Abstract

Study Design

Prospective cohort study.

Objective

To identify associations of spondylotic and kinematic changes with low back pain (LBP).

Summary of Background Data

The ability to characterize and differentiate the biomechanics of both the symptomatic and asymptomatic lumbar spine is crucial to alleviate the sparse literature on the association of lumbar spine biomechanics and LBP.

Methods

Lumbar dynamic plain radiographs (flexion-extension), dynamic CT scanning (axial rotation, disc height) and MRI (disc and facet degeneration grades) were obtained for each subject. These parameters were compared between symptomatic and control groups using Student’s t-test and multivariate logistic regression, which controlled for patient age and sex and identified spinal parameters that were independently associated with symptomatic LBP. Disc grade and mean segmental motion by level were tested by one-way ANOVA.

Results

Ninety-nine volunteers (64 asymptomatic/35 LBP) were prospectively recruited. Mean age was 37.3±10.1 y.o. and 55% were male. LBP showed association with increased L5/S1 translation (odds ratio [OR] 1.63 per mm, p=0.005), decreased flexion-extension motion at L1/L2 (OR 0.87 per degree, p=0.036), L2/L3 (OR 0.88 per degree, p=0.036), and L4/L5 (OR 0.87 per degree, p=0.020), increased axial rotation at L4/L5 (OR 2.11 per degree, p=0.032), decreased disc height at L3/L4 (OR 0.52 per mm, p=0.008) and L4/L5 (OR 0.37 per mm, p<0.001), increased disc grade at all levels (ORs 2.01–12.33 per grade, p=0.001–0.026), and increased facet grade at L4/L5 (OR 4.99 per grade, p=0.001) and L5/S1 (OR 3.52 per grade, p=0.004). Significant associations were found between disc grade and kinematic parameters (flexion-extension motion, axial rotation, and translation) at L4/L5 (p=0.001) and L5/S1 (p<0.001), but not at other levels (p>0.05).

Conclusions

In symptomatic individuals, L4/L5 and L5/S1 levels were affected by spondylosis and kinematic changes. This study clarifies the relationships between kinematic alterations and LBP, mostly observed at the above-mentioned segments.

Keywords: Low Back Pain, Spinal Instability, Flexion-extension, Axial Rotation, Disc Degeneration, Spine Degeneration, Aging, Spondylosis, Spine Kinematics, CT 3D-Models

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the major reasons for seeking medical care1–6 and it is estimated that over 80% of the population will experience LBP within their lifetime.7 Due to its prevalence, treatment and care for LBP is estimated to cost around $50 billion dollars per year in the United States alone.8,9 Non-radicular back pain (LBP) is more common and less well understood than radicular pain, i.e., sciatica.10 Lumbar disc disease is cited as the most common etiology of persistent back pain and sciatica; however, many individuals with apparent disc disease on magnetic resonance (MR) images are asymptomatic. Segmental instability of the lumbar spine is another common cause of LBP but the anatomic changes in the intervertebral disc, vertebral body, and facet joints associated with instability are not clearly known. Because of these unknown variables, results of treatment are often unpredictable and the efficacy of different treatment modalities is difficult to assess. Exploring biomechanical characteristics of the symptomatic lumbar spine is necessary in order to better target and evaluate treatments for LBP.

While previous studies have found associations between LBP and biomechanical properties of the lumbar spine, including facet angle, intervertebral disc degeneration and axial rotation, the available literature is generally limited by inaccurate measurement of segmental motion in vivo, small sample sizes, and lack of appropriate control subjects matched by age and gender.11–16 Further, there are conflicting reports regarding certain spinal characteristics, such as facet angle, 13,17,18 facet joint space area,12,19,20 and axial rotational movement.21–23

In order to address the current limitations in the literature, the present study aims to use a large, prospective cohort of asymptomatic controls and patients with LBP to identify biomechanical characteristics associated with the development of LBP. This information will be useful in the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar spine pathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Selection

The local Institutional Review Board approved this study and all enrolled subjects provided informed consent. Both asymptomatic individuals and patients with LBP were recruited, aged 20 to 60 years. The inclusion criteria for patients with LBP includes recurrent pain in the low back with at least two episodes of at least 6 weeks brought on by modest physical exertion. Exclusions include prior surgery for back pain, contraindications to MR, severe osteoporosis, or severe disc collapse at multiple levels. Other exclusion criteria include evidence of severe central or spinal stenosis, destructive process involving the spine, litigation or compensation proceedings, extreme obesity (body mass index greater than or equal to 40 kilograms per meter squared), congenital spine defect, previous spinal injury, or claustrophobia.

