Highlights

-

•

Gastrointestinal tuberculosis and colonic cancer carry a similar clinicoradiological profile.

-

•

Colonoscopic biopsy is the main investigation to be considered for the diagnosis.

-

•

Gene xpert has evolved as the diagnostic tool for tuberculosis with high specificity.

Abbreviations: ESR, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; ADA, Adenosine Deaminase; CT, Computerized Tomography; CEA, Carcino Embryonic Antigen; CA 19-9, Cancer Antigen 19-9; AKT, Anti Koch’s Treatment; MTB, Mycobacterium Tuberculosis; IBD, Inflammatory Bowel Disease; GITB, Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis

Keywords: Case report, Gastrointestinal tuberculosis, Colonic cancer, Crypt abscess, Crohn’s disease, Inflammatory bowel disease

Abstract

Introduction

Gastrointestinal tuberculosis is common in the developing world especially in the lower socioeconomic groups. In elderly, it may mimic malignancy.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old female presented with a 6 month history of diffuse pain in abdomen with low grade fever and loss of weight and appetite. Clinically, differential of malignancy of the large bowel was considered. The computerized tomography(CT) scan of the abdomen revealed a diffuse concentric long segmental thickening of terminal ileum, ileo ceacal junction, ascending colon and narrowing of the transverse colonic end of the splenic flexure suggesting an infective etiology. Colonoscopy showed an ulcero-nodular lesion at the splenic flexure raising the possibility of colonic cancer and thickening of ascending colon and caecum. Colonoscopic biopsy from both sites, on histopathology, showed a moderate mixed inflammation and occasional lymphoid collection and crypt abscesses in the lamina propria giving a differential of tuberculosis or Crohn‘s disease. Biopsy smear showed occasional acid fast bacilli(AFBs) and the gene Xpert detected mycobacterium tuberculosis(MTB). The patient was started on anti Koch’s therapy(AKT).

Discussion

In this case the differential diagnosis was malignancy of the colon, inflammatory bowel disease and tuberculosis as all these conditions may have similar clinical profile and radiological findings. Tuberculosis of bowel was considered as the most probable diagnosis due to the CT findings. But the colonoscopy suggested malignant etiology.

Conclusion

Possibility of tuberculosis should be kept in mind while dealing with synchronous lesions in large intestine.

1. Introduction

There were an estimated 2.5 million cases of tuberculosis in India in 2015 [WHO, Geneva, 2015]. Gastrointestinal tuberculosis is common in the developing world especially in the lower socioeconomic groups. The abdominal TB, which is not so commonly seen as pulmonary TB, can be a source of significant morbidity and mortality and is usually diagnosed late due to its nonspecific clinical presentation [1].

Approximately 15%-25% of cases with abdominal TB have concomitant pulmonary TB [2], [3]. The diagnosis of gastrointestinal tuberculosis is difficult in the middle aged as the clinic-radio-pathological spectrum mimics malignancy and Inflammatory bowel Disease (IBD). This case was managed at a tertiary care teaching hospital, academic setting.

2. Case presentation

A 46 year old female patient came walking to the outpatient department with a 6 month history of diffuse abdominal pain with low grade fever and loss of appetite and weight. No significant past medical or surgical history. There was no history of pulmonary tuberculosis.

On examination, general condition was fair, vitals were stable. Abdominal examination revealed a soft non tender abdomen with a normal digital per rectal examination.

Haematological investigations were normal except erythrocyte sedimentation rate(ESR) which was 80 mm (0–30 mm normal). Her serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen(CEA), cancer antigen19-9(CA 19-9) and serum adenosine deaminase(ADA) levels were within normal limits.

Contrast enhanced CT(CECT) abdomen revealed a diffuse concentric long segmental circumferential wall thickening of terminal ileum, ileocaecal(IC) junction and ascending colon with peripheral fat stranding and lymphadenopathy with narrowing at the splenic flexure (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 1.

Showing thickening at the IC junction.

