Abstract

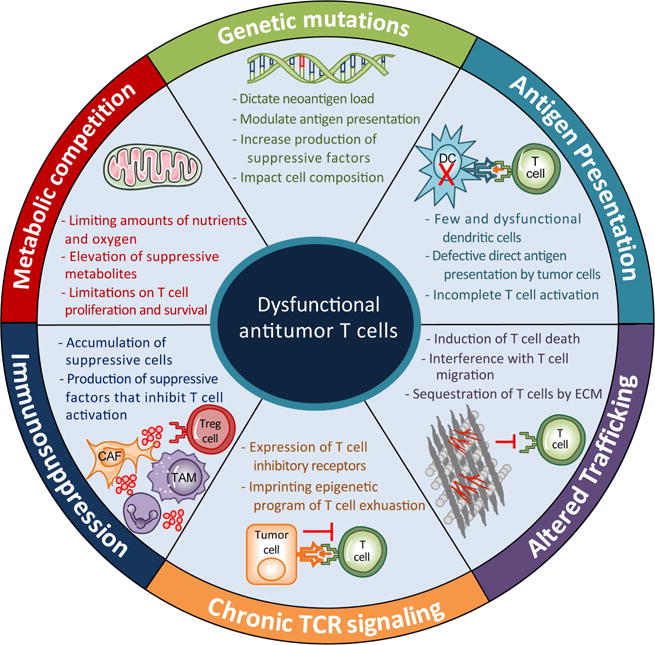

T cell dysfunction in solid tumors results from multiple mechanisms. Altered signaling pathways in tumor cells help produce a suppressive tumor microenvironment enriched for inhibitory cells, posing a major obstacle for cancer immunity. Metabolic constraints to cell function and survival shape tumor progression and immune cell function. In the face of persistent antigen, chronic T cell receptor signaling drives T lymphocytes to a functionally exhausted state. Here we discuss how the tumor and its microenvironment influences T cell trafficking and function with a focus on melanoma, pancreatic and ovarian cancer, and discuss how scientific advances may help overcome these hurdles.

Introduction

Solid tumors commonly arise from genetic mutations in driver oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that have profound consequences on cell differentiation, proliferation, survival and genomic stability. During cancer progression, tumor cells alter normal developmental processes to orchestrate a supportive but overtly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) comprised of immune cells, fibroblasts and endothelial cells, often embedded within a robust extracellular matrix (ECM) (Hanahan and Coussens, 2012; Stromnes et al., 2014b; Whiteside, 2008). From the formation of the earliest preinvasive lesion to metastatic spread, the TME can support angiogenesis, tumor progression, and immune evasion from T lymphocyte recognition, as well as dictate response to cancer therapy. Despite the significant obstacles that tumor-reactive T lymphocytes face in solid tumors, accumulating evidence indicates natural, induced, and engineered immune responses to cancer can dramatically change clinical outcomes, particular in certain malignancies (Chapuis et al., 2013; Galon et al., 2013; Kroemer et al., 2015; Rosenberg and Restifo, 2015; Turtle et al., 2016). Such clinical findings spark hope and excitement that a greater understanding of the relationship between the complex components of the TME and immune function will inform more broadly effective immunotherapies for intractable malignancies.

Immune checkpoint blockade (e.g., anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, or anti-CTLA-4), designed to amplify endogenous antitumor T cell responses, has revolutionized cancer treatment (Sharma and Allison, 2015). The success of this approach is notable in melanoma and non-small cell lung cancers that often contain numerous genetic mutations (Lawrence et al., 2013), a fraction of which produce neoantigens recognizable by endogenous T cells (Lu and Robbins, 2016; Stronen et al., 2016). The adoptive transfer of genetically engineered T cells to express a receptor specific for a tumor antigen is a more targeted approach and has shown efficacy in melanoma (Morgan et al., 2013) as well as tumors with lower mutational burdens. T lymphocytes engineered to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) specific to the B cell marker CD19 (Kalos et al., 2011; Turtle et al., 2016) or a T cell receptor (TCR) specific to self/tumor antigen Wilms’ tumor antigen (WT1) (Chapuis et al., 2013) have shown dramatic clinical responses in hematological malignancies. However, broadly translating similar approaches to treat carcinomas has proven more difficult. First, since reproducibly expressed candidate tumor antigens are also often self-antigens, toxicity can be limiting. Second, if tumors persist, chronic TCR signaling can lead to a T cell intrinsic program of exhaustion (Schietinger et al., 2016; Wherry et al., 2007). Thirdly, there are multiple immunosuppressive mechanisms operative in the TME that interfere with T cell function (Pitt et al., 2016). Additionally, even if tumor cell killing is transiently achieved, cancers can evade the immune system by a variety of mechanisms, including outgrowth of variants after immunoediting (Schreiber et al., 2011).

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) and high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC), which are often diagnosed at advanced stages, are largely resistant to therapy, including immune checkpoint blockade (Brahmer et al., 2012; Ring et al., 2016; Royal et al., 2010). These tumors have few coding mutations, and thus contain few neoantigens, as compared to melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer (Lawrence et al., 2013). Furthermore, while immune checkpoint blockade has yielded dramatic clinical responses particularly in the subset of malignancies with large mutational burdens (Hamid et al., 2013; Hodi et al., 2010), clinical responses are often not durable (Ribas et al., 2016), indicating that, even in highly responsive tumors, sustaining long-lasting immune activity is daunting. Thus, approaches that simultaneously promote T cell antitumor activity and avoid/overcome the most significant obstacle(s) in the relevant TME may prove most beneficial.

Tumor cell intrinsic genetic mutations can coordinate the induction of downstream and paracrine signaling pathways culminating in chronic fibroinflammatory states. These changes influence cell composition, ECM, vasculature, nutrient availability, bioenergetics and angiogenesis. Direct links between TME components and immune system suppression and evasion are increasingly being recognized (Pitt et al., 2016). Metabolic demands of both tumor cells and the supportive stromal network limit nutrient availability, and concurrently overexpose T cells to suppressive metabolites, thereby reducing T cell effector function (Chang and Pearce, 2016). Persistent antigen can cause chronic TCR signaling and T cell exhaustion, leading to epigenetic changes that may not be readily overcome by immune checkpoint blockade (Pauken et al., 2016; Sen et al., 2016). Finally, the heterogeneity of tumors not only between distinct malignancies, but also different individuals with the same type of cancer, or even tumor lesions in the same patient, complicates treatment strategies (Hugo et al., 2016; Makohon-Moore and Iacobuzio-Donahue, 2016; Schwarz et al., 2015). The design of successful immunotherapies must account for mutational and antigenic heterogeneity as well as TME complexity. The diverse array of immune evasion mechanisms employed by tumors highlights the necessity for combination and synergistic therapies. Here, we discuss major drivers of T cell dysfunction in the context of three solid tumors: 1) melanoma, in which T cell responses exist and frequently can be enhanced to mediate anti-tumor activity (Rosenberg and Restifo, 2015), 2) ovarian cancer, in which potentially beneficial T cell responses exist in a subset of patients, but have proven difficult to augment (Santoiemma and Powell, 2015) and 3) PDA, in which endogenous T cell responses are rare (Emmrich et al., 1998; Ene-Obong et al., 2013; von Bernstorff et al., 2001).

