Abstract

Purpose:

To assess choroidal perfusion before and after orbital decompression surgery in patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy.

Methods:

In this interventional case series, surgical decompression for optic nerve compromise was performed on four eyes of three patients with Graves' disease. Complete ophthalmic examination including visual acuity, color vision, and intraocular pressure assessment were done pre- and postoperatively. High-speed indocyanine green angiography was performed prior to surgery and was repeated one year after surgery.

Results:

In all three patients, choroidal perfusion defects were noted pre-operatively in the eyes with the compressive optic neuropathy. At 1 year after orbital decompression surgery, the defects improved or completely resolved. Improved visual acuity and color perception, as well as decreased intraocular pressure, were also noted postoperatively.

Conclusion:

Patients with Graves' orbitopathy may have abnormal choroidal perfusion even in the absence of optic neuropathy. Orbital decompression may improve choroidal circulation in these patients.

Keywords: Choroid, Circulation, Graves, Indocyanine Green Angiography

INTRODUCTION

Graves' disease (GD) is an autoimmune disorder of thyroid gland with autoantibodies that may lead to hyperthyroidism.[1] Presence of thyroid gland autoantibodies and eye disease distinguishes the disorder from other causes of hyperthyroidism. GD can lead to Graves' ophthalmopathy (GO), with patients developing proptosis, impaired ocular motility, and increased intraocular pressure.[2] In 3–5% of patients, the disease leads to orbitopathy and compressive optic neuropathy with decreased visual acuity and color perception, visual field defects, and sometimes even loss of vision.[2]

To avoid sight-threatening complications, early orbital decompression surgery is used to decompress the orbital contents, vessels, and optic nerve and to improve orbital vascular circulation after failed medical management.[2] It is unknown whether orbital decompression surgery can also affect choroidal perfusion in cases of orbital compartment syndrome. The aims of this article are to assess choroidal perfusion in patients with GO and to investigate whether orbital decompression surgery improves choroidal and vascular perfusion of orbital vessels.

METHODS

This study was approved by the MedStar Washington Hospital Center institutional review board. Participants provided written informed consent and completed study procedures July 2010 – November 2013.

An oculoplastic surgeon (NN) performed orbital decompression surgery for compressive optic neuropathy on four (n = 4) eyes of three patients (average age 60 years). Compressive optic neuropathy was determined by presence of an afferent pupillary defect (APD), decreased visual acuity, decreased color vision assessed with Ishihara plates, visual field defects measured with visual field testing (Humphrey Field Analyzer, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA), increased intraocular pressure, and/or elevated optic disc. A full ophthalmologic exam was performed pre-operatively and 1, 3, and 12 months postoperatively.

RESULTS

We report 3 cases with Graves' ophthalmopathy before and after orbital decompression surgery.

Case 1

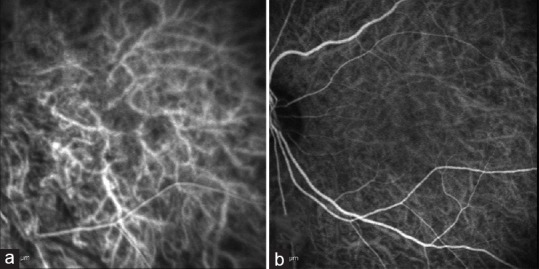

A 64-year-old African American woman with GD developed GO in both eyes, with compressive optic neuropathy in the left eye. On examination, she had a + APD in the left eye, decreased color vision (incorrect responses on 12/15 plates), proptosis, and severely limited motility in all fields of gaze in the left eye. Pre-operative indocyanine green angiography (ICG) was performed [Figure 1a]. Medium and large choroidal vessels were prominent, but small choroidal vessels were not seen well. The patient underwent three-wall orbital decompression surgery in her left eye.

Figure 1.

(a) Case #1 OS. Pre-operative ICG. Medium and large vessels are prominent with no detail of the smaller choroidal vessels. (b) Case #1 OS. 1-year post-operative ICG. Choroidal circulation re-established with smaller choroidal vessels slightly more prominent compared to previous study.

One year after orbital decompression surgery, the choroidal circulation was improved, with smaller choroidal vessels more prominent compared with the pre-operative findings [Figure 1b].

Case 2

A 59-year-old African-American woman with GD developed GO in both eyes despite prior radioactive iodine therapy. Upon clinical examination, her best corrected visual acuity was 20/40 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left eye, with color vision slightly reduced in both eyes (13/15 color plates). External examination showed 2+ lid lag and retraction and significant proptosis in both eyes. The patient underwent two-wall orbital decompression surgery in both eyes.

