Abstract

AIM

To investigate whether the preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) could predict the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients with portal/hepatic vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT/HVTT) after hepatectomy.

METHODS

The study population included 81 HCC patients who underwent hepatectomy and were diagnosed with PVTT/HVTT based on pathological examination. The demographics, laboratory analyses, and histopathology data were analyzed.

RESULTS

Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were determined in the patients with a high (> 2.9) and low (≤ 2.9) NLR. The median OS and DFS duration in the high NLR group were significantly shorter than those in the low NLR group (OS: 6.2 mo vs 15.7 mo, respectively, P = 0.007; DFS: 2.2 mo vs 3.7 mo, respectively, P = 0.039). An NLR > 2.9 was identified as an independent predictor of a poor prognosis of OS (P = 0.034, HR = 1.866; 95%CI: 1.048-3.322) in uni- and multivariate analyses. Moreover, there was a significantly positive correlation between the NLR and the Child-Pugh score (r = 0.276, P = 0.015) and the maximum diameter of the tumor (r = 0.435, P < 0.001). Additionally, the NLR could enhance the prognostic predictive power of the CLIP score for DFS in these patients.

CONCLUSION

The preoperative NLR is a prognostic predictor after hepatectomy for HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT. NLR > 2.9 indicates poorer OS and DFS.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Portal/hepatic vein tumor thrombosis, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, Prognosis

Core tip: The systemic inflammatory response generated by tumors has been shown to cause the upregulation of cytokines and inflammatory mediators, leading to the promotion of angiogenesis and DNA damage and the inhibition of apoptosis. The presence of a systemic inflammatory response can be detected by the elevation of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), which has been shown to be associated with poorer prognosis in patients with various types of malignant tumors. Our findings confirm that the NLR can be used as a potential prognostic predictor for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with portal/hepatic vein tumor thrombosis after resection. The results of the present study may help identify a new serum marker for predicting the post-operation survival of these patients.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignant tumors worldwide[1]. Portal/hepatic vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT/HVTT) is a common complication of HCC[2] and is widely accepted as a sign of advanced stage[3]. PVTT/HVTT frequently leads to intrahepatic or distant metastasis with a poor prognosis[4]. The median survival of untreated HCC with PVTT/HVTT has been reported to be 2.7 mo, whereas the survival in those without PVTT/HVTT has been reported to be 24.4 mo[5,6]. A large body of evidence has shown that surgery can improve the survival of HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT[7-9]. However, the median survival duration varies from 9.0 to 26.0 mo[7-9], which is still unsatisfactory. The reasons for this remain unclear and seem to be complex and multifactorial.

The systemic inflammatory response generated by tumors has been shown to cause the upregulation of cytokines and inflammatory mediators, leading to the promotion of angiogenesis, DNA damage, and inhibition of apoptosis[10-12]. The presence of a systemic inflammatory response can be detected by the elevation of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), which has been shown to be associated with poorer prognosis in patients with various types of malignant tumors, including colorectal cancer, intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, gastric cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, breast cancer, and soft tissue sarcoma[13-18]. Recently, an increasing number of reports has shown that the NLR can be used as a predictor of poor survival after curative hepatectomy, radio-frequency ablation (RFA), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), liver transplantation (LT), and sorafenib therapy for HCC[19-29]. To date, however, few studies have mentioned the role of the NLR in predicting the prognosis of HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT after hepatectomy.

The current study aimed to evaluate the relationship between systemic inflammation, as represented by the preoperative NLR, and long-term outcomes in HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT after hepatectomy, determining whether the NLR can be used as a predictor of survival in these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection and operative techniques

The present study population included 81 HCC patients who underwent hepatectomy at the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Cancer Center of Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China and were diagnosed with PVTT/HVTT via pathological examination between January 2004 and July 2009. During this period, there were 931 hepatocellular carcinoma patients who underwent hepatic resection at our department.

The patients were excluded from the analysis if they had extrahepatic disease, thrombus extending to the level of the superior mesenteric vein, or any antitumor treatments before operation.

The preoperative diagnosis and tumor evaluation were made using ultrasonography, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR), and/or tri-phase contrast-enhanced helical computed tomography (CT). Liver function was evaluated based on the Child-Pugh classification system[30] and/or the indocyanine green (ICG) clearance test performed routinely before operation. The neutrophil and lymphocyte counts were routinely measured within three days before operation. NLR was calculated by dividing the neutrophil measurement by the lymphocyte measurement.

The selection criteria for the operative procedure depended on the tumor location and extent, liver function, and future liver remnant volume. Hepatectomy was defined as major if three or more Couinaud segments were resected and minor if fewer than three segments were resected[31]. The diagnosis of HCC and PVTT/HVTT was confirmed by histopathological examination of the resected specimens.

Postoperative care and follow-up

Operative mortality was defined as death within 30 d after operation. Operative complication was defined as any deviation from the normal course of recovery with the need for any medical interventions.

All patients were followed up as a routine protocol one month after operation by enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen, serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) examination, and serum examination of liver function. Then, follow-up was carried out every 2-3 mo with enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen or combined CDUS and chest X-ray; and serum examination for the first year. Thereafter, all patients were followed up every 3-6 mo with CDUS, chest X-ray, and serum tests. Abdominal enhanced CT, abdominal enhanced MR, and/or contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) were performed when intrahepatic recurrence was suspected, and thoracic enhanced CT, whole-body bone scintigraphy, or/and other relevant radiological examination was performed when extrahepatic recurrence was suspected.

