Abstract

Background

Throughout history, every civilization in the world used plants or their derivatives for treatment or prevention of diseases. In Palestine as in many other countries, herbal medicines are broadly used in the treatment of wide range of diseases including urological diseases. The main objective of this research is to study the use of herbal remedies by herbalists and traditional healers for treatment of various urological diseases in the West Bank regions of Palestine and to assess their efficacy and safety through the literature review of the most cited plants.

Method

The study included a survey part, plant identification and a review study. The first part was a cross-sectional descriptive study. Face to face questionnaires were distributed to 150 traditional healers and herbalist in all regions of the West Bank of Palestine. The literature review part was to assess the most cited plants for their efficacy and toxicity.

Results

One hundred forty four herbalists and traditional healers accepted to participate in this study which was conducted between March and April, 2016. The results showed that 57 plant species belonging to 30 families were used by herbalists and traditional healers for treatment of various urinary tract diseases in Palestine. Of these, Apiaceae family was the most prevalent. Paronychia argentea, Plantago ovata, Punica granatum, Taraxacum syriacum, Morus alba and Foeniculum vulgare were the most commonly used plant species in the treatment of kidney stones, while Capsella bursa-pastoris, Ammi visnaga and Ammi majus were the most recommended species for treatment of urinary tract infections and Portulaca oleracea used for renal failure. In addition Curcuma longa and Crocus sativus were used for enuresis while Juglans regia, Quercus infectoria, Sambucus ebulus and Zea mays were used for treatment symptoms of benign prostate hyperplasia. Fruits were the most common parts used, and a decoction was the most commonly used method of preparation. Through literature review, it was found that Paronychia argentea has a low hemolytic effect and contains oxalic acid and nitrate. Therefore, it could be harmful to renal failure patients, also Juglans regia, Quercus infectoria and, Sambucus ebulus are harmful plants and cannot be used for treatment of any disease.

Conclusions

Our data provided that ethnopharmacological flora in the West Bank regions of Palestine can be quite wealthy and diverse in the treatments of urinary tract diseases. Clinical trials and pharmacological tests are required evaluate safety and efficacy of these herbal remedies.

Keywords: Ethnopharmacology, Urological diseases, Herbalists, Traditional healers, Palestine

Background

Traditional herbal medicine is an important part of all nations’ history, therefore, an establishment of the original uses and local names of plants has significant potential societal benefits. Unfortunately, recently with the fast growth in the technical aspects of the world, loss of customs and various ethnic cultures, some of this information may disappear [1–3]. Since the beginning of history, human beings have used plants as medicine, and Ancient Arabic Medicine was influenced by medicinal practices in India, Persia, Mesopotamia, Spain, Rome and Greece [4].

Palestine had high ecosystem diversity due to its geographical location between Africa, Asia, and Europe and due to different climatic, zoogeographic, and phytogeographic zones, this creates great biological diversity [5, 6]. In the West Bank regions of Palestine, traditional medicine is widely used especially in rural areas; this may be due to the political conflicts in this country and the cost of conventional drugs [7–9]. Hundreds of shrubs, trees, and herbal species used as antipyretics, analgesics, diuretics, laxatives, antimicrobial, antidiarrheal, emetics and cardio-tonics in the West Bank area of Palestine [10]. These plants are available and cheap because they grow wildly in nature or cultivated [11, 12].

The rich variety of approaches employed by herbalists and traditional healers to treat disorders and diseases of the urinary tract is indicative of the depth and breadth of indigenous medicine practiced among these traditional healers and herbalists in the twentieth century [12].

The Kidney is the organ that has numerous physiological functions. Its role is to maintain the homeostatic balance of body fluids and electrolytes. Kidneys are vital regulators of glucose metabolism, blood pressure, and erythropoiesis. Patients with kidney diseases have significant morbidity and mortality [13, 14].

There are many urologic diseases and disorders. According to the American Urological Association Foundation, the most commonly identified urological diseases include hyperplasia, benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH), urinary tract infections, urethral and kidney stones, enuresis (urinary incontinence) and renal failure [15].

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics and Ministry of Health annual report in 2014, the visits to the outpatient urological clinics of governmental hospitals in Palestine were 49,275 visits per year. Moreover, about 4% of death causes in Palestine were due to renal failure and other kidney diseases. In the USA, about 26 million American adults have kidney disease, and it is considered the 9th leading cause of death in the United States. Kidney diseases kill more people than breast or prostate cancer yearly [16–18].

For these reasons, this study aimed to collect data from herbalists and traditional healers about the folk herbal remedies, which have been utilized for treatment of urological diseases in the West Bank regions of Palestine and to verify their pharmacological and toxicological effects through literature review.

Methods

Study areas

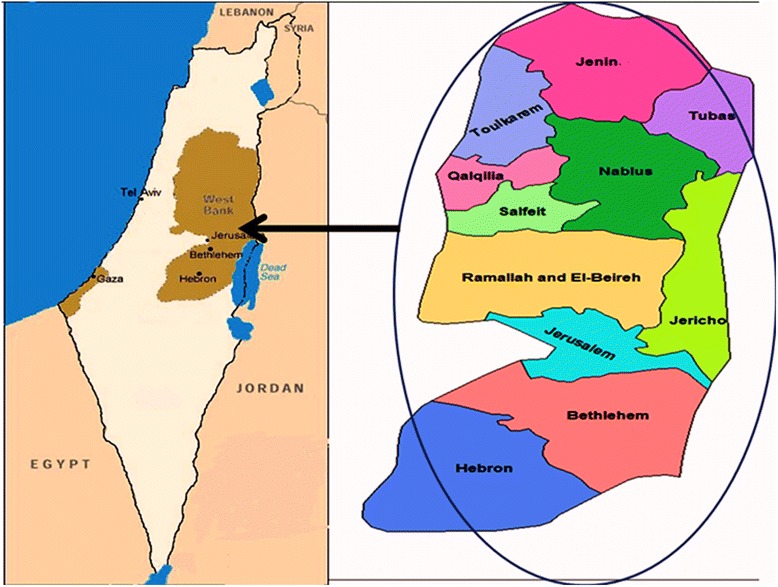

West Bank is an important territory of Palestine. The climate in the West Bank is mostly Mediterranean, slightly colder in mountains and hills compared with the shorelines in the western lands. In the east, it includes the desert and the shoreline of the Dead Sea, both with dry and hot climate. The shores of the Dead Sea are about 430 m below sea level, and it is considered the Earth’s lowest elevation on the land. Accordingly, all these factors explain the enormous diversity of the West Bank flora. This diversity is directly reflected in the distribution and diversification of agricultural patterns, from the rain-fed farming in the mountains (Jerusalem, Ramallah, Hebron, Nablus, Bethlehem, Salfeit) to an irrigated agriculture as in Jenin, Tobas, Toulkarem, Qalqilya and Jericho lands [19, 20].

Selection of informants

An ethnopharmacological survey (questionnaire-based cross-sectional descriptive study) was used. Areas visited included all regions of the West Bank/Palestine, including Nablus, Jenin, Tubas, Toulkarem, Salfeit, Qalqilya, Ramallah, Jericho, Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Hebron (Fig. 1) between March and April 2016. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at An-Najah National University approved the study protocol and the informed consent forms (IRB number was 134/February/2016). The study was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the declarations of Helsinki (World Medical Association 2008), the current Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Guidelines (EME 1997) and the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH1996) Guidelines, and a written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Fig. 1.

The study area map showing all the surveyed regions in the West Bank/Palestine

The objectives of the study were explained to the participants, they were not offered any incentives, and they were able to withdraw from this study at any time.

A total of 150 traditional healers and herbalists were interviewed in this study. 144 participants accepted to answer the questionnaire (102 males and 42 females), where 26 of them were from Hebron (16 males and 10 females), 18 from Jenin (12 males and 6 females), 17 from Jericho (14 males and 3 females), 16 Nablus and Qalqilya (12 males and 4 females from Nablus) (10 males and 6 females from Qalqilya), 14 from Toulkarem (12 males and 2 females), 11 from Ramallah (9 males and 2 females), 9 from Jerusalem (7 males and 2 females), 6 from Tubas and Jerusalem (4 males and 2 females from Tubas) and (3 males and 3 females from Jerusalem), and 5 from Salfeit (3 males and 2 females), from 11 regions of the West Bank Area of Palestine. They were from different ages (22–91 years) and were selected with the help of local people. The selected healers were well known in the community due to their long practice of providing services related to traditional health care. All the participants (i.e., 144) were asked to provide information on the plant(s) that they use for treating the urinary tract diseases, parts of the plants used such as leaves, roots, flowers, stems and seeds, methods of preparation (e.g decoction, juice, infusion, powder), and methods of administration (either orally or topically). In addition to their opinion about the advantages of herbal remedies.