For asymptomatic individuals, exclusion criteria included current low back pain, previous spinal surgery, history of LBP, obesity, claustrophobia or other contraindications to MR and computed tomography (CT) imaging such as presence of a pacemaker, metallic implants, etc.

A power analysis was performed a priori and found that 64 subjects would be required to have 80% power to detect differences between means greater than 1.5 times the average of the standard deviations of the two populations.

qCT-based Bone Mineral Density Analysis

The CT data was employed determined a true volumetric measurement of the bone mineral density (BMD, g/cm3) at the L3 level24,25 using a quantitative-CT (qCT) routine implemented in the Mimics medical image post-processing environment (Mimics, Materialise Corp., Leuven, Belgium).

Imaging

For each subject, lumbar dynamic flexion/extension plain radiographs were obtained in the lateral decubitus position. Next, MR imaging was obtained for each subject. A 1.5-T MR unit (Signa, GE Medical Systems) was used to obtain 3.0 mm thick axial (proton density) and sagittal (T2-weighted) images. T2 weighted sagittal MR images were used to evaluate the disc degeneration in five grades (grade 1: normal – grade 5: advanced degeneration) using Pfirmmann’s grading scheme.26 Proton density axial images were used to assess the degenerative changes of the facet joints (facet grade) in terms of cartilage degeneration, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophyte formation according to the classification suggested by Fujiwara et al.27

Intervertebral translation and flexion-extension angular range of motion were measured using the planar X-ray films. Each subject underwent dynamic flexion-extension radiographic examination. Flexion-extension radiographs were taken in the lateral decubitus position to eliminate the effect of gravity and elicit less pain during the examination. Each subject was instructed to make and maintain a full flexion (or extension) as much as the subject was able to while the radiographs were taken. The flexion-extension radiographs were scanned and stored in digitized form. Segmental rotatory and translational motions were measured using a custom software program.28 In order to obtain precise and well-contrasted images, a Region of Interest (ROI) was set at each intervertebral level interactively on the computer screen and enlarged 400% using a bilinear-interpolation, size-conversion algorithm.29 The most anterior and posterior margins of the vertebral endplates were digitized interactively on the computer screen to calculate flexion/extension motion and antero-posterior translation. The antero-posterior width of the L3 at the mid-vertebral body was also measured and calibrated by the width measured by the 3D CT model at the same location in order to calculate the absolute antero-posterior translation in millimeters.

Dynamic CT imaging was subsequently obtained for each subject (Volume Zoom, Siemens, Malvern, PA, tube voltage: 120 kV, tube current: 100 mAs, field of view: approximately 200 mm, image matrix: 512×512, slice increment: 1.0 mm, slice thickness: 1.0 mm). The subjects were placed in a body restraint and loading apparatus in the supine position in the gantry of the CT scanner. The subject’s torso, pelvis, and thighs were held using custom made hip and chest restraints, allowing lumbar spine movements while preventing hip and sacroiliac joint rotation.30 The lumbar spine was axially rotated externally and passively by spinning the chest using a specially designed apparatus. The subjects were told to limit voluntary muscle activity during testing. CT images of the twisted lumbar spine were obtained at a maximum rotation angle of 50° to the left and right.30,31 The CT data were post-processed (Mimics, Materialise Corp., Leuven, Belgium) to obtain point cloud 3D models of the lumbar spine (L1-S1) that were subsequently used to determine the axial rotation angular range of motion and the corresponding intervertebral disc height distribution.30,31

The measurement method of the axial rotation was fully described previously elsewhere30,31 and will be described briefly here. The axial rotations were measured using the 3D CT models by a validated custom made 3D-3D registration algorithm (the volume merge method). In the volume merge method, a vertebral body in the neutral position (the moving vertebra) was virtually rotated and translated toward the same body in a rotated position (the stationary target). The rotations were performed in a sequence of axial rotation, lateral bending and flexion/extension about fixed axes determined by CT coordinates. These rotations and translations of the vertebral body were conducted in 0.1° and 0.1 mm increments, respectively, until the moving vertebra merged with the stationary target in the rotated position. An isotropic voxel with a dimension of 1.0 mm was created for each point of the stationary target. The number of these voxels with the points of the moving vertebra was normalized by the number of the entire voxels, and used as the degree of volume merging. The degree of volume merging was maximized in real-time through rotation or translation of the moving vertebra. The accuracy of the volume-merge method is reported 0.1 mm in translation and 0.2° in rotation.30 Segmental rotations for each motion segment were calculated by Euler angles with a sequence of axial rotation, lateral bending and flexion/extension and the axial rotation angular range of motion was determined by the axial rotational angle.32

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata® version 13.1 (StataCorp, LP, College Station, Texas, USA). All tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was established at a two-sided α level of 0.05 (p<0.05).

