Significance

Changing interactions between climate and fire are impacting biodiversity. We examined the longest vegetation survey record in the Fynbos, South Africa, a fire-prone Mediterranean-type ecosystem and Global Biodiversity Hotspot, finding significant impacts of prolonged hot and dry postfire weather and invasive plants on species diversity. Graminoids, herbs, and species that sprout after fire declined in diversity, whereas the climatic niches of species unique to each survey showed a 0.5 °C increase in maximum temperature. The consequences of these changes for the structure and function of this ecosystem are largely unknown. This interaction between fire and changing climate is cause for concern in fire-prone ecosystems subject to severe summer droughts and temperature extremes, such as southern Australia, California, and South Africa.

Keywords: Cape Floristic Region, Fynbos, South Africa, biodiversity, climate change

Abstract

Prolonged periods of extreme heat or drought in the first year after fire affect the resilience and diversity of fire-dependent ecosystems by inhibiting seed germination or increasing mortality of seedlings and resprouting individuals. This interaction between weather and fire is of growing concern as climate changes, particularly in systems subject to stand-replacing crown fires, such as most Mediterranean-type ecosystems. We examined the longest running set of permanent vegetation plots in the Fynbos of South Africa (44 y), finding a significant decline in the diversity of plots driven by increasingly severe postfire summer weather events (number of consecutive days with high temperatures and no rain) and legacy effects of historical woody alien plant densities 30 y after clearing. Species that resprout after fire and/or have graminoid or herb growth forms were particularly affected by postfire weather, whereas all species were sensitive to invasive plants. Observed differences in the response of functional types to extreme postfire weather could drive major shifts in ecosystem structure and function such as altered fire behavior, hydrology, and carbon storage. An estimated 0.5 °C increase in maximum temperature tolerance of the species sets unique to each survey further suggests selection for species adapted to hotter conditions. Taken together, our results show climate change impacts on biodiversity in the hyperdiverse Cape Floristic Region and demonstrate an important interaction between extreme weather and disturbance by fire that may make flammable ecosystems particularly sensitive to climate change.

Amid mounting evidence of climate change impacts on living systems (1–3), there is increasing concern about changing disturbance–climate interactions and their potential impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem function (4–9). Fire is a ubiquitous driver of disturbance across the globe and is essential for the healthy functioning and maintenance of many ecosystems (10, 11), but changes in fire regime or postfire weather may drive major shifts in the composition, structure, and function of ecosystems (12). Changes in climate and weather can alter fire regimes (7, 8), whereas increasingly extreme or prolonged periods of heat or drought in the years immediately after fire may affect ecosystem resilience and diversity by inhibiting seed germination or increasing mortality of seedlings or sprouting individuals (13–15). Where these impacts alter the functional composition of communities, this change can drive major changes in ecosystem structure and function (16–18). Although interactions between climate change and fire are likely to affect ecosystems across the globe, they are of particular concern in fire-dependent ecosystems subject to stand-replacing crown fires, where community composition is essentially reset by fire. This includes multiple global biodiversity hotspots of conservation concern, such as the Fynbos of the Cape Floristic Region (CFR) of South Africa and other Mediterranean-type ecosystems (19).

Fire has been a strong driver of diversification and the evolution of plant life-history strategies in the Fynbos (10, 20, 21) and is a necessary natural disturbance for the maintenance of biodiversity (10, 17, 21). Fynbos plant species use strategies to persist or regenerate after fire, and most depend on fire to complete their life cycle. Many resprout from storage organs or retain seeds in fireproof (serotinous) cones that open after fire, whereas others use dispersal vectors such as ants or rodents to facilitate underground storage of seed, later triggered to germinate by heat or smoke (20). Postfire weather conditions and the frequency, season, and intensity of fires are important determinants of vegetation structure and composition (21, 22), and there is increasing concern that these properties of the disturbance regime are changing, resulting in altered ecosystems and biodiversity loss (7, 21, 23).

Observational studies report high seedling mortality in the first summer after fire (10, 24), and several experimental studies working on Fynbos species have found that temperatures 1.4–3.5 °C above ambient, or drought treatments over a period of 6–75 d, drastically reduce germination and seedling survival rates (14, 15). Weather records for the CFR report increases in minimum and maximum temperatures, lower summer rainfall, fewer rain days, and decreases in wind run and minimum relative humidity over the past 30–50 y (4, 25–27). Thus, plants are encountering higher temperatures and longer hot and dry spells during summer, which we expect to result in lower germination rates and higher mortality of seedlings or sprouting individuals in the first summer after fire. Although reduced wind run (lower wind speeds and greater numbers of still days) may reduce potential evapotranspiration and drought stress, it also reduces sensible heat loss, increasing the potential for heat stress (25).

Little is known about the degree to which different growth forms or life history types in the CFR vary in response to postfire weather extremes. Existing studies are limited to germination and seedling survival trials on shrubs in the family Proteaceae (14, 15, 28). Shrubs are perhaps the least likely to be affected by climate extremes because they are deeper-rooted than other Fynbos growth forms, with roots reaching depths of 17 cm within 16 wk of germination (29). Shallow-rooted perennial species, including most graminoids and herbs in Fynbos, are likely to be most sensitive, as reported in other ecosystems (30). A recent global review proposes that species that resprout are more resilient to drought stress, but reports that empirical studies are few and conflicting (31). Fynbos studies report a higher proportion of resprouters in sites with wetter soils at the scale of both local communities and across biogeographic regions (18, 32, 33), invoking higher moisture requirements for establishment and regeneration, owing to the need to allocate resources to burls or lignotubers. This pattern suggests that resprouter species may be highly sensitive to extreme weather in the first year after fire.

