Abstract

An electrophilic, imide-based, visible-light-promoted photoredox/Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction for the synthesis of aliphatic ketones has been developed. This protocol proceeds through N–C(O) bond activation, made possible through the lower activation energy for metal insertion into this bond due to delocalization of the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen by electron-withdrawing groups. The operationally simple and mild cross-coupling reaction is performed at ambient temperature and exhibits tolerance for a variety of functional groups.

Acylation is one of the most powerful protocols for the chemoselective formation of ketones, which are among the most fundamental and widespread functional groups in nature.1 Among transition-metal-catalyzed acylation strategies, Suzuki coupling has become an increasingly essential protocol to forge acyl–carbon bonds.2 Although the scope of the electrophilic partner in the acylative Suzuki coupling has been extended to different types of carboxylic acid derivatives, the use of acyl donors such as anhydrides,3 active esters,4 thiol esters,5 and amides6 is particularly attractive compared with acyl halides because these functional groups are generally more stable, nontoxic, and more widely available.

In contrast to the relative ease of carrying out transition-metal-catalyzed acylation using more highly electrophilic carboxylic acid derivatives such as carboxylic acid halides, anhydrides, and thioesters, cross-coupling via N–C bond oxidative addition of amides to generate acylmetal intermediates is inherently more challenging because of the strong conjugation interaction between the nN and πC=O* orbitals in amides, which engenders a higher barrier for metal insertion into the C(O)–N bond.7 The disruption of this conjugation by steric effects that increase the nonplanarity about the C–N amide bond or the delocalization of the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen by electron-withdrawing groups results in a lower barrier for the formation of the acylmetal intermediate.6 Although significant advances have taken place in transition-metal-catalyzed cross-couplings of amides with arylboronic acids, alkylation reactions have been restricted to the use of Weinreb amides with highly reactive organometallic nucleophiles8 and minimally functionalized alkylzinc reagents9 in transition-metal-catalyzed transformations. Extension of an acylative cross-coupling between amides and more functional-group-tolerant alkylboron reagents was viewed as a useful, complementary means by which more structural and functional group diversity could be introduced into the synthesis of alkyl ketones.

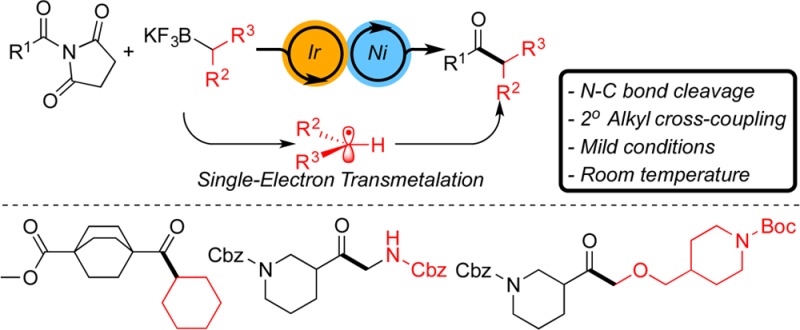

Recently, our laboratory developed a novel visible-light-promoted photoredox/Ni dual-catalytic cross-coupling method based on single electron transfer (SET) oxidation of alkyltrifluoroborates.10 In this method, under the collaborative roles of two distinct catalysts, an effective transmetalation occurs via the formation of radicals generated upon oxidation of the potassium alkyltrifluoroborates. In fact, this synergistic dual-catalytic approach is a versatile method that allows synthetically challenging Csp3–Csp2 bond formation processes to occur under mild conditions. We recently extended the scope of electrophiles to which this dual-catalytic cross-coupling could be applied from aryl halides to acyl chlorides.11 In a similar vein, the Doyle group previously utilized photoredox/Ni dual catalysis to acylate α to amines using anhydrides and thioesters,12 and in a collaborative effort the Rovis and Doyle groups developed an elegant enantioselective desymmetrization of meso-anhydrides using benzyltrifluoroborates as radical precursors by photoredox/Ni dual catalysis.13 In the course of our investigation to broaden the applications of this protocol, and also considering the abundance of amides and their stability in organic transformations,14 we investigated the efficiency of a similar protocol in acylation of potassium alkyltrifluoroborates via N–C bond activation of amides to generate aliphatic ketones (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Photoredox/Ni Dual-Catalytic Cross-Coupling of Amides with 2° Alkyl R–BF3K.

