Abstract

Alterations in estrogen-mediated cellular signaling have largely been implicated in the pathogenesis of breast cancer. Here, we investigated the signaling regulation of a splice variant of the estrogen receptor, namely estrogen receptor (ERα-36), associated with a poor prognosis in breast cancers. Coupling in vitro and in vivo approaches we determined the precise sequential molecular events of a new estrogen signaling network in an ERα-negative cell line and in an original patient-derived xenograft. After estrogen treatment, ERα-36 rapidly associates with Src at the level of the plasma membrane, initiating downstream cascades, including MEK1/ERK activation and paxillin phosphorylation on S126, which in turn triggers a higher expression of cyclin D1. Of note, the direct binding of ERα-36 to ERK2 prevents its dephosphorylation by MKP3 and enhances the downstream signaling. These findings improve our understanding of the regulation of non-genomic estrogen signaling and open new avenues for personalized therapeutic approaches targeting Src or MEK in ERα-36-positive patients.

Introduction

Estrogen signaling is essential in the initiation and development of human breast cancers. The biological actions of estrogen are mediated through estrogen receptor ERα and ERβ, which function in the nucleus in a ligand-dependent manner, composed of functional domains,1 including (i) the variable N-terminal A/B domain containing the transactivation domain AF-1, (ii) the C or DNA-binding domain, (iii) the hinge domain (D) and (iv) the E/F domains containing the ligand-binding domain (LBD) and the transactivation domain AF-2.2 Several ERα variants, derived from the alternative mRNA splicing of ESR1 gene, have been reported,3 including ERα-36.4 The transcription of ERα-36 is initiated by a previously unidentified promoter located in the first intron of the ESR1 gene. ERα-36 retains the DNA-binding domain, dimerization faculty and partial LBD, but lacks both AF-1 and AF-2 domains. Furthermore, the last 138 amino-acids, encoded by the final exons 7 and 8 are replaced by an extra unique 27 amino-acid sequence at the C-terminal domain (CTD). ERα-36 is mainly located at the plasma membrane and within the cytoplasm, mediating activation of the ERK pathway (for review see Rao et al.5).

The molecular mechanisms underlying estrogen signaling have been extensively studied for ERs. In addition to the well-documented effects on transcription (genomic signaling), estrogen can activate signal transduction cascades outside of the nucleus (that is, non-genomic signaling).6,7 In this process, ERα interacts directly with various protein kinases to form protein complexes triggering the activation of downstream molecules, such as Akt.8,9 One such complex is the ERα/Src/PI3K complex and our team previously demonstrated that methylation of the receptor on R260 is a prerequisite for its formation.10 Recently, we showed that the ERα/Src/PI3K complex is activated in aggressive breast tumors and could constitute a new potential target for therapy.11 In contrast, although the ERα/Src/PI3K signaling pathway is now well established, relatively little is known on the exact molecular interactions involving ERα-36. Indeed, ERα-36 was shown to activate ERK1/2 through the protein kinase C delta signaling pathway, leading to an increase in the expression of cyclin D1/cdk4, which modulates cell cycle progression.12 Moreover, the ERα-36 signaling pathway contributes to the potential invasion and metastasis of cancer cells,13 and interestingly, ERα-36 is expressed in ERα-negative breast cancer cell lines and ERα-negative tumor samples.14, 15, 16, 17 Intriguingly, ERα-36 can stimulate ERK activation in cells treated with the anti-estrogen tamoxifen,17,18 and is also involved in the development of tamoxifen resistance in ERα-positive breast cancer cell lines.19,20 In ERα-negative breast cancer cell lines, ERα-36 induces paclitaxel resistance through c-jun N-terminal kinases, a component of the ERK family.21

The aim of the present study was to unravel the entire signaling cascade conveyed by ERα-36, in order to identify potentially novel therapeutic targets or adapt existing treatments for breast cancer patients. We determined a new estrogen signaling network in ERα-negative cell lines, involving ERα-36/Src/ERK and PXN (paxillin), which, in turn, regulates cell proliferation via cyclin D1 expression. This signaling pathway was also highlighted in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of breast cancer treated with estrogen, confirming the importance of this signaling pathway in breast cancer.

Results

The functional localization of ERα-36

We initially investigated the functional localization of ERα-36, since although it contains a nuclear localization signal, it is not expressed in the nucleus, unlike ERα (see Rao et al.5). To this end, we submitted the unique CTD of ERα-36 to the NetNES 1.1 prediction server. A putative leucine-rich sequence, homologous to known nuclear export signals (NES) was identified (Supplementary Figures S1a and S1b). We then, either deleted the 27 amino-acids (ERα-36ΔC) or replaced two conserved hydrophobic residues of the NES, namely valine (V288) and leucine (L295) by alanine (A) (Figure 1A). The constructs were transfected into MCF-7 cells and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. As expected, the wild-type (WT) ERα-36 was localized in the cytoplasm and at the level of the plasma membrane (Figure 1Bd-f), whereas the mutants were mainly detected in the nucleus (Figure 1B(g–l)). Hence, our results have uncovered the presence of a functional NES, inducing the exportation of ERα-36 from the nucleus, and able to target the nuclear arginine methyltransferase of type 1 (PRMT1) outside of the nucleus, when it is added at its N-terminus part (Supplementary Figure S1c).

Figure 1.

