Abstract

Ascaris suum provides a powerful model for studying parasitic nematodes, including individual tissues such as the intestine, an established target for anthelmintic treatments. Here, we add a valuable experimental component to our existing functional, proteomic, transcriptomic and phylogenomic studies of the Ascaris suum intestine, by developing a method to manipulate intestinal cell functions via direct delivery of experimental treatments (in this case, double-stranded (ds)RNA) to the apical intestinal membrane. We developed an intestinal perfusion method for direct, controlled delivery of dsRNA/heterogeneous small interfering (hsi) RNA into the intestinal lumen for experimentation. RNA-Seq (22 samples) was used to assess influences of the method on global intestinal gene expression. Successful mRNA-specific knockdown in intestinal cells of adult A. suum was accomplished with this new experimental method. Global transcriptional profiling confirmed that targeted transcripts were knocked down more significantly than any others, with only 12 (0.07% of all genes) or 238 (1.3%) off-target gene transcripts consistently differentially regulated by dsRNA treatment or the perfusion experimental design, respectively (after 24 h). The system supports controlled, effective delivery of treatments (dsRNA/hsiRNA) to the apical intestinal membrane with relatively minor off-target effects, and builds on our experimental model to dissect A. suum intestinal cell functions with broad relevance to parasitic nematodes.

Keywords: Nematode, A. suum, RNAi, Intestine, Methodology, dsRNA

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Parasitic nematodes are estimated to infect nearly 2 billion people across the globe (Holden-Dye and Walker, 2007). They also infect numerous agricultural species, affecting food production, which is of critical importance to underdeveloped regions of the world. The small size, biological complexity, and experimentally intractable nature of most parasitic nematodes hinder research aimed at elucidating essential functions in these pathogens. However, recently developed ‘omics’ resources (Jex et al., 2011; Jasmer et al., 2014; Rosa et al., 2014, 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2016) and experimental capabilities (Chen et al., 2011; Jasmer et al., 2014; McCoy et al., 2015) established for the large round worm of swine and humans, Ascaris suum, continue to build on this global pathogen’s importance as a facile model system to conduct research on essential cellular functions in parasitic nematodes.

Importantly, the unusually large size of adult A. suum (up to 40 cm in length) provides valuable support to research into specific tissues with relevance to anthelmintic therapies. The nematode intestine, for example, is a confirmed target of anthelmintic strategies encompassing immune-, pharmaco- and toxico- therapies (Jasmer et al., 2000; Bethony et al., 2006; Hu and Aroian, 2012). Nevertheless, limitations to knowledge and experimental methods have impeded research on this and other tissues of parasitic nematodes. Multiomics databases have been established for the intestine and other tissues of A. suum (Jasmer et al., 2014; Rosa et al., 2014; Gao et al., 2016), including proteomics distinguishing multiple intestinal cell compartments (Rosa et al., 2015) and pan-Nematoda intestinal transcriptome comparisons (Wang et al., 2015). This knowledge base helps to guide experimental design and interpret results from studies using the model organism A. suum.

Here we advance the A. suum experimental model by extending our intestinal cannulation-perfusion method (used in previous proteomic research (Jasmer et al., 2014; Rosa et al., 2015)) to directly manipulate intestinal cells in situ by using controlled delivery of experimental treatments. No comparable methods are known to exist for controlled delivery of this kind to nematode intestinal cells. Controlled delivery of double-stranded (ds)RNA treatments to the intestinal lumen and apical intestinal membrane was performed to achieve knockdown of target intestinal cell transcripts. The intestine is one of the most sensitive tissues to dsRNA disruption when it is fed to other nematode species (Selkirk et al., 2012), and oral dsRNA delivery may have therapeutic applications to treat infections. To better clarify components of this experimental method, we differentiated effects of the basic methodology and dsRNA treatments on the global intestinal transcriptome. Collectively, the results validate a valuable method that has application to elucidate essential intestinal cell functions with potential pan-Nematoda relevance.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal experimentation guidelines

The research involving use of swine was reviewed and approved by the Washington State University (USA) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, protocol #04097, approved from 12/2010 to present. Guidelines are provided by the Federal Animal Welfare Act, USA.

