Abstract

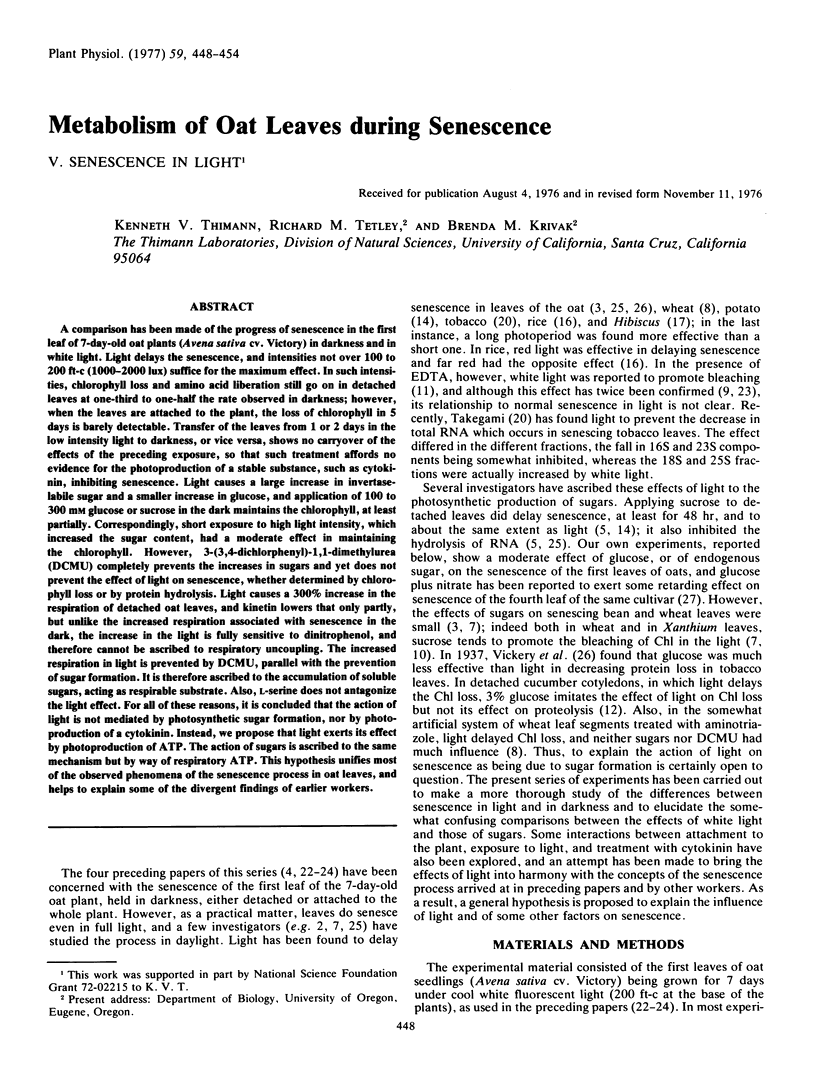

