The objective of this study was to determine the prognostic role of complete metabolic response on 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose (18F‐FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography during or following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. The association between 18F‐FDG metabolic parameters (including uptake) and survival outcome, according to breast cancer subtype, was investigated

Keywords: Breast cancer, 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography, Complete metabolic response, Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Prognosis

Abstract

Background.

This study aims to investigate the prognostic role of complete metabolic response (CMR) on interim 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) in patients with breast cancer (BC) receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) according to tumor subtypes and PET timing.

Patients and Methods.

Eighty‐six consecutive patients with stage II/III BC who received PET/CT during or following NAC were included. Time‐dependent receiver operating characteristic analysis and Kaplan‐Meier analysis were used to determine correlation between metabolic parameters and survival outcomes.

Results.

The median follow‐up duration was 71 months. Maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) on an interim PET/CT independently correlated with survival by multivariate analysis (overall survival [OS]: hazard ratio: 1.139, 95% confidence interval: 1.058–1.226, p = .001). By taking PET timing into account, best association of SUVmax with survival was obtained on PET after two to three cycles of NAC (area under the curve [AUC]: 0.941 at 1 year after initiation of NAC) and PET after four to five (AUC: 0.871 at 4 years), while PET after six to eight cycles of NAC had less prognostic value. CMR was obtained in 62% of patients (23/37) with estrogen receptor‐positive (ER+)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2‐negative (HER2−) BC, in 48% (12/25) triple‐negative BC (TNBC), and in 75% (18/24) HER2‐positive (HER2+) tumors. Patients with CMR on an early‐mid PET had 5‐year OS rates of 92% for ER+/HER2− tumors and 80% for TNBC, respectively. Among HER2+ subtype, 89% patients (16/18) with CMR had no relapse.

Conclusion.

CMR indicated a significantly better outcome in BC and may serve as a favorable imaging prognosticator. The Oncologist 2017;22:526–534

Implications for Practice.

This study shows a significantly better outcome for breast cancer (BC) patients who achieved complete metabolic response (CMR) on 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) during neoadjuvant chemotherapy, especially for hormone receptor‐positive tumors and triple negative BC. Moreover, PET/CT performed during an early‐ or mid‐course neoadjuvant therapy is more predictive for long‐term survival outcome than a late PET/CT. These findings support that CMR may serve as a favorable imaging prognosticator for BC and has potential for application to daily clinical practice.

摘要

背景. 本研究旨在按照肿瘤亚型和PET时间评价中期18F‐氟脱氧葡萄糖正电子发射断层扫描/计算机断层扫描(PET/CT)显示的完全代谢缓解(CMR)在接受新辅助化疗(NAC)的乳腺癌(BC)患者中的预后作用。

患者和方法. 连续纳入了86例在NAC治疗期间或治疗后接受PET/CT检查的II/III期BC患者。采用具有时间依赖性的受试者工作特征分析和Kaplan‐Meier分析, 确定代谢参数与生存预后间的相关性。

结果. 中位随访持续时间为71个月。多变量分析显示, 中期PET/CT图像上的最大标准化摄取值(SUVmax)与生存独立相关[总生存(OS):风险比:1.139, 95%置信区间:1.058‐1.226, p =0.001]。将PET时间纳入考虑时, NAC治疗2‐3个周期[开始NAC治疗后1年时的曲线下面积(AUC)为0.941]和4‐5个周期(4年时AUC为0.871)后PET图像上的SUVmax 与生存期之间的相关性最高 , 而NAC治疗6‐8个周期后PET的预后价值有所下降。雌激素受体阳性(ER+)/人类表皮生长因子受体2阴性(HER2‐)BC患者、三阴性BC(TNBC)患者和HER2阳性(HER2+)肿瘤患者中分别有62%(23/37)、48%(12/25)和75%(18/24)达到了CMR。在早‐中期PET显示CMR的ER+/HER2‐肿瘤患者和TNBC患者中, 5年OS率分别为92%和80%。在HER2+亚型中, 89%(16/18)的CMR患者没有复发。

结论.CMR意味着BC的预后显著更佳, 或许可作为有利的影像学预后因子。The Oncologist 2017;22:526–534

对临床实践的提示:本研究表明, 新辅助化疗期间18F‐氟脱氧葡萄糖PET/CT显示达到CMR的BC患者预后显著更佳, 在激素受体阳性肿瘤患者和三阴性BC患者中尤其如此。此外, 新辅助化疗早期或中期进行的PET/CT在长期生存方面的预后价值高于后期PET/CT。上述结果支持CMR在BC患者中可作为有利的影像学预后因子, 且有望应用于日常临床实践

Introduction

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is commonly offered to patients with stage II/III breast cancer (BC) with the goal of delivering early systemic therapy to micrometastatic foci, allowing more patients to undergo breast‐conserving surgery, and assessing tumor response to systemic therapy agents in vivo [1]. Because pathological complete response (pCR) has been validated as a surrogate endpoint of survival in patients receiving NAC for BC, the most widely studied role of 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F‐FDG PET/CT) for response assessment was to predict pCR. However, pCR is seldom attained in estrogen receptor‐positive (ER+) tumors, despite their favorable prognosis. Recent pooled analyses have shown that pCR is not associated with improved survival in less aggressive subtypes such as ER+ BC [2], [3].