Recently, there has been increasing emphasis on testing alternative or compounding nonclimatic drivers of change to strengthen confidence in climate change impact science (34). Two potential drivers in Fynbos ecosystems are the impact of alien plant invasions—which are considered the greatest threat to plant species in South Africa after habitat loss (35) —and the effect of changes in indigenous overstorey shrub density on understorey species diversity (36). The presence and density of serotinous overstorey shrub species at a site vary greatly between fires (37), and higher densities alter the composition and diversity of understorey species (36). Alien trees and shrubs from the genera Acacia and Pinus (38) are particularly problematic in Fynbos ecosystems, impacting diversity and ecosystem function by suppressing native vegetation, increasing biomass loads (and thus the intensity of fires), reducing soil moisture, and changing soil nutrient fluxes (16, 39–41). These species were introduced to our site >150 y ago to stabilize sand dunes and supplement the meager firewood provided by indigenous shrubs, but rapidly became invasive (42, 43). Intensive clearing operations were started in the 1970s, and woody alien species were almost completely eradicated by the late 1980s (39), but we would anticipate a legacy of invasion history on diversity at our site (41, 44).

We examined the longest-running set of permanent vegetation plots in the Fynbos of South Africa (44 y) to test for negative impacts of increasingly prolonged periods of hot and dry weather in the first summer after fire on plant diversity. Plots were established in the Cape of Good Hope section of Table Mountain National Park—perhaps the most diverse portion of the Fynbos (45)—in 1966 (46) and reenumerated in 1996 (37) and 2010 (this study). To strengthen confidence in our findings, we tested for the influence of multiple potential drivers of change (34), including fire history, historical woody alien plant densities, and impacts of changes in overstorey shrub density on understorey diversity. We also hypothesized that responses to postfire weather extremes would vary among species with different life histories, with shallow-rooted growth forms worst affected, and species that resprout after fire being as sensitive, if not more, than species that recruit from seed.

To test our hypotheses, we first analyzed the weather record for the reserve from 1963 to 2009, looking for evidence of directional change in the intensity of extreme weather events. Second, we tested for significant change in species richness within plots through time. Third, we modeled the change in plot species richness between surveys as a function of among-site differences in the severity of extreme weather events [number of consecutive hot and dry days (CHDs)] experienced in the first summer after fire, historical alien species densities, changes in the presence of serotinous overstorey species, and postfire vegetation age. Note that the postfire weather experienced varies greatly between plots, because they burned at different times. These analyses were repeated for all species and separately for each fire response type (seeder vs. resprouter) and growth form to test for differences among functional groups in response to change drivers. Finally, we tested for an imprint of climate-driven shifts in species composition across all plots by comparing the mean maximum temperature tolerance of the species that showed turnover at the study level (i.e., the species unique to each survey), which we derived from their geographic distribution records across the CFR.

Results

Weather Record.

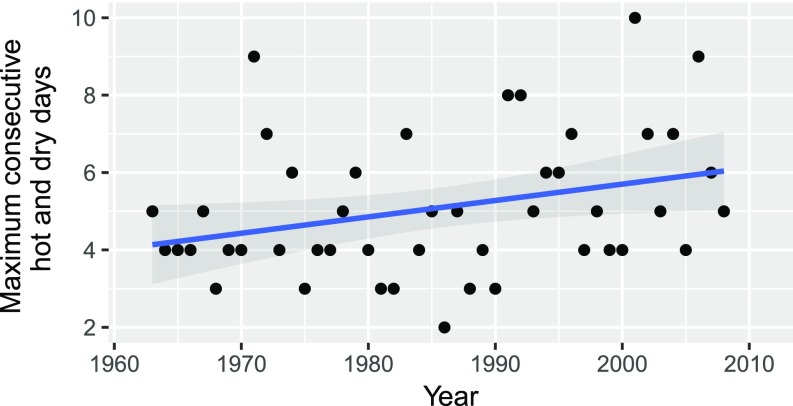

Previous analysis of the 48-y weather record for the site revealed a 1.2 °C increase in monthly mean maximum temperatures, a 1 °C increase in monthly mean minimum temperatures, and a 2-mm increase in cumulative monthly rainfall (27). Although their analysis found no significant change in the annual maximum number of consecutive dry days (ranging from 21 to 91 d), we found a significant increase in the annual maximum CHD from 4 to 6 [Fig. 1; posterior mean of the slope = 0.043; 95% confidence interval = 0.007–0.085; probability of overlapping zero (pMCMC; ref. 47) < 0.05].

Fig. 1.

The maximum CHD at the Cape Point Global Atmospheric Watch Station for the Austral summer for the years 1963–2009. These were days where the temperature exceeded the 0.9 quantile of the record (21 °C) and rainfall was <1 mm.

Changes in Species Numbers Through Time.

Total numbers of perennially apparent species across the fifty-four 50- plots declined from 298 in 1966 to 283 in 1996 and 261 in 2010, representing 381 species across all surveys and 41, 29, and 37 species unique to each successive survey. Turnover among sites remained similarly high for each survey, with median Sørenson’s dissimilarity = 0.71 (interquartile range 0.59–0.83), 0.70 (0.57–0.83), and 0.72 (0.6–0.85) for 1966, 1996, and 2010 respectively. This result suggests that the decline in species numbers across the reserve was not due to homogenization of composition across plots.

