Abstract

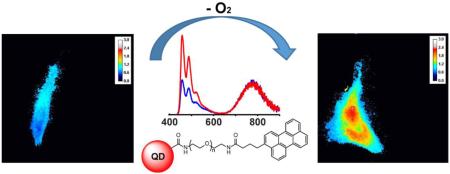

A quantum-dot based ratiometric fluorescent oxygen probe for the detection of hypoxia in live cells is reported. The system is comprised of a water-soluble near-infrared emissive quantum dot conjugated to perylene dye. The response to the oxygen concentration is investigated using enzymatic oxygen scavenging in water, while in vitro studies were performed with HeLa cells incubated under varying O2 levels. In both cases a significant enhancement in dye/QD emission intensity ratio was observed in the deoxygenated environment, demonstrating the possible use of this probe for cancer research.

Keywords: quantum dot, nanocrystal, fluorescence, perylene, hypoxia, cancer marker

Molecular oxygen plays a vital role in a broad range of chemical and biological reactions.1 While reactive oxygen species are toxic to all organisms,2 O2 is none-the-less necessary for ATP generation in aerobic cells3 and for several other physiological functions. Low O2 concentrations result in hypoxia, which is observed in tumor tissues4 due to the fact that cancer cells rapidly consume oxygen as they produce energy via a high rate glycolysis (i.e. the “Warburg Effect”).5 Significant efforts have been devoted to develop reliable techniques for the detection of oxygen as O2 levels are indicative of the physiological behavior of living systems. Furthermore, the quantification of oxygen is an indispensable part of environmental analysis, food packaging, and industrial monitoring.6

Oxygen has a high diffusion rate and a limited temperature-dependent solubility in aqueous solutions.7 These properties complicate sampling and necessitate real-time measurements. Various oxygen detection techniques have been reported based on chemical (Winkler titration),8, 9 electrochemical10 (such as the Clark electrode),11 and instrumental (GC or MRI)12, 13 methods. Many of these suffer from drawbacks such as relatively long response times or a lack of consistency, accuracy, or reversibility. Worst of all is the potential consumption of oxygen during the detection process. Recently, optical methods have attracted attention since they offer reversible responses with no electrical interferences and generally do not annihilate the analyte. Furthermore, they are inexpensive and easy to miniaturize, and may be used in a relatively noninvasive manner.14–16

Semiconductor quantum dots (QDs) are frequently used in bio-analytical techniques due to their highly robust physical properties. While often used for imaging purposes, quantum dots are also valuable components of fluorescent sensing systems for metabolites such as oxygen and pH, etc.17–19 Here we report a probe for the in vitro detection of oxygen based on non-toxic near IR-emissive QDs coupled to a novel perylene dye derivative. This platform offers several advantages over other optical reporters. Specially, the use of near-IR emissive quantum dots reduces photobleaching and enhances the signal for through-tissue imaging. We have also avoided incorporating ubiquitous CdSe/ZnS QDs in favor of a cadmium-free AgInS2/ZnS nanocrystals to mitigate issues with toxicity. As the supermolecular size and surface passivation of core/shell quantum dots removes their environmental sensitivity, the nanocrystals were conjugated to an oxygen-sensitive perylene dye derivative. The result is an O2 sensor that has a ratiometric fluorescent response that is fully quantitative and eliminates problems with light source fluctuations and emission scattering that are issues with single-response “turn-on” or “turn-off” probes. Finally, we demonstrate that the sensor may be used to detect hypoxia in the cytosol of live HeLA cells.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Instrumentation

Perylene (≥99.5%), N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC, 99%), N-hydroxysuccinimide (98%), triphenylphosphine (99%), hydrazine monohydrate (≥98%), 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE, ≥99%), titanium (IV) chloride (TiCl4, ≥99%), xylenes (≥98.5%), diethylene glycol (≥99%), trimethylamine (TEA, ≥99%), ethyl acetate (EtOAc, 99.8%), dichloromethane (DCM, ≥99.8%) and hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium sulfate (anhydrous, >99%), potassium hydroxide (≥85%) and tetrahydrofuran (THF, 99.9%) were purchased from Fisher Chemicals. Succinic anhydride (99%) was purchased from Acros Organics. Where indicated, solvents were dried using activated molecular sieves (3Å, Sigma-Aldrich). The QD-functionalization reagent methoxypolyethylene glycol 350 carbodiimide (MPEG 350 CD),20 and 40% octylamine-modified poly(acrylic acid) (PAA)21, 22 were prepared according to previously published protocols. The precursor N3-PEG400-amine was prepared according to ref.23. NMR spectra (1H and 13C) were recorded on a Bruker Avance DRX 400 NMR spectrometer. UV/vis absorbance spectra were measured using a Varian Cary 300 Bio UV/vis spectrophotometer, and fluorescence emission spectra were obtained using a custom-designed Horiba Jobin Yvon FluoroLog spectrophotometer. Oxygen levels in aqueous solutions were measured using SevenGo pro™ dissolved oxygen meter SG6 with inLab® 605 O2-sensor from Mettler Toledo. HeLa cells (CCL-2) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM, 10-014 CV) and 0.25% trypsin/2.21 mM EDTA were purchased from Corning Cellgro®. MEM non-essential amino acids (11140) and HEPES (15630-080) were purchased from Gibco®. Micropipette preparation glass bottom culture dishes (P50G-1.5-14-F) were purchased from Matek Corporation (Ashlan, MA). XenoworksTM Microinjection Systems, P-1000 pipette puller and borosilicate glass tubes (BF100-78-10) were used for microinjections (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA).

