Abstract

CRISPR-Cas9 screens are powerful tools for high-throughput interrogation of genome function, but can be confounded by nuclease-induced toxicity at both on- and off-target sites, likely due to DNA damage. Here, to test potential solutions to this issue, we design and analyse a CRISPR-Cas9 library with 10 variable-length guides per gene and thousands of negative controls targeting non-functional, non-genic regions (termed safe-targeting guides), in addition to non-targeting controls. We find this library has excellent performance in identifying genes affecting growth and sensitivity to the ricin toxin. The safe-targeting guides allow for proper control of toxicity from on-target DNA damage. Using this toxicity as a proxy to measure off-target cutting, we demonstrate with tens of thousands of guides both the nucleotide position-dependent sensitivity to single mismatches and the reduction of off-target cutting using truncated guides. Our results demonstrate a simple strategy for high-throughput evaluation of target specificity and nuclease toxicity in Cas9 screens.

CRISPR-Cas9 screens are powerful high-throughput tools but can be confounded by nuclease toxicity. Here the authors design a library of variable length gRNAs with thousands of negative controls, including the targeting of ‘safe' loci to account for on-target site DNA damage toxicity.

Genome-wide screens using the CRISPR-Cas9 system have been highly effective for determination of gene function1,2,3,4,5. While earlier RNA interference-based screening technologies have been highly effective6,7,8,9, they can suffer from low on-target efficacy, non-specific toxicity, and pervasive off-target effects10,11,12,13,14,15,16. The extent to which similar flaws also exist in Cas9 screens is under active investigation. Cas9 on-target efficacy is high, but the existence of in-frame indels can limit efficacy, as has been observed in large-scale screens1,10,17,18,19. The existence of non-specific toxicity resulting from Cas9 expression or nuclease activity has been previously proposed20,21 and more recently direct evidence has been found22,23 suggesting that this toxicity generates false-positives in screens for essential genes. Finally, although Cas9 off-target activity has been extensively investigated24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, it remains unresolved whether off-target effects confound results from large-scale screens.

Non-specific toxicity of reagents can affect interpretation of high-throughput screens. For example, shRNA overexpression can cause toxicity via misregulation of the endogenous miRNA processing machinery12. Non-targeting shRNAs have been used as negative controls to account for these effects, allowing accurate modelling of the null distribution and accurate hit calling15,16,33. Similarly, studies using Cas9 have included non-targeting single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs)22,23,34,35,36, which are overexpressed and loaded into Cas9, presumably controlling for the potentially disruptive binding of Cas9 to PAM sites throughout the genome30,37. However these non-targeting sgRNAs may fail to replicate the most dramatic, non-specific effect of Cas9 gene knockouts: the formation of double-strand breaks in genomic DNA22,23. In fact, cutting at amplified regions—where a single cut site results in numerous double-strand DNA breaks—has been found to be toxic across numerous cell lines22,23,36. Similarly, guides with large numbers of target sites have also been found to be toxic38.

Numerous strategies for reducing Cas9 off-target effects have been developed31, including paired nickases39, truncated guides32,40, FOKI dimer fusions41, and modifications to Cas9 itself42,43. Assays for genome-wide double-strand DNA breaks26,27,28,32 have indicated these strategies successfully limit off-target cutting. However, these experiments have so far been limited to measurement of the off-target cutting of a handful of guides, leaving open the question of how these off-targets may interfere with the output of high-throughput screens, and if the varied strategies for off-target reduction can be effective in this domain.

The use of truncated guides of length 17–18 bp has shown great promise in both reduction of off-targets and preservation of on-target activity32,40. Based on both low-throughput sequencing of candidate off-target sites40 and high-throughput determination of off-targets with GUIDE-seq for a handful of guides32, truncated guides appear to have fewer off-targets. Though reduced overall activity of truncated sgRNAs could be responsible for this reduction in off-target activity, low-throughput tests suggest that this is not the case in either human cell lines40 or yeast44.

Here we present results from a novel genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 deletion library in three cell lines. We demonstrate the existence of non-specific toxic effects from cutting on- and off-target sites and design a strategy to control for them. We take advantage of this toxicity to assay thousands of guides for off-target activity using growth as a phenotype. Using this system we can extract generalizable conclusions about off-target activity and provide evidence that truncated sgRNAs40 can improve specificity with little detectable loss in on-target activity in high-throughput screens.