18F‐FDG PET provides a reliable measure of tumor burden, as the amount of FDG uptake reflects the number of viable tumor cells. Residual tumor metabolic activity on PET after therapy is an indicator of active disease, whereas a midcourse negative PET is predictive of a successful treatment response [4], [5]. Complete metabolic response (CMR), defined as negative findings on a PET study during or following antitumor therapy, has been proven to predict survival in lymphoma [6], cervical cancer [7], and metastatic BC [8]. The prognostic value of CMR in patients with BC receiving NAC remains uncertain and requires further investigation.

In this study, we aimed to determine the prognostic role of CMR on 18F‐FDG PET/CT during or following NAC in BC patients. Our key objectives were to investigate the association between FDG uptake and survival outcome according to BC subtypes, to evaluate the prognostic performance of CMR with different standards, and to assess the impact of PET timing on the prognostic performance of FDG uptake.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The retrospective protocol was approved by the institutional review board, and informed consent was waived. A search of the PET/CT clinic database identified 218 consecutive patients with BC who underwent 18F‐FDG PET/CT for evaluation of treatment response to NAC between 2003 and 2011. To be eligible for our study, patients had to have histologically confirmed BC stage II or III, must have received NAC, and must have had at least one 18F‐FDG PET/CT scan during or following NAC. Patients all had received anthracycline‐based and/or taxane‐based regimens; trastuzumab was added, as indicated, when human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) was overexpressed or amplified. Patients with ER+ tumors received at least 5 years of endocrine therapy after surgery, and patients with HER2+ tumors received 1 year of adjuvant anti‐HER2 therapy. In patients who had more than one interim PET/CT scans, the first PET/CT study was evaluated. Exclusion criteria are detailed in the flow chart (supplemental online Fig. 1).

For our analysis, pCR was defined as the absence of invasive BC in the breast and axillary nodes irrespective of ductal carcinoma in situ. Event‐free survival (EFS) and BC‐specific overall survival (OS) served as the main outcome measures. EFS was defined as the time from the first day of NAC to the day of disease progression (i.e., loco‐regional or systemic disease recurrence, distant metastasis, death from cancer, or unequivocal imaging evidence of progression). OS was defined as the time from the first day of NAC to the day of cancer‐related death. Because different subtypes of BC show different glucose metabolism and clinical outcomes, analyses were conducted first in the whole study population and then in each of the following BC subtypes: ER‐positive/HER2‐negative (ER+/HER2−), HER2‐positive (HER2+), and triple negative BC (TNBC).

PET/CT Acquisitions and FDG Uptake Measurements

18F‐FDG PET/CT was performed according to a standard clinical protocol. Briefly, the patients were required to fast for at least 6 hours, and blood glucose levels had to be lower than 200 mg/dL. Whole‐body, three‐dimensional PET/CT scans were acquired using a Discovery ST 8, STE 16, RX 16, or VCT 64 PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, http://www.gehealthcare.com) at approximately 60 minutes after intravenous administration of 259–555 MBq of 18F‐FDG. A CT scan (120 kV; 300 mA; pitch, 1.375; slice thickness, 3.75 mm; rotation time, 0.5 second) without contrast enhancement was obtained and used for attenuation correction and diagnostic purposes.

PET/CT images were fused and read on Advantage Workstation 2 (GE Healthcare). Three‐dimensional regions of interest were drawn around the primary tumors and around metastatic lymph nodes when present, then maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmax) were automatically generated. In 49 patients with a baseline PET/CT, the reduction of SUVmax was calculated as: ΔSUVmax = (SUVmax at baseline – SUVmax of the second PET)/SUVmax at baseline * 100%.

PET Timing

Four groups were divided according to their number of courses of NAC administered before PET acquisition: PET2‐3c — patients underwent PET/CT studies after two to three cycles of NAC (n = 17); PET4‐5c — PET/CT was performed after four to five cycles of NAC (n = 28); PET6‐7c — PET/CT after six to seven cycles of NAC (n = 18); PET8c — PET/CT scans after eight cycles of NAC (n = 23).

CMR Definitions

The following three definitions of CMR on PET/CT were compared: CMRbreast as — SUVmax lower than FDG uptake in contralateral breast tissue; CMRliver as — SUVmax below liver FDG uptake; and CMRsuv as — SUVmax lower than a threshold of SUVmax, which is determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and Youden Index. CMR was described within the whole‐body PET/CT scan regardless of CT findings. Conversely, persistence of abnormal FDG uptake (SUVmax higher than the reference settings) was considered CMR not achieved (no‐CMR). Diffuse uptake in the spleen or bone marrow was considered a result of therapy and was not recorded as active disease.

Statistical Analysis

ROC curve analysis was used to define CMRsuv by evaluating the optimal cutoff value of SUVmax to predict disease relapse and cancer‐death. The time‐dependent ROC curve, which estimated the specificity and sensitivity as functions of time [9], was used to evaluate the performance of SUVmax at different timing in predicting disease progression or death. The association between long‐term survival and metabolic parameters was investigated using the univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses. Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis and the log‐rank test were utilized to determine median follow‐up time and 5‐year EFS and OS rates. Negative predictive values (NPVs) and positive predictive values (PPVs) were calculated according to the standard definition [10]. The “survivalROC” package for performance assessment and comparison in the open source statistical software R 3.2.3 were used for the time‐dependent ROC analyses. All other statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, http://www.ibm.com) software. A p value less than .05 based on two‐sided tests was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Eighty‐six consecutive patients receiving NAC for stage II or III BC were included (Table 1). Forty‐nine of them received a baseline PET/CT. Patients’ median age was 51 years old. The median follow‐up duration was 71 months (range, 8–118 months). Twenty‐seven patients had disease recurrence and 23 had died. All patients underwent adjuvant chest wall and/or axillary‐region radiation therapy, except one patient with TNBC who had tumor relapsed on the chest wall, confirmed by ultrasonography‐guided biopsy, 15 days after bilateral mastectomy and removal of left subclavian Port‐A‐Cath.