Tumor cell intrinsic pathways that modulate the TME and interfere with immunity

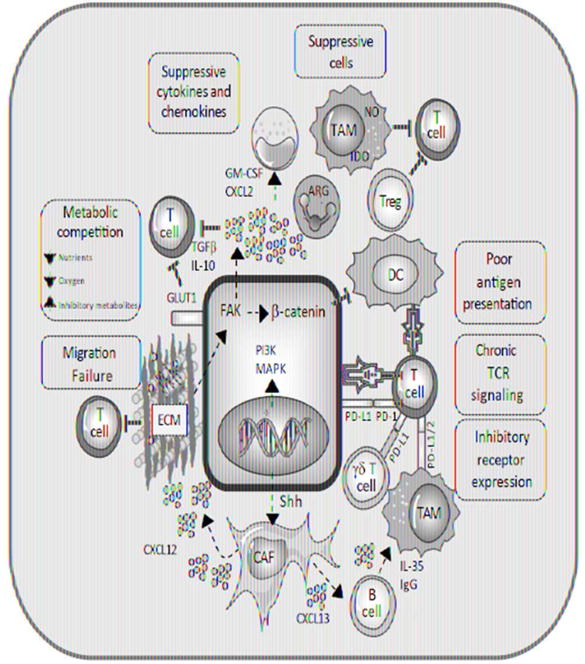

Pancreatic and ovarian cancer are each associated with several common oncogenic mutations that can influence the TME and immunity (Figure 1). Mutations in KRAS are common in both malignancies (Forbes et al., 2011) and play a critical role in the development of the TME. KrasG12D impacts all phases of tumor growth: initiation, invasion, maintenance and metastasis in PDA (Collins et al., 2012; Ying et al., 2012). KrasG12D increases tumor cell proliferation via MAPK and PI3K-mTOR signaling and modulates metabolism by glucose transporter GLUT1 upregulation (Ying et al., 2012). In addition to altering intrinsic tumor cell behavior, oncogenic Kras has pronounced indirect effects on neighboring cells. Introducing KrasG12D into normal mouse pancreatic ductal cells induces GM-CSF expression (Pylayeva-Gupta et al., 2012), and GM-CSF production recruits myeloid cells that interfere with CD8 T cell infiltration and tumor cell killing in PDA (Bayne et al., 2012; Pylayeva-Gupta et al., 2012). GM-CSF also recruits neutrophils to the TME, which facilitate PDA metastasis (Steele et al., 2016), and impair both T cell accumulation and priming in autochthonous PDA (Stromnes et al., 2014a). In addition to inducing downstream paracrine signaling to myeloid cells, KrasG12D increases Hedgehog ligands Shh and Ihh expression that activate αSMA+ cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) (Collins et al., 2012), leading to expansion of the fibroinflammatory stroma (Olive et al., 2009) and T lymphocyte exclusion (Feig et al., 2013; Lo et al., 2015). Finally, KrasG12D increases MMP7, COX2, IL-6 and pSTAT3 levels (Collins et al., 2012), thereby influencing innate cell signaling, chronic inflammation and ECM remodeling. Hence, a single oncogenic mutation can have profound effects on the development of the TME and the antitumor immune response. Although active Kras mutants are elusive therapeutic targets, a recent study using HLA-A*11:01 transgenic mice isolated TCRs reactive to KrasG12V7–16 and to KrasG12D7–16 neoepitopes but not wild type Kras (Wang et al., 2016), which could be useful tools for engineering T cells for the fraction of patients who are HLA-A*11:01+.

Figure 1.

Overview of obstacles in the tumor microenvironment that interfere with T cell trafficking and function.

Common pathways across distinct malignancies that may broadly influence cancer immunity are particularly intriguing. Oncogenic Kras or other signaling mechanisms can induce activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway (Lemieux et al., 2015). β-catenin is an integral E-cadherin adaptor protein and transcriptional co-regulator. β-catenin is commonly dysregulated in PDA (Zeng et al., 2006) and ovarian cancer (Bodnar et al., 2014), as a result of oncogenic signals or mutations in its gene (Zeng et al., 2006). β-catenin activation is detected in a subset of melanomas and is associated with a non-inflamed tumor gene signature and low T cell infiltration (Spranger et al., 2015). β-catenin signaling can indirectly prevent intratumoral T cell accumulation by inhibiting production of CCL4, a chemokine critical for recruitment of dendritic cells (DC), which prime naïve T cells and activate immune responses (Spranger et al., 2015). Substantial efforts are underway to target WNT/β-catenin signaling in cancer, including with newly designed small-molecule inhibitors (Zhang and Hao, 2015). Since these and many of the other small-molecule inhibitors being pursued target pathways also functional in hematopoietic cells, preclinical studies in autochthonous tumor models in which tumors arise in the native organ and the endogenous immune and hematopoietic systems are intact should prove helpful for predicting the potential for clinical success for such approaches.

Another neoplastic cell-intrinsic pathway impacting cancer immunity is focal adhesion kinase (FAK). FAK1 and PYK2/FAK2 are non-receptor tyrosine kinases that regulate adhesion, invasion, migration, proliferation and survival (Frame et al., 2010). FAK1 level is elevated in human PDA and correlates with robust fibrosis and poor CD8 T cell accumulation (Jiang et al., 2016). Tumor cell contact with rigid ECM components, such as collagen or fibronectin, induces Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase dependent activation of FAK1 (Jiang et al., 2016). Inhibiting FAK1 or FAK2 greatly reduces cytokine production, the frequencies of CAFs, suppressive myeloid subsets, and CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Treg), as well as ECM accumulation. FAK inhibition halts tumor growth and increases survival in a PDA mouse model, and anti-tumor activity can be further improved if combined with chemotherapy or anti-PD-1 (Jiang et al., 2016). FAK is implicated in suppression of antitumor immunity in other cancers as well. In squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), nuclear FAK associates with key transcription factors and induces CCL5 and TGFβ expression that recruit/induce tumor Treg (Serrels et al., 2015). Pharmacological FAK inhibition causes regression of autochthonous lung tumors in an oncogenic Kras driven model (Konstantinidou et al., 2013). FAK can interfere with TCR signaling in T cells (Chapman et al., 2013) suggesting FAK inhibition may have non-redundant effects by altering both tumor and immune cells. Furthermore, FAK signaling can induce nuclear localization of β-catenin and transcriptional activation of the β-catenin target gene MYC (Ridgway et al., 2012), suggesting a mechanistic link between these oncogenic pathways. A FAK inhibitor in combination with PD-1 blockade and gemcitabine is currently being evaluated in clinical trials for pancreatic and ovarian cancer (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02546531). Since T cell dysfunction in cancer is commonly restricted to the tumor site, investigation into how such combinations alter the TME and infiltrating T cells in patient biopsies will likely be critical for identifying reasons for therapeutic failure and/or success.

Mutations in the tumor suppressor geneTP53, which occur in many solid tumors, are also associated with a suppressive TME. TP53 is mutated in approximately 96% of high-grade serous ovarian cancers (TCGA Research Network, 2011), 75% of PDAs (Rozenblum et al., 1997), and 19% of melanomas (Hodis et al., 2012). In normal cells, p53 is activated upon cell stress to induce cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, cell senescence, and/or apoptosis. Thus, p53 loss can promote tumorigenesis by disrupting normal cell cycle checkpoints. Several missense p53 mutants exert further oncogenic effects by promoting tumor growth, metastasis and modulating a more suppressive TME (Rivlin et al., 2011). p53 loss can induce overexpression of CCL2, which recruits suppressive myeloid cells into the TME (Walton et al., 2016). Mutant p53 can disrupt TGFβ signaling and promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastatic invasion (Elston and Inman, 2012). An EMT gene signature is associated with resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma and a similar EMT gene signature is prominent in PDA (Hugo et al., 2016), underscoring potentially key immunosuppressive events linked with EMT in solid tumors.

T cell exclusion from solid tumors

Solid tumors can facilitate immune evasion by restricting T cell migration. Indeed, many solid tumors are classified based on the T cell infiltrate; the presence of T cell-infiltration contributes to a higher “immunoscore” that correlates with improved patient prognosis (Curiel et al., 2004; Galon et al., 2006). Several key events in lymphocyte migration contribute to T cell infiltration including: 1) selectin-mediated rolling, 2) chemokine-mediated integrin activation, 3) integrin-mediated arrest, and 4) extravasation across the endothelial barrier (Schenkel and Masopust, 2014). Although many tumors over-express VEGF, and rapidly growing lesions often develop hypoxic regions that stimulate angiogenic growth, the tumor neovasculature is abnormal relative to traditional blood vessel architecture (Nagy et al., 2009), which can disrupt events essential to lymphocyte infiltration. Tumor vasculature also often exhibits irregular distribution, branching, and blood flow, leading to dysregulation of T cell trafficking, and formation of regions within the TME with varying perfusion and oxygen levels. This heterogeneity in nutrient and oxygen availability across spatial regions further influences T cell entry, function and survival.

Tumor cells can modulate the adhesion and chemotactic signals in the vasculature to promote recruitment of suppressive cells and exclude anti-tumor T cells. Some tumors downregulate expression of adhesion molecules ICAM-1/2, VCAM-1 and CD34 on tumor endothelium (Slaney et al., 2014), interrupting an essential step in T cell trafficking. In ovarian cancer, upregulation of endothelin B receptor (ETBR) on tumor vasculature suppresses T cell infiltration by preventing clustering of ICAM-1 on endothelial cells (Buckanovich et al., 2008), which is required for T cell arrest and extravasation. ETBR expression on tumor vasculature is correlated with reduced T cell infiltration and poor prognosis in several tumors (Tanaka et al., 2014). Further, since activated T cells often use CXCR3 to migrate preferentially to inflammatory sites that abundantly express CXCL9, CXCL10 and/or CXCL11, intratumoral elevation of these chemokines correlates with enhanced T cell infiltration (Guirnalda et al., 2013). However, not all tumors express sufficient CXCR3 ligands to recruit T cells (Harlin et al., 2009; Mulligan et al., 2013) and epigenetic silencing of T cell attracting chemokines in ovarian cancer has recently been shown to be another mechanism of immune evasion (Peng et al., 2015). Pro-inflammatory chemokines present in the TME can also be altered to prevent T cell infiltration. Suppressive myeloid cells often produce reactive oxygen species that nitrate and disable CCL2, preventing T cell infiltration beyond the tumor stroma (Molon et al., 2011). Finally, expression of FasL, which induces apoptotic death of cells expressing the Fas receptor (Fas), has been demonstrated on the tumor vasculature in ovarian cancer and other tumor types, and reduces T cell infiltration (Motz et al., 2014). In PDA, FasL is additionally expressed by tumor cells, suggesting Fas-dependent induction of effector T cell death can be utilized by multiple cell types in the TME (Bernstorff et al., 2002; Pernick et al., 2002).