Results

CRISPR deletion library

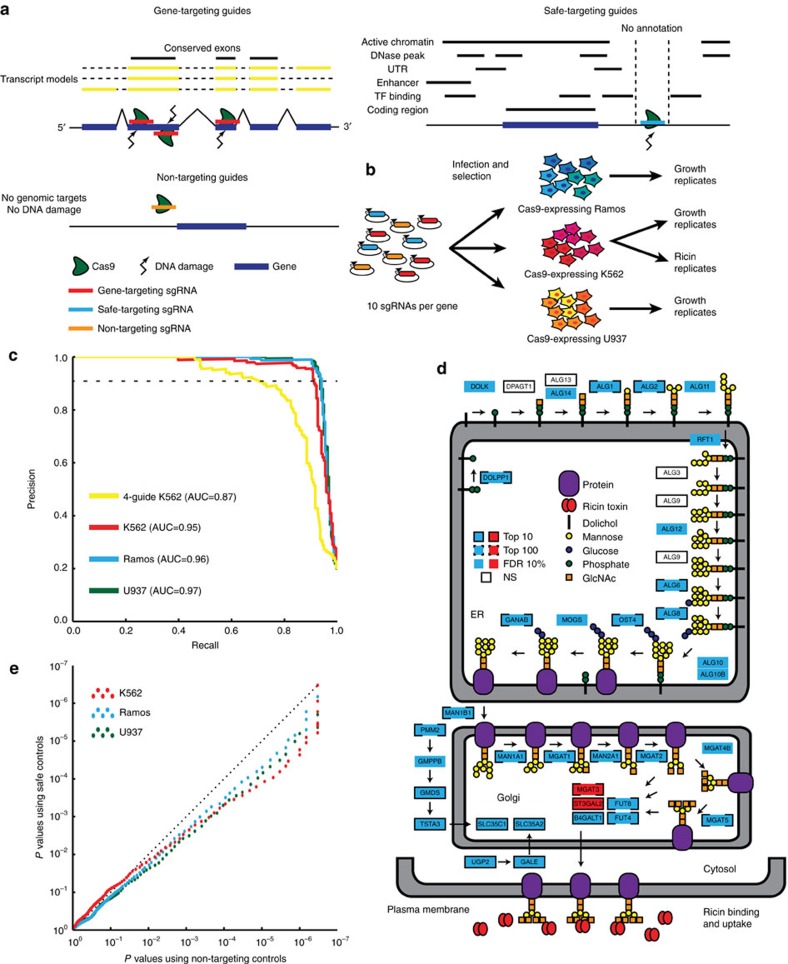

To evaluate the effects of nuclease toxicity and sgRNA length in genome-wide CRISPR screens, we designed a 10-sgRNA-per-gene CRISPR-Cas9 deletion library targeting all ∼20,500 protein-coding human genes (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Data 1; see methods for complete description). sgRNAs were chosen to balance (1) on-target potential to cause deleterious indels, as predicted by placement within the gene (Supplementary Fig. 1a), GC content (Supplementary Fig. 1b), and exon conservation (Supplementary Fig. 1c), and (2) off-target activity, as predicted by the number of 0-, 1- and 2-bp mismatch off-target sites (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). In order to determine the effect of sgRNA length, the library was designed to contain guides ranging from 17 to 20 bp in length (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Finally, to ensure multiple regions of the same gene were targeted, guides with overlapping target sites or targeting identical exons were avoided. To monitor the effect of nuclease-dependent toxicity, two distinct classes of negative controls were included: non-targeting controls with no binding sites in the genome and safe-targeting guides targeting genomic locations with no annotated function (Fig. 1a), discussed below. For ease of use, the library is synthesized as 9 sublibraries of functionally related genes (Supplementary Fig. 3a). A library targeting all ∼23,000 protein-coding mouse genes was designed using identical rules, but split into 20 distinct sublibraries to enable in vivo screens (Supplementary Data 2; Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Figure 1. Design and performance of Cas9 library.

(a) Schematic of library design indicating design of gene-targeting guides, safe-targeting guides, and non-targeting guides. (b) Growth screens were performed in duplicate in three cell lines, and a ricin screen was performed in duplicate in a single cell line. (c) Precision/recall curve for performance on gold-standard essential genes38. These curves graphically display the trade-off between the fraction of genes correctly identified as essential (precision) and the fraction of all essential genes identified (recall). Untreated conditions were compared to plasmid library composition and replicates were combined and analysed with casTLE20. Previous 4-guide duplicate screen in K562 included as reference20. (d) Schematic of nucleotide sugar and n-glycan synthesis genes in ricin screen results. Ricin treated conditions were compared to untreated conditions in K562, and replicates combined and analysed using casTLE20. Blue boxes indicate the gene knockout protected the cell from ricin while red boxes indicate the gene knockout sensitized the cell to ricin. NS indicates non-significance (q>0.1). White boxes indicate that these genes are known to be on-pathway but were not identified as ricin regulators. (e) Quantile-quantile plot showing altered distribution of P values using safe-targeting or non-targeting control in growth screens. P values are calculated from both replicates using casTLE20.

To validate the library, we infected Cas9-expressing K562, Ramos, and U937 human cell lines and grew replicate cultures to identify genes required for growth (Fig. 1b; see also Methods section). Library performance was evaluated using a previously defined set of gold-standard essential and nonessential genes38; these are predicted from expression or screen results to be either essential or nonessential for growth in all human cell lines. We find the results are highly reproducible (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c) and almost perfectly distinguish gold-standard essential and nonessential genes38 in each cell line (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Data 3 and 4). This greatly outperformed our previous Cas9 and shRNA library designs16,20,35, with >88% of gold-standard essential genes identified at 1% false positive rate versus the 60% identified by previous libraries.

