complex and dynamic in healthy individuals and is altered in patients with COPD (36–41). Normally, inhaled or aspirated microorganisms are quickly agglutinated by SIgA and then removed via mucociliary clearance (42–44). Our data suggest that impairment of the epithelial immune barrier allows bacteria (and possibly other foreign antigens) to penetrate the airway surface liquid, intercalate within the epithelium, and activate innate immune responses. Given that increased numbers of bacteria were identified within the epithelium of SIgA(−) airways in humans and COPD-like lung remodeling is abrogated in pIgR-deficient mice raised in germ-free housing (17), our findings suggest that long-term interventions to reduce or modify the bacterial burden in the lungs could have a beneficial impact on COPD progression.

Although leukocytes can protect the host by destroying microorganisms, these cells can also exacerbate lung tissue damage in COPD (45–47). Accumulation of activated neutrophils and macrophages has long been suggested to be important pathogenetic factors in COPD (48, 49). Their products, including neutrophil elastase and matrix metalloproteinase-12, can cause proteolytic damage to lung tissue (45, 50–52), leading to fibrotic airway wall remodeling and emphysema. Based on our findings, we propose that localized impairment of the mucosal immune barrier in individual small airways represents a critical step in an immunopathologic process that drives disease progression.

Although we acknowledge the limited ability to assign causality in pathologic studies involving human tissue, our findings support the concept that local mucosal immune deficiency contributes to COPD pathogenesis. This study is complementary to our recently published work showing that mice with a defective SIgA immune system in the lungs develop a COPD-like phenotype as they age with airway wall remodeling, an influx of macrophages and neutrophils, bacterial invasion across the epithelial barrier, and activation of NF-κB (17). All these findings were manifest in SIgA(−) airways in humans. Importantly, the COPD-like phenotype in pIgR-deficient mice continues to worsen with aging, indicating that injury and remodeling caused by pIgR/SIgA deficiency are additive and progressive. Together, these data from humans with COPD and our recently published mouse model indicate that mucosal immune deficiency with reduced SIgA on the surface of small airways is a driver of chronic inflammation and disease progression in COPD, even in the absence of ongoing cigarette smoke exposure.

In conclusion, this work illuminates the importance of airway epithelium in normal mucosal host defense and coordinating interactions between the SIgA immune system (which typically eliminates airborne antigens and microorganisms) and innate immunity (which is normally reserved as a second line of mucosal host defense). Innovative approaches to restore the mucosal immune barrier in small airways could result in new disease-modifying treatments for patients with COPD.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH NHLBI HL092870, HL085317, HL105479, T32 HL094296, and NIH HL126176), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000445), American Lung Association (RT-309491), Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award (1l01BX002378), and Forest Research Institute grant (DAL-IT-07).

Author Contributions: P.P.M., L.B.W., and J.W.L. provided human lung samples. V.V.P. and R.-H.D. conducted immunostainings and fluorescent in situ hybridization. V.V.P. conducted histologic analysis and morphometry. P.W. and H.N. provided statistical support. B.W.R., J.M.C., W.E.L., and A.V.K. provided scientific and technical knowledge. V.V.P. and T.S.B. cosupervised the project, conducted overall design of the project and construction of the article, and wrote the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0759OC on December 2, 2016

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Fabbri LM, Martinez FJ, Nishimura M, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:347–365. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.2014 Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Revised 2014. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) [accessed 2014 Jan 23]. Available from: www.goldcopd.org.

