Significance

Honey bees are globally important plant pollinators. Guts of adult workers contain specialized bacteria not found outside bees. Experimental results show that gut bacteria increase weight gain in young adult bees, affect expression of genes governing insulin and vitellogenin levels, and increase sucrose sensitivity. Gut bacteria also shape the physicochemical conditions within the gut, lowering pH and oxygen levels. Peripheral resident bacteria consume oxygen, thus maintaining anoxia, as required for microbial activity. Additionally, gut bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids, with acetate and propionate as the major metabolites, as in guts of human and other animals. This study demonstrates how bacteria in the honey bee gut affect host weight gain and improves our understanding of how gut symbionts influence host health.

Keywords: honeybee, gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, insulin, metabolomics

Abstract

Social bees harbor a simple and specialized microbiota that is spatially organized into different gut compartments. Recent results on the potential involvement of bee gut communities in pathogen protection and nutritional function have drawn attention to the impact of the microbiota on bee health. However, the contributions of gut microbiota to host physiology have yet to be investigated. Here we show that the gut microbiota promotes weight gain of both whole body and the gut in individual honey bees. This effect is likely mediated by changes in host vitellogenin, insulin signaling, and gustatory response. We found that microbial metabolism markedly reduces gut pH and redox potential through the production of short-chain fatty acids and that the bacteria adjacent to the gut wall form an oxygen gradient within the intestine. The short-chain fatty acid profile contributed by dominant gut species was confirmed in vitro. Furthermore, metabolomic analyses revealed that the gut community has striking impacts on the metabolic profiles of the gut compartments and the hemolymph, suggesting that gut bacteria degrade plant polymers from pollen and that the resulting metabolites contribute to host nutrition. Our results demonstrate how microbial metabolism affects bee growth, hormonal signaling, behavior, and gut physicochemical conditions. These findings indicate that the bee gut microbiota has basic roles similar to those found in some other animals and thus provides a model in studies of host–microbe interactions.

Honey bees (Apis mellifera) provide a critical link in global food production as pollinators of agricultural crops (1), and their economic value is over $15 billion annually in the United States alone (2). Honey bee populations have undergone elevated colony mortality during the last decade in the United States, Canada, and Europe (3). A potential role of gut microbial communities in the health of honey bees has recently become more widely appreciated (4). Perturbation of the gut microbiota leads to higher mortality within hives and greater susceptibility to a bacterial pathogen, suggesting a crucial role of normal microbiota in bee health (5). Honey bees are associated with specific intestinal microbiota that is simpler than the microbiota found in mammals but shares some features, including host specificity and social transmission (6) and a shared evolutionary history of bacterial and host lineages (7, 8). The bee gut is dominated by eight core bacterial species that are spatially organized within specific gut regions. Few bacteria colonize the crop and midgut; the hindgut (ileum and rectum) harbors the greatest abundance of bacteria. The ileum, a narrow tube with six longitudinal folds, is dominated by two Gram-negative bacterial species: Snodgrassella alvi, a nonsugar fermenter forms a layer directly on the gut wall, together with Gilliamella apicola, a sugar fermenter that resides more toward the center of the lumen (9). The distal rectum is dominated by the Gram-positive Lactobacillus spp (10).

In both insects and mammals, the gut microbiota can possess a large repertoire of metabolic capabilities and can contribute substantively to dietary carbohydrate digestion within the intestinal ecosystem (11). Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), namely acetate, propionate, and butyrate, produced by the gut microbiota as main fermentation products of dietary fiber accumulate in the human colon in concentrations up to 80–130 mM (12) and serve as a major energy source for intestinal epithelial cells (13) or as the main respiratory substrate of the host (14). Moreover, microbial metabolites can have a profound effect on gut physiology; for example, their effects on oxygen concentration, pH, and redox potential can be essential for host health (15). As neuroactive compounds, SCFAs produced by the gut microbiota can affect neural and immune pathways of the host and thereby influence brain function and behavior (16).

In the case of honey bees, genome-based investigations showed that G. apicola strains potentially digest complex carbohydrates (i.e., pectin from pollen cell wall) that are otherwise indigestible by the host (17). A recent study documents that G. apicola strains can also use several sugars that are harmful to bees (18). However, how the bee gut microbiota affects host physiology and the gut microenvironment has not yet been described. Hence, we compared germ-free (GF) honey bees to those with a conventional gut community (CV) to identify how the gut microbiota affects weight gain, expression of genes underlying hormonal pathways, gut physicochemical conditions, and metabolite pools in the gut and hemolymph.

Results and Discussion

Gut Microbiota Promotes Host Body and Gut Weight Gain.

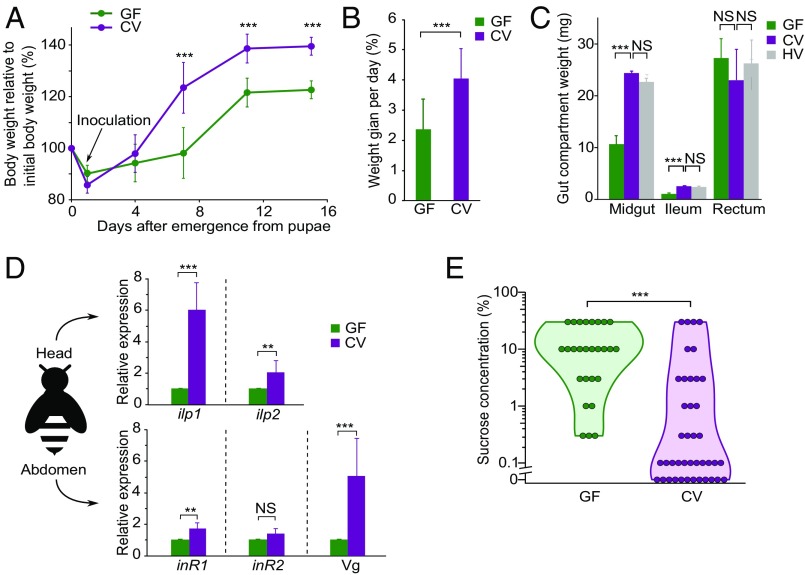

To observe effects of the microbiota on growth of individual hosts, we performed serial measurements of whole-body wet weight in the presence and absence of the gut microbiota. GF and CV bees were obtained from pupae that were removed from hives, allowed to emerge in sterile laboratory conditions, and then fed either sterilized food or sterilized food inoculated with the gut content of conventional adult nurse bees. This procedure yields GF bees with <105 bacteria per gut consisting of an erratic mix of bacterial species versus CV bees with >108 bacteria per gut and consisting primarily of core bee gut species, as in naturally inoculated hive bees (19, 20). Although GF and CV bees showed similar survivorship in laboratory experiments, CV bees attained greater body weight (Fig. 1A) and achieved a weight gain 82% higher than that of GF bees (Fig. 1B). After 15 d, the wet weights of both midgut and ileum were also larger in CV bees than in GF bees and were similar to those of nurse bees collected from hives (Fig. 1C). In contrast, rectum weights were not significantly different and were more variable, probably because of variable levels of pollen and waste accumulation in this gut compartment (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that the presence of conventional gut microbiota is required for normal body and gut weight gain during the days following emergence from the pupal stage. A similar effect of gut microbiota has been documented in humans and mice (21, 22), and the commensal microbiota also influences the systemic development of Drosophila (23). Although the fitness effects of this weight gain were not measured directly at the colony level, several observations suggest that the greater increase in weight in the presence of microbiota is beneficial. As observed in previous studies, all bees gained weight during the first 10 d following emergence (24), but we found that the gain was almost halved for bees deprived of gut microbiota (Fig. 1A). Larger mass may assist in the initial tasks as nurses within the hive, whereas older bees (>20 d) are known to lose weight as they transition to foraging (24, 25).

Fig. 1.