The study was a face to face questionnaire. This method has proven to be a very practical and useful option of data collection. The survey was anonymous, pretested by a pilot study for reliability, validity and clarity of the questionnaire. Meanwhile, the duration of the interviews ranged from 20 to 60 min, with one visit per interviewee in each case. Interviews were conducted in Arabic, the local language of the informants and the plant names were given in Arabic and later translated into English and Latin using reference books as well as about 50% of these Arabic names were linked to an actual right scientific name [21–23].

Plant identification

The collected plant samples from these informants were stored in the pharmacognosy laboratory at the Pharmacy Department, An-Najah National University in appropriate glassware and individual herbarium wooden frames. They were identified later by a team of teaching assistants and technicians under the supervision of the pharmacognosist (Dr. Nidal Jaradat), all fifty-seven plants’ species that were mentioned by informants, were identified by using photographs from reference books and dried herbarium specimens [24, 25].

Data analysis

The frequency of citation (FC) for all plants species in this study were calculated by using the following formula:

FC = (Number of times a particular species was mentioned by herbalists and traditional healers/a total number of occasions that all species were mentioned) × 100 [24].

To evaluate the relative importance of plants in indigenous healthcare systems, the use value (UV) is used as a micro-statistical tool, which reflects people interaction with specific plants as the best treatments for urinary tract diseases. It is a quantitative method that can be used to prove the relative importance of species known locally. It can be calculated according to the following equation:

Where UV is the use value of a species; U is the number of citations per species; n is the number of informants [25].

Factor of informant’s consensus (Fic) was calculated according to the following equation:

Where Nur is the number of use citations in urinary tract disease category, and Nt is the number of taxa used for the treatment of these diseases.

This factor is employed to indicate how homogenous the information is. Fic value is close to 0 if plants are chosen randomly, or if informants do not exchange information about their use. High values of Fic (close to 1) occur when there is a clear selection criterion in the community and if information is frequently exchanged between informants [26].

The Choice Value (CV) method is a valuable assessment tool to measure related plant species for treatment of urinary tract diseases [27].

The CV is calculated as in the following equation:

Pcs: percent of informants that cited certain plant species for the treatment of urinary tract disease.

Sc: is the total number of species mentioned for treatment of disease by all informants. Choice values are ranked from 0 to 100 with 100 indicating complete preference and fewer alternatives.

The significance of medicinal plant families was assessed using the Family Use Values (FUV), which was calculated according to the following equation:

where, UVs = use values of the taxa, and ns = total number of species within each family which were used for the treatment of urological diseases in the West Bank area of Palestine [28].

Review study

A literature review was conducted by a systematic search of the scientific literature, which was published before January 2017, by using Medline, Pubmed, Scopus and Google Scholar electronic searching machines. It cited most of the plants which had FC higher than 50% and their applications in the treatment of urological disease. The investigators practiced the following Keywords: folk uses for urinary tract, ethnopharmacological uses urinary tract, traditional methods of urinary tract, evidence-based uses, toxicities and side effects for individual plant names.

Results

Socio-demographic factors

As shown in Table 1, most of the respondents who worked in this field were males. Most of them had high educational levels. In fact, 30.56% of the interviewed were secondary school graduates. The majority of respondents were from areas of the West Bank that mostly depended on agriculture or grazing as a mean of income (Hebron, Jenin, and Jericho).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic factors related to the respondents

| Variable | Number of herbalists and traditional healers (N = 144) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 102 |

| Female | 42 |

| Education level | |

| No formal education | 32 |

| Elementary | 14 |

| Secondary school | 28 |

| High secondary school | 44 |

| Undergraduate | 22 |

| Graduate (higher education) | 4 |

| Residency | |

| Bethlehem | 6 |

| Hebron | 26 |

| Jenin | 18 |

| Jericho | 17 |

| Jerusalem | 9 |

| Nablus | 16 |

| Qalqilya | 16 |

| Ramallah | 11 |

| Salfeit | 5 |

| Tubas | 6 |

| Toulkarem | 14 |

| Age (mean ± SD) years | 54.8 ± 17.9 |

| Experience (mean ± SD) years | 29.1 ± 10.9 |

Regarding training and knowledge acquisition; (i) 77% of the respondents acquired their skills through observing their family members, (ii) 21% gained their skills through coursework and apprenticeship, (iii) and about 2% claimed they had a divine gift for the healing of certain diseases, which means that most of them had this knowledge through their families’ historical healing knowledge skill.

Data collection of ethnopharmacological plants.

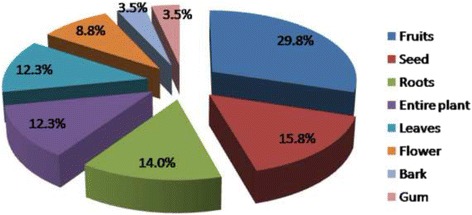

The fruits were the most commonly used parts of plants for the treatment of urinary tract diseases followed by seeds and roots. The modes and methods of preparation varied considerably from one healer to another; however, all of these methods were administered orally as described by the interviewees and shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The medicinal plants used for the treatment of some urinary tract diseases, the plant parts used, use values, choice value, frequency of citation, modes and methods of preparation

| Scientific names | Arabic local names | English common names | Family | Voucher specimen codes | Urinary tract diseases | Part used and mode of preparation | Method of preparation | # Informant 144 | FC, % | UV | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paronychia argentea Lam. | رجل الحمام | Chickweed, Algerian tea | Caryophyllaceae | Pharm-PCT-1793 | Kidney stones | Entire plant/Boil about 100 g of the plant in 100 ml water. 30 ml of this decoction is to be given orally before each meal. | Decoction | 140 | 97.22 | 0.97 | 1.71 |

| Curcuma longa L. | كركم | Turmeric | Zingiberaceae | Pharm-PCT-2709 | Enuresis | Roots/Steep 150 g of the roots in 200 ml water for two hours. This infusion is to be given after each meal. | Infusion | 135 | 93.75 | 0.94 | 1.64 |

| Plantago ovata Forssk. | لسان الحمل البيضوي | Blond Psyllium | Plantaginaceae | Pharm-PCT-1891 | Kidney stones | Seeds/About 50 g of dried and ground seeds are to be given orally once daily. | Powder | 134 | 93.06 | 0.93 | 1.63 |

| Portulaca oleracea L. | فرفحينه | Common Purslane | Portulacaceae | Pharm-PCT-1935 | Renal failure | Entire plant/10 drops of the fresh plant juice are to be given twice daily. | Juice | 134 | 93.06 | 0.93 | 1.63 |

| Punica granatum L. | رمان | Pomegranate | Lythraceae | Pharm-PCT-2721 | Kidney stones | Fruits/300 ml of Pomegranate juice obtained from the fruits is to be given five times a day. | Juice | 133 | 92.36 | 0.92 | 1.62 |

| Juglans regia L. | جوز | Walnuts | Juglandaceae | Pharm-PCT-2714 | Prostatic enlargement | Bark/Boil 100 g from the ground bark in 300 ml water for 30 min. 50 ml of this decoction is to be given twice daily. | Decoction | 132 | 91.67 | 0.92 | 1.61 |

| Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik. | کیس الراعي | Shepherd’s-Purse | Brassicaceae | Pharm-PCT-497 | Urinary tract infection | Fruits/ Boil about 100 g from the ground fruits in 300 ml water. Give 100 ml three times a day after meals. | Decoction | 132 | 91.67 | 0.92 | 1.61 |

| Quercus infectoria subsp. veneris (A.Kern.) Meikle | بلوطحلبي | Aleppo Oak | Fagaceae | Pharm-PCT-1977 | Prostatic enlargement | Entire plant/Boil about 50 g of the any plant part in 200 ml water. 50 ml of this decoction is to be given four times a day with meals. | Decoction | 119 | 82.64 | 0.83 | 1.45 |

| Crocus sativus L. | زعفران | Saffron | Iridaceae | Pharm-PCT-2733 | Enuresis | Flowers/Steep 40 g of the flowers in 100 ml boiled water for 8 h. 15 ml from this infusion is to be given two times a day | Infusion | 118 | 81.94 | 0.82 | 1.44 |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa L. | كركديه | Roselle | Malvaceae | Pharm-PCT-2752 | Urinary tract infection | Flower/Boil about 150 g of the plant in 100 ml water. 40 ml of this decoction is to be given orally before each meal. | Decoction | 112 | 77.78 | 0.78 | 1.36 |