Spinal parameters were compared between asymptomatic volunteers and patients with symptomatic LBP using Student’s t-test and multivariate logistic regression. Multivariate regression controlled for patient age and sex and identified spinal parameters that were independently associated with symptomatic LBP. For parameters significant on multivariate analysis, the predicted probability of LBP was calculated and plotted for each unit increase in the corresponding variable. In addition, to explore associations between spondylotic changes and kinematic changes, the association between disc grade and mean segmental motion by level were plotted and tested by analysis of variance (ANOVA). One-way ANOVA was used to perform comparisons of disc grade (independent variable) and individual kinematic parameters (dependent variables) at each motion segment level, while multivariate ANOVA was used to test the association of disc grade and all three kinematic parameters concurrently at each motion segment level. F tests were performed and p-values from these tests were reported. For analysis, age was binned into a categorical variable as is common when including age in a multivariate analysis.33

RESULTS

A total of 99 volunteers (64 asymptomatic individuals and 35 patients with LBP patients) were recruited for this study. Mean age was 37.3±10.1 years old and 55.6% were male. Differences between individuals with and without LBP are reported in Table 1. Patients with LBP were generally older (p=0.036), however groups did not differ by sex (p=0.814). As expected, a decrease in BMD was verified by age; however both asymptomatic/symptomatic and gender comparisons did not show significant differences (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patient sample.

| Demographics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients | Asymptomatic | Symptomatic | P | |

| Overall | 99 (100%) | 64 (64.6%) | 35 (35.4%) | |

| Age group | 0.036 | |||

| 20–29 years | 25 (25.3%) | 20 (31.3%) | 5 (14.3%) | |

| 30–39 years | 35 (35.4%) | 20 (31.3%) | 15 (42.9%) | |

| 40–49 years | 24 (24.2%) | 18 (28.1%) | 6 (17.1%) | |

| 50–59 years | 15 (15.2%) | 6 (9.4%) | 9 (25.7%) | |

| Male sex | 55 (55.6%) | 35 (54.7%) | 20 (57.1%) | 0.814 |

| Volumetric Bone Mineral Density (g/cm3) – Mean (SD) | ||||

| All Patients | Asymptomatic | Symptomatic |

P (Symptomatic Vs. Control) |

|

| Age group | ||||

| 20–29 years | 315.3 (49.1)*; **; ***; | 308.6 (54.8) | 335.6 (18.0) | .3599 |

| 30–39 years | 281.2 (44.0) !; !! | 287.0 (29.0) | 275.8 (55.1) | .5547 |

| 40–49 years | 275.1 (46.0) § | 282.9 (51.2) | 259.5 (30.9) | .2837 |

| 50–59 years | 234.6 (49.6) | 240.5 (58.0) | 231.4 (47.8) | .7558 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 275.5 (42.3) | 280.7 (43.5) | 268.6 (40.9) | .3945 |

| Female | 280.6 (61.8) | 291.8 (57.7) | 265.9 (65.7) | .2096 |

Notes For the BMD data: 1) Symbols denote significant differences (p< 0.05) between the following pairs:

20s vs. 30s;

20s vs. 40s;

20 vs. 50s;

30s vs. 40s;

30s vs. 50s;

40s vs. 50s.

2) No differences by gender.

Symptomatic and asymptomatic patients were subsequently compared in terms of intervertebral translation, flexion-extension angular range of motion, axial range of motion, disc height, disc grade, and facet grade using Student’s t-test. Multivariate logistic regression was next used to compare cohorts while controlling for patient age and sex. The results of these analyses are reported in Table 2. In this table, the odds ratios represent the odds of LBP given a one-unit increase in the specified measurement.

Table 2.

Differences between asymptomatic and symptomatic patients, by spinal measurement and level.

| Measurement | Asymptomatic (mean) |

Symptomatic (mean) |

T-test |

Multivariate logistic regression |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | Odds Ratio | p | |||

