Abstract

Background

Establishing and managing a board certification system is a common concern for many countries. In Japan, the board certification system is under revision. The purpose of this study was to describe present status of internal medicine specialist board certification, to identify factors associated with maintenance of board certification and to investigate changes in area of practice when physicians move from hospital to clinic practice.

Methods

We analyzed 2010 and 2012 data from the Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists. We conducted logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with the maintenance of board certification between 2010 and 2012. We also analyzed data on career transition from hospitals to clinics for hospital physicians with board certification.

Results

It was common for physicians seeking board certification to do so in their early career. The odds of maintaining board certification were lower in women and those working in locations other than academic hospitals, and higher in physicians with subspecialty practice areas. Among hospital physicians with board certification who moved to clinics between 2010 and 2012, 95.8% remained in internal medicine or its subspecialty areas and 87.7% maintained board certification but changed their practice from a subspecialty area to more general internal medicine.

Conclusion

Revisions of the internal medicine board certification system must consider different physician career pathways including mid-career moves while maintaining certification quality. This will help to secure an adequate number and distribution of specialists. To meet the increasing demand for generalist physicians, it is important to design programs to train specialists in general practice.

Keywords: Board certification, Subspecialty, Maintenance of certification, Career pathway, Internal medicine

Background

Establishing and maintaining a quality assurance system for medical practitioners is a priority in the postgraduate and continuing education systems. The establishment and management of a board certification system is a common concern for many countries.

Different countries have different certification and maintenance systems based on their specific healthcare delivery systems. Common issues are the quality of care [1–3], requirements and conditions of specialty certification, curriculum for board certification, maintenance of certification and demand for specialists [4–11]. A United States study of medical school graduates from the 1997–2000 cohort found that 87.3% had American Board of Medical Specialties certification and argued that board certification was emerging as a de facto requirement for full participation of medical practitioners in the US healthcare system [12].

In Japan, the board certification system has developed and has operated by respective academic societies; it is not directly linked to reimbursement systems and it is not mandatory hospitals and clinics to be staffed by board certified medical practitioners. The number of medical practitioners with board certification has been increasing. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare reported that 56.9% of medical practitioners had one or more board certifications in 2014 [13], a 2.9% increase from 2012 [14]. The Commission on the Reform of the Board Certified System recommended that awareness be raised of the need for standardization that a quality assurance system of board certification be established and that maldistribution of board certified medical practitioners be addressed. It was also recommended that an independent organization for certification of specialists and training programs be established. A two-tier board system for basic and subspecialty board certification has been proposed, with basic certification mandatory before subspecialty board certification. It was also recommended to establish general practice as a basic area of board certification [15].

It was planned that the new system would be implemented from 2017; however, relevant stakeholders have not yet reached agreement and implementation has been postponed. In December 2016, the Japanese Medical Specialty Board released its Guidelines for Board Certification. It requires at least 5 years of training (including 2 years of postgraduate clinical training) after medical practitioner registration and successful completion of the training program for basic board certification. The duration of certification is 5 years, and is renewable if the requirements for maintenance of board certification are met [16].

The internal medicine board certification system was first introduced in 1968 as Fellow/Board Certified Membership of the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine. It required physicians to complete 5 years of training at accredited educational facilities and pass and examination. The system for internal medicine subspecialty board certification followed; there are now 13 subspecialties in internal medicine [17]. In 1994 “board-certified specialists in internal medicine” became known as “certified physicians and board-certified specialists in general internal medicine” [18]. Concurrently with the government commission’s recommendations, the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine revised the quantity of training required to achieve specialist board certification by requiring 3 years of training in internal medicine after 2 years of postgraduate clinical training had been completed, increased from a period of 3 years of training that included 2 years of postgraduate clinical training to become Board Certified Member of the Society.