| Ammi visnaga (L.) Lam. | الخله المصريه | Khella | Apiaceae | Pharm-PCT-139 | Urinary tract infection | Fruits/Boil about 250 g of the plant in 500 ml water. 100 ml of this decoction is to be given orally three to five times a day. | Decoction | 102 | 70.83 | 0.71 | 1.24 |

| Ammi majus L. | الخله الشيطانيه | Bishop’s Flower, Bishop’s weed | Apiaceae | Pharm-PCT-138 | Urinary tract infection | Fruits/Boil about 30 g of fruits in 100 ml water for 5 min. This decoction is to be given three times a day after meals. | Decoction | 98 | 68.06 | 0.68 | 1.19 |

| Taraxacum syriacum Boiss. | هندباء | Silkweed | Compositae | Pharm-PCT-2396 | Kidney stones | Roots/Boil about 300 g of the plant in 500 ml water. 100 ml of this decoction is to be given orally before each meal. | Decoction | 95 | 65.97 | 0.66 | 1.16 |

| Sambucus ebulus L. | البيلسان | Danewort | Adoxaceae | Pharm-PCT-2135 | Enuresis, prostatic enlargement. | Leaves/Steep 200 g of the powdered leaves in 500 ml boiled water for 12 h. About 100 ml from this infusion is to be given three times daily. | Infusion | 92 | 63.89 | 0.64 | 1.12 |

| Morus alba L. | توت ابيض | White Mulberry | Moraceae | Pharm-PCT-2750 | Kidney stones | Fruits/150 ml of fresh juice are to be given orally every two hours. | Juice | 91 | 63.19 | 0.63 | 1.11 |

| Zea mays L. | ذره | Maize | Poaceae | Pharm-PCT-2747 | Prostatic enlargement, urinary tract infections | Flower stigmas (corn silk) | Infusion | 72 | 50.00 | 0.58 | 1.02 |

| Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | شومر | Fennel | Apiaceae | Pharm-PCT-1041 | Kidney stones, urinary tract infection | Fruits/ Boil about 50 g of the fruits in 50 ml water. 25 ml of this decoction is to be given three times a day. | Decoction | 78 | 54.17 | 0.54 | 0.95 |

| Daucus carota L. | جزر بري | Wild carrot | Apiaceae | Pharm-PCT-829 | Urinary tract infection | Fruits/ Boil about 150 g of the powder in 600 ml water. About 150 ml of this decoction is to be given three times a day. | Decoction | 69 | 47.92 | 0.48 | 0.84 |

| Buddleja coriacea Remy | عفار | Butterfly bush | Scrophulariaceae | Pharm-PCT-2746 | Enuresis | Flowers/Boil about 20 g of the flowers in 200 ml water. About 50 ml of this decoction is to be given once daily. | Infusion | 67 | 46.53 | 0.47 | 0.82 |

| Persea americana Mill. | افوكادو | Avocado | Lauraceae | Pharm-PCT-2740 | Enuresis | Leaves/Boil about 50 g of leaves in 150 ml water for 5 min. This decoction is to be given three times a day after meals. | Decoction | 66 | 45.83 | 0.46 | 0.80 |

| Cucurbita pepo L. | قرع | Pumpkin | Cucurbitaceae | Pharm-PCT-2762 | Prostatic enlargement | Seeds/ Boil about 100 g of the seeds in 600 ml water. About 50 ml of this decoction is to be given three times a day. | Decoction | 66 | 45.83 | 0.46 | 0.80 |

| Equisetum ramosissimum Desf. | كنباث أفرع | Branched Horsetail | Equisetaceae | Pharm-PCT-915 | Renal failure | Entire plant/ Boil about 50 g of the powder in 600 ml water. About 100 ml of this decoction is to be given three times a day. | Decoction | 66 | 45.83 | 0.46 | 0.80 |

| Ferula communis L. | كلخ | Common Giant Fennel | Apiaceae | Pharm-PCT-1016 | Kidney stones | Fruits/Steep 50 g of the plant in 150 ml boiled water for 12 h. 10 ml from this infusion is to be given two times a day | Infusion | 65 | 45.14 | 0.45 | 0.79 |

| Rosa canina L. | ورد السياج | Rose hips, Dog-rose | Rosaceae | Pharm-PCT-2052 | Urinary tract infection | Fruits/Boil about 70 g of leaves in 150 ml water for 15 min. This decoction is to be given three times a day after meals. | Decoction | 65 | 45.14 | 0.45 | 0.79 |

| Ficus sycomorus L. | جميز | Fig-Mulberry | Moraceae | Pharm-PCT-1030 | Urinary tract infection, renal failure | Fruits/Extract 100 ml of juice to be given orally five times a day. | Juice | 63 | 43.75 | 0.44 | 0.77 |

| Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss | بقدونس | Garden Parsley | Apiaceae | Pharm-PCT-2739 | Prostatic enlargement, urinary tract infections, kidney stones | Fruits/Boil about 100 g from the powdered fruits in 600 ml water. About 150 ml from this decoction is to be given 4–5 times daily. | Decoction | 44 | 30.56 | 0.43 | 0.76 |

| Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. | الصمغ العربي | Arabic Gum | Leguminosae | Pharm-PCT-2755 | Kidney stones | Gum/About 20 g of gum are to be given orally twice daily with a cup of milk. | Powder | 61 | 42.36 | 0.42 | 0.74 |

| Raphanus raphanistrum L. | فجل بري | Radish | Brassicaceae | Pharm-PCT-2007 | Kidney stones | Seeds/ Boil about 250 g of the powder in 750 ml water. About 150 ml of this decoction is to be given three times a day. | Decoction | 59 | 40.97 | 0.41 | 0.72 |

| Olea europaea L. | زيتون | Olive | Oleaceae | Pharm-PCT-1664 | Renal failure | Fruits/Three table spoons of Olive oil is to be given orally twice a day. | Oil | 57 | 39.58 | 0.40 | 0.69 |

| Apium graveolens L. | كرفس | Celery | Apiaceae | Pharm-PCT-204 | Prostatic enlargement | Entire plant/Ten drops of Celery entire plant juice are to be given orally three times a day. | Juice | 56 | 38.89 | 0.39 | 0.68 |

| Astracantha gummifera (Labill.) Podlech | الكثيراء | Tragacanth | Leguminosae | Pharm-PCT-2754 | Kidney stones | Gum/About 50 g of gum are to be given orally three times daily with 2 cups of water. | Powder | 55 | 38.19 | 0.38 | 0.67 |

| Urtica pilulifera L. | القريص الشائك | Roman Nettle | Urticaceae | Pharm-PCT-2561 | Kidney stones, Urinary tract infections | Roots/Boil about 20 g of the powder in 100 ml water. About 30 ml of this decoction is to be given three times a day. | Decoction | 55 | 38.19 | 0.38 | 0.67 |

| Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng. | عنب الدب | Bearberry | Ericaceae | Pharm-PCT-2705 | Urinary tract infection | Leaves/Boil about 90 g from the dried leaves in 400 ml water. About 50 ml from this decoction is to be given 3–5 times daily. | Decoction | 55 | 38.19 | 0.38 | 0.67 |

| Cinnamomum verum J.Presl | قرفه | Cinnamon | Lauraceae | Pharm-PCT-2707 | Prostatic enlargement | Bark/ Boil about 80 g from the dried powdered plant in 400 ml water. About 50 ml from this decoction is to be given 3–5 times daily. | Decoction | 54 | 37.50 | 0.38 | 0.66 |

| Angelica archangelica L. | حشيشة الملاك | Wild Celery | Apiaceae | Pharm-PCT-2758 | Kidney stones | Roots/Boil about 100 g from the dried powdered plant in 500 ml water. About 50 ml from this decoction is to be given 4–5 times daily. | Decoction | 51 | 35.42 | 0.35 | 0.62 |

| Lolium temulentum L. | زوان مسكر | Darnel | Poaceae | Pharm-PCT-1453 | Enuresis | Seeds/Boil about 200 g from the dried powdered plant in 500 ml water. About 100 ml from this decoction is to be given twice daily. | Decoction | 44 | 30.56 | 0.31 | 0.54 |

| Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal | سموه | Ashwagandha | Solanaceae | Pharm-PCT-2678 | Kidney stones | Roots/Boil about 50 g of the powder in 100 ml water. About 50 ml of this decoction is to be given three times a day after meals. | Decoction | 43 | 29.86 | 0.30 | 0.52 |