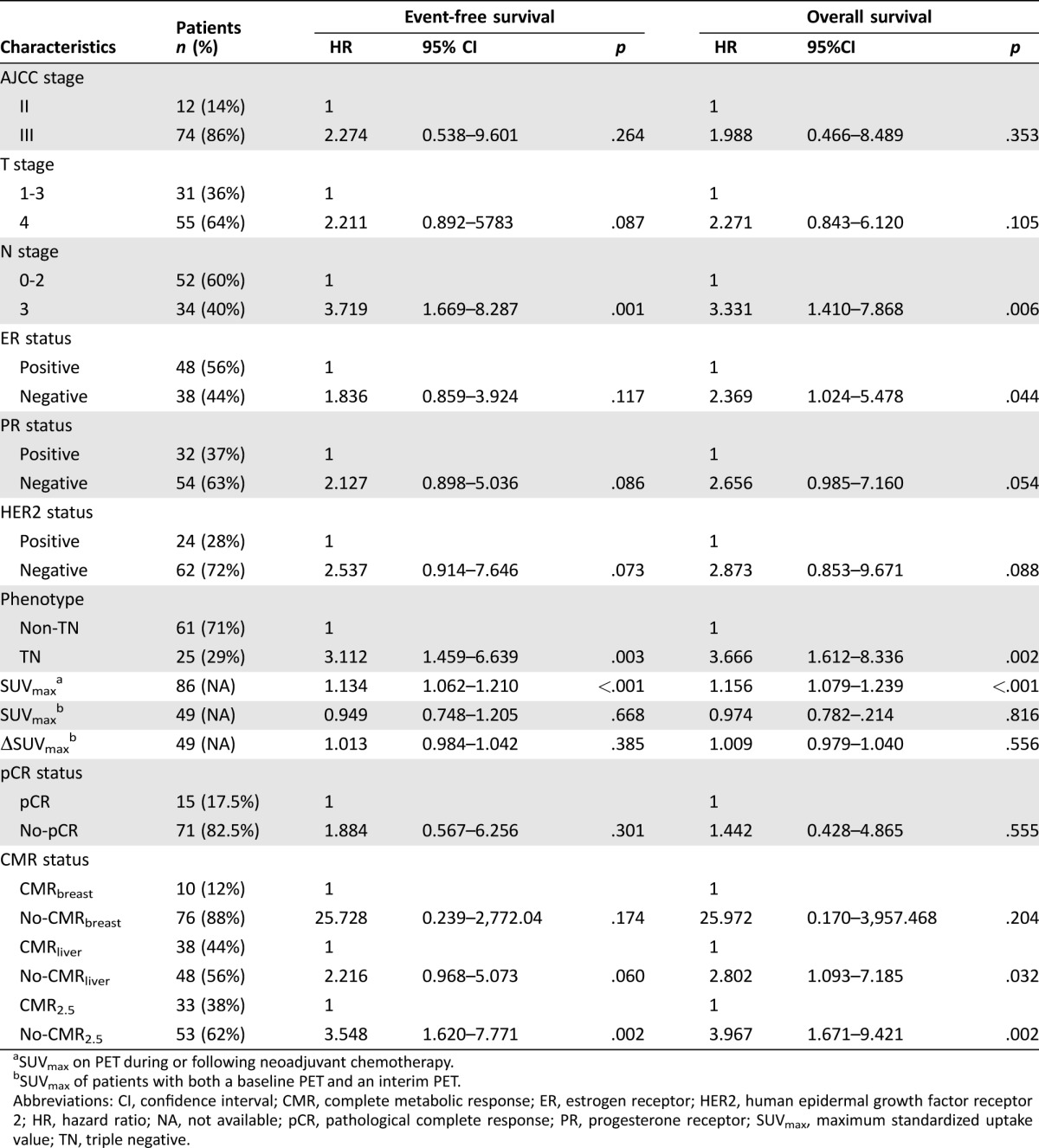

Table 1. Patient characteristics and univariate Cox regression analysis for EFS and OS in the whole study population.

SUVmax on PET during or following neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

SUVmax of patients with both a baseline PET and an interim PET.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMR, complete metabolic response; ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not available; pCR, pathological complete response; PR, progesterone receptor; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value; TN, triple negative.