Analysis of the physician career pathway can inform the design of human resources systems. Japan has an aging population that will require greater availability of family and general medicine. The demand for board certification will also increase. The internal medicine career pathway will change under these circumstances. There have been several studies of the Japanese board certification systems in surgery [19, 20], cerebrovascular surgery [21], anesthesiology [22], head and neck surgery [23], and consultation-liaison psychiatry [24]. In our previous study of surgeons, we found that the odds of women maintaining board certification was lower, even after adjusting for other factors. As the proportion of Japanese physicians is increasing, there is increasing interest in career differences between men and women in internal medicine [20].

The purpose of this study was to investigate the current status of board certification in internal medicine, identify factors associated with the maintenance of board certification, and to analyze change of practice area when internal medicine specialists left hospitals to practice in clinics. Finally, we also aimed to discuss the potential policy implications of our findings.

Methods

To examine the current status and dynamics of board certification in internal medicine, factors associated with maintenance of board certification, and the career transitions of hospital-based specialists, we merged the data of the 2010 and 2012 Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists. The Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists is a national census survey of physicians conducted every 2 years by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. In Japan, all licensed medical practitioners are required to report their working status in the biannual Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists. Although the survey was designed as a census, the estimated reporting rate for the 2000 survey was 90.3% [25]. The survey collects the following self-reported snapshot data about each physician on December 31: sex; date of birth; place of work; type of working facilities; area of practice and board certification status. Survey form is available from the Ministry’s website [26]. We obtained permission from the Ministry to analyze the survey data.

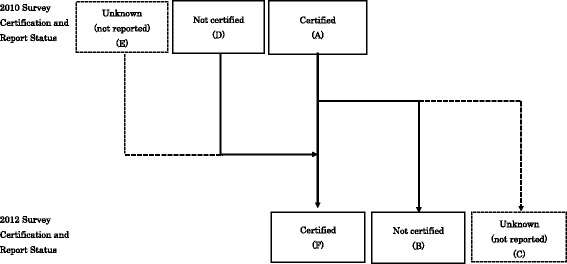

To examine the dynamics of board certification, we analyzed changes in board certification status between 2010 and 2012 survey in nine sub cohorts based on their year of registration (defined as those who registered as medical practitioners in or before 1972, then in seven 5-year cohorts from 1973 to 1977 to 2008–2012)(Fig. 1). To examine factors associated with maintenance of board certification, data for the 37,219 physicians who reported that they held board certification in internal medicine were analyzed. We conducted logistic regression analysis to identify factors such as sex, years of experience (0–9, 10–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49 and ≥50), workplace (academic hospital, other hospital, clinics or others), type of municipality (city, town or village), and area of practice (internal medicine, subspecialty area in internal medicine) associated with the odds of maintenance of certification. These factors were assessed using 2010 data. Maintenance of board certification was defined as certification in at least one area of internal medicine in both 2010 and 2012 (these could be different areas). Then, status of career transition of board-certified physicians from hospital in 2010 (n = 24,788), practice area distribution and board certification status for physicians who moved from hospitals to clinics (n = 1063) were also analyzed.

Fig. 1.

The change in certification status between 2010 and 2012 by physician registration year. Physicians who reported they were board certified in 2010 (A) either kept certification (F), lost certification (B) or their status became unknown (not reported) (C) in 2012. In addition to physicians certified both in 2010 and 2012, some were not certified in 2010 but certified in 2012 (D) and some whose certification status was known (not reported) in 2010 appeared to be certified in 2012 (E)

All physicians would report their area of practice, and those who were board certified would report their area of certification; however, some may have been practicing in areas in which they were not board certified. We defined internal medicine physicians as those reported their main area of practice as internal medicine, respiratory medicine, cardiology, gastroenterological medicine, nephrology, neurology, diabetes and metabolism, hematology, allergy, rheumatology and/or infectious diseases. Main areas of practice other than internal medicine were classed as subspecialty areas of practice in internal medicine. Thirteen internal medicine subspecialty as for the area of board certification were defined with reference to the internal medicine specialty training standards of the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine [27]: general internal medicine, respiratory medicine, cardiology, gastroenterological medicine, hepatology, nephrology, neurology, diabetes, metabolism, hematology, allergy, rheumatology, infectious diseases, and gerontology.