The molecular properties of ERα-36. (A) Schematic representation of ERα-36 mutants. ERα-36ΔC was generated by deleting the CTD. The NES mutant was obtained by mutating essential hydrophobic residues of the NES. (B) MCF-7 cells were transfected with pSG5Flag vector (a–c), pSG5Flag-ERα-36 (d-f), pSG5Flag-ERα-36ΔC (g-i) or pSG5FlagERα-36 V288A/L295A (j-l) for 36 h, then fixed and stained with DAPI and the anti-Flag antibody. (C) (Left) Modeled structure of the LBD of ERα-36 showing E2 docked in the ligand binding pocket. The proteins homology model is not refined and lacks the C-terminal part of ERα (H10 to H12). The specific sequence of ERα-36 is colored in blue and the ligand in red. The docked E2 forms electrostatic interactions with residues E180 and R221. (Right) The experimental crystal structure of ERα LBD (PDB ID 1A52,41) in complex with E2 is shown for comparison. The CTD which differs from ERα-36 is highlighted in red and the position of the helices 9, 10 and 12 are indicated. (D) HeLa cells were transfected with the pSG5Flag vector, the pSG5Flag-ERα-36 plasmid or the pSG5Flag-ERα-36-E180/A and pSG5Flag-ERα-36-E180/A-R221/A constructs, before E2 activation. A Western blot analysis detected P-ERK, ERK and ERα-36.

The mechanistic interaction between ERα-36 and E2

Since ERα-36 lacks a part of the LBD, we verified, in silico and in cellulo, whether this isoform was able to transduce estrogen-dependent signals. For this purpose, we built homology models of ERα-36 with E2 based on the available crystal structures of ERα LBD complexes. The initial model indicated that two residues, namely glutamic acid (E180) and arginine (R221) (corresponding to E353/R394 in ERα), could anchor the ligand in an open pocket in ERα-36 (Figure 1C). The remaining accessibility of a ligand pocket is in agreement with previous studies, confirming the high level of binding affinity between E2 and ERα-36.22 However, it must be noted that the modifications and truncation of the C-terminal helices in ERα-36 with respect to ERα may alter the conformation of the LBD, an effect that was not modelled, and further studies would be necessary to obtain a high resolution structure of ERα-36 LBD/E2 complex. Next, we generated point mutations of the E180 and R221 residues, replacing them with arginine. We found that overexpression of the WT protein triggered the activation of ERK upon E2 treatment, while the mutants lost this capacity (Figure 1D).

ERα-36 expression in breast tumors

To further investigate the role of ERα-36 in the context of breast cancer, we produced an antibody recognizing the CTD of ERα-36. This antibody was validated by Western blot analyses using (i) GST-ERα-36, (Supplementary Figure S2a), (ii) ER isoforms transfected into HeLa cells (Supplementary Figure S2b), and (iii) CAMA-1 cells, where ERα-36 was knocked down by a siRNA approach (Supplementary Figure S2c). We then evaluated the level of expression of ERα-36 in a panel of human breast cancer cell lines, as well as in PDX models.23 We initially confirmed that ERα-36 is expressed both in ERα-positive and in ERα-negative breast tumors,14, 15, 16, 17 (Supplementary Figures S2d and S2e). One triple negative PDX, namely HBCx-12A, expressed a high level of ERα-36 (Supplementary Figures S2e and S2f), and was thus selected to establish a cell line for future experiments (named HBCc-12A) (Supplementary Figure S2g).

In HBCc-12A cells, E2 triggered a rapid and transient phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Supplementary Figure S2h), though no change in Akt phosphorylation was observed. Furthermore, E2 led to an increase in cell proliferation in vitro (Supplementary Figure S2i) and in vivo (Supplementary Figure S2j).

E2 triggers the interaction of ERα-36 with Src and PI3K kinases

Although the activation of ERK by ERα-36 was previously demonstrated,12,17,24 th,event were not explored. To decipher these mechanisms, we sought to identify the partners of ERα-36, by targeting known ERα partners involved in non-genomic signaling, such as Src and PI3K.8, 10, 25 We initially demonstrated a direct interaction between ERα-36 and both Src and PI3K (Supplementary Figures S3a and S3b), before studying protein-protein interactions using the proximity ligation assay (PLA).26 Upon estrogen treatment, we observed an increase in ERα-36/Src and ERα-36/PI3K interactions in the cytoplasm of HBCc-12A cells (Figure 2A(a–f)), only when using a combination of both antibodies (Figures 2A(g–i) and 2B). Since the methylation of ERα on R260 was shown to trigger its association with Src and PI3K,10 we verified whether such an event occurred with ERα-36, but were unsuccessful (data not shown). Furthermore, since Src and PI3K kinase activities are required for their interaction with ERα,11 we investigated whether they were also required to interact with ERα-36. Treatment of HBCc-12A cells with the Src inhibitor PP1 only abolished the ERα-36/Src interaction, while the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 only inhibited the ERα-36/PI3K interaction (Supplementary Figures S3c and S3d).

Figure 2.