The desmoplastic fibroinflammatory response characteristic of PDA may influence T cell infiltration. CAFs secrete ECM components that physically trap T cells within stroma and prevent T cells from migrating toward dens tumor cell regions. Excessive collagen deposition may be a barrier to T cell entry, as ex vivo models have demonstrated that collagen degradation increases T cell infiltration (Salmon and Donnadieu, 2012). Further, CAFs secrete CXCL12, which can coat cancer cells and prevent T cell infiltration and tumor lysis (Feig et al., 2013). In our studies of TCR-engineered effector CD8 T cells, infused T cells readily infiltrated autochthonous PDA and preferentially accumulated in the tumor sites (Stromnes et al., 2015), suggesting that cellular engineering and ex vivo activation may provide a means to improve T cell migration and infiltration of solid tumors.

Tumor microenvironment factors that regulate T cell anti-cancer activity

As pre-invasive tumor lesions develop, a variety of cell types are recruited to the TME that dampen antitumor immunity. The TME is highly complex and comprised of diverse populations of CAFs, endothelial cells, myeloid cells, suppressive B cells, Tregs and γδ T cells. These immunosuppressive cells types have been reviewed elsewhere (Becker et al., 2013; Hanahan and Coussens, 2012; Kumar et al., 2016; Stromnes et al., 2014b; Whiteside, 2008) and thus will be only briefly summarized here.

The heterogeneous cells types within the TME contribute to T cell suppression through both direct contact and secretion of soluble factors. Stromal cells can limit T cell trafficking within the TME (as discussed above), promote Treg development and inhibit T cell proliferation (Haddad and Saldanha-Araujo, 2014). Also, as discussed, endothelial cells can directly prevent T cell trafficking into the TME, and can induce T cell apoptosis. Myeloid subsets including tumor-associated macrophages (TAM), granulocytes and inflammatory monocytes can be actively recruited to the TME and mediate suppression (Stromnes et al., 2014c). Macrophages in tumors characteristically adopt an anti-inflammatory phenotype with reduced MHC expression and elevation of inhibitory ligands such as PD-L1. Furthermore, myeloid cells are influenced by factors within the TME to differentiate into cells producing anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-10 and TGFβ. Regulatory B cells interfere with antitumor T cell immunity by promoting Treg development, secreting suppressive cytokines such as IL-10, and stimulating suppressive myeloid cells (Gunderson et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2016; Pylayeva-Gupta et al., 2016; Schwartz et al., 2016). γδ T cells can exhibit both pro- and anti-tumor activity, with suppressiveγδ T cells producing IL-10 and TGFβ (Wesch et al., 2014). TGFβ is highly suppressive to T cells, and engineering T cells to be refractory to TGFβ signaling can at least transiently enhance effector T cell accumulation and function in tumors (Chou et al., 2012). Many of the immunosuppressive subsets including γδ T cells can express inhibitory ligands, such as PD-L1, which interferes with the antitumor activity of T cells expressing the PD-1 receptor (Daley et al., 2016). γδ T cells are not antigen-presenting cells and thus not likely to present antigen to T cells, suggesting inhibition via PD-L1 expression on γδ T cells and potentially other TME cells is occurring in trans. There is not a particular hierarchy to immunosuppression in solid tumors, and the dynamic nature and potential redundancy of suppressive mechanisms suggests targeting a single molecule or suppressive cell subset may only provide an incremental advance in patients. Combining nanoparticles that deliver cytotoxic drugs capable of inducing immunogenic tumor cell death with checkpoint blockade (He et al., 2016), or modulating intratumoral innate immunity (Corrales et al., 2017), shows promise in preclinical models. Such approaches may be particularly beneficial if the tumor contains multiple neoantigens for the endogenous immune response to recognize. Combining similar approaches with transfer of engineered T cells should be further evaluated for safety and activity in cancers in which there are fewer mutations and less likelihood for the endogenous immune response to have activity. Studies are needed to investigate the impact of depleting (or converting the function of) multiple suppressive cell types in tandem to acquire insights about the distinct and overlapping activities of immunosuppressive cells and potential for toxicity. Engineering T cells to evade suppressive signals from the TME may prove to be a more efficient way to overcome these hurdles with less risk of systemic toxicity from globally altering immunosuppression.

Metabolic challenges in the TME: impact on T lymphocytes and immunity

The desmoplastic response characteristic of solid tumors can create areas of hypoxia and necrosis with limited nutrient availability, which imposes considerable bioenergetic constraints on both tumor cells and immune cells. Sugars, amino acids and fatty acids are major fuel sources utilized by eukaryotic cells, but proliferating tumor cells rapidly deplete these nutrients, subjecting both tumor and immune cells to a nutrient poor TME. Tumor cells can use adaptive mechanisms to survive these harsh conditions including increasing expression of nutrient import molecules or utilizing metabolic byproducts as alternative fuel sources. Hence, tumor cells can undergo a dynamic metabolic reprogramming that confers cell plasticity and survival in such harsh conditions while concomitantly further depriving immune cells of nutrients essential for their function and survival. Both cell intrinsic events, such as driver mutations, and paracrine signaling from surrounding stroma can contribute to tumor cell metabolic reprogramming and flexibility. The consequences of metabolic re-wiring at cancer sites are not restricted to tumor cells; these changes have protean effects on tumor-stromal interactions, the TME and cancer immunity (Figure 2).

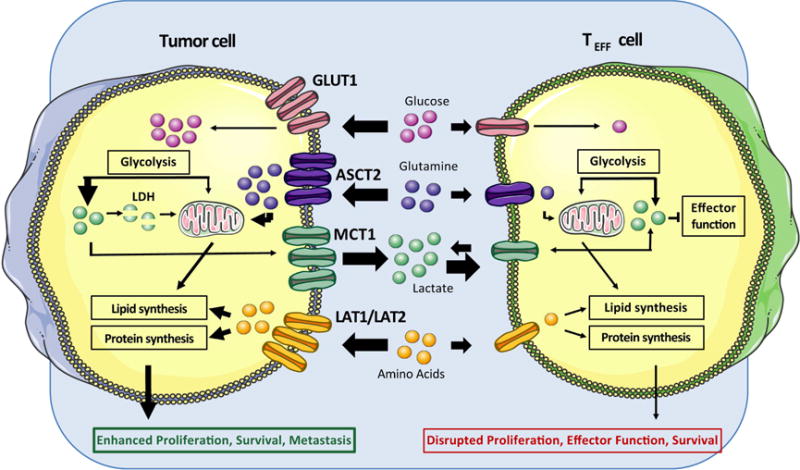

Figure 2.

Metabolic perturbations within tumor cells modulate the tumor microenvironment to limit nutrient availability and generate metabolic byproducts that suppress T cell function.

Glucose

One predominant fuel source for rapidly dividing cells is glucose. Glucose metabolism for rapid energy production even in the presence of oxygen is a hallmark of malignant transformation (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011; Ward and Thompson, 2012) and a potential target for cancer therapy (DeBerardinis and Chandel, 2016). The metabolic switch from cellular respiration to aerobic glycolysis is known as the Warburg effect (Warburg et al., 1927). As all rapidly dividing mammalian cells require high glucose uptake to sustain proliferation, tumor cells, stromal cells and immune cells must compete for this vital but limited nutrient. To satisfy the demand, both tumor cells and activated T cells increase expression of the receptor for glucose internalization, glucose transporter GLUT1 (Carvalho et al., 2011; Wofford et al., 2008; Ying et al., 2012). In tumors, oncogenic signaling and hypoxia can drive the expression of glucose metabolism genes (Cohen et al., 2015). As tumor cells can express more nutrient import molecules than activated T cells, tumor cells commonly outcompete immune cells for glucose. Indeed, overexpression of GLUT1 in cancer cells correlates with low CD8 T cell infiltration in renal cell carcinoma (Singer et al., 2011) and SCC (Ottensmeier et al., 2016), and poor patient prognosis in melanoma (Su et al., 2016), PDA (Davis-Yadley et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2016) and ovarian cancer (Cho et al., 2013). Successful competition for glucose by tumor cells facilitates the capacities to simultaneously maintain high metabolic and proliferative rates while suppressing anti-tumor immunity. Notably, signaling via PD-1 expressed by melanoma cells enhances aerobic glycolysis in a tumor-cell intrinsic, mTOR-dependent manner, suggesting the activity of immune checkpoint blockade may be due in part to altering tumor glucose metabolism (Kleffel et al., 2015).

