Abstract

Objective Uterine tamponade by fluid-filled balloons is now an accepted method of controlling postpartum hemorrhage. Available tamponade balloons vary in design and material, which affects the filling attributes and volume at which they rupture. We aimed to characterize the filling capacity and pressure-volume relationship of various tamponade balloons.

Study Design Balloons were filled with water ex vivo. Intraluminal pressure was measured incrementally (every 10 mL for the Foley balloons and every 50 mL for all other balloons). Balloons were filled until they ruptured or until 5,000 mL was reached.

Results The Foley balloons had higher intraluminal pressures than the larger-volume balloons. The intraluminal pressure of the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube (gastric balloon) was initially high, but it decreased until shortly before rupture occurred. The Bakri intraluminal pressure steadily increased until rupture occurred at 2,850 mL. The condom catheter, BT-Cath, and ebb all had low intraluminal pressures. Both the BT-Cath and the ebb remained unruptured at 5,000 mL.

Conclusion In the setting of acute hemorrhage, expeditious management is critical. Balloons that have a low intraluminal pressure-volume ratio may fill more rapidly, more easily, and to greater volumes. We found that the BT-Cath, the ebb, and the condom catheter all had low intraluminal pressures throughout filling.

Keywords: postpartum hemorrhage, uterine balloon, uterine tamponade, uterine tamponade balloon, uterine balloon tamponade, Bakri balloon, ebb balloon, BT-Cath, intraluminal pressure

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) affects 2.9 to 4.3% of deliveries in North America with 0.3% characterized as severe,1 2 3 and it consistently ranks among the leading causes of pregnancy-related deaths in both developed and low-resource countries.4 5 The initial approach to management is the stepwise exclusion of the most common causes, namely retained products of conception, genital tract trauma, and uterine atony, with atony being the most common etiology of PPH. It follows that uterotonic agents are frequently the first-line treatment given their availability, low cost, and ease of administration; however, when they fail or when uterotonics are contraindicated for medical reasons, mechanical methods such as uterine tamponade have been shown to be effective in decreasing hemorrhage due to uterine atony.6

Uterine tamponade is not new,7 8 but uterine balloon tamponade is a relatively recent addition to our armamentarium for the management of PPH. The first description of uterine balloon tamponade was published in 19519; the first balloon specifically designed for this indication was described in 199910 11 and approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2006. Uterine tamponade balloons are thought to work by reducing uterine artery perfusion pressure, either by direct compression of the artery in the lower segment or by wall conformational changes.12 Multiple balloons are currently available; however, they are variable in their ease of use. Challenges during balloon filling include the requirement to apply high amounts of physical force to, and repeatedly fill and empty, the syringe used to deliver the fluid to expand the balloon, which can cause delay in achieving adequate tamponade. Balloons that are not designed for PPH management are often simple to use but frequently have a low-volume capacity, which necessitates the placement of multiple balloons. Balloons that were designed for PPH management allow infusion of an adequate volume of fluid to tamponade the postpartum uterus and have a wide-caliber catheter to allow easy drainage of blood from above the balloon when it is inflated inside the uterus. However, both PPH-specific and simpler balloons can be difficult to fill due to high intraluminal pressures in the system.

The purpose of this study was to (1) measure the intraluminal pressure of each balloon during filling and (2) assess the maximum filling volume (defined as either the volume at which balloon rupture occurred, or at 5,000 mL if no rupture occurred).

Methods

This study was performed at Ben Taub Hospital in the Harris Health System in 2013. This study was exempt by the institutional review board at Baylor College of Medicine as it did not involve human subjects.