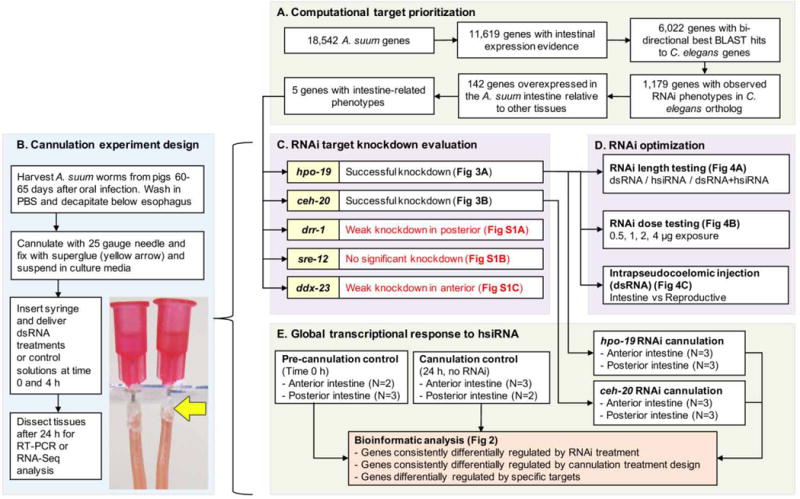

2.2. Computational target prioritization

Prioritization identified A. suum genes with the highest probability of inducing specific target transcript knockdown, and with broad conservation among nematodes (Fig. 1A). Adult female and male A. suum intestinal RNA-seq datasets (Rosa et al., 2014) were used to identify genes with intestinal expression (11,619 of 18,542 A. suum genes). Bi-directional BLAST matches with Caenorhabditis elegans and WormMart RNA interference (RNAi) phenotype annotation data (WS230) (Harris et al., 2014) identified 1,179 intestine-expressed genes with “observed” RNAi phenotypes, 142 genes of which were overexpressed in the intestine relative to other tissues (Rosa et al., 2014). Of these, RNAi phenotype descriptions related to intestine functions were searched, identifying five targets: (i) GS_08011 (hpo-19) and (ii) GS_15745 (ceh-20), annotated with “receptor mediated endocytosis defective” (WormBasePhenotype:0001425), previously associated with intestinal function and development (Hadwiger et al., 2010); (iii) GS_00114 (drr-1), annotated with “mitochondrial membrane potential reduced” (WBP:0001893); (iv) GS_05582 (ddx-23), annotated with “excess intestinal cells” (WBP:0001636) and (v) GS_00255 (sre-12), annotated with “intestinal vacuole” (WBP:0001428). Proteins encoded by each of these genes have predicted orthologs that are broadly conserved across nematode groups, or, in the cases of ddx-23 and sre-12, universally conserved (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Overall experimentation workflow. Computational target prioritization, including utilizing existing Caenorhabditis elegans datasets (A) was used to identify target Ascaris suum genes for use in the cannulation experiment (B). Priority targets from RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown experiments (C) were used to optimize the experimentation (D). Finally, global transcriptome responses to heterogeneous small interfering dsRNA (hsiRNA) was performed to identify gene sets of interest.

Table 1.

Descriptions and real-time (RT)-PCR primers for target genes.

| Gene type | Ascaris suum gene ID | Gene Short Name (based on Caenorhabditis elegans homology) | Target phylogenetic/intestinal conservation (Wang et al., 2015) | Gene region | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target (RT-PCR and RNA-Seq) | GS_08011 | hpo-19 (Hypersensitive to POre-forming toxin) | Universally conserved | 5′ | AGAGAACCTGCTGTGGCTTT | GAAACCTGCGTGTATCATGG |

| 3′ | AGCACCTACCCGTACCAAAC | ACACATGCGAAGTTGACCAT | ||||

| hsiRNA | ACAGTGCTGCGCTTATAGCA | GCGATCATACCCACGTTTTT | ||||

| GS_15745 | ceh-20 (C. elegans homeodomain protein) | Conserved among all nematodes | 5′ | TATGCTTGTAGCCGAAGGTG | TGTTGCGTGAACTCTTGACA | |

| 3′ | TGGACAAGATCTAGCGCATC | CGCCACTTACTGATGGAAGA | ||||

| hsiRNA | CGCTTAACGACCTTCTCTCG | TCATCACTGCCTCACAGGTC | ||||

| Target (RT-PCR) | GS_00114 | drr-1 (Dietary Restriction Response) | Conserved among clade V nematodes | Center | TGGGATTGTGTGGTTTATCG | CCATGGTATAGATGCGTTGC |

| hsiRNA | TAACGATTTGCCTCGGTTCT | AGACTGGTAGGGCGTCTCCT | ||||

| GS_05582 | ddx-23 (DEAD boX helicase) | Universally conserved | 5′ | CTCAAGAGCAGAGCGTGAAG | TCGTTTTCCATCTTGGATGA | |

| 3′ | TGGCAGCAAAGATATTCTCG | TATCGCTTTGCCATGCTTAC | ||||

| hsiRNA | CGATCGAGGAGTTGATAGCC | CAGATGTGTCCTCTCCAGCA | ||||

| GS_00255 | sre-12 (Serpentine Receptor, class E) | Universally conserved | 5′ | CAAATGGGAACGTGAAATTG | CGGCGGAGGTAATATTTTGT | |

| 3′ | AATTGCTGAAGGCACACAAG | GTACGGTGAATGGAGCACAC | ||||

| hsiRNA | TCGAGAGTCTGTACGCGATG | GGTCGTTCAGGTGTTCCTTG | ||||

| Off-target control | GS_00705 | Off-target control | – | 5′ | AGCCGATTCTCTTCGTGATT | ACCATCCGGGTCCATAATAA |

| Housekeeping | GS_01032 | Housekeeping | Universally conserved | 5′ | CTACGAATCGTTTCCGGATT | TGGCTTATCAACACCCTCAA |

hsiRNA, heterogeneous small interfering double-stranded RNA.

2.3. Target gene cloning and preparation of dsRNA

Gene-specific primers for five A. suum intestinal genes (Table 1) were used in PCR amplification reactions with 10 ng of adult female A. suum intestinal cDNA as previously described (Wang et al., 2015). Resulting gene segments were cloned into the TOPO dual promoter plasmid (Invitrogen, USA). dsRNA was generated by PCR amplification of sequence-confirmed inserts with primers that included T7 adapters, followed by purification (PCR purification kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and in vitro transcription (HiScribe T7, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). dsRNA was precipitated with isopropanol and NaOAc, and resuspended in 120 μL of nuclease free water. To generate heterogeneous small interfering dsRNA (hsiRNA), 60 μg of each dsRNA product was digested with Shortcut RNase (Landmann et al., 2012). These preparations were ethanol precipitated and solubilized in 50 μL of nuclease-free water.

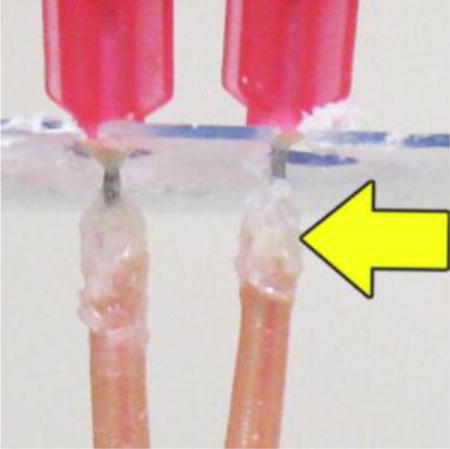

2.4. Perfusion of the A. suum intestine for dsRNA delivery

Adult female A. suum were collected from pigs after 60–65 days oral infection with infective eggs (Rosa et al., 2014), decapitated just below the esophagus and fitted with a blunt-end 25 gauge needle inserted into the intestinal lumen, which was superglued in place (Jasmer et al., 2014). A tuberculin syringe was attached to the needle via the syringe hub to deliver experimental treatments. In contrast to previous perfusion experiments (Jasmer et al., 2014), the posterior end of worms remained intact to conduct dsRNA experiments. Cannulas were slid into a slot cut into a plastic microscope slide, allowing suspension and culture of worms (three for each treatment) in a 250 ml oak ridge tube filled with PBS (37°C) for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 1B).

