Abstract

Reproductive coercion is behavior that interferes with a woman's autonomous reproductive decision-making. It may take the form of birth control sabotage, pregnancy coercion, or controlling the outcome of a pregnancy. Perpetrators may be partners, a partner's family, or the woman's family. This article reviews the literature on reproductive coercion in international settings. In this review of 10 research studies, findings are presented on prevalence and type of reproductive coercion, associated factors, specific tactics, relationship with intimate partner violence and domestic violence (in-laws particularly), and implications for women's reproductive health. Findings highlight reproductive coercion as a subset of intimate partner violence that is poorly understood, especially in international settings. More research is needed on protective factors, how interventions can capitalize on protective factors, and the strategies women use to resist reproductive coercion. Policy implications and recommendations are discussed with particular attention to issues related to diverse social and cultural environments.

Keywords: Reproductive coercion, unintended pregnancy, intimate partner violence

Introduction

Reproductive coercion is behavior that interferes with a woman's autonomy in reproductive decisions (Miller et al. 2010; Moore, Frohwirth, and Miller 2010). This may take the form of birth control sabotage (such as removing a condom, damaging a condom, removing a contraceptive patch, or throwing away oral contraceptives), pregnancy coercion, or controlling the outcome of a pregnancy (such as pressure to continue a pregnancy or pressure to terminate a pregnancy) (Miller et al. 2010; Moore et al. 2010). When reproductive coercion has been studied in the United States, perpetrators are almost exclusively intimate partners (Borrero et al. 2015; Clark et al. 2014; Hathaway et al. 2005; McCauley et al. 2015; McCauley, Dick, et al. 2014; Miller et al. 2007, 2010, 2014; Moore et al. 2010; Nikolajski et al. 2015; Sutherland, Fantasia, and Fontenot 2015). In international settings and studies of immigrant women, perpetrators have been found to also include family members of the woman or of her partner (Char, Saavala, and Kulmala 2010; Clark et al. 2008; Gupta et al. 2012; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014; Puri et al. 2011; Raj et al. 2011). Women in in different countries, due to different social and cultural norms and legal rights, may experience reproductive coercion in disparate ways from women in the United States and from each other. These differences may have different implications for clinicians, researchers and policy makers. Hence, this paper focuses exclusively on literature on reproductive coercion in international settings.

Reproductive coercion was first defined in the literature in 2010 (Miller et al. 2010; Moore et al. 2010). This review examines literature from 5 years prior to this definition until 5 years hence (2005-2015), and highlights themes such as the impact of social and cultural norms surrounding involvement of in-laws and male partners in family planning decisions, a preference for male children, and attempts by women to resist coercion. The objectives of this article are to review the current state of knowledge about reproductive coercion and about the specific behaviors of reproductive coercion, when examined separately, in international settings, to address the questions:

What is known about reproductive coercion?

What strategies do women use to preserve their reproductive autonomy when experiencing reproductive coercion?

What interventions are effective to decrease reproductive coercion?

Methods

A research librarian assisted with literature searches, which were preformed in July 2015. The databases PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Embase were searched, including search terms “reproductive”, “coercion”, “sexual partners”, “pregnancy”, “contraception”, “birth control”, “reproductive behavior” and “sexual behavior”. Inclusion criteria were research studies of humans, English language, and the ten-year period surrounding the first mention of reproductive coercion in the literature (2005 to 2015) that covered reproductive coercion or any of its specific behaviors, and were set in locations outside the United States. Abstracts and titles were reviewed by both authors for this inclusion criteria, as well as exclusion criteria: only examining sexual coercion, IPV, or coercion by the government (e.g., forced sterilization). Articles that were potentially relevant were reviewed in full-text for inclusion and exclusion criteria by both authors. Following database searches, a hand search was conducted on the reference lists of all relevant articles.

The Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) (Stroup et al. 2000) and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Liberati et al. 2009) protocols guided the review. The authors extracted data from each included article on the topics of reproductive coercion (including birth control sabotage, pregnancy coercion, and abortion coercion), the intersection with IPV, the intersection with unintended pregnancy, resistance strategies, and supportive interventions, when such data were present. The authors then compiled the data chronologically to facilitate analysis of this emerging area of research.

Quality assessments of each research study were conducted using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for cross-sectional studies (Vandenbroucke et al. 2007), the Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nurses (JOGNN) Qualitative Research assessment tool for qualitative studies (Cesario, Morin, and Santa-Donato 2002), and the Journal of Mixed Methods Research review criteria for mixed methods studies (Journal of Mixed Methods Research n.d.). The STROBE checklist and Journal of Mixed Methods tool do not include scoring systems. These tools were adapted for purposes of this review, and a scoring system comparable to the JOGNN instrument was created, to enable comparison of studies.

Results

Description of Studies

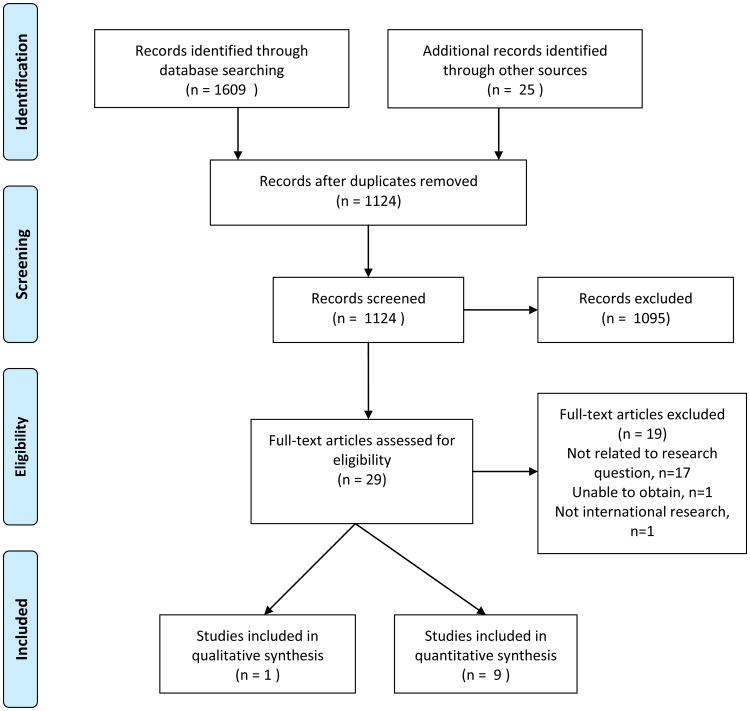

Search results are summarized and displayed in Figure 1. Initial searches of electronic databases yielded 1,569 citations, and the hand search of reference lists yielded an additional 25, for a total of 1,594 citations. After removing duplicates, screening titles and abstracts, and excluding articles based on exclusion criteria, 10 articles remained to be reviewed.