To validate the library for screens other than growth, we performed a screen for modifiers of ricin toxicity in K562 cells in duplicate (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 4d; Supplementary Data 3 and 4), as we have extensive data on genes which modify this response16,33. While there are no gold-standard genes affecting ricin resistance, the screen with this library robustly identified genes involved in ricin resistance by several metrics. First, the screen identified known ricin regulators at 10% false discovery rate (FDR) including 32 of 48 genes validated from previous shRNA and CRISPRi screens33,45. 13 of the 16 genes not identified in this CRISPR screen are essential for growth (Supplementary Data 4) and would not be expected to be identified in a knockout screen. Beyond this, 895 genes were identified at 10% FDR, including a large number of genes which had not been previously implicated in ricin biology. Second, the newly identified genes included nearly every member of several interconnected nucleotide sugar and n-glycan synthesis pathways (Fig. 1d). These enzymes synthesize the cell surface β-linked Gal/GalNAc-containing glycans, which are bound by the ricin B-chain lectin and required for its uptake into the cell46,47. Effective identification of known and novel genes affecting ricin toxicity, as well as essential genes across three cell types, validate the presented CRISPR-Cas9 library as a robust tool for genome-wide screens.

Modelling non-specific toxicity with safe-targeting guides

To control for the potential effects of double-strand DNA breaks, we designed a set of guides targeting non-genic regions with no annotated function across 127 cell lines (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Data 5; and Methods section). These safe regions have no active chromatin marks, no experimentally or computationally determined transcription factor binding sites, no DNase accessibility signal, and are not conserved. Safe-targeting guides induce the same genomic DNA cutting as gene-targeting guides, as well as their overexpression and loading into Cas9, and therefore should theoretically provide better controls than non-targeting guides.

In all growth screens performed, we find safe-targeting sgRNAs are more toxic than their non-targeting counterparts, as measured by a relative depletion of the safe-targeting guides at late time points (Mann–Whitney test comparing safe-targeting to non-targeting guides; P value<10−26 for all replicates; Supplementary Fig. 5). The negative growth effect of safe-targeting guides is likely due to DNA damage and the subsequent repair response22,23. How this non-specific growth effect will affect phenotypes in all non-growth screens is less clear, but in our screen for genes affecting ricin toxicity in K562 cells (Fig. 1b), the use of non-targeting controls underestimates the true background noise as modelled by a distribution of safe-targeting sgRNAs (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test comparing safe-targeting guides to non-targeting guides; P value<10−7 for both replicates; Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). To test the impact of using safe-targeting guides for hit discovery, we examined the distribution of P values generated from the combination of replicates using casTLE20 with either the non-targeting controls only or the safe-targeting controls only. We find that using the non-targeting controls results in anti-conservative P values, that is, P values are more significant than when using safe-targeting controls, in our growth screens (Fig. 1e) and both overly conservative and anti-conservative tests in our ricin screen (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Anti-conservative P values can lead to false-positives as genes will appear more significant than they are, and conservative tests can lead to false-negatives as genes will appear less significant. A concrete example can be seen in an analysis of K562 growth data: at a 1% FDR cutoff, ∼2,100 genes with growth defects upon deletion are identified using the non-targeting controls, while ∼1,900 genes are identified using safe-targeting controls (Supplementary Data 6). This suggests safe-targeting controls can both prevent false-positive results in growth screens as well as more accurately determine significance in non-growth screens.

Detection of off-target toxicity

Having observed safe-targeting guide toxicity (Supplementary Fig. 5)—a growth effect independent of a gene effect—we investigated whether we could detect toxicity due to off-target cutting of gene-targeting sgRNAs (Supplementary Data 7). We found that when full-length (19–20 bp) guides have exact off-targets (0-mismatch off-targets) or 1-mismatch off-targets anywhere in the genome, they are more toxic than their counterparts without off-target matches (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 7). For full-length guides with 2-mismatch off-targets, a significant amount of toxicity is only observed for guides with 5+ off-target sites (Supplementary Fig. 8). Note that all guides were included in this analysis and that excluding guides targeting essential genes does not change these conclusions (Supplementary Fig. 9a,b).

Figure 2. Off-target detection using nuclease-induced toxicity.

(a) Median and quartile range of full-length 19 and 20 bp guides in three cell lines by number of 1-mismatch off-targets. P values are from a Mann–Whitney test compared to guides with 0 off-targets. (b) Single mismatches closer to the PAM are less tolerated. Guides with no perfect off-targets and exactly one 1-mismatch off-targets were stratified by the location of the mismatch. Those with the location of the mismatch farther from the PAM site display greater disenrichment, demonstrating greater cutting and toxicity at these off-target sites. Error bars represent range of median results from two replicates. (c) Median and quartile range of truncated 17 and 18 bp guides in three cell lines by number of 1-mismatch off-targets. Guides with any 0-mismatch off-targets were excluded. P values are from a single-tailed Mann–Whitney test compared to guides with 0 off-targets. (d,e) Box plots of enrichment scores for guides targeting hit genes at 10% FDR for (d) growth screens and (e) a ricin screen. Signs have been flipped for ricin resistant genes for comparison. Box is length of quartile, whiskers represent 1.5 × quartile, and dots indicate enrichment of outlier guides. P values calculated using a single-tailed Mann–Whitney test. NS indicates non-significance (P>0.01).