Patients with recurrence were treated with the following therapies based on their liver function and pattern of recurrence as a routine practice: hepatectomy, TACE, transarterial infusion (TAI), percutaneous microwave tumor coagulation therapy, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), systemic chemotherapy, percutaneous ethanol injection therapy (PEI), sealed source radiotherapy, sorafenib therapy, cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cell therapy, and/or supportive care.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between categorical variables were performed using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t test (when values were normally distributed) or the Mann-Whitney test (when the values had a distribution that departed significantly from normal). Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and comparison were made using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses using Cox’s proportional hazard models were performed to evaluate the prognostic factors. The correlation between two variables was examined by Pearson’s correlation analysis (when the variables were normally distributed) or Spearman’s correlation analysis (when the variables had a distribution that departed significantly from normal). A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software for Windows (ver. 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

All continuous variable data were expressed as mean ± standard error (when the values were normally distributed) or medians (range) (when the values had a distribution that departed significantly from normal). All data regarding categorical variables are shown as n (proportion).

RESULTS

Correlation between NLR and postoperative survival

To determine whether an elevated NLR was correlated with the postoperative survival of HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT, we performed survival analysis, and the results are shown in Table 1. Using NLR cut-offs from 1 to 5 and comparing the 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS) rates, several NLRs were found statistically correlated with the postoperative OS of HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT. Among these, an NLR of 2.9 was the most significant, with a χ2 value of 7.227 and a P value of 0.007. We therefore utilized an NLR cut-off of 2.9 as a risk factor of the poorer prognosis of these patients.

Table 1.

Correlation between each neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio cut-off and overall survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with portal/hepatic vein tumor thrombosis using the Kaplan-Meier method

| Cut-off value | Group | Cases | 1-yr OS | 2-yr OS | 3-yr OS | 5-yr OS | χ2 | P value |

| 1.0 | NLR ≤ 1 vs > 1 | 5 vs 76 | 80.0% vs 46.9% | 40.0% vs 27.7% | 40.0% vs 19.0% | 0.0% vs 17.3% | 0.272 | 0.602 |

| 1.5 | NLR ≤ 1.5 vs > 1.5 | 16 vs 65 | 80.0% vs 41.5% | 46.7% vs 24.2% | 26.7% vs 19.8% | 6.7% vs 19.8% | 1.575 | 0.210 |

| 2.0 | NLR ≤ 2 vs > 2 | 28 vs 53 | 72.3% vs 37.3% | 44.2% vs 20.7% | 28.1% vs 17.8% | 16.1% vs 17.8% | 3.657 | 0.056 |

| 2.5 | NLR ≤ 2.5 vs > 2.5 | 39 vs 42 | 64.5% vs 35.1% | 39.2% vs 18.9% | 25.2% vs 18.9% | 16.8% vs 18.9% | 3.935 | 0.047 |

| 2.6 | NLR ≤ 2.6 vs > 2.6 | 42 vs 39 | 62.1% vs 35.4% | 38.5% vs 17.7% | 24.7% vs 17.7% | 16.5% vs 17.7% | 3.987 | 0.046 |

| 2.7 | NLR ≤ 2.7 vs > 2.7 | 44 vs 37 | 59.1% vs 37.3% | 36.6% vs 18.7% | 23.6% vs 18.7% | 15.7% vs 18.7% | 2.254 | 0.133 |

| 2.8 | NLR ≤ 2.8 vs > 2.8 | 49 vs 32 | 60.2% vs 32.7% | 39.1% vs 13.1% | 26.1% vs 13.1% | 18.3% vs 13.1% | 6.007 | 0.014 |

| 2.9 | NLR ≤ 2.9 vs > 2.9 | 51 vs 30 | 59.8% vs 31.5% | 39.5% vs 10.5% | 26.3% vs 10.5% | 18.4% vs 10.5% | 7.227 | 0.007 |

| 3.0 | NLR ≤ 3 vs > 3 | 53 vs 28 | 59.8% vs 32.1% | 38.8% vs 10.7% | 25.9% vs 10.7% | 18.1% vs 10.7% | 6.158 | 0.013 |

| 3.5 | NLR ≤ 3.5 vs > 3.5 | 62 vs 19 | 56.7% vs 26.3% | 34.4% vs 10.5% | 23.7% vs 10.5% | 17.2% vs 10.5% | 2.843 | 0.092 |

| 4.0 | NLR ≤ 4 vs > 4 | 66 vs 15 | 56.2% vs 20.0% | 33.8% vs 6.7% | 23.9% vs 6.7% | 17.9% vs 6.7% | 5.284 | 0.022 |

| 4.5 | NLR ≤ 4.5 vs > 4.5 | 72 vs 9 | 51.1% vs 33.3% | 30.7% vs 11.1% | 21.7% vs 11.1% | 16.3% vs 11.1% | 1.724 | 0.189 |

| 5.0 | NLR ≤ 5 vs > 5 | 75 vs 6 | 50.3% vs 33.3% | 29.4% vs 16.7% | 20.7% vs 16.7% | 15.6% vs 16.7% | 0.527 | 0.468 |

Clinicopathological characteristics

The characteristics of the 81 HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT are summarized in Table 2. Of the 81 patients, 51 had an NLR ≤ 2.9 and 30 had an NLR > 2.9. Most of the characteristics of the two groups were similar. Patients in the high-NLR group had significantly higher preoperative HBV DNA (P = 0.025), serum AFP level (P = 0.038), and maximum diameter of tumor (P = 0.003), worse Child-Pugh score (P = 0.017), longer operative time (P = 0.011), and shorter surgical margin (P = 0.002).