Perylene-PEGamine

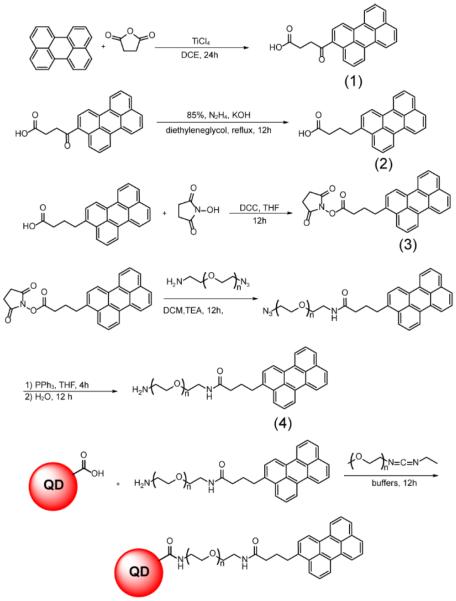

The synthesis of water-soluble perylene-PEGamine dye is outlined in Scheme 1 and is detailed below. All NMR data are provided in the supporting information in Figures S1–S5.

Scheme 1.

Perylene-PEGamine synthesis and conjugation to QDs.

4-oxo-4-(perylene-3-yl)butanoic acid (1)

Perylene (0.252 g, 1 mmol) and succinic anhydride (0.152 g, 1.5 mmol) were dissolved in dry DCE (5 mL). The solution kept stirring under a nitrogen atmosphere and was immersed in an ice bath. A solution of TiCl4 (0.15 mL, 1.3 mmol) in 1 mL of DCE was added dropwise to the solution, and the mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The next day the product hydrolyzed by adding dilute HCl and the precipitate was collected by filtration. The product was extracted into EtOAc (20 mL) and washed with DI water (3×15 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The solid brown substance was recrystallized from 25 mL of xylene after heating to 140 °C. The brown powder was separated by centrifuge and dried under reduced pressure (61% yield).

4-(perylene-3-yl)butanoic acid (2)

4-oxo-4-(perylene-3-yl)butanoic acid (0.177 g, 0.5 mmol), KOH (0.224g, 4 mmol), and hydrazine monohydrate 98% (0.24 mL, 5 mmol, warning: highly toxic substance) were dissolved in 5 mL of diethylene glycol, followed by 90 minutes reflux at 180 °C. After 1.5 h the excess water and hydrazine were drained from condenser allowing the temperature to rise to 200 °C, and the refluxing was continued overnight. The next day the solution was poured into an ice bath and acidified to pH 6 using 3M HCl. Then the product was extracted with 20 mL EtOAc, and washed with DI water (3×15 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The product was used for the next step without further purification (70% yield).

2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 4-(perylene-3-yl) butanoate (3)

4-(perylene-3-yl)butanoic acid (0.102 g, 0.3 mmol) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (34.5 mg, 0.3 mmol) were dissolved in dry THF (10 mL). The mixture was placed in an ice bath and a THF solution (2 mL) of DCC (61.9 mg, 0.3 mmol) was added dropwise, followed by stirring overnight at room temperature. The next day the white precipitate (1,3-dicyclohexylurea) was filtered out and the filtrate was subjected to reduced pressure to remove THF, resulting in a solid brown powder. The pure product was recrystallized from EtOH (62% yield).