Figure 1. Results of Search Strategies on Reproductive Coercion in International Settings.

The research reviewed included 1 qualitative study and 9 quantitative studies, of which 1 was mixed-methods and 8 were cross-sectional studies. Only 2 of these studies specifically aimed to examine the phenomenon of reproductive coercion (Gupta et al. 2012; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014); the remaining studies reported on component behaviors of reproductive coercion, incidental to the specific aims of the study. Of the 10 studies, 2 contained findings regarding the general phenomenon of reproductive coercion (Gupta et al. 2012; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014), and all 10 contained findings about a specific behavior of reproductive coercion. Specifically, 4 contained findings about pregnancy coercion (Char et al. 2010; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014; Raj et al. 2011; Salam, Alim, and Noguchi 2006), 2 contained findings on birth control sabotage (Clark et al. 2008; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014), and 2 contained findings on abortion coercion (Raj et al. 2011; Wu, Guo, and Qu 2005). Additionally, 4 studies contained findings related to the intersection of IPV and reproductive coercion (Clark et al. 2008; Gupta et al. 2012; Romito et al. 2009; Zakar et al. 2012), 4 contained findings about other factors that are associated with reproductive coercion (Clark et al. 2008; Gupta et al. 2012; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014; Okunlola et al. 2006), 1 contained findings related to strategies women use to resist reproductive coercion (McCauley, Falb, et al., 2014) and no studies contained findings on interventions for reproductive coercion or unintended pregnancy. International research on reproductive coercion covered a broad range of geographical areas. Studies were set in Pakistan (Zakar et al., 2012), China (Wu et al. 2005), Nigeria (Okunlola et al. 2006), Bangladesh (Salam et al. 2006), Jordan (Clark et al. 2008), Italy (Romito et al. 2009), India (Char et al. 2010; Raj et al. 2011), and Cote d'Ivoire (Gupta et al. 2012; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014). Results are summarized below, grouped according to the findings, and are reported in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Table 1. Sample, Quality, and Findings About Types of Reproductive Coercion.

| First Author (year) Methodology | Setting and Sample | Ethnic/Religious Breakdown of Sample (if noted) | Perpetrator | Findings | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive Coercion - General | |||||

|

Gupta (2012) Cross-sectional survey |

Rural Cote d'Ivoire 981 Ivorian women aged ≥18 years witha male partner and a current income source |

Religion (Christian, Muslim, Traditional) plus 7 African ethnicities | In-laws | 6% reported lifetime reproductive coercion by in-laws | QI |

|

McCauley (2014) Cross-sectional survey |

Rural Cote d'Ivoire 953 Ivorian women aged ≥18 years with a male partner |

Religion (Christian, Muslim, Traditional) plus 5 African ethnicities | In-laws | 5.5% reported lifetime reproductive coercion by in-laws | QI |

| Male Partner | 18.5% reported lifetime reproductive coercion by a male partner | ||||

| Pregnancy Coercion | |||||

|

Salam (2006) Cross-sectional survey |

4 urban slums in Bangladesh 496 married women of reproductive age |

Not reported | Male partner | 10% of women reporting IPV and 10.4% of women not reporting IPV reported husbands disagreeing with them about the use of contraception | QI |

|

Clark (2008) Cross-sectional survey |

Family planning clinics in Jordan 353 literate, ever-married women aged 15-49 |

Religion (Muslim, Christian) | In-laws | 13% reported that someone had tried to stop them from using contraception. The “others” in this category: mothers-in-law (36 percent) mothers (27 percent) sisters-in-law (11 percent) Tactics of interference with contraception: Telling her they disapproved of contraception 90% |

QI |

| Male partner | 11% reported their husband ever refused to use a contraceptive method or tried to stop them from using one Tactics of interference with contraception: Telling the respondent that they disapproved of contraception 89% |

||||

|

Char (2010) Qualitative |

Rural India 60 families (180 family members) from 12 villages |

Religion (all Hindu) | In-laws | Majority of mothers-in-law felt they should decide about timing of daughters-in-law's use of female sterilization; wanted them to delay sterilization until the mother-in-law's desired number of sons were produced. | QII |

| Male partner | 11 of the 60 husbands reported they excluded their wives from contraceptive decision-making | QII | |||

|

Raj (2011) Mixed Methods |

Mumbai, India Qualitative portion: 32 mothers of infants presenting for infant care at urban health centers, who reported IPV in prior year Quantitative portion: 1038 mothers, aged 15–35 years, seeking infant immunization services at three large health centers located in slum areas |

Religion (Muslim, Hindu) | In-laws | Women reported in-laws pressuring them to get pregnant and making decisions regarding timing of conception One woman reported in-law pressure to give a female child to an infertile sister-in-law, against the woman's wishes. |

QI |

|

McCauley (2014) Cross-sectional survey |

Rural Cote d'Ivoire 953 Ivorian women aged ≥18 years with a male partner |

Religion (Christian, Muslim, Traditional) plus 5 African ethnicities | In-laws | Reported pregnancy pressure tactics by in-laws included: Telling husband to leave if she did not get pregnant 3.8% Telling husband to have a baby with someone else if she did not get pregnant 3.8% Humiliating her if she did not get pregnant 2.6% Trying to force or pressure her to get pregnant 2.3% Telling her not to use any birth control (e.g. the pill or shot) 2.0% Telling husband to prevent her from using any birth control 1.4% Telling husband to hurt her physically because she did not get pregnant 0.9% Not allowing her in the house if she did not become pregnant 0.4% Not allowing her to eat because she did not become pregnant 0.2% |

QI |

| Male partner | Reported pregnancy pressure tactics by male partner included: Telling her not to use any birth control 9.1% Telling her he would have a baby with someone else if she did not get pregnant 5.6% Telling her he would leave her if she did not get pregnant 5.2% Making her have sex without a condom 5.0% Trying to force or pressure her to become pregnant 4.5% |

QI | |||

| Birth Control Sabotage | |||||

|

Clark (2008) Cross-sectional survey |

Family planning clinics in Jordan 353 literate, ever-married women aged 15-49 |

Religion (Muslim, Christian) | In-laws | Tactics of interference with contraception, mentioned infrequently: Taking or destroying contraception |

QI |

| Male partner | Tactics of interference with contraception, mentioned infrequently: Taking or destroying contraception |

||||

| Both | 20% reported their husband or someone else had interfered with their attempts to avert pregnancy | ||||

|

McCauley (2014) Cross-sectional survey |

Rural Cote d'Ivoire 953 Ivorian women aged ≥18 years with a male partner |

Religion (Christian, Muslim, Traditional) plus 5 African ethnicities | Male partner | Tactics of birth control sabotage reported by women: Taking off a condom during sex 1.9% Taking birth control (e.g. pills) away from her so that she would get pregnant 1.7% Putting holes in a condom so she would get pregnant 0.5% |