Table 2.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the 81 hepatocellular carcinoma patients with portal/hepatic vein tumor thrombosis, n (%)

| NLR ≤ 2.9 (n = 51) | NLR > 2.9 (n = 30) | P value | |

| Age in years | 48.49 ± 1.52 | 48.47 ± 2.28 | 0.993 |

| Gender | 0.292 | ||

| Male | 48 (94.1) | 30 (100.0) | |

| Female | 3 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| HBsAg status | 0.281 | ||

| Negative | 3 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Positive | 45 (88.2) | 30 (100.0) | |

| Unknown | 3 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Preoperative HBV DNA | 0.025 | ||

| < 1 × 103 | 19 (37.3) | 4 (13.3) | |

| ≥ 1 × 103 | 23 (45.1) | 19 (63.3) | |

| Unknown | 9 (17.6) | 7 (23.3) | |

| Preoperative AFP level | 0.038 | ||

| < 400 ng/mL | 19 (37.3) | 5 (16.7) | |

| ≥ 400 ng/mL | 30 (58.8) | 25 (83.3) | |

| Unknown | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Preoperative ALT level (U/L) | 41 (10-713) | 42.5 (21-146.5) | 0.697 |

| Preoperative Hgb level (g/L) | 147.79 ± 2.43 | 148.52 ± 4.37 | 0.884 |

| Preoperative PLT level (109/L) | 185.84 ± 12.73 | 201.97 ± 13.97 | 0.417 |

| Preoperative Child-Pugh score | 0.017 | ||

| Child A (5) | 21 (41.2) | 7 (23.3) | |

| Child A (6) | 22 (43.1) | 14 (46.7) | |

| Child B (7) | 4 (7.8) | 5 (16.7) | |

| Child B (8) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Child B (9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Unknown | 3 (5.9) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Preoperative ICGR15 (%) | 6.42 ± 0.79 | 5.37 ± 0.94 | 0.404 |

| Number of tumors | 0.474 | ||

| Solitary | 28 (54.9) | 14 (46.7) | |

| Multiple | 23 (45.1) | 16 (53.3) | |

| Maximum diameter of tumor (cm) | 8.93 ± 0.58 | 11.88 ± 0.80 | 0.003 |

| Uni/bilobular disease | 0.414 | ||

| Unilobular disease | 48 (94.1) | 26 (86.7) | |

| Bilobular disease | 3 (5.9) | 4 (13.3) | |

| Adjacent organ invasion | 0.722 | ||

| Negative | 32 (62.7) | 20 (66.7) | |

| Positive | 19 (37.3) | 10 (33.3) | |

| Operative procedure | 0.215 | ||

| Minor | 45 (88.2) | 23 (76.7) | |

| Major | 6 (11.8) | 7 (23.3) | |

| Total occlusion time of the hepatic inflow (min) | 17.89 ± 1.58 | 18.18 ± 2.53 | 0.918 |

| Total operative time (min) | 168.43 ± 7.19 | 205.00 ± 13.77 | 0.011 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 579.41 ± 61.82 | 891.67 ± 171.61 | 0.095 |

| Blood transfusion (mL) | 0.061 | ||

| No | 33 (64.7) | 13 (43.3) | |

| Yes | 18 (35.3) | 17 (56.7) | |

| Surgical margin | 0.002 | ||

| ≤ 1 cm | 33 (64.7) | 25 (83.3) | |

| > 1 cm | 18 (35.3) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 4 (13.3) | |

| Histological grade of tumor cells | 0.958 | ||

| I-II | 19 (37.3) | 11 (36.7) | |

| III-IV | 32 (62.7) | 19 (63.3) | |

| Postoperative complication | 0.792 | ||

| Negative | 42 (82.4) | 24 (80.0) | |

| Positive | 9 (17.6) | 6 (20.0) | |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 11 (8-28) | 11.5 (8-83) | 0.468 |

NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Recurrence patterns and treatments

The patterns of recurrence and postoperative treatments in the patients of the two groups are shown in Table 3. The recurrence patterns were not significantly different between the two groups.

Table 3.

Patterns of recurrence and postoperative treatments in the patients of the two groups, n (%)

| NLR ≤ 2.9 | NLR > 2.9 | P value | |

| Recurrence | n = 51 | n = 30 | 1.000 |

| Negative | 3 (5.9) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Positive | 39 (76.5) | 23 (76.7) | |

| Unknown | 9 (17.6) | 6 (20) | |

| Recurrence pattern | n = 39 | n = 23 | 0.832 |

| Intrahepatic only | 26 (66.7) | 15 (65.2) | |

| Extrahepatic only | 2 (5.1) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Both | 11 (28.2) | 6 (26.1) | |

| Treatments | n = 51 | n = 30 | |

| TACE | 23 | 15 | |

| Hepatectomy | 2 | 0 | |

| PMCT | 4 | 0 | |

| Systemic chemotherapy | 3 | 2 | |

| RFA | 5 | 0 | |

| PEI | 2 | 0 | |

| CIK | 0 | 2 | |

| TAI | 1 | 1 | |

| Sorafenib | 0 | 1 | |

| Radiotherapy | 1 | 0 | |

| Sealed source radiotherapy | 1 | 2 | |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | 4 | 0 | |

| Supportive care only | 21 | 12 |

Some patients accepted more than one type of treatment. NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization; PMCT: Percutaneous microwave tumor coagulation therapy.

Survival analysis

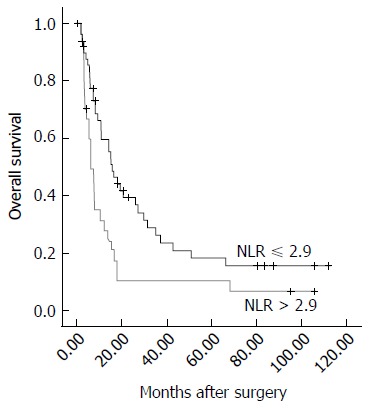

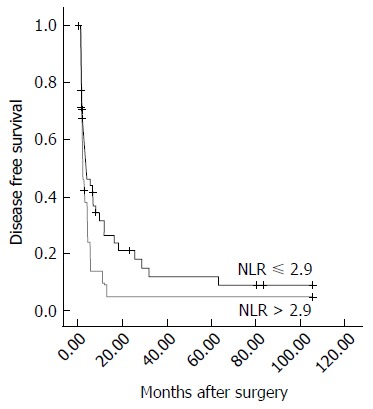

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, when we compared the survival outcomes in the two groups, we found that the 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were significantly lower in the high (31.5%, 10.5%, 10.5%, and 10.5%, respectively) than in the low (59.8%, 39.5%, 26.3%, and 18.4%, respectively) NLR group (P = 0.007). Similarly, we found that the 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rates were significantly lower in the high (9.4%, 4.7%, 4.7%, and 4.7%, respectively) than in the low (29.1%, 21.1%, 12.1%, and 9.1%, respectively) NLR group (P = 0.039).