To test the sensitivity of our use of toxicity as a measurement of off-target cutting, we examined the effect of a single mismatch at each nucleotide position. It has been previously reported that the tolerance of a guide to a 1-mismatch off-target depends on where the mismatch lies along the guide, with mismatches closer to the PAM site being less tolerated32,48,49,50. As expected, using the ∼10,000 full-length (19–20 bp) gene-targeting sgRNAs with a single 1-mismatch off-target site elsewhere in the genome, we observe that guides with a mismatch more distal from the PAM are more toxic than sgRNAs with a mismatch closer to the PAM (mismatch position versus average median value of two replicates; Pearson rho>0.7; P value<0.001; Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 9c). Previous results have also found that high GC content sgRNAs suffer greater off-target activity32. Consistent with this, we find that low GC, full-length (19–20 bp) sgRNAs with exactly one 1-mismatch site are significantly less toxic (GC content versus enrichment; Pearson rho<−0.03; P value<0.001) than high GC, full-length sgRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 10). Together, these results demonstrate—using ∼10,000 sgRNAs—that toxicity can be used as a sensitive measure of Cas9 cutting and reproduces previously demonstrated features of sgRNAs that influence off-target activity.

On- and off-target activity of truncated sgRNAs

Since our library contains truncated and full-length sgRNAs, and we can measure off-target cutting using toxicity, we sought to directly compare their relative performance in high-throughput screens. For the ∼10,000 truncated (17–18 bp) guides with a single 1-mismatch off-target site, we observed greatly reduced off-target activity (compare Fig. 2a,c, Supplementary Figs 11a,c,d and 12) and no clear dependence on mismatch position (Supplementary Fig. 11b).

The greater toxicity of full-length guides can still be seen when examining sgRNAs that target essential genes but have no 0- or 1-mismatch off-targets (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Fig. 13a). Notably, when examining genes whose deletion increases the rate of growth, we still observe that full-length guides are more toxic (Supplementary Fig. 13b). This result raises the question of whether truncated sgRNAs may have reduced off-target activity due to reduced overall activity, leading to a trade-off between on- and off-target activities for Cas9 deletion libraries. If truncated guides have major reductions in on-target activity, then truncated sgRNAs targeting ricin regulators would have reduced phenotypes in the screen for ricin regulators in K562. Unlike in growth screens, where cutting at non-genic sites results in measurable toxicity (Supplementary Fig. 5), off-target sites in genes that influence ricin sensitivity should be rare and thus not confound on-target activity (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). We found a minor but not significant (P>0.01) increase in activity with longer guides as indicated by slightly greater depletion for ricin sensitizers or greater enrichment for protective hits (Fig. 2e; Supplementary Fig. 13c). Thus, our data do not necessarily indicate that truncated sgRNAs have equivalent cutting efficiency, only that they appear effective in high-throughput screens. These results support the conclusion that for screening applications, truncated guides provide fewer off-target effects with no major reduction in on-target efficacy.

Discussion

Here we developed a new genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 based library with variable-length sgRNAs and safe-targeting controls and used it to examine how Cas9 toxicity and off-target cutting can affect genome-wide Cas9 deletion screens in three cell lines. Using toxicity as a sensitive measure of Cas9 off-target activity, we were able to measure cutting only at 0-mismatch, 1-mismatch, and 2-mismatch off-target sites. While Cas9 nuclease has been shown to tolerate many more mismatches, these cutting events may occur at too low a frequency to significantly influence high-throughput screens. To correct for the effects of nuclease toxicity we developed safe-targeting sgRNAs—directed towards sites with minimal predicted functional impact—as more appropriate negative controls in CRISPR-Cas9 experiments. Finally, we have demonstrated with thousands of guides the reduced off-target activity of truncated sgRNAs without major loss of on-target efficacy in the context of high-throughput screens.

While the presented library was designed to test hypotheses about sgRNA length, controls, and off-targets, it also represents a robust tool for genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 deletions screens. Existing gold-standard sets for essential genes38 allow the direct measurement of the library's high performance across multiple cell lines (Fig. 1c). While no such gold-standard set exists for ricin regulators, the identification of previous hits and the completeness of known pathways controlling ricin susceptibility provides strong evidence for high performance of this library in selection screens as well (Fig. 1d).

We present a class of safe-targeting guides to control for the DNA damage caused by gene-targeting guides. In theory, these should better recapitulate the non-specific effects of gene-targeting guides, and in fact we demonstrate that they behave significantly differently from non-targeting controls in both growth and non-growth screens (Supplementary Figs 5 and 6a,b). As this has a real effect on the screen results (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Fig. 6c), these safe-targeting guides may provide a more appropriate negative control than widely used non-targeting guides. Note this is similar in principle to the use of sgRNAs targeting gold-standard nonessential genes as negative controls to recapitulate the effects of cutting38,51. Interestingly, safe-targeting guides do not behave identically to sgRNAs targeting gold-standard nonessential genes in growth screens (Supplementary Fig. 5), which may be due to distinct cutting behaviour or the presence of weakly essential genes in the gold-standard nonessential set. While we demonstrate the use of safe-targeting guides in the context of high-throughput growth (Fig. 1e) and non-growth screens (Supplementary Fig. 6c), they likely represent more appropriate controls for low-throughput experiments as well.

