Abstract

Introduction

Tracheal intubation leading to injury of the airway is a rare complication of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). Tracheal trauma is not a described complication of TEE, and safety literature for this procedure remains silent on the matter. We describe the case of a patient on systemic anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy who underwent TEE and suffered massive hemoptysis requiring bronchial artery embolization (BAE).

Case presentation

An elderly patient was admitted to the hospital with recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation and shortness of breath. The patient underwent a TEE with successful synchronized cardioversion on hospital day #2. Later that day the patient experienced respiratory distress and hemoptysis and was intubated. Oropharyngeal and gastrointestinal sources of bleeding were excluded. A bronchoscopy revealed active bleeding from an ulceration in the bronchus intermedius (BI) of the right lung. A 7 French Arndt endobronchial blocker (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana) was placed and anticoagulation reversed. Bleeding stopped for two days, but then returned on hospital day #5, requiring BAE to the right bronchial artery. The procedure was successful, the patient was successfully extubated, and was discharged over the next 10 days.

Discussion

Massive hemoptysis and respiratory compromise as a result of tracheal trauma is not described in the TEE literature. This patient proved to be a difficult esophageal intubation secondary to a newly discovered Zenker's diverticulum. The risk for bleeding in this patient was higher secondary to anticoagulation with warfarin and antiplatelet therapy with ticagrelor. As in all cases of massive hemoptysis, key aspects of care in this case involved localization of bleeding, reversal of anticoagulation, and definitive management such as BAE.

Conclusions

Tracheal trauma is not a described complication of TEE, but clinicians should be mindful of this possible complication in patients receiving anticoagulation. Typical management for massive hemoptysis was successful in this patient.

1. Presentation

A 71-year-old man with a past medical history significant for coronary artery disease (CAD) presented to our institution's outpatient cardiology clinic with four weeks of dyspnea on exertion. He was found to be hypoxic with oxygen saturations of 80% on ambient air, and was directly admitted to the hospital ward for further evaluation. His past medical history included percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) five months prior to presentation, for which he had four drug-eluting stents placed. His history was also notable for recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation and a 72-pack-year smoking history. His medications included daily warfarin after the recent diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, and ticagrelor following his PCI.

His vital signs were normal except for the noted hypoxia. The patient's physical exam was notable for an irregularly irregular heart rhythm, III/VI systolic murmur radiating to the axilla and bibasilar crackles on lung auscultation. Routine labs revealed a normal complete blood count save for a microcytic anemia with hemoglobin of 10.6g/dL, and normal basic metabolic panel. INR was elevated at 1.8. A computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) was performed, which was negative for pulmonary emboli, but revealed mosaic attenuation in the lung bases, bronchial wall thickening, and septal thickening.

The patient's hypoxia was felt to be from atrial fibrillation leading to mild fluid overload, and the decision was made to pursue synchronized cardioversion. The following afternoon he underwent a trans-esophageal echocardiogram (TEE) under conscious sedation, atrial thrombi were excluded, and he was electrically cardioverted from atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. Two attempts were required to pass the TEE probe into the esophagus, with the first attempt believed to be a tracheal pass.