E2 triggers the interaction of ERα-36 with Src, PI3K and P-ERK2. (A and B) HBCc-12A cells were treated with E2 for the indicated times. (A) After fixation, PLA were performed to evaluate the interactions between ERα-36/Src (a–c) or between ERα-36/PI3K dimers (d–f) using ERα-36-, Src- and PI3K-specific antibodies. The detected dimers are represented by red dots. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue) (Obj: X63). Control PLA experiments were performed using single antibodies (g–i). (B) Quantification was performed by counting the number of signals per cell as reported in the Supplementary Material and Methods. The experiment was performed three times, and this graph is representative of one of the experiments. The P-value was determined using the Student's t-test. (C) Sequence alignment of known D domains in selected MAPK substrates aligned with the putative docking site. Basic residues are highlighted in boldface type, and the hydrophobic motif ΦA-X-ΦB is underlined (modified from42). (D) Direct interaction between ERα-36 and ERK2 was analyzed by GST-pull-down experiments. 35S-labeled in vitro translated ERα-36 or ERα-36ΔC was incubated with GST or GST-ERK2. 1/50 of input radiolabeled proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. The right panel shows the corresponding Coomassie-stained gel (E and F) HBCc-12A cells were treated with E2. (E) After fixation, a PLA was performed to evaluate the ERα-36/ERK2 interaction. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (× 63 magnification). (F) The quantification of cells was performed as described in (B). (G–I) HBCc-12A cells were treated or not with the MEK inhibitor, U1026 (10 μM) for 15 min prior to E2 treatment. A PLA was performed to evaluate the ERα-36/ERK2 interaction. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (× 63 magnification). (H) The quantification was performed as described in (B). (I) Cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot for P-ERK and ERK expression. ***P<0.001.

In conclusion, ERα-36 interacts with Src and PI3K but the mechanism involved seems to be different from ERα.

ERα-36 binds specifically to P-ERK2

To identify ERα-36-specific partners, the use of the Scansite software for the CTD uncovered a putative D domain (docking domain) for ERK2 (Figure 2C). We verified the interaction of ERα-36 and ERK2 by GST pull-down and found that this occurs via the CTD (Figure 2D and Supplementary Figure S4a), and in cellulo experiments revealed that this interaction occurs very rapidly in the cytoplasm of the HBCc-12A cells upon the addition of E2 (Figures 2E and F; Supplementary Figure S4b). The use of the MEK inhibitor U1026 abolished the ERα-36/ERK2 interaction (Figures 2G and H), concomitantly with ERK phosphorylation (Figure 2I), suggesting that ERα-36 interacts specifically with P-ERK2. Finally, in vitro phosphorylation assays revealed that ERα-36 is not a substrate for ERK2 (data not shown). An analysis of the 3D structure of ERK2-peptide complexes (Supplementary Table S3 for the list of the complexes) consistently highlighted the essential role of R and L residues in stabilizing the complexes (Supplementary Table S1). Comparison of these data with the ERα-36 CTD sequence demonstrated the implication of a leucine (L297) residue in this interaction, and indicated that the CTD could adopt a structure similar to that seen in existing complexes (Figures 3A for a 3D in silico model representing a putative interaction between the CTD of ERα-36 and ERK2 and Supplementary Table S1). The point mutation of this residue with alanine resulted in an impairment in the interaction (Figure 3B). Furthermore, we disrupted the ERα-36/ERK interaction by transfecting HBCc-12A cells with a Flag-CTD of WT ERα36 or mutated on L297A. We found that the Flag-CTD strongly impaired the E2-induced ERα-36/ERK2 interaction (Figures 3C(d–f) and 3D) compared to the empty vector (Figure 3C(a–c)). Interestingly, the Flag-CTD peptide also completely disrupted ERK phosphorylation (Figure 3E). These effects were not observed in cells transfected with the CTD mutant (Figures 3C(g–i) and 3E). Control immunofluorescence (IF) experiments revealed that Flag-CTD peptides were equally expressed (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Disruption of ERα-36/ERK2 interaction abolishes E2-induced ERK activation. (A) Modeled structure of the ERK2 complex with the CTD of ERα-36. The structure of ERK2 is represented as ribbons, and based the PDB ID 2FYS. The modeled CTD of ERα-36 is represented in red. (B) To study the importance of L297 on ERα-36/ERK2 interaction, a GST pull-down experiment was performed by incubating the GST-ERK2 in the presence of in vitro translated 35S-labeled ERα-36 or ERα-36-L297A mutant (*). 1/50 of input radiolabeled proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. The corresponding Coomassie-stained gel is shown in the right panel. (C–F) The role of the CTD of ERα-36 was investigated by transfecting the HBCc-12A cells were transfected with pSG5-Flag vector, pSG5-Flag-ERα-36-CTD or pSG5-Flag- ERα-36-CTD-L297A for 36 h. The cells were treated with E2 and fixed in methanol. (C) ERα-36/ERK2 interactions were analyzed by PLA. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue) (× 63 magnification). (D) Quantification of the cells was performed as described in Figure 2B. The experiment was performed in triplicate, and this graph is representative of one of the experiments. The P-value was determined using the Student's test. ***P<0.001. (E) P-ERK and ERK were analyzed by Western blot. (F) To verify the efficay of transfection, the cells were fixed and stained with DAPI and anti-Flag antibody.

Taken together these data revealed that the CTD of ERα-36 is essential for ERK phosphorylation.