Perfusion of the intestine with dsRNA or hsiRNA was performed by adding prescribed quantities (0.5 to 4.0 μg) to 100 μl of DMEM culture medium (pH 7.4, 37°C) and injecting with the tuberculin syringe, followed by a second injection with the same quantity 4 h later. Intestinal tissues were dissected from treated worms, split into anterior and posterior halves and processed to obtain RNA 24 h after the initial injection. Control worms received a volume-matched injection of DMEM only.

Intrapseudocoelomic (IP) injection of dsRNA or hsiRNA was performed on intact worms (intact head and tail) using a tuberculin syringe, with the unaltered needle (not blunt-ended) inserted into the pseudocoelom at the approximate midpoint of the body of female A. suum (and a second injection 4 h after the first). IP injected worms were cultured in 250 ml of PBS (37° C) for 24 h after the initial injection and prior to tissue sampling and RNA preparation. Control worms received injection of DMEM only.

2.5. Quantifying gene expression and knockdown by RT-PCR

Five hundred ng of total RNA was used as template in cDNA synthesis reactions using qScript cDNA SuperMix (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). cDNA was purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Ten ng of cDNA template were used in real-time (RT) PCRs with PowerSYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies, USA) in 25 μL reactions and 10 pm of each primer (Table 1). Cycle threshold (CT) values were determined using the Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR System.

The relative abundance (fold change) of targeted genes in treated versus non-treated samples was calculated relative to housekeeping gene expression and untreated control sample expression using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008), using the average of 5′ and 3′ primer CT values, with triplicate biological replicates, against housekeeping gene GS_01032 (identified due to its relatively consistent and high expression across non-reproductive tissues (Rosa et al., 2014) and life cycle stages (Jex et al., 2011)). The off-target control gene GS_00705 had high and consistent expression across all intestinal samples (Rosa et al., 2014). Two-tailed T-tests with unequal variance comparing the experimental and control ΔCT values were used to determine significant differential regulation (Yuan et al., 2006).

2.6. Analysis of RNA-Seq datasets

RNA-Seq was performed for 24 samples from both the anterior and posterior intestine, at time 0 and 24 h after treatment (including hsiRNA/control treatment and cannulation setup), for diluent controls and treatment with hpo-19 and ceh-20 hsiRNA, in triplicate (with two replicates failing quality testing post-sequencing: anterior control 0 h, and posterior control 24 h). Paired-end cDNA libraries were generated according to standard protocols and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. Raw reads were submitted to the GenBank sequence read archive (SRA) under BioProject PRJNA167264 (Supplementary Table S1). Reads were processed for quality, complexity and contamination as previously described (McNulty et al., 2014), and were aligned to the genome assembly (Jex et al., 2011) using Tophat2 (version 2.0.8, default parameters (Kim et al., 2013)) and counted using HTSeq-Count (Anders et al., 2015).

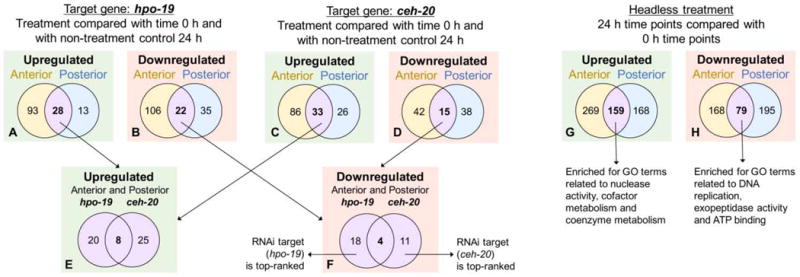

Differential gene expression analysis was carried out using the DESeq2 package, version 1.6.1 (Anders and Huber, 2010) (Fig. 2). A conservative differential adjusted P value cutoff of 0.01 provided a confident threshold which makes the final gene sets consistent with other statistical packages such as EdgeR (Kvam et al., 2012). To quantify the effect of treatment (Fig. 2A–D), DESeq2 compared treatment samples with both time 0 h and 24 h control samples, with the secondary factor of time to account for variability between the control groups. Gene sets in Fig. 2E, F were identified by intersecting gene lists from Fig. 2A–D. Similarly, gene differential expression changes in response to the cannulation experimental method (Fig. 2G, H) compared the 0 h timepoint with all 24 h timepoints, while controlling for the treatments (control, hpo-19 hsiRNA, and ceh-20 hsiRNA) as secondary factors. InterProScan (Jones et al., 2014) annotated Gene Ontology (GO) terms to genes (Consortium, 2013) (as previously described (Rosa et al., 2014)), and GO term enrichment among subsets of genes was determined using GOstats (P≤0.01, minimum of three genes) (Falcon and Gentleman, 2007). All expression data, differential expression data, and functional annotations per gene (retrieved from previous studies (Issa et al., 2005; Nunes et al., 2013)) are in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3.

Fig. 2.

Counts of genes differentially regulated by double-stranded (ds)RNA treatment (and not control) between 0 and 24 h in both the anterior and posterior Ascaris suum intestine. Genes (A) upregulated and (B) downregulated by hpo-19 RNA interference (RNAi) treatment and not control, in the anterior and posterior intestine are identified. Genes (C) upregulated and (D) downregulated by ceh-20 RNAi treatment and not control, in the anterior and posterior intestine are identified. Genes (E) upregulated (F) downregulated by RNAi treatment and not control in both the anterior and posterior intestine are compared for the two target genes. GO, Gene Ontology.

3. Results

The efficacy of mRNA transcript knockdown was determined in intestinal cells of A. suum by direct delivery of dsRNA to the intestinal lumen in cannulated adult female worms. Once efficacy was determined, the effects of dsRNA perfusion of the intestine on global transcript expression by intestinal cells were determined.