Generalized linear mixed effects models (47) revealed significant declines in plot-level total species richness with each survey, even after differences in vegetation age (time since fire) were accounted for (Table 1). Seeder species richness declined significantly over the period 1966–1996, but did not differ significantly between 1966 and 2010, suggesting some degree of recovery between the second and third surveys, following the earlier removal of woody alien plants. Resprouter species declined significantly with each survey. Splitting species by growth form revealed declining graminoid and herb species richness with each survey and no change in tall shrubs or geophytes. Low shrubs declined initially and then recovered by 2010, similar to the set of all seeder species. The diversity of all life forms declined with increasing time since fire, because fewer individuals were sampled within the fixed plot area as plants increased in size and stands thinned due to competition (48).

Table 1.

Results of generalized linear mixed-effects models exploring change in numbers of species within plots between surveys, while accounting for differences in vegetation age

| Set | Intercept | Age | 1996 | 2010 |

| All species | 3.859*** | −0.022*** | −0.087** | −0.091* |

| Resprouters | 3.078*** | −0.016*** | −0.088† | −0.226*** |

| Seeders | 3.259*** | −0.027*** | −0.095* | 0.007NS |

| Tall shrubs | 1.63*** | −0.011* | 0.055NS | −0.006NS |

| Low shrubs | 3.05*** | −0.032*** | −0.095* | 0.027NS |

| Herbs | 0.634*** | −0.028* | −0.207NS | −0.507*** |

| Graminoids | 2.749*** | −0.014*** | −0.106* | −0.251*** |

| Geophytes | 0.921*** | −0.015* | −0.098NS | −0.111NS |

Values indicate posterior means of the coefficients. NS, pMCMC > 0.05; †pMCMC < 0.1; *pMCMC < 0.05; **pMCMC < 0.01; ***pMCMC < 0.005.

The Drivers of Species Loss.

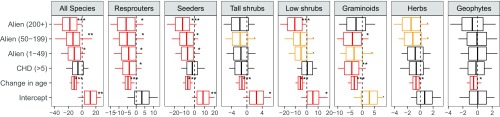

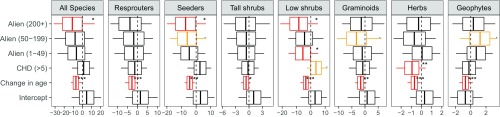

Estimates for the effects of high CHDs in the first summer after fire on the change in species richness were negative for most groups, but near zero for seeders, low shrubs, and geophytes over the period 1966–2010 (Fig. 2). These effects were significant for graminoid (posterior mean: −4.260; pMCMC < 0.01) and all resprouter species (posterior mean: −3.998; pMCMC < 0.05). Herb species showed a significant decline over the initial (posterior mean: −0.930; pMCMC < 0.05; Fig. S1), but although a decline was still evident over the entire study period, it was not significant (posterior mean: −0.627; 95% confidence interval: −1.704 to 0.496; pMCMC = 0.26). Low shrubs showed no response over the entire period, but a weakly significant positive response to higher CHDs between 1966 and 1996, possibly due to reduced competition from herbs and graminoids.

Fig. 2.

Estimates of the regression coefficients from generalized linear models exploring the drivers of change in perennial species numbers within plots for the full study period, 1966–2010. Each image represents a separate model. Models were run on all species combined and separately for each fire response strategy (seeders vs. resprouters) and five major growth forms [tall shrubs (>1 m), low shrubs (<1 m), graminoids, herbs, and geophytes]. Vertical bars represent the means, boxes the 95% credible intervals, and whiskers the maximum and minimum values of the posterior distributions. .pMCMC < 0.1; *pMCMC < 0.05; **pMCMC < 0.01; ***pMCMC < 0.005. Red and yellow boxes indicate pMCMC values of <0.05 and <0.1, respectively. Change in age is the difference in time since fire between surveys. CHD is a factor with two levels for plots whose longest period of consecutive hot and dry days [maximum temperature > 0.9 quantile (21 °C) and rainfall < 1 mm] experienced in the first summer after fire was less or greater than 5 d; alien is a factor representing the maximum historical density of alien plants split into four levels: 0; 1–49; 50–199; and 200+.

Fig. S1.

Estimates of the regression coefficients from generalized linear models exploring the drivers of change in perennial species numbers within plots for the full study period, 1966–1996. Each image represents a separate model. Models were run on all species combined and separately for each fire response strategy (seeders vs. resprouters) and five major growth forms [tall shrubs (>1 m), low shrubs (<1 m), graminoids, herbs, and geophytes]. Vertical bars represent the means, boxes the 95% credible intervals, and whiskers the maximum and minimum values of the posterior distributions. .pMCMC < 0.1; *pMCMC < 0.05; **pMCMC < 0.01; ***pMCMC < 0.005. Red and yellow boxes indicate pMCMC values of <0.05 and <0.1, respectively. Change in age is the difference in time since fire between surveys. CHD is a factor with two levels for plots whose longest period of CHDs [maximum temperature > 0.9 quantile (21 °C) and rainfall < 1 mm] experienced in the first summer after fire were less or greater than 5 d; alien is a factor representing the maximum historical density of alien plants split into four levels: 0; 1–49; 50–199; and 200+.

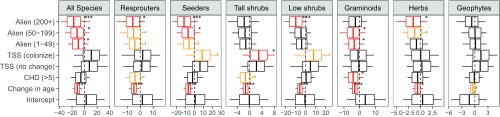

All species sets other than geophytes responded negatively to alien infestation, with increasing impacts of higher densities. These effects were less evident over the initial 1966–1996 period and less significant for tall shrubs and herbs. Serotinous tall shrubs occurred in 34, 36, and 45 plots across the three successive surveys, but their presence had only weak positive effects on tall shrub and seeder species richness, with which they are autocorrelated, and low shrubs, which are likely to respond to environmental conditions in similar ways (Fig. S2).