N-poly(ethylene)glycol amine-4-(perylene-3-yl)butanamide (4)

2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 4-(perylene-3-yl) butanoate (44.9 mg, 0.1 mmol) and N3-PEG400-amine (42.4 mg, 0.1 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL of dry DCM. 14 μL of TEA (0.1 mmol) was added to the solution and it was stirred under nitrogen at room temperature overnight. The next day solvent was removed under reduced pressure and triphenylphosphine (26.2 mg, 0.1 mmol was added, followed by 10 mL of THF. The mixture was stirred 4h at room temperature, after which 0.5 mL of DI water was added to the mixture and the solution was kept stirring at room temperature overnight. The next day the solvent was removed by reduced pressure and 15 mL of 1M HCl was added to the substance. The aqueous dye solution was filtered to separate the insoluble triphenylphosphine oxide. The filtrate was washed with Et2O (3×15 mL) and then 3 g of KOH was added to the solution, followed by extraction of the product with DCM (6×10 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and was subsequently removed under reduced pressure to obtain pure product in the form of an intense yellow viscous oily liquid (60% yield).

AgInS2/ZnS QDs Synthesis and Water Solubilization

AgInS2/ZnS core/shell QDs were synthesized according to previously published protocol.24 Approximately 0.5 g of the crude sample was processed by addition of excess ethanol to induce flocculation. The supernatant was discarded and the precipitate was dried under reduced pressure. Next, 30 mg of amphiphilic 40% octylamine-modified PAA was added to the QDs followed by ~3 mL of dry chloroform. The solution was sonicated for several minutes to dissolve the polymer completely. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and 0.1 M NaoH solution was added to disperse the QDs into water. To remove the excess polymer, the solution was dialyzed to neutrality using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (100,000 MWCO) from Millipore.

Perylene-PEGamine Conjugation to QDs

AgInS2/ZnS QDs were activated by adding 10 mg of MPEG 350 carbodiimide to 0.5 mL of water-solubilized QDs and stirring for 20 min. A solution of perylene-PEGamine (4) dissolved in pH 8 phosphate buffer was prepared and added dropwise to the activated QDs solution until the desired dye emission was achieved. The pH of the solution was adjusted at 8 by adding phosphate buffer, and it was stirred overnight. The next day the solution was dialyzed using a dialysis tube (Float-A-Lyzer G2, 20 kD MWCO, Spectrum Labs) until all the unconjugated dye eluted out. Despite the fact that the perylene emission overlaps the QD absorption, there was minimal observation of FRET energy transfer, which is consistent with the fact that QDs are poor acceptors to dye donors.25

Enzymatic Oxygen Scavenging Titration System

Two separate experiments were conducted to measure the probe's response to varying O2 levels. In the first, the emission of the probe in Tris-HCL pH 7.4 buffer was measured and compared to the same in a screw top cuvette containing an enzyme mixture composed of glucose (10 mg/mL), glucose oxidase (0.5 mg/mL), catalase (0.08 mg/mL), and ATP (3 mM), that was allowed to equilibrate for 20 min. The O2 levels were measured using Mettler Toledo SG6-SevenGo pro™ dissolved oxygen meter with InLab® 605 O2 sensor. The oxygen concentration dropped from 6.8 ppm to 0.01 ppm, which confirms the efficiency of the oxygen scavenging system. A second experiment was conducted under identical enzymatic conditions with the glucose initially absent. Next, glucose was added in small portions in 20 min intervals, after which time the emission spectrum was recorded. Unfortunately, we are not certain of the absolute O2 concentrations as a result, although we assume that they still span the ~6.8 to 0.01 ppm range. The excitation wavelength of 425 nm was chosen to co-excite both chromophores simultaneously in these experiments. The fluorescence responses were quantified by dividing the integrated emission in the visible range (originating from perylene) over the integrated emission in the NIR range (originating from the QD).

Cell Culture

HeLa cells were maintained in DMEM (+) (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1× MEM non-essential amino acids and 15 mM HEPES) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The cells were passaged with 0.25% trypsin/2.21 mM EDTA. An MTT assay was performed according to the procedure in Ref. 26 to assess the toxicity of compound 4. Cells were exposed for 30 min to reflect the usage of the dye under experimental conditions.

Microinjection

HeLa cells were grown to 60–70% confluency in a glass bottom dish before microinjection and kept in either 19.8% O2 or 6.9% O2 for studies under ambient or low-level oxygen conditions, respectively. Micropipettes were prepared by the following parameters: heat, ramp-27; pull, 95; velocity, 27; time, 250; and pressure, 250. Micropipettes were loaded with the sensor solution by capillary action and the solution was injected into the cytosol by using the following microinjector parameters: transfer pressure, 17 hPa; injection width, 0.1 sec; injection pressure, 200 hPa.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Fluorescence images of the injected cells were acquired after 10 min using an epi-fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 200, Carl Zeiss, Inc.) equipped with an intensified CCD camera (XR Mega 10-S30CL ICCD, Stanford Photonic Inc.) modified with two LEDs for UV and white light (Prizmatix, Ltd.). All images were obtained with a 63×/1.25 N.A. EC Plan Neofluar oil-immersion objective (Carl Zeiss, Inc.). G365 nm and 427 nm (± 5) excitation filters were used to excite quantum dots and dye respectively. Emission filters (775 ± 70 nm and 472 ± 15 nm) were used to separately image and measure quantum dots and dye emission intensities. The same settings were used to acquire images in low and ambient levels of oxygen. All images are dark current corrected. Signal intensity was determined from ROIs in the cytoplasm using the Image J software (v 1.47) package.27 Note that the magnitudes of the dye/QD emission ratios from the fluorescence and microscopy experiments do not span the same range of values. This is due to differences in the method of collection, and the wavelength-dependent response of the CCD camera.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