Figure 1.

Overall survival of patients in the two groups. The median overall survival duration in the high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) group was significantly shorter tháan that in the low NLR group (6.2 mo vs 15.7 mo, respectively, P = 0.007).

Figure 2.

Disease-free survival of patients in the two groups. The median disease-free survival duration in the high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) group was significantly shorter than that in the low NLR group (2.2 mo vs 3.7 mo, respectively, P = 0.039).

Prognostic factors for the overall survival of HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the factors affecting OS are shown in Table 4. An NLR > 2.9, AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL, multiple tumors, bilobular disease, and surgical margin ≤ 1 cm found to be significant on univariate analysis were then included in multivariate regression analysis, and the results revealed that an NLR > 2.9 [P = 0.034, a hazard ratio (HR): 1.866; 95%CI: 1.048-3.322], AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL (P = 0.042, HR = 1.863; 95%CI: 1.024-3.392), and bilobular disease (P = 0.019, HR = 3.292; 95%CI: 1.215-8.918) were independent predictors of the poorer prognosis of OS.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors affecting overall survival

| Variables |

Univariate analysis for OS |

Multivariate analysis for OS |

||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| NLR > 2.9 | 1.969 | 1.190-3.259 | 0.008 | 1.866 | 1.048-3.322 | 0.034 |

| Age ≤ 50 yr | 1.532 | 0.913-2.569 | 0.106 | |||

| Female | 2.035 | 0.625-6.623 | 0.238 | |||

| HBsAg (+) | 1.055 | 0.327-3.402 | 0.929 | |||

| HBV-DNA > 1 × 103 | 1.258 | 0.709-2.234 | 0.432 | |||

| AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL | 2.026 | 1.163-3.527 | 0.013 | 1.863 | 1.024-3.392 | 0.042 |

| ALT ≤ 40 U/L | 1.122 | 0.684-1.839 | 0.649 | |||

| Hgb > 130 g/L | 1.964 | 0.987-3.909 | 0.054 | |||

| PLT > 100 × 109/L | 1.168 | 0.467-2.916 | 0.740 | |||

| Child A | 1.090 | 0.564-2.106 | 0.798 | |||

| ICGR15 ≤ 10% | 1.642 | 0.746-3.610 | 0.218 | |||

| Multiple tumors | 1.676 | 1.022-2.748 | 0.041 | 1.084 | 0.627-1.876 | 0.772 |

| Maximum diameter of tumor > 5 cm | 1.869 | 0.973-3.593 | 0.061 | |||

| Bilobular disease | 2.764 | 1.153-6.628 | 0.023 | 3.292 | 1.215-8.918 | 0.019 |

| Adjacent organ invaded | 1.268 | 0.756-2.127 | 0.369 | |||

| Major hepatectomy | 1.145 | 0.597-2.195 | 0.683 | |||

| Pringle maneuver | 1.937 | 0.950-3.952 | 0.069 | |||

| Operation time > 180 min | 1.352 | 0.819-2.233 | 0.238 | |||

| Intraoperative blood loss > 1000 mL | 1.721 | 0.957-3.096 | 0.070 | |||

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 1.485 | 0.901-2.448 | 0.121 | |||

| Surgical margin ≤ 1 cm | 1.868 | 1.024-3.408 | 0.042 | 1.195 | 0.596-2.394 | 0.616 |

| Histologic grade III-IV | 1.220 | 0.736-2.020 | 0.440 | |||

| Postoperative complication | 1.467 | 0.807-2.667 | 0.209 | |||

| Postoperative hospital stay ≤ 10 d | 1.078 | 0.646-1.798 | 0.774 | |||

NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; OS: Overall survival; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; AFP: Alpha fetoprotein; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; PLT: Platelet.

Prognostic factors for the disease-free survival of HCC with portal/hepatic vein tumor thrombosis

Similarly, univariate and multivariate analyses of the factors affecting DFS are shown in Table 5. NLR > 2.9, AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL, Hgb > 130 g/L, ICGR15 ≤ 10%, and intraoperative blood loss > 1000 mL were found to be significant on univariate analysis and were then included in multivariate regression analysis. However, none was identified as an independent predictor of the poorer prognosis of DFS.

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors affecting disease-free survival

| Variables |

Univariate analysis for DFS |

Multivariate analysis for DFS |

||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| NLR > 2.9 | 1.720 | 1.017-2.907 | 0.043 | 1.553 | 0.850-2.837 | 0.153 |

| Age ≤ 50 yr | 1.424 | 0.842-2.409 | 0.188 | |||

| Female | 1.593 | 0.384-6.610 | 0.522 | |||

| HBsAg (+) | 1.314 | 0.407-4.249 | 0.648 | |||

| HBV-DNA > 1 × 103 | 1.426 | 0.772-2.634 | 0.257 | |||

| AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL | 2.099 | 1.196-3.684 | 0.010 | 1.732 | 0.954-3.146 | 0.071 |