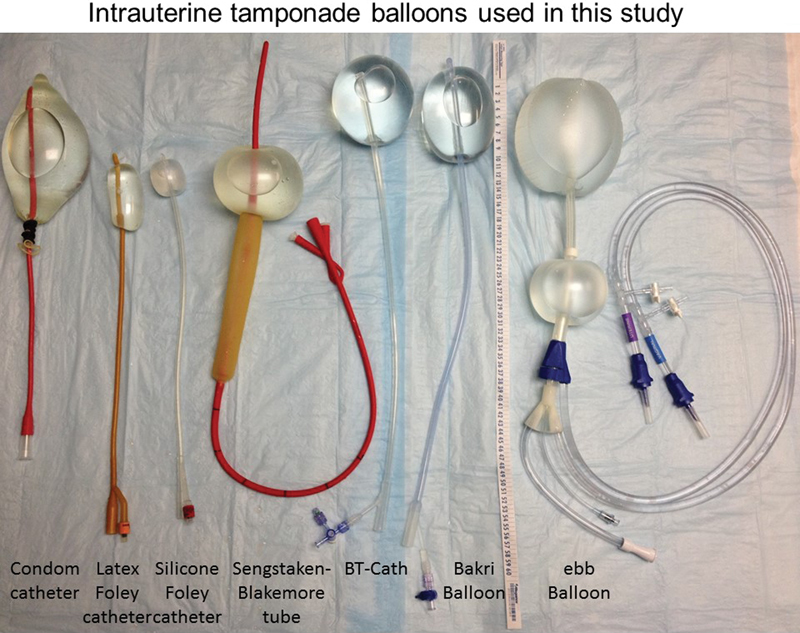

Eligible balloons were selected based on reports from the literature13 14 and from a search for new FDA-approved PPH uterine tamponade balloons. The condom catheter, also reported in the literature, was also tested.15 Included balloons are shown in Fig. 1 and include the condom catheter, latex Foley catheter, silicone Foley catheter, the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube (Bard, Covington, GA), the BT-Cath (Utah Medical Products, Midvale, UT), the Bakri balloon (Cook, Spencer, IN), and the ebb balloon (Glenveigh, Chattanooga, TN). The Rusch urologic catheter (without a drainage tip), which has also been reported in the literature, was not available in the United States; thus, it was not included. Available catheters were purchased or obtained from the manufacturers or from the hospital labor and delivery unit.

Fig. 1.

Intrauterine tamponade balloons used in this study. The condom catheter is shown filled to 500 mL of fluid (with a urologic syringe cover blocking extrusion of fluid). Unlike the other balloons in this study, the condom catheter has no drainage tip. The latex and silicone Foley pictured here each contains 30 mL of fluid. The Sengstaken is shown with only the gastric balloon filled to 300 mL. The BT-Cath's drainage tip is flush with the end of the balloon; here it is filled to 500 mL of fluid. The Bakri balloon is also filled to 500 mL. The ebb is filled to 750 mL in the uterine balloon and 300 mL in the vaginal balloon. The ebb's drainage tip protrudes from the end of the balloon initially, but as the balloon fills, it no longer protrudes. The vaginal balloon can also slide superiorly toward the uterine balloon (not shown).