Fig. S2.

Estimates of the regression coefficients from generalized linear models exploring the drivers of change in perennial species numbers within plots for the full study period, 1966–2010, including a three-level factor (TSS) representing the loss (−1, the intercept), stability (0), or gain (+1) of tall serotinous shrub species. Each image represents a separate model. Models were run on all species combined and separately for each fire response strategy (seeders vs. resprouters) and five major growth forms [tall shrubs (>1 m), low shrubs (<1 m), graminoids, herbs, and geophytes]. Vertical bars represent the means, boxes the 95% credible intervals, and whiskers the maximum and minimum values of the posterior distributions. .pMCMC < 0.1; *pMCMC < 0.05; **pMCMC < 0.01; ***pMCMC < 0.005. Red and yellow boxes indicate pMCMC values <0.05 and <0.1, respectively. Change in age is the difference in time since fire between surveys. CHD is a factor with two levels for plots whose longest period of CHDs [maximum temperature > 0.9 quantile (21 °C) and rainfall < 1 mm] experienced in the first summer after fire was less or greater than 5 d; alien is a factor representing the maximum historical density of alien plants split into four levels: 0; 1–49; 50–199; and 200+.

Climate-Driven Shifts in Species Composition.

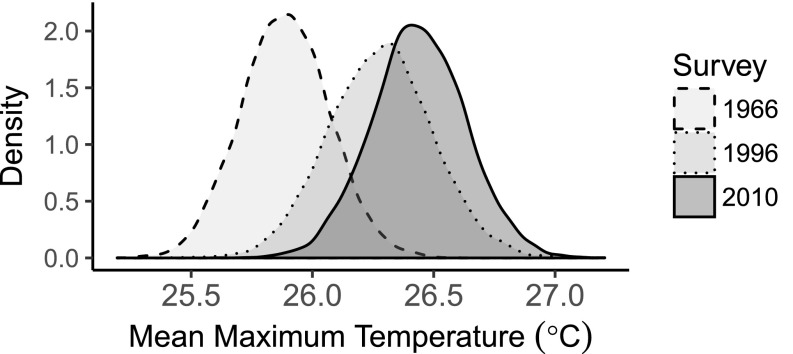

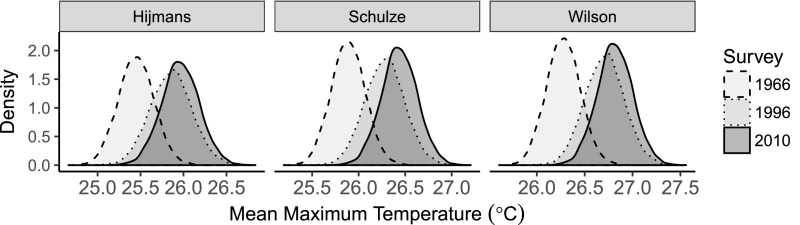

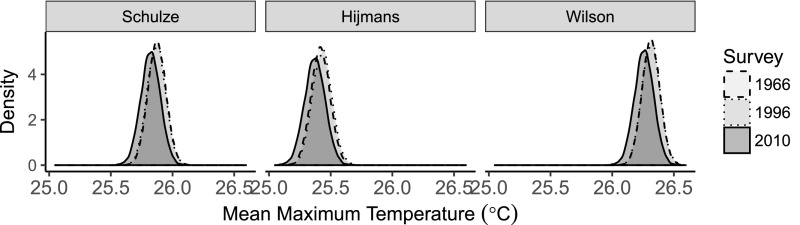

We compared the mean maximum temperature tolerance of the sets of species unique to each survey based on their macroclimatic tolerances. Species-level and then combined mean macroclimatic tolerances for each species set were estimated from climate data extracted for species distribution records from gridded climatologies (49–51). They revealed significant shifts toward hotter mean maximum temperature tolerance (Fig. 3), suggesting that species lost from the plots tended to be from cooler regions, whereas those that colonized plots could tolerate the higher temperatures now observed at our site. These results were consistent for all three climatologies available for our study region (Fig. S3) (49–51).

Fig. 3.

Posterior distributions of the mean maximum temperature tolerance for the sets of species unique to each survey, based on estimates of each species’ tolerance from geographic distribution records and gridded climatologies for the CFR. There were 41 species in 1966 (posterior mean: 25.89 °C; 95% highest-density interval: 25.54–26.25), 29 species in 1996 (posterior mean: 26.28 °C; 95% highest-density interval: 25.15–25.73), and 37 species in 2010 (posterior mean: 26.44 °C; 95% highest density interval: 25.92–26.95).

Fig. S3.

Posterior distributions of the mean maximum temperature tolerance for the sets of species unique to each survey, based on estimates of each species’ tolerance from geographic distribution records and three gridded climatologies for the CFR (49–51).

The magnitude of the observed shift in mean maximum temperature tolerance (0.55 °C) was less than the temperature change observed at the site over the full study period (1.2 °C). We would expect this result, if climate impacts are only realized when sites are exposed to extreme postfire weather, given that many plots last burnt in the 1980s and some more recent fires were followed by benign summers. Similarly, we would not expect comparison of all species occurring in each survey to reveal significant shifts (Fig. S4), because many species may not have encountered extreme postfire weather or have been buffered by climatic variation among plots within the study area (72% of species were stable at the study level), overwhelming any signal.