Using the measurable growth phenotype caused by Cas9 nuclease activity, we developed a method to profile off-targets in high throughput (Fig. 2a). We recovered known effects of GC content and mismatch position on off-target cutting (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 10) and detect off-targets at sites up to 2-mismatches (Supplementary Fig. 8). These conclusions hold true across multiple cell lines, though the effect is reduced for U937 (Fig. 2a,b,d); indeed, off-target effects may differ depending on Cas9 expression level, genetic background or other differences between cell lines. We note that these results appear to contrast with highly sensitive genome-wide off-target profiling methods such as GUIDE-seq32, Digenome-seq27,28, and BLESS26, which monitor DNA breaks and have observed significant cutting at off-target sites with up to 6 mismatches27,28,32. We are not able to measure growth effects from cutting at such sites, suggesting that the vast majority of these cutting events may occur at too low of a frequency to have a detectable effect on cell fitness in our assay. The key advantage of our use of growth phenotype as a proxy measurement for off-target cutting is that it allows us to assay tens of thousands of guides in a single experiment. Though our assay cannot directly measure cutting efficiencies of sgRNAs or detect individual off-target events, by measuring off-targets across thousands of guides, we can extract generalizable conclusions about off-target sites and evaluate strategies to reduce off-target cutting in high-throughput screens. While we measure the effect of off-targets in growth screens, these conclusions should be relevant to preventing off-target effects in non-growth screens as well.

These results establish a convenient and robust method for detection of on- and off-target efficacy of sgRNAs and Cas9 variants in high-throughput, demonstrate a new strategy to use safe-targeting controls to more accurately perform hit selection in Cas9 screens, and may help define new rules for the design of sensitive and specific Cas9 knockout libraries.

Methods

Gene-targeting guides

Exonic guide sites fitting the pattern G(N16–19)NGG were selected. For cases where multiple lengths are possible, only the longest guide was used. These guide sites were then annotated as targeting Ensembl GRCh37 genes models to generate candidate guides towards each gene. For each candidate guide, the following features were annotated: The coding percentage from the 5′ end, the fraction of transcript models the targeted exon appeared in, and the exon number. For genes with multiple transcript models, the median metric across each model was taken. Additionally, the number of off-target sites in the genome up to 4 mismatches was calculated, considering only G(N16–19)NGG as possible off-targets with a two-basepair seed region.

Candidate guides were removed if they contained restriction enzyme sites necessary for cloning or TTTT homopolymers, which indicate transcription stop from the U6 promoter driving sgRNA expression, as well as those with GGGGG adjacent to the PAM which prevents sequencing on a NextSeq using our sequencing strategy. Guides were then ranked on a weighted scheme for features expected to influence on- and off-target activity. Guides were given 1,000 points for each 0-mismatch off-target, 100 points for each 1-mismatch off-target, 10 points for each 2-mismatch off-target, 500 points times the percentage through the coding region from the translational start, 500 points times the percentage of coding models the targeting site was not included in and 1,000 points if the GC content of the guide was <20% or >80%. To ensure the library would be equally split between full-length (19–20 bp) and truncated (17–18 bp) sgRNAs, full-length guides were given an extra 100 points. Guides were than ranked from lowest to highest number of points. For example, if a guide had no 0-mismatch off-targets, two 1-mismatch off-targets and 10 2-mismatch off-targets, then it would receive 0 × 1,000+2 × 100+10 × 10=300 points. If the guide was located in an exon present in four fifths of transcript models, then it would receive 500(1−4/5)=100 points. If the targeting site was 20% through the coding region from the translational start, it would receive 500 × 0.2=100 points. If the guide had normal GC content and was truncated, it would receive no additional points for a total of 300+100+100=500 points. It would then be ranked against all other guides targeting that gene, from lowest to highest points.

After this initial ranking, additional penalties were used to select more variable guides: If a guide overlapped a higher ranking guide, 500 points was given. If a guide targeted the same exon as five higher ranking guides, 500 points was given. These additional penalties were given based only on the original ranking. The top 10 guides towards each gene, those with the lowest score, were then selected (Supplementary Data 1 and 2). Note that for genes with few candidate guides, this results in the inclusion of poor quality guides. Relative penalties were selected based on the observed distribution of guide qualities.