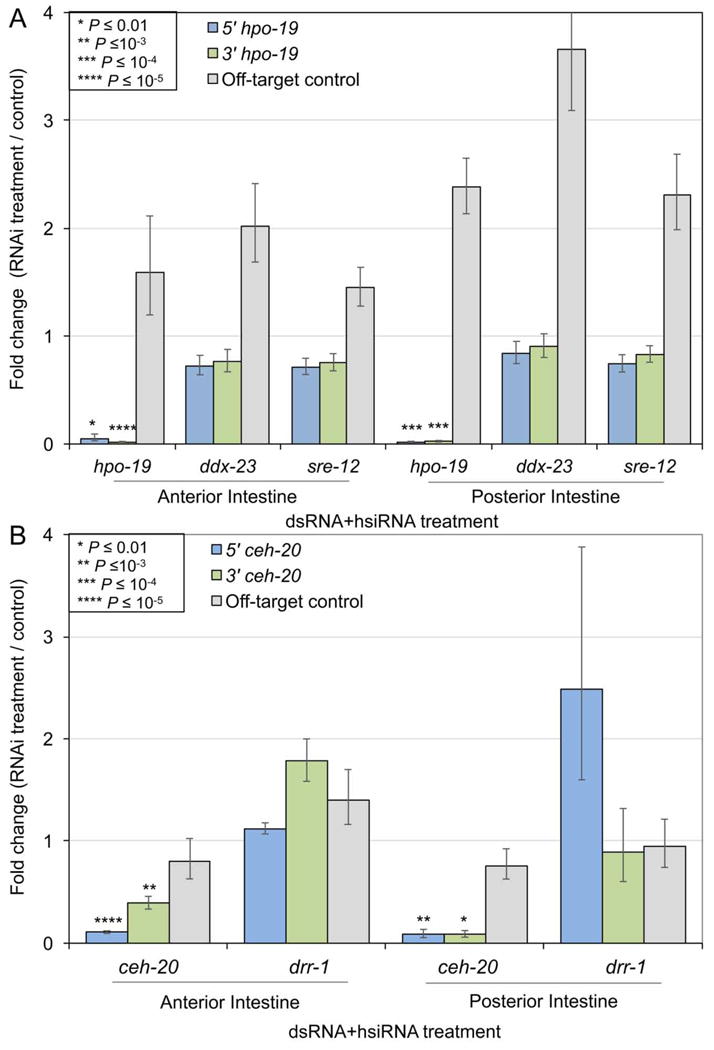

3.1. Confirmation of target-specific dsRNA knockdown in adult A. suum

Five A. suum genes with high intestinal expression and predicted RNAi phenotypes were prioritized for targeting (see Section 2). A mixture of both dsRNA (~500 bp) and hsiRNA (~20 bp) for each gene (2 μg of each per injection) was included, since hsiRNA may confer enhanced efficacy (Landmann et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015). RT-PCR was performed (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1, Table 1), and two target transcripts (hpo-19 and ceh-20) demonstrated highly significant knockdown in both anterior and posterior halves of the intestine (Fig. 3) within 24 h. Variable knockdown was observed for the other target transcripts: ddx-23 was significant only in the anterior intestine (Supplementary Fig. S1A), drr-1 was significant only in the posterior intestine (Supplementary Fig. S1B), and no significant knockdown was observed for sre-12 (Supplementary Fig. S1C). For sre-12, a BLAST search identified probable off-target hits for the amplified hsiRNA sequences (100% match across 22 and 24bp for GS_01101 and GS_17607, respectively), suggesting possible competition for RNAi machinery (Jackson and Linsley, 2010) and interference with efficient knockdown. The off-target control gene (GS_00705) was not significantly downregulated in any of the experiments (Figs. 1C,D, 3 and 4; Supplementary Fig. S1). Variable transcript knockdown was also observed in other A. suum tissues injected IP with dsRNA in a previous study (McCoy et al., 2015), which may reflect differences in cellular uptake, relative abundances of target transcripts, or insufficient duration of the experiment (although 24 h was sufficient for other targets here).

Fig. 3.

Real-time (RT) PCR results in the anterior and posterior Ascaris suum intestine, after performing double-stranded (ds)RNA + heterogeneous small interfering dsRNA (hsiRNA) RNA interference (RNAi) treatment against the target genes (A) hpo-19 and (B) ceh-20. Off-target genes ddx-23, sre-12 and drr-1 were used as controls. Error bars represent S.D., and significance values were calculated according to two-tailed t-tests with unequal variance.

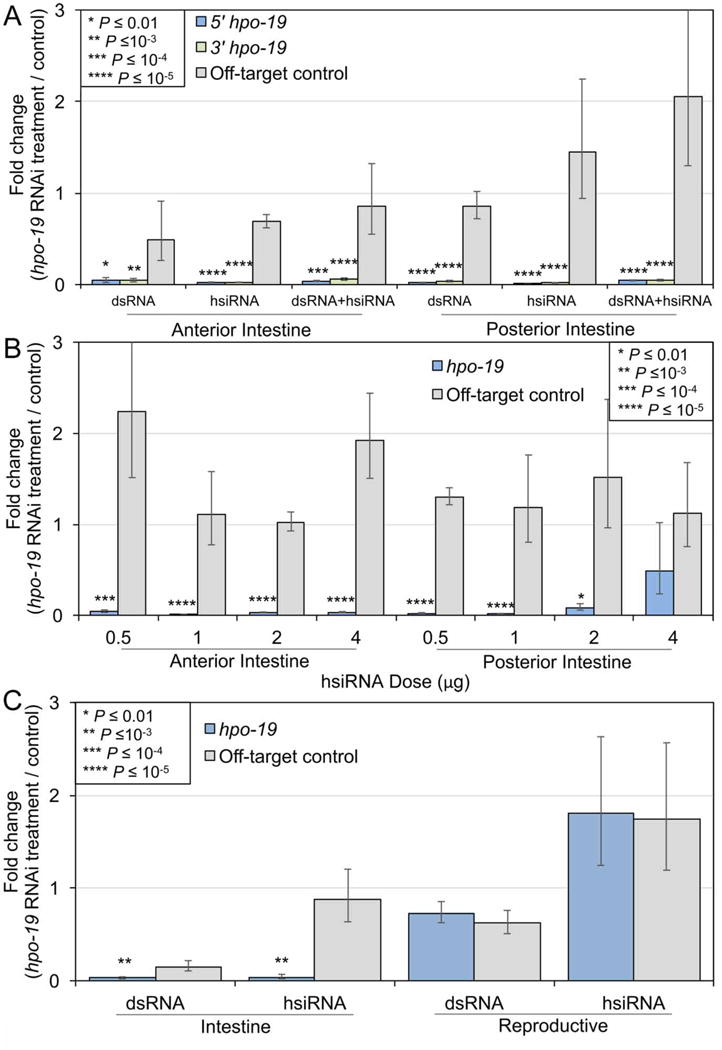

Fig. 4.