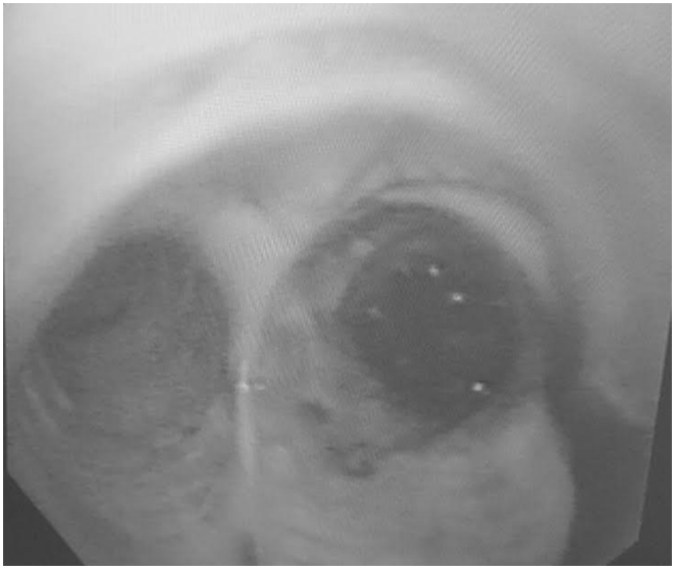

90 minutes following the procedure, he was found to be persistently hypoxic, requiring supplemental oxygen administration with a non-rebreather mask to maintain oxygen saturations above 90%. He developed a persistent cough and had several episodes of small-volume hemoptysis, no more than a teaspoon at a time. He was transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit for further monitoring. He developed minor epistaxis and underwent flexible nasolaryngoscopy, which excluded an upper airway source of bleeding. After multiple episodes of melena, he was electively intubated to undergo an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, which revealed a normal upper GI tract. A CT scan of the chest was consistent with acute pulmonary hemorrhage (Fig. 1). Ticagrelor and warfarin were resultantly held and his coagulopathy was reversed. He began to have large volume hemoptysis, for which he underwent a flexible bronchoscopy that revealed massive hemorrhage from an ulcer along the medial aspect of the bronchus intermedius (Fig. 2). Hemorrhage obscured the right lower lobe. Hemorrhage was not stopped with iced saline, and began to compromise the left lung leading to hypoxia.

Fig. 1.

CT scan of chest following massive hemoptysis, demonstrating occlusion of the bronchus intermedius and ground glass and consolidative opacities in the right middle lobe.

Fig. 2.

Images obtained from emergent bronchoscopy demonstrating right mainstem bronchus hemorrhage.

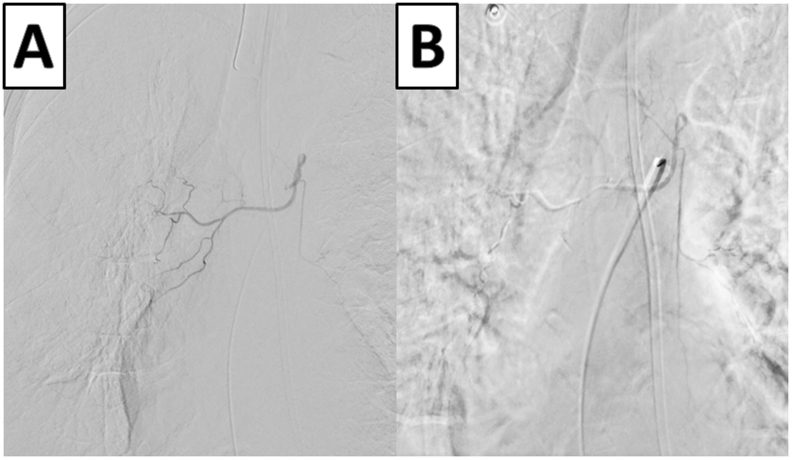

The patient was placed right side down. A pediatric bronchoscope was used to place a 7 French Arndt endobronchial blocker (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana) in the lumen of the bronchus intermedius, which staved off airway compromise. The following day a repeat bronchoscopy was performed and the endobronchial blocker removed after verification that the noted hemorrhaging had ceased. Two days later the patient developed worsening hypoxia and hemoptysis. Repeat bronchoscopy revealed active hemorrhage from the area previously noted in the right bronchus intermedius. The patient then underwent right bronchial artery embolization with n-butyl cyanocrylate glue and hemostasis was achieved (Fig. 3). The patient's hemoglobin stabilized, he was extubated four days later, and he was successfully discharged to a skilled nursing facility the following week.

Fig. 3.

Representative images from the described bronchial artery embolization. Figure 3A: Visualization of the right bronchial artery prior to intervention. Figure 3B: Right bronchial artery following embolization.