Non-targeting guides

To design non-targeting negative control guides with similar properties to the targeting guides, the selected gene-targeting guides were scrambled and tested for intended properties. Each targeting guide was used to generate a candidate non-targeting guide sequence by retaining the nucleotide composition and length of the guide and permuting the sequence. Candidate non-targeting guides were not considered if they contained 5′-GGGGG-3′ or 5′-TTTT-3′ homopolymers or restriction sites. To ensure that non-targeting guides had no targets in the genome, the 17 PAM-proximal nucleotides were mapped to the genome with BWA52 using both the NAG and NGG PAMs, and sequences which mapped with zero or one mismatch was permuted and tested again. Guides were repeatedly tested in this manner until a guide towards at least 95% of targeted genes had an acceptable permuted version. Of these, 10,000 guides were selected randomly to form the complete set of non-targeting guides, and 5,644 of these were chosen randomly to be included in the library (Supplementary Data 5).

Safe-targeting guides

We defined safe regions as genomic regions without detectable signals across a range of biochemical assays and sequence-based analyses. We performed this analysis on the human hg19 assembly. We first identified the regions classified in inactive chromatin states (Quies, ReprPC. ReprPCWk or Het) across all available cell types in the Roadmap Epigenomics project53. The intersection of these gives the genomic regions that are inactive in every one of these cell types. From these, we filtered out the following: conserved elements, as defined from GERP34, phastCons32PlacentalMammals, phastCons46Vertebrates, phastCons9Primates, SiPhy29Mammals, DNase peaks from the ENCODE project54, repeats downloaded from IGV browser tracks (SINE, LINE, LTR, DNA, Simple_repeat, Low_complexity, Satellite, RC, RNA, Other Unknown), transcription factor binding motifs defined in the ENCODE project across the hg19 genome to find significant motif matches55, transcription factor binding sites as defined by ChIP-seq experiments from the ENCODE projects using the irreproducible discovery rate (IDR) pipeline56, sites on the genome blacklist54, unmappable regions, gene exons and UTRs from GENCODE v19 (ref. 57), and transcription start sites from combined analysis of Gencode annotations and CAGE-seq data from the Fantom5 consortium. Given that some of the criteria are not available on chrX, there is an enrichment of safe regions for that chromosome. Thus, we selected 10,000 safe-targeting controls evenly distributed across chromosomes and included 6,750 of these based on off-targets and GC content (Supplementary Data 5).

Cell culture

Cell culture performed as previously described35. Briefly, K562 (ATCC) and Ramos (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) media and supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone), penicillin (10,000 I.U ml−1), and L-glutamine (2 mM). U937 (ATCC) were cultured RPMI 1640 (Gibco) media and supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Hyclone) and penicillin (10,000 I.U ml−1). Cells were grown in log phase during all biological assays by returning the population to 500,000 cells per ml each day. K562, Ramos, and U937 cells were maintained in a controlled humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Screening

Pooled, genome-wide CRISPR deletion screens were performed in three cell lines: K562 stably expressing SFFV-Cas9-BFP, Ramos cells lentivirally infected with SFFV-Cas9-BFP, and U937 cells lentivirally infected with EF1a-Cas9-Blast34. The library was synthesized, cloned and lentivirally infected into cells as previously described20. Briefly, the parent vector for the libraries was derived from a pSico lentiviral vector which expresses GFP and a puromycin-resistance cassette separated by a T2A sequence45,58; we replaced GFP with mCherry to make the final parent vector, pMCB320. Sublibraries were PCR-amplified from pooled-oligo chips (CustomArray, Agilent), digested with BstXI and BlpI restriction enzymes, and ligated into BstXI/BlpI-cut pMCB320 using T4 ligase. Libraries and vectors will be made available via Addgene. Three days after infection, cells were placed under puromycin selection (0.7 μg ml−1, Sigma) for an additional 3 days after infection, then split at time 0. Throughout the screen, the pooled libraries were maintained at 1,000 cells per guide or a total of ∼250 million cells in large spinner flasks. K562 and U937 were grown for ∼2 weeks, and Ramos cells were growth for ∼3 weeks due to their slower division time. Genomic DNA was extracted following Qiagen's Blood Maxi Kit, and the guide composition was sequenced and compared to the plasmid library using casTLE20 version 1.0 available at https://bitbucket.org/dmorgens/castle. Briefly, casTLE compares each set of gene-targeting guides to the negative controls, selecting the most likely maximum effect size which explains the distribution of targeting guides. It then determines the significance of this maximum effect by permuting the results20. Both safe-targeting and non-targeting controls were used for this analysis. For the ricin sensitivity screen, cells were treated with ricin toxin (Vector Labs) at 0.25 ng ml−1 for 24 h, ricin was removed and then cells were allowed to recover to normal doubling rate. This treatment occurred four times over 2 weeks.

Off-target analysis

Genome-wide off-target sites with up to 2 single-nucleotide mismatches were found via the BWA alignment software52 with no seed region (Supplementary Data 7). Enrichment values for each guide in each screen were calculated as a log ratio of counts, normalized for sequencing depth and the median enrichment of both non-targeting and safe-targeting negative controls as previously described20.