A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics (version 20.0 J, SPSS IBM Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

The majority of respondents in 2010 (59.4%, 61,877 out of 104,193) and 2012 (57.1%, 61,177 out of 107,105) chose internal medicine as their main area of practice, followed by gastroenterological medicine and cardiology. 37.5%, 39,043 out of 104,193 in 2010 and 39.3%, 42,060 out of 107,105 in 2012 internist were board certified in one area or more. Among physicians who reported their area of practice in internal medicine, 84.4% (87,969 out of 104,193) and 83.7%(89, 611 out of 107,105) were men in 2010 and 2012, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects

| 2010 report | 2012 report | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 104,193) | (n = 107,105) | ||||

| Sex (n, %) | |||||

| Male | 87,969 | 84.4 | 89,611 | 83.7 | |

| Female | 16,224 | 15.6 | 17,494 | 16.3 | |

| Years of experience (mean, standard deviation) | |||||

| 24.2 | 14.7 | 24.5 | 14.6 | ||

| Type of municipality (n, %) | |||||

| Special wards | 36,303 | 34.8 | 38,823 | 36.2 | |

| Cities | 60,871 | 58.4 | 61,520 | 57.4 | |

| Towns and villages | 7,019 | 6.7 | 6,762 | 6.3 | |

| Type of medical institution (n, %) | |||||

| Academic hospitals | 13,717 | 13.2 | 14,480 | 13.5 | |

| Other hospitals | 43,967 | 42.2 | 45,948 | 42.9 | |

| Clinics and others | 46,509 | 44.6 | 46,677 | 43.6 | |

| Main area of practice (n, %) | |||||

| Internal medicine | 61,877 | 59.4 | 61,177 | 57.1 | |

| Gastroenterological medicine | 12,188 | 11.7 | 13,080 | 12.2 | |

| Cardiology | 10,829 | 10.4 | 11,541 | 10.8 | |

| Respiratory medicine | 4944 | 4.7 | 5337 | 5.0 | |

| Neurology | 4094 | 3.9 | 4361 | 4.1 | |

| Diabetes and metabolism | 3488 | 3.3 | 3966 | 3.7 | |

| Nephrology | 3085 | 3.0 | 3492 | 3.3 | |

| Hematology | 2118 | 2.0 | 2353 | 2.2 | |

| Rheumatology | 1058 | 1.0 | 1228 | 1.1 | |

| Infectious diseases | 303 | 0.3 | 367 | 0.3 | |

| Allergy | 209 | 0.2 | 203 | 0.2 | |

| Board-certified physicians (n, %) | |||||

| General internal medicine | 13,896 | 13.3 | 13,607 | 12.7 | |

| Gerontology | 936 | 0.9 | 975 | 0.9 | |

| Gastroenterological medicine | 11,283 | 10.8 | 12,090 | 11.3 | |

| Hepatology | 3097 | 3.0 | 3583 | 3.3 | |

| Cardiology | 9150 | 8.8 | 9884 | 9.2 | |

| Respiratory medicine | 3602 | 3.5 | 4027 | 3.8 | |

| Neurology | 3285 | 3.2 | 3555 | 3.3 | |

| Diabetes | 3374 | 3.2 | 3763 | 3.5 | |

| Metabolism | 1293 | 1.2 | 1399 | 1.3 | |

| Nephrology | 2347 | 2.3 | 2622 | 2.4 | |

| Hematology | 1876 | 1.8 | 2055 | 1.9 | |

| Rheumatology | 1407 | 1.4 | 1618 | 1.5 | |

| Infectious diseases | 615 | 0.6 | 696 | 0.6 | |

| Allergy | 1196 | 1.1 | 1301 | 1.2 | |

| Number of board certifications (n, %) | |||||

| None | 65,150 | 62.5 | 65,045 | 60.7 | |

| 1 | 24,149 | 23.2 | 26,518 | 24.8 | |

| 2 | 11,902 | 11.4 | 12,381 | 11.6 | |

| ≥ 3 | 2992 | 2.8 | 3161 | 2.9 | |

Dynamics of board certification status

Physicians seeking board certification tended to do so earlier in their early career (Table 2). Logistic regression showed that the odds of maintaining board certification were lower in women and those working at locations other than academic hospitals, and higher in those who practiced a subspecialty of internal medicine (Table 3).