ERα-36 protects from ERK dephosphorylation by the phosphatase MKP3

We then overexpressed ERα-36 in HBCc-12A cells and found a sustained ERK phosphorylation (beyond 15 min) upon E2 activation (Figure 4A), concomitantly with a sustained ERα-36/ERK2 interaction (Figures 4B and C(e–h)), compared to cells transfected with an empty vector (Figure 4C(a–d)). This effect is specific for ERα-36, since the overexpression of ERα does not have any effect on ERK phosphorylation (Supplementary Figure S5). We hypothesized that ERα-36 could regulate ERK phosphorylation by modulating its dephosphorylation. Since the dual phosphatase MKP3 regulates ERK phosphorylation,27 we knocked down MKP3, and found a sustained ERK phosphorylation upon E2 treatment, demonstrating that MKP3 depletion was sufficient to inhibit ERK dephosphorylation (Figure 4D). This event occurred concomitantly with a sustained ERα-36/ERK2 interaction (Figures 4E and F). We then hypothesized that the binding of ERK2 to ERα-36 could impede its binding to MKP3. In order to verify this hypothesis, we studied ERK2/MKP3 interaction by PLA in HBCc-12A cells transfected with the different Flag-CTD constructs. Interestingly, we found that upon E2 treatment, ERα-36 binds to ERK2 after 5 min while MKP3 binds to ERK2 after 15 min. However, when we disrupted the ERα-36/ERK2 interaction, MKP3 bound to ERK2 within 5 min of treatment (Figures 5A and B). The Flag-CTD L297A mutant displayed similar results to those obtained with the empty vector. Finally, when we overexpressed ERα-36 in HBCc-12A cells (as in Figure 4A), we observed that the ERK2/MKP3 interaction occurred later than in the control cells (Figures 5C and D). Overall, these findings confirm our initial hypothesis that ERα-36 prevents and delays the ERK2/MKP3 interaction, thus leading to a sustained phosphorylation of ERK2.

Figure 4.

Crosstalk between ERα-36 and MKP3 to regulate ERK phosphorylation. (A–C) To determine the role of ERα-36 on ERK signaling, the pSG5-Flag or pSG5-Flag-ERα-36 vectors were transfected into HBCc-12A cells for 36 h prior to E2 activation. (A) The cell extracts were analyzed for the expression of P-ERK, ERK and ERα-36. (B) ERα-36/ERK2 interactions were quantified as described in Figure 2C. The experiment was performed in triplicate, and this graph is representative of one of the experiments. The P-value was determined using the Student's test. ***P<0.001. (C) Cells were used to perform PLA to detect, ERα-36/ERK2 interactions. (D–F) To investigate if MKP3 was the phosphatase involved in regulating ERK phosphorylation, we transfected MCF-7 cells with control siRNA duplexes or with specific MKP3 siRNA duplexes. Next, cell lysates were analyzed for P-ERK, ERK and MKP3 expression. (E) Quantification of the interactions was done as described in (B). (F) Cells were used to perform PLA, as described in (C), to detect ERα-36/ERK2 interactions.

Figure 5.

ERα-36 impedes the interaction between MKP3 and ERK2. To study the role of ERα-36 on ERK2/MKP3 interaction, we overexpressed the CTD of ERα-36 (A and B) or ERα-36 (C and D). (A and B) HBCc-12A cells were transfected with pSG5-Flag vector, pSG5-Flag-ERα-36-CTD or pSG5-Flag-ERα-36-CTD-L297A prior to E2 treatment. (A) A PLA was then conducted to analyze ERK2/MKP3 interactions (× 63 magnification). (B) Quantification was performed as described in Figure 2B. The experiment was performed in triplicate, and this graph is representative of one of the experiments. The P-value was determined using the Student's test. ***P<0.001. (C and D) The pSG5-Flag and pSG5-Flag-ERα-36 vectors were transfected into HBCc-12A cells for 36 h prior E2 treatment. (C) We then analyzed ERK2/MKP3 interactions by PLA as described in (A). (D) Quantification was performed as described in Figure 2B.

The E2/ERα-36 pathway, downstream and upstream of P-ERK

Upon E2 treatment, P-ERK remains exclusively in the cytoplasm of the cells (Figure 6A), so the adaptor paxillin (PXN), which is a cytoplasmic substrate for ERK, was a good candidate.28 We found that upon E2 treatment, the phosphorylation on residue S126 increased rapidly following ERK activation (Figure 6B). We then verified its subcellular localization upon E2 treatment, and found that P-S126-PXN was present exclusively within the nucleus (Figure 6C). It was previously reported that P-S126-PXN can participate in the transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1.29 We therefore studied the expression of cyclin D1 following E2 treatment and observed an increase in cyclin D1 expression after 12 h (Figure 6D). Interestingly, when the pathway was blocked using the MEK inhibitor or when the ERα-36/ERK2 interaction was disrupted, E2 failed to induce PXN phosphorylation and cyclin D1 expression (Figures 6E and F).

Figure 6.