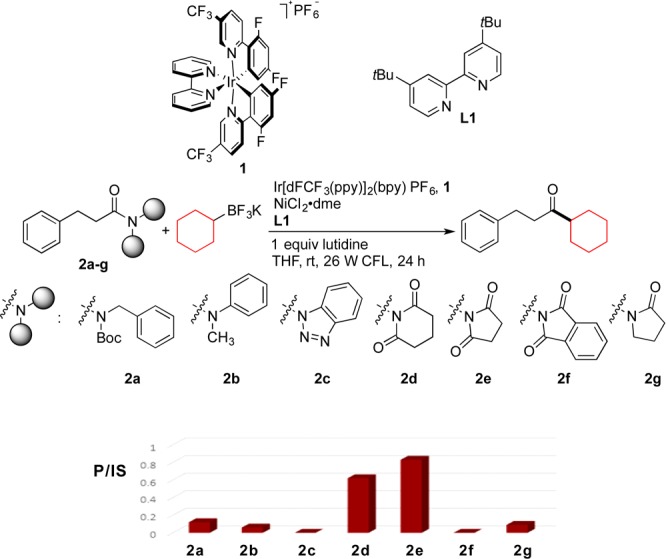

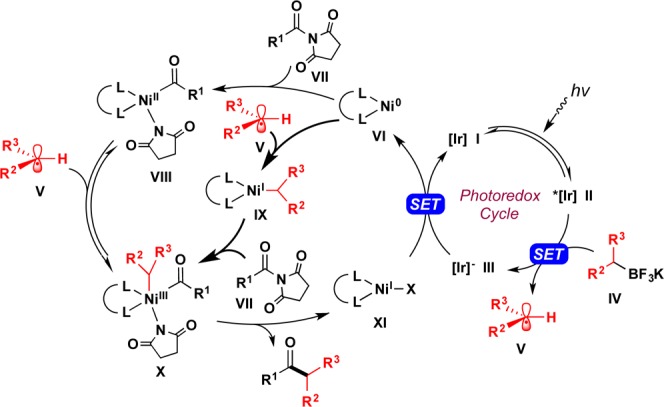

Our studies began by focusing on finding the best activated amide for this coupling reaction. Therefore, the cross-coupling of a variety of sterically and electronically activated amides derived from hydrocinnamic acid, as well as benzotriazole derivative 2c, was investigated by means of microscale high-throughput experimentation (HTE) using potassium cyclohexyltrifluoroborate as the coupling partner in the presence of Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(bpy)PF6 (1) [dF(CF3)ppy = 2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)pyridine, bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine] as a photocatalyst, nickel(II) chloride ethylene glycol dimethyl ether complex as a cross-coupling catalyst, and 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine (L1, dtbbpy) as a ligand at room temperature (Scheme 2).15 Both 1-(3-phenylpropanoyl)piperidine-2,6-dione (2d) and 1-(3-phenylpropanoyl)pyrrolidine-2,5-dione (2e) generated the desired cross-coupled product in good yields, but the highest product to internal standard ratio (P/IS) was obtained for the cross-coupling reaction of imide 2e. Incomplete consumption of starting material was the reason for the lower P/IS for the reaction using derivative 2d. Consequently, N-acylpyrrolidine-2,5-diones would be the best candidates as the electrophilic partner in an SET photoredox/Ni cross-coupling protocol. These imides are highly stable and easily accessed from the corresponding carboxylic acids.16 The proposed mechanism for this transformation, which is adapted from our studies on the cross-coupling of aryl halides with alkyltrifluoroborates, is shown in Scheme 3.17

Scheme 2. Graphical Chart of P/IS of the Cross-Coupling of a Variety of Activated Amides with Cyclohexyltrifluoroborate.