Gut microbiota increases honey bee whole-body weight, gut weight, hormonal signaling, and sucrose sensitivity. (A) Whole-body wet weight growth curves of GF (n = 45) and CV bees (n = 49) originated from four different hives (the colony of origin was not statistically significant). (B) Daily weight gains of GF and CV bees after feeding with sterilized food or food supplemented with hindgut samples of hive nurse bees (day 1 to day 15). (C) Weights of different gut compartments of GF, CV, and hive nurse bees (n = 25). Bars indicate mean values of 10–15 pooled guts of bees from different hives (GF, n = 4; CV, n = 4) and hive bees from different hives (n = 3). (D) Differential expression of ilp, inR, and Vg genes in the head or abdomen of GF and CV bees originating from different hives. n = 3. (E) Distribution of sucrose-response thresholds of GF (n = 27) and CV (n = 41) bees shown as a violin plot. The colony of origin was not statistically significance. Each circle indicates a bee response to the provided concentration of sucrose. In A–D, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (Mann–Whitney u test for the indicated comparisons); error bars indicate SD. In E, ***P < 0.001 (χ2 test). NS, not significant.

Insulin/Insulin-Like Signaling and Sucrose Sensitivity.

Weight gain in honey bees has been shown to be associated with insulin insulin/insulin-like signaling (IIS) (26). The IIS pathway plays a key role in insect growth, reproduction, and aging (27) and is a regulator of nutrient homeostasis and behavior in honey bees (28, 29). The honey bee genome contains genes encoding two insulin-like peptides (ILPs) and two putative insulin receptors (InRs) for these peptides (30). In addition, vitellogenin (Vg), an egg yolk protein, interacts with the IIS pathway to regulate bee nutritional status (31). The ILPs are preferentially expressed in the heads of worker bees, whereas InRs and Vg are more highly expressed in abdomens (32).

We examined the expression levels of the two ILP genes (ilp1 and ilp2) in heads of 7-d-old bees and of two InR genes (inR1 and inR2) and one Vg gene in the abdomens of the same bees. The ilp1 and Vg genes were expressed 5.8 and 4.9 times higher in CV than in GF bees, respectively, and ilp2 and inR1 also increased expression in CV bees (Fig. 1D). Thus, CV bees have enhanced insulin production and responsiveness. The IIS pathway responds to diet, and ilp1 expression is highest on a protein-rich diet; moreover, bees fed on this diet obtain more body weight (26). Our results suggest that the gut bacteria supply amino acids, which increase IIS gene expression and weight gain. Bees on high-protein diets exhibit harmful weight gain and short lifespans (26); however, the similar survival of CV and GF bees indicates that the weight gain of CV bees does not affect longevity. In contrast, the expression of inR2 was not significantly altered, suggesting that it is unresponsive to nutrient manipulations as shown for ilp2 (33, 34).

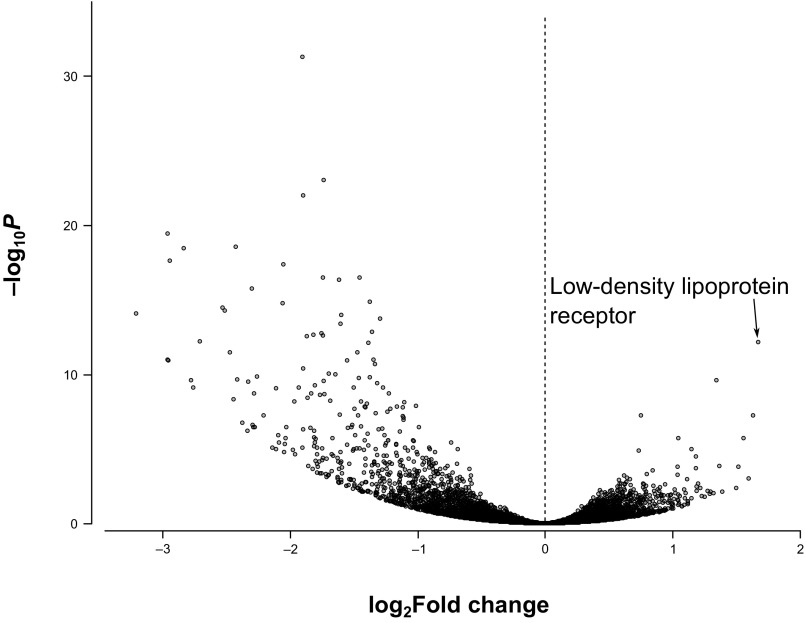

We also determined how the presence of microbiota impacts the overall transcriptome of gut epithelial cells. Of 10,189 genes detected in the RNA sequencing analysis, 221 host genes are significantly more highly expressed in CV bees (Dataset S1). Interestingly, the most significantly up-regulated gene belongs to the low-density lipoprotein receptor superfamily (Fig. S1 and Dataset S1), which encodes the Vg receptor in Drosophila (35). However, the Vg receptor is usually expressed in the ovary, suggesting that the transcripts originated from the residue of ovaries with the dissected guts. Nevertheless, such stimulation is consistent with the increase in Vg expression in the abdomen.

Fig. S1.

Comparison of transcript expression profiles of honey bee genes in CV and GF bees. The volcano plot reports the fold change (CV/GF) of transcripts between the samples. n = 3.

The IIS pathway regulates the behavior of worker honey bees, including division of labor and sucrose sensitivity (29, 36). Sucrose sensitivity is an indicator of energy status and satiety in honey bees (37). By measuring the proboscis extension response of both CV and GF bees (Movie S1), we found that the gut microbiota significantly elevates sucrose sensitivity: More CV bees responded to lower concentrations of sucrose (i.e., CV bees are “hungrier” than GF bees) (Fig. 1E). Our combined results provide evidence that the gut microbiota of honey bees stimulates IIS and Vg expression, which in turn affects bee satiety and ultimately promotes host weight gain. This observation is consistent with results showing that IIS promotes growth in other gut microbiota models such as Drosophila (23) and mammals (38).

Physicochemical Conditions.

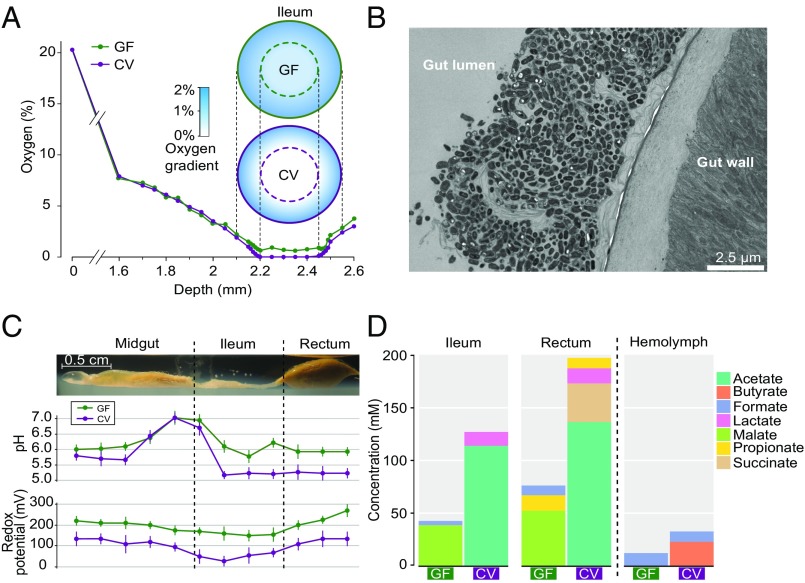

The intestines of insects together with their symbiotic microbes can be viewed as minute ecosystems characterized by complex physicochemical conditions. We examined these conditions in the bee gut by using Clark-type, glass pH and Redox electrodes with a tip size of 50 µm to measure the oxygen status, pH, and redox potential in each gut compartment. All compartments of CV bee guts and the midgut and rectum of GF bees were entirely anoxic (0% oxygen) in their centers. In contrast, trace oxygen was detected in the center of the ileum of GF bees (Fig. 2A). For a more fine-grained view of how the microbiota affects oxygen levels within the ileum, we determined the radial oxygen profiles for the ileums of GF and CV bees. Oxygen concentration in the CV ileum the decreased rapidly from the gut wall inward, reaching 0% when the microsensor tip was only about 150–200 μm below the exterior surface of the gut wall. Thus, the ileums of CV bees contain a microoxic periphery around an anoxic center (Fig. 2A). By contrast, oxygen concentration was still 1% in the center of the GF ileum. Although gut epithelial cells can contribute to oxygen consumption, the different oxygen gradients of CV and GF ileums indicate that the major oxygen consumers must be resident bacteria in the peripheral region of the gut lumen.