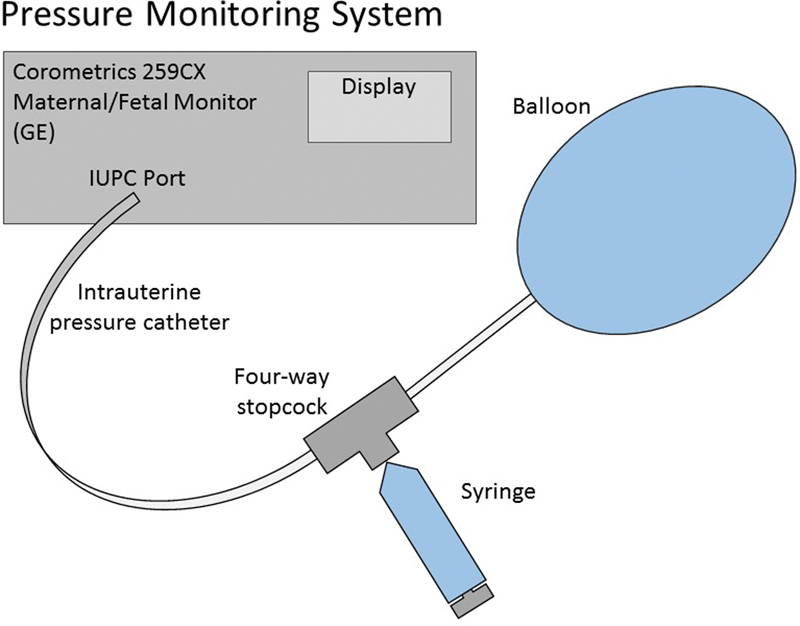

Pressure Monitoring System

The pressure sensor of a Corometrics 259CX Series Maternal/Fetal Monitor (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) was connected to a Koala IPC 5000 Intrauterine Pressure System (Clinical Innovations, Inc., Murray, UT) to document intraluminal pressure. The Koala catheter has a multifenestrated tip intended for the measurement of intrauterine pressure. Given that it was used in this instance to obtain intraluminal pressure, it was cut at 7 cm of length to remove the fenestrated tip, allowing placement into a linear pressure system. The cut tip was inserted into one port of a four-way stopcock (CareFusion, Switzerland) (Fig. 2). The second port of the stopcock was attached via a Luer lock to the syringes which were used to infuse room temperature water into the balloons. The third Luer lock of the stopcock was attached to the infusion port of the balloons. Using this system, the “closed” port could be rotated to the intrauterine pressure catheter system (the first port) to allow infusion of the balloon. The “closed” port was then rotated to the syringe port (the second port) to allow measurement of intraluminal pressure and also allowed the syringe to be refilled.

Fig. 2.

The pressure sensor of a Corometrics 259CX Series Maternal/Fetal Monitor was connected to a Koala IPC 5000 Intrauterine Pressure System to document intraluminal pressure. The cut tip of the catheter was inserted into the first port of a four-way stopcock. The second port of the stopcock was attached via a Luer lock to the syringes that were used to infuse water into the balloons. The third Luer lock of the stopcock was attached to the infusion port of the balloons.

The small balloons (the silicone and latex Foley catheter balloons) were inflated with 10-mL boluses of room temperature water prior to each measurement, whereas the larger balloons (Bakri, ebb, BT-Cath, condom catheter, and Sengstaken) were inflated with 50 mL prior to each measurement. Following the fluid infusion, the intraluminal pressure of the balloons was measured via the intrauterine pressure system by rotating the “closed” port of the four-way stopcock to the side of the infusion syringe.

Each balloon was filled at the predetermined volume until either rupture occurred or until 5,000 mL was reached if rupture did not occur prior to achieving this volume. A maximum of 5,000 mL was determined to be the maximum clinically usable volume and was thus the predetermined stopping point.

Uterine Tamponade Balloons

Though there are multiple types of Foley catheters commercially available, the two tested in this study were those available at our institution. The Bard Foley catheter (Bard, Covington, GA) is a silicone-coated latex catheter. The manufacturer's recommended inflation capacity is 35 mL.16 As it contains natural rubber latex, it may cause allergic reactions. Thus, an all-silicone alternative is frequently available. The Bardex all-silicone Foley catheter (Bard, Covington, GA) is a non-latex Foley catheter. The manufacturer's recommended inflation capacity is 10 mL.16 Given the low volumes of these balloons, typically multiple (5–10) are placed for the management of PPH. In this study, the intraluminal pressure within each Foley catheter was measured following each 10 mL infusion until rupture occurred. Because rupture occurred during inflation, the exact rupture pressure could not be measured as the pressure port was closed during inflation. The volume and pressure of rupture were thus recorded as the volume and pressure recorded immediately prior to the inflation volume at which rupture occurred.

The use of the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube in uterine tamponade has been variably reported by different authors.14 17 18 19 The long drainage catheter tip (which is designed to sit in the stomach) is frequently (but not always) cut close to the gastric balloon. Both balloons are placed into the uterine cavity. The gastric balloon is usually filled with up to 300 mL of fluid (recommended filling capacity is 300–400 mL), and in a few cases, the esophageal balloon is also filled (recommended filling capacity is 150 m). Given the inconsistent use of the esophageal balloon in clinical practice, we only measured the intraluminal pressure in the gastric balloon, and this was done after each 50 mL aliquot until rupture occurred.

A condom catheter was created using a Durex condom (Durex, Parsippany, NJ) with a Bard all-purpose urethral catheter (Bard, Covington, GA) as described by Rathore et al.20 21 Rathore et al20 21 tied a condom to the tip of a Foley catheter with suturing silk and inflated it with between 200 and 400 mL of fluid via the Foley catheter. The volume they used was determined by the clinical effect, and once bleeding was reduced, they clamped the Foley catheter and packed the vagina with gauze to keep the condom catheter in position.20 21 In our study, intraluminal pressure was measured after every 50 mL of volume infused until rupture occurred.