Data availability

All sequencing data used for the screens is available from the authors. Count files containing element-wise summaries of the sequencing data are available as Supplementary Data 3. Full gene-wise summaries of screens are also available as Supplementary Data 4. Off-target data used for all figures is available as Supplementary Data 7.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Morgens, D. W. et al. Genome-scale measurement of off-target activity using Cas9 toxicity in high-throughput screens. Nat. Commun. 8, 15178 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15178 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Human CRISPR-Cas9 library. Guide sequences and sublibrary breakdown for the 10-guide human library.

Mouse CRISPR-Cas9 library. Guide sequences and sublibrary breakdown for the 10-guide mouse library.

Count files for all screens. Files containing counts for each guide sequence in each condition.

Screen results. Full casTLE results for each screen.

Human and mouse controls. Lists of all non-targeting guides. Lists of all designed safe-targeting guides, including those not used in screens. Lists of safe regions used to select guides.

Non-targeting vs safe-targeting. Lists of genes that are differentially identified when using either non-targeting or safe-targeting controls.

Summary of off-target information. Number of predicted off-targets for each guide in each screen.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Dubreuil, R.M. Deans, C.H. Lee, J.D. Smith, J.M. Geisinger, B.X.H. Fu, members of the Bassik lab, Doug Vollrath, Max Horlbeck, Luke Gilbert, Martin Kampmann and Jonathan Weissman for technical expertise and helpful discussions. We thank Laurakay Bruhn, Steven Altschuler, Marc Valer, Ben Borgo, Peter Sheffield and Carsten Carstens of Agilent Inc. for oligonucleotide synthesis and helpful discussions. This work was funded by the NIH Director's New Innovator Award Program (project no 1DP2HD084069-01) NIH/NHGRI (training grant T32 HG000044 to D.W.M. and G.T.H.), and seed grants from Stanford ChEM-H and Stanford Neuroscience Institute. This material is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship (grant DGE-114747 to D.W.M.) and by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Postgraduate Scholarship-Doctoral (grant PGSD3-476082-2015 to M.W.). Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF or NSERC.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions D.W.M. and M.C.B. conceived and designed the study. D.W.M., E.A.B., O.U., C.L.A., G.T.H., K.H., A.K. and M.C.B. designed the library. C.L.A. generated sgRNAs sequences and performed off-target detection. O.U. identified safe regions. E.A.B. annotated guide sites. D.W.M. selected guides. K.H., E.E.J. and A.L. cloned libraries. A.L., C.K.T., M.S.H. and G.T.H. performed screens. M.W. and D.W.M. performed analyses. M.P.S., W.J.G., A.K. and M.C.B. supervised the study. D.W.M., M.W. and M.C.B. wrote manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