Table 2.

Changes in board certification status between 2010 and 2012

| Year of registration as physician | Certified as of 2010 survey | Lost certification | Not reported in 2012 survey | Obtained certification | Not reported in 2010 survey | Certified as of 2012 survey |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (D) | (E) | (F) | |

| 2012–2008 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2007–2003 | 890 | 97 | 75 | 2000 | 163 | 2881 |

| 2002–1998 | 5183 | 419 | 324 | 1452 | 388 | 6280 |

| 1997–1993 | 6579 | 512 | 237 | 860 | 267 | 6957 |

| 1992–1988 | 7048 | 499 | 228 | 655 | 234 | 7210 |

| 1987–1983 | 6325 | 523 | 183 | 589 | 151 | 6359 |

| 1982–1978 | 5539 | 509 | 165 | 536 | 138 | 5539 |

| 1977–1973 | 3176 | 329 | 122 | 331 | 92 | 3148 |

| 1972 or before | 4228 | 955 | 495 | 684 | 189 | 3651 |

| Total | 38,968 | 3843 | 1829 | 7107 | 1622 | 42,025 |

Table 3.

Factors associated with holding board certification in internal medicine

| Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| Female | 0.87 | 0.79 | – | 0.97 | 0.01 | |

| Years since registration as physician | ||||||

| 0–9 | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| 10–19 | 1.53 | 1.32 | – | 1.77 | <0.001 | |

| 20–29 | 1.69 | 1.46 | – | 1.96 | <0.001 | |

| 30–39 | 1.28 | 1.10 | – | 1.50 | <0.001 | |

| 40–49 | 0.54 | 0.45 | – | 0.64 | <0.001 | |

| ≥ 50 | 0.22 | 0.18 | – | 0.28 | <0.001 | |

| Type of municipality | ||||||

| City | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| Town or village | 0.93 | 0.80 | – | 1.08 | 0.31 | |

| Type of institution | ||||||

| Academic hospital | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| Other hospital | 0.75 | 0.67 | – | 0.84 | <0.001 | |

| Clinics and others | 0.65 | 0.57 | – | 0.74 | <0.001 | |

| Main area of practice | ||||||

| Internal medicine | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| Subspecialty area | 1.51 | 1.40 | – | 1.64 | <0.001 | |

Career transition from hospitals to clinics and practice area

Among hospital physicians with board certification, 4.3% moved to clinics between 2010 and 2012 (Table 4); 87.7% maintained board certification but changed from a subspecialty area to more general internal medicine (Table 5), but 95.8% of physicians who moved to a clinic maintained their practice within internal medicine or one or more of its subspecialty areas (Table 6).

Table 4.

Status of career transition of board-certified physicians from hospital to clinic

| Years since registration as physician | Status in 2010 | Status in 2012 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital physician with board certification | Moved to clinic (n) | Moved to clinic (%) | Holding board certification (n) | Holding board certification (%) | |

| 0–9 | 2712 | 115 | 4.2 | 97 | 84.3 |

| 10–19 | 9953 | 501 | 5.0 | 447 | 89.2 |

| 20–29 | 7551 | 266 | 3.5 | 242 | 91.0 |

| 30–39 | 3439 | 121 | 3.5 | 99 | 81.8 |

| 40–49 | 939 | 50 | 5.3 | 40 | 80.0 |

| ≥50 | 194 | 10 | 5.2 | 7 | 70.0 |

| Total | 24,788 | 1063 | 4.3 | 932 | 87.7 |

Table 5.