There have been several reports on the development of QD-organic dye coupled chromophore sensors to create synergistic systems with the robust qualities of quantum dots and the analytical capabilities of organic dyes. As large core/shell QDs are mostly passive to their environment, they must be conjugated to a reporting chromophore to engender a quantifiable optical response to targeted analytes. Species of interest include proteases,28 biological thiols,29 as well as pH30 and O2 levels as these analytes are associated with cancer. Recently, McLaurin et al. developed a QD-based fluorescent sensor for O2 by conjugating oxygen-sensitive osmium complexes to CdSe/ZnS nanocrystals.31 They characterized FRET energy transfer from the QD to these ligands and demonstrated oxygen-dependent ratiometric emission. The benefits of these systems include high two-photon absorption cross sections and QD-to-chromophore FRET. However, osmium-containing compounds can be expensive and toxic, have low emission quantum yields (~1%), and the probes did not respond to physiological O2 levels.

As such, the same group later used CdSe/ZnS-palladium(II) porphyrin coupled chromophores to profile oxygen levels in vivo, although the gas was quantified via modulation of the Pd(II)-porphyrin luminescence lifetime rather than emission intensity.32, 33 Amelia et al. demonstrated oxygen sensing using CdSe/ZnS QDs functionalized with pyrene,34 an organic chromophore with a well-characterized O2 sensitivity35, 36 and reduced toxicity.37, 38 However, the design of the system resulted in significant QD quenching and was reported to function only in an organic solvent; clearly this precludes applications in many biological systems.

Our group sought to demonstrate oxygen quantification in a biological system using a fully fluorescence-based approach with a singular non-toxic platform. Analyte-dependent ratiometric emission provides a simple output that can be realized using a coupled chromophore. To this end, we employed AgInS2/ZnS quantum dots due to their enhanced photostability, high brightness, and broad absorption spectra that allow for co-excitation of both chromophores (Figure S6). Furthermore, the use of a cadmium-free AgInS2/ZnS mitigates toxicity issues and offers advantages such as near-IR photoluminescence and a large Stokes shift that is desirable for in vivo imaging.

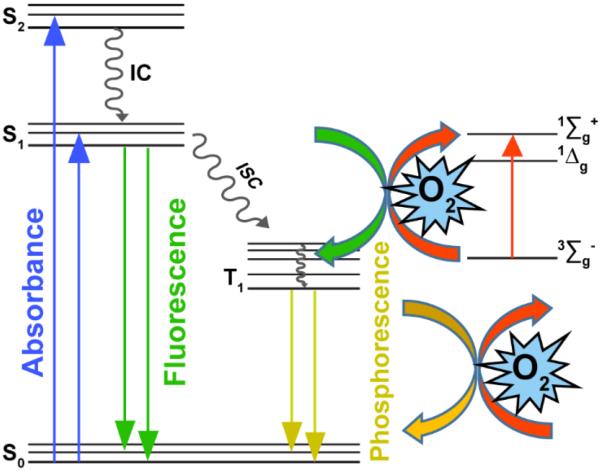

The choice of an O2-sensitive chromophore must take into account the dye's photophysical properties that engender oxygen-dependent emission efficiency. We will briefly review the many possibilities here although more detailed information can be found in recently published review papers.14–16, 39 Optical sensors for O2 can either be either colorometric (absorptive), although luminescence-based reporters are preferred for numerous reasons. They function by collisional quenching of the chromophore's excited state(s) by molecular oxygen40, 41 as depicted by the Jablonski diagram in Figure 1. Absorption of a photon eventually places the chromophore in the lowest singlet excited state S1. Next, many O2-sensitive dyes undergo non-radiative intersystem crossing to the lowest excited triplet state T1 followed by phosphorescence emission to the ground state. However, ground triplet state molecular oxygen (3Σg−) can act as an energy acceptor to non-radiatively quench the excited triplet state,42, 43 resulting in an O2-sensitive phosphorescence intensity. This mechanism is commonly observed in organometallic complexes such Pd porphyrins44 that have been commercialized for oxygen sensing.45 As we wish to avoid such metal complexes, we have examined the use of a chromophore that undergoes oxygen-assisted fluorescence quenching from the excited S1 to the T1 state.46 This mechanism of fluorescence-based sensing is commonly observed in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) due to their long-lived singlet excited states, which is necessary to observe diffusional quenching by O2.47

Figure 1.