Scheme 3. Proposed Mechanism for the Photoredox Cross-Coupling of N-Acylpyrrolidine-2,5-diones with Alkyl–BF3K.

With the best amide derivative in hand, a more extensive screening of various reaction parameters (e.g., solvent, photocatalyst, Ni catalyst, ligand, and additive) was carried out using HTE to find the best overall conditions for the photoredox/Ni dual catalytic cross-coupling of N-acylpyrrolidine-2,5-diones with potassium alkyltrifluoroborates. In these screens, 2e and potassium cyclohexyltrifluoroborate were chosen as model coupling partners. As a result of the screens, although bpy and NiBr2·dme exceeded other ligands and nickel sources, respectively, in performance, preformed [Ni(dtbbpy)(H2O)4]Cl2 illustrated the best performance under the experimental conditions and afforded the highest yield (Figures S2 and S3).15 Interestingly, unlike our previous protocol using acyl chlorides as the electrophile,11 after screening of a variety of additives the best result was obtained without any additive (Figure S4). An investigation of the impact of the solvent on this cross-coupling revealed that 2-MeTHF was the best solvent (Figure S5). Further screens showed that using cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) as a cosolvent (2-MeTHF/CPME 5:1) increased the yield of the desired product. Finally, control experiments showed that all of the parameters were essential for the reaction to proceed (Table S1).15 Accordingly, treatment of 2e with potassium cyclohexyltrifluoroborate in the presence of 3 mol % photocatalyst 1 and 6 mol % [Ni(dtbbpy)(H2O)4]Cl2 in 2-MeTHF/CPME (5:1) as the solvent mixture at room temperature produced the desired ketone 3a in the highest yield (78%; Scheme 4).

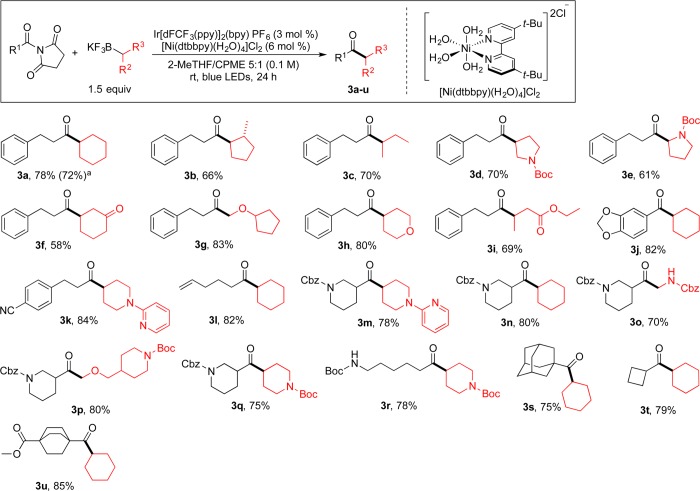

Scheme 4. Scope of the Cross-Coupling Reaction of N-Acyl Succinimides with Potassium Alkyltrifluoroborates.

Reaction performed on a 4.5 mmol scale with 1.5 mol % Ir photocatalyst 1 and 3 mol % [Ni(dtbbpy)(H2O)4]Cl2.

With suitable conditions in hand, a variety of imides were reacted with different potassium alkyltrifluoroborates to demonstrate the versatility of this novel Csp2–Csp3 protocol and to explore the substrate scope of the cross-coupling reaction with regard to both the imide and the alkyltrifluoroborate partner under the developed conditions (Scheme 4). All of the imides studied reacted well, generating the corresponding ketones in good yields. A single aromatic imide, generating ketone 3j, demonstrated the viability for this substructural class of electrophiles. Additionally, imides containing electrophilic functional groups, including esters (3u) and nitriles (3k), which would be prone to side reactions in the presence of more strongly nucleophilic organometallic reagents, participated in the cross-coupling reaction with great efficiency. The imide bearing a bulky group, 1-(adamantane-1-carbonyl)pyrrolidine-2,5-dione, generated the desired product in high yield (3s, 75%). Interestingly, imides possessing tert-butoxycarbonyl- and carboxybenzyl-protected primary (3r) and secondary amines (3m–q) were well-tolerated. Of note, our previous efforts to generate these nitrogen-containing aliphatic ketones via the cross-coupling of acyl chlorides with alkyltrifluoroborates were unsuccessful.11 Finally, 1-(5-hexenoyl)pyrrolidine-2,5-dione was also found to be a suitable reaction partner, with the terminal double bond remaining intact (3l, 82%).