The Bakri balloon is a 24F, 54-cm-long silicone catheter with a balloon that has a stated capacity of 500 mL of fluid. The FDA approved this balloon for the management of PPH in 2006, and it was the first uterine tamponade balloon approved for this indication. It is designed to be placed in the uterine fundus either vaginally or through a hysterotomy (at time of cesarean section).11 The balloon is filled with sterile liquid using the provided infusion port and syringe.22 In this study, intraluminal pressure was measured every 50 mL until rupture occurred.

The BT-Cath is a 24F, 152.4-cm long-silicone catheter with a balloon that has a stated capacity of 500 mL of fluid. It received FDA approval in 2011. The BT-Cath with the EasyFill inflation system23 was used in this study, and although the system allows 500 mL of fluid to be infused at once without the need for multiple syringe refills and pushes, to obtain an accurate pressure measurement after every 50 mL aliquot, here the balloon was filled using a syringe.

The ebb is a 15-French (distal tip), 30F (catheter), 84-cm-long polyurethane catheter with a balloon that has a stated capacity of 750 mL of fluid. It received FDA approval in 2010. Though it has dual balloons to control both vaginal and uterine bleeding, in this study we only measured the pressure-volume relationship in the uterine balloon.24 The ebb has filling system that allows continuous filling to the maximum capacity, but for the purposes of this study, it was filled using the same system as was used to inflate the BT-Cath (syringe to allow intraluminal pressure measurements every 50 mL).

Results

The manufacturer's recommended maximum filling capacity and the volume and intraluminal pressure just before the inflation period that resulted in rupture are shown in Table 1. The pressure-volume filling curves of the Foley catheter balloons are shown in Fig. 3. The silicone Foley catheter balloons ruptured just beyond a volume of 50 mL, whereas the latex Foley catheters ruptured at just beyond a volume of 120 mL. Both types of Foley catheter ruptured at pressures that exceeded 375 mm Hg. Both types of Foley catheter also had high filling pressures starting at 10 mL. The intraluminal pressure of the silicone Foley catheters continued to rise until rupture, whereas the latex Foley catheters showed a decrease in intraluminal pressure from 10 to 50 mL followed by a steady increase. Both latex Foley catheters ruptured at 120 mL.

Table 1. Manufacturers' recommended filling capacity and the volume and pressure at rupture.

| Balloon description | Manufacturer city/state | Item number ordering Information | Recommended maximum filling volume per instructions for use | Rupture volume | Rupture pressure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bardex all-silicone Foley catheter 1 | Bard Covington, GA |

165816 16 Ch/F (5.3 mm) 5 mL ribbed balloon |

10 mL | 50 mL | 486 mm Hg |

| Bardex all-silicone Foley catheter 2 | Bard Covington, GA |

165816 16 Ch/F (5.3 mm) 5 mL ribbed balloon |

10 mL | 50 mL | 378 mm Hg |

| Bard Foley Catheter (latex with silicone coating) 1 | Bard Covington, GA |

266716 16F. Silicone Coated |

35 mL | 120 mL | 377 mm Hg |

| Bard Foley catheter (latex with silicone coating) 2 | Bard Covington, GA |

266716 16F. silicone coated |

35 mL | 120 mL | 378 mm Hg |

| Sengstaken esophageal-nasogastric tube *Gastric balloon only |

Bard Covington, GA |

0092030 20F. Adult X-ray opaque rubber |

250 mL | 3,350 | 61 |

| Durex condom Enhanced pleasure 1 latex condom With Bard all-purpose urethral catheter with funnel end 16' length, two eyes |

Durex Parsippany, NJ Bard Covington, GA |

TN/DRUGS/6/64 0094160 16F X-ray opaque rubber |

– | 4,750 | −3 |

| Bakri postpartum balloona | Cook OB/GYN Spencer, IN |

J-SOS-100500 GPN REF G306673 |

500 mL | 2,850 mL | 64 mm Hg |

| BT-Cath Balloon tamponade catheter for postpartum uterine hemorrhage with EasyFill inflation systema |

Utah Medical Products, Inc. Midvale, UT |

BTC-ESY | 500 | > 5,000 | 17 |

| ebb Complete tamponade system BD-OTS obstetric cathetera *Uterine balloon only |

Glenveigh Medical Chattanooga, TN |

CTS-1000 | 750 mL | > 5,000 mL | 9 mm Hg |

FDA approved for management of postpartum hemorrhage.