Board certification status for physicians who moved from hospitals to clinics between 2010 and 2012

| Board certification status | 2010 in hospitals | 2012 in clinics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Area of board certification | |||||

| General internal medicine | 371 | 34.9 | 326 | 30.7 | |

| Gerontology | 27 | 2.5 | 21 | 2.0 | |

| Gastroenterological medicine | 302 | 28.4 | 270 | 25.4 | |

| Hepatology | 80 | 7.5 | 90 | 8.5 | |

| Cardiology | 242 | 22.8 | 223 | 21.0 | |

| Respiratory medicine | 116 | 10.9 | 103 | 9.7 | |

| Neurology | 70 | 6.6 | 60 | 5.6 | |

| Diabetes | 126 | 11.9 | 124 | 11.7 | |

| Metabolism | 29 | 2.7 | 32 | 3.0 | |

| Nephrology | 87 | 8.2 | 79 | 7.4 | |

| Hematology | 36 | 3.4 | 30 | 2.8 | |

| Rheumatology | 41 | 3.9 | 37 | 3.5 | |

| Infectious diseases | 15 | 1.4 | 11 | 1.0 | |

| Allergy | 28 | 2.6 | 28 | 2.6 | |

| Number of board certifications | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 131 | 12.3 | |

| 1 | 642 | 60.4 | 511 | 48.1 | |

| 2 | 340 | 32.0 | 347 | 32.6 | |

| ≥ 3 | 81 | 7.6 | 74 | 7.0 | |

Table 6.

Area of practice and board certification status of physicians who moved from hospitals to clinics between 2010 and 2012 (n = 1, 063)

| Main area of practice | Internal medicine | Subspecialty in internal medicine | Other area of practice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As of 2010 (Hospital) | Area of practice (%) | 334 (31.4) | 729 (68.6) | Not applicable |

| Number board certified (%) | 334 (100) | 729 (100) | Not applicable | |

| As of 2012 (Clinics) | Area of practice (%) | 611 (57.5) | 407 (38.3) | 45 (4.2) |

| Number board certified (%) | 525 (85.9) | 377 (92.6) | 30 (66.7) | |

Discussion

We found that women were less likely to maintain board certification in internal medicine or one of its subspecialty areas after adjusting for possible confounding factors, results that are consistent with our previous study of women in surgery [20]. It appears that women have difficulty maintaining board certification status in internal medicine and surgery. It is therefore critical that obstacles for female physicians must be overcome so as to meet the increasing demand for internists and specialists, for example by creating supportive working environment).

We also found that internal medicine specialists who move to clinics generally stay within internal medicine and maintain board certification, but often change to more general practice. This career pathway is different from that of surgeons, who may change their area of practice from surgery to internal medicine [20]. Japan has well-equipped advanced medical facilities [28], but the number of open hospitals is still limited (918 hospitals out of 8481 facilities as of 2014 [29]). Because surgeons need medical facilities that allow them to perform operations, many who have moved from hospitals to clinics may cease their surgical practice, which likely explains why surgeons who move from hospitals to clinics are less likely to maintain board certification than their internal medicine counterparts. However, this does not mean that board certification requirements differ between types of medical facility. As the role and function of board certification evolves and more physicians seek board certification, the roles of hospitals, clinics and the reimbursement system will also likely to change.