A variety of potassium alkyltrifluoroborates functioned efficiently in this transition-metal-catalyzed acylation protocol as well. In the acylation of sec-butyltrifluoroborate, no regioisomerization was observed, and the desired product was obtained in 70% isolated yield (3c). The products derived from sterically hindered substrates such as 2-methylcyclopentyltrifluoroborate performed well with no isomerization and generated the trans diastereomer as the only product (3b, 66%). Notably, the developed protocol readily tolerated amines and nitrogen heterocycles (3k and 3m), which could be problematic in transformations of this type using more electrophilic acylating agents.18 Other aliphatic heterocyclic trifluoroborates containing oxygen (3h) or protected nitrogen atoms (3o–r) reacted efficiently under the reaction conditions. Moreover, this protocol is amenable to the coupling of α-aminoalkyltrifluoroborates (3e and 3o) to generate ketones bearing α-amino substitution that are broadly represented among pharmaceutically active compounds and complex natural products.19 α-Alkoxy ketones, which are versatile and valuable building blocks in the construction of various natural products,20 were also obtained in excellent yields by the cross-coupling reaction of α-alkoxymethyltrifluoroborates (3g and 3p). Under the conditions established, β-trifluoroborato ketones and esters could be coupled to generate 1,4-diketones in moderate to good yields (3f and 3i). Finally, the scalable nature of this coupling protocol was established by performing the reaction on a 4.5 mmol scale (3a). In this reaction, using half of the normal catalyst loadings (1.5 mol % 1 and 3 mol % [Ni(dtbbpy)(H2O)4]Cl2) afforded the desired product in 72% yield.

In conclusion, a visible-light photoredox/Ni electrophilic imide-based acyl transfer cross-coupling reaction has been developed to access a variety of aliphatic ketones in high yields. In this protocol, N-acylpyrrolidine-2,5-diones have been used as electrophilic reagents in transition-metal-catalyzed selective N–C bond cleavage. These imides are readily accessed from the corresponding carboxylic acids and are more stable and more easily handled than the corresponding acyl chlorides or anhydrides. The transformation developed proceeds under extremely mild conditions using visible light without any additive and exhibits tolerance of a variety of functional groups in both coupling partners. This cross-coupling protocol thus represents an expansion of the synergistic photoredox/Ni catalytic paradigm into new electrophile space.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIGMS (R01 GM-113878) and the Bengt Lundqvist Foundation (through the Swedish Chemical Society) by a generous grant to R.A. Frontier Scientific is thanked for the donation of boron compounds used in this investigation. Dr. Rakesh Kohli (University of Pennsylvania) is acknowledged for obtaining HRMS data.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00989.