| Translation (mm) | |||||

| L1/L2 | 1.03 | 1.18 | 0.979 | 1.10 | 0.559 |

| L2/L3 | 1.55 | 1.02 | 0.061 | 0.83 | 0.194 |

| L3/L4 | 1.20 | 1.80 | 0.181 | 1.30 | 0.112 |

| L4/L5 | 1.86 | 1.35 | 0.081 | 0.79 | 0.163 |

| L5/S1 | 0.81 | 1.60 | 0.057 | 1.63 | 0.005 |

| Flexion/Extension Motion (degrees) |

|||||

| L1/L2 | 6.30 | 4.48 | 0.004 | 0.87 | 0.036 |

| L2/L3 | 8.51 | 5.41 | 0.003 | 0.88 | 0.036 |

| L3/L4 | 10.67 | 7.60 | 0.424 | 0.99 | 0.550 |

| L4/L5 | 12.09 | 9.20 | <0.001 | 0.87 | 0.020 |

| L5/S1 | 9.35 | 8.01 | 0.297 | 0.99 | 0.668 |

| Axial rotation (degrees) | |||||

| L1/L2 | 1.97 | 2.21 | 0.544 | 1.05 | 0.670 |

| L2/L3 | 2.32 | 2.13 | 0.237 | 0.59 | 0.120 |

| L3/L4 | 1.82 | 2.10 | 0.075 | 1.88 | 0.063 |

| L4/L5 | 1.55 | 1.86 | 0.036 | 2.11 | 0.032 |

| L5/S1 | 1.86 | 1.44 | 0.082 | 0.78 | 0.379 |

| Disc height (mm) | |||||

| L1/L2 | 6.34 | 5.97 | 0.119 | 0.66 | 0.092 |

| L2/L3 | 7.56 | 7.02 | 0.017 | 0.55 | 0.028 |

| L3/L4 | 8.30 | 7.56 | 0.004 | 0.52 | 0.008 |

| L4/L5 | 8.51 | 6.91 | <0.001 | 0.37 | <0.001 |

| L5/S1 | 6.56 | 5.78 | 0.041 | 0.77 | 0.104 |

| Disc grade | |||||

| L1/L2 | 2.44 | 3.00 | 0.002 | 2.01 | 0.026 |

| L2/L3 | 2.61 | 3.22 | <0.001 | 3.91 | 0.002 |

| L3/L4 | 2.58 | 3.42 | <0.001 | 12.33 | <0.001 |

| L4/L5 | 2.82 | 3.71 | <0.001 | 8.48 | <0.001 |

| L5/S1 | 3.26 | 3.85 | <0.001 | 3.81 | 0.001 |

| Facet grade | |||||

| L1/L2 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 0.313 | 1.78 | 0.241 |

| L2/L3 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.722 | 0.78 | 0.615 |

| L3/L4 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.804 | 0.60 | 0.307 |

| L4/L5 | 0.60 | 1.19 | <0.001 | 4.99 | 0.001 |

| L5/S1 | 0.73 | 1.29 | <0.001 | 3.52 | 0.004 |

Bolding indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05). Odds ratios represent odds of symptomatic back pain for each one-unit increase in each parameter.