Our results reflect the fact that internists treat large numbers of patients with a wide range of disorders and provide primary medical care and disease management as necessary. In Japan, general practice/family medicine had not been an official category of area of practice and most physicians had been trained in a single area of practice [30, 31]. Therefore, to work in general practice/family medicine, physicians broaden their areas of practice to treat a wider range of patients. The major focus of the current revision of the board certification system to establish a two tier system of basic specialties and subspecialties, and to add general practice as a basic specialty [15]. Currently, the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine has extensively reviewed their board certification system. This will improve the quality of internists, regardless of their area of internal medicine practice.

There will soon be three types of physician working in the area of general practice/family medicine in Japan: those who originally trained with the intention of working in general practice/family medicine; those who trained in internal medicine, worked in a subspecialty and then broadened their area of practice; and those who had been working in areas other than general practice/family medicine and retrained (for example, a surgeon undergoing a career change). As the population ages, the greater demand for disease management will lead to greater demand for generalists, so more emphasis is needed on the training of different types of physicians in general/family practice. Such training must focus on more experienced doctors alike (in terms of continuing education), and those who have different backgrounds and experience.

This study had several limitations. First, the data set did not include data on Board-Certified Members of the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine; this certification is currently a condition for application for most subspecialties as well as application for Fellow of the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine. Second, the Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists only establishes whether the respondent is board certified at the time of the survey, and does not collect data on the date of initial certification or its expiry. As one certification is effective for 5 years, the 2-year study observation period could have underestimated the certification maintenance rate. Adding questions to the Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists, or establishing an integrated database of physicians’ career characteristics including board certification would overcome this limitation, but this would need the consensus of relevant stakeholders. Third, although the the Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists was designed as a census, some individuals did not respond, which might have affected the results. Finally, the main area of practice was self-reported so the actual practice pattern might be different.

Conclusions

Revision of the board certification system in internal medicine in Japan must consider physicians’ differing career paths, and take into account the needs of female physicians and flexibility to permit mid-career changes. Nevertheless, the quality of certification must be maintained, and the system must allow for sufficient numbers of physicians to be trained and distributed appropriately. It is also important to design programs to train specialists in general practice to meet the increasing demand for general/family practitioners.

Acknowledgments

Language editing services were provided by Convention Linkage, Inc. Tokyo Japan.

Funding

This study was supported by a Health Labour Sciences Research Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Tokyo, Japan (H26 Research on Statistics and Information 001) and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. (Grant Number JP16K00432).

Availability of data and materials

Raw data collected for the government statistics will not be shared due to restrictions stipulated by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Authors’ contributions

SK conceived the study, performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript. SK, MM, HI, HK, MS, and HY interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Soichi Koike was based at The Department of Health Management and Policy, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo until March 31, 2016, which is an endowed department. It received funds from Nissay Information Technology Co. Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Shionogi & Co. Ltd., Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation, CRECON Research & Consulting Inc., and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. The other coauthors have no conflicts of interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of the Graduate School of Medicine and Faculty of Medicine, The University of Tokyo approved the study. The requirement for consent from study subjects was waived, as this study was a secondary data analysis of government survey. Access to the survey data was approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Soichi Koike, Phone: +81-285-58-7394, Email: koikes@jichi.ac.jp.

Masatoshi Matsumoto, Email: matmo10@jb3.so-net.ne.jp.

Hiroo Ide, Email: ide@chiba-u.jp.

Hideaki Kawaguchi, Email: hikawaguchi-tky@umin.ac.jp.

Masahisa Shimpo, Email: shimpo@jichi.ac.jp.