QI |

| Abortion Pressure | |||||

|

Wu (2005) Cross-sectional survey |

Hospitals that perform abortions in Northern China 1215 women requesting pregnancy termination who resided in the local city for at least 1 year |

Not reported | Male partner | 2.1% of women said they were being forced to have an abortion by their intimate partners | QII |

|

Raj (2011) Mixed Methods |

Mumbai, India Qualitative portion: 32 mothers of infants presenting for infant care at urban health centers, who reported IPV in prior year Quantitative portion: 1038 mothers, aged 15–35 years, seeking infant immunization services at three large health centers located in slum areas |

Religion (Muslim, Hindu) | In-laws | In qualitative interviews women reported in-laws making decisions regarding abortion In quantitative arm 1% of women reported in-laws forcing them to have abortions |

QI |

| Strategies of Resistance | |||||

|

McCauley (2014) Cross-sectional survey |

Rural Cote d'Ivoire 953 Ivorian women aged ≥18 years with a male partner |

Religion (Christian, Muslim, Traditional) plus 5 African ethnicities | Male partner | 3% reported hiding birth control from partner because she thought he would be upset with her for using it | QI |

| Clinical Interventions | |||||

| No studies had findings in this area | |||||

NOTE: SES = socioeconomic status, IPV = intimate partner violence, RC = reproductive coercion, AOR = adjusted odds ratio, ARR = adjusted risk ratio

Quality ratings for cross-sectional and mixed-methods studies are as follows (Cesario et al., 2002):

QI: Total score of 22.5–30 indicates that 75% to 100% of the total criteria were met.

QII: Total score of 15–22.4 indicates that 50% to 74% of the total criteria were met.

QIII: Total score of less than 15 indicates that less than 50% of the total criteria were met.

Table 2. Findings on the Intersection of Reproductive Coercion and Intimate Partner or In-Law Violence.

| First Author (year) Methodology | Setting and Sample | Ethnic/Religious Breakdown of Sample (if noted) | Perpetrator | Findings on Intersection with IPV or In-Law Violence | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Salam (2006) Cross-sectional survey |

4 urban slums in Bangladesh 496 married women of reproductive age |

Not reported | Male partner | 10% of women reporting IPV and 10.4% of women not reporting IPV reported husbands disagreeing with them about the use of contraception (not a significant difference, and no association was found between IPV and disagreement with contraception) | QI |

|

Clark (2008) Cross-sectional survey |

Family planning clinics in Jordan 353 literate, ever-married women aged 15-49 |

Religion (Muslim, Christian) | Male partner | Women who reported ever experiencing IPV were 2.4 times more likely than women who did not experience IPV to also report interference with attempts to control fertility (p-value 0.00) Women who reported ever experiencing sexual violence by their husband were 3.1 times more likely than women who did not report sexual violence to also report interference (p-value 0.00) Women who reported experiencing controlling behaviors by their husbands were 1.4 times more likely than women who did not experience controlling behavior to also report interference (p-value 0.00) |

QI |

|

Romito (2009) Unmatched, case-control study |

Trieste, Italy Cases: all (445) consecutive abortions occurring during the 16 month study period Unmatched controls:All (438) consecutive live births occurring during an overlapping 5 month study period in the same hospital |

Nationality - Italian vs Non-Italian | Male partner | For women who had abortions: 2% of those without partner violence 7% of those with psychological violence 13% of those with physical or sexual violence reported that the conception had occurred because “the partner wanted her to become pregnant” (p = .002) 4.5% of those without partner violence 3.6% of those with psychological violence 21.7% of those with physical or sexual violence reported they decided to have an abortion because “the partner wanted a child, but they did not” (p = .002) |

QI |

|

Gupta (2012) Cross-sectional survey |

Rural Cote d'Ivoire 981 Ivorian women aged ≥18 years with a male partner and a current income source |

Religion (Christian, Muslim, Traditional) plus 7 African ethnicities | In-laws | Among women who reported maltreatment by in-laws: 15.9% reported reproductive coercion Among women who did not report maltreatment by in-laws: 2.8% reported reproductive coercion (P < 0.0001) Among women who reported physical violence by in-laws: 16.3% reported reproductive coercion Among women who did not report physical violence by in-laws: 5.9% reported reproductive coercion (P = 0.006). Unadjusted analyses: women who reported abuse by in-laws were over six times more likely to report reproductive coercion (OR 6.5; 95% CI 3.8–11.2; P < 0.0001) Adjusted, multivariable logistic regression analysis: women who reported abuse by in-laws were also over six times more likely to report reproductive coercion (AOR 6.9; 95% CI 3.9–12.2; P < 0.0001) |

QI |

|

Zakar (2012) Cross-sectional survey |

Tertiary-care hospitals in 2 cities in Pakistan 373 ever-married women of reproductive age (15–49 years) |

Not reported | Male partner | Women who experienced severe physical violence were more likely to report husband was not cooperative in the use of contraceptives (AOR 3.31; 95% CI 1.93–5.68 - p value <.0001) Women who experienced severe psychological violence were more likely to report husband was not cooperative in the use of contraceptives (AOR 1.72 (1.03-2.78) p value <0.05) Women who experienced sexual violence were more likely to report husband was not cooperative in the use of contraceptives (AOR 1.54 (0.97-2.46)) |

QI |

|

McCauley (2014) Cross-sectional survey |

Rural Cote d'Ivoire 953 Ivorian women aged ≥18 years with a male partner |

Religion (Christian, Muslim, Traditional) plus 5 African ethnicities | In-laws |

PTSD: 25.0% of the women who experienced reproductive coercion by in-laws reported past-week symptoms of PTSD (P < 0.05) 18.0% of the women who experienced in-law abuse reported past-week symptoms of PTSD (P < 0.05) Women who experienced reproductive coercion by in-laws were 2.3 times more likely to experience past-week symptoms of PTSD than women without exposure to coercion (95% CI, 1.2–4.4; P < 0.05) controlling for abuse by in-laws Women who experienced abuse by in-laws were 1.7 times more likely to experience past-week symptoms of PTSD thank women without exposure to abuse (95% CI, 1.2–2.6; P < 0.05) controlling for reproductive coercion Statistical models that assessed exposure to abuse by in-laws and reproductive coercion collectively found no significant association with past-week symptoms of PTSD |