Real-time (RT) PCR experimentation to optimize double-stranded (ds)RNA delivery in the cannulated Ascaris suum experimental system. (A) The effect on hpo-19 knockdown as a result of utilizing different dsRNA preparations in the anterior and posterior A. suum intestine. (B) The effect on hpo-19 knockdown as a result of different heterogeneous small interfering dsRNA (hsiRNA) doses in the anterior and posterior A. suum intestine. (C) The effect on hpo-19 knockdown in the intestine and reproductive tissue as a result of dsRNA and hsiRNA delivery in the intrapseudocoelomic (IP) injection experimental design. Error bars represent S.D., and significance values were calculated according to two-tailed t-tests with unequal variance. RNAi, RNA interference.

The most efficacious target, hpo-19, was used to evaluate dose-dependence, dsRNA preparation (hsi-versus ds-RNA) and route of delivery on transcript knockdown. Differences in efficacy of transcript knockdown by dsRNA and hsiRNA delivered in culture have been reported for other parasitic nematodes, which could reflect differences in uptake across the cuticle, or apical intestinal membrane (Issa et al., 2005; Landmann et al., 2012). We found highly efficacious transcript knockdown in both anterior and posterior halves of intestine with dsRNA, hsiRNA or mixtures of both (Fig. 4A). Next, the amount of hsiRNA (hpo-19) delivered to each worm was varied from 4, 2, 1 and 0.5 μg, with no loss of transcript knockdown over this range (Fig. 4B) in the anterior intestine. Nevertheless, knockdown was not significant (P =0.4) with 4 μg of hsiRNA in the posterior intestine, which contrasts with the high efficacy in the posterior intestine shown previously for hpo-19 hsiRNA in Fig. 3. Variability in technical methods of dsRNA delivery may explain this variability in efficacy. Nevertheless, relatively low levels of perfused hsiRNA (0.5 μg) achieved transcript knockdown that is at least equivalent to higher treatment amounts (4 μg).

Previous research showed that IP injection of dsRNA caused transcript knockdown in adult A. suum tissues (including intestinal/hypodermis tissue), but intestine-specific effects were not delineated (McCoy et al., 2015). We performed IP treatments with otherwise intact worms (intact head and tail) and observed significant knockdown of target transcripts from the middle region of the intestine (associated with reproductive tissue) using either dsRNA or hsiRNA (hpo-19, 4 μg; Fig. 4C), thus confirming IP dsRNA delivery as an effective method to knockdown intestinal transcripts. In contrast, for reasons that are unclear, the associated reproductive tissue showed no significant knockdown of target transcripts.

3.2. Quantifying on- and off-target knockdown effects via genome-wide transcriptional RNAi response

The preceding experiments examined knockdown of specific intestinal transcripts, however off-target changes in transcript abundances can be extensive (Barik, 2006; Nunes et al., 2013). Consequently, quantifying transcript changes at the transcriptomic level resulting from dsRNA/hsiRNA treatments in the A. suum intestine will aid in interpretation of dsRNA-based experimental results. For this purpose, we conducted RNA-Seq analysis on intestinal RNA after hsiRNA treatment (using hpo-19 and ceh-20, the two most effective genes in our RT-PCR experiments), using 1.0 μg of hsiRNA, an intermediate amount with highly efficacious knockdown in both the anterior and posterior intestine (Fig. 4B). To isolate the hsiRNA treatment effects, we first quantified (and later controlled for) the combined experimental method effects of decapitation, cannulation, diluent perfusion and 24 h culture (24 h treatment control worms) on the global transcriptional profile by comparing time 0 h decapitated worms and the 24 h treatment control worms.

Compared with time 0 h decapitated worms, the 24 h treatment control worms had significant upregulation (159 genes) and downregulation (79 genes) of expression in both the anterior and posterior halves of the intestine (1.3% of all genes; Fig. 2, Table 2, Supplementary Table S3), including numerous changes in common between the two regions. Among these genes, GO enrichment (Table 2) identified 14 GO terms enriched, including terms related to nuclease activity and coenzyme activity among upregulated genes, and terms related to DNA replication, ATP binding and exopeptidase activity among downregulated genes. A STRING (Szklarczyk et al., 2015) protein network analysis, based on C. elegans orthologs of the A. suum proteins encoded by the differentially expressed transcripts (protein-protein networks based on orthologs have been used for various parasitic nematode species (Taylor et al., 2011)) identified a highly interconnected network (P = 7×10−8 for enrichment of connectivity) centered on the ubiquitin gene ubq-1, suggesting that strong differential regulation of genes involved in this network was initiated by the general experimental set-up (Supplementary Fig. S2). Nevertheless, the number of gene transcripts affected here were modest compared with in vitro culture effects on the adult Brugia malayi transcriptome, in which transcript expression was changed for 1,020 genes (Ballesteros et al., 2016). Based on reciprocal best matches of encoded proteins, 44 and 27 A. suum gene transcripts, up- or downregulated (inclusive of anterior, posterior, and both halves of the intestine), respectively, were found in common with the B. malayi data set, suggesting that culture effects may account for some of the transcript changes observed in A. suum intestinal cells. Alternatively, transcript changes may result from decapitation below the esophagus/nerve ring, as C. elegans intestinal gene expression is regulated by neuroendocrine input (Srinivasan, 2015), or from cannulation/perfusion effects, for which there is no available relevant information.

Table 2.