Fig. 3.

Pressure-volume curves of the Foley catheters. Both Foleys had high filling pressures starting at 10 mL, but the silicone Foley continued to rise and ruptured after 50 mL. The latex Foley had a decrease in pressure from 10 to 50 mL followed by a steady increase. Both latex Foley catheters ruptured at 120 mL. X indicates the recommended filling volume.

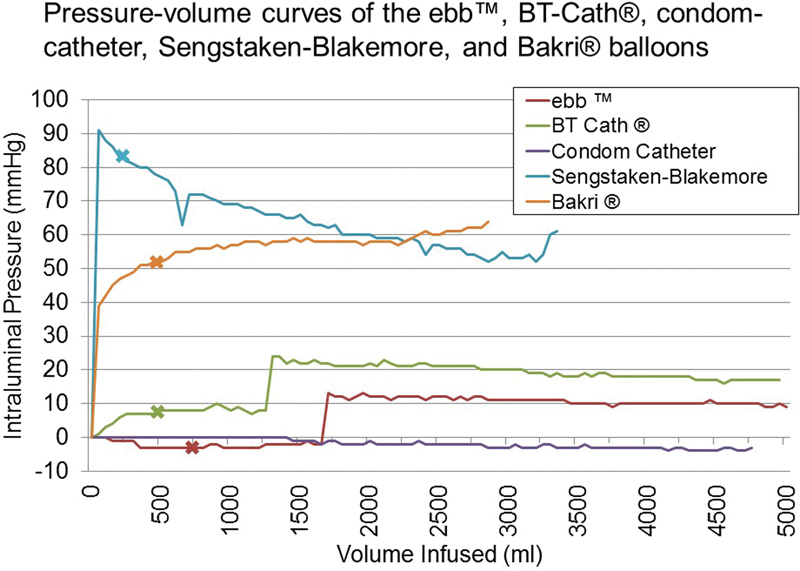

Fig. 4 shows the pressure-volume curves of the balloons in the Sengstaken, condom catheter, Bakri, BT-Cath, and ebb. The intraluminal pressure in the Sengstaken balloon was initially high, but it decreased until shortly before rupture occurred at 3,350 mL. The condom catheter had low intraluminal pressures until rupture occurred at 4,750 mL. The intraluminal pressure in the Bakri balloon steadily increased until rupture occurred at 2,850 mL. The BT-Cath had initially low intraluminal pressure until a slight but sudden increase occurred between 1,250 and 1,300 mL. The ebb had a similar slight but sudden increase in intraluminal pressure that occurred between 1,650 and 1,700 mL and plateaued around 10 mm Hg. Neither the BT-Cath nor the ebb ruptured; thus, the pressures were recorded at 5,000 mL.

Fig. 4.

Pressure-volume curves of the Sengstaken, condom catheter, Bakri, BT-Cath, and ebb balloons. The Sengstaken's intraluminal pressure was initially high but decreased until shortly before rupture occurred at 3,350 mL. The condom catheter had negligible intraluminal pressures until rupture occurred at 4,750 mL. The Bakri's intraluminal pressure steadily increased until rupture occurred at 2,850 mL. The BT-Cath had initially low intraluminal pressures until a slight but sudden increase between 1,250 and 1,300 mL and did not rupture at 5,000 mL. The ebb had a similar slight but sudden increase in intraluminal pressure that occurred between 1,650 and 1,700 mL, and did not rupture at 5,000 mL. X indicates the recommended filling volume; the condom catheter does not have a recommended filling volume as it is not FDA-approved.