Effector T cells, similar to tumor cells, also need to undergo a metabolic switch to the glycolytic pathway to support rapid growth and production of effector molecules. In the TME, glucose availability is limited, and effector T cells exposed to restricted glucose levels have significantly reduced anti-tumor activity (Chang et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2015). Insufficient levels of glucose and other nutrients directly reduce T cell proliferation (Jacobs et al., 2008; Renner et al., 2015), cytokine production (Cham et al., 2008; Ota et al., 2016) and TCR signaling (Ho et al., 2015). During chronic viral infection, exhausted CD8 T cells have greatly reduced expression of genes involved in glycolysis (Wherry et al., 2007), and deficient glucose metabolism and T cell dysfunction have been linked (Bengsch et al., 2016). Thus, extrinsic metabolic pressure on CD8 T cells may contribute to dysfunction independent of inhibitory receptor ligation. Notably, suppressive Treg are not as dependent on glycolysis but rather rely on oxidative mitochondrial pathways for energy production (Michalek et al., 2011), which may contribute to the abundance of functional Treg in solid tumors (Curiel et al., 2004). Since naïve T cells and resting memory T cells predominantly utilize oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) (Buck et al., 2015; Pearce et al., 2009), it may be possible to engineer effector T cells to better utilize such pathways to sustain function in the TME.

Amino Acids

Tumor cells and T cells are not strictly dependent on glucose for cellular metabolism; amino acids, acetate and fatty acids can be metabolized for macromolecule production, and tumor cells rely heavily on these pathways when glucose is limited, which again may interfere with availability for immune cells. In melanoma, PDA, and ovarian cancer glutamine addiction is common (Fan et al., 2013; Filipp et al., 2012; Hensley et al., 2013; Son et al., 2013). Amino acid transporters (ASCT2 and LAT1) are overexpressed in melanoma (Wang et al., 2014), pancreatic cancer (Kaira et al., 2012) and ovarian cancer (Kaira et al., 2015) and correlate with poor prognosis. This flexible tumor cell metabolic profile can further impact the milieu of the TME. In patients with ovarian cancer, tumor cells can for their benefit alter neighboring stromal cell metabolism. Ovarian tumors that thrive on glutamine develop a feedback loop with CAFs whereby tumor cells metabolize glutamine, produce the metabolic byproducts glutamate and lactate, and CAFs then metabolize these back to glutamine (Yang et al., 2016), which is degraded by the tumor cells via a metabolic pathway not utilized by stromal cells found in normal ovary tissue. Pancreatic cancer cells can similarly use adipocyte-derived glutamine to promote cell proliferation (Meyer et al., 2016). In vitro, activated T cells can use increased amounts of glutamine as a metabolic substrate, and exhibit reduced proliferative capacity and cytokine secretion when glutamine concentrations are low (Carr et al., 2010). Thus, decreased glutamine availability would be expected to also hinder immune responses in situ.

L-arginine is another amino acid known to play a critical role in antitumor T cell immunity that is often depleted in tumors. The enzymes nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and arginase (ARG) are critical for L-arginine metabolism, and many solid tumors, including melanoma and ovarian cancer, overexpress one or both of these enzymes (Mocellin et al., 2007). The oxidation of arginine by NOS produces nitric oxide (NO), which can interact with reactive oxygen species to generate reactive nitrogen species that are toxic for intratumoral T cells (Mocellin et al., 2007). However, local NO production by intratumoral DC can alternatively promote tumor destruction by adoptively transferred CD8 cytotoxic T cells (Marigo et al., 2016), indicating NO can have pro- or anti-tumor activity. High levels of ARG in tumor cells correlate with an increase in suppressive TAMs (Tham et al., 2014). The presence of arginine during T cell activation promotes T cell effector function and survival and memory T cell differentiation (Geiger et al., 2016), suggesting arginine deficits within the TME may also contribute to T cell dysfunction. Thus, manipulation of NOS and ARG activity in tumor sites may enhance the efficacy of T cell therapies.

Fatty Acids

Dividing cells require fatty acids (FA) to form new cell membrane lipid bilayers (O’Flanagan et al., 2015). Thus, it is not surprising that neoplasms also utilize free FA and lipogenesis following malignant transformation. In addition to supporting cellular growth, free FA are used by many cells as an energy source. Fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) is a process by which eukaryotic cells convert free fatty acids to acetyl-CoA for mitochondria-driven energy production. Tumor cells with enhanced FAO can sustain growth and continue to produce energy when other nutrients are limited. In extreme conditions, tumor cells can even induce metabolic alterations in neighboring cells to support their own growth. For example, ovarian cancer cells can alter the metabolism of neighboring adipocytes to catabolic processes that release free FA, which the tumor cells then utilize to support proliferation (Nieman et al., 2011).

Tumors with increased reliance on FA generally increase expression of fatty acid synthase (FAS), an enzyme responsible for fatty acid elongation during lipogenesis, allowing tumor cells to readily generate fatty acids if other nutrient levels are replete. Melanoma, prostate, breast, pancreatic and ovarian tumors that overexpress FAS have a worse prognosis (Bian et al., 2015; Epstein et al., 1995; Gansler et al., 1997; Innocenzi et al., 2003; Rosolen et al., 2016; Ueda et al., 2010; Witkiewicz et al., 2008b). This enhanced transition between FA generation when nutrients are abundant and FA metabolism when nutrients are limited may provide tumor cells with a survival advantage over cells with less metabolic flexibility, like antitumor effector T cells. Inhibition of FAS with biochemical inhibitors in vitro results in pancreatic cancer cell death (Nishi et al., 2016), suggesting this metabolic pathway may be critical for tumor cell survival and that chemical inhibitors targeted to metabolic processes uniquely accessed by tumor cells have the potential to improve antitumor therapy.

While effector T cells do not rely heavily on FAO to mediate effector functions, memory T cells do not develop if FAs are absent (Pearce et al., 2009), and formation of such long-lived antitumor T cells that retain function and proliferative capacity may be important for sustaining productive tumor immunity. Promoting mitochondria-driven metabolism through the engineered expression of PCG1α not only increases mitochondrial function, but bolsters T cell effector function and tumor control in a murine melanoma model (Scharping et al., 2016). This suggests that strategies to modify T cell bioenergetics and promote the use of oxidative metabolic pathways may improve the efficacy of T cell therapies.

Lactate and extracellular acidification

One consequence of high rates of aerobic glycolysis is enhanced production of lactate with associated increased acidity in the TME. While this presents an obstacle for immune cells, tumor cells can often adapt to survive and proliferate despite these harsh conditions. Tumor cells can respond to extracellular acidosis and maintain redox balance by altering expression of pH-regulating proteins, such as monocarboxylate transporters (MCT) and carbonic anhydrases (Parks et al., 2013). Numerous cell types within tumors produce lactate, which can promote tumor growth and metastasis in a variety of ways. In an in vitro model of melanoma, lactate exposure is associated with an increased EMT phenotype (Peppicelli et al., 2016). In a xenograft model of glioblastoma, lactate induces VEGF expression that promotes angiogenesis (Talasila et al., 2016). In pancreatic and ovarian cancer cell cultures, lactate promotes IL-8 production, leading to EMT and metastasis (Shi et al., 1999; Shi et al., 2000; Xu and Fidler, 2000), and the tumor cells can use the lactate as an alternate fuel source, promoting cell proliferation (Guillaumond et al., 2013). Indeed, high levels of lactate in PDA are associated with poor prognosis (Cohen et al., 2015). Tumor-derived high lactate concentrations block needed export of intracellular lactate by T cells in vitro (Fischer et al., 2007), and excess extracellular lactate also results in disruption of aerobic glycolysis with decreased production of IFNγ by T cells and NK cells (Brand et al., 2016; Pilon-Thomas et al., 2016). The presence of excess lactate can also enhance the functions of immunosuppressive cells, such as myeloid subsets, and polarize macrophages to an immunosuppressive phenotype (Colegio et al., 2014; Husain et al., 2013). Developing approaches to modify T cells to use lactate as an energy and biomolecule source, similar to pathways operative in some tumor cells, may provide means to overcome this hurdle for tumor immunity.