Fig. 2.

Physicochemical conditions and SCFA profiles in the guts of GF and CV bees. (A) Radial profiles of oxygen concentration in the ileum of GF (n = 3) and CV (n = 3) honey bees from different hives. The central regions of CV ileums are always absolutely anoxic (0% oxygen). Deviation for each value is typically less than 0.2% oxygen. Depth refers to the distance between the electrode tip and the surface of the agarose. The schematic representation of the oxygen concentration gradient shows a microoxic periphery around the anoxic center in the CV bee ileum, whereas oxygen is present even in the center of the GF bee ileum. (B) Transmission electron micrographs of the CV ileum epithelium with a bacterial layer. (C) Microelectrode profiles of pH and redox potential along the GF and CV gut axis. The gut was embedded in a microchamber with agarose. Samples are originated from different hives, but colony of origin was not statistically significant. Error bars indicate SD (n = 4). (D) Concentrations of SCFA in the ileum, rectum, and hemolymph of GF and CV honey bees. Samples are originated from different hives; colony of origin was not statistically significant. A full list of concentration values is shown in Table S1.

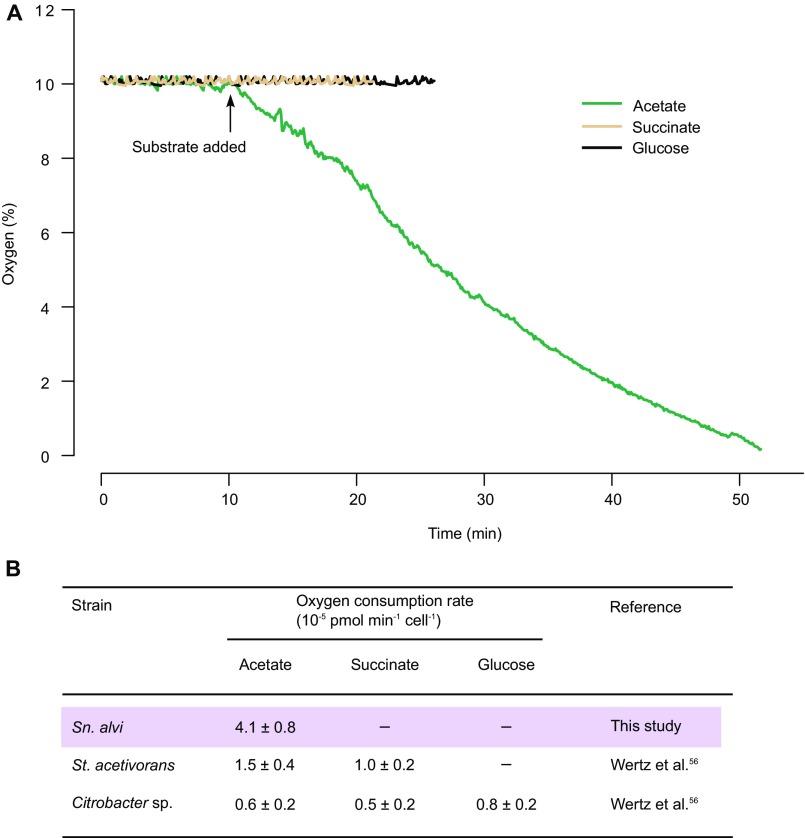

A favorable, anoxic environment is crucial for the anaerobic microorganisms in most animals’ digestive tracts (39). Anoxia can be accomplished easily when the intestinal volume is large, and the ileums of honey bees possess a surface area:volume ratio of 6,700 m2/m3 that is much larger than that of human intestine or rumen (40). The inner wall of the honey bee ileum is associated with a bacterial layer formed by S. alvi (10), a non–sugar-fermenting Betaproteobacteria (Fig. 2B). The observed sharp drop in oxygen might result from S. alvi’s consumption of oxygen penetrating from outside or secreted from host tissue. This idea is supported by in vitro tests showing that S. alvi uses acetate to fuel its oxygen-consuming respiratory activity (Fig. S2A), as shown for gut wall-colonizing bacteria in human (41). The O2 consumption rate of S. alvi wkB2 is 4.1 ± 0.8 × 10−5 pmol⋅min−1⋅cell−1 in buffer supplemented with acetate, which is higher than that of Stenoxybacter acetivorans, an O2 consumer located in the peripheral region of termite hindguts, and that of Citrobacter sp. strain RFC-10 (Fig. S2B) (42). Not surprisingly, no O2 was consumed in succinate- or glucose-supplemented buffer, because S. alvi does not use these as energy sources (Fig. S2A). S. alvi is an obligate aerobe (9), and genome-wide transposon insertion (Tn-Seq) screening has shown that the ntrX/ntrY two-component oxygen sensor is essential for host colonization (43). Considering the high abundance, peripheral localization in the gut, obligately aerophilic nature (9), and restriction to acetate as oxidizable energy sources, S. alvi must be responsible for the maintenance of anoxia in the gut, which is crucial for appropriate metabolism of other gut symbionts.

Fig. S2.

Oxygen consumption of Snodgrassella alvi strain wkB2. (A) Substrate-specific oxygen consumption of S. alvi. (B) The oxygen consumption rate of S. alvi strain wkB2 compared with that of S. acetivorans and Citrobacter sp. strain RFC-10 on different substrates. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3).

The bee gut microbiota also causes both reduced pH and redox potential (Fig. 2C), reflecting bacterial metabolic activity. Axial profiles of pH showed greater acidity in CV bees than in GF bees in the center of each gut region, whereas the pH increases along the midgut and decreases toward the ileum and rectum in both (Fig. 2C). Especially in the ileum and rectum, where most bacteria localize, the pH values are lower in CV bees (around 5.2) than in GF bees (around 6.0), suggesting that the difference reflects microbial activity. In both types of guts, the redox potential is positive throughout the gut even though the gut is anoxic (Fig. 2C). In experiments on mammalian systems, colonic pH and redox status have important physiological effects on Ca2+ availability and on the composition of the gut community (44). A major cause of this reduced colonic pH is active fermentation resulting in significant increase of SCFAs (45).

Gut Metabolites.

We investigated the composition of SCFAs in gut compartments of GF and CV bees. The metabolite pools from the different gut compartments differ strongly between GF and CV bees, demonstrating the role of the gut microbiota as the main producer of SCFA in vivo (Fig. 2D). In the CV ileum and rectum, the prevailing fermentation product is acetate (114–137 mM) (Table S1), which also is the most abundant SCFA observed in human intestine (46) and which has been shown to enhance gut epithelial barrier functions (47). By contrast, GF ileum and rectum show accumulation of malate, although in lower amounts; succinate was present only in CV rectum (Table S1). Thus, the gut microbiota impacts host physiology. Because the redox potentials are always positive, we did not detect hydrogen production in the guts. In all compartments of the GF gut, the homogenates contain high concentrations of glucose and fructose. However, these sugars are much lower in the homogenates of CV ileums and rectum, indicating that they are consumed by the symbiotic bacteria. Hemolymph metabolite profiles also differ between CV and GF bees, suggesting that gut bacteria affect host metabolism. Although trace amounts of formate were detected in hemolymph of both CV and GF bees, butyrate (22.8 mM) was detected only in the CV hemolymph. In mammals, butyrate is an important fermentation product produced by the gut microbiota (48) and has been shown to serve as the main energy source for colonocytes (49). The absence of butyrate in the bee gut suggests that it is absorbed and used by the host.

Table S1.