| ALT ≤ 40 U/L | 1.272 | 0.771-2.098 | 0.346 | |||

| Hgb > 130 g/L | 2.629 | 1.266-5.460 | 0.010 | 2.051 | 0.940-4.476 | 0.071 |

| PLT ≤ 100 × 109/L | 1.147 | 0.413-3.186 | 0.793 | |||

| Child B | 1.254 | 0.631-2.492 | 0.518 | |||

| ICGR15 ≤ 10% | 2.470 | 1.052-5.796 | 0.038 | 2.134 | 0.870-5.236 | 0.098 |

| Multiple tumors | 1.189 | 0.709-1.992 | 0.512 | |||

| Maximum diameter of tumor > 5 cm | 1.865 | 0.944-3.686 | 0.073 | |||

| Bilobular disease | 1.778 | 0.753-4.199 | 0.189 | |||

| Adjacent organ not invaded | 1.119 | 0.659-1.899 | 0.677 | |||

| Major hepatectomy | 1.253 | 0.635-2.474 | 0.516 | |||

| Pringle maneuver | 1.922 | 0.933-3.960 | 0.076 | |||

| Operation time ≤ 180 min | 1.067 | 0.638-1.785 | 0.805 | |||

| Intraoperative blood loss > 1000 mL | 1.854 | 1.012-3.396 | 0.046 | 1.258 | 0.649-2.437 | 0.497 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 1.655 | 0.972-2.817 | 0.064 | |||

| Surgical margin ≤ 1 cm | 1.492 | 0.827-2.690 | 0.183 | |||

| Histologic grade I-II | 1.083 | 0.648-1.808 | 0.761 | |||

| Postoperative complication | 1.173 | 0.608-2.264 | 0.634 | |||

| Postoperative hospital stay > 10 d | 1.041 | 0.616-1.759 | 0.882 | |||

NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; DFS: Disease-free survival; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; AFP: Alpha fetoprotein; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; PLT: Platelet.

Correlation between NLR and clinical factors

The relationship between the NLR and Child-Pugh score, preoperative AFP level, preoperative HBV DNA level, and maximum tumor diameter, which may impact the prognosis of HCC patients, was evaluated. There was a significantly positive correlation between the NLR and Child-Pugh score (r = 0.276, P = 0.015). Additionally, the NLR had a significantly positive correlation with the maximum tumor diameter (r = 0.435, P < 0.001). NLR was not associated with the preoperative AFP level and HBV DNA level (data not shown).

NLR can enhance the prognostic predictive power of the CLIP score for DFS in HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT

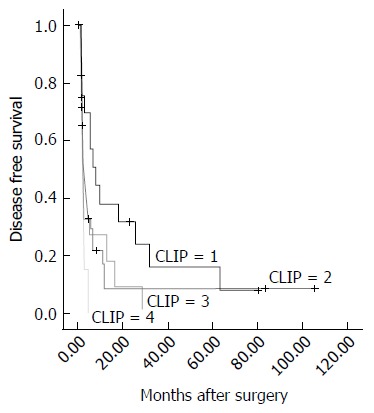

The Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) score was calculated as described previously[32] in 76 of the 81 cases (the score could not be calculated in 5 cases due to missing data). The CLIP stages assigned in the present study population ranged from 1 to 4 because all of the cases enrolled in the current study population had PVTT/HVTT. Survival analysis revealed significant differences in DFS (χ2 = 7.870, P = 0.049) for each group, as shown in Figure 3. However, the result was opposite for OS (P = 0.055, data not shown).

Figure 3.

Disease-free survival of patients in the four groups according to the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program score. The median disease-free survival duration in each group was 7.9, 2.3, 1.5, and 2.3 mo, respectively (from 1 to 4, P = 0.039). CLIP: Cancer of the Liver Italian Program.

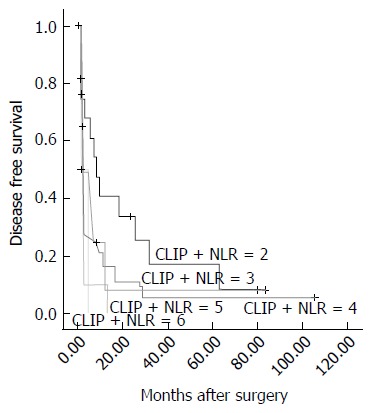

We added the NLR to the CLIP score in accordance with the following scheme: a low NLR (NLR ≤ 2.9) was given a score of 1, and a high NLR (NLR > 2.9) was given a score of 2. Next, all of the cases were divided into 5 groups (from 2 to 6). Survival analysis revealed significant differences in DFS (χ2 = 11.371, P = 0.023) for the 5 groups, as shown in Figure 4. A larger χ2 value and a smaller P value suggested the NLR could enhance the prognostic predictive power of the CLIP score for DFS in these patients. Similarly, based on the results using CLIP score alone, there was no significant difference in OS (P = 0.055, data not shown).

Figure 4.

Disease-free survival of patients in the four groups according to the combined neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio with Cancer of the Liver Italian Program score. The median disease-free survival duration in each group was 7.9, 2.3, 2.7, 1.6, and 1.1 mo, respectively (from 2 to 6, P = 0.023). CLIP: Cancer of the Liver Italian Program; NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

DISCUSSION

NLR, a simple, cheap, safe and effective marker of inflammation, is easily calculated from routinely available data. Many studies have shown that a higher NLR is correlated with adverse survival outcomes in patients with various tumors[13-15]. NLR was first linked to hepatic malignant tumors by Halazun et al[22,33]. They observed poor DFS and OS in patients with colorectal liver metastasis and a higher preoperative NLR, with the NLR being an independent predictor of both recurrence and death[33]. Recently, increasing reports have shown that NLR can be used as a predictor of poor survival after various types of treatments for HCC[19-29,34,35]. To expand these findings, we assessed whether NLR can evaluate the prognosis of HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT after hepatectomy. Moreover, we investigated the best cut-off value for the NLR in prediction of prognosis for these patients. We also found that the NLR could enhance the predictive power of the CLIP score for DFS in these patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the important role of the NLR in prediction of prognosis for HCC with PVTT/HVTT after hepatectomy.