QI |

| Male partner |

PTSD: 22.2% of women who reported reproductive coercion by a male partner reported past-week symptoms of PTSD (P < 0.001) Women who experienced reproductive coercion by a male partner were 2.6 times more likely than those who did not experience reproductive coercion to report past-week symptoms of PTSD (95% CI 1.7–4.0; P < 0.001), controlling for IPV Women who experienced IPV were 1.9 times more likely than those who did not experience IPV to report past-week symptoms of PTSD (95% CI, 1.2–3.0; P < 0.05), controlling for reproductive coercion Statistical models that assessed exposure to abuse and reproductive coercion collectively found reproductive coercion by male partner (OR 2.3; 95% CI, 1.4–3.9) and IPV (OR 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1–2.7) were significantly associated with past-week symptoms of PTSD (P < 0.05) |

NOTE: SES = socioeconomic status, IPV = intimate partner violence, RC = reproductive coercion, AOR = adjusted odds ratio, ARR = adjusted risk ratio

Quality ratings for cross-sectional and mixed-methods studies are as follows (Cesario et al., 2002):

QI: Total score of 22.5–30 indicates that 75% to 100% of the total criteria were met.

QII: Total score of 15–22.4 indicates that 50% to 74% of the total criteria were met.

QIII: Total score of less than 15 indicates that less than 50% of the total criteria were met.

Table 3. Findings on Non-IPV Factors Associated with Reproductive Coercion.

| First Author (year) Methodology | Setting and Sample | Ethnic/Religious Breakdown of Sample (if noted) | Perpetrator | Findings | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Okunlola (2006) Retrospective chart review |

Southwest Nigeria 867 women who had an IUD inserted |

Religion (Muslim, Christian) | Male partner |

Age: Coercion by husband as a reason for IUD removal was more common in younger women (74.2% of women who discontinued IUD) when compared to older (25.8% of women who discontinued IUD); (p<0.001) Education: Coercion by husband as a reason for IUD removal was more common, but not significantly, in women with less education (primary and secondary) (46.7% of women who discontinued IUD) when compared to women with tertiary level education (33.3% of women who discontinued IUD) |

QIII |

|

Clark (2008) Cross-sectional survey |

Family planning clinics in Jordan 353 literate, ever-married women aged 15-49 |

Religion (Muslim, Christian) | Both |

Rural vs. urban: Women who reported experiencing interference with attempts to avoid pregnancy were more likely to attend a rural clinic (26%) compared with respondents who did not report interference (15%). (p=0.01) Attending an urban clinic was protective against interference (OR 0.37-0.41, p-value 0.00) in all statistical models. Household residence: Residing with in-laws (24%), as compared with residing with immediate family only (18%), was associated with an increased risk of experiencing interference (not significant). Residing with in-laws increased odds of interference in all statistical models, with strongest findings in the model that included physical violence (OR 1.97, p-value 0.04) and no significant association in the model that included sexual violence (OR 1.69, p-value 0.11) Consanguinity: Women who reported interference were more likely to be unrelated to husbands (22%) compared to women who were related (17%). (p-value 0.10). Consanguinity was significantly protective against interference in all statistical models (OR 0.45-0.58, p-value 0.01-0.08), with strongest findings in the sexual violence model (OR 0.45, p-value 0.01) Number of children: Having five or more children was somewhat protective from interference in the models that included sexual violence (OR 0.39, p-value 0.05) and physical violence models (OR 0.42, p-value 0.06 No significant association in the model that included controlling behaviors (OR 0.52, p-value 0.16) |

QI |

|

Gupta (2012) Cross-sectional survey |

Rural Cote d'Ivoire 981 Ivorian women aged ≥18 years with a male partner and a current income source |

Religion (Christian, Muslim, Traditional) plus 7 African ethnicities | In-laws |

Number of pregnancies: Women who had no (AOR 7.0 (2.2–22.0) 0.001) or 1-3 pregnancies (AOR 2.1 (1.1–3.9) 0.02) were significantly more likely to report experiencing reproductive coercion from in-laws Literacy: Significantly more women who were literate (9.5%) reported experiencing reproductive coercion from in-laws, compared to women who were illiterate (5.3%) (p-value 0.02) in unadjusted models only Ethnicity: Guere women were significantly more likely to report experiencing reproductive coercion from in-laws (AOR 2.0 (1.1–3.6) 0.02) Religion: Women who were of Traditional faith were significantly more likely to report experiencing reproductive coercion from in-laws (AOR 2.3 (1.3–4.1) 0.005) Non-significant findings: education, occupation, marital status, literacy in adjusted models. |

QI |

NOTE: SES = socioeconomic status, IPV = intimate partner violence, RC = reproductive coercion, AOR = adjusted odds ratio, ARR = adjusted risk ratio

Quality ratings for cross-sectional and mixed-methods studies are as follows (Cesario et al., 2002):

QI: Total score of 22.5–30 indicates that 75% to 100% of the total criteria were met.

QII: Total score of 15–22.4 indicates that 50% to 74% of the total criteria were met.

QIII: Total score of less than 15 indicates that less than 50% of the total criteria were met.

Measurement Instruments

In an American context, studies of reproductive coercion predominantly use or adapt a set of 10 questions to measure reproductive coercion that were originally created by Miller and colleagues (2010) based on earlier qualitative work (Miller et al. 2007). One other relevant instrument has recently been developed for measuring reproductive autonomy (Upadhyay et al. 2014). The Reproductive Autonomy Scale measures reproductive coercion as a subdomain of reproductive autonomy, in a 14-item instrument that includes 5 items specific to reproductive coercion. In this review of international research, only 2 studies used the Miller reproductive coercion items (Gupta et al. 2012; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014), one of which reported strong reliability, with a Cronbach's alpha score of 0.93 (Gupta et al. 2012). None used the scale developed by Upadhyay and colleagues (2014).

Reproductive Coercion – General

While studies conducted in the United States frequently address the phenomenon of reproductive coercion by explicitly measuring each of its domains (Borrero et al. 2015; Clark et al. 2014; Hathaway et al. 2005; Kazmerski et al. 2015; McCauley et al. 2015; McCauley, Dick, et al. 2014; Miller et al. 2007, 2010, 2014; Moore et al. 2010; Nikolajski et al. 2015; Sutherland et al. 2015), only 2 international studies studied reproductive coercion as a specific phenomenon (most contained findings on a specific behavior of reproductive coercion) (Gupta et al. 2012; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014). Both reported findings from the same parent study. The limited data from studies in this area demonstrate higher prevalence of male partner perpetration (18.5 percent) as compared to in-law perpetration (6 percent) (Gupta et al. 2012; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014).

Pregnancy Coercion

Seven studies reported findings on pregnancy coercion, which for this review is considered pressure to become pregnant or not to become pregnant (pressure related to abortion will be considered separately). The behavior of telling a partner not to use birth control was considered a component of pregnancy coercion.