Fig. S4.

Posterior distributions of the mean maximum temperature tolerance for the sets of all species from each survey, based on estimates of each species’ tolerance from geographic distribution records and gridded climatologies for the CFR (49–51).

Discussion

Species diversity declined in our study site through time, varying between plots in response to spatial differences in the intensity of extreme weather experienced in the first summer after fire and historical woody alien plant invasion. Our dataset allowed us to test the impact of the range of most likely drivers of species loss in this ecosystem, strengthening confidence in our inference (34). These results represent one of the few examples of climate-driven diversity loss in natural communities (1), are the first example from the hyperdiverse flora of the CFR (4), and demonstrate an important interaction between climate change and disturbance by fire that suggests flammable ecosystems, especially those subject to crown fires, may be particularly sensitive to climate change (4, 52).

Species richness of graminoids, herbs, and species that resprout declined in plots that suffered longer spells of CHDs in the first summer after fire, and these spells have increased in duration over the study period. The decline in graminoid and herb species richness is consistent with findings from long-term studies of climate change impacts on Californian grasslands (1) and the Siskiyou mountain herb flora of southern Oregon (30). The observed differences in the response of major growth forms and fire-response types to climate change could well drive major shifts in ecosystem structure and function (13, 17, 18, 31). For example, graminoids and herbs form the majority of the flammable fuel load in Fynbos communities (53), so changes in their cover-abundance may alter fire behavior. Furthermore, the initial recovery of Fynbos vegetation biomass after fire is dominated by graminoids, herbs, and species that resprout (54). Loss of these species would slow initial postfire vegetation recovery, affecting community composition and function by creating a more open light environment, reducing carbon storage and soil integrity, and altering hydrology and the fire regime (18).

The mechanisms driving the observed differences in the response of major growth forms and fire-response types to extreme postfire weather are not clear, but there are several circumstantial lines of evidence that deserve further investigation. First, shrub species have deeper root systems than graminoids and herbs when mature (55), allowing access to deeper water and facilitating transpirational cooling during periods of extreme hot and dry weather. Unfortunately, little is known about the relative rate of root elongation during the establishment phase (29). Second, resprouters typically have lower seed output, seedling growth, and recruitment rates than seeder species (56), and additional climate-induced constraints on seedling establishment may have a greater impact on their ability to recruit new individuals and/or colonize plots than seeder species. Furthermore, greater dependence on persistence makes resprouter demography particularly sensitive to adult mortality (56). Their greater prevalence in wetter Fynbos environments (18, 32, 33) suggests that their decline may in part be due to elevated mortality of resprouting adults as a result of higher temperatures and/or reduced soil moisture.

The additional bottleneck that increasingly extreme weather places on the postfire regeneration phase is concerning because it may compromise the stability of populations and/or further limit species’ abilities to migrate and track shifting climate space (4, 13, 57). Increasing mortality will threaten resprouter species that depend on adult survival for their persistence, whereas the many species in crown-fire ecosystems that can only recruit in the first year after a fire event [most species in our study (20)] are subject to a form of climatic Russian roulette. Although interannual climatic variability may continue to provide years sufficiently benign to allow windows of opportunity for successful regeneration (58), the progressively longer spells of CHDs observed over the past 50 y suggest that these will become increasingly scarce.

The observed shifts toward hotter mean maximum temperature tolerance in the sets of species unique to each survey is consistent with the pattern of “thermophilization” in the tropical forests of the northern Andes and northwestern Colombia reported by Duque et al. (3). Evidence of thermophilization does not indicate the underlying mechanism driving local extinction or colonization, but it does support the notion of climate-driven shifts in the composition of our plots. Duque et al. (3) found that shifts in community-level mean climate tolerances were slightly faster for juvenile trees than adults, but were largely keeping pace with observed climate change. Our communities appear to be lagging, possibly due to adult individuals being more resistant to climate extremes than seedlings or individuals that are actively resprouting. This resistance would lead to delayed, punctuated shifts in composition associated with fires and suggests that the full impact of temperature increases experienced to date is yet to be realized.

In addition to the effects of intensifying postfire weather, there was a clear negative impact of the history of woody alien species invasion on all functional types except geophytes. The impact was far more pronounced when viewed over the full study period, despite the near-complete eradication of woody alien species from the reserve before the 1996 survey (39), suggesting strong “legacy effects” (44) that have continued to impact diversity at our site 30 y after the removal of alien species. The dominant invasives were N-fixing Australian Acacia species that are known to have long-lasting effects on soil chemistry and to reduce indigenous seedbanks (40, 41). The marginally positive response to aliens displayed by geophytes over the initial survey period may have been in response to greater N availability or increased light in the understorey after alien clearing.

We found evidence of diversity loss driven by the interaction between fire and intensifying periods of hot and dry weather overlaying impacts of a historical alien woody plant infestation in the longest existing vegetation plot record for the CFR. Our findings are based on models that consider a range of potential drivers of change and an analysis of species’ climatic niches to infer community-level responses to a/biotic change, and are consistent with multiple existing lines of evidence, including germination and seedling trials (14, 15), and regional vulnerability assessments (59). This study highlights the value of detailed long-term datasets for detecting the influence of multiple global change drivers in unison and for identifying region-specific interactions among change drivers and natural ecological processes (9, 34). The exacerbation of postfire mortality by increasingly severe weather extremes is likely to drive major shifts in the composition, structure, and function of fire-prone ecosystems subject to severe summer droughts and temperature extremes. This is cause for concern given the recent major droughts and temperature extremes suffered in southern Australia, California, and South Africa.