IDO and suppressive metabolites

Indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is an immunoregulatory enzyme that converts tryptophan into metabolic byproducts known as kynurenines (Grohmann et al., 2003). High levels of IDO have been reported in melanoma (Brody et al., 2009), PDA (Witkiewicz et al., 2009) and ovarian cancer (Inaba et al., 2009) as well as many other tumors (Wainwright et al., 2012). IDO is associated with reduced CD8 T cell infiltration and poor patient survival (Pelak et al., 2015; Speeckaert et al., 2012). IDO promotes peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer cells by promoting angiogenesis and generating a tolerogenic environment that suppresses anti-tumor immune responses by NK cells and T cells (Tanizaki et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2012). IDO can recruit Tregs to the TME (Holmgaard et al., 2015; Nakamura et al., 2007; Witkiewicz et al., 2008a) and indirectly promote suppressive myeloid cells (Smith et al., 2012), and the associated tryptophan depletion and consequent metabolic byproducts directly suppress anti-tumor T cell responses (Munn and Bronte, 2016; Platten et al., 2014). The diminished tryptophan concentration in the TME prevents T cell proliferation (Mellor et al., 2004), and, in some cases, the kynurenine byproducts can interfere with TCR signaling by downregulating CD3ζ expression or can induce T cell death (Grohmann et al., 2003).

It is likely that many other metabolic alterations in the TME influence anti-tumor immunity. Necrosis in the TME results in increased concentrations of potassium, which suppresses T cell function in a mouse melanoma model (Eil et al., 2016). As necrosis is pervasive in PDA (Seifert et al., 2016) and many other tumors, this mechanism may more generally operate in tumors to inhibit T cells. Further investigation of immunosuppressive pathways related to tumor necrosis may reveal additional obstacles to T cell function that should be addressed.

Hypoxia

As solid tumors progress, large areas often become deprived of oxygen, which can interfere with immunity. Some tumors respond by overexpressing VEGF, which stimulates angiogenesis, but the induced neovasculature is often abnormal and fails to adequately improve oxygen perfusion throughout the tumor. Even if vessels have normal distribution, the robust desmoplasia, such as in PDA, may collapse vessels and interfere with perfusion, promoting maintenance of a hypoxic TME (Koong et al., 2000; Olive et al., 2009). The regions of low oxygen concentration induce expression of the transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) in tumor cells. HIF-1α in turn promotes expression of genes that drive angiogenesis, genetic instability, EMT and glycolysis (MacIver et al., 2013), supporting tumor cell growth and invasion. Together, these processes result in heterogeneous tumor masses that include regions with low concentrations of molecules critical for immune cell growth and survival.

The lack of oxygen in the TME can suppress anti-tumor immunity and promote tumor evasion. However, the impact hypoxia has on T cells depends on the differentiation state of the cells. For instance, while naïve and memory T cells exhibit reduced proliferative capacity, effector function and viability when oxygen is limited (Kim et al., 2008), the opposite is true for differentiated effector T cells (Xu et al., 2016). Since HIF-1α activation in T cells promotes glycolysis, the predominant metabolic program utilized by activated T cells, slightly hypoxic regions may promote metabolic programs that increase the ability of T cells to compete for nutrients. While this mechanism could facilitate antigen clearance in slightly hypoxic environments, such as non-lymphoid tissues during acute infection, the forced increased dependence on glycolysis when glucose is limited may push T cells to dysfunction rapidly within tumors.

Much of our current understanding of tumor and T cell metabolic pathways relies on experiments performed with cell lines or cells isolated from tumors and examined in vitro, and the extent to which these mechanisms occur in situ remains to be confirmed. However, cancer metabolic plasticity and heterogeneity likely has implications for developing effective metabolic therapies. Since tumor cells can often utilize a variety of nutrients as fuel sources, targeting a single pathway may have limited activity. Despite these challenges, a variety of metabolic-modulating agents are in clinical development for treatment of cancer (Cohen et al., 2015). Careful consideration should be given if these agents are being combined with immunotherapy, as metabolic processes within immune cells may also be disrupted, thereby precluding immune anti-tumor effects.

Chronic TCR signaling can enhance T cell dysfunction in solid tumors

During a productive immune response, naïve T cells (TN) rapidly differentiate into effector T cells (TEFF) with unique metabolic, functional and migratory properties that promote cellular proliferation and infiltration into peripheral tissues. Following antigen recognition, TEFF rapidly express cytokines and lytic molecules that mediate specific killing of infected or transformed cells. While the vast majority of TEFF undergo cell death following antigen clearance, a minor fraction differentiate into long-lived memory T cells that can rapidly respond to if antigen is again encountered (Kaech and Cui, 2012). In contrast, during chronic viral infection and in the setting of many progressing tumors, the functional capacity of antigen-specific T cells becomes compromised (Baitsch et al., 2011; Giordano et al., 2015; Schietinger et al., 2016; Stromnes et al., 2015; Wherry et al., 2003; Wherry et al., 2007). Fundamental principles of acquired T cell dysfunction during chronic antigen stimulation have been obtained from studying chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection in mice in which T cells progressively lose the ability to proliferate, produce cytokines, and lyse target cells (Wherry et al., 2003). This acquired dysfunction, or exhaustion, is associated with co-expression of a variety of inhibitory receptors such as PD-1, Tim-3, CD244 and Lag3 (Blackburn et al., 2009; Wherry and Kurachi, 2015).

To develop a T cell therapy platform for targeting solid tumors such as pancreatic, ovarian and lung cancer, we engineered mouse T cells to express a TCR specific for the self/tumor antigen mesothelin. TCR-engineered T cells adoptively transferred into a genetically engineered autochthonous mouse model of PDA surprisingly readily infiltrated primary tumors and metastases and had significant anti-tumor activity (Stromnes et al., 2015). Over time, however, the TCR-engineered effector T cells that had infiltrated tumors progressively lost the abilities to produce IFNγ, TNFα and degranulate, whereas transferred T cells isolated from the spleens of the same recipients remained functional (Stromnes et al., 2015). T cells infiltrating melanoma in an engineered mouse model showed a similar dysfunctional phenotype (e.g., loss of cytokine production) restricted to cells localized in the TME, which in part reflected inhibitory cytokines elevated in the tumor site (Giordano et al., 2015).

Naive T cells that first encounter a model neoantigen in developing liver tumors also rapidly became dysfunctional as a consequence of continual antigen recognition/TCR signaling rather than extrinsic suppressive aspects of the hepatic tumor microenvironment (Schietinger et al., 2016). Notably, no detectable T cells persisting in tumors could produce cytokines and ultimately these T cells became refractory to PD-1 blockade, acquiring an epigenetic program of exhaustion imprinted from chronic TCR signaling. Thus, driver mutations may render T cells specific for this subset of attractive neo-antigens dysfunctional from unabated chronic TCR signaling during tumor development, and thereby preclude the therapeutic utility of checkpoint blockade or vaccines designed to activate such T cells. In sum, both naïve tumor-specific T cells as well as engineered effector tumor-reactive T cells are susceptible to acquiring an epigenetic program of exhaustion, similar to recent studies examining chronic viral infection (Pauken et al., 2016; Sen et al., 2016). Differences between mouse and human enhancer elements in the PD-1 locus in T cells have been identified (Sen et al., 2016), highlighting the need for caution evaluating the application to human studies of strategies rescuing T cell exhaustion in mouse models.

Many pathways engaged in chronically stimulated and dysfunctional T cells are also enriched in functional T cells following TCR signaling. Inhibitory receptors such as PD-1, TIGIT, CTLA-4, and Tim-3 frequently associated with functional impairment are also transiently upregulated in functional T cells following TCR signaling (Legat et al., 2013; Stromnes et al., 2015), suggesting a role in physiologic responses. However, tumor-specific T cells isolated from tumors often express distinctly high levels of these inhibitory receptors long after initial antigen exposure, presumably due to chronic TCR signaling from abundant persisting tumor antigens. The search for a gene signature associated with dysfunction distinct from T cell activation suggested that metallothioneins, which regulate intracellular Zn2+ levels, and the downstream zinc-finger transcription factor, GATA-3, may selectively promote T cell dysfunction in a mouse melanoma model (Singer et al., 2016). Single cell sequencing revealed that PD-1+Tim3+ tumor-infiltrating metallothionein-deficient T cells were functional despite co-expression of PD-1 and Tim3, suggesting potential intracellular targets for disrupting the dysfunctional pathway. These results suggest further studies in informative models may reveal additional targetable pathways by which cells, factors, and inhibitory signals within the TME cause T cell dysfunction.