Four quantitative studies reported findings on male partner-perpetrated pregnancy coercion or pressure. Disagreement over the use of contraception, or refusal to allow the use of contraception, was found to occur less frequently (9-11 percent prevalence) than expression of disapproval of contraception (89 percent) (Clark et al. 2008; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014; Salam et al. 2006). Disapproval of contraception is a broad description of behavior that may reflect concern about health risks, religious objection, as well as pregnancy coercion. McCauley and colleagues (2014) report on specific tactics of pregnancy coercion such as telling the woman not to use any birth control or that her would leave her or have a baby with someone else if she did not get pregnant, as well as forcing sex without a condom, all of which have relatively low prevalence of around 5 percent.

Two quantitative studies reported findings on relative-perpetrated pregnancy coercion. Perpetrators included mothers-in-law, mothers, and sisters-in-law, with the majority of coercion described being expression of disapproval of the use of contraception (Clark et al. 2008). Less commonly, tactics by in-laws included telling husbands to leave or have a baby with someone else if the women did not get pregnant, using humiliation, force, or encouraging husbands to use violence or denial of food and housing if the woman did not get pregnant (McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014).

Qualitative findings describe male partners not allowing women to make decisions about contraception, and mothers-in-law controlling decision-making about timing of conception, sterilization, and expressing pressure to produce male children (Char et al. 2010; Raj et al. 2011).

Birth Control Sabotage

Two studies reported findings relating to birth control sabotage, perpetrated by both male partners and relatives. Sabotage included broadly defined “interference”, and less frequently, stealing, destroying or withholding contraception, removing a condom during sex, and putting holes in condoms (Clark et al. 2008; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014).

Abortion Coercion

Two studies reported findings on abortion coercion, which for this analysis is considered pressure to control the outcome of a pregnancy by termination, or pressure not to terminate. Both studies with findings in this area report on pressure to terminate a pregnancy, with low prevalence of 1 to 2 percent and both male partner and in-law perpetrators described (Raj et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2005). These prevalence numbers are low, but may be underreported due to fear of being turned away from abortion services if coercion is reported, and/or social desirability.

Intersection with Intimate Partner or In-Law Violence

Consistent with the literature set in the United States, international literature closely examines the intersection between reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence (IPV), additionally including in-law-perpetrated violence in this examination. Six studies reported findings on this intersection. Multiple studies demonstrate a significant association between violence and reproductive coercion; women who had experienced IPV and controlling behavior had a higher odds of experiencing birth control sabotage or pregnancy coercion (Clark et al. 2008; Romito et al. 2009; Zakar et al. 2012). A similar association is found for in-law perpetrated violence; maltreatment and physical violence by in-laws was identified as a significant risk factor for reproductive coercion (Gupta et al. 2012). This intersection of IPV and reproductive coercion was strongly associated with the outcome of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014). One study contradicted these findings, with no significant association found between IPV and disagreement with husbands over the use of contraception (Salam et al. 2006). Findings in this area are summarized in Table 2.

Other Associated Factors

Three studies presented findings on factors in addition to IPV, which were associated with reproductive coercion or behaviors of reproductive coercion. Risk factors for experiencing the behaviors of reproductive coercion included young age, higher levels of literacy, residing with in-laws, lower parity (Clark et al. 2008; Gupta et al. 2012; Okunlola et al. 2006). Findings were conflicting about levels of education being a risk factor or being protective, but higher literacy was a risk factor for in-law-perpetrated reproductive coercion (Gupta et al. 2012; Okunlola et al. 2006). Protective factors against birth control sabotage by both male partners and in-laws included attending an urban clinic (likely a marker for living in an urban area), consanguinity, and higher parity (Clark et al. 2008). Ethnicity and religion were factors in findings from Cote d'Ivoire; women of the ethnic group Guere or of Traditional faith were significantly more likely to report experiencing reproductive coercion from in-laws (Gupta et al. 2012). Findings in this area are summarized in Table 3.

Resistance Strategies

One study addressed strategies women used to resist reproductive coercion, which was limited to a small number of women hiding contraception from their male partners (McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014).

Clinical Interventions

While American researchers are beginning to examine clinical interventions for reproductive coercion such as screening and informational safety cards (Burton and Carlyle 2015; Clark et al. 2014; Miller et al. 2011), no international literature presented findings on this topic.

Discussion

Quality of evidence

Overall, the quality of studies reviewed was high. The qualitative study was rated QI, the highest category of quality. Weaknesses were in the areas of procedural rigor (failing to use member checking to validate findings, not mentioning saturation in data collection), confirmability, and no discussion of ethical rigor, such as the process for informed consent. The findings were relevant to practice and could contribute to theory development.

Quantitative studies also rated very high, with the majority rated QI, the highest category of quality. Some weaknesses included that few studies defined potential confounders or effect modifiers, and some studies were weak on providing details of measurement instruments. Few studies discussed power analysis in the determination of sample size, or discussed efforts to address or minimize bias. Several studies did not discuss limitations or generalizability of the findings. All studies were limited in their generalizability. Almost all quantitative studies were cross-sectional, and thus were unable to draw conclusions about causality. Findings about coercive behavior in IUD removal decisions were limited by combining results on “husband coercion” and “husband discomfort” (Okunlola et al. 2006), which highlights the difficulty in measurement in analysis in this emerging area of research. Reliance on self-report allows the possibility of social desirability bias, and over- or under-reporting.

Analysis of Ethnocentrism

Race is not examined as a factor in any studies in this review, as most studies used homogenous samples. Some studies reported on religion and/or ethnicity of participants, but few reported on any findings specific to these groups, and only two reported on these factors in association with reproductive coercion (Gupta et al. 2012; McCauley, Falb, et al. 2014). Socioeconomic status is not examined as a factor in any studies. Examination of these factors as potential modifiers would be a strength of future research. No studies reported whether attrition or response rates were different by demographic group.

Since reproductive coercion is an inherently gendered phenomenon, no analysis of androcentricity is discussed. However, it is noteworthy that most studies focused exclusively on female participants, with the exception of one that included males as part of a triad that included husbands, wives, and mother-in-laws (Char et al., 2010). No studies examined women of sexual minority status. Studies in the United States have suggested higher risk of reproductive coercion among women of sexual minority status (women who have sex with both women and men) (McCauley et al. 2015). Future research in this area would be strengthened by including men, and examining sexual minority status as a risk factor.

Summary of Evidence

The evidence reviewed in this article and the chronological display of findings (Tables 1-4) describes an emerging field of research of enormous importance to global women's healthcare that is poorly understood, but growing in recognition. Few studies specifically aimed to study reproductive coercion. Studies were set in a wide variety of countries, urban and rural areas, and examined a wide variety of populations.