Gut metabolites of GF and CV honey bees of the same age group from three different hives (15 d after emergence)

| SCFA, mM | Monosaccharide, mM | |||||||||

| Sample | CV or GF | Acetate | Lactate | Succinate | Propionate | Malate | Formate | Butyrate | Glucose | Fructose |

| Hemolymph | CV | – | – | – | 0.1 | – | 9.8 | 22.8 | 29.1 | 103.4 |

| GF | – | – | – | – | – | 12.2 | – | 28.7 | 39.3 | |

| Midgut | CV | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 156.3 | 81.9 |

| GF | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 206.2 | 98.4 | |

| Ileum | CV | 114.0 | 13.2 | – | – | – | – | – | 67.4 | 5.4 |

| GF | – | – | – | – | 38.7 | 4.0 | – | 158.8 | 54.3 | |

| Rectum | CV | 136.5 | 14.4 | 36.7 | 9.9 | – | – | – | 7.3 | 4.1 |

| GF | – | – | – | 14.7 | 52.4 | 9.2 | – | 45.2 | 24.8 | |

Values are means ± SD of biological replicates from different cup cages (n = 3; less than 10% deviation); –, under the detection limit.

The different gut fermentation profiles between GF and CV bees might be shaped by oxygen status, as shown in cockroaches (50). Indeed, in in vitro cultures of the two most abundant bee gut fermenters, G. apicola and Lactobacillus sp., fermentation products were strongly dependent on oxygen status (Tables S2 and S3), clarifying the differences in gut SCFA profiles (Fig. 2D). The major fermentation product of G. apicola under ambient air is malate, but with decrease of O2, G. apicola shifts to producing more acetate and propionate (Table S2), as is consistent with the in situ results. Although Lactobacillus species are considered to be lactic acid producers (51), they produce substantial amounts of acetate when headspace contains 2% of O2 (Table S3). The shift from lactate to acetate formation with the presence of O2 has been documented in Enterococcus strain RfL6 from termite gut (52). Our results indicate that the resident gut bacteria contribute to the major SCFAs detected in the hindgut.

Table S2.

Fermentation products of G. apicola strain wkB1 cultivated under different oxygen concentrations

| Oxygen concentration, %* | Product, mol/mol fructose consumed | |||||

| Malate | Succinate | Lactate | Formate | Acetate | Propionate | |

| 21 | 1.41 | – | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.21 | – |

| 8 | 0.15 | – | 0.47 | – | 0.46 | 0.45 |

| 2 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.49 |

| 0 | 0.21 | 0.98 | 0.16 | – | – | 0.64 |

Values are means of replicate cultures (n = 3; less than 10% deviation); –, under detection limit.

Initial oxygen concentration in the headspace of culture tubes (vol/vol).

Table S3.

Fermentation products of Lactobacillus sp. strain wkB8 cultivated under different oxygen concentrations

| Oxygen concentration, %* | Product, mol/mol fructose consumed | |||

| Lactate | Acetate | Propionate | Butyrate | |

| 8 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.27 |

| 2 | 1.2 | 0.72 | 0.37 | 0.35 |

| 0† | 1.3 | 0.15 | 0.38 | 0.36 |

Values are means of replicate cultures (n = 3; less than 10% deviation).

Initial oxygen concentration in the headspace of culture tubes (vol/vol).

Strain wkB8 does not grow in the DTT-reduced medium or with 21% oxygen in the headspace.

Metabolomics.

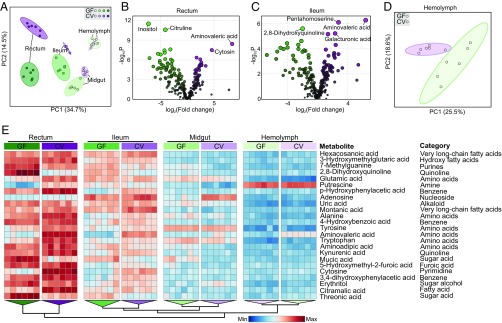

For a more in-depth understanding of the effects of gut microbiota, we compared metabolite levels in separate gut compartments and hemolymph for CV and GF bees using untargeted metabolomics by GC–MS analysis. The principal component analysis (PCA) showed that the gut microbiota has a striking effect on the gut metabolome, especially in the rectum and ileum (Fig. 3 A and E), where most gut bacteria reside (10). By contrast, hemolymph samples were not clearly distinct between CV and GF bees. In the ileum and rectum, aminovaleric acid is the compound most elevated in CV bees in both the ileum (319-fold) and rectum (84-fold) (Fig. 3 B and C and Dataset S2, A and B). Aminovaleric acid is also a major product of microbial activity in the human gut (53). Another notable enrichment in the CV ileum is for galacturonic acid (Fig. 3C), the main constituent of pectin, indicating pectin degradation by gut bacteria and corroborating the presence of genes encoding enzymes that target pollen wall polysaccharides (17). Galacturonic acid was not enriched in the CV rectum, suggesting that it is degraded by the dense bacterial community. This result is consistent with the ability of G. apicola strains to use products of pectin degradation (18). In CV bees, adenosine was elevated within the midgut, despite the very low levels of bacteria colonizing this gut compartment (Fig. 3E and Dataset S2C). Potentially gut colonization triggers endogenous production of adenosine, which may reduce gut inflammation (54).

Fig. 3.

Metabolomic analysis of different gut compartments of GF and CV bees. (A) Results of PCA based on 795 metabolites (Dataset S3) detected from three gut compartments and hemolymph of GF (n = 6) and CV (n = 6) bees showing different clustering groups (95% confidence regions) according to the presence of gut microbiota. (B and C) Differentially regulated metabolites in rectum (B) and ileum (C). The metabolites enriched in CV bees are shown in purple, and those enriched in GF bees are in green. The area and color of each circle are proportional to the significance (−log10 P). Full lists of the values in all gut compartments and hemolymph are given in Dataset S2 A–D. (D) Results of PCA based on all metabolites detected in hemolymph of GF and CV bees (excluding gut compartments from the analysis). (E) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering heat map of the 25 metabolites that contribute most to the separation of hemolymph, midgut, ileum, and rectum. Each column represents one sample. Colors indicate the normalized relative concentration of each metabolite (minimum–maximum). The tree on the bottom illustrates a dendrogram of clustering (Ward’s method).

Although the impact on hemolymph is less than that on gut compartments, when we analyzed the hemolymph samples separately the metabolite profiles also show a clear effect of gut microbiota (Fig. 3D). Several amino acids are elevated in CV hemolymph (Dataset S2D), suggesting that they are absorbed by the host. Based on a previous mutational screen (43), biosynthetic pathways for amino acids are crucial for host colonization, suggesting that gut bacteria might contribute amino acids absorbed by the host. Alternatively, host pathways for vitamin and amino acid biosynthesis are among those significantly up-regulated in CV bees (Fig. S3), suggesting that the presence of gut microbiota stimulates host metabolism. The increased quantities of amino acids in the CV hemolymph might reflect the stimulation of the IIS pathway and subsequent weight gain, which has been linked to an amino acid-supplemented food in honey bees (26). Thus, gut symbionts may supply sufficient protein to affect hormonal signaling and to promote weight gain of the hosts.

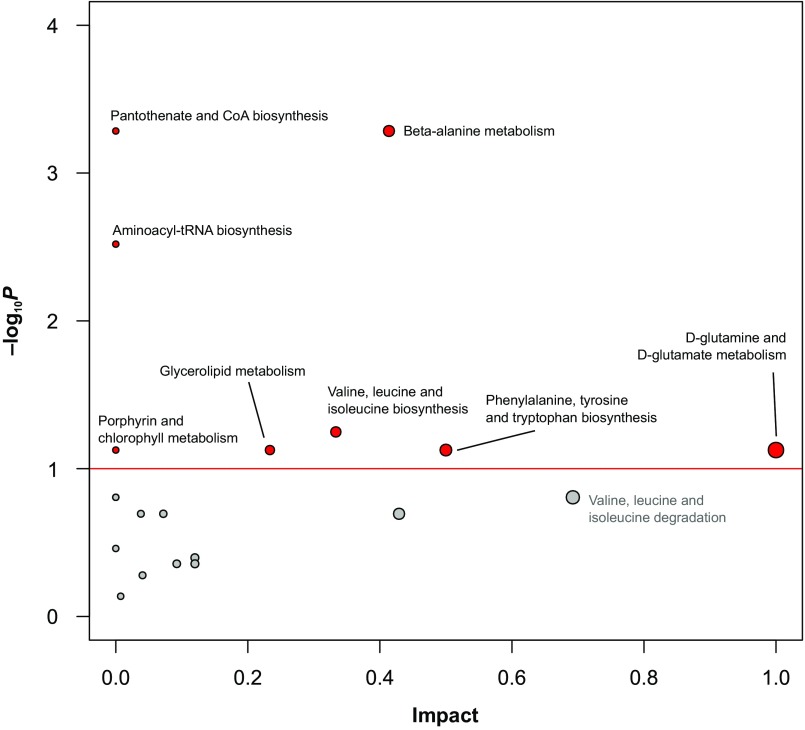

Fig. S3.