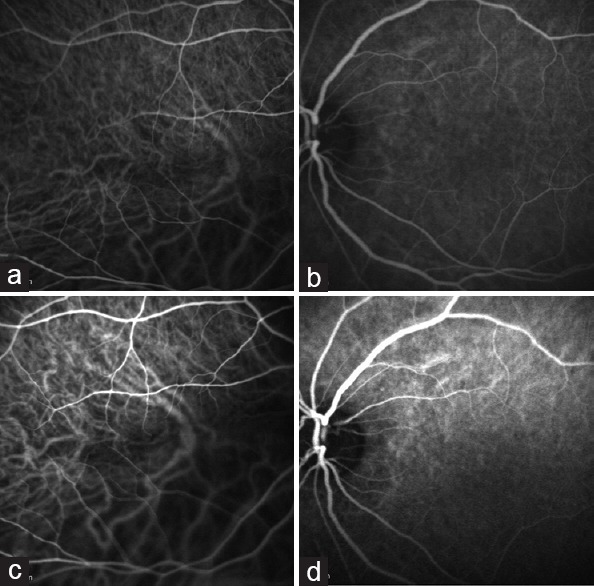

In the pre-operative high speed ICG angiogram [Figure 2a and b]. Both eyes showed delayed choroidal filling, which was worse in the right eye. The right eye also showed loss of small vessel detail in the inferior macula. One year post-surgery, choroidal circulation was improved in the right eye, with some residual filling defects inferiorly [Figure 2c], and in the left eye, the choroidal circulation was completely restored [Figure 2d].

Figure 2.

(a) Case #2 OD. Pre-operative ICG. Noted delay in choroidal filling. Superior macula is more normal appearing with loss of small vessel detail in the inferior macula. Only medium and large vessels are seen. (b) Case #2 OS. Pre-operative ICG. Slight delay in choroidal filling is noted. Left eye shows more prominent small vessel detail compared with the right eye. (c) Case #2 OD. 1-year post-operative ICG. Improved choroidal circulation. (d) Case #2 OS. 1-year post-operative ICG. Restored choroidal circulation.

Case 3

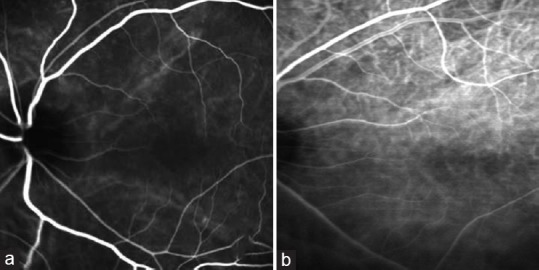

A 58-year-old Caucasian woman presented with GO, intraocular pressure of 28 mmHg, Humphrey visual field defects, and advanced cupping in the left eye. Her left eye exhibited 3 mm more proptosis than her right and a reduced color saturation. The patient underwent two-wall orbital decompression surgery in her left eye. High speed ICG performed 1 year post-operatively showed improvement in hypoperfusion of smaller vessels of posterior pole compared to pre-operative ICG [Figure 3a and b].

Figure 3.

(a) Case #3 OS. Pre-operative ICG. Slow filling of the choriocapillaris in the macula. Medium and large choroidal vessels are prominent without detail from smaller vessels. (b) Case #3 OS. 1-year post-operative ICG. Improvement in hypoperfusion.

DISCUSSION

Nearly 50% of individuals with GD have clinical involvement of the eyes, either thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy or GO.[3] Many of GO's clinical symptoms and signs can be explained by increased volume in orbital fatty connective tissue and extraocular muscles.[4] While in some patients, enlargement of the extraocular muscles is the predominant pathogenic change, in others the orbital tissue volume is significantly increased, with little if any eye muscle involvement.[4] Histologic studies have shown that extraocular muscle fibers, as well as orbital adipose tissue, are infiltrated by glycosaminoglycans, lymphocytes, and immune complexes, leading to edema, soft tissue expansion, increased intraorbital volume, and subsequently increased intraorbital pressure.[2] Early orbital decompression surgery is reserved for patients with vision-threatening compressive optic neuropathy or orbitopathy.[1] This develops secondary to discrepancy between the expanding extraocular volume and the non-expansile bony compartment of the orbit.[4] This discrepancy causes increased intraorbital pressure. Otto and colleagues[5] found that before surgical decompression, intraorbital pressure was markedly elevated in patients with GO, with surgery reducing the pressure by a mean of 10 mmHg. Riemann and associates[6] also reported increased intraorbital pressure in patients with GO.