Table 4. Summary of Implications Offered Regarding Reproductive Coercion in International Settings.

| First Author (year) Methodology | Setting and Sample | Perpetrator | Implications | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clark (2008) Cross-sectional survey |

Family planning clinics in Jordan 353 literate, ever-married women aged 15-49 |

Both | Healthcare providers should be aware of the challenges women face in trying to control fertility. Involve husbands and family members in family planning services to garner support. |

QI |

|

Char (2010) Qualitative |

Rural India 60 families (180 family members) from 12 villages |

In-laws | Family planning services can facilitate autonomous decisions by a couple, without influence of family members, thus transforming family dynamics. | QII |

|

Gupta (2012) Cross-sectional survey |

Rural Cote d'Ivoire 981 Ivorian women aged 18 years and older who reported having a male partner and a current source of stable income. |

In-laws | Health care providers should consider the role of in-laws in family planning decisions, and should assess for reproductive coercion as well as abuse. Programs focusing on gender-based violence should consider the role of in-laws and should include outreach to and programs for in-laws in addition to women Programs should make attempts to address gender norms within families through efforts to address women's economic empowerment and decision-making ability. |

QI |

|

McCauley (2014) Cross-sectional survey |

Rural Cote d'Ivoire 953 Ivorian women aged 18 years and older who reported having a male partner |

Both | Reproductive coercion has implications for women's mental health on a global level. Healthcare providers should screen for IPV and reproductive coercion as mental health indicators |

QI |

Studies in this review provide very limited data on prevalence of reproductive coercion, and minimal findings on associated factors. While international literature describes in-laws and relatives as perpetrators, male partners perpetrate more frequently. It is clear that these are different phenomena with different implications for policy and intervention; however, these behaviors may have similar outcomes for the woman, as suggested by McCauley et al (2014) in their analysis of PTSD and reproductive coercion. A wide range in prevalence of specific behaviors of reproductive coercion between and within studies may reflect the difficulty in defining reproductive coercion, and in drawing clear lines between what is coercion as opposed to pressure as opposed to routine disagreement between members of a couple or a family. Correlates of and risk factors for reproductive coercion vary by country, and some factors increase risk in one country but are protective in others, reflecting the impact context and environment can have when examining phenomena such as this. Some studies stratify findings by religion but when sufficient diversity in religious background was present to conduct statistical tests, this was not found to be a significant predictor (Raj et al. 2011). A preference for male children is suggested in several studies, possibly reflecting gender bias on a cultural level. Some studies describe specific tactics of reproductive coercion, though these findings are limited. Pressure to have an abortion is examined in several studies, but pressure not to have an abortion is overlooked. It is unclear if such pressure does not exist, or if it was not examined – perhaps due to the legal status of abortion in different countries. As is the case in American literature, there is a clear connection between reproductive coercion and IPV. Some studies do examine the relationship between IPV and unintended pregnancy, which is likely to be a function of reproductive coercion, but it is not specifically examined in the international literature.

Implications

The findings of the studies included in this review are challenging to generalize because the regions in which these studies were conducted (Africa, South Asia, the Middle East, and the US) vary greatly in terms of gender norms, religious influence in individual decision-making, literacy and socio-economic status, social and legal status of women, access to contraception, and legality of abortion. Findings related to abortion were limited to three studies that all reported pressure to terminate pregnancies in countries (India and China) where male child preference, and sex selective abortion are common (Mohanty and Rajbhar 2014; Zhu, Lu, and Hesketh 2009). Further studies should be conducted to explore abortion coercion in diverse settings. There are several important themes that should direct further reproductive coercion research, both in the US and abroad: the involvement of extended family members in reproductive coercion; the ways in which reproductive technologies can facilitate or mitigate reproductive coercion; and the intersection of reproductive coercion, IPV, and mental health.

The perpetrator of reproductive coercion is often a male partner, but may also be a member of the extended family such as a mother- or sister-in-law. This is an important finding as researchers attempt to develop interventions to address reproductive coercion, and unintended pregnancy. Interventions must target women, their partners, their extended families, and community social norms in order to minimize or eliminate reproductive coercion. Healthcare providers must be cognizant of the influence that family members play in a woman's reproductive life – additional research is needed to guide interventions that could be utilized by healthcare providers to empower women in the context of her own family, particularly if she is suffering reproductive coercion.

Themes that were uncovered in international settings may also be occurring among immigrant communities in the United States. One qualitative study not included in the analysis because it examined Indian women in an immigrant context, reported pregnancy coercion from both male and female in-laws and husbands, specifically for male children (Puri et al. 2011). Women in this study described less pressure from husbands for a male child with their first pregnancy, but increasing pressure with time, including pressure to space pregnancies closely and to use sex determination and sex selection services (including abortion for female fetuses). This study highlights the ways in which current reproductive technologies (sex selection, IVF, elective abortion) can be both empowering to women and a source of reproductive coercion if a family member or partner demands abortion of a female fetus, or sex selective IVF (Puri et al. 2011). More research is needed to examine the role of new reproductive technologies on reproductive coercion, and unintended or unwanted pregnancies. International studies provide important insights into the ways minority immigrant groups experience reproductive coercion, particularly considering that these groups may not be studied in depth within their host country as they make up a small proportion of the total population.

Similar to the American literature, an international study on reproductive coercion demonstrated a relationship between IPV, mental health, and reproductive coercion. Interventions for gender-based violence should include screening for reproductive coercion and confidential counseling for family planning services. Further research is needed to develop interventions for female survivors of intimate partner violence and gender-based violence that address reproductive coercion, potential unintended pregnancies, and the mental health consequences of each of these phenomena – individually and cumulative lifetime exposures.

Interventions that seek to prevent reproductive coercion, or mitigate its effects, must take into account women's status in society including both her legal rights and the social expectations for her reproductive behaviors. Researchers must consider who the appropriate target populations would be for intervention beyond women themselves; this might include older women (mothers-in-law), community leaders, husbands, or men's groups (Shattuck, et all 2011). Community and social norm interventions may become important methods for transforming attitudes around women's reproductive behavior, particularly in areas where there is systemic gender inequality resulting in pressures on women's childbearing related to number of offspring, and male child preference (Adjiwanou & N'Bouke, 2015; Puri et al., 2011).