Gene Ontology (GO) terms significantly enriched among gene sets consistently upregulated and downregulated by the Ascaris suum cannulation treatment procedure.

| Direction | Category | Term ID | Term Description | P value | Count | Term size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | Molecular Function | GO:0004527 | exonuclease activity | 1.7E-05 | 4 | 15 |

| Biological Process | GO:0006732 | coenzyme metabolic process | 2.2E-03 | 4 | 54 | |

| Biological Process | GO:0051186 | cofactor metabolic process | 2.5E-03 | 4 | 56 | |

| Molecular Function | GO:0004518 | nuclease activity | 3.0E-03 | 4 | 55 | |

| Biological Process | GO:0044283 | small molecule biosynthetic process | 3.5E-03 | 4 | 61 | |

| Biological Process | GO:0009108 | coenzyme biosynthetic process | 7.4E-03 | 3 | 39 | |

| Biological Process | GO:0051188 | cofactor biosynthetic process | 8.5E-03 | 3 | 41 | |

| Downregulated | Biological Process | GO:0006270 | DNA replication initiation | 1.8E-04 | 3 | 14 |

| Biological Process | GO:0006261 | DNA-dependent DNA replication | 3.4E-04 | 3 | 17 | |

| Molecular Function | GO:0008238 | exopeptidase activity | 1.4E-03 | 3 | 35 | |

| Molecular Function | GO:0005524 | ATP binding | 3.2E-03 | 13 | 891 | |

| Molecular Function | GO:0032559 | adenyl ribonucleotide binding | 3.2E-03 | 13 | 893 | |

| Molecular Function | GO:0030554 | adenyl nucleotide binding | 3.3E-03 | 13 | 894 | |

| Molecular Function | GO:0003677 | DNA binding | 4.3E-03 | 9 | 505 |

Next, global transcript changes induced in intestinal cells by each hsiRNA treatment were determined independently (controlling for cannulation treatment effects using DESeq; see Section 2), and then differential expression specific to or shared between hsiRNA treatments were distinguished for transcripts in anterior, posterior, or both intestinal regions (Fig. 2). Transcript abundance effects ascribable to either hsiRNA treatment were far more numerous than those that were in common between the two different hsiRNA treatments, with the target genes being the most significantly downregulated genes in their respective treatments (hpo-19, P = 4×10−48, ceh-20, P = 5×10−10; Supplementary Table S3). Only eight and four genes were up- and downregulated by both hsiRNA treatments (respectively; 0.07% of all genes) in both the anterior and posterior intestine (Fig. 2E, F). An additional 52 genes were differentially regulated only in the anterior or posterior intestine (derived from Supplementary Table S3).

Those changes identified in common, up or down, could reflect general physiological responses of intestinal cell exposure to dsRNA, such as stress or innate immune responses, as suggested for insect cells (Kingsolver and Hardy, 2012; Nunes et al., 2013). However, of the eight genes upregulated by both hsiRNA treatments in both the anterior and posterior intestine, there was no evidence of immune response or stress gene responses. One upregulated gene (GS_19094) was associated with RNA processing (“RNA-binding protein 5/10”, K13094, related to intron splicing), and the seven other genes have a variety of functions with no obvious theme, including a dopamine receptor (GS_19561), a sulfate permease (GS_00322), and an aconitate hydratase (GS_09209), while the most significantly upregulated gene in the set (GS_11054) has no functional annotation assigned. The four genes downregulated by hsiRNA treatments in both the anterior and posterior intestine included: (i) GS_04133, which has no functional annotation, but was previously predicted to be a target for endogenous miRNA silencing in the A. suum intestine (Gao et al., 2016); (ii) GS_13545, an RNA polymerase II for which the C. elegans ortholog (rpb-12) was used as a non-variable control gene in other studies (Ventura et al., 2009; Darom et al., 2010); (iii) GS_21168, a C-type lectin, and (iv) GS_05428, which has no informative functional information.

We explored explanations for off-target effects that might be contained in our dataset. For example, a search of 20 bp sequences of the dsRNA sequences used to generate hsiRNA identified no significant homology to off-target genes that may explain downregulation of any transcripts. Alternatively, dsRNA treatments are likely to compete for RNAi metabolic machinery with microRNAs (miRNAs) (e.g. RISC; Khan et al., 2009), which could stabilize target transcripts that are normally downregulated by intestinal miRNAs. We previously identified predicted intestinal miRNA target transcripts in A. suum intestinal cells (Gao et al., 2016), but found no general upregulation of these intestinal transcripts. Thus, we have no ready explanation for the effects on other cellular transcripts documented here.

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that the adult A. suum intestinal perfusion method supports controlled, effective delivery of dsRNA treatments to the apical intestinal membrane, which translated into specific transcript knockdown. No other model system currently exists to achieve controlled delivery of this kind in any other nematode species, which is facilitated by the large size of A. suum. Existing pan-Nematoda intestinal gene/protein databases (Wang et al., 2015) can be used to interpret and extend findings of basic intestinal cell functions to other parasitic nematode species.

Although feeding of dsRNA has been accomplished for multiple parasitic nematode species (Lendner et al., 2008; Lilley et al., 2012; Selkirk et al., 2012; Antonino de Souza Júnior et al., 2014), the amount and timing of dsRNA ingestion is difficult to measure or control, and unpredictable effects of in vitro culture on delivery (Lendner et al., 2008) seriously limit some applications of this approach. Our novel approach of dsRNA delivery by intestinal perfusion is an effective solution to obstacles of dsRNA feeding, and relevant to potential therapeutic applications in which dsRNA could be used directly to treat helminth infections, via the apical intestinal membrane. We observed no systematic differences between use of dsRNA and the more complex (but sometimes more efficacious (Issa et al., 2005)) hsiRNA in achieving intestinal transcript knockdown when delivered by intestinal perfusion, and the A. suum model can support assessment of numerous dsRNA designs and treatments to maximize anthelmintic effects of dsRNA. The relative efficacy of the simpler constructs should be advantageous for the development of anthelmintic dsRNA delivery systems.

The results also reinforce the need to seek optimization of dsRNA treatments relative to both biological and anthelmintic studies. Although two dsRNA constructs (hpo-19 and ceh-20) induced rapid and high-level transcript knockdown within 24 h, variation in efficacy was observed among the dsRNA constructs for different genes. Variation of this kind is not unusual (Vert et al., 2006), and may be explained by the restricted 24 h time frame or off-target dsRNA regulation (as suggested for sre-12), as examples. We determined that relatively low quantities of dsRNA (0.5 μg) per worm were efficacious, but it remains to be determined if lower amounts would lead to more rapid knockdown, or effective knockdown of the recalcitrant transcripts. These points serve to emphasize that consensus optimal conditions need to be defined to achieve full use of this model, which can now be approached based on the progress reported. Nevertheless, it is recognized that approaches distinct from dsRNA knockdown may be required to investigate functions of different intestinal genes and proteins.