The Whole Population

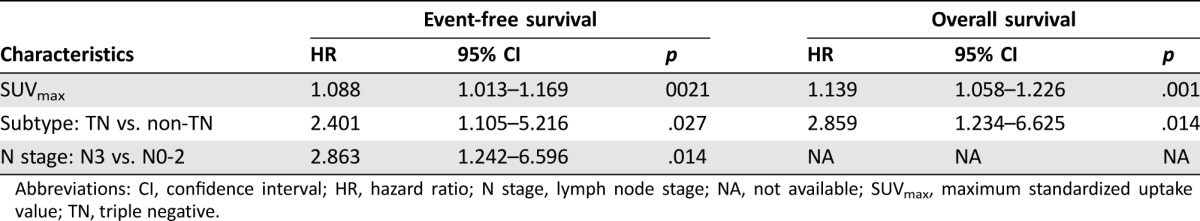

In the whole population with mixed subtypes and PET timing, univariate analysis revealed that SUVmax, lymph node (N) stage, and TNBC were associated with both EFS and OS (Table 1). ER status correlated with OS. SUVmax had the most significant association with survival. After adjusting for other clinicopathological and metabolic parameters by multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, SUVmax, TNBC, and N stage remained significant for predicting EFS, and SUVmax and TNBC had independent predictive value for OS (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariate Cox regression analysis for event‐free survival and overall survival in the whole study population.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; N stage, lymph node stage; NA, not available; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value; TN, triple negative.

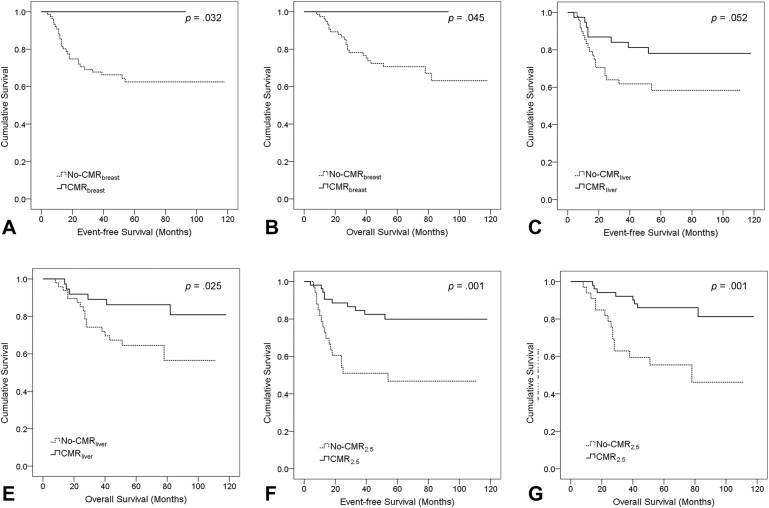

ROC analyses determined that the areas under the curve (AUCs) of SUVmax was 0.692 (p = .007) to predict disease‐related death. The optimal SUVmax cutoff value was 2.5, calculated according to Youden index. Thus, CMRsuv using a threshold of SUVmax of 2.5 was described as CMR2.5. As shown in Table 3, 43 out of 53 patients with CMR2.5 experienced no disease relapse. Ten patients (12%) achieved CMRbreast and none of them experienced disease progression or cancer‐related death. During the follow‐up duration, 30 out of 38 patients with CMRliver remained event‐free. Each definition of CMR stratified high‐ or low‐risk patients effectively (Fig. 1). CMR2.5 offered the strongest correlation with survival.

Table 3. Negative and positive predictive values of pCR and CMRs for overall survival according to tumor subtypes.

Abbreviations: CMR, complete metabolic response; ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; NPV, negative predictive value; pCR, pathological complete response; PPV, positive predictive value; TN, triple negative.

Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier survival plots for event‐free survival and overall survival according to complete metabolic response (CMR) definitions: CMRbreast (A, B), CMRliver (C, D), and CMR2.5 (E, F). Log‐rank p values are provided.

In 49 patients with baseline PET studies, neither the reduction of SUVmax nor an absolute SUVmax during or following treatment predicted survival by univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 1), while CMR2.5 had significant correlation with both EFS (hazard ratio [HR]: 4.374, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.331–14.374, p = .015) and OS (HR: 4.667, 95% CI: 1.247–17.472, p = .022).

PET Timing

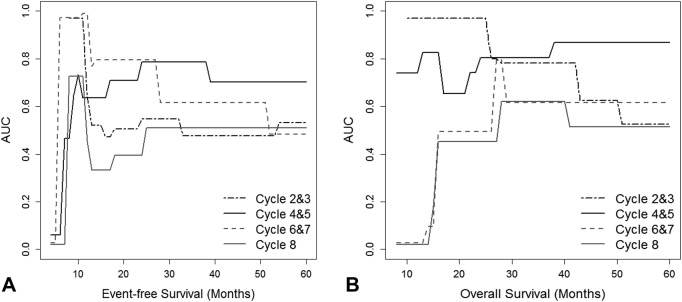

Time‐dependent ROC curve analysis revealed that SUVmax on PET2‐3c and PET4‐5c outperformed SUVmax on PET6‐7c and PET8c to predict survival (Fig. 2). AUCs as a measure of OS prediction was the best with PET2‐3c of 0.941 at 1 year after the initiation of cancer treatment, followed by PET4‐5c of 0.871 at the fourth year. For EFS prediction, AUCs were the best with PET2‐3c of 0.800 at the first year, followed by PET4‐5c of 0.748 at the second year. Optimal cutoff values of SUVmax on PET2‐3c and PET4‐5c were 2.7 and 2.5, respectively, which was similar or the same as the cutoff value in the whole study population.

Figure 2.

Time‐dependent receiver operating characteristic curves as a function of time for maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmax) on positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography of different timing to predict event‐free survival (A) and overall survival (B): black dashed line, SUVmax at PET performed after two to three cycles of NAC; black solid line, SUVmax at PET performed after four to five cycles of NAC; grey dashed line, SUVmax at PET6‐7c; grey solid line, SUVmax at PET8c. Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve.