Jablonski diagram of fluorescence and phosphorescence quenching by molecular O2. This study employs a perylene dye that undergoes fluorescence quenching by oxygen.

While pyrene is an attractive candidate in this regard,34 we wish to avoid UV excitation in cell studies. As such, a larger PAH (perylene) was employed.48 Perylene dyes can be excited in the visible range, are photostable,49 and have high emission quantum yields (0.89–0.99) in the blue-green region.50 Unfortunately the commercial availability of perylene dye derivatives is limited. As such, we developed a protocol to synthesize a water-soluble perylene-PEGamine that can be conjugation to aqueous QDs encapsulated with 40% octylamine-modified poly(acrylic acid). The method is shown in Scheme 1, which was successfully executed to synthesize a water-soluble perylene-PEGamine dye with a quantum yield of 0.68 ± 0.03 (Figure S7).51 The chromophore was also found to be non-toxic as shown in the results of the MTT assay (Figure S8). It was also found to permeate live cells, which engenders the possibility of using it as a “turn-on” sensor for cellular O2 levels. However, such systems cannot ever be fully quantitative as one cannot distinguish between, for example, low O2 levels in the nucleus of a live cell vs. the inability of the chromophore to bypass the nuclear envelope. This issue is addressed by conjugating the perylene derivative to AgInS2/ZnS QDs to allow for the oxygen-insensitive dot emission to act as an internal calibration standard. As such, we can ascertain whether minimal perylene emission from the interior of a live cell is due to high O2 content vs. a low density of delivered coupled chromophores.

The ratiometric QD-dye probe was prepared using neutral carbodiimide coupling reagents and purified by dialysis to remove byproducts any free perylene dye. Next, the probe's response to O2 levels was quantified. This was attempted by a variety of methods, including sparging the solution with nitrogen and the freeze-pump-thaw technique. However, the results were never consistent, likely due to perturbation of the coupled chromophore as QD precipitation was occasionally observed with sparging. As such, we investigated the use of an enzymatic system that offers rapid O2 removal and the ability to maintain the anoxia for long periods of time. One of the most well-established schemes is based on the oxidation of glucose with glucose oxidase. In this ATP-driven process gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide are produced by the action of glucose oxidase on glucose. Catalase removes the H2O2 by decomposing it into water and oxygen; note that there is an overall net loss of O2 as shown in equations 1 & 2:

| (1) |

| (2) |

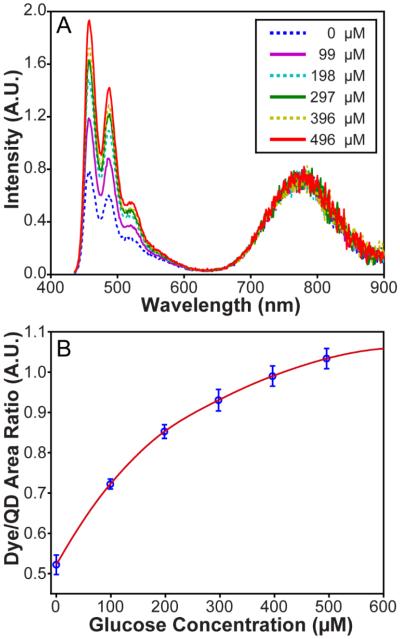

A solution composed of the QD-based oxygen probe, glucose oxidase, catalyse, and ATP was titrated with increasing quantities of a glucose in 20 min intervals to progressively lower the O2 concentration. The fluorescent response of the sensor shown in Figure 2A was quantified by fitting multiple Gaussian functions to calculate the integrated dye:QD emission ratio. As can be seen in Figure 2B, the dye:QD ratio increased by adding glucose until complete deoxygenation occurred at which point the response was saturated. The overall alteration of the emission ratio is >100% over a measured oxygen concentration range of 6.8 to 0.01 ppm as shown in Figure S9. As such, the coupled perylene-QD chromophore can ratiometrically respond to physiologically relevant O2 levels in the visible-to-NIR region of the spectrum.

Figure 2.

(a) Emission of the sensor in response to decreasing oxygenation of the solution due to increasing glucose concentration (inset) that is the substrate of an enzymatic oxygen scavenging system. (b) Dye/QD integrated emission ratio in response to the addition of glucose to the enzymatic oxygen scavenging system.