| Origanum jordanicum Danin & Kunne | زعتر | Thyme | Lamiaceae | Pharm-PCT-1729 | Kidney stones | Leaves/Boil about 60 g of leaves in 200 ml water for 5 min. This decoction is to be given three times a day after meals. | Decoction | 42 | 29.17 | 0.29 | 0.51 |

| Barbarea vulgaris R.Br. | جرجير بري | Rocketcress | Brassicaceae | Pharm-PCT-2757 | Urinary tract infection | Leaves/Steep 40 g of the powdered leaves in 100 ml water for12 hours. About 30 ml from this infusion is to be given three times daily. | Infusion | 42 | 29.17 | 0.29 | 0.51 |

| Jateorhiza palmata (Lam.) Miers | ساق الحمام | Calumba | Menispermaceae | Pharm-PCT-2753 | Urinary infections | Flowers/Steep 200 g of the powdered flowers in 800 ml water for 8 h. About 50 ml from this infusion is to be given three times daily. | Infusion | 40 | 27.78 | 0.28 | 0.49 |

| Viola kitaibeliana Schult. | بنفسج | Dwarf Pansy | Violaceae | Pharm-PCT-2656 | Kidney stones | Seeds/About 10 drops of seeds oil is to be given orally twice daily. | Oil | 35 | 24.31 | 0.24 | 0.43 |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra L. | عرق السوس | Licorice | Leguminosae | Pharm-PCT-1128 | Enuresis | Roots/Steep 50 g of the powdered roots in 300 ml water for 12 h. About 100 ml from this infusion is to be given four times daily. | Infusion | 34 | 23.61 | 0.24 | 0.41 |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | ريحان | Basil | Lamiaceae | Pharm-PCT-2717 | Kidney stones | Leaves/Steep100 grams of the powdered leaves in 400 ml water for 6 h. About 50 ml from this infusion is to be given five times daily. | Infusion | 32 | 22.22 | 0.22 | 0.39 |

| Hypericum perforatum L. | سانت جون | St John’s Wort | Hypericaceae | Pharm-PCT-2734 | Kidney stones | Flowers Boil about 30 g of plant in 100 ml water for 25 min. This decoction is to be given three times a day after meals. | Decoction | 32 | 22.22 | 0.22 | 0.39 |

| Fragaria vesca L. | فراوله | Strawberry | Rosaceae | Pharm-PCT-2763 | Urinary tract infection | Fruits/ Extract 150 ml of juice to be given orally four times a day. | Juice | 29 | 20.14 | 0.20 | 0.35 |

| Cyperus longus L. | بردي | Sweet Cyperus | Cyperaceae | Pharm-PCT-808 | Renal failure | Entire plant/ Boil about 10 g from the dried powdered plant in 100 ml water. About 20 ml from this decoction is to be given 5–6 times daily. | Decoction | 22 | 15.28 | 0.15 | 0.27 |

| Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. | حنظل | Bitter apple | Cucurbitaceae | Pharm-PCT-628 | Kidney stones | Seed/ Steep 40 g of the grounded seeds in 100 ml water for 12 h. 25 ml from this infusion is to be given three times a day | Infusion | 21 | 14.58 | 0.15 | 0.26 |

| Brassica nigra (L.) K.Koch | خردل اسود | Black mustard | Brassicaceae | Pharm-PCT-408 | Kidney stones | Seeds/ Steep 50 g of the powder in 300 ml water for four hours. 100 ml of this infusion is to be given 4–5 times a day. | Infusion | 18 | 12.50 | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| Helichrysum sanguineum (L.) Kostel. | دم المسيح | Red everlasting | Compositae | Pharm-PCT-1170 | Renal failure | Entire plant/ Steep 100 g of the powdered plant in 100 ml water for 8 h. About 30 ml from this infusion is to be given three times a day. | Infusion | 17 | 11.81 | 0.12 | 0.21 |

| Lupinus angustifolius L. | الترمس ضيق الأوراق | Blue lupin | Leguminosae | Pharm-PCT-1477 | Urinary tract infection | Roots/ Boil 50 g of the roots in 500 ml water for 30 min. 100 ml of this decoction is to be given twice a day. | Decoction | 16 | 11.11 | 0.11 | 0.19 |

| Phaseolus vulgaris L. | فاصولياء | Common Bean | Leguminosae | Pharm-PCT-2748 | Renal failure | Seeds/ Boil about 40 g of the seeds in 500 ml water. 100 ml of this decoction is to be given three times a day with meals. | Decoction | 13 | 9.03 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

| Vitex agnus-castus L. | كف مريم | Chaste Tree | Lamiaceae | Pharm-PCT-2663 | Renal failure | Fruits/ Extract 200 ml of juice to be given orally five times a day. | Juice | 13 | 9.03 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

| Prunus avium (L.) L. | كرز حلو | Wild cherry | Rosaceae | Pharm-PCT-2751 | Kidney stones | Fruits/ About 100 ml of fresh Wild Cherry juice are to be given orally four times a day. | Juice | 8 | 5.56 | 0.06 | 0.10 |

| Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. | قصب بري | Common Reed | Poaceae | Pharm-PCT-1843 | Renal failure | Roots/ Boil about 200 g of the roots in 500 ml water. 100 ml of this decoction is to be given four times a day. | Decoction | 8 | 5.56 | 0.06 | 0.10 |

| Malvella sherardiana (L.) Jaub. & Spach | خبيزة بريه | Field Mallow | Malvaceae | Pharm-PCT-1508 | Renal failure | Leaves/ Steep 20 g of the powdered leaves in 150 ml water for 2–3 h. About 50 ml from this infusion is to be given three times daily. | Infusion | 7 | 4.86 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Capsicum annuum L. | الفليفلة الشجيرية | Chili pepper | Solanaceae | Pharm-PCT-2729 | Urinary tract infections | Fruits/ About 10 g of ground dried fruits are to be given orally twice daily with a cup of water. | Powder | 7 | 4.86 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Carica papaya L. | ببايا | Papaya | Caricaceae | Pharm-PCT-2761 | Kidney stones | Seeds/ About 10 g of ground seeds are to be given orally twice daily. | Powder | 5 | 3.47 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

In the case of kidney stones, the highest use values were for Paronychia Argentina, Plantago ovata, Punica granatum, Taraxacum syriacum, Morus alba and Foeniculum vulgare, respectively. In the case of urinary tract infections, the highest use values were for Capsella bursa-pastoris, Ammi visnaga, and Ammi majus, respectively. Besides, the maximum use value in case of renal failure was for Portulaca oleracea while the highest use values in the case of enuresis were for Curcuma longa and Crocus sativus, respectively. In the case of prostatic enlargement, the highest use values were for Juglans regia, Quercus infectoria, Sambucus ebulus and Zea mays, respectively. Furthermore, the frequencies of citation for these plants species were more than 50%.

The factor of informant’s consensus (Fic) was calculated for medicinal plants used for the treatment of various urinary tract diseases (i.e., 0.99 for Benign Prostate Hyperplasia (BPH) and enuresis and 0.98 in a case of kidney stones disease, urinary tract infection and renal failure). The calculated Fic value obtained for the reported diseases indicated the degree of shared knowledge among informants for the treatment of these urinary tract diseases by certain medicinal plants as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Factor of informant’s consensus (Fic) for the studied urinary tract diseases

| Urinary tract disease categories | Nt | Nur | Fic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney stones | 22 | 1202 | 0.98 |

| Urinary infection | 17 | 912 | 0.98 |

| Prostatic enlargement | 8 | 544 | 0.99 |

| Enuresis | 7 | 496 | 0.99 |

| Renal failure | 10 | 370 | 0.98 |

Where; Nur is the number of use citations in urinary tract disease category, Nt is the number of taxa used for treatment of these diseases.

Ethnopharmacological information obtained from the study area on medicinal plants used in the treatment of various urinary tract diseases revealed that 57 plant species belonging to 30 families. All of the Latin scientific names have been checked with www.theplantlist.org on March 10, 2016.

As presented in Table 4, the family use value was the highest for Apiaceae family, which was 26.67, where the most common plant parts used were fruits, seeds, and roots, respectively as shown in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Medicinal plant families used for treatment of urinary tract diseases and the family use value (30 families)

| Number | Families | Number of taxa | Family use value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Apiaceae | 8 | 26.67 |

| 2. | Lamiaceae | 5 | 16.67 |

| 3. | Leguminosae | 5 | 16.67 |

| 4. | Brassicaceae | 4 | 13.33 |

| 5. | Poaceae | 3 | 10.00 |

| 6. | Rosaceae | 3 | 10.00 |

| 7. | Compositae | 2 | 6.67 |

| 8. | Cucurbitaceae | 2 | 6.67 |

| 9. | Malvaceae | 2 | 6.67 |

| 10. | Moraceae | 2 | 6.67 |

| 11. | Solanaceae | 2 | 6.67 |

| 12. | Other families with one citation | 19 | 63.33 |

Fig. 2.