Studies that considered abortion pressure found that women were sometimes pressured to have an abortion, though no studies reported women being prevented from accessing abortion (by a relative or partner) when they desired one. This is in contrast to literature set in the United States, in which findings about pressure to have an abortion (Chibber et al. 2014; Finer et al. 2005; Foster et al. 2012; Hathaway et al. 2005; Miller et al. 2007; Moore et al. 2010; Nikolajski et al. 2015; Silverman et al. 2010; Thiel de Bocanegra et al. 2010) are balanced with findings about pressure not to have an abortion or preventing women from accessing abortion services (Hathaway et al. 2005; Herrman 2007; Moore et al. 2010; Nikolajski et al. 2015; Silverman et al. 2010; Thiel de Bocanegra et al. 2010), and women in coercive or abusive relationships who have abortions most often do so in an attempt to end the relationship, not due to pressure from partners (Chibber et al. 2014). Further research is needed to explore reproductive coercion for abortion in international settings, particularly across regions with differential access to safe, legal abortion. Social, cultural, and legal factors may influence what kinds of pressures are placed on women regarding abortion.

Limitations of this Review

This review used a broad search strategy and collected a sizable amount of literature on the topic of reproductive coercion. The search was limited to the past 10 years to cover the five years prior to and after the identification of reproductive coercion as a distinct concept in the literature, but removing time limits may yield a larger number of relevant studies. Research in languages other than English was excluded, which may have limited the findings, especially in a review of international literature. This review included all studies that address reproductive coercion, or its constituent behaviors, in any country outside the United States. The countries in which the studies were conducted are varied in terms of the status of women in society, reproductive rights, and social norms for family planning. This diversity limits the comparability, and generalizability of the findings. Reproductive coercion as a concept is relatively new to the literature on women's health (Miller et al. 2010; Moore et al. 2010), resulting in few studies that explicitly address reproductive coercion as a concept. This review did not consider the case of mass rape in genocidal campaigns and the accompanying forced pregnancies that may occur as a means of control or of purposeful population growth. There is overlap in this concept with the study of reproductive coercion, but it addresses a broader phenomenon that is beyond the scope of this review.

Suggestions for Further Research

Research in the United States focuses heavily on the intersection between reproductive coercion and unintended pregnancy (in this context, referring to pregnancy that is unintended by the female partner) (Borrero et al. 2015; Miller et al. 2010, 2012, 2014; Sutherland et al. 2015). Prevention of unintended pregnancy is a policy priority in the United States as well as internationally, and intuitively there is a clear connection between the behaviors of reproductive coercion and the outcome of unintended pregnancy. No studies in the international literature presented findings related to unintended pregnancy.

Further research is needed to better understand the phenomenon of reproductive coercion, and the ways different coercive behaviors manifest in the United States and diverse communities abroad in order to develop effective interventions to mitigate and prevent reproductive coercion. Most of the findings in this review were incidental findings in studies that aimed to examine a different phenomenon besides reproductive coercion. Research specifically aiming to examine reproductive coercion would be beneficial to this emerging area of knowledge. Qualitative work is very limited in this area, and should be conducted to ensure that concepts developed in the United States adequately address the way reproductive coercion manifests in diverse settings. Additional qualitative research is important in order to better understand the phenomenon of reproductive coercion, particularly in non-Western settings where gender roles and social norms around sexuality and reproductive health may be markedly different than where the concept was initially developed. Specific behaviors such as “disapproval of contraception” must be explored further to understand whether this behavior is exclusively coercive or may encompass more benign motivations such as concern about health risks. We recommend further validation of the Miller instrument for reproductive coercion in international settings. Stratification of findings by religion, caste, geographic region, and other potential predictors of reproductive coercion may help illuminate potential risk factors. Further examination of immigrant women and the experience of their reproductive decision-making after forced or voluntary migration, as well as in post-conflict settings, will be a valuable addition to the literature. Additional studies should explore the resistance strategies currently used by women experiencing reproductive coercion, the ways in which reproductive coercion manifests among sexual minority women, and men's role as perpetrators of reproductive coercion and their potential as allies for prevention. Finally, in areas where the concept is well understood and risk factors have been identified, researchers should begin to develop and test clinical and community-based interventions for reproductive coercion.

Conclusion

Reproductive coercion is an emerging area of research, with limited studies published outside the United States. The majority of data currently available is observational, and thus little is known about causality or chronology of events in the lives of women who experience reproductive coercion. Though there are themes that emerge across different countries and communities, additional research in diverse settings is needed to both understand reproductive coercion in international settings, and to develop effective clinical and community interventions for treatment and prevention. Further qualitative and quantitative study of reproductive coercion will bring to light many unexplained relationships among risk and protective factors that will inform interventions for providers and advocates. This area of research is critically important in order to better understand the relationship between interpersonal violence and unintended pregnancy. Further international research into reproductive coercion will help to establish connections between factors that influence women's reproductive health, autonomy and safety.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This publication was made possible by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) which is funded in part by Grant Number TL1 TR001078 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS or NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

This paper was originally presented at the Workshop on Women's Health in Global Perspective, George Mason University, Arlington, VA, March 3, 2016.

Contributor Information

Karen Trister Grace, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, an Adjunct Instructor at Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies, and is in clinical midwifery practice at Mary's Center in Adelphi, MD.

Christina Fleming, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, an Adjunct Instructor at Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies, and is in clinical midwifery practice at Providence Hospital in Washington, D.C.

References

- Adjiwanou Vissého, N'Bouke Afiwa. Exploring the Paradox of Intimate Partner Violence and Increased Contraceptive Use in Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in family planning. 2015;46(2):127–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2015.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrero Sonya, et al. It Just Happens: A Qualitative Study Exploring Low-Income Women's Perspectives on Pregnancy Intention and Planning. Contraception. 2015;91(2):150–56. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton Candace W, Carlyle Kellie E. Screening and Intervening: Evaluating a Training Program on Intimate Partner Violence and Reproductive Coercion for Family Planning and Home Visiting Providers. Family & community health. 2015;38(3):227–39. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesario Sandra, Morin Karen, Santa-Donato Anne. Evaluating the Level of Evidence of Qualitative Research. Journal of obstetric, gynecologic, and neonatal nursing : JOGNN / NAACOG. 2002;31(6):708–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Char Arundhati, Saavala Minna, Kulmala Teija. Influence of Mothers-in-Law on Young Couples' Family Planning Decisions in Rural India. Reproductive health matters. 2010;18(35):154–62. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(10)35497-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibber Karuna S, Biggs M Antonia, Roberts Sarah CM, Foster Diana Greene. The Role of Intimate Partners in Women's Reasons for Seeking Abortion. Women's Health Issues. 2014;24(1):e131–38. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Cari Jo, et al. Intimate Partner Violence and Interference with Women's Efforts to Avoid Pregnancy in Jordan. Studies in family planning. 2008;39(2):123–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Lindsay E, Allen Rebecca H, Goyal Vinita, Raker Christina, Gottlieb Amy S. Reproductive Coercion and Co-Occurring Intimate Partner Violence in Obstetrics and Gynecology Patients. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2014;210(1):42.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer Lawrence B, Frohwirth Lori F, Dauphinee Lindsay A, Singh Susheela, Moore Ann M. Reasons U.S. Women Have Abortions: Quantitative and Qualitative Perspectives. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2005;37(3):110–18. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.110.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster Diana Greene, Gould Heather, Taylor Jessica, Weitz Tracy A. Attitudes and Decision Making Among Women Seeking Abortions at One U.S. Clinic. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2012;44(2):117–24. doi: 10.1363/4411712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Falb K, Kpebo D, Annan J. Abuse from in-Laws and Associations with Attempts to Control Reproductive Decisions among Rural Women in Cote d'Ivoire: A Cross-Sectional Study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2012;119(9):1058–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway Jeanne E, Willis Georgianna, Zimmer Bonnie, Silverman Jay G. Impact of Partner Abuse on Women's Reproductive Lives. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2005;60(1):42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrman Judith W. Repeat Pregnancy in Adolescence: Intentions and Decision Making. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2007;32(2):89–94. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000264288.49350.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Journal of Mixed Methods Research. Review Criteria. n.d. Retrieved April 9, 2015 ( http://www.uk.sagepub.com/journals/Journal201775/manuscriptSubmission)