Pathway enrichment analysis based on the metabolome profiles of GF and CV hemolymph using a hypergeometric test and pathway impact which incorporates pathway topology (e.g., if metabolites cover key position in the respective pathway). By using a false discovery rate threshold of 0.1 on both metabolite level and pathway level, eight pathways were declared to be significant and thus influenced by the presence of the gut microbiota. These pathways include vitamin and amino acid biosynthesis. It could not be conclusively clarified whether these compounds result from an induced host activity or stem from the gut symbionts.

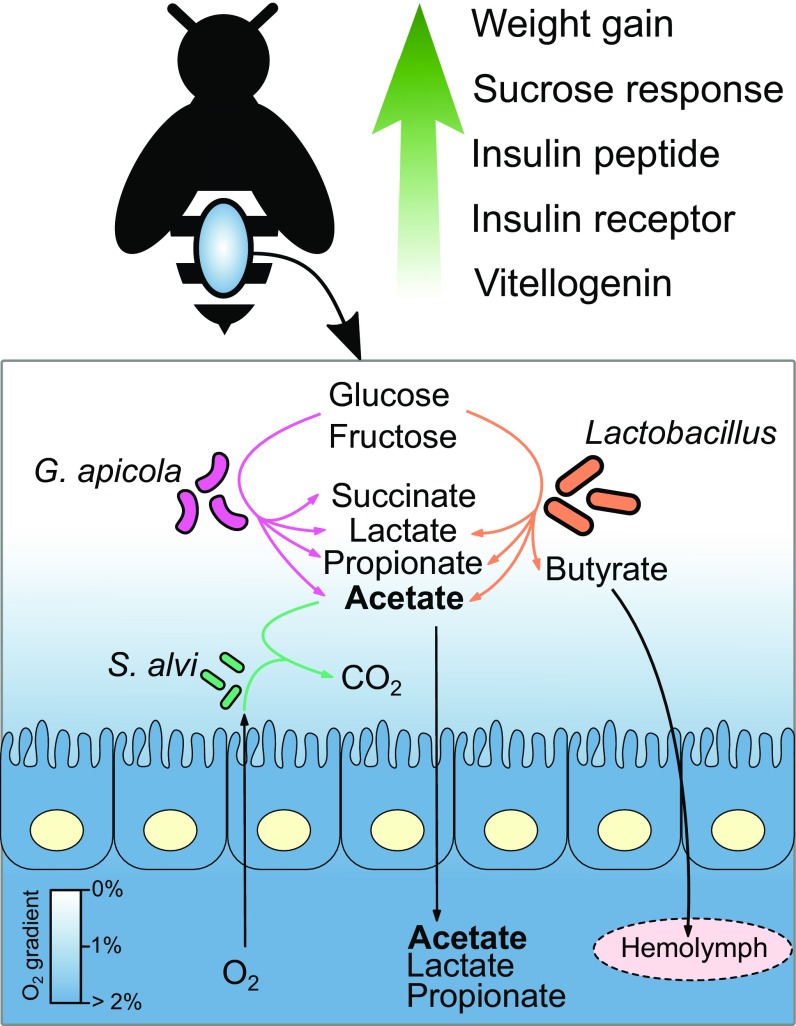

Conclusions

Our results show that the gut microbiota of young adult honey bees promotes weight gain and that this effect is accompanied by the enhanced expression of genes affecting hormonal titers and by an increased sensitivity to sugar (Fig. 4). In addition, spatially organized microbial communities maintain an oxic–anoxic gradient in the gut with lowered pH and redox potential, effects similar to those demonstrated for the human gut microbiota (11). Our observations of the involvement of gut bacteria in the maintenance of gut physicochemical characteristics, SCFA production, and the digestion of complex dietary components (e.g., pectin) reveal further similarities between the gut microbiota of humans and honey bees and provide perspectives for future studies using the bee gut model for investigating host–microbe interactions. Further experimental work is needed to determine the extent to which similar cellular mechanisms underlie the observed similarities of gut microbiota in these different animal hosts.

Fig. 4.

Graphical summary of the main results. The conventional gut microbiota, including the major sugar fermenters G. apicola and Lactobacillus sp., produce SCFAs, which promote host growth. The gut wall-associated S. alvi uses acetate, the most abundant SCFA in the hindgut, to remove efficiently O2 penetrating into the gut and to maintain a stable O2 gradient. The presence of gut microbiota stimulated host weight gain, host sucrose sensitivity, and increased expression of genes related to hormonal signaling.

Materials and Methods

Detailed protocols are available in SI Materials and Methods. GF and CV bees were obtained using the protocol described by Powell et al. (19). We obtained GF bees by removing pupae from brood frames of four different hives and allowing bees from each hive to emerge in a separate, sterile dish. CV bees were obtained by feeding newly emerged bees with homogenates of hindguts of nurse bees from their original hive. This inoculation method was chosen because it yields CV bees with robust gut communities similar in size and composition to those of normal bees sampled from hives (19, 20); however, we cannot entirely rule out effects of other components of the homogenized guts on the treatment bees. Bees were immobilized at 4 °C, and the whole-body wet weight was measured with an electric balance. The expression levels of genes encoding ILP, InR, and Vg were determined by quantitative PCR from RNA extracted from the heads or abdomens of GF and CV bees obtained as described above. Primers used in this study are listed in Table S4. The responsiveness of individual bees to sucrose was assessed by presenting sucrose solutions to the antennae. Examples of response or lack of response are shown in Movie S1. SCFA concentrations within different gut compartments and hemolymph were measured by HPLC. The gut O2 concentrations, pH, and redox potential were measured using microsensors connected to a four-channel amplifier (Unisense). Metabolomic profiles were determined from extracted gut compartments at the University of California, Davis using GC-MS as described by Fiehn and Kind (55).

Table S4.

Primers used for quantitative PCR analyses

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Target | Accession no.* | Ref. |

| AmILP-1F | CGATAGTCCTGGTCGGTTTG | Insulin-like peptide 1 | XM_016913804 | de Azevedo and Hartfelder (79) |

| AmILP-1R | CAAGCTGAGCATAGCTGCAC | |||

| AmILP-2F | TTCCAGAAATGGAGATGGATG | Insulin-like peptide 2 | NM_001177903 | de Azevedo and Hartfelder (79) |

| AmILP-2R | TAGGAGCGCAACTCCTCTGT | |||

| AmInR-1F | GGATCTGGTGTGGGACAGTT | Insulin-like receptor 1 | XM_394771 | de Azevedo and Hartfelder (79) |

| AmInR-1R | ATCCCCACGTCGAGTATCTG | |||

| AmInR-2F | GGGAAGAACATCGTGAAGGA | Insulin-like receptor 2 | NM_001246667 | de Azevedo and Hartfelder (79) |

| AmInR-2R | CATCACGAGCAGCGTGTACT | |||

| Vg-F | GTTGGAGAGCAACATGCAGA | Vitellogenin | AJ517411 | Wang et al. (80) |

| Vg-R | TCGATCCATTCCTTGATGGT | |||

| Rp49-F | CGTCATATGTTGCCAACTGGT | Ribosomal protein 49 | AF441189 | de Azevedo and Hartfelder (79) |

| Rp49-R | TTGAGCACGTTCAACAATGG |

Accession numbers are from GenBank nucleotide sequence database.