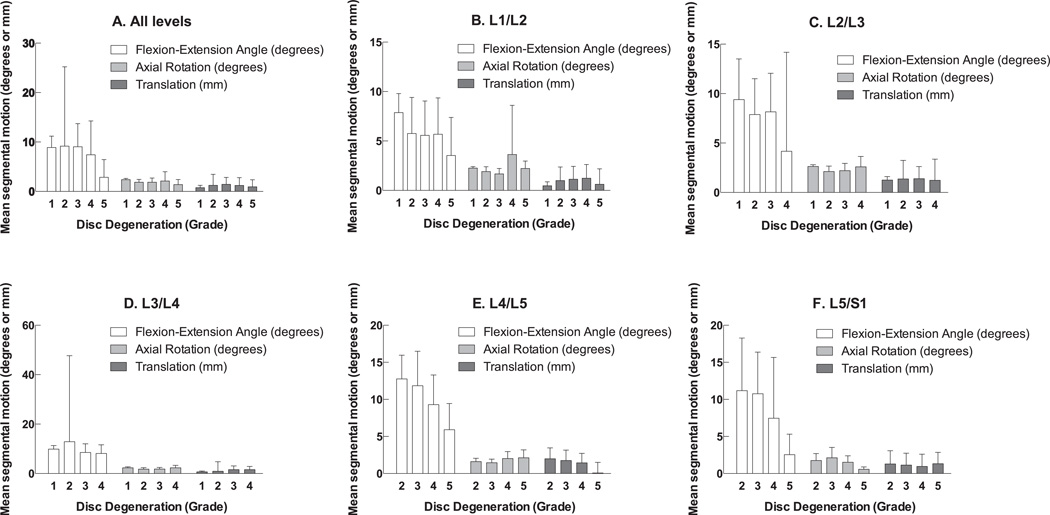

Low back pain was found to be associated with increased L5/S1 translation (odds ratio [OR] 1.63 per mm, p=0.005), decreased flexion/extension motion at L1/L2 (OR 0.87 per degree, p=0.036), L2/L3 (OR 0.88 per degree, p=0.036), and L4/L5 (OR 0.87 per degree, p=0.020), increased axial rotation at L4/L5 (OR 2.11 per degree, p=0.032), decreased disc height at L3/L4 (OR 0.52 per mm, p=0.008) and L4/L5 (OR 0.37 per mm, p<0.001), increased disc grade at all levels (ORs 2.01–12.33 per grade, p=0.001–0.026), and increased facet grade at L4/L5 (OR 4.99 per grade, p=0.001) and L5/S1 (OR 3.52 per grade, p=0.004). Figure 1 shows the average segmental motion at each disc grade for all levels (A), and for each level individually (B-F). ANOVA found significant association between disc grade and kinematic parameters (flexion/extension motion, axial rotation, and translation) at L4/L5 (p=0.001) and L5/S1 (p<0.001), but not at other levels (p>0.05).

Figure 1.

Association of disc grade with mean segmental motion, by motion segment level.

Using one-way ANOVA to perform comparisons of disc grade and individual kinematic parameters at each motion segment level, several additional associations were found (Table 3). At L2/L3, disc grade was associated with flexion-extension motion (p=0.019). At L3/L4, disc grade was associated with axial rotation (p=0.040). At L4/L5, disc grade was associated with flexion-extension motion (p=0.003) and axial rotation (p=0.002). Similarly, at L5/S1, disc grade was also associated with flexion-extension motion (p=0.019) and axial rotation (p=0.003).

Table 3.

Results of analysis of variance for association of disc grade with translation, flexion/extension motion, and axial rotation, by motion segment level.

| Level | Overall | Translation | Flexion-extension motion |

Axial rotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | p | p | p | |

| L1/L2 | 0.144 | 0.856 | 0.688 | 0.025 |

| L2/L3 | 0.158 | 0.955 | 0.019 | 0.193 |

| L3/L4 | 0.397 | 0.810 | 0.839 | 0.040 |

| L4/L5 | <0.001 | 0.120 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| L5/S1 | <0.001 | 0.897 | 0.019 | 0.003 |

DISCUSSION

Low back pain is a challenging condition which incurs large costs on the healthcare system, yet the specific pathomechanics associated with LBP remains poorly understood.1–4,7–9,34 In order to inform the treatment and prevention of LBP, the present study aimed to identify biomechanical characteristics associated with LBP in a large, prospective cohort of asymptomatic controls and patients with LBP. This study found that low back pain was associated with increased L5/S1 translation, decreased flexion/extension angle at L1/L2, L2/L3, and L4/L5, increased axial rotation at L4/L5, decreased disc height at L3/L4 and L4/L5, increased disc grade at all levels, and increased facet grade at L4/L5 and L5/S1.

In terms of kinematics, it is notable that symptomatic patients demonstrated increased axial rotation at L4/L5 (p=0.036), decreased flexion-extension angular motion at L1/L2 (p=0.004), L2/L3 (p=0.003), and L4/L5 (p<0.001); as well as a trend in increased translational motion at L5/S1 (p=0.057) in our testing (Table 2). Distinct spinal motion abnormalities have been correlated with LBP,23,35–44 but the precise kinematics have not been fully elucidated. The finding of increased axial rotation and increased translation in the symptomatic patients corroborates prior investigators who correlated excessive lumbar motion with LBP.40 However, other investigators have demonstrated decreased motion in patients with LBP which supports our finding of decreased angular motion in the symptomatic cohort.35,39

Patients with LBP also had significantly different markers of spondylosis when compared to asymptomatic controls. The L4/5 motion segment had decreased disc height, increased disc grade, and increased facet grade. The L5/S1 segment had increased disc grade and increased facet grades. These results support the available literature which consistently links degenerative disc disease and disc height loss with LBP.45–47 Considerable debate, however, surrounds the association of facet joint degeneration and back pain.48–50 There are very few high quality studies investigating this link and many do not take advantage of advanced imaging modalities such as CT in their assessment of facet joint arthrosis which limits the assessment. In our investigation, we used CT, MRI and subject-specific 3D models to assess the facet joints between patients with and without back pain and noted a significant correlation between facet grade and back pain. Additionally, our findings showing that the lower lumbar segments are involved more commonly support the results from other reports in the literature about facet joints of the most caudal segments being the ones affected the most.27,49