Discussion

Uterine tamponade balloons are emerging as a fertility-sparing and lifesaving option in the management of PPH. Recent literature has shown an overall success rate of 75 to 94% at avoiding embolization or hysterectomy.25 26 27 28 29 30 Even if tamponade fails to completely stop hemorrhage, it may reduce bleeding and provide temporary respite, such that resuscitative efforts can be effective while arranging more definitive management. This study sought to assess the intraluminal pressure necessary to expand a selection of the currently available balloons ex vivo and to measure the maximum filling volume of these balloons at approximately the time of rupture or the attainment of a volume of 5,000 mL. We found that balloon rupture occurred at much higher filling volumes than those recommended by the manufacturers.

Our findings are similar to those of other investigators. In 2010, Georgiou published a series of intraluminal pressure readings during the establishment of uterine tamponade using the Bakri balloon.31 He found a curvilinear relationship between the intraluminal pressure and the balloon volume in vitro, with similar findings in vivo in one of his two cases, and higher pressures in vivo in his other case.31 Ex vivo, the initial filling pressure peaked at 60 to 80 mm Hg with subsequent pressures not varying > 10 to 20 mm Hg.31 This is similar to the pressures we observed and is likely attributed to the high level of resistance to inflation of silicone (the balloon material). Belfort and colleagues12 also published a series of pressure-volume curves, using the ebb balloon wherein they found low initial filling pressures (< 35 mm Hg) with an exponential rise in the intraluminal pressure at subsequent volumes that did not exceed 59 mm Hg. Though our study was limited to ex vivo use, these findings correlate with prior studies, with a general trend toward lower filling pressure for the ebb.12 31 As noted previously, the intraluminal pressure can be impacted by external forces, such as fundal contractility.12 31

Whether there are medical risks to increased intraluminal pressure is unclear. If rupture were to occur under conditions of high balloon intraluminal pressure, it could result in embolization of fluid, but if normal saline is used to insufflate the balloons, as is recommended, this is unlikely to cause electrolyte imbalance.22 24 32 More worrisome would be the potential retention of ruptured balloon components or embolization of residual air which commonly exists in these systems.

Neither a high intraluminal pressure nor excessive volume is required to achieve adequate tamponade. Studies on the efficacy of tamponade balloons demonstrate adequate hemostasis at a wide range of volumes, most of which are well below the recommended maximum filling volume.25 27 28 29 30 Both Georgiou31 and Belfort et al12 demonstrated in vivo that uterine tamponade occurred when the intraluminal pressure was lower than the systolic blood pressure; furthermore, Belfort et al12 demonstrated reversal of uterine artery diastolic flow at intraluminal pressures that ranged from 40 to 70 mm Hg.12 31 Of note, all cases of reversed uterine artery diastolic flow in his series occurred at volumes > 1,000 mL, which exceeds the recommended limit of 750 mL for the ebb balloon.12 Perhaps in the future, higher maximum recommended limits may be permitted.

An unexpected finding of the study was the persistent intact status of the BT-Cath and ebb balloon at 5,000 mL. Both also maintained relatively low intraluminal pressures at 17 and 9 mm Hg, respectively. This volume exceeds the recommended capacity by 10-fold for the BT-Cath and 6.7-fold for the ebb, respectively, and 500 mL and 750 mL are appropriate capacity limits when filling the uterus. The effects of overfilling and distending the atonic uterus in an attempt to stop hemorrhage are not known, and further research in this area is required.

In 1936 Logothetopulos33 described the placement of an umbrella or parachute pack to place pressure on bleeding pelvic vessels to control post-hysterectomy hemorrhage. This practice continues in modern obstetrics, and it has been shown to be successful at managing post-hysterectomy bleeding.34 35 The current technique for pelvic tamponade involves filling a sterile X-ray cassette bag with gauze rolls knotted together to maximize volume and provide tamponade contact with the pelvic wall. The pack is introduced transabdominally with the stalk exiting the vagina. Traction is applied using a 1-L bag of saline that hangs over the foot of the bed. A urinary catheter is always placed to measure urine output and broad-spectrum antibiotics are initiated. Both the Bakri and the ebb tamponade balloon systems have been used off-label for a similar purpose and have been reported in the literature.27 36

Among FDA-approved uterine tamponade balloons, the ebb exhibited the lowest intraluminal pressure during inflation, but the value of this finding requires further research in vivo to understand its significance. Clearly there are several factors that affect filling pressure such as the residual tension in the uterine wall musculature, the elasticity and contractility of the muscle, whether or not there is chorioamnionitis, and which segment of the uterus is atonic (upper, lower or both). It is also possible that lower resistance balloon may be safely filled to higher than the recommended volumes without rupturing. Higher than recommended filling volumes have been reported in the literature,12 27 28 29 30 36 37 38 and our data demonstrate that of the non-Foley balloons, rupture did not occur until at least 2,850 mL had been instilled.