The estrogen signaling pathway downstream of ERK. (A) P-ERK localization was assesed upon E2 treatment. HBCc-12A cells were treated with E2, then fixed and immunostained with the anti-PERK antibody by IF (× 63 magnification). (B) From the same treatment, cells were lyzed and the cell extracts were subsequently analyzed by Western blot for the expression of P-ERK, ERK, P-PXN and PXN. (C) The cells treated in A were fixed and immunostained to study the localization of P-PXN. (D) HBCc-12A cells were treated with E2 for longer time to study cyclin D1 expression. The extracts were analyzed by Western blot for the expression of cyclin D1 and tubulin. (E) To study the role of ERK phosphorylation on cyclin D1 expression, HBCc-12A cells were treated or not with the MEK inhibitor, U1026 (10 μM) for 15 min prior to E2 treatment. Expression of P-ERK, ERK, P-PXN, PXN, cyclin D1 and tubulin were assessed by Western blot. (F) Next, we investigated the role of ERα-36 on ERK signaling. To this aim, HBCc-12A cells were transfected with pSG5-Flag vector, pSG5-Flag-ERα-36-CTD or pSG5-Flag- ERα-36-CTD-L297A for 36 h. The cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot for P-ERK, ERK, P-PXN, PXN and cyclin D1 expression (G–J) HBCx-12A PDX from which HBCc-12A cells were derived was grown with and without the supplementation of E2 in the drinking water of mice (see Supplementary Appendix Figure S2i). Mice were killed at the end of the experiment (day 51) and tumours were embedded in paraffin. (G) A bright field PLA was performed to study ERα-36/Src interactions in each group. The brown dots represent protein-protein interactions (× 40 magnification). (H) The interactions were quantified as described in Figure 2B. The P-value was determined using the Student's test. ***P<0.001. (I) On the same embedded tumors, P-ERK was also assessed by IHC staining. (J) P-PXN was assessed by IHC staining.

Next, we investigated whether the pathway occurred in the original PDX from which the HBCc-12A were derived (HBCx-12A) grown in the presence of E2. We found an increase in ERα-36/Src interaction (Figures 6G and H), P-ERK (Figure 6I) and P-PXN (Figure 6J). Unfortunately, we were unable to detect ERα-36/ERK2 interaction possibly due to the fact that ERK2 antibodies may not work in PLA conducted on formalin-fixed tissues. In addition, this pathway was investigated in the ERα-negative HBL100 cell line, and we observed that E2 triggered ERα-36/ERK2 interaction, ERK activation, PXN phosphorylation, as well as cell proliferation (Supplementary Figures S6a–d).

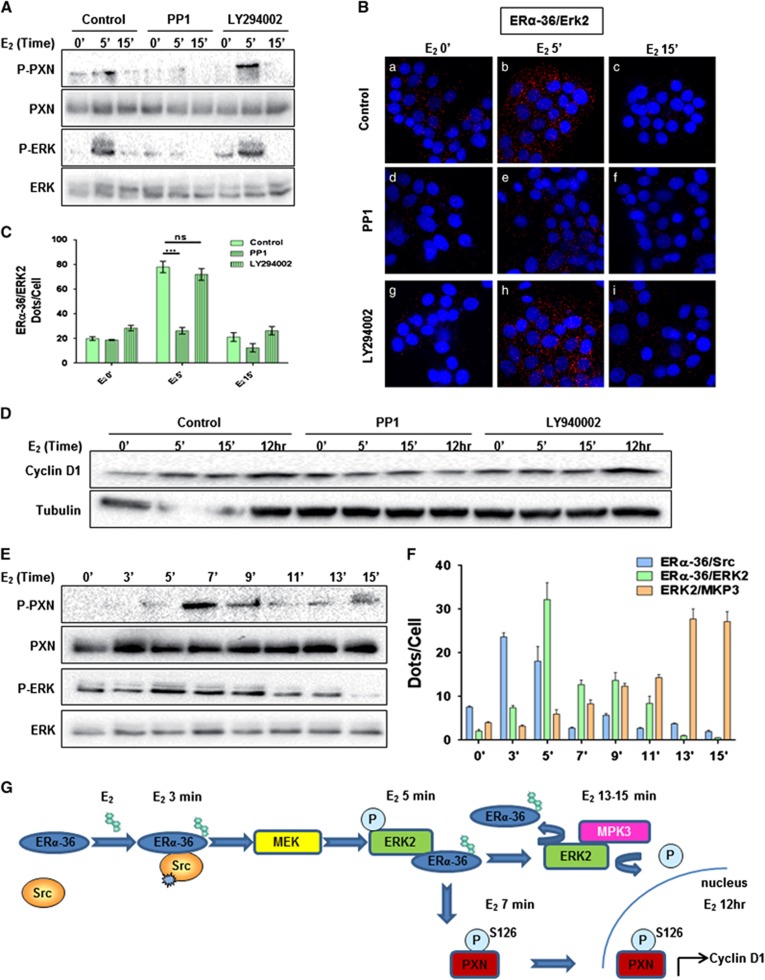

We then wondered whether Src and PI3K activities occured upstream of the ERK pathway, and found that only PP1 treatment completely abolished E2-induced ERK and PXN phosphorylation (Figure 7A), ERα-36/ERK2 interaction (Figures 7B and C, compare panels d–f to control experiments panels a–c), as well as cyclin D1 expression (Figure 7D). LY294002 had no effect on these activities (Figures 7A and B(g–i) 7C and 7D). Finally, the kinetic of the various events of this signaling pathway was determined by treating HBCc-12A cells with E2 for a very short period of time. We unveiled that (i) ERα-36 associates with Src within 3 min of E2 treatment then dissociates after 5 min (Figure 7F and Supplementary Figure S7), (ii) ERα-36 binds to ERK2 with a peak occurring after 5 min of treatment, concomitantly with ERK and PXN phosphorylation (Figure 7E), and (iii) after 11 min, MKP3 starts binding to ERK2 and the interaction until 15 min (Figure 7F and Supplementary Figure S7).