References

- Shalem O., Sanjana N. E. & Zhang F. High-throughput functional genomics using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 299–311 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Wei J. J., Sabatini D. M. & Lander E. S. Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science 343, 80–84 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalem O. et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science 343, 84–87 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike-Yusa H., Li Y., Tan E.-P., Velasco-Herrera M. D. C. & Yusa K. Genome-wide recessive genetic screening in mammalian cells with a lentiviral CRISPR-guide RNA library. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 267–273 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. et al. High-throughput screening of a CRISPR/Cas9 library for functional genomics in human cells. Nature 509, 487–491 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbie D. A. et al. Systematic RNA interference reveals that oncogenic KRAS-driven cancers require TBK1. Nature 462, 108–112 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampmann M., Bassik M. C. & Weissman J. S. Integrated platform for genome-wide screening and construction of high-density genetic interaction maps in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E2317–E2326 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J. M. et al. Profiling essential genes in human mammary cells by multiplex RNAi screening. Science 319, 617–620 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Alvear D. et al. Paradoxical resistance of multiple myeloma to proteasome inhibitors by decreased levels of 19S proteasomal subunits. Elife 4, e08153 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R. et al. Advances in CRISPR-Cas9 genome engineering: lessons learned from RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 3407–3419 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham A. et al. 3′ UTR seed matches, but not overall identity, are associated with RNAi off-targets. Nat. Methods 3, 199–204 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D. et al. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature 441, 537–541 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. L. et al. Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 635–637 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. L. & Linsley P. S. Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off-target effects for target identification and therapeutic application. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 57–67 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin W. G. Use and abuse of RNAi to study mammalian gene function. Science 337, 421–422 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampmann M. et al. Next-generation libraries for robust RNA interference-based genome-wide screens. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E3384–E3391 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S., Kweon J., Kim H. S. & Kim J.-S. Microhomology-based choice of Cas9 nuclease target sites. Nat. Methods 11, 705–706 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnas O. et al. A genome-wide CRISPR screen in primary immune cells to dissect regulatory networks. Cell 162, 675–686 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J. et al. Discovery of cancer drug targets by CRISPR-Cas9 screening of protein domains. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 661–667 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgens D. W., Deans R. M., Li A. & Bassik M. C. Systematic comparison of CRISPR/Cas9 and RNAi screens for essential genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 634–636 1–4 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett-Miller S. M., Reading D. W., Porter S. N. & Porteus M. H. Attenuation of zinc finger nuclease toxicity by small-molecule regulation of protein levels. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000376 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre A. J. et al. Genomic copy number dictates a gene-independent cell response to CRISPR-Cas9 targeting. Cancer Discov. 6, 914–929 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz D. M. et al. CRISPR screens provide a comprehensive assessment of cancer vulnerabilities but generate false-positive hits for highly amplified genomic regions. Cancer Discov. 6, 900–913 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. M. et al. Systematic analysis of CRISPR-Cas9 mismatch tolerance reveals low levels of off-target activity. J. Biotechnol. 211, 56–65 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cradick T. J., Fine E. J., Antico C. J. & Bao G. CRISPR/Cas9 systems targeting β-globin and CCR5 genes have substantial off-target activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 9584–9592 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosetto N. et al. Nucleotide-resolution DNA double-strand break mapping by next-generation sequencing. Nat. Methods 10, 361–365 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. et al. Digenome-seq: genome-wide profiling of CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects in human cells. Nat. Methods 12, 237–243 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Kim S., Kim S., Park J. & Kim J.-S. Genome-wide target specificities of CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases revealed by multiplex Digenome-seq. Genome Res. 26, 406–415 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 systems have off-target activity with insertions or deletions between target DNA and guide RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 7473–7485 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Geen H., Henry I. M., Bhakta M. S., Meckler J. F. & Segal D. J. A genome-wide analysis of Cas9 binding specificity using ChIP-seq and targeted sequence capture. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 3389–3404 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S. Q. & Joung J. K. Defining and improving the genome-wide specificities of CRISPR–Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 300–312 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S. Q. et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 187–197 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassik M. C. et al. A systematic mammalian genetic interaction map reveals pathways underlying ricin susceptibility. Cell 152, 909–922 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjana N. E., Shalem O. & Zhang F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat. Methods 11, 783–784 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans R. M. et al. Parallel shRNA and CRISPR-Cas9 screens enable antiviral drug target identification. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 361–366 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T. et al. Identification and characterization of essential genes in the human genome. Science 350, 1096–1101 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. et al. Genome-wide binding of the CRISPR endonuclease Cas9 in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 670–676 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart T., Brown K. R., Sircoulomb F., Rottapel R. & Moffat J. Measuring error rates in genomic perturbation screens: gold standards for human functional genomics. Mol. Syst. Biol. 10, 733 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S. W. et al. Analysis of off-target effects of CRISPR/Cas-derived RNA-guided endonucleases and nickases. Genome Res. 24, 132–141 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Sander J. D., Reyon D., Cascio V. M. & Joung J. K. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 279–284 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S. Q. et al. Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided FokI nucleases for highly specific genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 569–576 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaymaker I. M. et al. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science 351, 84–88 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstiver B. P. et al. High-fidelity CRISPR–Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature 529, 490–495 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu B. X., Onge R. P., Fire A. Z. & Smith J. D. Distinct patterns of Cas9 mismatch tolerance in vitro and in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 5365–5377 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L. A. et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-mediated control of gene repression and activation. Cell 159, 647–661 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispin M. et al. A human embryonic kidney 293T cell line mutated at the Golgi alpha-mannosidase II locus. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21684–21695 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings R. D. & Etzler M. E. R-type Lectins. Essentials of Glycobiology Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenova E. et al. Interference by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) RNA is governed by a seed sequence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 10098–10103 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M. et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg S. H., Redding S., Jinek M., Greene E. C. & Doudna J. A. DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature 507, 62–67 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart T. et al. High-resolution CRISPR screens reveal fitness genes and genotype-specific cancer liabilities. Cell 163, 1515–1526 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. & Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roadmap Epigenome Consortium. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature 518, 317–330 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein B. E. et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489, 57–74 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheradpour P. & Kellis M. Systematic discovery and characterization of regulatory motifs in ENCODE TF binding experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 2976–2987 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Brown J. B., Huang H. & Bickel P. J. Measuring reproducibility of high-throughput experiments. Ann. Appl. Stat. 5, 1752–1779 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Harrow J. et al. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome Res. 22, 1760–1774 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. et al. Dynamic Imaging of Genomic Loci in Living Human Cells by an Optimized CRISPR/Cas System. Cell 155, 1479–1491 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.

Human CRISPR-Cas9 library. Guide sequences and sublibrary breakdown for the 10-guide human library.

Mouse CRISPR-Cas9 library. Guide sequences and sublibrary breakdown for the 10-guide mouse library.

Count files for all screens. Files containing counts for each guide sequence in each condition.

Screen results. Full casTLE results for each screen.

Human and mouse controls. Lists of all non-targeting guides. Lists of all designed safe-targeting guides, including those not used in screens. Lists of safe regions used to select guides.

Non-targeting vs safe-targeting. Lists of genes that are differentially identified when using either non-targeting or safe-targeting controls.

Summary of off-target information. Number of predicted off-targets for each guide in each screen.

Data Availability Statement

All sequencing data used for the screens is available from the authors. Count files containing element-wise summaries of the sequencing data are available as Supplementary Data 3. Full gene-wise summaries of screens are also available as Supplementary Data 4. Off-target data used for all figures is available as Supplementary Data 7.