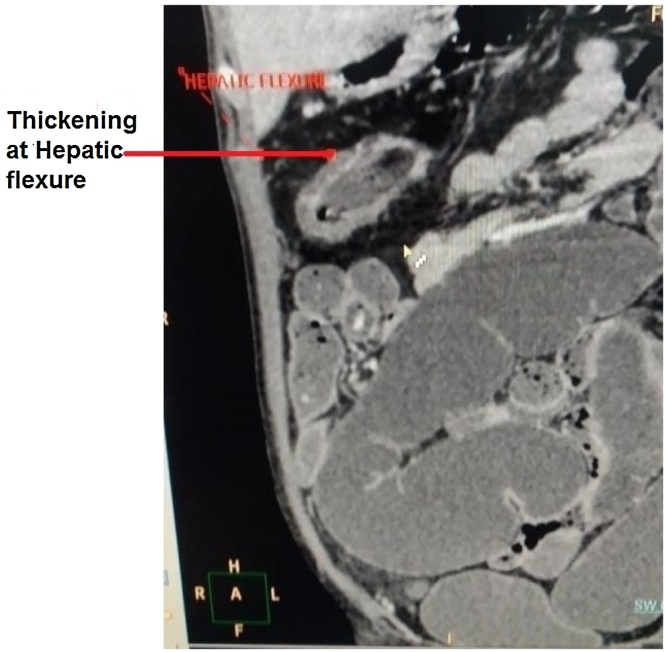

Fig. 2.

Showing thickening at hepatic flexure.

Fig. 3.

Showing narrowing at the splenic flexure.

Colonoscopy showed an ulceronodular lesion with lumen compromise at the splenic flexure and thickening of the ileocaecal junction. Biopsy was taken from both the sites and sent for histopathological examination and also for culture and gene xpert for MTB.

Pathology showed moderate mixed inflammation and occasional lymphoid collection in the lamina propria with no evidence of malignancy. There were also occasional crypt abscesses which raised suspicion of inflammatory bowel disease. The final diagnosis of tuberculosis of the intestine was made as the biopsy smear showed AFBs and the Gene Xpert detected MTB. The patient was/started on Anti tubercular therapy. At 6 month follow up, patient is asymptomatic. Repeat CT scan shows no narrowing (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Showing resolution of narrowing at splenic flexure.

3. Discussion

In India, TB is one of the commonest infections affecting poor socioeconomic groups.

Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis is a major health problem and is a rising threat due to transglobal migration [4]. It is not entirely known if the bacteria colonize the bowel by penetrating through the wall or enter that site through the arterial circulation. The most common site of gastrointestinal involvement is the ileocecal region which is involved in 64% of cases of gastrointestinal TB and is thought to be due to the abundant lymphoid tissue and the stasis of the stools around that segment. The rest of the colon is affected with decreasing frequency further away from ileo-caecal area with rectosigmoid being less frequent [5].

The symptoms are not specific and can mimic diseases like Crohn's disease and colon cancer. Commonest complaints are abdominal pain 80.6%, weight loss 74.63%, loss of appetite 62.69%, fever 40.3%, loose stools 16.42% and alternate constipation and diarrhoea 25.37% [1].

Our patient had no evidence of pulmonary TB as is seen with 75–80% of patients with gastrointestinal tuberculosis. It is not clear why some are affected by extra-pulmonary TB and some not, but it is shown that race, age, underlying disease, the genotype of the bacteria and the immune status are factors that are related to the pathogenesis [6]. The immune status is also found to affect manifestation of bowel TB. The ulcerative form (60%) tends to be more common in the immunocompromised individuals and the hypertrophic form (10%) in immunocompetent patients. This patient had a negative HIV test and CT image showed hypertrophic form.

In this case, acid fast bacilli were detected on Ziehl Nelsen staining. Gene Xpert was also positive. Gene Xpert has a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 98% [7], which is sufficient to make a diagnosis of tuberculosis. Crohn's disease can have similar features as it can also present with skip lesions in two different part of the bowel and have transmural granulomatous inflammation and crypt abcesses in histology.

The differential diagnosis to be considered from the history and investigations are malignancy of the colon, inflammatory bowel disease and TB as all these conditions have similar clinical profile and radiological findings. Colonic cancer was the most probable diagnosis considering the CT scan findings of the patient. But looking at the presenting complaints of the patient and TB being so prevalent in India, it had equal importance while considering it as a differential.