2. Discussion

We describe a case of a patient on anticoagulation who underwent TEE cardioversion with inadvertent tracheal intubation, resulting in massive hemoptysis. Though not previously described, we believe traumatic damage to the bronchus occurred because of the temporal relationship between hemoptysis and respiratory compromise, as well as the anatomic feasibility of the bronchial ulcer location. The patient also had chest CT scans both before and after clinical decompensation, which evolved from a pattern of volume overload to one of right-sided consolidative opacities and airway plugging. The patient was not intubated prior to the TEE and onset of hemoptysis, excluding the possibility of traumatic endotracheal tube placement.

Inadvertent tracheal intubation with a TEE probe is a complication described sporadically in the literature. Prior reports have detailed transient hypoxia and endotracheal tube displacement, though hemorrhage has not been described [1], [2]. Risk factors for tracheal intubation appear to be altered mentation, depressed upper airway reflexes, and dysfunction of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract [1]. Esophageal perforation and ischemic damage have been observed, usually in patients with pre-existing upper GI disorders and in cases where excessive and prolonged force was applied [3]. Damage is felt to be secondary to the probe tip's stiffness, large size, and range of motions required to obtain adequate image quality [3]. It is also worth noting that guidance of the TEE probe into the esophagus is done without direct visualization of the oropharyngeal cavity. Proper TEE placement is based on skill of the operator and familiarity of sonographic anatomical landmarks.

Our patient had numerous risk factors predisposing him to tracheal damage: 1) he received conscious sedation for the TEE, 2) he received topical anesthetics which impaired his normal cough reflex, and 3) he was found on endoscopy to have an upper esophageal diverticulum (i.e. Zenker's diverticulum) which may have prohibited the easy passage of the TEE probe into the esophagus. Though published guidelines place the risk of major hemorrhage to be <0.01% [4], our patient was at an elevated hemorrhage risk given the concomitant use of warfarin and ticagrelor.

Care for this patient and others with massive hemoptysis involves numerous critical steps. As provided to this patient, clinicians should intubate for airway protection, administer volume resuscitation, and reverse any coagulopathy [5], [6]. Localization of the source of hemorrhage is important in management; as was illustrated in our case, selective ventilation of the uncompromised lung allowed for respiratory stabilization. Identification of the right lung as the site of bleeding also allowed for definitive treatment via selective right bronchial artery embolization.

3. Conclusions

Inadvertent tracheal TEE insertion can cause bronchial injury and hemorrhage. Risk factors include GI dysfunction, altered mental status, and coagulopathy. Management should include typical steps to control massive hemoptysis.

Abbreviations

- BAE

bronchial artery embolization

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CTPA

computed tomography pulmonary angiogram

- GI

gastrointestinal

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- TEE

trans-esophageal echocardiogram

References

- 1.Sutton D.C. Accidental transtracheal imaging with a transesophageal echocardiography probe. Anesth. Analg. 1997;85(4):760–762. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199710000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortega R., Hesselvik J.F., Chandhok D., Gu F. When the transesophageal echo probe goes into the trachea. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 1999;13(1):114–115. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(99)90201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramadan A.S., Stefanidis C., Ngatchou W., LeMoine O., De Canniere D., Jansens J.L. Esophageal stents for iatrogenic esophageal perforations during cardiac surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007;84(3):1034–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn R.T., Abraham T., Adams M.S., Bruce C.J., Glas K.E., Lang R.M., Reeves S.T., Shanewise J.S., Siu S.C., Stewart W., Picard M.H., American Society of Echocardiography, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transesophageal echocardiographic examination: recommendations from the american society of echocardiography and the society of cardiovascular anesthesiologists. Anesth. Analg. 2014;118(1):21–68. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lordan J.L., Gascoigne A., Corris P.A. The pulmonary physician in critical care * Illustrative case 7: assessment and management of massive haemoptysis. Thorax. 2003;58(9):814–819. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.9.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jean-Baptiste E. Clinical assessment and management of massive hemoptysis. Crit. Care Med. 2000;28(5):1642–1647. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200005000-00066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]