- 3.Celli BR, Decramer M, Wedzicha JA, Wilson KC, Agustí A, Criner GJ, MacNee W, Make BJ, Rennard SI, Stockley RA, et al. ATS/ERS Task Force for COPD Research. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Research questions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:e4–e27. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201501-0044ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogg JC, Macklem PT, Thurlbeck WM. Site and nature of airway obstruction in chronic obstructive lung disease. N Engl J Med. 1968;278:1355–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196806202782501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanai M, Sekizawa K, Ohrui T, Sasaki H, Takishima T. Site of airway obstruction in pulmonary disease: direct measurement of intrabronchial pressure. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1992;72:1016–1023. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.3.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, Cherniack RM, Rogers RM, Sciurba FC, Coxson HO, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2645–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgel PR. The role of small airways in obstructive airway diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20:23–33. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00010410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonough JE, Yuan R, Suzuki M, Seyednejad N, Elliott WM, Sanchez PG, Wright AC, Gefter WB, Litzky L, Coxson HO, et al. Small-airway obstruction and emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1567–1575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao W, Li L, Wang Y, Zhang S, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ, Huang M, Yao X. Bronchial epithelial cells: the key effector cells in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Respirology. 2015;20:722–729. doi: 10.1111/resp.12542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiemstra PS, McCray PB, Jr, Bals R. The innate immune function of airway epithelial cells in inflammatory lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:1150–1162. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00141514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight DA, Holgate ST. The airway epithelium: structural and functional properties in health and disease. Respirology. 2003;8:432–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilette C, Ouadrhiri Y, Godding V, Vaerman JP, Sibille Y. Lung mucosal immunity: immunoglobulin-A revisited. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:571–588. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00228801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilette C, Godding V, Kiss R, Delos M, Verbeken E, Decaestecker C, De Paepe K, Vaerman JP, Decramer M, Sibille Y. Reduced epithelial expression of secretory component in small airways correlates with airflow obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:185–194. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.9912137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polosukhin VV, Cates JM, Lawson WE, Zaynagetdinov R, Milstone AP, Massion PP, Ocak S, Ware LB, Lee JW, Bowler RP, et al. Bronchial secretory immunoglobulin a deficiency correlates with airway inflammation and progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:317–327. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1629OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du RH, Richmond BW, Blackwell TS, Jr, Cates JM, Massion PP, Ware LB, Lee JW, Kononov AV, Lawson WE, Blackwell TS, et al. Secretory IgA from submucosal glands does not compensate for its airway surface deficiency in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Virchows Arch. 2015;467:657–665. doi: 10.1007/s00428-015-1854-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gohy ST, Detry BR, Lecocq M, Bouzin C, Weynand BA, Amatngalim GD, Sibille YM, Pilette C. Polymeric immunoglobulin receptor down-regulation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Persistence in the cultured epithelium and role of transforming growth factor-β. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:509–521. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201311-1971OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richmond BW, Brucker RM, Han W, Du RH, Zhang Y, Cheng DS, Gleaves L, Abdolrasulnia R, Polosukhina D, Clark PE, et al. Airway bacteria drive a progressive COPD-like phenotype in mice with polymeric immunoglobulin receptor deficiency. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11240. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canny G, Swidsinski A, McCormick BA. Interactions of intestinal epithelial cells with bacteria and immune cells: methods to characterize microflora and functional consequences. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;341:17–35. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-113-4:17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6:284–290. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maier MJ. DirichletReg: Dirichlet regression for compositional data in R. Research Report Series, Report 125. January 18, 2014. Available from: http://statmath wu ac at/