Figure 7.

Src activity regulates E2-induced ERK signaling. (A–D) To study the role of Src and PI3K on E2-induced ERK signaling, HBCc-12A cells were treated or not with PP1 (5 μM) or LY294002 (20 μM) for 15 min before E2 treatment. (A) Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot for the expression of P-ERK, ERK, P-PXN and PXN. (B) Cells were also used to perform PLA to detect ERα-36/ERK2 interactions (× 63 magnification). (C) Quantification of the interactions was performed as in Figure 2B. The experiment was performed in triplicate, and this graph is representative of one of the experiments. P-value was determined by the Student's test. ***P<0.001. (D) HBCc-12A cells were treated as described in (A) but for a longer period to study cyclin D1 expression. (E and F) HBCc-12A cells were treated with E2, cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot for the expression of P-ERK, ERK, P-PXN and PXN. (F) ERα-36/Src, ERα-36/ERK2 and ERK2/MKP3 interactions were studied by PLA (Supplementary Figure S7), the quantifications were performed as described in Figures 2B. (G) E2/ERα-36 signaling pathway.

Discussion

Approximatively 80% of breast cancers express ERα and endocrine therapies have led to significant improvements in patient survival. In contrast, triple-negative breast cancers, which are negative for ERα, for the progesterone receptor and for the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, are highly aggressive and treatment options are, so far, restricted to cytotoxic agents.30 In this study, focusing on triple negative breast cancers, we unveiled the precise molecular events underlying ERα-36-mediated signaling pathway. These findings introduce a new paradigm in which ERα-36 activates ERK signaling at two levels, at the plasma membrane by binding to Src and in the cytoplasm by directly binding to P-ERK.

Similarly to ERα, we observed the binding of ERα-36 with Src and PI3K; however, the mechanisms underlying the formation of the complex seem different. Indeed, the ERα/Src interaction was dependent on the methylation of ERα on residue R260 (corresponding to R184 in ERα-36),10 as well as on its phosphorylation on the Y537 residue, a docking site for the SH2 domain of Src.31 Here, we were unable to detect any ERα-36 methylation on R184, and, in addition Y537 was not present in ERα-36. We can speculate that a yet unidentified tyrosine residue could be involved in their interaction.

The functional activation of ERK by ERα-36 was shown by various groups.12,17,24 In the present study, we mechanistically demonstrated that two routes tightly regulate ERK2 activation by acting both on its phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. We described for the first time a direct binding of ERα-36 with ERK2 via a newly identified D domain located in its CTD. The D domain is a conserved docking motif in MAPKs used in the recognition of their activators, substrates and regulators, such as kinases and phosphatases.32 A combined in silico 3D model and in vitro approach enabled us to identify the crucial role of L297 in the binding interaction between ERα-36 and ERK2, which was confirmed since its point mutation completely disrupted the interaction with ERK2 (Figure 3B). Deactivation of ERK1/2 is carried out by several serine threonine or tyrosine phosphatases, including MKP3, a dual phosphatase with the capacity to dephosphorylate both threonine and tyrosine residues.33,34 Interestingly, we found that ERα-36 was capable of preventing binding of MKP3 to ERK presumably through stearic competition, maintaining the activation of ERK. This was confirmed by disrupting the ERα-36/ERK2 interaction, allowing a more rapid binding of MPK3, and resulting in the constant dephosphorylation of ERK. Such a regulation of P-ERK has already been described for the adaptor molecule MyD88 and the Rab2A GTPase. Indeed, MyD88 and Rab2A GTPase prevent ERK inactivation by MKP3, leading to cell transformation35 and to promoting breast cancer stem cells, respectively.36

Although many substrates for ERK are localized in the nucleus, others are found in the cytosol.37 PXN is a 68-kDa focal adhesion-associated protein, which functions as a scaffolding protein assembling signaling molecules into complex downstream of integrin and growth factors, regulating matrix organization, cell motility and proliferation.38,39 Initially, ERK was identified as a priming kinase for the GSK3-mediated PXN phosphorylation on residue S126.28 Furthermore, PXN was shown to function as an upstream mediator of ERK activation and a downstream regulator of ERK signaling via different phosphorylations. The epidermal growth factor and dihydrotestosterone (a ligand to Androgen receptor) induce Src-mediated phosphorylation of PXN on residue Y118 to activate ERK phosphorylation but also trigger ERK-mediated phosphorylation of PXN on residue S126.40 Since we demonstrated that P-PXN translocates to the nucleus following E2 treatment (Figure 6C), and that ERα-36 triggers cyclin D1 transcription,20 we speculated that PXN activates cyclin D1, thus triggering cell proliferation (Figure 6D).

Based on our results, we propose the following model of regulation of the E2/ERα-36 signaling pathway (Figure 7G). When E2 enters within the cells, it causes the interaction of ERα-36 with Src, inducing MEK activation, which in turn phosphorylates ERK. Activated ERK phosphorylates its substrate PXN on S126, triggering its translocation to the nucleus where it acts as a coactivator to induce cyclin D1 transcription, and increasing cell proliferation. Interestingly, ERα-36 reinforces the signal induced by the P-ERK phosphorylation by preventing its rapid dephosphorylation by MKP3.