Materials and Methods

All data and R code for all analyses are provided in Datasets S1–S5.

Analysis of Extreme Weather Events.

We used temperature and rainfall records from the Cape Point Global Atmospheric Watch Station situated on the southern tip of the Cape Peninsula (34°21’ S, 18°29’ E, 230 m above sea level) to calculate the maximum number of CHDs (days with <1 mm rainfall and maximum temperatures were in the 90th percentile for the record; 21 °C in this case) for the period 1963–2009 and quantified the trends by using a Bayesian linear model (Fig. 1) (47). CHD was calculated for the period October to March to account for the Austral summer spanning calendar years.

Vegetation Survey Data and Analysis.

The original 1966 study surveyed 100 size 5- 10-m permanently marked plots (46) placed on a grid at 1,000-yard (914 m) intervals. A total of 81 plots were found and resurveyed in 1996 (37), and 63 of these were found and resurveyed in 2010. Because our aim was to explore the effects of fire and postfire weather, we excluded all plots that did not burn in the period 1966–2010 from our analyses, leaving 54 plots. Surveys generated lists of species for each plot, with species scored into one of five abundance classes (37). Plants were positively identified to species wherever possible, and the species lists were updated to current taxonomy (60). Species were classed into fire response type (seeder vs. resprouter) and growth form [geophyte, herb, graminoid, low shrub (<1 m), or tall or medium shrub (>1 m)] following ref. 37, supplemented by literature records and field observations for species first recorded in the 2010 survey. Note that graminoids are typically separated from herbs in Fynbos studies because this component is dominated by species with tough perennial photosynthetic stems and reduced leaves in the families Restionaceae and Cyperaceae (37, 54). The date and number of fires experienced by each plot were obtained from the original surveys (37, 46) and the Table Mountain National Park fire database (23). Data on alien species’ presence and density were obtained from two studies that enumerated all woody alien species in 183-m radii around the plots in 1966 (42) and over the period 1976–1980 (43), ranked into abundance classes of 0; 1–49; 50–199; and 200+ individuals. We used the highest alien abundance class recorded during either survey to characterize the potential effects of invasives.

We performed two sets of analyses on the vegetation survey data using generalized linear mixed-effects models implemented in a Bayesian framework (47), which we repeated for the set of all species and separate subsets for resprouters, seeders, and each of the five growth forms. The first tested whether there was a significant directional decline in species numbers within plots. We fitted raw species counts using a Poisson distribution with vegetation age (at the time of each survey) and survey as fixed effects and plot as a random effect, creating a repeated-measures design. We included vegetation age in the model, because species counts per unit area decline with time since fire in Fynbos because fewer, larger individuals are sampled [i.e., species density declines (48)]. Typically, one should compare species richness estimated by using rarefaction (48), but sensitivity analyses exploring rarefaction based on individual counts estimated from the five abundance classes used in our vegetation surveys suggested that this approach is prone to very large error.

For the second analysis, we tested for evidence of the impacts of a set of potential change drivers on species numbers based on previous evidence (4, 14, 15, 21, 38, 59). Unfortunately, the ubiquitous nature of global change negates the use of control sites to test whether an observed change can be ascribed to a particular cause. As such, we were limited to modeling observed change within sites as a function of spatial differences in the severity of drivers across sites over the period of observation. This generalized linear model was fitted with a Gaussian distribution, because many of the changes in species numbers were negative. Examination of qq-plots supported this approach. We found no evidence of spatial autocorrelation when plotting the autocorrelation function for the response variable and each covariate (in their continuous form). Covariates included change in postfire age between surveys (continuous), the most extreme CHD (2 approximately even categories: 0–5 and 5+; range = 2–8) experienced in the first summer after fire by each plot between vegetation surveys, the maximum alien plant densities (four categories), and the local extinction, stability, or colonization by serotinous tall shrubs (three categories). We did not explore the influence of differences in the number, return time, or season of fires experienced by the plots, because they did not exceed expected natural variation (23).

Models were run with an uninformative inverse-Wishart prior (for multivariate normal data) for 53,000 iterations. Convergence was reached within 3,000 iterations in all cases, and every 10th iteration was sampled thereafter, yielding 5,000 samples for estimation of the posterior means and distributions.

Climate Shifts Based on Regional Species Distribution Records.

We compared the mean maximum temperature tolerance for the sets of all species and species unique to each survey by hierarchically estimating species and then survey means using a Bayesian model assuming Gaussian distributions and uninformative priors (61). Temperature data were extracted from three separate 1 arc minute gridded climatologies (49–51) for all occurrence records in the CFR available from the Pretoria National Herbarium Computerised Information System (PRECIS), with a location accuracy of <2 km for each species (7–1,359 records per species).

SI Text

All data and repeatable R code workflows (R Markdown) used in this study are available in Datasets S1–S5. An updated version fixing any errors etc. will be maintained at 10.6084/m9.figshare.4737358. Code and data are provided under the MIT license, but where possible we would appreciate users acknowledging “the South African Environmental Observation Network (SAEON) and partners” and citing this paper and/or the original data source outlined in the paper. We would also see it as a courtesy to inform the lead author of your intended use of the data. Coauthorship is not a prerequi-site, but we would like to minimize duplication of effort and/or warn users where their plans for the data do not seem appropriate.