The frequency of the used parts of medicinal plants in the treatment of some urinary tract diseases

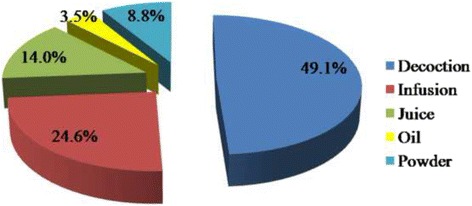

Pharmaceutical preparations

The methods of preparation were decoctions, infusions, juice, oil, and powder. Decoctions and infusions were the most frequently used methods of preparation as presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The frequency of preparation methods of medicinal plants for treatment of some urinary tract diseases

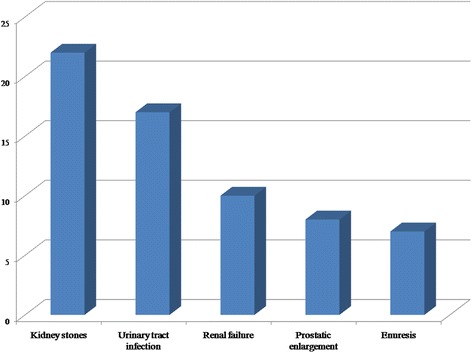

The most common urinary tract disease treated with herbal remedies was kidney stones followed by urinary tract infections, renal failure, Benign Prostate Hyperplasia (BPH) and enuresis as reported in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The frequency of urinary tract diseases mentioned by herbalists and traditional healers in the West Bank area of Palestine

Literature review

For all the listed above plants, a literature review was investigated, where it represented their ethnopharmacological use against urinary tract diseases regionally, internationally and globally. Also, in-vitro as well as in-vivo studies and their toxic or adverse reactions were reviewed for plants which had FC value more than 50%, using electronic databases and the results were summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of published ethnopharmacology, in vivo, in vitro studies, side effects and toxicity of the most frequently recommended plants for treatment of urinary tract diseases

| Urinary tract diseases | Plant species | Ethnopharmacological usage for treatment of various urinary tract diseases and country with reference source | In-vitro and in-vivo studies on plants used for treatment of various urinary tract diseases with reference source | Side effects and toxicity of plants used for treatment of various urinary tract diseases with reference source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney stones | Paronychia argentea | Turkey [30] Jordan [26, 31, 32], Palestine [33, 34], Spain [35], Egypt [36], and Algeria [37]. | In-vitro study on wistar rats it prevented and reduced the growth of kidney stones in experimental calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis [38]. | In-vitro study proved that P. argentea extract had low hemolytic effect [39] as well as the butanolic extract of P. argentea can prevent or slow down the oxidative damage induced by organophosphorus pesticide, chloropyriphos ethyl in rats [38]. |

| Plantago ovata | No references found about its folk usage for treatment of kidney stones. | In vitro study on rats proved that intake of a P. ovata husk-supplemented diet prevented endothelial dysfunction [40]. | Arabinoxylan from Plantago ovata husks had been proven its safety scientifically on rats and rabbits [41]. | |

| Punica granatum | India and North Africa [42–45]. | On male rats experiment proved that the administration of P. granatum induced urolithiatic rats resulted in removal of deposition of calcium oxalate crystals into kidneys and improving renal histology [46]. In another experiment on rats showed the protective effect of p. granatum in the ethylene glycol induced crystal depositions in kidneys [47]. |

No references | |

| Taraxacum syriacum | No references | No references | No references | |

| Morus alba | Bulgaria and Italy [48]. | Ethanlic leaves extract showed significant anti-nephrolithiatic effect in wistar rats [49]. | No reference | |

| Foeniculum vulgare | United Kingdom [50], Palestine [51], Italy [52], Turkey [53], Bosnia [54], Serbia [55], Iran [10, 56, 57], Pakistan [58], India [59], and Bolivia [60]. | Herbal beverage of F. vulgare inhibited of calcium oxalate renal crystals formation in rats [61]. | In most toxicity experiments carried out on F. vulgare, no signs of toxicity were observed [62]. | |

| Urinary tract infections | Capsella bursa-pastoris | In Jordan, [32] Turkey [63], Bulgaria [64], India [65], and Uzbekistan [66]. | The crude extract of C. bursa-pastoris showed antibacterial activity against five Gram-positive and four Gram-negative bacteria. Among them Escherichia coli which is the mainly cause of urinary tract infections [67, 68]. |

C. bursa-pastoris extracts have been reported to exhibit low toxicity in mice, furthermore the plant is contraindicated in case of pregnancy [69], but used as an edible vegetable, eaten raw or cooked in some countries [70, 71]. |

| Ammi visnaga | Italy, Tunisia [72], Palestine [51], Lybia [73], Sudan [74], Egypt [75], Pakistan [76], and Peru [77]. | A. visnaga has antifungal, antibacterial and antiviral activities due the presence of khellin and visnagin [78]. | Overdose or longer use of A. visnaga can lead to queasiness, dizziness, loss of appetite, headache, sleep disorders and it should be avoided during pregnancy [79]. | |

| Ammi majus | Italy, [80] Jordan [81] and Morocco [82]. | The extract of A. majus has shown good inhibition in all the bacterial strains used specially Escherichia coli [83]. | In vitro study on Geese showed severe liver damage in these birds which fed A. majus and exposed to sunlight [84]. | |

| Renal failure | Portulaca oleracea | India [85, 86] and Sri Lanka [87]. | The ethanolic extract of the plant aerial parts showed significant anti-inflammatory and analgesic after intraperitoneal and topical applications but not oral administration when compared with the synthetic drug, diclofenac sodium as the active control [88]. Also its aqueous extract attenuates diabetic nephropathy through inhibition of renal fibrosis and inflammation in mice [89]. Although aqueous and ethanolic extracts of P. oleracea showed potential activity against cisplatin induced acute renal toxicity was studied in rats [90]. |

Due to the huge a mounts of oxalic acid and nitrate in the plant, a high consumption is harmful [91, 92]. |

| Enuresis | Curcuma longa | No reference | No reference | No reference |

| Crocus sativus | No references | No references | Histological studies indicated that saffron has not any toxic effect on liver [93], heart and spleen on mice and rats [94, 95]. | |

| Benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) | Juglans regia | Palestine [96]. | No reference | Juglone compound when isolated from all plant parts has multiple effects on cells such as the reduction of p53 protein levels, induction of DNA damage, inhibition of transcription and induction of cell death [97]. |

| Quercus infectoria | No reference | Contains quercetin which is at 500 mg 2 times daily gave significant symptomatic improvement to most patients, particularly those with negative expressed prostatic secretions cultures [98]. | The aqueous extract of Q. infectoria has significant toxic effect in Wistar rats for over 180 consecutive days of consumption [99]. | |

| Sambucus ebulus | Turkey [100], and Bosnia [101]. | The plant extract produced significant inhibition of edema induced by carrageenan at all doses when compared to the control rats group [102]. | The plant extract showed severe toxicity (in particular severe liver abscess) in all mice at all tested doses [102]. | |

| Zea mays | Algeria, [103] Guatemala [104], Serbia, [105] Cameroon [106], Peru [107], Australia [108], Brazil [109], and Turkey [110]. | Crude ethanolic extract of corn silk (stigma of Zea mays) exhibited a significant activity in anti-inflammatory herbal drugs for TNF (tumor factor-alpha) antagonistic activity. [111]. | No adverse effects have been noticed with the consumption of corn silk which support the safety of corn silk for humans [112]. |

Discussion

In the West Bank area of Palestine, the folk medicine has been trusted and highly appreciated, and many patients go to herbalists or traditional herbal healers to get benefit from this field. In fact, herbal medicine is considered the most used complementary and alternative medicine and this part of complementary and alternative medicines are widely used among patients suffering from urinary tract diseases throughout the world. Most practitioners are males, and this was confirmed in this study; some of them have university degrees.

All over the world, the prevalence of kidney diseases varies significantly from country to country. Epidemiological data on the occurrence of kidney stone was about 12% of global population with a recurrence rate of 70–80% in males and 47–60% in females [29].