The identification of this new signaling pathway could have significant implications in breast cancer treatment. Indeed, a retrospective study of 896 cases of breast cancer patients revealed that 40% cases of ERα-positive breast cancers expressed ERα-36, and those patients were less inclined to benefit from tamoxifen therapy.16 Moreover, 40% of ERα-negative breast cancers, while lacking ERα expression, expressed ERα-36. Its prognostic value in this breast cancer subtype is less clear (for a review see Gu et al.14). Future studies could determine whether this novel pathway is conserved in ERα-positive and -negative subtypes and for ERα-36-positive tumors, while combining Src or MEK inhibitors with hormonotherapy may improve the response to conventional treatments.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

A polyclonal antibody against ERα-36 specifically generated for this study by Covalab (Lyon, France), and commercially-available antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Cell culture

MCF-7 and HeLa cells were obtained from ATCC. The HBCc-12A cell line was established from the HBCx-12A xenograft, a PDX model of primary triple-negative breast cancer.23 Additional information can be found in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Plasmids and mutagenesis

The pCDNA3-ERα-36 plasmid was a gift from Dr Wang.4 The mutations were obtained using the Quickchange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Additional information can be found in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Proximity ligation assay (PLA)

This technology developed by Olink Bioscience (Sweden) enables the visualization of protein/protein interactions in situ and was firstly published in 2006.26 Additional information can be found in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Molecular modeling

Homology models of ERα-36 LBD (118-310) were obtained using the structure prediction server ROBETTA (http://robetta.bakerlab.org/). The amino-acid sequence of ERα-36 was retrieved from NCBI (GenBank: BX640939.1). 3D Models were compared to the crystal structures of ERα-E2 (PDB ID: 1A52). Analysis of the complexes between ERK2 and D motif peptides was performed as described in the Supplementary Materials and Methods. Figures were realized with the PyMOL molecular graphics software.