Experimental procedures, HTE data, compound characterization data, and NMR spectra for all compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Gooßen L. J.; Rodriguez N.; Gooßen K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3100. 10.1002/anie.200704782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dieter R. K. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 4177. 10.1016/S0040-4020(99)00184-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blangetti M.; Rosso H.; Prandi C.; Deagostino A.; Venturello P. Molecules 2013, 18, 1188. 10.3390/molecules18011188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Urawa Y.; Ogura K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 271. 10.1016/S0040-4039(02)02501-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Haddach M.; McCarthy J. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 3109. 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)00476-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Bumagin N. A.; Korolev D. N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 3057. 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)00364-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Gooßen L. J.; Ghosh K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 3458.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kakino R.; Yasumi S.; Shimizu I.; Yamamoto A. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2002, 75, 137. 10.1246/bcsj.75.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Kakino R.; Shimizu I.; Yamamoto A. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2001, 74, 371. 10.1246/bcsj.74.371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Tatamidani H.; Kakiuchi F.; Chatani N. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 3597. 10.1021/ol048513o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tatamidani H.; Yokota K.; Kakiuchi F.; Chatani N. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 5615. 10.1021/jo0492719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Liebeskind L. S.; Srogl J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 11260. 10.1021/ja005613q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Prokopcova H.; Kappe C. O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2276. 10.1002/anie.200802842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Weires N. A.; Baker E. L.; Garg N. K. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 75. 10.1038/nchem.2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li X.; Zou G. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 5089. 10.1039/C5CC00430F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Meng G.; Szostak M. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4364. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lei P.; Meng G.; Szostak M. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 1960. 10.1021/acscatal.6b03616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Liu C.; Liu Y.; Liu R.; Lalancette R.; Szostak R.; Szostak M. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 1434. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Meng G.; Szostak M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 5690. 10.1039/C6OB00084C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Dander J. E.; Garg N. K. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 1413. 10.1021/acscatal.6b03277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Liu C.; Meng G.; Liu Y.; Liu R.; Lalancette R.; Szostak R.; Szostak M. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 4194. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Liu C.; Szostak M. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 10.1002/chem.201605012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Meng G.; Shi S.; Szostak M. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7335. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kemnitz C. R.; Loewen M. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2521. 10.1021/ja0663024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Blanksby S. J.; Ellison G. B. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 255. 10.1021/ar020230d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ouyang K.; Hao W.; Zhang W. X.; Xi Z. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12045. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramaniam S.; Aidhen I. S. Synthesis 2008, 2008, 3707. 10.1055/s-0028-1083226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons B. J.; Weires N. A.; Dander J. E.; Garg N. K. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3176. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tellis J. C.; Primer D. N.; Molander G. A. Science 2014, 345, 433. 10.1126/science.1253647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Primer D. N.; Karakaya I.; Tellis J. C.; Molander G. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2195. 10.1021/ja512946e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Amani J.; Sodagar E.; Molander G. A. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 732. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Amani J.; Molander G. A. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 1856. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe C. L.; Doyle A. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4040. 10.1002/anie.201511438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stache E. E.; Rovis T.; Doyle A. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3679. 10.1002/anie.201700097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a The Amide Linkage: Structural Significance in Chemistry, Biochemistry and Materials Science; Greenberg A., Breneman C. M., Liebman J. F., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: New York, 2003. [Google Scholar]; b Pattabiraman V. R.; Bode J. W. Nature 2011, 480, 471. 10.1038/nature10702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a For more details about the screening through microscale HTE, see the Supporting Information.; b Schmink J. R.; Bellomo A.; Berritt S. Aldrichimica Acta 2013, 46, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman C. A.; Eagles J. B.; Rudahindwa L.; Hamaker C. G.; Hitchcock S. R. Synth. Commun. 2013, 43, 2155. 10.1080/00397911.2012.690061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez O.; Tellis J. C.; Primer D. N.; Molander G. A.; Kozlowski M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4896. 10.1021/ja513079r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanu P.; Mannu A.; Ulgheri F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 1939. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Meltzer P. C.; Butler D.; Deschamps J. R.; Madras B. K. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 1420. 10.1021/jm050797a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bouteiller C.; Becerril-Ortega J.; Marchand P.; Nicole O.; Barre L.; Buisson A.; Perrio C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 1111. 10.1039/b923255a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mori M.; Inouye Y.; Kakisawa H. Chem. Lett. 1989, 18, 1021. 10.1246/cl.1989.1021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Edwards R. L.; Whalley A. J. S. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1979, 803. 10.1039/P19790000803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Kuwahara Y.; Thi My Yen L.; Tominaga Y.; Matsumoto K.; Wada Y. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1982, 46, 2283. 10.1080/00021369.1982.10865413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.