We found that the OS of the patients whose preoperative NLR > 2.9 was shorter than that of those with NLR ≤ 2.9. An NLR > 2.9 was also identified as an independent predictor on multivariate analysis. These results are consistent with those of previously published articles in HCC patients who had undergone other treatments with various cut-offs[20-23,25,27-29,35,36]. Moreover, preoperative AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL and bilobular disease were identified as independent predictors of OS after operation in patients with HCC and PVTT/HVTT on multivariate analysis. The former is consistent with the results of previously published studies in a similar subpopulation of HCC patients who had undergone resection[9,37], while the latter was also recognized to be an independent prognostic factor for unresectable patients[38,39].

In the present study, poor prognostic indicators influencing DFS included an NLR > 2.9, AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL, Hgb > 130 g/L, ICGR15 ≤ 10%, and intraoperative blood loss > 1000 mL. These patients had poorer DFS on univariate analysis, although none of these factors were identified as independent predictors on multivariate analysis. In fact, no factors were identified as independent predictors on multivariate analysis. Moreover, the rate and pattern of recurrence in the NLR > 2.9 group showed no significant differences compared with those in the NLR ≤ 2.9 group. These results may suggest that tumor recurrence in the remnant liver after surgery was common and nearly inevitable in HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT, which was a major cause of unsatisfactory prognosis[9,40,41]. Therefore, adjuvant treatment such as TACE and TAI could significantly improve the prognosis of HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT[40,41]. However, this result did not mean that the NLR was not associated with recurrence. Our results showed a significant association between the elevated NLR and tumor size. Previous studies have shown that tumor size > 3 cm on imaging is an independent predictor of microvascular invasion[42]. Additionally, several studies have indicated that preoperative elevated NLR can reflect tumor burden, malignancy, invasion, and metastasis[19,22-24,27,28,36].

The CLIP score consists of 4 variables, the Child-Pugh score, tumor morphology, serum AFP level, and portal vein invasion, which account for both liver function and tumor characteristics relevant to the prognostic assessment for patients with HCC[32]. It was confirmed that the CLIP score could reveal a class of HCC patients with an impressively more favorable prognosis and another class with a relatively shorter life expectancy in various population cohorts[32,43]. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first study confirming the prognostic predictive power of the CLIP score for HCC with PVTT/HVTT that could be enhanced by combining the NLR.

Inflammatory markers have long been linked with malignancy. Virchow first observed leukocytes appearing in neoplastic tissue in the mid 1800s[11]. Recently, consistent lines of evidence have suggested that there is a close relationship between the development of cancer and inflammation. As an inflammatory marker, NLR reflects an immune microenvironment that both favors tumor vascular invasion and suppresses the host immune surveillance[19].

A high NLR means relatively fewer lymphocytes and more neutrophil leucocytes, reflecting the impairment of the host immune response to tumors and a large reservoir of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)[13-15,22,24,34]. Circulating VEGF, whose primary sources are recognized as neutrophil leukocytes, has been established as a major contributor to tumor-related angiogenesis[44]. Elevated VEGF expression correlates with increased vascular density, higher rates of vascular invasion, and an increased tendency for seeding. Therefore, increased neutrophil leukocytes are related to an increased risk of recurrence in HCC patients[22,44]. Many studies have demonstrated that once the T-lymphocyte-mediated antitumor response is impaired and the cytotoxic CD81 lymphocyte subpopulation is dysfunctional, the lymphocytes may diminish, possibly leading to impaired defense against the tumor[22,45]. Okano et al[45] found that the extent of lymphocytic infiltration between the metastatic nodule and normal hepatic tissue may reflect host defensive activity in the liver and is associated with the outcome in patients who underwent hepatectomy for liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Patients with dense tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) had better outcomes than those with weak TILs after operation. Our results showed that an elevated NLR had significant associations with tumor size and liver function. Taken together, it was confirmed that an elevated NLR can indirectly reflect the tumor burden, vascular invasion, a high risk of tumor recurrence, and shorter survival after resection.

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) have been shown to have tumor-promoting effects, with a high density of TAMs in tumors reported to be associated with a poor prognosis. Some reports have indicated that macrophage infiltration into HCC is related to the aggressiveness of the tumor[46]. Maniecki et al[47] showed that a high infiltration of TAMs in HCC was related to a high NLR[28]. TAMs express certain cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-8, within the tumor, and these cytokines may promote systemic neutrophilia. Ubukata et al[48] demonstrated that a high NLR is significantly correlated with a high level of Th2 cells, which can polarize macrophages to TAMs through expressing certain cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-10. A high NLR is associated with high infiltration of TAMs and high inflammatory cytokine production in the tumor. Some studies have reported that TAMs are closely related to proinflammatory cytokine IL-17[49]. Peritumoral IL-17 may enhance systematic neutrophil leukocytes and play an important role in tumor progression[28,50]. Therefore, a similar mechanism may be one of the reasons for the NLR elevation in HCC patients. Some researchers have suggested that a high infiltration of TAMs is a first and important step of NLR elevation[28]. However, further examination is necessary to elucidate the mechanism.

The power of the present research was limited by its retrospective nature, single-center data, and relatively small sample size. More molecular experiments are needed to clarify the detailed molecular mechanism of the role that NLR plays in HCC with PVTT/HVTT. In consideration of these limitations, we believe that cross-validation in independent and larger patient cohorts, possibly in a prospective setting, should be mandatory before the NLR can be confidently incorporated as a validated biomarker to guide treatment decisions.

Although only 81 cases were included in our study, achieving this number of cases was difficult given the rarity of HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT who are suitable for hepatic surgery. We are the first to demonstrate that the NLR could predict the prognosis of HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT after hepatectomy. As described previously, the NLR may reflect the complex interplay between inflammatory mediators and angiogenic factors that are known to influence the survival of HCC patients. Moreover, unlike other complex molecular markers, the NLR is easy to compute and is universally available because it is derived from laboratory measures that are routinely assessed before operation. NLR could be used as a potential prognostic predictor for HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT after hepatectomy.