Acknowledgments

We thank F Nasri, C. Languilaire, A. Colombe, L Odeyer and F Assayag for technical support, Y Mikaelian (CRCL, Lyon) for the Histone-GFP vector, G Castoria for the PI3K plasmid, Dr Wang for the pCDNA3-ERα-36 plasmid, P Chambon for the HEGO plasmid, F Lenfant for the ERα-46 plasmid, B. Manship for the proofreading of the manuscript. Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (comité de Saône-et-Loire), ‘Fondation Arc Cancer', Canceropole CLARA, INCA and DGOS. ‘région Rhône-Alpes' and ‘ Ligue Contre le Cancer' for SO, French Ministry of Research, ‘Fondation Arc Cancer' and NIH for CP. ‘Fondation Arc Cancer' for JJ, NR, YC and AD: grant ANR-10-LABX-0030-INRT.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Nilsson S, Makela S, Treuter E, Tujague M, Thomsen J, Andersson G et al. Mechanisms of estrogen action. Physiol Rev 2001; 81: 1535–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong EH, Pike AC, Hubbard RE. Structure and mechanism of the oestrogen receptor. Biochem Soc Trans 2003; 31(Pt 1): 56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Romancer M, Poulard C, Cohen P, Sentis S, Renoir JM, Corbo L. Cracking the estrogen receptor's posttranslational code in breast tumors. Endocr Rev 2011; 32: 597–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zhang X, Shen P, Loggie BW, Chang Y, Deuel TF. Identification, cloning, and expression of human estrogen receptor-alpha36, a novel variant of human estrogen receptor-alpha66. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 336: 1023–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao J, Jiang X, Wang Y, Chen B. Advances in the understanding of the structure and function of ER-alpha36,a novel variant of human estrogen receptor-alpha. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2011; 127: 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER. Membrane oestrogen receptor alpha signalling to cell functions. J Physiol 2009; 587(Pt 21): 5019–5023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER. Extranuclear steroid receptors are essential for steroid hormone actions. Annu Rev Med 2015; 66: 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castoria G, Migliaccio A, Bilancio A, Di DM, de FA, Lombardi M et al. PI3-kinase in concert with Src promotes the S-phase entry of oestradiol-stimulated MCF-7 cells. EMBO J 2001; 20: 6050–6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song RX, Zhang Z, Santen RJ. Estrogen rapid action via protein complex formation involving ERalpha and Src. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2005; 16: 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Romancer M, Treilleux I, Leconte N, Robin-Lespinasse Y, Sentis S, Bouchekioua-Bouzaghou K et al. Regulation of estrogen rapid signaling through arginine methylation by PRMT1. Mol Cell 2008; 31: 212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulard C, Treilleux I, Lavergne E, Bouchekioua-Bouzaghou K, Goddard-Leon S, Chabaud S et al. Activation of rapid oestrogen signalling in aggressive human breast cancers. EMBO Mol Med 2012; 4: 1200–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong JS, Zhang QH, Wang ZB, Li S, Yang CR, Fu XQ et al. ER-alpha36, a novel variant of ER-alpha, mediates estrogen-stimulated proliferation of endometrial carcinoma cells via the PKCdelta/ERK pathway. PLoS One 2010; 5: e15408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri RA, Olivares-Navarrete R, Cuenca N, Hadadi A, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z. Membrane estrogen signaling enhances tumorigenesis and metastatic potential of breast cancer cells via estrogen receptor-alpha36 (ERalpha36). J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 7169–7181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Chen T, Lopez E, Wu W, Wang X, Cao J et al. The therapeutic target of estrogen receptor-alpha36 in estrogen-dependent tumors. J Transl Med 2014; 12: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LM, Cao J, Deng H, Chen P, Gatalica Z, Wang ZY. ER-alpha36, a novel variant of ER-alpha, is expressed in ER-positive and -negative human breast carcinomas. Anticancer Res 2008; 28: 479–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Dong B, Li Z, Lu Y, Ouyang T, Li J et al. Expression of ER-{alpha}36, a novel variant of estrogen receptor {alpha}, and resistance to tamoxifen treatment in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 3423–3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zhang X, Shen P, Loggie BW, Chang Y, Deuel TF. A variant of estrogen receptor-{alpha}, hER-{alpha}36: transduction of estrogen- and antiestrogen-dependent membrane-initiated mitogenic signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 9063–9068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Ding L, Kang L, Wang ZY. Estrogen receptor-alpha 36 mediates mitogenic antiestrogen signaling in ER-negative breast cancer cells. PLoS One 2012; 7: e30174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Zhang XT, Bian XW, Guo YM, Wang ZY. Disruption of the ER-alpha36-EGFR/HER2 positive regulatory loops restores tamoxifen sensitivity in tamoxifen resistance breast cancer cells. PLoS One 2014; 9: e107369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XT, Kang LG, Ding L, Vranic S, Gatalica Z, Wang ZY. A positive feedback loop of ER-alpha36/EGFR promotes malignant growth of ER-negative breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2011; 30: 770–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Li G, Li Z, Yu X, Zheng Y, Jin K et al. Estrogen-independent effects of ER-alpha36 in ER-negative breast cancer. Steroids 2012; 77: 666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L, Zhang X, Xie Y, Tu Y, Wang D, Liu Z et al. Involvement of estrogen receptor variant ER-alpha36, not GPR30, in nongenomic estrogen signaling. Mol Endocrinol 2010; 24: 709–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marangoni E, Vincent-Salomon A, Auger N, Degeorges A, Assayag F, de CP et al. A new model of patient tumor-derived breast cancer xenografts for preclinical assays. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 3989–3998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Yin L. Estrogen receptor alpha-36 (ER-alpha36): a new player in human breast cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2015; 418: 193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabodi S, Moro L, Baj G, Smeriglio M, Di SP, Gippone S et al. p130Cas interacts with estrogen receptor alpha and modulates non-genomic estrogen signaling in breast cancer cells. J Cell Sci 2004; 117(Pt 8): 1603–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderberg O, Gullberg M, Jarvius M, Ridderstrale K, Leuchowius KJ, Jarvius J et al. Direct observation of individual endogenous protein complexes in situ by proximity ligation. Nat Methods 2006; 3: 995–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R Jr.. ERK1/2 MAP kinases: structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol Res 2012; 66: 105–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Li M, Vrana J, Schaller MD. Glycogen synthase kinase 3- and extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent phosphorylation of paxillin regulates cytoskeletal rearrangement. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26: 2857–2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A, De CI, Defranco DB, Deng FM, Melamed J, Kapur P et al. Paxillin mediates extranuclear and intranuclear signaling in prostate cancer proliferation. J Clin Invest 2012; 122: 2469–2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1938–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varricchio L, Migliaccio A, Castoria G, Yamaguchi H, de FA, Di DM et al. Inhibition of estradiol receptor/Src association and cell growth by an estradiol receptor alpha tyrosine-phosphorylated peptide. Mol Cancer Res 2007; 5: 1213–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanoue T, Adachi M, Moriguchi T, Nishida E. A conserved docking motif in MAP kinases common to substrates, activators and regulators. Nat Cell Biol 2000; 2: 110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muda M, Boschert U, Dickinson R, Martinou JC, Martinou I, Camps M et al. MKP-3, a novel cytosolic protein-tyrosine phosphatase that exemplifies a new class of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase. J Biol Chem 1996; 271: 4319–4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muda M, Theodosiou A, Gillieron C, Smith A, Chabert C, Camps M et al. The mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-3N-terminal noncatalytic region is responsible for tight substrate binding and enzymatic specificity. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 9323–9329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coste I, Le CK, Kfoury A, Hmitou I, Druillennec S, Hainaut P et al. Dual function of MyD88 in RAS signaling and inflammation, leading to mouse and human cell transformation. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 3663–3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ML, Gong C, Chen CH, Hu H, Huang P, Zheng M et al. The Rab2A GTPase promotes breast cancer stem cells and tumorigenesis via Erk signaling activation. Cell Rep 2015; 11: 111–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S, Seger R. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase: multiple substrates regulate diverse cellular functions. Growth Factors 2006; 24: 21–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MC, Turner CE. Paxillin: adapting to change. Physiol Rev 2004; 84: 1315–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller MD. Paxillin: a focal adhesion-associated adaptor protein. Oncogene 2001; 20: 6459–6472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A, O'Malley K, Wang Z, Raj GV, Defranco DB, Hammes SR. Paxillin regulates androgen- and epidermal growth factor-induced MAPK signaling and cell proliferation in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 28787–28795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanenbaum DM, Wang Y, Williams SP, Sigler PB. Crystallographic comparison of the estrogen and progesterone receptor's ligand binding domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 5998–6003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MC, Allan LA, Mancini EJ, Clarke PR. The docking interaction of caspase-9 with ERK2 provides a mechanism for the selective inhibitory phosphorylation of caspase-9 at threonine 125. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 3854–3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.