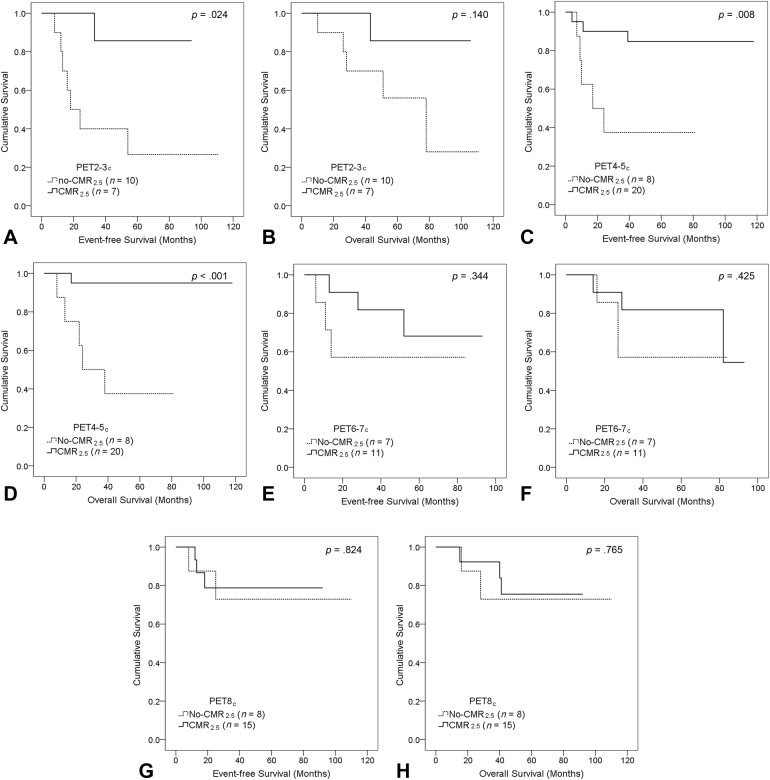

CMR2.5 on PET2‐3c and PET4‐5c resulted in a stronger stratification of patients at high‐ and low‐risk than a late PET (Fig. 3). Five‐year EFS and OS rates for patients with CMR2.5 on PET2‐3c were 86% versus 27% (p = .024) and 86% versus 56% (p = .140), respectively. Five‐year EFS and OS rates for patients with CMR2.5 on PET4‐5c were 85% versus 37.5% (p = .008) and 95% versus 37.5% (p <.001), respectively. No statistical significance in survival was observed between patients who achieved CMR2.5 and those with no‐CMR2.5 either on PET6‐7c or PET8c (Fig. 3E–3H).

Figure 3.

Kaplan‐Meier survival curves of complete metabolic response with a maximum standardized uptake value of 2.5 according to positron emission tomography (PET) timing: PET2‐3c (A, B); PET4‐5c (C, D); PET6‐7c (E, F); PET8c (G, H). Log‐rank p values are provided.

ER+/HER2− Tumors

Thirty‐seven women had an ER+/HER2− tumor, ten of them progressed, and eight had died at the time of analysis. Patients who achieved pCR (n = 1) or CMRbreast (n = 5) remained event‐free. In 36 patients with no‐pCR, 26 (72%) remained event‐free. Twenty‐three patients obtained CMR2.5 and 17 had CMRliver. NPVs and PPVs of pCR and CMR definitions for OS are provided in Table 3. For patients with CMR2.5, 5‐year EFS rates were 81% versus 51% (p = .041) and 5‐year OS rates were 91% versus 67% (p = .027), respectively.