COMMENTS

Background

Portal/hepatic vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT/HVTT) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a sign of advanced-stage disease and is associated with a poor prognosis. This study investigated whether the preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) could predict the prognosis of these patients after hepatectomy.

Research frontiers

PVTT/HVTT in HCC is a sign of advanced-stage disease and is associated with a poor prognosis. Substantial evidence has recently shown that hepatectomy can improve the survival of HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT, although the median survival duration is still unsatisfactory. The reasons for this remain unclear and seem to be complex and multifactorial.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The presence of a systemic inflammatory response can be detected by the elevation of the NLR, which has been shown to be associated with a poorer prognosis in patients with various types of malignant tumors. This study confirmed that the NLR could be used as a potential prognostic predictor for HCC patients with PVTT/HVTT after hepatectomy.

Applications

The results of the present study may identify a new serum marker for predicting the post-operative survival of these patients.

Peer-review

Although the power of the present research was limited by its retrospective nature, single center data, and relatively small sample size, the paper is well written and surely gives new ideas in the preoperative evaluation of such complex patients.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center. The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Informed consent statement: Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by verbal consent. Individuals cannot be identified based on the data presented.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exist.

Data sharing statement: The data are available from the Sun Yat-Sun University Cancer Center Institutional Data Access/Ethics Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to the confidential data. Address: Sun Yat-Sun University Cancer Center Institutional Data Access, 651 Dongfeng East Road, Guangzhou 510060, China. sfz@sysucc.org.cn.