According to the use value results, the highest use values for medicinal plants, which were utilized for the treatment of kidney stones, were for Paronychia argentea, Plantago ovata, Punica granatum, Taraxacum syriacum, Morus alba, and Foeniculum vulgare. The highest use values for medicinal plants used for treatment of urinary tract infections were for Capsella bursa-pastoris, Ammi visnaga, and Ammi majus, while the highest use value for plants used for treatment of renal failure was for Portulaca oleracea as well as the highest use values for medicinal plants used for treatment of enuresis were for Curcuma longa and Crocus sativus. Furthermore the maximum use values for plants used for treatment of benign prostate hyperplasia were for Juglans regia, Quercus infectoria, Sambucus ebulus and Zea mays.

Table 5 showed that Paronychia argentea, Punica granatum, Morus alba, and Foeniculum vulgare were used in the folk medicine in many countries for the treatment of kidney stones. The evidence-based effects for this disease were documented for Paronychia argentea, Plantago ovata, Punica granatum, Morus alba, and Foeniculum vulgare, whereas Taraxacum syriacum lacked any evidence-based use for treatment of kidney stone. Moreover, specific attention must be considered during consumption of Paronychia argentea extract, which has a low hemolytic effect.

Regarding the most cited plants which were used for the treatment of urinary tract infections, all of them applied in the folk medicine in many countries and their antibacterial effect approved scientifically, but all of them may have harmful effects due to their adverse reactions and toxicological effect. Mean while the most cited plant for treatment of renal failure was Portulaca oleracea which is used in India and Sri Lanka for the treatment of this disease also, but unfortunately, this plant contains oxalic acid and nitrate. Therefore, high consumption of this plant is harmful to patients suffering from renal failure. Moreover, the most cited plants for treatment of enuresis were Curcuma longa and Crocus sativus which was not mentioned before in any folk or evidence-based medicines for the treatment of this disease and their toxicological effects were not reported.

The most cited plants which were used for the treatment of benign prostate hyperplasia (prostatic enlargement) were; Juglans regia, Sambucus ebulus and Zea mays. These plants had evidence-based studies to be useful for the treatment of this disease, but it is important to keep in mind that Juglans regia, Quercus infectoria and, Sambucus ebulus are harmful as mentioned in the literature review and cannot be used for treatment of any disease.

Over all, there are quite a few phytopharmaceuticals which can be used effectively for the treatment of the urinary tract diseases in the pharmaceutical markets. For that further phytochemical and pharmacological screenings is required to investigate new drugs from the mentioned plants in this study, especially those which have high use values and can be used safely.

Conclusion

The traditional herbal medicine has gradually become more popular, and the need for promoting awareness is perceived. This study showed that traditional herbal medicine is playing a significant role for treatment of urological diseases in the West Bank of Palestine. Based on that, all the plants in this study with high use value should have further phytochemical and pharmacological screenings to test for safety and efficacy. Despite the fact that many of the herbals are currently used by local and international herbalists and traditional healers, serious attention must be given toward many of these products, since they have serious adverse effects and toxicities. Curcuma longa and Crocus sativus were the most cited plants for treatment of enuresis. These plants could be of interest for additional research since they have not been mentioned before in any folk or evidence-based medicines for the treatment of this disease and their toxicological effects were not reported. Also, it is important to keep in mind that Juglans regia, Quercus infectoria and, Sambucus ebulus are harmful and cannot be used for the treatment of any disease.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the herbalists and herbal practitioner healers in the West Bank/ Palestine and all participants in the study.

Authors’ contributions

NJ conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data obtained. This paper was drafted by ANZ, RAl-R, MAA, FH, ZH, MM, MQ and IA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Data are all contained within the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial and/or non-financial competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors gave their consent for the publication of the manuscript for Nidal Jaradat to be the corresponding author.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study aims, protocols and the informed consent forms were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at An-Najah National University (IRB archived number 134/February/2016). All participants agreed to their involvement in our study in our manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- BPH

Benign Prostate Hyperplasia

- CV

Choice Value

- FC

frequency of citation

- Fic

Factor of Informant’s Consensus

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- ns

Total Number of Species

- Nt

Number of Taxa

- Nur

is the number of use

- UV

Use Value

- UVs

Use Values of the Species

Contributor Information

Nidal Amin Jaradat, Email: nidaljaradat@najah.edu.

Abdel Naser Zaid, Email: anzaid@najah.edu.

Rowa Al-Ramahi, Email: rawa_ramahi@najah.edu.

Malik A. Alqub, Email: m.alqub@najah.edu

Fatima Hussein, Email: f.huseen@najah.edu.

Zakaria Hamdan, Email: z.hamdan@najah.edu.

Mahmoud Mustafa, Email: dr_mahmoud681@yahoo.com.

Mohammad Qneibi, Email: mqneibi@najah.edu.

Iyad Ali, Email: iyadali@najah.edu.

References

- 1.Muthu C, Ayyanar M, Raja N, Ignacimuthu S: Medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Kancheepuram District of Tamil Nadu, India J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2006, 2(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Bağcı Y. Ethnobotanical features of Aladağlar (Yahyalı, Kayseri) and its vicinity. Herb J Systc Bot. 2000;7:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabricant DS, Farnsworth NR. The value of plants used in traditional medicine for drug discovery. Electron J Environ Agric Food Chem. 2001;109:69–75. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petri RP, Jr, Delgado RE, McConnell K. Historical and cultural perspectives on integrative medicine. Med Acupunct. 2015;27(5):309–317. doi: 10.1089/acu.2015.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saad B: Integrating traditional Greco-Arab and Islamic diet and herbal medicines in research and clinical practice. In: Phytotherapies: Efficacy, Safety, and Regulation. edn. United States: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2015: 142–182.

- 6.Ali-Shtayeh MS, Jamous RM, Al-Shafie JH, Elgharabah WA, Kherfan FA. Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants used in Palestine (Northern West Bank): a comparative study. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008;4(1):13–19. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaradat NA, Shawahna R, Eid AM, Al-Ramahi R, Asma MK, Zaid AN. Herbal remedies use by breast cancer patients in the West Bank of Palestine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;178:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaradat NA, Ayesh OI, Anderson C. Ethnopharmacological survey about medicinal plants utilized by herbalists and traditional practitioner healers for treatments of diarrhea in the West Bank/Palestine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;182:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali-Shtayeh MS, Jamous RM, Jamous RM. Traditional Arabic Palestinian ethnoveterinary practices in animal health care: a field survey in the West Bank (Palestine) J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;182:35–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaradat N. Ethnopharmacological survey of natural products in palestine. An-Najah Univ J Res (N Sc) 2005;19:14–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alkowni R, Sawalha K. Biotechnology for conservation of palestinian medicinal plants. J Agr Sci Tech. 2012;8(4):1285–1299. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abu-Rabia A. Urinary diseases and ethnobotany among pastoral nomads in the Middle East. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2005;1(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall JE. Guyton and hall textbook of medical physiology. UK: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- 14.Satlin LM, Bockenhauer D. Physiology of the developing kidney: potassium homeostasis and its disorder. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;17:219–246. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-43596-0_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrams P, Chapple C, Khoury S, Roehrborn C, De la Rosette J. Evaluation and treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in older men. J Urol. 2013;189(1):S93–S101. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bitar J. Health annual report Palestine 2014. Palestinian Health Information Center: State of Palestine; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy S, Xu J, Kochanek K, Bastian B. Deaths: final data for. National vital statistics reports: from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System 2016. 2013;64(2):1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali-Shtayeh M, Jamous RM. Red list of threatened plants of the West Bank and Gaza strip and the role of botanic gardens in their conservation. Biodivers Environ Sci. 2002;2:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali-Shtayeh MS, Jamous RM, Al-Shafie JH, Elgharabah WA, Kherfan FA, Qarariah KH, Isra'S K, Soos IM, Musleh AA, Isa BA. Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants used in Palestine (Northern West Bank): a comparative study. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008;4(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans WC. Trease and Evans' pharmacognosy. UK: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009.

- 22.Iwu MM. Handbook of African medicinal plants. United States: CRC press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghazanfar SA. Handbook of Arabian medicinal plants: United States: CRC Press; 1994.