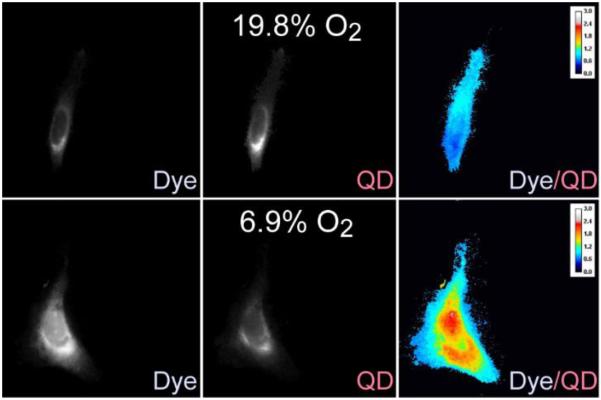

We investigated the probe response to alterations of oxygen concentration in vitro. As discussed previously, the water-soluble perylene-PEGamine dye is cell permeable; however, the QD-dye conjugate isn't and needed to be microinjected into cells. With this issue resolved, we next investigated several methods to control the oxygen levels in HeLa cells. First, incubation of the cells in the presence of the enzymatic oxygen scavenger system failed due to cell death. As a result, we tried to image the cells immediately after exposure to the enzyme mixture. However, no effect was observed, which we believe is due to the fact that equilibrium in the gas levels was not achieved over the short time interval. Despite these failures, we were able to demonstrate in vitro O2 quantification from two sets of HeLa cells that were cultured overnight under 6.9% and 19.8% O2 concentrations. Next, they were microinjected with the QD-perylene dye, and wavelength-selective microscopic images were obtained of the cells using separate bandpass filters for the QD and dye channels. As shown in Figure 3, there was a 30% enhancement in the intensity of the dye/QD signal in the hypoxic cells; the detailed changes in the intensities of the QD and dye signals are quantified for 13 different microinjected cells in Table S1 of the supporting information. As such, these control experiments demonstrate the potential use of a QD-perylene dye conjugate for the ratiometric measurement of hypoxia in live cells, which is a biological indicator of cancer.

Figure 3.

Ratiometric response of the sensor to hypoxia in HeLa cells incubated under 19.8% O2 (top row) and hypoxic 6.9% O2 (bottom row) levels overnight. Emission from perylene dye (472 nm) was observed due to visible 427 nm excitation, while the QD channel was observed at 775 nm using 365 nm excitation.

CONCLUSIONS

A fluorescent ratiometric oxygen probe was reported based O2 modulation of the fluorescence of perylene dye conjugated oxygen-insensitive near-IR emitting AgInS2/ZnS QDs. An enzymatic system composed of glucose, glucose oxidase, catalase and ATP was used to deoxygenate the samples which proved to highly robust and reproducible compared to sparging the solution or the freeze-pump-thaw technique. A >100% increase in dye:QD ratiometric signal was observed upon deoxygenation from ppm to 0.01 ppm. In vitro measurement were conducted by microinjection of the probe into live HeLa cells incubated under ambient and hypoxic oxygen levels overnight, which demonstrates the possibility of using this O2 sensor for cancer detection and research.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

PTS would like to thank support by Colgate-Palmolive, the Chicago Biomedical Consortium with support from the Searle Funds at the Chicago Community Trust, as well as the University of Illinois at Chicago. LWM was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM081030).

Funding Sources Colgate-Palmolive, the Chicago Biomedical Consortium, the National Institutes of Health, and the University of Illinois at Chicago.

ABBREVIATIONS

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- MEM

minimal essential medium

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid.