It is clear in the literature that degenerative changes in the lumbar spine are linked with abnormal kinematics, which echoes the findings of the current study. Kirkaldy-Willis proposed a theory of increasing instability with degenerative changes up to a point where advanced degenerative changes cause restabilization.51 More recently, Kong et al. performed a kinematic analysis and demonstrated increasing degrees of translational motion and decreasing angular motion with advancing degenerative changes in the lumbar spine.52 In our study, significant spondylotic changes at L4/L5 and L5/S1 were associated with differences in observed motion characteristics. Interestingly, Hayashi et al. have postulated that Modic changes53,54 may confer unique changes on the stability of the spine independently of other degenerative changes.55 We did not specifically evaluate Modic changes in our investigation but perhaps this too could explain the differences we observed. Finally, at L5/S1, there may have been greater translational motion observed in the symptomatic cohort because this tends to be a more inherently stable segment and so any instability likely represents pathology and manifests as pain. Instability is thus a very sensitive marker of pain in this setting. Additionally, this motion may reflect increased stresses experienced at this level as motion segments above go through the process of degeneration.

A unique finding of this investigation was indeed the preferential involvement of the lower lumbar segments in terms of both pathokinematic and spondylotic changes. This is commonly observed clinically and well-documented.27 The pathomechanics of this process are poorly understood but are likely related to the rather distinct mechanical scenario encountered at the lower lumbar levels which involves shear loads and altered axial load transmission. Clinical biomechanical investigations have demonstrated kinematic differences in lumbar motion depending on the level examined with greater disturbances seen in the lower levels.56,57 As previously discussed, facet joint arthritis was seen more commonly at the caudal spinal segments.27,49 This stress likely concentrates to an even greater degree at the L4/L5 segment. As explained by Fujiwara et al., the L4/L5 segment is more commonly involved because of the relative hypermobility of this segment adjacent to a relatively stiff L5/S1 segment.27 This would explain the multiple kinematic and spondylotic changes seen at this level in the present study.

Investigations into adjacent segment disease and post-lumbar fusion motion characteristics support this stress related theory (L3, L4, and L5).58 Lao et al. used kinetic MRI to evaluate lumbar kinematics associated with degenerative disc disease and they found that with advancing disc degeneration the lumbar segments L2/L3 and L3/L4 had significant decreases in angular motion while L4/L5 retained its degree of mobility.59,60 These findings support the regional differences which we observed in our LBP cohort. The evolution of these regional differences in the pathomechanics of the lumbar spine likely reaches a threshold where the degree of degeneration and motion at the lower levels becomes symptomatic. Developing a quantitative marker for when this balance is tipped was not evaluated in this study, but warrants clinical investigation.

This study is not without limitations. The first limitation is that long-term outcome data is not available for this cohort of patients. In addition, while the a priori power analysis indicated that the sample size for this study was appropriate, additional patients would allow for sub-group analyses that would better characterize the effects of specific biomechanical parameters on LBP. As seen in Figure 1, for certain grades of disc degeneration at each level, there were larger standard error values. This was determined to be due to lower numbers of patients at with these grades of degeneration at different levels, rather than the presence of outliers.

The lumbar segmental motions were measured in the supine position without axial loading in the present study. Previous studies using kinematic MR scanning demonstrated the validity of lumbar kinematics under weight-bearing.52,61 These measurements of spinal instability under physiological loading conditions may provide clearer relationships between lumbar instability and LBP.

The results of this study have significant implications for clinical practice and future research into LBP. Unlike radicular pain, it is often difficult to clinically localize non-radicular LBP to a specific pathologic level, particularly in patients with changes at multiple levels. The strength of the present study was the ability to use multivariate analysis to identify spondylotic and kinematic changes, stratified by level, that were independently associated with non-radicular LBP compared to asymptomatic controls. These spondylotic and kinematic changes represent potential targets for future research and treatments.

Research into identifying precise markers of degeneration and instability that would result in LBP is warranted. Future investigations could also focus on correlating kinematic changes in the lumbar spine of symptomatic patients to better identify the pathologic level and allow for guided treatments. Moreover, research and development of motion preservation devices should look into the different kinematics at different levels.

This study is the first of its kind to prospectively investigate the kinematic and spondylotic differences between symptomatic LBP patients and asymptomatic controls. We demonstrated significant differences in both parameters between symptomatic and asymptomatic cohorts. This study provides important insight on the differences between patients with and without LBP. Further investigations into the clinical correlations of these findings will hopefully aid clinicians in their ability to diagnose and treat patients with LBP.

Acknowledgments

NIH grants NIAMS P01-AR48152 and NCCIH R01-AT006692 funds were received in support of this work.

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: grants, royalties, stocks.