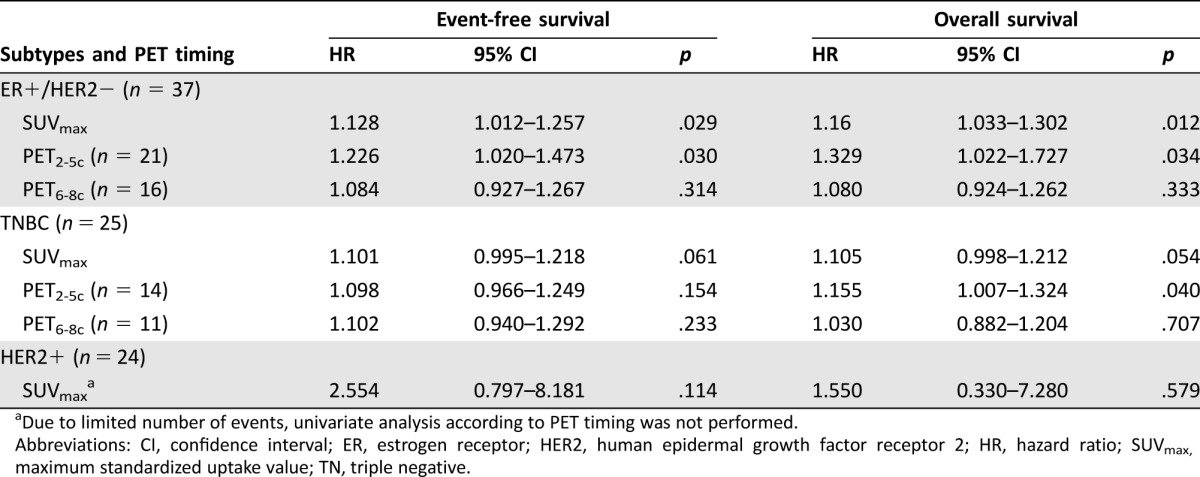

Due to the small number of patients with specific subtypes in each timing group, PET2‐3c and PET4‐5c were combined to form a group of early‐mid PET as PET2‐5c. Similarly, PET6‐7c and PET8c were combined together to form a group of late PET as PET6‐8c. As a result, 21 patients had a PET study after two to five cycles of NAC (PET2‐5c), and 16 patients had a late PET (PET6‐8c). ROC analyses revealed that SUVmax on PET2‐5c had a higher AUC than SUVmax on PET5‐8c for prediction of both disease progression (0.711 versus 0.490) and death (0.794 versus 0.490). Correlation between a residual SUVmax at different PET timing and survival in this subtype is shown in Table 4. Higher SUVmax on an early‐mid PET study indicated inferior survival. CMR2.5 on PET2‐5c demonstrated a clearer distinction between high‐ and low‐risk patients with 5‐year EFS of 85% versus 38% (p = .023) and 5‐year OS of 92% versus 64% (p = .023), respectively.

Table 4. Univariate Cox regression analysis for SUVmax on PET of different timing to predict event‐free survival and overall survival according to tumor subtypes.

Due to limited number of events, univariate analysis according to PET timing was not performed.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hazard ratio; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value; TN, triple negative.

TNBC.

In the group of 25 TNBC, 13 patients had relapse events and 12 died. Three out of four patients with pCR remained event‐free. NPVs and PPVs of each CMR definition are provided in Table 3. Five‐year OS rates for patients with CMR2.5 were 73% versus 31% (p = .037).

Taking PET timing into account, ROC analyses showed that SUVmax on PET2‐5c had a higher AUC than SUVmax on PET5‐8c for prediction of death (0.816 versus 0.667) and a slightly better AUC to predict disease progression (0.687 versus 0.667). As shown in Table 4, SUVmax on an early‐mid PET had a stronger association with OS (HR: 1.155, 95% CI: 1.007–1.324, p = .040), as compared with a late PET (HR: 1.030, 95% CI: 0.882–1.204, p = .707). Although statistical significance was not reached, due to the small number of patients, 5‐year OS of patients with CMR2.5 on PET2‐5c was 80% versus 33% (p = .133). In group of PET6‐8c, 5‐year OS rates of CMR2.5 was 60% versus 40% (p = .568).

HER2+ Subtype

Twenty‐four patients had HER2+ tumors. Four patients relapsed and three died. During follow‐up, eight out of ten patients with pCR had no disease‐related death. Sixteen out of 18 patients with CMR2.5 had no relapse (Table 3). A residual SUVmax had no significant correlation with either EFS or OS. Although nonsignificant, a trend towards longer survival in HER2+ patients who achieved CMR2.5 was observed, with 5‐year EFS rates of 88% versus 67% (p = .197). Given the small number of relapse and death events, analyses according to PET timing was not performed.

Discussion

With a median follow‐up duration of 71 months, FDG uptake on a single PET/CT independently correlated with survival outcomes by multivariate analysis in BC patients receiving NAC. CMR during or following NAC predicted a favorable outcome. This study also observed that an early or midcourse PET/CT had a higher predictive value for survival compared with a late PET.

CMR during or following chemotherapy can powerfully stratify for survival in patients with metastatic BC [8], [11]. In BC patients with mixed tumor subtypes receiving NAC, Emmering et al. [12] presented that failure to achieve a negative preoperative PET indicated 2.5 times higher risk of disease recurrence. In this study, we first compared the prognostic value of three different definitions of CMR in the whole cohort, using the contralateral breast tissue, liver background, or a cutoff value of SUV as reference settings. We found each CMR definition had a role in prognosis. CMRbreast predicted an excellent prognosis (NPV of 100%), and CMR2.5 stratified for survival most powerfully (Fig. 1).

Because BC with different subtypes has different glucose metabolism, treatment response, and clinical outcomes [13], [14], we aimed to investigate the prognostic role of residual FDG uptake and CMR during or following NAC according to tumor subtypes and PET timing. In ER+/HER2− BC, previous studies have proven the prognostic value of change in SUVmax after 1 or 2 courses of NAC [15], [16], [17]. However, the cutoff values of SUV reduction varied greatly across these studies, from 12% to 50%, making interpretation of scan results challenging in daily clinical practice. Comparing with change in SUVmax, Groheux et al. [16] found that an absolute SUVmax after two cycles of NAC had a stronger association with survival and adversely affected prognosis for ER+/HER2− BC. Our data are in agreement and showed SUVmax and CMR during or following NAC significantly correlated with long‐term survival in this subtype. As opposed to low rate of pCR (3%), CMR2.5 was achieved at a frequency of 62% in ER+/HER2− tumors. After taking PET timing into account, both SUVmax and CMR2.5 on an early‐mid PET showed higher predictive value than a late PET in this subtype (Table 4). Thus, SUVmax and CMR2.5 on an early‐mid PET might serve as imaging prognostic factors in ER+/HER2− BC.