SI Materials and Methods

Generation of Germ-Free and Conventional Bees.

GF and CV bees were obtained using the protocol described by Powell et al. (19). In brief, late-stage pupae were removed manually from the brood frames of four different hives collected in Austin, TX, and were placed in sterile plastic bins. The pupae were allowed to emerge in a growth chamber at 35 °C. Ten to twenty newly emerged individuals were kept in an axenic cup-shaped hoarding cage with a removable base and ventilation holes (56) and were fed with sterilized sucrose syrup (0.5 M) and beebread. Beebread was sterilized via gamma irradiation (30 kGy). Batch sterilizations were verified by plating suspensions on LB plates and incubating them at 37 °C overnight. The CV bees were obtained by feeding emerged bees with homogenates of freshly dissected hindguts of nurse bees from their hives of origin, in addition to their food. Each bee was immobilized at 4 °C, and the whole-body wet weight of each bee was measured with an electric balance sensitive to 0.001 g. Guts of 10–15 GF or CV bees were dissected into individual compartments using fine-tipped forceps and then were weighed.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR.

Each dissected whole head or whole abdomen was homogenized with a plastic pestle, and total RNA was extracted from individual samples using the Quick-RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research). cDNA then was synthesized from 1 ng of each RNA sample using the Verso cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific) with provided random hexamer primers. Quantitative PCR was performed using the iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on the ViiA 7 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) in a standard 96-well block (20-µL reactions; 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing/extension and plate read at 60 °C for 60 s). The primers are listed in Table S4. The gene encoding honey bee ribosomal protein 49 served as a reference (32), and relative expression was analyzed using the 2–∆∆CT method (57). Three technical replicates for each sample were performed on the same plate. RNA samples without reverse transcription served as negative controls.

Transcriptome of Hindgut Epithelium.

Three biological replicates per treatment, representing individual bees from unique cup cages (i.e., sampled bees had not come into contact with one another since they were separated into treatment groups) were included in the transcriptome analysis. Total RNA was extracted from dissected hindguts (ileum together with rectum) of GF and CV bees as described by Jorth et al. (58). Briefly, individual hindguts were transferred to bead-beating tubes containing 1 mL of RNA-Bee (Amsbio). Samples were subjected to three iterations of 1 min of bead-beating and 1 min on ice. Lysed solutions were transferred to new 1.5-mL tubes, and 200 µL of chloroform was added. This mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube for overnight precipitation with 500 µL isopropanol and 2 µL linear acrylamide at −80 °C. RNA pellets were washed twice with ice-cold 75% ethanol and were dissolved in 22 µL RNase-free water. Ribosomal RNA was depleted using the Ribo-Zero Gold rRNA Removal Kit (Epidemiology). Preparation of stranded Illumina libraries and single-end 50-bp sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 sequencing system were conducted at the University of Texas at Austin Genomic Sequencing and Analysis Facility.

To quantify gene expression, RNA-sequencing reads were trimmed with FLEXBAR (59) to remove Illumina adaptor sequences and were mapped to the A. mellifera genome from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (60) (version Amel_4.5 assembly; GenBank accession number GCA_000002195) using TopHat2 (61). However, we found that sequences in the Amel_4.5 assembly have 100% nucleotide identity to bacterial sequences, indicating that they are misannotated as bee genes. Thus, additional steps were taken to identify and remove bacterial genes from our analysis. We searched for potential bacterial sequences by comparing nucleotide sequences of all 13,592 genes extracted from the general features format (GFF) file of Amel_4.5 assembly against the bacterial genomes in the NCBI Representative Genomes database using BLASTN with cutoffs of ≤0.0001 e-value, ≥70% identity, and ≥25% coverage. Additional screening was performed by comparing the nucleotide sequences from the GFF file to the Reference Proteins database from NCBI using BLASTX. In total, we identified 227 putative bacterial genes, and these sequences were removed from the downstream analysis. To analyze differential expression of the bee genes in the CV and GF hindgut epithelium, RNA-sequencing reads were mapped to the modified GFF file of Amel_4.5 assembly. Reads mapping to each gene were counted using the Python package HTSeq (62). Differential expression was determined using DESeq2 (63) with a false-discovery rate cutoff of 0.05.

Responsiveness to Sucrose.

Seven-day-old GF and CV bees generated as described above were used to measure the response to sucrose. Before the test, bees were starved for 18 h by removing sugar syrup and bee bread from the cup cage. Bees then were immobilized at 4 °C for about 15 min and were mounted to modified 1.5-mL centrifuge tubes using Parafilm M (Bemis). Individual responsiveness was measured by presenting a series of sucrose concentration solutions (0, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 30%; wt/vol) to the antennae of bees (37). When a bee’s antenna is stimulated with a sucrose solution of sufficient concentration, the bee reflexively extends its proboscis (Movie S1). The number of bees with initial proboscis extension at each concentration was recorded.

Detection of Metabolites in Vivo and in Vitro.

SCFA concentrations within different gut compartments and hemolymph were measured by HPLC. Ten to twenty microliters of each gut compartment were homogenized in 50 μL water and were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was filtered with 0.22-µm microcentrifuge tube filters (Corning) for 10 min at 10,000 × g, and the filtrate was acidified with H2SO4 (final concentration 10 mM). Hemolymph (2–8 μL) was collected from an incision in the cuticle at the base of the head of each bee using a graduated microcapillary tube (64). Pooled hemolymph (20–30 µL) was also filtered and acidified as described above. SCFAs were quantified by ion-exclusion chromatography using an HPLC system with MetaCarb 87H column (300 × 6.5 mm; Varian) at 55 °C using a mobile phase of 5 mM H2SO4 (0.7 mL/min) and a UV detector (Varian). Peak identity was verified using external standards (1,000 µg/mL) (Inorganic Ventures). The concentrations of glucose, fructose, and acetate were identified using respective enzymatic assay kits (Megazyme). The absence of ethanol was confirmed using the enzymatic assay kit (Abnova).

G. apicola strains were grown in BYZ medium (18) amended with 5 mM each of glucose and fructose. Lactobacillus sp. strains were grown in a defined medium composed of (per liter) 20 g glucose, 2 g peptone, 1 g yeast extract, 1 g polysorbate 80, 0.4 g NH4Cl, 0.2 g MgSO40.7H2O, 0.07 g MnCl20.4H2O, 2 g KH2PO4, 0.4 g l-cysteine hydrochloride, 0.1 g pyridoxine hydrochloride, 0.5 g pantothenic acid, 0.1 g inositol, 0.01 g aminobenzoic acid, and 0.02 g adenine (65). To detect SCFAs, sodium acetate was omitted from the original medium. All media were prepared under N2 and contained DTT (1 mM) as a reducing agent and resazurin (0.4 mg/L) as a redox indicator (66). Growth experiments were conducted in 16-mL anaerobic Hungate culture tubes (Chemglass Life Sciences) with 5 mL of medium at 37 °C. The influence of oxygen on the fermentation products was tested in nonreduced medium by the addition of different amounts of sterile ambient air to the headspace of cultures. Metabolites in the supernatant of fully grown (2- to 3-d-old) cultures were quantitated by HPLC as described above.

Microsensor Measurements.

Oxygen concentrations, pH, and redox potential within the bee gut were measured using microsensors with tip diameters of 50 μm connected to a four-channel amplifier (Unisense). All sensors were calibrated as described by Bauer et al. (67) The dissected guts were placed onto a bottom layer of 2% (wt/vol) agarose and were embedded in insect Ringer’s solution (68) (1 L containing 10.4 g NaCl, 0.32 g KCl, 0.48 g CaCl2, and 0.32 g NaHCO3; pH 6.8) solidified with 0.5% (wt/vol) agarose. The measurements were performed in glass microchambers using a setup as described by Brune et al. (69).

Oxygen Consumptions by S. alvi.