- 21.Dev A, Iyer S, Razani B, Cheng G. NF-κB and innate immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;349:115–143. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawasaki T, Kawai T. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Front Immunol. 2014;5:461. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oviedo-Boyso J, Bravo-Patino A, Baizabal-Aguirre VM. Collaborative action of Toll-like and Nod-like receptors as modulators of the inflammatory response to pathogenic bacteria. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:432785. doi: 10.1155/2014/432785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vermeulen L, De Wilde G, Van Damme P, Vanden Berghe W, Haegeman G. Transcriptional activation of the NF-kappaB p65 subunit by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (MSK1) EMBO J. 2003;22:1313–1324. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darb-Esfahani S, Sinn BV, Weichert W, Budczies J, Lehmann A, Noske A, Buckendahl AC, Müller BM, Sehouli J, Koensgen D, et al. Expression of classical NF-kappaB pathway effectors in human ovarian carcinoma. Histopathology. 2010;56:727–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Law M, Corsino P, Parker NT, Law BK. Identification of a small molecule inhibitor of serine 276 phosphorylation of the p65 subunit of NF-kappaB using in silico molecular docking. Cancer Lett. 2010;291:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rutgers SR, Postma DS, ten Hacken NH, Kauffman HF, van Der Mark TW, Koëter GH, Timens W. Ongoing airway inflammation in patients with COPD who do not currently smoke. Thorax. 2000;55:12–18. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_1.262s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willemse BW, ten Hacken NH, Rutgers B, Lesman-Leegte IG, Postma DS, Timens W. Effect of 1-year smoking cessation on airway inflammation in COPD and asymptomatic smokers. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:835–845. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00108904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lapperre TS, Postma DS, Gosman MM, Snoeck-Stroband JB, ten Hacken NH, Hiemstra PS, Timens W, Sterk PJ, Mauad T. Relation between duration of smoking cessation and bronchial inflammation in COPD. Thorax. 2006;61:115–121. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.040519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lapperre TS, Sont JK, van Schadewijk A, Gosman MM, Postma DS, Bajema IM, Timens W, Mauad T, Hiemstra PS GLUCOLD Study Group. Smoking cessation and bronchial epithelial remodelling in COPD: a cross-sectional study. Respir Res. 2007;8:85. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tashkin DP, Murray RP. Smoking cessation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2009;103:963–974. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brandtzaeg P. Induction of secretory immunity and memory at mucosal surfaces. Vaccine. 2007;25:5467–5484. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pilette C, Ouadrhiri Y, Dimanche F, Vaerman JP, Sibille Y. Secretory component is cleaved by neutrophil serine proteinases but its epithelial production is increased by neutrophils through NF-kappa B- and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent mechanisms. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:485–498. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ratajczak C, Guisset A, Detry B, Sibille Y, Pilette C. Dual effect of neutrophils on pIgR/secretory component in human bronchial epithelial cells: role of TGF-beta. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010. p. 428618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Johansen FE, Kaetzel CS. Regulation of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor and IgA transport: new advances in environmental factors that stimulate pIgR expression and its role in mucosal immunity. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:598–602. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang YJ, Sethi S, Murphy T, Nariya S, Boushey HA, Lynch SV. Airway microbiome dynamics in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:2813–2823. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00035-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui L, Morris A, Huang L, Beck JM, Twigg HL, III, von Mutius E, Ghedin E. The microbiome and the lung. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:S227–S232. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201402-052PL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aguirre E, Galiana A, Mira A, Guardiola R, Sánchez-Guillén L, Garcia-Pachon E, Santibañez M, Royo G, Rodríguez JC. Analysis of microbiota in stable patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. APMIS. 2015;123:427–432. doi: 10.1111/apm.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin C, Burgel PR, Lepage P, Andréjak C, de Blic J, Bourdin A, Brouard J, Chanez P, Dalphin JC, Deslée G, et al. Host-microbe interactions in distal airways: relevance to chronic airway diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24:78–91. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00011614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen LD, Viscogliosi E, Delhaes L. The lung mycobiome: an emerging field of the human respiratory microbiome. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:89. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sze MA, Dimitriu PA, Suzuki M, McDonough JE, Campbell JD, Brothers JF, Erb-Downward JR, Huffnagle GB, Hayashi S, Elliott WM, et al. Host response to the lung microbiome in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:438–445. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201502-0223OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brandtzaeg P. Role of secretory antibodies in the defense against infections. Int J Med Microbiol. 2003;293:3–15. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woof JM, Kerr MA. The function of immunoglobulin A in immunity. J Pathol. 2006;208:270–282. doi: 10.1002/path.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corthésy B. Roundtrip ticket for secretory IgA: role in mucosal homeostasis? J Immunol. 2007;178:27–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoenderdos K, Condliffe A. The neutrophil in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48:531–539. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0492TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holloway RA, Donnelly LE. Immunopathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:95–102. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835cfff5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stewart JI, Criner GJ. The small airways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: pathology and effects on disease progression and survival. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:109–115. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835ceefc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schleimer RP. Innate immune responses and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: “Terminator” or “Terminator 2”? Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:342–346, discussion 371–372. doi: 10.1513/pats.200504-030SR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tetley TD. Inflammatory cells and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2005;4:607–618. doi: 10.2174/156801005774912824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Churg A, Wright JL. Proteases and emphysema. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:153–159. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000149592.51761.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lungarella G, Cavarra E, Lucattelli M, Martorana PA. The dual role of neutrophil elastase in lung destruction and repair. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1287–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mocchegiani E, Giacconi R, Costarelli L. Metalloproteases/anti-metalloproteases imbalance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: genetic factors and treatment implications. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17:S11–S19. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000410743.98087.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]