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: N/A

References

- 1.Andersson GB. Epidemiology of low back pain. Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 1998;281:28–31. doi: 10.1080/17453674.1998.11744790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet (London, England) 1999;354:581–585. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crow WT, Willis DR. Estimating cost of care for patients with acute low back pain: a retrospective review of patient records. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2009;109:229–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2008;8:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinnott PL, Siroka AM, Shane AC, et al. Identifying neck and back pain in administrative data: defining the right cohort. Spine. 2012;37:860–874. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182376508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (London, England) 2012;380:2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP, et al. The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Archives of internal medicine. 2009;169:251–258. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2006;88(Suppl 2):21–24. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pai S, Sundaram LJ. Low back pain: an economic assessment in the United States. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2004;35:1–5. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(03)00101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aprill C, Bogduk N. High-intensity zone: a diagnostic sign of painful lumbar disc on magnetic resonance imaging. The British journal of radiology. 1992;65:361–369. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-65-773-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasegawa K, Shimoda H, Kitahara K, et al. What are the reliable radiological indicators of lumbar segmental instability? The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2011;93:650–657. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B5.25520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otsuka Y, An HS, Ochia RS, et al. In vivo measurement of lumbar facet joint area in asymptomatic and chronic low back pain subjects. Spine. 2010;35:924–928. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c9fc04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pichaisak W, Chotiyarnwong C, Chotiyarnwong P. Facet joint orientation and tropism in lumbar degenerative disc disease and spondylolisthesis. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet. 2015;98:373–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siemionow K, An H, Masuda K, et al. The effects of age, sex, ethnicity, and spinal level on the rate of intervertebral disc degeneration: a review of 1712 intervertebral discs. Spine. 2011;36:1333–1339. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f2a177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suri P, Hunter DJ, Rainville J, et al. Presence and extent of severe facet joint osteoarthritis are associated with back pain in older adults. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2013;21:1199–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang S, Liu H, Zhang Y. Spinous process deviation and disc degeneration in lumbosacral segment. The Journal of surgical research. 2015;193:713–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boden SD, Riew KD, Yamaguchi K, et al. Orientation of the lumbar facet joints: association with degenerative disc disease. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1996;78:403–411. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199603000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noren R, Trafimow J, Andersson GB, et al. The role of facet joint tropism and facet angle in disc degeneration. Spine. 1991;16:530–532. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panjabi MM, Goel V, Oxland T, et al. Human lumbar vertebrae. Quantitative three-dimensional anatomy. Spine. 1992;17:299–306. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199203000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon P, Espinoza Orias AA, Andersson GB, et al. In vivo topographic analysis of lumbar facet joint space width distribution in healthy and symptomatic subjects. Spine. 2012;37:1058–1064. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182552ec9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams MA, Hutton WC. The relevance of torsion to the mechanical derangement of the lumbar spine. Spine. 1981;6:241–248. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198105000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farfan HF, Cossette JW, Robertson GH, et al. The effects of torsion on the lumbar intervertebral joints: the role of torsion in the production of disc degeneration. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1970;52:468–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujiwara A, Lim TH, An HS, et al. The effect of disc degeneration and facet joint osteoarthritis on the segmental flexibility of the lumbar spine. Spine. 2000;25:3036–3044. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lochmuller EM, Burklein D, Kuhn V, et al. Mechanical strength of the thoracolumbar spine in the elderly: prediction from in situ dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, quantitative computed tomography (QCT), upper and lower limb peripheral QCT, and quantitative ultrasound. Bone. 2002;31:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00792-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taton G, Rokita E, Wrobel A, et al. Combining areal DXA bone mineral density and vertebrae postero-anterior width improves the prediction of vertebral strength. Skeletal radiology. 2013;42:1717–1725. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1723-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, et al. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine. 2001;26:1873–1878. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200109010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujiwara A, Tamai K, Yamato M, et al. The relationship between facet joint osteoarthritis and disc degeneration of the lumbar spine: an MRI study. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 1999;8:396–401. doi: 10.1007/s005860050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akeda K, Yamada T, Inoue N, et al. Risk factors for lumbar intervertebral disc height narrowing: a population-based longitudinal study in the elderly. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2015;16:344. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0798-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duan CY, Espinoza Orias AA, Shott S, et al. In vivo measurement of the subchondral bone thickness of lumbar facet joint using magnetic resonance imaging. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2011;19:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ochia RS, Inoue N, Renner SM, et al. Three-dimensional in vivo measurement of lumbar spine segmental motion. Spine. 2006;31:2073–2078. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000231435.55842.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ochia RS, Inoue N, Takatori R, et al. In vivo measurements of lumbar segmental motion during axial rotation in asymptomatic and chronic low back pain male subjects. Spine. 