Please note that to run the R Markdown workflows you need to delete the .txt file extension (leaving .Rmd). Also note that the R Markdown workflows are currently configured to call data from a .xlsx file to minimize the number of files. This slows down the analyses considerably. If this becomes a constraint, users may consider saving each spreadsheet as a separate .csv file with the name corresponding to the tab name in the workbook. These are available from the link above.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Glenn Moncrieff, Maia Lesosky, Carl Schlichting, Andrew Latimer, and Laure Gallien for useful discussions and comments on an earlier version of the manuscript and South African National Parks for access to the reserve. We are eternally grateful to those who had the wisdom to initiate, compile, and curate this dataset, particularly Hugh Taylor, Ian Macdonald, Sean Privett, Timm Hoffman, and Richard Cowling. This work was supported by NSF Grant DEB-1046328 and the National Research Foundation of South Africa. A.M.W. was supported by NASA Grant NNX16AQ45G.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data are available via Figshare DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.4737358.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1619014114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Harrison SP, Gornish ES, Copeland S. Climate-driven diversity loss in a grassland community. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:8672–8677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502074112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauli H, et al. Recent plant diversity changes on Europe’s mountain summits. Science. 2012;336:353–355. doi: 10.1126/science.1219033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duque A, Stevenson PR, Feeley KJ. Thermophilization of adult and juvenile tree communities in the northern tropical Andes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10744–10749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506570112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altwegg R, West A, Gillson L, Midgley GF. Impacts of climate change in the greater cape floristic region. In: Allsopp N, Colville JF, Verboom GA, editors. Fynbos: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation of a Megadiverse Region. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2014. pp. 299–320. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westerling AL, Hidalgo HG, Cayan DR, Swetnam TW. Warming and earlier spring increase western US forest wildfire activity. Science. 2006;313:940–943. doi: 10.1126/science.1128834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enright NJ, Fontaine JB, Lamont BB, Miller BP, Westcott VC. Resistance and resilience to changing climate and fire regime depend on plant functional traits. J Ecol. 2014;102:1572–1581. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson AM, Latimer AM, Silander JA, Gelfand AE, de Klerk H. A Hierarchical Bayesian model of wildfire in a Mediterranean biodiversity hotspot: Implications of weather variability and global circulation. Ecol Modell. 2010;221:106–112. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson AM, Latimer AM, Silander JAJ. Climatic controls on ecosystem resilience: Postfire regeneration in the Cape Floristic Region of South Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:9058–9063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416710112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franklin J, Serra-diaz JM, Syphard AD, Regan HM. Global change and terrestrial plant community dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:3725–3734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519911113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bond WJ, Van Wilgen BW. Fire and Plants. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 1996. p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowman DMJS, et al. Fire in the earth system. Science. 2009;324:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1163886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mouillot F, Rambal S, Joffre R. Simulating climate change impacts on fire frequency and vegetation dynamics in a Mediterranean-type ecosystem. Glob Change Biol. 2002;8:423–437. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walck JL, Hidayati SN, Dixon KW, Thompson K, Poschlod P. Climate change and plant regeneration from seed. Glob Change Biol. 2011;17:2145–2161. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mustart P, Rebelo AG, Juritz J, Cowling R. Wide variation in post-emergence desiccation tolerance of seedlings of Fynbos proteoid shrubs. S Afr J Bot. 2012;80:110–117. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnolds JL, Musil CF, Rebelo AG, Krüger GHJ. Experimental climate warming enforces seed dormancy in South African Proteaceae but seedling drought resilience exceeds summer drought periods. Oecologia. 2015;177:1103–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00442-014-3173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Wilgen BW, Richardson DM. The effects of alien shrub invasions on vegetation structure and fire behavior in South-African fynbos shrublands - A simulation study. J Appl Ecol. 1985;22:955–966. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson DM, Cowling R, Bond W, Stock W, Davis GW. Links between biodiversity and ecosystem function in the Cape Floristic Region. In: Davis GW, Richardson DM, editors. Mediterranean-Type Ecosystems: The Function of Biodiversity. Springer; New York: 1995. pp. 285–333. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slingsby JA, Ackerly DD, Latimer AM, Linder HP, Pauw A. The assembly and function of Cape plant communities in a changing world. In: Allsopp N, Colville J, Verboom GA, editors. Fynbos: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation of a Megadiverse Region. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2014. pp. 200–223. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature. 2000;403:853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Maitre DC, Midgley JJ. Plant reproductive ecology. In: Cowling RM, editor. The Ecology of Fynbos: Nutrients, Fire and Diversity. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 1992. pp. 135–174. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraaij T, van Wilgen BW. Drivers, ecology, and management of fire in fynbos. In: Allsopp N, Colville JF, Verboom GA, editors. Fynbos: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation of a Megadiverse Region. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2014. pp. 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Wilgen BW, Richardson DM, Kruger FJ, van Henbergen HJ. 1992. Fire in South African Mountain Fynbos: Ecosystem, Community and Species Responses at Swartboskloof, Ecological Studies (Springer, New York) no 93, p 325.