It is important to differentiate Crohn's disease from TB as misdiagnosing Crohn's disease instead of TB, can have deleterious effects for the patient due to the immunosuppressive medications given for Crohn's disease.

Successful treatment of colonic TB can be achieved with conservative management with oral anti-TB medications unless a surgical emergency like perforation or obstruction occurs. Therefore, in cases of high-risk patients for TB presenting with non-specific symptoms with colonic thickening on imaging, it is important to biopsy the lesion during colonoscopy as this may help conservative treatment. However, close monitoring of the patient's response to medical treatment is required as failure of symptoms to regress and the lesions to decrease in size might be a hint of a more sinister underlying pathology, like carcinoma. In a paper by Falagas et al,it was shown that there is evidence of coexistence of TB and malignancy [8]. There is the possibility of development of cancer on the background of previous TB infection and the concurrent existence of TB and malignancy in the same patient. This can be explained by the fact than on a cellular level chronic TB infection may cause an imbalance between tissue damaging agents that can result in deoxyribonucleic acid

(DNA) damage and tissue repair mechanisms to generate a microenvironment that predisposes to malignant transformation [9]. This is thought to be due to production of nitric oxide and oxygen-free radicals and the increased synthesis of B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), which leads to increased antiapoptotic activity. Therefore, patient response should be closely monitored.

We encountered many cases of colonic TB in literature but we have not come across a case similar to this in which there is a colonic TB extending upto splenic flexure.

4. Conclusions

Clinicians need to have suspicion of gastrointestinal tuberculosis (TB) in their differential when dealing with patients with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, especially in the setting of high prevalence of the disease.

5. Learning points

-

1.

Gastrointestinal TB is one of the known causes of hypertrophic lesions on the bowel wall mimicking malignancy.

-

2.

CT scan and endoscopic biopsy form the major diagnostic tools for gastrointestinal tuberculosis.

-

3.

Conservative management is successful in the majority of cases.

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Source of funding

This article received no funding.

Ethical approval

Manuscript involves a case report for which approval was taken from “Ethics Committee for Academic Research Purpose, B. Y. L. Nair Ch Hospital, Mumbai” for its publication.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from patient and his relative to participate in this case report.

Consent for publication

Patient and his relatives consent was taken for publication of this case report.

Authors’ contribution

Concept design and preparation of manuscript: Dr. Prashant Lakhe, Dr. Jayashri Pandya.

Literature search: Dr. Asma Khalife.

Preparation of draft manuscript: Dr. Asma Khalife, Dr.Jayashri Pandya.

Registration of research studies

Researchregistry.com

2361.

Guarantor

Dr Jayashri Pandya.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [10]. http://www.scareguideline.com

Contributor Information

Prashant Lakhe, Email: prashant3lakhe@gmail.com.

Asma Khalife, Email: asma.khalife@gmail.com.

Jayashri Pandya, Email: smruti63@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Mukewar S., Ravi R., Prasad A.S., Dua K. Colon tuberculosis: endoscopic features and prospective endoscopic follow-up after anti-tuberculosis treatment. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2012;3:e24. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2012.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horvath K.D., Whelan R.L. Intestinal tuberculosis: return of an old disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1998;93:692–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.207_a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhan O., Pringot J. Imaging of abdominal tuberculosis. Eur. Radiol. 2002;12:312–323. doi: 10.1007/s003300100994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel N., Amarapurkar D., Agal S., Baijal R., Kulshrestha P., Pramanik S. Gastrointestinal luminal tuberculosis: establishing the diagnosis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2004;19:1240–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma R. Abdominal tuberculosis. Imaging Sci. Today. 2009;14:6. (Cited2016 Mar 31) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caws M., Thwaites G., Dunstan S. The influence of host and bacterial genotype on the development of disseminated disease with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2008;2013:1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang K., Lu W., Wang J., Zhang K., Jia S., Li F., Deng S., Chen M. Rapid and effective diagnosis of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance with Xpert MTB/RIF assay: a meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2012;64(6):580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falagas M.E., Kouranos V.D., Korterides P. Tuberculosis and malignancy. Q. J. Med. 2010;2013:461–487. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saunders B.M., Britton W.J. Life and death in the granuloma: immunopathology of tuberculosis. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2007;85:103–111. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., The SCARE group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]