RNA-Seq analysis of global intestinal transcript effects resulting from dsRNA/hsiRNA perfusion added another dimension to the overall model. Differential transcript regulation was resolved relative to the experimental method, common responses to different dsRNA treatments (as seen in other systems (Barik, 2006; Nunes et al., 2013)), and responses restricted to individual hsiRNA sequences. Overall, off-target effects in the A. suum intestine are relatively modest, particularly in relation to effects that can be ascribed to both treatments and both regions of the A. suum intestine. Although most of the off-target effects are low in magnitude and unlikely to interfere with interpretation of specific knockdown effects, the results also show that use of multiple lines of information will enhance confidence in ascribing functions to transcripts (or encoded proteins) for which dsRNA knockdown is achieved. Use of a second non-overlapping dsRNA for target genes may help to confirm targeting in future research (Ulrich et al., 2015).

Collectively, the modest global transcriptomic responses of A. suum intestinal cells to intestinal-perfusion of dsRNA treatments are comparable with, or less than, other experimental systems (Nunes et al., 2013; Ballesteros et al., 2016), with high efficacy for target transcripts. As development of the A. suum model progresses, advances in experimental methods to manipulate intestinal cells should accelerate elucidation of intestinal cell functions with relevance to new anthelmintic approaches, and may extend to applications in other nematode tissues. The ability to introduce labels for metabolic and cellular processes via the lumen of the adult A. suum intestine and then isolate intact intestine for analysis, conduct many conventional cell/biochemical assays on isolated intestinal tissue/lysates, and conduct standard histochemical/ultrastructural analysis will enable assessment of fairly wide range of phenotypic effects that can be induced by targeted dsRNA knockdown experiments. Given the current state of technological development with this model, the most tractable applications of the method will likely involve investigation of specific hypothesis in a treatment-assessment manner, rather than broad scale screening for induced phenotypes by RNAi, or longitudinal studies of functions. Nevertheless, other larval stages (liver, L3; lung, L4; and intestinal, L4) might offer screening capabilities that relate to intestinal cell functions and have been used in treatment-infection studies during the life cycle (Islam et al., 2005).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. S1. Real-time (RT)-PCR results from performing double-stranded (ds)RNA+ heterogeneous small interfering dsRNA (hsiRNA) treatment in the anterior and posterior Ascaris suum intestine, against the target genes (A) ddx-23, (B) drr-1 and (C) sre-12. Error bars represent S.D., and significance values were calculated according to two-tailed t-tests with unequal variance.

Supplementary Fig. S2. STRING protein networks for Caenorhabditis elegans orthologs of genes differentially expressed by cannulation treatment but not by RNA interference (RNAi) treatment.

Highlights.

Direct delivery of treatments to Ascaris suum intestinal lumen and apical membrane

Derivation of optimal methods for direct delivery of double-stranded (ds)RNA to intestinal cells

Global intestinal transcriptomic effects of the delivery method and dsRNA treatments

Modest intestinal transcriptomic responses to the method and dsRNA treatments

Transcriptomic responses to the method suggest convergence on ubiquitin pathways

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH, USA) Grant #GM097435 to MM and subcontract #WU-17-182 to DPJ. We thank Susan Smart for excellent technical support on experiments conducted with Ascaris suum.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Note: Supplementary data associated with this article

References

- Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonino de Souza Júnior JD, Ramos Coelho R, Tristan Lourenço I, da Rocha Fragoso R, Barbosa Viana AA, Lima Pepino de Macedo L, Mattar da Silva MC, Gomes Carneiro RM, Engler G, de Almeida-Engler J, Grossi-de-Sa MF. Knocking-Down Meloidogyne incognita Proteases by Plant-Delivered dsRNA Has Negative Pleiotropic Effect on Nematode Vigor. PLoS One. 2014;8:e85364. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros C, Tritten L, O’Neill M, Burkman E, Zaky WI, Xia J, Moorhead A, Williams SA, Geary TG. The Effect of In Vitro Cultivation on the Transcriptome of Adult Brugia malayi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barik S. RNAi in moderation. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:796–797. doi: 10.1038/nbt0706-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethony JM, Loukas A, Hotez PJ, Knox DP. Vaccines against blood-feeding nematodes of humans and livestock. Parasitology. 2006;133(Suppl):S63–S79. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006001818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Xu MJ, Nisbet AJ, Huang CQ, Lin RQ, Yuan ZG, Song HQ, Zhu XQ. Ascaris suum: RNAi mediated silencing of enolase gene expression in infective larvae. Exp Parasitol. 2011;127:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium, T.G.O. Gene Ontology Annotations and Resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D530–D535. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darom A, Bening-Abu-Shach U, Broday L. RNF-121 Is an Endoplasmic Reticulum-Membrane E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Involved in the Regulation of β-Integrin. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1788–1798. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-09-0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon S, Gentleman R. Using GOstats to test gene lists for GO term association. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:257–258. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Tyagi R, Magrini V, Ly A, Jasmer DP, Mitreva M. Compartmentalization of functions and predicted miRNA regulation among contiguous regions of the Nematode Intestine. RNA Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1166333. E-pub Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadwiger G, Dour S, Arur S, Fox P, Nonet ML. A Monoclonal Antibody Toolkit for C. elegans. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TW, Baran J, Bieri T, Cabunoc A, Chan J, Chen WJ, Davis P, Done J, Grove C, Howe K, Kishore R, Lee R, Li Y, Muller HM, Nakamura C, Ozersky P, Paulini M, Raciti D, Schindelman G, Tuli MA, Van Auken K, Wang D, Wang X, Williams G, Wong JD, Yook K, Schedl T, Hodgkin J, Berriman M, Kersey P, Spieth J, Stein L, Sternberg PW. WormBase 2014: new views of curated biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden-Dye L, Walker RJ. Anthelmintic drugs. WormBook; 2007. pp. 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Aroian RV. Bacterial pore-forming proteins as anthelmintics. Invert Neurosci. 2012;12:37–41. doi: 10.1007/s10158-012-0135-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MK, Miyoshi T, Yamada M, Tsuji N. Pyrophosphatase of the roundworm Ascaris suum plays an essential role in the worm’s molting and development. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1995–2004. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.1995-2004.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa Z, Grant WN, Stasiuk S, Shoemaker CB. Development of methods for RNA interference in the sheep gastrointestinal parasite, Trichostrongylus colubriformis. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:935–940. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AL, Linsley PS. Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off-target effects for target identification and therapeutic application. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:57–67. doi: 10.1038/nrd3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasmer D, Rosa B, Mitreva M. Peptidases compartmentalized to the Ascaris suum intestinal lumen and apical intestinal membrane. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;9:e3375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasmer DP, Yao C, Rehman A, Johnson S. Multiple lethal effects induced by a benzimidazole anthelmintic in the anterior intestine of the nematode Haemonchus contortus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;105:81–90. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jex AR, Liu S, Li B, Young ND, Hall RS, Li Y, Yang L, Zeng N, Xu X, Xiong Z, Chen F, Wu X, Zhang G, Fang X, Kang Y, Anderson GA, Harris TW, Campbell BE, Vlaminck J, Wang T, Cantacessi C, Schwarz EM, Ranganathan S, Geldhof P, Nejsum P, Sternberg PW, Yang H, Wang J, Wang J, Gasser RB. Ascaris suum draft genome. Nature. 2011;479:529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature10553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, McWilliam H, Maslen J, Mitchell A, Nuka G, Pesseat S, Quinn AF, Sangrador-Vegas A, Scheremetjew M, Yong SY, Lopez R, Hunter S. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AA, Betel D, Miller ML, Sander C, Leslie CS, Marks DS. Transfection of small RNAs globally perturbs gene regulation by endogenous microRNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:549–555. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsolver MB, Hardy RW. Making connections in insect innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18639–18640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216736109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvam VM, Liu P, Si Y. A comparison of statistical methods for detecting differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Am J Bot. 2012;99:248–256. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1100340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmann F, Foster JM, Slatko BE, Sullivan W. Efficient in vitro RNA interference and immunofluorescence-based phenotype analysis in a human parasitic nematode, Brugia malayi. Parasit Vect. 2012;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendner M, Doligalska M, Lucius R, Hartmann S. Attempts to establish RNA interference in the parasitic nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;161:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Khajuria C, Rangasamy M, Gandra P, Fitter M, Geng C, Woosely A, Hasler J, Schulenberg G, Worden S, McEwan R, Evans C, Siegfried B, Narva KE. Long dsRNA but not siRNA initiates RNAi in western corn rootworm larvae and adults. J Appl Entomol. 2015;139:432–445. [Google Scholar]