In aggressive tumor subtypes (TNBC or HER2+), our findings on the prognostic role of PET parameter confirm and extend on previous reports. Despite contradicting results, the ability of SUV reduction to predict pCR [18], [19], [20], [21] and survival [22], [23], [24] has been investigated in TNBC and HER2+ tumors. However, limited information is available on the relationship between survival and residual FDG uptake during or following NAC in these subtypes. In this study, an absolute residual SUVmax showed only marginal or no relation with survival for TNBC or HER2+ tumors. After grouping by PET timing, however, higher SUVmax on PET2‐5c suggested inferior OS in TNBC. Although no conclusion was drawn regarding CMR, a table in a study by Groheux et al. [24] containing 20 TNBC patients recorded that five out of six (83%) patients with an absolute SUVmax below 2.5 after two cycles of NAC had no relapse. Our results are in agreement; approximately 80% of TNBC patients who achieved an early CMR2.5 during NAC did not die of cancer. We also found evidence on the prognostic role of CMR2.5 in the HER2+ subtype, showing near 90% of patients with CMR experienced no relapse.

Our study adds to the accumulating evidence that the correlation between metabolic parameters of PET and survival varied by PET timing. Several studies compared PET performance at different time points and found that an early assessment after one or two cycles of treatment is more predictive [25], whereas others proved that PET at midcourse [19], [26] or prior to surgery might be optimal [27]. This study differed from the previous studies, which focused on the role of change in FDG uptake between sequential PET scans in patients with mixed subtypes. We assessed the impact of PET timing on the prognostic performance of SUV on a single interim or preoperative PET according to BC subtypes. Time‐dependent ROC analysis allowed comparison of observations at different time points [9] and revealed that AUC as a measure of EFS or OS prediction was the highest with PET2‐3c by the first 1 or 2 years, while it was much lower at later follow‐up times. PET4‐5c, however, appeared to have a higher AUC for predicting both survival outcomes at later time points (Fig. 2). Thus, FDG uptake on PET after two to three cycles of NAC might be more accurate at identifying patients who relapse or die within the first 1 or 2 years, while PET after four to five cycles of NAC appears to provide improved discrimination for survival at later follow‐up times. PET performed after six to eight cycles of NAC was less prognostic. Furthermore, CMR on an early or midcourse PET more powerfully stratified for survival both in the whole population and in groups of BC subtypes. The results are in concordance with the theory of “the kinetics of tumor cell killing and relation to PET” by Kasamon et al. [5], which has been widely implemented on treatment response assessment in lymphoma. They indicated that a midcourse negative PET study might represent an absence of cancer cells or minimal residual disease that would lead to cure after chemotherapy, while a negative scan later or at the end of therapy may have less value in distinguishing between an absence of tumor and an insufficient tumor cell killing required to achieve a cure. In our study, a residual FDG uptake at a late PET failed to predict survival both in the whole cohort and among different tumor subtypes (Fig. 3).

Our study has limitations, mostly related to its retrospective nature. First, the sample size was small and the patient population was heterogeneous. Despite the small number, our cohort had representative distribution with subtype distribution and pCR frequency similar to other reports [2], [19], [22]. Second, PET timing was variable. Due to heterogeneous PET timing and limited number of patients who had received a baseline PET in our study, the correlation between survival and the reduction of SUVmax or residual FDG uptake during or following NAC could not be validated. Despite this, after taking account of PET timing, our findings confirmed the theory of “the kinetics of tumor cell killing and relation to PET,” showing that FDG uptake and CMR on an early or midcourse PET might reflect tumor sensitivity to certain regimens of NAC and had higher prognostic value than a late PET. An additional limitation was that the ROC analysis and Youden index were used to define the cutoff value of SUVmax 2.5 as CMRsuv, and this method could overestimate the predictive performance of CMR2.5. Hence, CMRliver and/or CMRbreast should be interpreted as well, especially in aggressive subtypes such as TNBC. Prospective studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm the findings.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings suggest that FDG uptake on a single PET/CT after initiation of NAC was an independent prognostic factor for long‐term survival in BC patients. An early or midcourse CMR indicated an excellent prognosis, with 5‐year OS rates of 92% for ER+/HER2− tumor and 80% for TNBC, respectively.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Fund (51233007, 81271612, and 81401439), John Dunn Research Foundation, National Institute of Health Grant (NIH U54CA149196), TT & WF Chao Foundation Endowment, and the James E. Anderson Distinguished Professorship Endowment, which is an MD Anderson Cancer Center support grant from the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA016672).

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Sara Sheikhbahaei, Tyler J. Trahan, Jennifer Xiao et al. FDG‐PET/CT and MRI for Evaluation of Pathologic Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients With Breast Cancer: A Meta‐Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. The Oncologist 2016;21:931–939.

Implications for Practice: The timing of therapy assessment imaging exerts a major influence on overall estimates of diagnostic accuracy. 18F‐fluoro‐2‐glucose‐positron emission tomography (FDG‐PET)/computed tomography (CT) imaging outperformed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in intra‐neoadjuvant chemotherapy assessment with fairly similar pooled sensitivity and higher specificity. However, MRI appeared to be more accurate than FDG‐PET/CT in predicting pathologic response when used in the post‐therapy setting.