S. alvi strain wkB2 was grown in BYZ medium containing 10 mM sodium acetate. Fully grown cells were harvested by centrifugation (7,200 × g, 15 min, 4 °C), washed twice in insect Ringer’s solution (68), and resuspended in 5 mL of the same solution that was aerated by vigorous vortexing for 10 min in a 28-mL glass test tube (18 × 150 mm) to obtain 20× the initial cell density. The headspace was gassed with N2 and then quickly sealed with dental wax. The oxygen concentrations in the cell suspensions were measured with the microelectrode as described above. The oxygen uptake rate was measured before and after the addition of substrates (10 mM sodium acetate, sodium lactate, or D-glucose).

Transmission Electron Microscopy.

Electron microscopy was done as described by Engel et al. (70). Briefly, dissected guts were fixed in sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M; pH 7.4) containing 2.5% gluteraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde for 1 h. Then the samples were rinsed three times in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and were postfixed with osmium tetroxide (1%) for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were washed three times with distilled water, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, and incubated in propylene oxide-Epon (1:1, vol:vol) for 1 h. Samples were transferred into fresh Epon in molds and cured in the oven overnight at 60 °C. Ultrathin-sections were stained with uranyl acetate and examined with a Zeiss EM900 transmission electron microscope.

Metabolomics.

Ten to fifteen gut compartments (200 mg for midgut, 10 mg for ileum, 300 mg for rectum) and 50 μL of the hemolymph of GF and CV bees were quickly sampled and stored at −80 °C. Six biological replicates from different cup cages of each group were shipped on dry ice to the West Coast Metabolomics Center at the University of California, Davis Genome Center, Davis, CA, for metabolomics analysis. Metabolites were extracted as described by Fiehn and Kind (55); in short, samples were supplemented with 1 mL extraction solvent (acetonitrile:isopropanol:H2O, 3:3:2; vol/vol/vol) and were homogenized using a Geno/Grinder (SPEX SamplePrep) for 45 s. After centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 5 min), supernatants were evaporated in the Centrivap cold trap concentrator (Labconco) until completely dry. Pellets were washed in 500 μL of 50% acetonitrile (vol/vol) and were dried again. The extracts were supplemented with 2 μL internal retention index markers and derivatized.

Metabolite profiles were analyzed using GC–MS with a nontargeted MS approach. [See Fiehn et al. (71) for details for injector and oven temperatures, column specifications, ionization, and MS.] Raw data files were preprocessed directly after data acquisition using ChromaTOF version 2.32 (Leco). Data were further processed by a filtering algorithm implemented in the metabolomics BinBase database (72); metabolites were identified using retention index and mass spectrum and were matched against the FiehnLib libraries (73). Metabolomics data analysis was then performed using MetaboAnalyst 3.0 (74). Data (Dataset S3) were filtered using interquartile range approach and were normalized with the options of normalization by the sum, logarithm transformation, and auto scaling to reduce systematic bias during sample collection (75). The fold change (CV/GF) was calculated based on the normalized data from each gut compartment and hemolymph, and the significance were calculated using the t test. The dataset then was subjected to a PCA. We defined 95% confidence interval ellipses (based on the SD for each PC) (76) to support the significance of each CV and GF cluster visually. For the heatmap plot, the built-in heatmap and clustering functions of MetaboAnalyst were used. As default, MetaboAnalyst employs Ward's minimum variance clustering in combination with the Pearson distance measure.

Metabolic pathway analysis was based on the metabolites of hemolymph using the Drosophila melanogaster pathway library from Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database (KEGG GENOME No. T00030) to identify the bee host pathways altered by the presence of gut microbiota. This analysis used the R/Bioconductor package limma (77). Multiple linear modeling was carried to fit each annotated compound by generalized least squares. Treatments (GF or CV) were coded into the design matrix to construct contrasts for the metabolites of hemolymph (CV–GF). Qualifying compounds were subjected to a pathway analysis using the module from MetaboAnalyst (version 3.0) and all annotated compounds as the reference metabolome. Overrepresentation was analyzed by a hypergeometric test and taking pathway topology into account (Relative-betweeness Centrality). Significance was declared when the false discovery rate (78) was smaller than 0.1.

Statistical Analysis.