- 23.Forsyth GG, van Wilgen BW. The recent fire history of the Table Mountain National Park and implications for fire management. Koedoe. 2008;50:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frazer JM, Davis SD. Differential survival of chaparral seedlings during the first summer drought after wildfire. Oecologia. 1988;76:215–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00379955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman MT, Cramer MD, Gillson L, Wallace M. Pan evaporation and wind run decline in the Cape Floristic Region of South Africa (1974–2005): Implications for vegetation responses to climate change. Clim Change. 2011;109:437–452. [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacKellar N, New M, Jack C. Observed and modelled trends in rainfall and temperature for South Africa: 1960 – 2010. S Afr J Sci. 2014;110:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Wilgen NJ, Goodall V, Holness S, Chown LS, McGeoch MA. Rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns in South Africa’ s national parks. Int J Climatol. 2016;36:706–721. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schurr FM, Esler KJ, Slingsby JA, Allsopp N. Fynbos proteaceae as model organisms for biodiversity research and conservation. S Afr J Sci. 2012;108:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustart P, Cowling R. Seed size: Phylogeny and adaptation in two closely related proteaceae species-pairs. Oecologia. 1992;91:292–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00317799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrison S, Damschen EI, Grace JB. Ecological contingency in the effects of climatic warming on forest herb communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19362–19367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006823107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeppel MJ, et al. Drought and resprouting plants. New Phytol. 2015;206:583–589. doi: 10.1111/nph.13205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ojeda F. Biogeography of seeder and resprouter erica species in the Cape Floristic Region—where are the resprouters? Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 1998;63:331–347. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wüest RO, et al. Resprouter fraction in Cape Restionaceae assemblages varies with climate and soil type. Funct Ecol. 2016;30:1583–1592. [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Connor MI, et al. Strengthening confidence in climate change impact science. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2015;24:64–76. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raimondo D, et al. Red list of South African plants 2009. South African National Biodiversity Institute; Silverton, South Africa: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cowling R, Gxaba T. Effects of a Fynbos overstorey shrub on understorey community structure: Implications for the maintenance of community-wide species richness. S Afr J Ecol. 1990;1:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Privett SDJ, Cowling RM, Taylor HC. Thirty years of change in the Fynbos vegetation of the Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve, South Africa. Bothalia. 2001;31:99–115. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richardson D, Macdonald I, Hoffmann J, Henderson L. Alien plant invasions. In: Cowling R, Richardson D, Pierce S, editors. Vegetation of Southern Africa. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1997. pp. 535–570. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macdonald I, Clark D, Taylor H. The history and effects of alien plant control in the Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve, 1941-1987. S Afr J Bot. 1989;55:56–75. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yelenik SG, Stock WD, Richardson DM. Ecosystem level impacts of invasive Acacia saligna in the South African fynbos. Restoration Ecol. 2004;12:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le Maitre DC, et al. Impacts of invasive Australian acacias: Implications for management and restoration. Divers Distrib. 2011;17:1015–1029. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor HC, Macdonald SA. Invasive alien woody plants in the Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve. I. Results of a first survey in 1966. S Afr J Bot. 1985;51:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor HC, Macdonald SA, Macdonald IAW. Invasive alien woody plants in the Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve. II. Results of a second survey from 1976 to 1980. S Afr J Bot. 1985;51:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 44.D’Antonio C, Meyerson LA. Exotic plant species as problems and solutions in ecological restoration: A synthesis. Restoration Ecol. 2002;10:703–713. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simmons MT, Cowling RM. Why is the Cape Peninsula so rich in plant species? An analysis of the independent diversity components. Biodivers Conserv. 1996;5:551–573. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor HC. A vegetation survey of the Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve. I. The use of association-analysis and Braun-Blanquet methods. Bothalia. 1984;15:245–258. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hadfield J. MCMC methods for multi-response generalized linear mixed models: The MCMCglmm R package. J Stat Softw 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gotelli NJ, Colwell RK. Quantifying biodiversity: Procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol Lett. 2001;4:379–391. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 2005;25:1965–1978. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schulze RE. 2007. South African Atlas of Climatology and Agrohydrology (Water Research Commission, Pretoria, South Africa), RSA, WRC Report 1489/1/06, Tech Rep.

- 51.Wilson AM, Silander JA. Estimating uncertainty in daily weather interpolations: A Bayesian framework for developing climate surfaces. Int J Climatol. 2014;34:2573–2584. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yates CJ, et al. Projecting climate change impacts on species distributions in megadiverse South African Cape and Southwest Australian Floristic Regions: Opportunities and challenges. Austral Ecol. 2010;35:374–391. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Wilgen B. Adaptation of the United States fire danger rating system to Fynbos conditions. Part i. a fuel model for fire danger rating in the Fynbos biome. S Afr J For. 1984;129:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rutherford M, Powrie L, Husted L, Turner R. Early post-fire plant succession in Peninsula Sandstone Fynbos: The first three years after disturbance. S Afr J Bot. 2011;77:665–674. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Higgins K, Lamb A, Van Wilgen B. Root systems of selected plant species in mesic mountain Fynbos in the Jonkershoek Valley, south-western Cape Province. S Afr J Bot. 1987;53:249–257. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bond WJ, Midgley JJ. The evolutionary ecology of sprouting in woody plants. Int J Plant Sci. 2003;164:S103–S114. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Corlett RT, Westcott DA. Will plant movements keep up with climate change? Trends Ecol Evol. 2013;28:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Serra-Diaz JM, et al. Averaged 30 year climate change projections mask opportunities for species establishment. Ecography. 2016;39:844–845. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Midgley GF, Hannah L, Millar D, Thuiller W, Booth A. Developing regional and species-level assessments of climate change impacts on biodiversity in the Cape Floristic Region. Biol Conserv. 2003;112:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manning J, Goldblatt P. Plants of the Greater Cape Floristic Region 1: The Core Cape Flora, Strelitzia 29. South African National Biodiversity Institute; Pretoria, South Africa: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martin AD, Quinn KM, Park JH. MCMCpack: Markov chain monte carlo in R. J Stat Softw. 2011 doi: 10.18637/jss.v042.i09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.