Maternal death from PPH has been determined to be preventable in 73 to 93% of cases in the United States.5 39 Early diagnosis and a systematic approach to management are critical to reducing morbidity and mortality. As the leading cause of PPH is uterine atony, if medical management fails or is contraindicated, an accelerated decision to proceed with uterine tamponade is warranted. To our knowledge, there are no reports of adverse effects due to balloon rupture, and it is unknown whether balloon rupture under conditions of high pressure could pose increased risk of fluid or air embolization, or retained foreign object. We believe that the ideal uterine tamponade device should be easily and rapidly fillable, accommodate adequate fluid volume under low intraluminal pressure, and not be prone to failure (rupture) under usual clinical conditions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Ben Taub Hospital and the nurses at Ben Taub Hospital Labor and Delivery unit for the use of space and equipment. We would also like to thank Ms. Sophie Dildy for her assistance with this project.

Footnotes

Financial Support Baylor College of Medicine Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Fellowship Research Funds (DRA and KMA) for the BT-Cath and Blakemore Catheter. Glenveigh provided the ebb balloons. Harris Health System provided the Bard Foley catheters, Bakri balloons, and the Koala intrauterine pressure catheter system.

Appendix

Other product information:

aKoala IPC 5000 Intrauterine Pressure System Information: Reorder No. IPC-5000E, Lot No. 130164, Expiration 2015–02.

†CareFusion Max Guard extension set with four-way stopcock information: Reference No. M4058, Lot No. 13075849, Expiration 2018–07.

References

- 1.Calvert C, Thomas S L, Ronsmans C, Wagner K S, Adler A J, Filippi V. Identifying regional variation in the prevalence of postpartum haemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(07):e41114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callaghan W M, Kuklina E V, Berg C J. Trends in postpartum hemorrhage: United States, 1994–2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(04):3530–3.53E8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kramer M S, Berg C, Abenhaim H et al. Incidence, risk factors, and temporal trends in severe postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(05):4490–4.49E9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Division of Reproductive Health Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NC for CDP and HP. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System: Causes of Pregnancy-Related Death in the United States, 2006–2009 Pregnancy Mortal Surveill Syst 200958972–975. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark S L, Belfort M A, Dildy G A, Herbst M A, Meyers J A, Hankins G D.Maternal death in the 21st century: causes, prevention, and relationship to cesarean delivery Am J Obstet Gynecol 200819901360–3.6E6., discussion 91–92, e7–e11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin: Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician Gynecologists Number 76, October 2006: postpartum hemorrhage Obstet Gynecol 2006108041039–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith W C. Uterine tamponade with oxidized gauze in a case of total separation of the placenta with concealed hemorrhage. N Y State J Med. 1949;49(18):2187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams W. New York, NY: Appleton and Company; 1903. Obstetrics: A Text-Book for Students and Practitioners. Operative Procedures Which Do Not Aim at Delivery. 1st ed. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holtz R S. The control of postpartum hemorrhage by the intrauterine balloon. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1951;62(02):450–451. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(51)90546-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakri Y N. Balloon device for control of obstetrical bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;86:84. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakri Y N, Amri A, Abdul Jabbar F. Tamponade-balloon for obstetrical bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;74(02):139–142. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00395-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belfort M A, Dildy G A, Garrido J, White G L. Intraluminal pressure in a uterine tamponade balloon is curvilinearly related to the volume of fluid infused. Am J Perinatol. 2011;28(08):659–666. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1276741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johanson R, Kumar M, Obhrai M, Young P. Management of massive postpartum haemorrhage: use of a hydrostatic balloon catheter to avoid laparotomy. BJOG. 2001;108(04):420–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georgiou C. Balloon tamponade in the management of postpartum haemorrhage: a review. BJOG. 2009;116(06):748–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akhter S, Begum M R, Kabir J. Condom hydrostatic tamponade for massive postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;90(02):134–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.BARD_Medical. BARD Foley Catheter Inflation/Deflation Guidelines http://www.bardmedical.com/Resources/Products/Documents/Brochures/Urology/Bard%20Foley%20Catheter%20Inflation_Deflation%20Guidelines.pdf. Accessed