2007;32:1394–1399. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318060122b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crawford NR, Yamaguchi GT, Dickman CA. Methods for determining spinal flexion/extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation from marker coordinate data: Analysis and refinement. Hum Mov Sci. 1996;15:55–78. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basques BA, Toy JO, Bohl DD, et al. General compared with spinal anesthesia for total hip arthroplasty. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2015;97:455–461. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue N, Espinoza Orias AA. Biomechanics of intervertebral disk degeneration. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2011;42:487–499. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dvorak J, Panjabi MM, Grob D, et al. Clinical validation of functional flexion/extension radiographs of the cervical spine. Spine. 1993;18:120–127. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199301000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farfan HF, Gracovetsky S. The nature of instability. Spine. 1984;9:714–719. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198410000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frymoyer JW, Newberg A, Pope MH, et al. Spine radiographs in patients with low-back pain. An epidemiological study in men. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1984;66:1048–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gertzbein SD, Seligman J, Holtby R, et al. Centrode patterns and segmental instability in degenerative disc disease. Spine. 1985;10:257–261. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198504000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gracovetsky S, Newman N, Pawlowsky M, et al. A database for estimating normal spinal motion derived from noninvasive measurements. Spine. 1995;20:1036–1046. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199505000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayes MA, Howard TC, Gruel CR, et al. Roentgenographic evaluation of lumbar spine flexion-extension in asymptomatic individuals. Spine. 1989;14:327–331. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198903000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan FP, King T. Primary instability of lumbar vertebrae as a common cause of low back pain. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1957;39-b:6–22. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.39B1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nachemson A. Lumbar spine instability. A critical update and symposium summary. Spine. 1985;10:290–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pope MH, Panjabi M. Biomechanical definitions of spinal instability. Spine. 1985;10:255–256. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198504000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stokes IA, Frymoyer JW. Segmental motion and instability. Spine. 1987;12:688–691. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198709000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Schepper EI, Damen J, van Meurs JB, et al. The association between lumbar disc degeneration and low back pain: the influence of age, gender, and individual radiographic features. Spine. 2010;35:531–536. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181aa5b33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goode AP, Carey TS, Jordan JM. Low back pain and lumbar spine osteoarthritis: how are they related? Current rheumatology reports. 2013;15:305. doi: 10.1007/s11926-012-0305-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pye SR, Reid DM, Smith R, et al. Radiographic features of lumbar disc degeneration and self-reported back pain. The Journal of rheumatology. 2004;31:753–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butler D, Trafimow JH, Andersson GB, et al. Discs degenerate before facets. Spine. 1990;15:111–113. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199002000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalichman L, Hunter DJ. Lumbar facet joint osteoarthritis: a review. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2007;37:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewinnek GE, Warfield CA. Facet joint degeneration as a cause of low back pain. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1986:216–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Farfan HF. Instability of the lumbar spine. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1982:110–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kong MH, Morishita Y, He W, et al. Lumbar segmental mobility according to the grade of the disc, the facet joint, the muscle, and the ligament pathology by using kinetic magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 2009;34:2537–2544. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b353ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Modic MT, Masaryk TJ, Ross JS, et al. Imaging of degenerative disk disease. Radiology. 1988;168:177–186. doi: 10.1148/radiology.168.1.3289089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Modic MT, Steinberg PM, Ross JS, et al. Degenerative disk disease: assessment of changes in vertebral body marrow with MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;166:193–199. doi: 10.1148/radiology.166.1.3336678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hayashi T, Daubs MD, Suzuki A, et al. Motion characteristics and related factors of Modic changes in the lumbar spine. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2015;22:511–517. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.SPINE14496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gombatto SP, Brock T, DeLork A, et al. Lumbar spine kinematics during walking in people with and people without low back pain. Gait & posture. 2015;42:539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mitchell T, O'Sullivan PB, Burnett AF, et al. Regional differences in lumbar spinal posture and the influence of low back pain. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2008;9:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Okuda S, Iwasaki M, Miyauchi A, et al. Risk factors for adjacent segment degeneration after PLIF. Spine. 2004;29:1535–1540. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000131417.93637.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lao L, Daubs MD, Scott TP, et al. Effect of disc degeneration on lumbar segmental mobility analyzed by kinetic magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 2015;40:316–322. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Radcliff KE, Kepler CK, Jakoi A, et al. Adjacent segment disease in the lumbar spine following different treatment interventions. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2013;13:1339–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tan Y, Aghdasi BG, Montgomery SR, et al. Kinetic magnetic resonance imaging analysis of lumbar segmental mobility in patients without significant spondylosis. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2012;21:2673–2679. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2387-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]