Final thoughts: Emerging strategies to overcome obstacles posed by the TME and promote antitumor immunity

Despite some dramatic successes, reproducibly promoting and maintaining immune-mediated anti-tumor activity in solid tumors remains a formidable task, reflecting not only the capacity of many tumors to exclude T cells but also the myriad suppressive factors potentially operative at the tumor site and the induction of T cell intrinsic dysfunction once T cells have entered the TME (Figure 3). Moreover, the critical obstacle(s) posed by the TME that limit the efficacy of immune therapies will likely vary with, and need to be tailored to, the tumor type. Thus, it will be essential to elucidate the relevant immunosuppressive pathways both by using animal models that faithfully recapitulate the hallmark features of a particular human cancer, including autochthonous tumor models, and by analyzing human tumor tissues to guide selection of relevant strategies for manipulating the TME. However, selection of the model system(s) will need to be based on the questions being investigated, and preclinical findings further validated by patient sample analysis.

Figure 3.

Drivers of T cell dysfunction in tumors.

While pre-clinical models provide a valuable opportunity to evaluate the effect of manipulating TME components, thorough evaluation of the advantages and limitations of each model type remains critical. Implantable syngeneic tumor cell lines offer ease of study and can be readily genetically altered in vitro prior to implantation. For example, introducing genetic alterations can render tumor cells more similar to human cancer (Walton et al., 2016). Syngeneic tumors can then be evaluated in immunocompetent hosts, making it feasible to identify and manipulate TME immunosuppressive pathways. Additionally, the safety of therapeutic strategies with the potential for off-tumor pathologies can be assessed. However, if not implanted orthotopically, different environmental cues may alter the growth pattern, immune infiltration, and immunosuppressive features in a manner dissimilar to human cancer. Furthermore, even orthotopic models often fail to develop the stromal elements and/or heterogeneity observed in human tumors. Thus, studies of immunotherapeutic approaches in implantable syngeneic models or xenografts should be evaluated with caution. In PDA, this is particularly critical as the dense stromal response in autochthonous tumors creates a biophysical barrier to drug penetration that does not occur in implantable systems (Provenzano et al., 2012). Autochthonous models may more accurately recapitulate the histopathology and dissemination of human cancer, but fail to mimic the genetic heterogeneity or neoantigenicity observed in human tumors. Xenograft models offer an opportunity to examine anti-tumor activity in vivo with human-specific reagents, and transplantation of human tumor organoids may more accurately recapitulate the stromal response of human cancer than implanted human tumor cell lines (Boj et al., 2015). However, due to the immunocompromised nature of the host and the differences between mouse and human cellular components and protein orthologs, manipulation of TME immunosuppressive pathways as well as off-tumor toxicities can rarely be adequately evaluated. Humanized mouse models geared to provide greater human immune system components in immunocompromised mouse strains may create a more representative immunologic milieu for tumors growing in xenograft models (Rongvaux et al., 2014). However, the immune repertoire and function is currently still quite limited and will benefit from further development. Additionally, distinctions between the human and mouse immune systems have also been described that may reflect, in part, the housing of most laboratory mice in specific pathogen free conditions (Zschaler et al., 2014). Co-housing inbred mice with mice exposed to microbes during development may render inbred mouse immune systems more similar to adult human immune systems (Beura et al., 2016). Since the microbiome can impact cancer immunosurveillance and therapy (Zitvogel et al., 2016), future studies that utilize mice housed in more representative environments may provide avenues of investigation that could lead to novel types of cancer therapies.

Careful thought must also be given to whether to use systemic or locally delivered treatment approaches, as these have distinct advantages/disadvantages but may yield different outcomes. For example, metabolic and epigenetic inhibitors given systemically may slow tumor growth, increase expression of neoantigens, enhance immunogenic antigen presentation, and/or promote a favorable TME for anti-tumor T cell function, but the effects on other tissues and components of the immune response may also negatively influence anti-tumor immunity. More targeted approaches, such as by delivery to tumor sites via direct injection or nanoparticles, are attractive, as they are likely to yield fewer non-specific and unanticipated effects, but currently have the limitation that most of these delivery approaches will fail to reach all tumor cells, resulting in outgrowth of variants not modified by the therapy.

Another avenue with significant potential is T cell engineering. Great success has already been observed in patients who have received T cells engineered to express an antigen receptor that targets hematologic malignancies (Chapuis et al., 2013; Kalos et al., 2011; Turtle et al., 2016). However, these approaches have thus far yielded only modest therapeutic efficacy in solid tumors (Beatty et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2016; Kershaw et al., 2006; Louis et al., 2011), which may be due in part to the immunosuppressive TME. Once safety is established with CAR or TCR engineered cells, further engineering may afford unique opportunities to modify multiple qualities of anti-tumor T cells outside of the body and return the cells with an enhanced ability to survive and function within the TME. For example, rather than treating patients with both engineered T cells and checkpoint inhibitors to sustain T cell activity, with the latter impacting endogenous T cells throughout the body as well, it is possible to engineer T cells with both an anti-tumor receptor and altered inhibitory receptor expression simultaneously. This approach may preclude the need for systemic checkpoint blockade by targeting immune-enhancement specifically to the engineered therapeutic T cells, which could greatly reduce toxicity. Migratory, costimulatory, epigenetic, and metabolic pathways are also amenable to engineering in vitro, allowing for the generation of anti-tumor T cells with functional and survival advantages compared to their endogenous counterparts. Newer engineering strategies (e.g. gene editing with CRISPR, delivery of genes in vivo with nanoparticles, etc.) are under development and will need to be evaluated in faithful models of human cancer.

Ultimately, the broad array of immunosuppressive and inhibitory obstacles within the TME may prevent single agent therapies from yielding more than modest improvements. Thus, studies that focus on the effects of TME interventions in combinations may have the greatest potential to yield productive benefit. The nature of successful therapeutic interventions will likely differ for strategies involving engineered cells and those that target the endogenous immune response, and for some tumors it may be critical to pursue both strategies simultaneously. Targeting multiple key molecules and cells that have major roles in stromal formation and in immunosuppression may be essential for eliciting/maintaining immune responses and achieving clinical responses in currently recalcitrant cancers. Many strategies to deplete or modify immunosuppressive cells in tumors are currently under evaluation, but, with the multitude of immunosuppressive cells potentially operative that contribute to T cell inhibition, depletion of all of these subsets will be difficult and thus combinatorial depletion efforts must be pursued rationally based on preclinical data. Strategies that modify engineered T cells to evade suppressive signals from the TME may alternatively provide opportunities to circumvent suppressive pathways without global systemic depletion of cell subsets or administration of blocking monoclonal antibodies. Chimeric receptors that convert a negative signal from an inhibitory receptor, such as PD-1, into an activating signal by swapping the signaling cytoplasmic tail for the tail from a co-stimulatory molecule, such as CD28 (Prosser et al., 2012), may allow T cells to proliferate, survive or exert effector functions despite the presence of abundant inhibitory ligands within the TME. These engineering approaches are also applicable to cytokine receptors. T cells engineered to express a dominant negative TGFβ receptor (Foster et al., 2008) or a chimeric cytokine receptor such as a one with GM-CSF or IL-4 receptor ectodomains and IL-2R or IL-7R endodomains (Cheng and Greenberg, 2002; Leen et al., 2014; Mohammed et al., 2017; Wilkie et al., 2010) could allow T cells to co-opt suppressive cues within the tumor milieu to enhance function. Combining many of these approaches, such as cell engineering with reagents that improve T cell infiltration, modify the immunosuppressive TME, and/or enhance the endogenous immune response may yield synergistic effects on tumor control and overall survival. Studies examining combinatorial therapeutic strategies in preclinical models that recapitulate the most relevant features of the human disease have the potential to elucidate treatment regimens that should have the most potential for success in patients.

One remaining substantive obstacle is that T cells, after entering solid tumors, must overcome not only the immunosuppressive pathways that interfere with functional antitumor immune responses but also the dysfunction that derives from chronic TCR signaling. Blockade of inhibitory pathways that negatively regulate TCR signaling may prolong T cell function within the TME, but this may also sustain TCR signaling in the tumor-reactive T cells, possibly leading to more profound T cell exhaustion and/or dysfunction, and indeed it appears that such blockade may only transiently restore function (Pauken et al., 2016). However, T cell engineering should allow testing strategies that interrupt chronic TCR signaling within tumors, such as with regulated TCR expression under the control of conditional and tunable promoters (Benabdellah et al., 2016; Hoseini et al., 2015; Roybal et al., 2016), and may make it possible to prevent acquisition of irreversible T cell dysfunction. Given the heterogeneity and TME complexity across the landscape of solid tumors, much remains to be discovered about the relationship between cancer immunity and distinct TMEs. Advances in T cell engineering, mouse modeling and single cell analysis should reveal additional critical insights about this dynamic interplay, as well as how to further manipulate it for therapeutic advantage.