- 17.Chan C, Razvi K, Tham K F, Arulkumaran S. The use of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube to control post-partum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;58(02):251–252. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(97)00090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Condie R G, Buxton E J, Payne E S. Successful use of Sengstaken-Blakemore tube to control massive postpartum haemorrhage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101(11):1023–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1994.tb13058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katesmark M, Brown R, Raju K S. Successful use of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube to control massive postpartum haemorrhage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101(03):259–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1994.tb13124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rathore A M, Gupta S, Manaktala U, Gupta S, Dubey C, Khan M. Uterine tamponade using condom catheter balloon in the management of non-traumatic postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38(09):1162–1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsubara S. Available hemostatic measures for postpartum hemorrhage in rural settings. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:2248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.COOK_Medical. Bakri Postpartum Balloon Package Insert https://www.cookmedical.com/data/IFU_PDF/U_J-SOS_REV2PDF.2010. Accessed February 2, 2014

- 23.Utah_Medical. BT-Cath Balloon Tamponade Catheter for Postpartum Hemorrhage Brochure http://www.utahmed.com/pdf/58304.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2014

- 24.Glenveigh_Medical. ebb Complete Tamponade System by Belfort and Dildy. http://glenveigh.com/ebb-product-package-insert.pdf. 2011. Accessed February 2, 2014

- 25.Grönvall M, Tikkanen M, Tallberg E, Paavonen J, Stefanovic V. Use of Bakri balloon tamponade in the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: a series of 50 cases from a tertiary teaching hospital. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(04):433–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright C E, Chauhan S P, Abuhamad A Z. Bakri balloon in the management of postpartum hemorrhage: a review. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31(11):957–964. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dildy G A, Belfort M A, Adair C D et al. Initial experience with a dual-balloon catheter for the management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(02):1360–1.36E8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Revert M, Cottenet J, Raynal P, Cibot E, Quantin C, Rozenberg P.Intrauterine balloon tamponade for management of severe postpartum haemorrhage in a perinatal network: a prospective cohort study BJOG 2016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Cho H Y, Park Y W, Kim Y H, Jung I, Kwon J Y. Efficacy of intrauterine Bakri balloon tamponade in cesarean section for placenta previa patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(08):e0134282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alkış İ, Karaman E, Han A, Ark H C, Büyükkaya B. The fertility sparing management of postpartum hemorrhage: a series of 47 cases of Bakri balloon tamponade. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54(03):232–235. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Georgiou C. Intraluminal pressure readings during the establishment of a positive ‘tamponade test’ in the management of postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG. 2010;117(03):295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munro M G, Storz K, Abbott J A et al. AAGL Practice Report: Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hysteroscopic Distending Media: (Replaces Hysteroscopic Fluid Monitoring Guidelines. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2000;7:167–168) J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(02):137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Logothetopulos K. Eine absolut sichere Blutstillungsmethode bei vaginalen und abdominalen gynakologischen Operationen. Zentralbl Gynakol. 1926;50:3202. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howard R J, Straughn J M, Jr, Huh W K, Rouse D J.Pelvic umbrella pack for refractory obstetric hemorrhage secondary to posterior uterine rupture Obstet Gynecol 2002100(5 Pt 2):1061–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dildy G A, Scott J R, Saffer C S, Belfort M A. An effective pressure pack for severe pelvic hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(05):1222–1226. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000241098.11583.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charoenkwan K. Effective use of the Bakri postpartum balloon for posthysterectomy pelvic floor hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(06):5860–586000. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaya B, Tuten A, Daglar K et al. Balloon tamponade for the management of postpartum uterine hemorrhage. J Perinat Med. 2014;42(06):745–753. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2013-0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vrachnis N, Salakos N, Iavazzo C et al. Bakri balloon tamponade for the management of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122(03):265–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berg C J, Harper M A, Atkinson S M et al. Preventability of pregnancy-related deaths: results of a state-wide review. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(06):1228–1234. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000187894.71913.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]