Author Contributions

Concept/Design: Suyun Chen, Nuhad K. Ibrahim, Yuanqing Yan, Stephen T. Wong, Hui Wang, Franklin C. Wong

Provision of study material or patients: Suyun Chen, Nuhad K. Ibrahim, Hui Wang, Franklin C. Wong

Collection and/or assembly of data: Suyun Chen, Nuhad K. Ibrahim, Yuanqing Yan, Stephen T. Wong, Franklin C. Wong

Data analysis and interpretation: Suyun Chen, Nuhad K. Ibrahim, Yuanqing Yan, Stephen T. Wong, Hui Wang, Franklin C. Wong

Manuscript writing: Suyun Chen, Nuhad K. Ibrahim, Yuanqing Yan, Stephen T. Wong, Hui Wang, Franklin C. Wong

Final approval of manuscript: Suyun Chen, Nuhad K. Ibrahim, Yuanqing Yan, Stephen T. Wong, Hui Wang, Franklin C. Wong

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1. Gralow JR, Burstein HJ, Wood W et al. Preoperative therapy in invasive breast cancer: Pathologic assessment and systemic therapy issues in operable disease. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:814–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M et al. Pathological complete response and long‐term clinical benefit in breast cancer: The CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet 2014;384:164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berruti A, Amoroso V, Gallo F et al. Pathologic complete response as a potential surrogate for the clinical outcome in patients with breast cancer after neoadjuvant therapy: A meta‐regression of 29 randomized prospective studies. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3883–3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Avril S, Muzic RF Jr., Plecha D et al. 18F‐FDG PET/CT for monitoring of treatment response in breast cancer. J Nucl Med 2016;57 (suppl 1):34S–39S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kasamon YL, Jones RJ, Wahl RL. Integrating PET and PET/CT into the risk‐adapted therapy of lymphoma. J Nucl Med 2007;48 (suppl 1):19S–27S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of hodgkin and non‐hodgkin lymphoma: The lugano classification. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3059–3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schwarz JK, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F et al. Association of posttherapy positron emission tomography with tumor response and survival in cervical carcinoma. JAMA 2007;298:2289–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cachin F, Prince HM, Hogg A et al. Powerful prognostic stratification by [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic breast cancer treated with high‐dose chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3026–3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heagerty PJ, Lumley T, Pepe MS. Time‐dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics 2000;56:337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Altman DG and Bland JM. Diagnostic tests 2: Predictive values. BMJ 1994;309:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Giorgi U, Valero V, Rohren E et al. Circulating tumor cells and [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for outcome prediction in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3303–3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Emmering J, Krak NC, Van der Hoeven JJ et al. Preoperative [18F] FDG‐PET after chemotherapy in locally advanced breast cancer: Prognostic value as compared with histopathology. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1573–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Humbert O, Cochet A, Coudert B et al. Role of positron emission tomography for the monitoring of response to therapy in breast cancer. The Oncologist 2015;20:94–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Groheux D, Giacchetti S, Espie M et al. Early monitoring of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer with 18F‐FDG PET/CT: Defining a clinical aim. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;38:419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zucchini G, Quercia S, Zamagni C et al. Potential utility of early metabolic response by 18F‐2‐fluoro‐2‐deoxy‐D‐glucose‐positron emission tomography/computed tomography in a selected group of breast cancer patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1539–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Groheux D, Sanna A, Majdoub M et al. Baseline tumor 18F‐FDG uptake and modifications after 2 cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy are prognostic of outcome in ER+/HER2‐ breast cancer. J Nucl Med 2015;56:824–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Humbert O, Berriolo‐Riedinger A, Cochet A et al. Prognostic relevance at 5 years of the early monitoring of neoadjuvant chemotherapy using (18)F‐FDG PET in luminal HER2‐negative breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2014;41:416–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Groheux D, Majdoub M, Sanna A et al. Early metabolic response to neoadjuvant treatment: FDG PET/CT criteria according to breast cancer subtype. Radiology 2015;277:358–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koolen BB, Pengel KE, Wesseling J et al. Sequential (18)F‐FDG PET/CT for early prediction of complete pathological response in breast and axilla during neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2014;41:32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koolen BB, Pengel KE, Wesseling J et al. FDG PET/CT during neoadjuvant chemotherapy may predict response in ER‐positive/HER2‐negative and triple negative, but not in HER2‐positive breast cancer. Breast 2013;22:691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheng J, Wang Y, Mo M et al. 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT after two cycles of neoadjuvant therapy may predict response in HER2‐negative, but not in HER2‐positive breast cancer. Oncotarget 2015;6:29388–29395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Groheux D, Biard L, Giacchetti S et al. 18F‐FDG PET/CT for the early evaluation of response to neoadjuvant treatment in triple‐negative breast cancer: Influence of the chemotherapy regimen. J Nucl Med 2016;57:536–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Groheux D, Hindie E, Giacchetti S et al. Early assessment with 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography can help predict the outcome of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:1864–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Groheux D, Hindie E, Giacchetti S et al. Triple‐negative breast cancer: Early assessment with 18F‐FDG PET/CT during neoadjuvant chemotherapy identifies patients who are unlikely to achieve a pathologic complete response and are at a high risk of early relapse. J Nucl Med 2012;53:249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schwarz‐Dose J, Untch M, Tiling R et al. Monitoring primary systemic therapy of large and locally advanced breast cancer by using sequential positron emission tomography imaging with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Couturier O, Jerusalem G, N'Guyen JM et al. Sequential positron emission tomography using [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose for monitoring response to chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:6437–6443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Champion L, Lerebours F, Alberini JL et al. 18F‐FDG PET/CT to predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and prognosis in inflammatory breast cancer. J Nucl Med 2015;56:1315–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.