Acknowledgments

Due to the broad scope of this perspective, we apologize for the omission of many primary references.

Funding

This work was supported by the Chromosome Metabolism and Cancer Training Grant Program (T32 2T32CA009657-26A1 to K.G.A), a Solid Tumor Translational Research Award (to K.G.A. and P.D.G.), an Irvington Institute Fellowship Program of the Cancer Research Institute (to I.M.S), the Jack and Sylvia Paul Estate Fund to Support Collaborative Immunotherapy Research (to I.M.S.), the NIH National Cancer Institute (CA018029 and CA033084 to P.D.G), the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (16-65-GREE to P.D.G.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baitsch L, Baumgaertner P, Devevre E, Raghav SK, Legat A, Barba L, Wieckowski S, Bouzourene H, Deplancke B, Romero P, et al. Exhaustion of tumor-specific CD8(+) T cells in metastases from melanoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2350–2360. doi: 10.1172/JCI46102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayne LJ, Beatty GL, Jhala N, Clark CE, Rhim AD, Stanger BZ, Vonderheide RH. Tumor-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid inflammation and T cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:822–835. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty GL, Haas AR, Maus MV, Torigian DA, Soulen MC, Plesa G, Chew A, Zhao Y, Levine BL, Albelda SM, et al. Mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor mRNA-engineered T cells induce anti-tumor activity in solid malignancies. Cancer immunology research. 2014;2:112–120. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JC, Andersen MH, Schrama D, Thor Straten P. Immune-suppressive properties of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:1137–1148. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1434-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benabdellah K, Munoz P, Cobo M, Gutierrez-Guerrero A, Sanchez-Hernandez S, Garcia-Perez A, Anderson P, Carrillo-Galvez AB, Toscano MG, Martin F. Lent-On-Plus Lentiviral vectors for conditional expression in human stem cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37289. doi: 10.1038/srep37289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengsch B, Johnson AL, Kurachi M, Odorizzi PM, Pauken KE, Attanasio J, Stelekati E, McLane LM, Paley MA, Delgoffe GM, Wherry EJ. Bioenergetic Insufficiencies Due to Metabolic Alterations Regulated by the Inhibitory Receptor PD-1 Are an Early Driver of CD8(+) T Cell Exhaustion. Immunity. 2016;45:358–373. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstorff WV, Glickman JN, Odze RD, Farraye FA, Joo HG, Goedegebuure PS, Eberlein TJ. Fas (CD95/APO-1) and Fas ligand expression in normal pancreas and pancreatic tumors. Implications for immune privilege and immune escape. Cancer. 2002;94:2552–2560. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beura LK, Hamilton SE, Bi K, Schenkel JM, Odumade OA, Casey KA, Thompson EA, Fraser KA, Rosato PC, Filali-Mouhim A, et al. Normalizing the environment recapitulates adult human immune traits in laboratory mice. Nature. 2016;532:512–516. doi: 10.1038/nature17655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Y, Yu Y, Wang S, Li L. Up-regulation of fatty acid synthase induced by EGFR/ERK activation promotes tumor growth in pancreatic cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463:612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn SD, Shin H, Haining WN, Zou T, Workman CJ, Polley A, Betts MR, Freeman GJ, Vignali DA, Wherry EJ. Coregulation of CD8+ T cell exhaustion by multiple inhibitory receptors during chronic viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:29–37. doi: 10.1038/ni.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar L, Stanczak A, Cierniak S, Smoter M, Cichowicz M, Kozlowski W, Szczylik C, Wieczorek M, Lamparska-Przybysz M. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway as a potential prognostic and predictive marker in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2014;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boj SF, Hwang CI, Baker LA, Chio II, Engle DD, Corbo V, Jager M, Ponz-Sarvise M, Tiriac H, Spector MS, et al. Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2015;160:324–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A, Singer K, Koehl GE, Kolitzus M, Schoenhammer G, Thiel A, Matos C, Bruss C, Klobuch S, Peter K, et al. LDHA-Associated Lactic Acid Production Blunts Tumor Immunosurveillance by T and NK Cells. Cell Metab. 2016;24:657–671. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody JR, Costantino CL, Berger AC, Sato T, Lisanti MP, Yeo CJ, Emmons RV, Witkiewicz AK. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in metastatic malignant melanoma recruits regulatory T cells to avoid immune detection and affects survival. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1930–1934. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.12.8745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck MD, O’Sullivan D, Pearce EL. T cell metabolism drives immunity. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1345–1360. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckanovich RJ, Facciabene A, Kim S, Benencia F, Sasaroli D, Balint K, Katsaros D, O’Brien-Jenkins A, Gimotty PA, Coukos G. Endothelin B receptor mediates the endothelial barrier to T cell homing to tumors and disables immune therapy. Nat Med. 2008;14:28–36. doi: 10.1038/nm1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr EL, Kelman A, Wu GS, Gopaul R, Senkevitch E, Aghvanyan A, Turay AM, Frauwirth KA. Glutamine uptake and metabolism are coordinately regulated by ERK/MAPK during T lymphocyte activation. J Immunol. 2010;185:1037–1044. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho KC, Cunha IW, Rocha RM, Ayala FR, Cajaiba MM, Begnami MD, Vilela RS, Paiva GR, Andrade RG, Soares FA. GLUT1 expression in malignant tumors and its use as an immunodiagnostic marker. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:965–972. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000600008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cham CM, Driessens G, O’Keefe JP, Gajewski TF. Glucose deprivation inhibits multiple key gene expression events and effector functions in CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2438–2450. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Pearce EL. Emerging concepts of T cell metabolism as a target of immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:364–368. doi: 10.1038/ni.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Qiu J, O’Sullivan D, Buck MD, Noguchi T, Curtis JD, Chen Q, Gindin M, Gubin MM, van der Windt GJ, et al. Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell. 2015;162:1229–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman NM, Connolly SF, Reinl EL, Houtman JC. Focal adhesion kinase negatively regulates Lck function downstream of the T cell antigen receptor. J Immunol. 2013;191:6208–6221. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapuis AG, Ragnarsson GB, Nguyen HN, Chaney CN, Pufnock JS, Schmitt TM, Duerkopp N, Roberts IM, Pogosov GL, Ho WY, et al. Transferred WT1-Reactive CD8+ T Cells Can Mediate Antileukemic Activity and Persist in Post-Transplant Patients. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:174ra127. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng LE, Greenberg PD. Selective delivery of augmented IL-2 receptor signals to responding CD8+ T cells increases the size of the acute antiviral response and of the resulting memory T cell pool. J Immunol. 2002;169:4990–4997. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Lee YS, Kim J, Chung JY, Kim JH. Overexpression of glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) predicts poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Invest. 2013;31:607–615. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2013.849722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CK, Schietinger A, Liggitt HD, Tan X, Funk S, Freeman GJ, Ratliff TL, Greenberg NM, Greenberg PD. Cell-intrinsic abrogation of TGF-beta signaling delays but does not prevent dysfunction of self/tumor-specific CD8 T cells in a murine model of autochthonous prostate cancer. J Immunol. 2012;189:3936–3946. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R, Neuzillet C, Tijeras-Raballand A, Faivre S, de Gramont A, Raymond E. Targeting cancer cell metabolism in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:16832–16847. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colegio OR, Chu NQ, Szabo AL, Chu T, Rhebergen AM, Jairam V, Cyrus N, Brokowski CE, Eisenbarth SC, Phillips GM, et al. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature. 2014;513:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature13490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MA, Bednar F, Zhang Y, Brisset JC, Galban S, Galban CJ, Rakshit S, Flannagan KS, Adsay NV, Pasca di Magliano M. Oncogenic Kras is required for both the initiation and maintenance of pancreatic cancer in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:639–653. doi: 10.1172/JCI59227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrales L, Matson V, Flood B, Spranger S, Gajewski TF. Innate immune signaling and regulation in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2017;27:96–108. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, Evdemon-Hogan M, Conejo-Garcia JR, Zhang L, Burow M, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley D, Zambirinis CP, Seifert L, Akkad N, Mohan N, Werba G, Barilla R, Torres-Hernandez A, Hundeyin M, Mani VR, et al. gammadelta T Cells Support Pancreatic Oncogenesis by Restraining alphabeta T Cell Activation. Cell. 2016;166:1485–1499 e1415. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Yadley AH, Abbott AM, Pimiento JM, Chen DT, Malafa MP. Increased Expression of the Glucose Transporter Type 1 Gene Is Associated With Worse Overall Survival in Resected Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2016;45:974–979. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Chandel NS. Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci Adv. 2016;2:e1600200. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eil R, Vodnala SK, Clever D, Klebanoff CA, Sukumar M, Pan JH, Palmer DC, Gros A, Yamamoto TN, Patel SJ, et al. Ionic immune suppression within the tumour microenvironment limits T cell effector function. Nature. 