Comparisons of the body weight, gut compartment weight, and the gene expressions of GF and CV bees were made by Mann–Whitney u test. Comparisons of multiple samples were made by an analysis of variances followed by Tamhane’s T2 post hoc test. Comparison of the distribution of sucrose response thresholds was made using a χ2 test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Philipp Engel (University of Lausanne) for contributing the transmission electron microscope image and for comments on the paper; Juan Barraza and Marvin Whiteley (University of Texas at Austin) for assistance with HPLC analyses; and Kim Hammond for beekeeping assistance. This work was supported by NIH Grant 1R01-GM108477-01 (to N.A.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1701819114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gallai N, Salles JM, Settele J, Vaissiere BE. Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecol Econ. 2009;68:810–821. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollinator Health Task Force . Pollinator Partnership Action Plan. The White House; Washington, DC: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seitz N, et al. A national survey of managed honey bee 2014-2015 annual colony losses in the USA. J Apic Res. 2016;54:292–304. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engel P, et al. The bee microbiome: Impact on bee health and model for evolution and ecology of host-microbe interactions. mBio. 2016;7:e02164-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02164-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raymann K, Shaffer Z, Moran NA. Antibiotic exposure perturbs the gut microbiota and elevates mortality in honeybees. PLoS Biol. 2017;15:e2001861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwong WK, Moran NA. Gut microbial communities of social bees. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:374–384. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwong WK, et al. Dynamic microbiome evolution in social bees. Sci Adv. 2016;3:e1600513. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moeller AH, et al. Cospeciation of gut microbiota with hominids. Science. 2016;353:380–382. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwong WK, Moran NA. Cultivation and characterization of the gut symbionts of honey bees and bumble bees: Description of Snodgrassella alvi gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the family Neisseriaceae of the Betaproteobacteria, and Gilliamella apicola gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of Orbaceae fam. nov., Orbales ord. nov., a sister taxon to the order ‘Enterobacteriales’ of the Gammaproteobacteria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:2008–2018. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.044875-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinson VG, Moy J, Moran NA. Establishment of characteristic gut bacteria during development of the honeybee worker. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:2830–2840. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07810-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flint HJ, Scott KP, Louis P, Duncan SH. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:577–589. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Naylor CP, Macfarlane GT. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut. 1987;28:1221–1227. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.10.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donohoe DR, et al. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon. Cell Metab. 2011;13:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odelson DA, Breznak JA. Volatile fatty acid production by the hindgut microbiota of xylophagous termites. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45:1602–1613. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.5.1602-1613.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeitouni NE, Chotikatum S, von Köckritz-Blickwede M, Naim HY. The impact of hypoxia on intestinal epithelial cell functions: Consequences for invasion by bacterial pathogens. Mol Cell Pediatr. 2016;3:14. doi: 10.1186/s40348-016-0041-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engel P, Martinson VG, Moran NA. Functional diversity within the simple gut microbiota of the honey bee. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202970109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng H, et al. Metabolism of toxic sugars by strains of the bee gut symbiont Gilliamella apicola. mBio. 2016;7:e01326-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01326-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell JE, Martinson VG, Urban-Mead K, Moran NA. Routes of acquisition of the gut microbiota of the honey bee Apis mellifera. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:7378–7387. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01861-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwong WK, Engel P, Koch H, Moran NA. Genomics and host specialization of honey bee and bumble bee gut symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:11509–11514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405838111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarzer M, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum strain maintains growth of infant mice during chronic undernutrition. Science. 2016;351:854–857. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanton LV, et al. Gut bacteria that prevent growth impairments transmitted by microbiota from malnourished children. Science. 2016;351:830–857. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin SC, et al. Drosophila microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science. 2011;334:670–674. doi: 10.1126/science.1212782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrison JM. Caste-specific changes in honeybee flight capacity. Physiol Zool. 1986;59:175–187. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toth AL, Robinson GE. Worker nutrition and division of labour in honeybees. Anim Behav. 2005;69:427–435. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ihle KE, Baker NA, Amdam GV. Insulin-like peptide response to nutritional input in honey bee workers. J Insect Physiol. 2014;69:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2014.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Q, Brown MR. Signaling and function of insulin-like peptides in insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 2006;51:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corona M, et al. Vitellogenin, juvenile hormone, insulin signaling, and queen honey bee longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7128–7133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701909104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foret S, et al. DNA methylation dynamics, metabolic fluxes, gene splicing, and alternative phenotypes in honey bees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:4968–4973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202392109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wheeler DE, Buck N, Evans JD. Expression of insulin pathway genes during the period of caste determination in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Insect Mol Biol. 2006;15:597–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amdam GV, Fennern E, Havukainen H. Vitellogenin in honey bee behavior and lifespan. In: Galizia CG, Eisenhardt D, Giurfa M, editors. Honeybee Neurobiology and Behavior: A Tribute to Randolf Menzel. Springer Netherlands; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2012. pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ament SA, Corona M, Pollock HS, Robinson GE. Insulin signaling is involved in the regulation of worker division of labor in honey bee colonies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4226–4231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800630105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ament SA, et al. Mechanisms of stable lipid loss in a social insect. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:3808–3821. doi: 10.1242/jeb.060244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nilsen KA, et al. Insulin-like peptide genes in honey bee fat body respond differently to manipulation of social behavioral physiology. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:1488–1497. doi: 10.1242/jeb.050393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schonbaum CP, Lee S, Mahowald AP. The Drosophila yolkless gene encodes a vitellogenin receptor belonging to the low density lipoprotein receptor superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1485–1489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mott CM, Breed MD. Insulin modifies honeybee worker behavior. Insects. 2012;3:1084–1092. doi: 10.3390/insects3041084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheiner R, Page RE, Erber J. Sucrose responsiveness and behavioral plasticity in honey bees (Apis mellifera) Apidologie (Celle) 2004;35:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyun S. Body size regulation and insulin-like growth factor signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:2351–2365. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1313-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Espey MG. Role of oxygen gradients in shaping redox relationships between the human intestine and its microbiota. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;55:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brune A. Termite guts: The world’s smallest bioreactors. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan MT, et al. The gut anaerobe Faecalibacterium prausnitzii uses an extracellular electron shuttle to grow at oxic-anoxic interphases. ISME J. 2012;6:1578–1585. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wertz JT, Breznak JA. Physiological ecology of Stenoxybacter acetivorans, an obligate microaerophile in termite guts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:6829–6841. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00787-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powell JE, Leonard SP, Kwong WK, Engel P, Moran NA. Genome-wide screen identifies host colonization determinants in a bacterial gut symbiont. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:13887–13892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610856113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Million M, et al. Increased gut redox and depletion of anaerobic and methanogenic prokaryotes in severe acute malnutrition. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26051. doi: 10.1038/srep26051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45.den Besten G, et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2325–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee WJ, Hase K. Gut microbiota-generated metabolites in animal health and disease. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:416–424. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukuda S, et al. Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature. 2011;469:543–547. doi: 10.1038/nature09646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vital M, Howe AC, Tiedje JM. Revealing the bacterial butyrate synthesis pathways by analyzing (meta)genomic data. mBio. 2014;5:e00889. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00889-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donohoe DR, Wali A, Brylawski BP, Bultman SJ. Microbial regulation of glucose metabolism and cell-cycle progression in mammalian colonocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tegtmeier D, Thompson CL, Schauer C, Brune A. Oxygen affects gut bacterial colonization and metabolic activities in a gnotobiotic cockroach model. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;82:1080–1089. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03130-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ellegaard KM, et al. Extensive intra-phylotype diversity in lactobacilli and bifidobacteria from the honeybee gut. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:284. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1476-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tholen A, Schink B, Brune A. The gut microflora of Reticulitermes flavipes, its relation to oxygen, and evidence for oxygen-dependent acetogenesis by the most abundant Enterococcus sp. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;24:137–149. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Donia MS, Fischbach MA. Human microbiota. Small molecules from the human microbiota. Science. 2015;349:1254766. doi: 10.1126/science.1254766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Christofi FL. Unlocking mysteries of gut sensory transmission: Is adenosine the key? News Physiol Sci. 2001;16:201–207. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.5.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fiehn O, Kind T. Metabolite profiling in blood plasma. In: Weckwerth W, editor. Metabolomics: Methods and Protocols. Humana; Totowa, NJ: 2006. pp. 3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams GR, et al. Standard methods for maintaining adult Apis mellifera in cages under in vitro laboratory conditions. J Apic Res. 2013;52:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jorth P, et al. Metatranscriptomics of the human oral microbiome during health and disease. mBio. 2014;5:e01012-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01012-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dodt M, Roehr JT, Ahmed R, Dieterich C. FLEXBAR—Flexible barcode and adapter processing for next-generation sequencing platforms. Biology (Basel) 2012;1:895–905. doi: 10.3390/biology1030895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elsik CG, et al. Community annotation: Procedures, protocols, and supporting tools. Genome Res. 2006;16:1329–1333. doi: 10.1101/gr.5580606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim D, et al. TopHat2: Accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hartfelder K, et al. Standard methods for physiology and biochemistry research in Apis mellifera. J Apic Res. 2013;52:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Menon R, Shields M, Duong T, Sturino JM. Development of a carbohydrate-supplemented semidefined medium for the semiselective cultivation of Lactobacillus spp. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2013;57:249–257. doi: 10.1111/lam.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zheng H, Dietrich C, Radek R, Brune A. Endomicrobium proavitum, the first isolate of Endomicrobia class. nov. (phylum Elusimicrobia)–an ultramicrobacterium with an unusual cell cycle that fixes nitrogen with a Group IV nitrogenase. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:191–204. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bauer E, et al. Physicochemical conditions, metabolites and community structure of the bacterial microbiota in the gut of wood-feeding cockroaches (Blaberidae: Panesthiinae) FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2015;91:1–14. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiu028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Federle W, Brainerd EL, McMahon TA, Hölldobler B. Biomechanics of the movable pretarsal adhesive organ in ants and bees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6215–6220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111139298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brune A, Emerson D, Breznak JA. The termite gut microflora as an oxygen sink: Microelectrode determination of oxygen and pH gradients in guts of lower and higher termites. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2681–2687. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2681-2687.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Engel P, Bartlett KD, Moran NA. The bacterium Frischella perrara causes scab formation in the gut of its honeybee host. mBio. 2015;6:e00193-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00193-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fiehn O, et al. Quality control for plant metabolomics: Reporting MSI-compliant studies. Plant J. 2008;53:691–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fiehn O, Wohlgemuth G, Scholz M. Setup and annotation of metabolomic experiments by integrating biological and mass spectrometric metadata. In: Ludäscher B, Raschid L, editors. Data Integration in the Life Sciences. vol 3615. Springer GmbH; Berlin: 2005. pp. 224–239. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kind T, et al. FiehnLib: Mass spectral and retention index libraries for metabolomics based on quadrupole and time-of-flight gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:10038–10048. doi: 10.1021/ac9019522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xia J, Sinelnikov IV, Han B, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst 3.0–making metabolomics more meaningful. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W251-7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xia J, Wishart DS. Web-based inference of biological patterns, functions and pathways from metabolomic data using MetaboAnalyst. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:743–760. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xia J, Wishart DS. Using MetaboAnalyst 3.0 for comprehensive metabolomics data analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2016;5:14.10.11–14.10.91. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ritchie ME, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 79.de Azevedo SV, Hartfelder K. The insulin signaling pathway in honey bee (Apis mellifera) caste development—Differential expression of insulin-like peptides and insulin receptors in queen and worker larvae. J Insect Physiol. 2008;54(6):1064–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang Y, Brent CS, Fennern E, Amdam GV. Gustatory perception and fat body energy metabolism are jointly affected by vitellogenin and juvenile hormone in honey bees. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(6):e1002779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.