- Lilley CJ, Davies LJ, Urwin PE. RNA interference in plant parasitic nematodes: a summary of the current status. Parasitology. 2012;139:630–640. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011002071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy CJ, Warnock ND, Atkinson LE, Atcheson E, Martin RJ, Robertson AP, Maule AG, Marks NJ, Mousley A. RNA interference in adult Ascaris suum – an opportunity for the development of a functional genomics platform that supports organism-, tissue- and cell-based biology in a nematode parasite. Int J Parasitol. 2015;45:673–678. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty SN, Fischer PU, Townsend RR, Curtis KC, Weil GJ, Mitreva M. Systems biology studies of adult Paragonimus lung flukes facilitate the identification of immunodominant parasite antigens. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes FM, Aleixo AC, Barchuk AR, Bomtorin AD, Grozinger CM, Simoes ZL. Non-Target Effects of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)-Derived Double-Stranded RNA (dsRNA-GFP) Used in Honey Bee RNA Interference (RNAi) Assays. Insects. 2013;4:90–103. doi: 10.3390/insects4010090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa BA, Jasmer DP, Mitreva M. Genome-wide tissue-specific gene expression, co-expression and regulation of co-expressed genes in adult nematode Ascaris suum. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa BA, Townsend R, Jasmer DP, Mitreva M. Functional and phylogenetic characterization of proteins detected in various nematode intestinal compartments. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14:812–827. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.046227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protocols. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk ME, Huang SC, Knox DP, Britton C. The development of RNA interference (RNAi) in gastrointestinal nematodes. Parasitology. 2012;139:605–612. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011002332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S. Regulation of body fat in Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu Rev Physiol. 2015;77:161–178. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Roth A, Santos A, Tsafou KP, Kuhn M, Bork P, Jensen LJ, von Mering C. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CM, Fischer K, Abubucker S, Wang Z, Martin J, Jiang D, Magliano M, Rosso MN, Li BW, Fischer PU, Mitreva M. Targeting protein-protein interactions for parasite control. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich J, Dao VA, Majumdar U, Schmitt-Engel C, Schwirz J, Schultheis D, Ströhlein N, Troelenberg N, Grossmann D, Richter T, Dönitz J, Gerischer L, Leboulle G, Vilcinskas A, Stanke M, Bucher G. Large scale RNAi screen in Tribolium reveals novel target genes for pest control and the proteasome as prime target. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:674. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1880-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura N, Rea SL, Schiavi A, Torgovnick A, Testi R, Johnson TE. p53/CEP-1 Increases or Decreases Lifespan, Depending on Level of Mitochondrial Bioenergetic Stress. Aging Cell. 2009;8:380–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert JP, Foveau N, Lajaunie C, Vandenbrouck Y. An accurate and interpretable model for siRNA efficacy prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:520. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Rosa BA, Jasmer DP, Mitreva M. Pan-Nematoda Transcriptomic Elucidation of Essential Intestinal Functions and Therapeutic Targets With Broad Potential. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:1079–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JS, Reed A, Chen F, Stewart CN. Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:85–85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. S1. Real-time (RT)-PCR results from performing double-stranded (ds)RNA+ heterogeneous small interfering dsRNA (hsiRNA) treatment in the anterior and posterior Ascaris suum intestine, against the target genes (A) ddx-23, (B) drr-1 and (C) sre-12. Error bars represent S.D., and significance values were calculated according to two-tailed t-tests with unequal variance.

Supplementary Fig. S2. STRING protein networks for Caenorhabditis elegans orthologs of genes differentially expressed by cannulation treatment but not by RNA interference (RNAi) treatment.