- 24.Dey AK, Rashid MMO, Millat MS, Rashid MM. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by traditional health practitioners and indigenous people in different districts of Chittagong division, Bangladesh. Int J Pharm Sci. 2014;3:01–07. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman B, Gallaher T. Importance indices in ethnobotany. Ethnob Res Appl. 2007;5:201–218. doi: 10.17348/era.5.0.201-218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alzweiri M, Al Sarhan A, Mansi K, Hudaib M, Aburjai T. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal herbs in Jordan, the Northern Badia region. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolson M, Hefler SR, Dall EI, Chaves O, Junior AG, Junior ELC. Ethno-medicinal study of plants used for treatment of human ailments, with residents of the surrounding region of forest fragments of Paraná, Brazil. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;161:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Upadhya V, Hegde HV, Bhat S, Hurkadale PJ, Kholkute S, Hegde G. Ethnomedicinal plants used to treat bone fracture from north-Central western Ghats of India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;142(2):557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiwari A, Soni V, Londhe V, Bhandarkar A, Bandawane D, Nipate S. An overview on potent indigenous herbs for urinary tract infirmity: urolithiasis. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2012;5(1):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeşilada E, Honda G, Sezik E, Tabata M, Goto K, Ikeshiro Y. Traditional medicine in Turkey IV. Folk medicine in the Mediterranean subdivision. J Ethnopharmacol. 1993;39(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(93)90048-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braca A, Bader A, Siciliano T, De Tommasi N. Secondary metabolites from Paronychia Argentea. Magn Reson Chem. 2008;46(1):88–93. doi: 10.1002/mrc.2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aburjai T, Hudaib M, Tayyem R, Yousef M, Qishawi M. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal herbs in Jordan, the Ajloun Heights region. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110(2):294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Said O, Khalil K, Fulder S, Azaizeh H. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal herbs in Israel, the Golan Heights and the West Bank region. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;83(3):251–265. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ali-Shtayeh MS, Yaniv Z, Mahajna J. Ethnobotanical survey in the Palestinian area: a classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73(1):221–232. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benítez G, González-Tejero M, Molero-Mesa J. Pharmaceutical ethnobotany in the western part of Granada province (southern Spain): Ethnopharmacological synthesis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;129(1):87–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salama M. Diuretic plant ecology and medicine in the western Mediterranean coastal region of Egypt. Sciences. 2001;1(4):258–266. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zohra M, Fawzia A. Hemolytic activity of different herbal extracts used in Algeria. Int J Pharm Sci Research. 2014;5:8495–8494. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouanani S, Henchiri C, Migianu-Griffoni E, Aouf N, Lecouvey M. Pharmacological and toxicological effects of Paronychia Argentea in experimental calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;129(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zohra M, Fawzia A. Hemolytic activity of different herbal extracts used in Algeria. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2014;5:8495–8494. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galisteo M, Sánchez M, Vera R, González M, Anguera A, Duarte J, Zarzuelo A. A diet supplemented with husks of Plantago Ovata reduces the development of endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and obesity by affecting adiponectin and TNF-α in obese Zucker rats. J Nutr. 2005;135(10):2399–2404. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.10.2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erum A, Bashir S, Saghir S, Tulain UR, Saleem U, Nasir M, Kanwal F. Hayat malik MN: acute toxicity studies of a novel excipient arabinoxylan isolated from Ispaghula (Plantago Ovata) husk. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2015;38(3):300–305. doi: 10.3109/01480545.2014.956219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ballabh B, Chaurasia O, Ahmed Z, Singh SB. Traditional medicinal plants of cold desert Ladakh—used against kidney and urinary disorders. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;118(2):331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zahid I, Bawazir A, Naser R. Plant based native therapy for the treatment of kidney stones in Aurangabad (MS) J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2013;1(6):189–193. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rani S, Rana J, Jeelani S, Gupta R, Kumari S. Ethnobotanical notes on 30 medicinal polypetalous plants of district Kangra of Himachal Pradesh. J Med Plants Res. 2013;7(20):1362–1369. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Center DWs: Herbal and nutritional treatment of kidney stones. J Am Herb Guild 2012, 10(2):61–71.

- 46.Rathod N, Biswas D, Chitme H, Ratna S, Muchandi I, Chandra R. Anti-urolithiatic effects of Punica Granatum in male rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140(2):234–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tugcu V, Kemahli E, Ozbek E, Arinci YV, Uhri M, Erturkuner P, Metin G, Seckin I, Karaca C, Ipekoglu N. Protective effect of a potent antioxidant, pomegranate juice, in the kidney of rats with nephrolithiasis induced by ethylene glycol. J Endourol. 2008;22(12):2723–2732. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leporatti ML, Ivancheva S. Preliminary comparative analysis of medicinal plants used in the traditional medicine of Bulgaria and Italy. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;87(2):123–142. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gurukar A, Nandini CD, Mahadevamma S, Salimath P. Ocimum sanctum And Morus Alba leaves and Punica Granatum seeds in diet ameliorate diabetes-induced changes in kidney. J Pharm Res. 2012;5(9):4729–4733. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandhu DS, Heinrich M. The use of health foods, spices and other botanicals in the Sikh community in London. Phytother Res. 2005;19(7):633–642. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abu-Rabia A. Herbs as a food and medicine source in Palestine. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2005;6(3):404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maxia A, Lancioni MC, Balia AN, Alborghetti R, Pieroni A, Loi MC. Medical ethnobotany of the Tabarkins, a Northern Italian (Ligurian) minority in south-western Sardinia. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2008;55(6):911–924. doi: 10.1007/s10722-007-9296-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akbulut S, Bayramoglu MM. The trade and use of some medical and aromatic herbs in Turkey. Stud Ethno-Med. 2013;7(2):67–77. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Šarić-Kundalić B, Dobeš C, Klatte-Asselmeyer V, Saukel J. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal use of wild and cultivated plants in middle, south and west Bosnia and Herzegovina. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;131(1):33–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jarić S, Popović Z, Mačukanović-Jocić M, Djurdjević L, Mijatović M, Karadžić B, Mitrović M, Pavlović P: An ethnobotanical study on the usage of wild medicinal herbs from Kopaonik Mountain (Central Serbia). J Ethnopharmacol 2007, 111(1):160–175. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Faridi P, Roozbeh J, Mohagheghzadeh A. Ibn-Sina's life and contributions to medicinal therapies of kidney calculi. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2012;6(5):339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rahimmalek M, Maghsoudi H, Sabzalian M, Ghasemi Pirbalouti A. Variability of essential oil content and composition of different Iranian Fennel (Foeniculum Vulgare Mill.) accessions in relation to some morphological and climatic factors. J Agr Sci Tech. 2014;16(6):1365–3174. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mahmood A, Mahmood A, Malik RN, Shinwari ZK. Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants from Gujranwala district. Pakistan J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;148(2):714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kala CP, Farooquee NA, Majila B. Indigenous knowledge and medicinal plants used by Vaidyas in Uttaranchal. India Nat Prod Radiance. 2005;4(3):195–204. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Macía MJ, Garcia E, Vidaurre PJ. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants commercialized in the markets of La Paz and el alto. Bolivia J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97(2):337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ibrahim FY, El-Khateeb A. Effect of herbal beverages of Foeniculum Vulgare and Cymbopogon Proximus on inhibition of calcium oxalate renal crystals formation in rats. Ann Agric Sci. 2013;58(2):221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shah A, Qureshi S, Ageel A. Toxicity studies in mice of ethanol extracts of Foeniculum Vulgare fruit and Ruta chalepensis aerial parts. J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;34(2–3):167–172. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90034-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cakilcioglu U, Khatun S, Turkoglu I, Hayta S. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants in Maden (Elazig-Turkey) J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137(1):469–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kozuharova E, Lebanova H, Getov I, Benbassat N, Napier J. Descriptive study of contemporary status of the traditional knowledge on medicinal plants in Bulgaria. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2013;7(5):185–198. doi: 10.5897/AJPP12.871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mikawlrawng K, Kumar S. Current scenario of urolithiasis and the use of medicinal plants as antiurolithiatic agents in Manipur (north East India): a review. Int J Herb Med. 2014;2(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Egamberdieva D, Mamadalieva N, Khodjimatov O, Tiezzi A. Medicinal plants from Chatkal biosphere reserve used for folk medicine in Uzbekistan. Med Aromat Plant Sci Biotechnol. 2012;7(1):56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grosso C, Vinholes J, Silva LR. Pinho PGd, Gonçalves RF, Valentão P, Jäger AK, Andrade PB: chemical composition and biological screening of Capsella Bursa-Pastoris. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2011;21(4):635–643. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2011005000107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Choi WJ, Kim SK, Park HK, Sohn UD, Kim W. Anti-inflammatory and anti-superbacterial properties of sulforaphane from Shepherd's purse. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;18(1):33–39. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al-Snafi AE. The chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Capsella Bursa-Pastoris-a review. Int J Pharm Sci Res Tox. 2015;5(2):76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zennie TM, Ogzewalla D. Ascorbic acid and vitamin a content of edible wild plants of Ohio and Kentucky. Econ Bot. 1977;31(1):76–79. doi: 10.1007/BF02860657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kweon M-H, Kwak J-H, Ra K-S, Sung H-C, Yang H-C. Structural characterization of a flavonoid compound scavenging superoxide anion radical isolated from Capsella Bursa-Pastoris. BMB Rep. 1996;29(5):423–428. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leporatti ML, Ghedira K. Comparative analysis of medicinal plants used in traditional medicine in Italy and Tunisia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2009;5(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.El-Mokasabi F. The state of the art of traditional herbal medicine in the eastern mediterranean coastal region of Libya. Middle East J Sci Res. 2014;21(4):575–582. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khalid H, Abdalla WE, Abdelgadir H, Opatz T, Efferth T. Gems from traditional north-African medicine: medicinal and aromatic plants from Sudan. Nat prod bioprospect. 2012;2(3):92–103. doi: 10.1007/s13659-012-0015-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.El-Seedi HR, Burman R, Mansour A, Turki Z, Boulos L, Gullbo J, Göransson U. The traditional medical uses and cytotoxic activities of sixty-one Egyptian plants: discovery of an active cardiac glycoside from Urginea maritima. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;145(3):746–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jan S, Khan K, Hameed I, Ahmad N. Ethnobotanical studies of the medicinal plants of Malakand agency, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Pakistan s. 2012;18(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bussmann RW, Ashley G, Sharon D, Chait G, Diaz D, Pourmand K, Jonat B, Somogy S, Guardado G, Aguirre C. Proving that traditional knowledge works: the antibacterial activity of Northern Peruvian medicinal plants. Ethnob Res Appl. 2011;9:067–096. doi: 10.17348/era.9.0.67-96. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hudson J, Towers GN. Phytomedicines as antivirals. Drugs Future. 1999;24(3):295–301. doi: 10.1358/dof.1999.024.03.858620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hashim S, Jan A, Marwat KB, Khan MA. Phytochemistry and medicinal properties of Ammi Visnaga (Apiacae) Pak J Bot. 2014;46(3):861–867. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leporatti ML, Guarrera PM. Ethnobotanical remarks in Capitanata and Salento areas (Puglia, southern Italy) Etnobiología. 2015;5(1):51–64. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lev E, Amar Z. Ethnopharmacological survey of traditional drugs sold in the Kingdom of Jordan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;82(2):131–145. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rhattas M, Douira A, Zidane L. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Talassemtane Nationall Park (western Rif of Morocco) J Appl Biosci. 2016;97:9187–9211. doi: 10.4314/jab.v97i1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Al Akeel R, Al-Sheikh Y, Mateen A, Syed R, Janardhan K, Gupta V. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of crude protein extracts from seeds of six different medical plants against standard bacterial strains. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2014;21(2):147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Egyed M, Malkinson M, Shlosberg A. Observations on the experimental poisoning of young geese with Ammi Majus. Avian Pathol. 1974;3(2):79–87. doi: 10.1080/03079457409353821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Khare C. Indian medicinal plants. 1. Berlin/Heidlburg: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sharma H, Kumar RA. Health security in ethnic communities through nutraceutical leafy vegetables. J Environ Res Develop. 2013;7(4):1423–1431. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sultana A, Rahman K: Portulaca oleracea Linn. A global panacea with ethno-medicinal and pharmacological potential. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 2013, 5:33–39.