Increased intraorbital pressure may compress orbital vasculature and affect hemodynamics. In an evaluation of retrobulbar blood supply in patients with inactive GD before and after decompression surgery, Perez-Lopez et al[7] found increased resistance indexes in the central retinal and ophthalmic arteries in patients with GO compared with control patients. Alp and colleagues[8] also found increased orbital venous congestion and decreased flow velocity in the superior ophthalmic vein in patients with GO compared to both patients with GD but without GO, and healthy control patients. Reversed flow in the superior ophthalmic vein was documented in 13% of GO patients.[8]

We found significant delay in choroidal filling as well as loss of details in choroidal vasculature in patients with compressive optic neuropathy. Orbital inflammation may be a possible pathogenic mechanism for development of these abnormal choroidal filling patterns. The inflammatory changes induced in the orbital fat and extraocular muscles seen in GD,[2] and the vascular endothelial cell damage observed in hyperthyroidism[9] could induce hemodynamic changes in the choroidal vessels, decreasing their perfusion. Furthermore, the cardiovascular effects of hyperthyroidism, such as increased cardiac output, could induce these hemodynamic changes.[10] Kurioka et al[11] measured retinal blood flow in patients with GD, concluding that patients with GD have altered retinal hemodynamics, possibly resulting from the cardiovascular effects of hyperthyroidism or from retro-orbital inflammation, especially when the extraocular muscles are more affected than the orbital fat.

We believe the abnormal choroidal perfusion in our patients was due to a combination of extraocular muscle enlargement and orbital fat expansion causing increased intraorbital pressure as well as inflammation. Our study also suggests that choroidal circulation abnormalities start with the smallest caliber vessels – the short posterior ciliary arteries supplying the macular area as well as the choriocapillaris. The outer layers of the retina, especially the rods and cones, are dependent mainly on the choroidal blood vessels.[12] Since the fovea contains only cones which are specialized for color vision,[12] loss of color vision could be caused by preferential poor choroidal blood flow from arteries that supply this area plus small vessel compromise to the optic nerve. Poor blood flow to the macular area also could explain central scotomas in these patients.[12] Poor choroidal perfusion to the long posterior ciliary arteries could compromise the retinal periphery, adding to peripheral visual field defects.[13]

The results of this study suggest that choroidal perfusion might be helpful in identifying early compressive orbitopathy in patients with GO. This study was limited by its small sample size. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography would also have been useful to evaluate choroidal thickness as an indirect measure for perfusion. Future directions include comparison of pre- and post-treatment choroidal perfusion in GD patients with orbitopathy resolved with conservative measures, versus those resolved with surgical decompression.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith TJ, Hegedus L. Graves' Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1552–1565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holds JB, Chang WJ, Durairaj VD, Foster JA, Gausas RE, Harrison AR, et al. Orbital Inflammatory and Infectious Disorders: Thyroid Eye Disease. In: Holds JB, Chang WJ, Durairaj VD, Foster JA, Gausas RE, Harrison AR, et al., editors. Orbit, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System: Basic and Clinical Science Course 2013-14. Singapore: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2013. pp. 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazarus JH. Epidemiology of Graves' orbitopathy (GO) and relationship with thyroid disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahn RS. Graves ophthalmopathy. N Eng J Med. 2010;362:726–738. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0905750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otto AJ, Koornneef L, Mouritis MP, Deen-van Leeuwen L. Retrobulbar pressures measured during surgical decompression of the orbit. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:1042–1045. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.12.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riemann CD, Foster JA, Kosmorsky GS. Direct orbital manometry in patients with thyroid-associated orbitopathy. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)00712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez-Lopez M, Sales-Sanz M, Rebolleda G, Casa-Llera P, Gonzalez-Gordaliza C, Jarrin E, et al. Retrobulbar ocular blood flow changes after orbital decompression in Graves' ophthalopathy measured by color Doppler imaging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:5612–5617. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alp MN, Ozgen A, Can I, Cakar P, Gunalp I. Colour Doppler imaging of the orbital vasculature in Graves's disease with computed tomographic correlation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1027–1030. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.9.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burggraaf J, Lalezari S, Emeis JJ, Vischer UM, de Meyer PH, Pijl H, et al. Endothelial function in patients with hyperthyroidism before and after treatment with proplanol and thiamazol. Thyroid. 2001;11:153–160. doi: 10.1089/105072501300042820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jabbar A, Pingitore A, Pearce SH, Zaman A, Iervasi G, Razvi S. Thyroid hormones and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:39–55. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurioka Y, Inaba M, Kawagishi T, Emoto M, Kumeda Y, Inoue Y, et al. Increased retinal blood flow in patients with Graves' disease: Influence of thyroid function and ophthalmopathy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001;144:99–107. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1440099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall JE. The Eye: II. Receptor and Neural Function of the Retina. In: Hall JE, editor. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. 13th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 647–55. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Standring S, Anand N, Birch R, Collins P, Crossman AR. Eye Uvea. In: Standring S, editor. Gray's Anatomy. 40th edition. Spain: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 686–708. [Google Scholar]