Footnotes

Additional spectroscopic and NMR data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. / All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- (1).Lane N. Oxygen: the molecule that made the world. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Fenchel T, Finlay B. Oxygen and the Spatial Structure of Microbial Communities. Biol. Rev. 2008;83:553–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Jez M, Rozman P, Ivanovic Z, Bas T. Concise Review: The Role of Oxygen in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Physiology. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015;230:1999–2005. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Noman MZ, Hasmim M, Messai Y, Terry S, Kieda C, Janji B, Chouaib S. Hypoxia: A Key Player in Antitumor Immune Response. A Review in the Theme: Cellular Responses to Hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2015;309:C569–579. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00207.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Thorne JL, Campbell MJ. Nuclear Receptors and the Warburg Effect in Cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;137:1519–1527. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Cichello SA. Oxygen Absorbers in Food Preservation: A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015;52:1889–1895. doi: 10.1007/s13197-014-1265-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Battino R, Rettich TR, Tominaga T. The Solubility of Oxygen and Ozone in Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1983;12:163–178. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Helm I, Jalukse L, Leito I. A Highly Accurate Method for Determination of Dissolved Oxygen: Gravimetric Winkler Method. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2012;741:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Winkler LW. Die Bestimmung Des Im Wasser Gelösten Sauerstoffes. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1888;21:2843–2854. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hutton L, Newton ME, Unwin PR, Macpherson JV. Amperometric Oxygen Sensor Based on a Platinum Nanoparticle-Modified Polycrystalline Boron Doped Diamond Disk Electrode. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:1023–1032. doi: 10.1021/ac8020906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Clark LC, Jr., Wolf R, Granger D, Taylor Z. Continuous Recording of Blood Oxygen Tensions by Polarography. J. Appl. Physiol. 1953;6:189–193. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1953.6.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Swinnerton JW, Linnenbom VJ, Cheek CH. Determination of Dissolved Gases in Aqueous Solutions by Gas Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 1962;34:483–485. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Christen T, Bolar DS, Zaharchuk G. Imaging Brain Oxygenation with MRI Using Blood Oxygenation Approaches: Methods, Validation, and Clinical Applications. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1113–1123. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Wang XD, Wolfbeis OS. Optical Methods for Sensing and Imaging Oxygen: Materials, Spectroscopies and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:3666–3761. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00039k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wang XD, Chen HX, Zhao Y, Chen X, Wang XR, Chen X. Optical Oxygen Sensors Move Towards Colorimetric Determination. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2010;29:319–338. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Papkovsky DB, Dmitriev RI. Biological Detection by Optical Oxygen Sensing. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:8700–8732. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60131e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Petryayeva E, Algar WR, Medintz IL. Quantum Dots in Bioanalysis: A Review of Applications across Various Platforms for Fluorescence Spectroscopy and Imaging. Appl. Spectrosc. 2013;67:215–252. doi: 10.1366/12-06948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Silvi S, Credi A. Luminescent Sensors Based on Quantum Dot-Molecule Conjugates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:4275–4289. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00400k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Stanisavljevic M, Krizkova S, Vaculovicova M, Kizek R, Adam V. Quantum Dots-Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer-Based Nanosensors and Their Application. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015;74:562–574. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.06.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Shen H, Jawaid AM, Snee PT. Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Carbodiimide Coupling Reagents for the Biological and Chemical Functionalization of Water-Soluble Nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2009;3:915–923. doi: 10.1021/nn800870r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Wu XY, Liu HJ, Liu JQ, Haley KN, Treadway JA, Larson JP, Ge NF, Peale F, Bruchez MP. Immunofluorescent Labeling of Cancer Marker Her2 and Other Cellular Targets with Semiconductor Quantum Dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:41–46. doi: 10.1038/nbt764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Chen Y, Thakar R, Snee PT. Imparting Nanoparticle Function with Size-Controlled Amphiphilic Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3744–3745. doi: 10.1021/ja711252n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Schwabacher AW, Lane JW, Schiesher MW, Leigh KM, Johnson CW. Desymmetrization Reactions: Efficient Preparation of Unsymmetrically Substituted Linker Molecules. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:1727–1729. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Shamirian A, Appelbe O, Zhang QB, Ganesh B, Kron SJ, Snee PT. A Toolkit for Bioimaging Using near-Infrared AgInS2/ZnS Quantum Dots. J. Mat. Chem. B. 2015;3:8188–8196. doi: 10.1039/c5tb00247h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Clapp AR, Medintz IL, Fisher BR, Anderson GP, Mattoussi H. Can Luminescent Quantum Dots Be Efficient Energy Acceptors with Organic Dye Donors? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1242–1250. doi: 10.1021/ja045676z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Rajendran M, Yapici E, Miller LW. Lanthanide-Based Imaging of Protein-Protein Interactions in Live Cells. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:1839–1853. doi: 10.1021/ic4018739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to Imagej: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kim GB, Kim YP. Analysis of Protease Activity Using Quantum Dots and Resonance Energy Transfer. Theranostics. 2012;2:127–138. doi: 10.7150/thno.3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Shamirian A, Afsari HS, Wu DH, Miller LW, Snee PT. Ratiometric QD-FRET Sensing of Aqueous H2S in Vitro. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:6050–6056. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Snee PT, Somers RC, Nair G, Zimmer JP, Bawendi MG, Nocera DG. A Ratiometric CdSe/ZnS Nanocrystal pH Sensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13320–13321. doi: 10.1021/ja0618999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).McLaurin EJ, Greytak AB, Bawendi MG, Nocera DG. Two-Photon Absorbing Nanocrystal Sensors for Ratiometric Detection of Oxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12994–13001. doi: 10.1021/ja902712b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Lemon CM, Karnas E, Bawendi MG, Nocera DG. Two-Photon Oxygen Sensing with Quantum Dot-Porphyrin Conjugates. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:10394–10406. doi: 10.1021/ic4011168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lemon CM, Karnas E, Han X, Bruns OT, Kempa TJ, Fukumura D, Bawendi MG, Jain RK, Duda DG, Nocera DG. Micelle-Encapsulated Quantum Dot-Porphyrin Assemblies as in vivo Two-Photon Oxygen Sensors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:9832–9842. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Amelia M, Lavie-Cambot A, McClenaghan ND, Credi A. A Ratiometric Luminescent Oxygen Sensor Based on a Chemically Functionalized Quantum Dot. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2011;47:325–327. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02163f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Fujiwara Y, Okura I, Miyashita T, Amao Y. Optical Oxygen Sensor Based on Fluorescence Change of Pyrene-1-butyric Acid Chemisorption Film on an Anodic Oxidation Aluminium Plate. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2002;471:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Vaugham WM, Weber G. Oxygen Quenching of Pyrenebutyric Acid Fluorescence in Water. A Dynamic Probe of Microenvironment. Biochemistry. 1970;9:464. doi: 10.1021/bi00805a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Snow TR, Jobsis FF. Characterization of Oxygen Probe Pyrenebutyric Acid in Rabbit Heart-Mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1976;440:36–44. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(76)90111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Takeuchi T, Kosuge M, Tadokoro A, Sugiura Y, Nishi M, Kawata M, Sakai N, Matile S, Futaki S. Direct and Rapid Cytosolic Delivery Using Cell-Penetrating Peptides Mediated by Pyrenebutyrate. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006;1:299–303. doi: 10.1021/cb600127m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Feng Y, Cheng J, Zhou L, Zhou X, Xiang H. Ratiometric Optical Oxygen Sensing: A Review in Respect of Material Design. Analyst. 2012;137:4885–4901. doi: 10.1039/c2an35907c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Lakowicz JR, Weber G. Quenching of Fluorescence by Oxygen. Probe for Structural Fluctuations in Macromolecules. Biochemistry. 1973;12:4161–4170. doi: 10.1021/bi00745a020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Rumsey WL, Vanderkooi JM, Wilson DF. Imaging of Phosphorescence - a Novel Method for Measuring Oxygen Distribution in Perfused Tissue. Science. 1988;241:1649–1651. doi: 10.1126/science.241.4873.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Ogilby PR. Singlet Oxygen: There Is Indeed Something New under the Sun. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:3181–3209. doi: 10.1039/b926014p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Krasnovsky AA. Photoluminescence of Singlet Oxygen in Pigment Solutions. Photochem. Photobiol. 1979;29:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lo LW, Koch CJ, Wilson DF. Calibration of Oxygen-Dependent Quenching of the Phosphorescence of Pd-Meso-Tetra (4-Carboxyphenyl) Porphine: A Phosphor with General Application for Measuring Oxygen Concentration in Biological Systems. Anal. Biochem. 1996;236:153–160. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Dunphy I, Vinogradov SA, Wilson DF. Oxyphor R2 and G2: Phosphors for Measuring Oxygen by Oxygen-Dependent Quenching of Phosphorescence. Anal. Biochem. 2002;310:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Schweitzer C, Schmidt R. Physical Mechanisms of Generation and Deactivation of Singlet Oxygen. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:1685–1757. doi: 10.1021/cr010371d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Ware WR. Oxygen Quenching of Fluorophores in Solution: An Experimental Study of the Diffusion Process. J. Phys. Chem. 1962;66:455–458. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Peterson JI, Fitzgerald RV, Buckhold DK. Fiber-Optic Probe for in Vivo Measurement of Oxygen Partial Pressure. Anal. Chem. 1984;56:62–67. doi: 10.1021/ac00265a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Trofymchuk K, Reisch A, Shulov I, Mely Y, Klymchenko AS. Tuning the Color and Photostability of Perylene Diimides inside Polymer Nanoparticles: Towards Biodegradable Substitutes of Quantum Dots. Nanoscale. 2014;6:12934–12942. doi: 10.1039/c4nr03718a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Brouwer AM. Standards for Photoluminescence Quantum Yield Measurements in Solution (IUPAC Technical Report) Pure Appl. Chem. 2011;83:2213–2228. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Rurack K, Spieles M. Fluorescence Quantum Yields of a Series of Red and near-Infrared Dyes Emitting at 600-1000 nm. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:1232–1242. doi: 10.1021/ac101329h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.