2016;537:539–543. doi: 10.1038/nature19364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston R, Inman GJ. Crosstalk between p53 and TGF-beta Signalling. J Signal Transduct. 2012;2012:294097. doi: 10.1155/2012/294097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmrich J, Weber I, Nausch M, Sparmann G, Koch K, Seyfarth M, Lohr M, Liebe S. Immunohistochemical characterization of the pancreatic cellular infiltrate in normal pancreas, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Digestion. 1998;59:192–198. doi: 10.1159/000007488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ene-Obong A, Clear AJ, Watt J, Wang J, Fatah R, Riches JC, Marshall JF, Chin-Aleong J, Chelala C, Gribben JG, et al. Activated pancreatic stellate cells sequester CD8+ T cells to reduce their infiltration of the juxtatumoral compartment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1121–1132. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JI, Carmichael M, Partin AW. OA-519 (fatty acid synthase) as an independent predictor of pathologic state in adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Urology. 1995;45:81–86. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(95)96904-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Kamphorst JJ, Mathew R, Chung MK, White E, Shlomi T, Rabinowitz JD. Glutamine-driven oxidative phosphorylation is a major ATP source in transformed mammalian cells in both normoxia and hypoxia. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:712. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig C, Jones JO, Kraman M, Wells RJ, Deonarine A, Chan DS, Connell CM, Roberts EW, Zhao Q, Caballero OL, et al. Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20212–20217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320318110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng K, Guo Y, Dai H, Wang Y, Li X, Jia H, Han W. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for the immunotherapy of patients with EGFR-expressing advanced relapsed/refractory non-small cell lung cancer. Sci China Life Sci. 2016;59:468–479. doi: 10.1007/s11427-016-5023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipp FV, Ratnikov B, De Ingeniis J, Smith JW, Osterman AL, Scott DA. Glutamine-fueled mitochondrial metabolism is decoupled from glycolysis in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25:732–739. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K, Hoffmann P, Voelkl S, Meidenbauer N, Ammer J, Edinger M, Gottfried E, Schwarz S, Rothe G, Hoves S, et al. Inhibitory effect of tumor cell-derived lactic acid on human T cells. Blood. 2007;109:3812–3819. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes SA, Bindal N, Bamford S, Cole C, Kok CY, Beare D, Jia M, Shepherd R, Leung K, Menzies A, et al. COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D945–950. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster AE, Dotti G, Lu A, Khalil M, Brenner MK, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Bollard CM. Antitumor activity of EBV-specific T lymphocytes transduced with a dominant negative TGF-beta receptor. J Immunother. 2008;31:500–505. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318177092b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame MC, Patel H, Serrels B, Lietha D, Eck MJ. The FERM domain: organizing the structure and function of FAK. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2010;11:802–814. doi: 10.1038/nrm2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon J, Angell HK, Bedognetti D, Marincola FM. The continuum of cancer immunosurveillance: prognostic, predictive, and mechanistic signatures. Immunity. 2013;39:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gansler TS, Hardman W, 3rd, Hunt DA, Schaffel S, Hennigar RA. Increased expression of fatty acid synthase (OA-519) in ovarian neoplasms predicts shorter survival. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:686–692. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(97)90177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger R, Rieckmann JC, Wolf T, Basso C, Feng Y, Fuhrer T, Kogadeeva M, Picotti P, Meissner F, Mann M, et al. L-Arginine Modulates T Cell Metabolism and Enhances Survival and Anti-tumor Activity. Cell. 2016;167:829–842 e813. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano M, Henin C, Maurizio J, Imbratta C, Bourdely P, Buferne M, Baitsch L, Vanhille L, Sieweke MH, Speiser DE, et al. Molecular profiling of CD8 T cells in autochthonous melanoma identifies Maf as driver of exhaustion. Embo J. 2015;34:2042–2058. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann U, Fallarino F, Puccetti P. Tolerance, DCs and tryptophan: much ado about IDO. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:242–248. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaumond F, Leca J, Olivares O, Lavaut MN, Vidal N, Berthezene P, Dusetti NJ, Loncle C, Calvo E, Turrini O, et al. Strengthened glycolysis under hypoxia supports tumor symbiosis and hexosamine biosynthesis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3919–3924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219555110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirnalda P, Wood L, Goenka R, Crespo J, Paterson Y. Interferon gamma-induced intratumoral expression of CXCL9 alters the local distribution of T cells following immunotherapy with Listeria monocytogenes. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e25752. doi: 10.4161/onci.25752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson AJ, Kaneda MM, Tsujikawa T, Nguyen AV, Affara NI, Ruffell B, Gorjestani S, Liudahl SM, Truitt M, Olson P, et al. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK)-dependent immune cell crosstalk drives pancreas cancer. Cancer discovery. 2015 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad R, Saldanha-Araujo F. Mechanisms of T-cell immunosuppression by mesenchymal stromal cells: what do we know so far? Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:216806. doi: 10.1155/2014/216806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R, Wolchok JD, Hersey P, Joseph RW, Weber JS, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Coussens LM. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlin H, Meng Y, Peterson AC, Zha Y, Tretiakova M, Slingluff C, McKee M, Gajewski TF. Chemokine expression in melanoma metastases associated with CD8+ T-cell recruitment. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3077–3085. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Duan X, Guo N, Chan C, Poon C, Weichselbaum RR, Lin W. Core-shell nanoscale coordination polymers combine chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy to potentiate checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12499. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley CT, Wasti AT, DeBerardinis RJ. Glutamine and cancer: cell biology, physiology, and clinical opportunities. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3678–3684. doi: 10.1172/JCI69600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho PC, Bihuniak JD, Macintyre AN, Staron M, Liu X, Amezquita R, Tsui YC, Cui G, Micevic G, Perales JC, et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate Is a Metabolic Checkpoint of Anti-tumor T Cell Responses. Cell. 2015;162:1217–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodis E, Watson IR, Kryukov GV, Arold ST, Imielinski M, Theurillat JP, Nickerson E, Auclair D, Li L, Place C, et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell. 2012;150:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgaard RB, Zamarin D, Li Y, Gasmi B, Munn DH, Allison JP, Merghoub T, Wolchok JD. Tumor-Expressed IDO Recruits and Activates MDSCs in a Treg-Dependent Manner. Cell Rep. 2015;13:412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoseini SS, Hapke M, Herbst J, Wedekind D, Baumann R, Heinz N, Schiedlmeier B, Vignali DA, van den Brink MR, Schambach A, et al. Inducible T-cell receptor expression in precursor T cells for leukemia control. Leukemia. 2015;29:1530–1542. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo W, Zaretsky JM, Sun L, Song C, Moreno BH, Hu-Lieskovan S, Berent-Maoz B, Pang J, Chmielowski B, Cherry G, et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Features of Response to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma. Cell. 2016;165:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain Z, Huang Y, Seth P, Sukhatme VP. Tumor-derived lactate modifies antitumor immune response: effect on myeloid-derived suppressor cells and NK cells. J Immunol. 2013;191:1486–1495. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba T, Ino K, Kajiyama H, Yamamoto E, Shibata K, Nawa A, Nagasaka T, Akimoto H, Takikawa O, Kikkawa F. Role of the immunosuppressive enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in the progression of ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenzi D, Alo PL, Balzani A, Sebastiani V, Silipo V, La Torre G, Ricciardi G, Bosman C, Calvieri S. Fatty acid synthase expression in melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:23–28. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.300104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs SR, Herman CE, Maciver NJ, Wofford JA, Wieman HL, Hammen JJ, Rathmell JC. Glucose uptake is limiting in T cell activation and requires CD28-mediated Akt-dependent and independent pathways. J Immunol. 2008;180:4476–4486. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Hegde S, Knolhoff BL, Zhu Y, Herndon JM, Meyer MA, Nywening TM, Hawkins WG, Shapiro IM, Weaver DT, et al. Targeting focal adhesion kinase renders pancreatic cancers responsive to checkpoint immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nm.4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaech SM, Cui W. Transcriptional control of effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:749–761. doi: 10.1038/nri3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaira K, Nakamura K, Hirakawa T, Imai H, Tominaga H, Oriuchi N, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, Tsukamoto N, Oyama T, et al. Prognostic significance of L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) expression in patients with ovarian tumors. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7:1161–1171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]