Hideo Yasunaga, Email: yasunagah-tky@umin.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Chen J, Rathore SS, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Physician board certification and the care and outcomes of elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:238–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norcini JJ, Lipner RS, Kimball HR. Certifying examination performance and patient outcomes following acute myocardial infarction. Med Educ. 2002;36:853–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamashita K, Ikai H, Nishimura M, Fushimi K, Imanaka Y. Effect of certified training facilities for intensive care specialists on mortality in Japan. Crit Care Resusc. 2013;15:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan TA, Horwitz RI, Duffy FD, Cassel CK, Goode LD, Lipner RS. The role of physician specialty board certification status in the quality movement. JAMA. 2004;292:1038–1043. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.9.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes RS, Biester TW. Certification and maintenance of certification in surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:825–836. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis FR. Maintenance of certification: American Board of Surgery goals. Am Surg. 2006;72:1092–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stern PJ. Subspecialty certification in hand surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:165–168. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000224041.77215.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nestler SP, Roenigk RK. Accreditation and certification in dermatologic surgery. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2005;24:133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madewell JE. Lifelong learning and the maintenance of certification. J Am Coll Radiol. 2004;1:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollett WG, Waxman BP. Postgraduate surgical education and training in Canada and Australia: each may benefit from the other’s experiences. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82:581–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell RH. National curricula, certification and credentialing. Surgeon. 2011;9:S10–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeffe DB, Andriole DA. Factors associated with American Board of Medical Specialties member board certification among US medical school graduates. JAMA. 2011;306:961–970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists 2014. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/ishi/14/. Accessed 15 Feb 2017 (in Japanese).

- 14.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists 2012. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/ishi/12/. Accessed 15 Feb 2017 (in Japanese).

- 15.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Final Report of the Panel on Board Certification. April 22, 2013. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/2r985200000300ju.html. Accessed 15 Feb 2017 (in Japanese).

- 16.Japanese Medical Specialty Board. Program guideline for Board certification system (2016 December). http://www.japan-senmon-i.jp/news/doc/sinseibisisin2016.12.16.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2017 (in Japanese).

- 17.Watanabe T. Overview of the new internal medicine board certification system in Japan: from a historical perspective. Journal of the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine. 2015;104:1152–1159. doi: 10.2169/naika.104.1152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Japanese Society of Internal Medicine. Outline of the Board Certified Member of the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine. http://www.naika.or.jp/nintei/seido/gaiyo/. Accessed 15 Feb 2017 (in Japanese).

- 19.Ito Y. Surgical education and postgraduate training in Japan. World J Surg. 2008;32:2134–2137. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9638-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koike S, Shimizu A, Matsumoto M, Ide H, Atarashi H, Yasunaga H. Career pathways of board-certified surgeons in Japan. Surg Today. 2016;46:661–675. doi: 10.1007/s00595-015-1212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi S, Teramoto A. The current state of neurosurgery in Japan. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:864–870. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goto Y. Specialist training and certification process for anaesthesiologist in Japan. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1994;23:630–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshimoto S, Nakashima T, Fujii T, Matsuura K, Otsuki N, Asakage T. Japanese board certification system for head and neck surgeons. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2014;41:327–330. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horikawa N, Kuroki N, Hosaka T, Nomura S, Nishimura H, Yamashita K, et al. Introduction of a board certification system for the Japanese Society of General Hospital Psychiatry. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2003;105:320–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimada N, Kondo T. Estimation of actual report rate using data from the survey of physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2004;51:117–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey Questionnaire of the Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/chousahyo/index.html#00450026. Accessed 15 Feb 2017 (in Japanese).

- 27.The Japanese Society of Internal Medicine. Toward New Internal Medicine Board Certification System. http://www.naika.or.jp/jsim_wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/newfellow4.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2017 (in Japanese).

- 28.Matsumoto M, Okayama M, Inoue K, Kajii E. High-tech rural clinics and hospitals in Japan: a comparison to the Japanese average. Aust J Rural Health. 2004;12:215–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Current Status of the Main Facility Criterion Notification. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-12404000-Hokenkyoku-Iryouka/0000101005.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2017 (in Japanese).

- 30.Otaki J. Considering primary care in Japan. Acad Med. 1998;73:662–668. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199806000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith BW, Demers R, Garcia-Shelton L. Family medicine in Japan. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:59–62. doi: 10.1001/archfami.6.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data collected for the government statistics will not be shared due to restrictions stipulated by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.