Peer-review started: October 14, 2016

First decision: December 28, 2016

Article in press: February 17, 2017

P- Reviewer: Marzano C S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Ma JY E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Okuda K. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent progress. Hepatology. 1992;15:948–963. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amitrano L, Guardascione MA, Brancaccio V, Margaglione M, Manguso F, Iannaccone L, Grandone E, Balzano A. Risk factors and clinical presentation of portal vein thrombosis in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2004;40:736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calvet X, Bruix J, Brú C, Ginés P, Vilana R, Solé M, Ayuso MC, Bruguera M, Rodes J. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma in Spain. Five year’s experience in 249 cases. J Hepatol. 1990;10:311–317. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90138-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JM, Kwon CH, Joh JW, Park JB, Ko JS, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Park CK. The effect of alkaline phosphatase and intrahepatic metastases in large hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:40. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llovet JM, Bustamante J, Castells A, Vilana R, Ayuso Mdel C, Sala M, Brú C, Rodés J, Bruix J. Natural history of untreated nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for the design and evaluation of therapeutic trials. Hepatology. 1999;29:62–67. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pawarode A, Voravud N, Sriuranpong V, Kullavanijaya P, Patt YZ. Natural history of untreated primary hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 157 patients. Am J Clin Oncol. 1998;21:386–391. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199808000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohkubo T, Yamamoto J, Sugawara Y, Shimada K, Yamasaki S, Makuuchi M, Kosuge T. Surgical results for hepatocellular carcinoma with macroscopic portal vein tumor thrombosis. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:657–660. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen XP, Qiu FZ, Wu ZD, Zhang ZW, Huang ZY, Chen YF, Zhang BX, He SQ, Zhang WG. Effects of location and extension of portal vein tumor thrombus on long-term outcomes of surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:940–946. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JS, Wang Q, Chen XL, Huang XH, Liang LJ, Lei J, Huang JQ, Li DM, Cheng ZX. Clinicopathologic characteristics and surgical outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis. J Surg Res. 2012;175:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaiswal M, LaRusso NF, Burgart LJ, Gores GJ. Inflammatory cytokines induce DNA damage and inhibit DNA repair in cholangiocarcinoma cells by a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2000;60:184–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh SR, Cook EJ, Goulder F, Justin TA, Keeling NJ. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:181–184. doi: 10.1002/jso.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez D, Morris-Stiff G, Toogood GJ, Lodge JP, Prasad KR. Impact of systemic inflammation on outcome following resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:513–518. doi: 10.1002/jso.21001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatti I, Peacock O, Lloyd G, Larvin M, Hall RI. Preoperative hematologic markers as independent predictors of prognosis in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: neutrophil-lymphocyte versus platelet-lymphocyte ratio. Am J Surg. 2010;200:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamanaka T, Matsumoto S, Teramukai S, Ishiwata R, Nagai Y, Fukushima M. The baseline ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes is associated with patient prognosis in advanced gastric cancer. Oncology. 2007;73:215–220. doi: 10.1159/000127412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao Y, Yuan D, Liu H, Gu X, Song Y. Pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is associated with response to therapy and prognosis of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:471–479. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1347-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pichler M, Hutterer GC, Stoeckigt C, Chromecki TF, Stojakovic T, Golbeck S, Eberhard K, Gerger A, Mannweiler S, Pummer K, et al. Validation of the pre-treatment neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in a large European cohort of renal cell carcinoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:901–907. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang GY, Yang Y, Li H, Zhang J, Jiang N, Li MR, Zhu HB, Zhang Q, Chen GH. A scoring model based on neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts recurrence of HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 20.Pinato DJ, Sharma R. An inflammation-based prognostic index predicts survival advantage after transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Res. 2012;160:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Gong F, Li L, Zhao M, Song J. Diabetes mellitus and the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predict overall survival in non-viral hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1704–1710. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halazun KJ, Hardy MA, Rana AA, Woodland DC, Luyten EJ, Mahadev S, Witkowski P, Siegel AB, Brown RS, Emond JC. Negative impact of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio on outcome after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;250:141–151. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a77e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Limaye AR, Clark V, Soldevila-Pico C, Morelli G, Suman A, Firpi R, Nelson DR, Cabrera R. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts overall and recurrence-free survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:757–764. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motomura T, Shirabe K, Mano Y, Muto J, Toshima T, Umemoto Y, Fukuhara T, Uchiyama H, Ikegami T, Yoshizumi T, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio reflects hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation via inflammatory microenvironment. J Hepatol. 2013;58:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Chen ZH, Ma XK, Chen J, Wu DH, Lin Q, Dong M, Wei L, Wang TT, Ruan DY, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio acts as a prognostic factor for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:11057–11063. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dan J, Zhang Y, Peng Z, Huang J, Gao H, Xu L, Chen M. Postoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio change predicts survival of patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing radiofrequency ablation. PloS one. 2013;8:e58184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao W, Zhang J, Zhu Q, Qin L, Yao W, Lei B, Shi W, Yuan S, Tahir SA, Jin J, et al. Preoperative Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a New Prognostic Marker in Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Curative Resection. Transl Oncol. 2014;7:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mano Y, Shirabe K, Yamashita Y, Harimoto N, Tsujita E, Takeishi K, Aishima S, Ikegami T, Yoshizumi T, Yamanaka T, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a predictor of survival after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective analysis. Ann Surg. 2013;258:301–305. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318297ad6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harimoto N, Shirabe K, Nakagawara H, Toshima T, Yamashita Y, Ikegami T, Yoshizumi T, Soejima Y, Ikeda T, Maehara Y. Prognostic factors affecting survival at recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after living-donor liver transplantation: with special reference to neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio. Transplantation. 2013;96:1008–1012. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182a53f2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646–649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamada R, Sato M, Kawabata M, Nakatsuka H, Nakamura K, Takashima S. Hepatic artery embolization in 120 patients with unresectable hepatoma. Radiology. 1983;148:397–401. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.2.6306721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Investigators. A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients: the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) investigators. Hepatology. 1998;28:751–755. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halazun KJ, Aldoori A, Malik HZ, Al-Mukhtar A, Prasad KR, Toogood GJ, Lodge JP. Elevated preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival following hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez D, Farid S, Malik HZ, Young AL, Toogood GJ, Lodge JP, Prasad KR. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic predictor after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2008;32:1757–1762. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng YB, Zhao W, Liu B, Lu LG, He X, Huang JW, Li Y, Hu BS. The blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma receiving sorafenib. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:5527–5531. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.9.5527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertuzzo VR, Cescon M, Ravaioli M, Grazi GL, Ercolani G, Del Gaudio M, Cucchetti A, D’Errico-Grigioni A, Golfieri R, Pinna AD. Analysis of factors affecting recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation with a special focus on inflammation markers. Transplantation. 2011;91:1279–1285. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182187cf0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi J, Lai EC, Li N, Guo WX, Xue J, Lau WY, Wu MC, Cheng SQ. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2073–2080. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0940-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mondazzi L, Bottelli R, Brambilla G, Rampoldi A, Rezakovic I, Zavaglia C, Alberti A, Idèo G. Transarterial oily chemoembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. Hepatology. 1994;19:1115–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamashita Y, Takahashi M, Koga Y, Saito R, Nanakawa S, Hatanaka Y, Sato N, Nakashima K, Urata J, Yoshizumi K. Prognostic factors in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with transcatheter arterial embolization and arterial infusion. Cancer. 1991;67:385–391. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910115)67:2<385::aid-cncr2820670212>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng BG, He Q, Li JP, Zhou F. Adjuvant transcatheter arterial chemoembolization improves efficacy of hepatectomy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein tumor thrombus. Am J Surg. 2009;198:313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaohua L, Qiaoxuan W, Peng S, Qing L, Zhongyuan Y, Ming S, Wei W, Rongping G. Surgical Strategy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients with Portal/Hepatic Vein Tumor Thrombosis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vibert E, Azoulay D, Hoti E, Iacopinelli S, Samuel D, Salloum C, Lemoine A, Bismuth H, Castaing D, Adam R. Progression of alphafetoprotein before liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: a critical factor. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:129–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ueno S, Tanabe G, Sako K, Hiwaki T, Hokotate H, Fukukura Y, Baba Y, Imamura Y, Aikou T. Discrimination value of the new western prognostic system (CLIP score) for hepatocellular carcinoma in 662 Japanese patients. Cancer of the Liver Italian Program. Hepatology. 2001;34:529–534. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kusumanto YH, Dam WA, Hospers GA, Meijer C, Mulder NH. Platelets and granulocytes, in particular the neutrophils, form important compartments for circulating vascular endothelial growth factor. Angiogenesis. 2003;6:283–287. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000029415.62384.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okano K, Maeba T, Moroguchi A, Ishimura K, Karasawa Y, Izuishi K, Goda F, Usuki H, Wakabayashi H, Maeta H. Lymphocytic infiltration surrounding liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2003;82:28–33. doi: 10.1002/jso.10188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou J, Ding T, Pan W, Zhu LY, Li L, Zheng L. Increased intratumoral regulatory T cells are related to intratumoral macrophages and poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1640–1648. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maniecki MB, Etzerodt A, Ulhøi BP, Steiniche T, Borre M, Dyrskjøt L, Orntoft TF, Moestrup SK, Møller HJ. Tumor-promoting macrophages induce the expression of the macrophage-specific receptor CD163 in malignant cells. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2320–2331. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ubukata H, Motohashi G, Tabuchi T, Nagata H, Konishi S, Tabuchi T. Evaluations of interferon-γ/interleukin-4 ratio and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio as prognostic indicators in gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:742–747. doi: 10.1002/jso.21725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuang DM, Peng C, Zhao Q, Wu Y, Chen MS, Zheng L. Activated monocytes in peritumoral stroma of hepatocellular carcinoma promote expansion of memory T helper 17 cells. Hepatology. 2010;51:154–164. doi: 10.1002/hep.23291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuang DM, Zhao Q, Wu Y, Peng C, Wang J, Xu Z, Yin XY, Zheng L. Peritumoral neutrophils link inflammatory response to disease progression by fostering angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2011;54:948–955. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]