- Kadir Muhammad Masood, Fikree Fariyal F, Khan Amanullah, Sajan Fatima. Do Mothers-in-Law Matter? Family Dynamics and Fertility Decision-Making in Urban Squatter Settlements of Karachi, Pakistan. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2003;35(4):545–58. doi: 10.1017/s0021932003005984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmerski Traci, et al. Use of Reproductive and Sexual Health Services Among Female Family Planning Clinic Clients Exposed to Partner Violence and Reproductive Coercion. Maternal and child health journal. 2015;19(7):1490–96. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati Alessandro, et al. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2009;62(10):e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley Heather L, Dick Rebecca N, et al. Differences by Sexual Minority Status in Relationship Abuse and Sexual and Reproductive Health Among Adolescent Females. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55(5):652–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley Heather L, et al. Sexual and Reproductive Health Indicators and Intimate Partner Violence Victimization Among Female Family Planning Clinic Patients Who Have Sex with Women and Men. Journal of Women's Health. 2015;24(8):621–28. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley Heather L, Falb Kathryn L, Streich-Tilles Tara, Kpebo Denise, Gupta Jhumka. Mental Health Impacts of Reproductive Coercion among Women in Cote d'Ivoire. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2014;1271(1):55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Elizabeth, et al. Male Partner Pregnancy-Promoting Behaviors and Adolescent Partner Violence: Findings from a Qualitative Study with Adolescent Females. Ambulatory pediatrics : the official journal of the Ambulatory Pediatric Association. 2007;7(5):360–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Elizabeth, et al. Pregnancy Coercion, Intimate Partner Violence and Unintended Pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(4):316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Elizabeth, et al. A Family Planning Clinic Partner Violence Intervention to Reduce Risk Associated with Reproductive Coercion. Contraception. 2011;83(3):274–80. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Elizabeth, et al. Exposure to Partner, Family, and Community Violence: Gang-Affiliated Latina Women and Risk of Unintended Pregnancy. Journal of Urban Health. 2012;89(1):74–86. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9631-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Elizabeth, et al. Recent Reproductive Coercion and Unintended Pregnancy among Female Family Planning Clients. Contraception. 2014;89(2):122–28. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty Sanjay K, Rajbhar Mamta. Fertility Transition and Adverse Child Sex Ratio in Districts of India. Journal of biosocial science. 2014;46(6):753–71. doi: 10.1017/S0021932013000588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore Ann M, Frohwirth Lori, Miller Elizabeth. Male Reproductive Control of Women Who Have Experienced Intimate Partner Violence in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:1737–44. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolajski Cara, et al. Race and Reproductive Coercion: A Qualitative Assessment. Women's health issues. 2015;25(3):216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okunlola MA, Owonikoko KM, Roberts OA, Morhason-Bello IO. Discontinuation Pattern among IUCD Users at the Family Planning Clinic, University College Hospital, Ibadan. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;26(2):152–56. doi: 10.1080/01443610500443667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri Sunita, Adams Vincanne, Ivey Susan, Nachtigall Robert D. ‘There Is Such a Thing as Too Many Daughters, but Not Too Many Sons’: A Qualitative Study of Son Preference and Fetal Sex Selection among Indian Immigrants in the United States. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;72(7):1169–76. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj Anita, et al. Abuse from in-Laws during Pregnancy and Post-Partum: Qualitative and Quantitative Findings from Low-Income Mothers of Infants in Mumbai, India. Maternal and child health journal. 2011;15(6):700–712. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0651-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romito Patrizia, et al. Violence in the Lives of Women in Italy Who Have an Elective Abortion. Women's Health Issues. 2009;19(5):335–43. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salam Abdus, Alim Abdul, Noguchi Toshikuni. Spousal Abuse against Women and Its Consequences on Reproductive Health: A Study in the Urban Slums in Bangladesh. Maternal and child health journal. 2006;10(1):83–94. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman Jay G, et al. Male Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence and Involvement in Abortions and Abortion-Related Conflict. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1415–17. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.173393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup Donna F, et al. Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology: A Proposal for Reporting. Meta-Analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group. Jama. 2000;283(15):2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland Melissa A, Fantasia Heidi Collins, Fontenot Holly. Reproductive Coercion and Partner Violence among College Women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2015;44(2):218–27. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel de Bocanegra Heike, Rostovtseva Daria P, Khera Satin, Godhwani Nita. Birth Control Sabotage and Forced Sex: Experiences Reported by Women in Domestic Violence Shelters. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(5):601–12. doi: 10.1177/1077801210366965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay Ushma D, Dworkin Shari L, Weitz Tracy A, Foster Diana Greene. Development and Validation of a Reproductive Autonomy Scale. Studies in family planning. 2014;45(1):19–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke Jan P, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS medicine. 2007;4(10):e297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Jiuling, Guo Sufang, Qu Chuanyan. Domestic Violence against Women Seeking Induced Abortion in China. Contraception. 2005;72(2):117–21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakar Rubeena, Zakar Muhammad Z, Mikolajczyk Rafael, Krämer Alexander. Intimate Partner Violence and Its Association with Women's Reproductive Health in Pakistan. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2012;117(1):10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Wei Xing, Lu Li, Hesketh Therese. China's Excess Males, Sex Selective Abortion, and One Child Policy: Analysis of Data from 2005 National Intercensus Survey. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2009;338:b1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]