- 88.Chan K, Islam M, Kamil M, Radhakrishnan R, Zakaria M, Habibullah M, Attas A. The analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of Portulaca Oleracea L. subsp. sativa (haw.) Celak. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73(3):445–451. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee AS, Lee YJ, Lee SM, Yoon JJ, Kim JS, Kang DG, Lee HS. An aqueous extract of Portulaca Oleracea ameliorates diabetic nephropathy through suppression of renal fibrosis and inflammation in diabetic db/db mice. Am J Chin Med. 2012;40(03):495–510. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X12500383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Karimi G, Khoei A, Omidi A, Kalantari M, Babaei J, Taghiabadi E, Razavi BM. Protective effect of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Portulaca Oleracea against cisplatin induced nephrotoxicity. Iranian J Basic Med Sci. 2010;13(2):31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Guil J, Rodríguez-Garcí I, Torija E. Nutritional and toxic factors in selected wild edible plants. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1997;51(2):99–107. doi: 10.1023/A:1007988815888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fontana E, Hoeberechts J, Nicola S, Cros V, Battista Palmegiano G, Giorgio Peiretti P. Nitrogen concentration and nitrate/ammonium ratio affect yield and change the oxalic acid concentration and fatty acid profile of purslane (Portulaca Oleracea L.) grown in a soilless culture system. J Sci Food Agr. 2006;86(14):2417–2424. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bahmani M, Rafieian M, Baradaran A, Rafieian S, Rafieian-kopaei M. Nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity evaluation of Crocus Sativus stigmas in neonates of nursing mice. J Nephropathol. 2014;3(2):81–91. doi: 10.12860/jnp.2014.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.HosseinZadeh H, Sadeghi Shakib S, Khadem Sameni A, Taghiabadi E. Acute and subacute toxicity of safranal, a constituent of saffron, in mice and rats. Iranian J Pharm Res. 2013;12(1):93–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ramadan A, Soliman G, Mahmoud SS, Nofal SM, Abdel-Rahman RF. Evaluation of the safety and antioxidant activities of Crocus Sativus and Propolis ethanolic extracts. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2012;16(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jscs.2010.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Saad B, Azaizeh H, Said O. Botanical Medicine in Clinical Practice. UK: CABI; 2008.

- 97.Paulsen MT, Ljungman M. The natural toxin juglone causes degradation of p53 and induces rapid H2AX phosphorylation and cell death in human fibroblasts. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;209(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shoskes D. Use of the bioflavonoid quercetin in patients with longstanding chronic prostatitis. J Am Neutraceutical Assoc. 1999;2:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Iminjan M, Amat N, Li X-H, Upur H, Ahmat D, He B. Investigation into the toxicity of traditional Uyghur medicine Quercus Infectoria galls water extract. PLoS One. 2014;9(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Genç GE, Özhatay N: An ethnobotanical study in Catalca (European part of Istanbul) Turkish J PharmSci 2006, 3(2):73–89.

- 101.Redzic S. Wild medicinal plants and their usage in traditional human therapy (southern Bosnia and Herzegovina, W. Balkan) J Medl Plants Res. 2010;4(11):1003–1027. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ebrahimzadeh MA, Mahmoudi M, Karami M, Saeedi S, Ahmadi AH, Salimi E. Separation of active and toxic portions in Sambucus Ebulus. Pak J Biol Sci. 2007;10(22):4171–4173. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.4171.4173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sekkoum K, Cheriti A, Taleb S, Bourmita Y, Belboukhari N. Traditional phytotherapy for urinary diseases in Bechar district (south west of Algeria) Electron J Environ Agric Food Chem. 2011;10(8):2616–2622. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cáceres A, Girón LM, Martínez AM. Diuretic activity of plants used for the treatment of urinary ailments in Guatemala. J Ethnopharmacol. 1987;19(3):233–245. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(87)90001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Maksimović Z, Malenčić Đ, Kovačević N. Polyphenol contents and antioxidant activity of Maydis stigma extracts. Bioresour Technol. 2005;96(8):873–877. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Noumi E, Bouopda N. A review of prostate diseases at yaounde: epidemiology, prophylaxy and phytotherapy. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2014;13(1):36–46. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Monigatti M, Bussmann RW, Weckerle CS. Medicinal plant use in two Andean communities located at different altitudes in the Bolívar Province. Peru J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;145(2):450–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wojcikowski K, Wohlmuth H, Johnson DW, Rolfe M, Gobe G. An in vitro investigation of herbs traditionally used for kidney and urinary system disorders: potential therapeutic and toxic effects. Nephrology. 2009;14(1):70–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kuhnen S, Bernardi Ogliari J, Dias PF, da Silva SM, Ferreira AG, Bonham CC, Wood KV, Maraschin M. Metabolic fingerprint of Brazilian maize landraces silk (stigma/styles) using NMR spectroscopy and chemometric methods. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58(4):2194–2200. doi: 10.1021/jf9037776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sağıroğlu M, Dalgıç S, Toksoy S. Medicinal plants used in Dalaman (Muğla) Turkey J Med Plant Res. 2013;7(28):2053–2066. doi: 10.5897/JMPR2013.2590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Habtemariam S. Extract of corn silk (stigma of Zea Mays) inhibits the tumour necrosis factor-alpha-and bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced cell adhesion and ICAM-1 expression. Planta Med. 1998;64(4):314–318. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang C, Zhang T, Liu J, Lu S, Zhang C, Wang E, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Liu J. Subchronic toxicity study of corn silk with rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137(1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are all contained within the article.