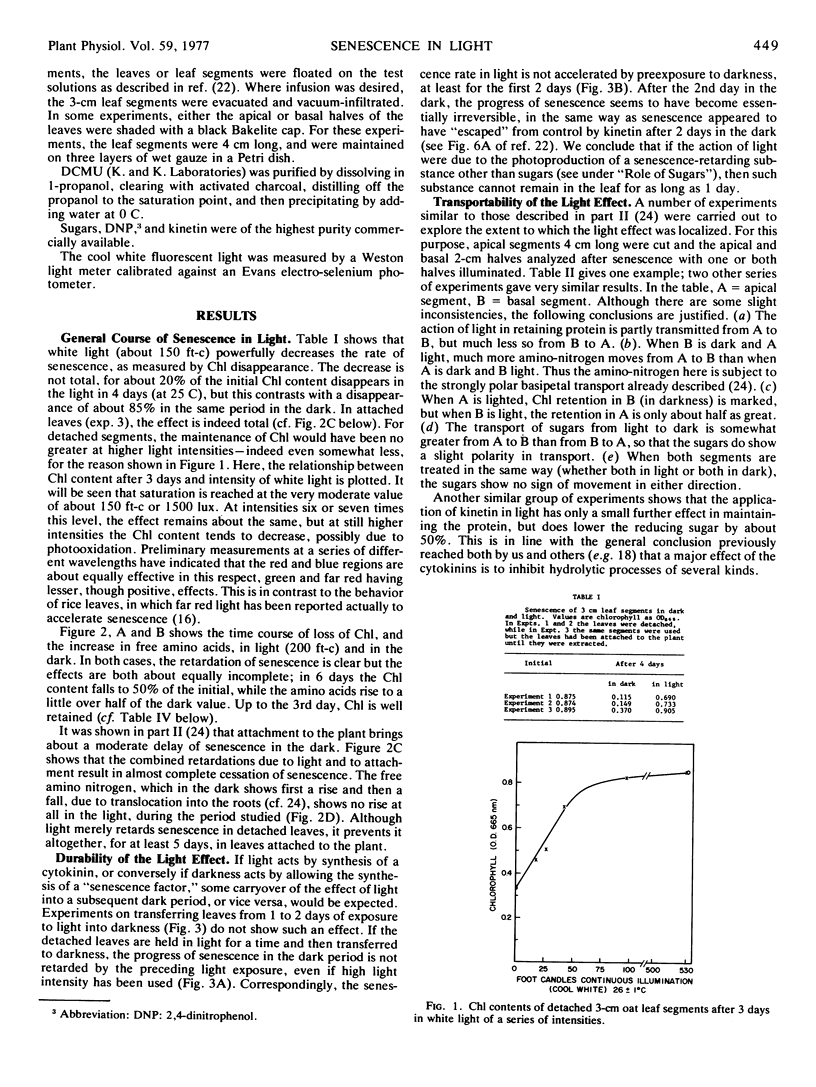

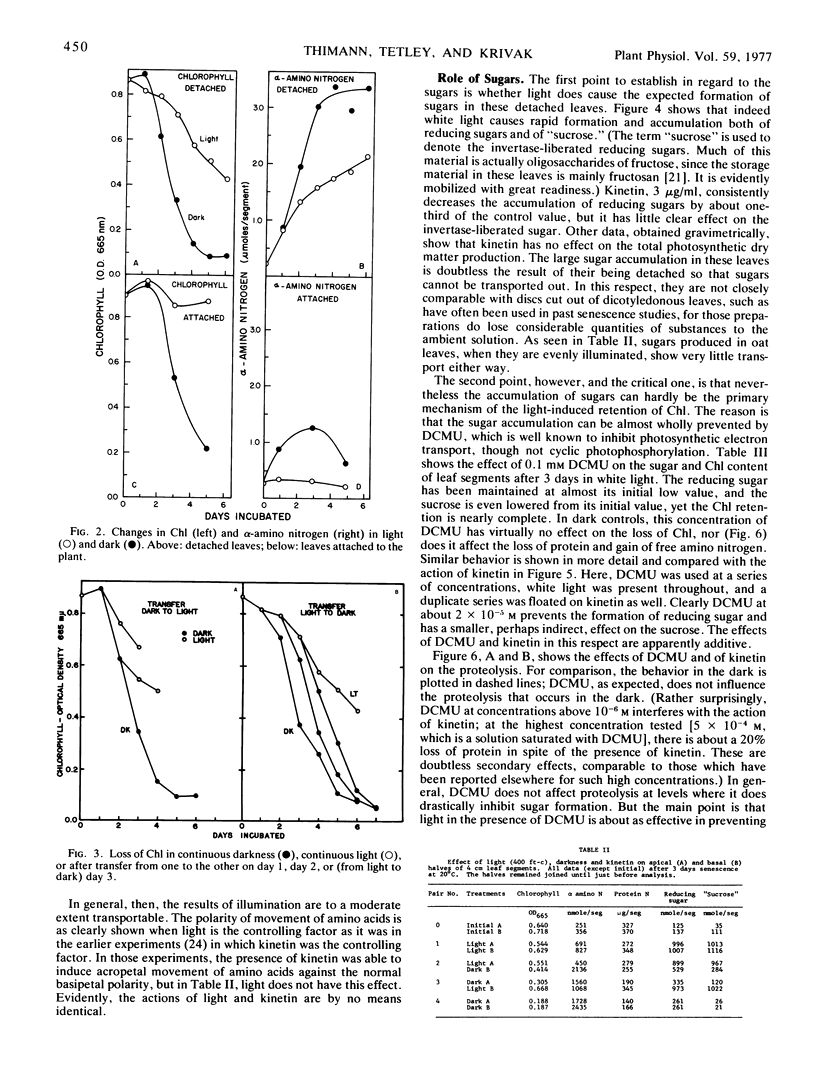

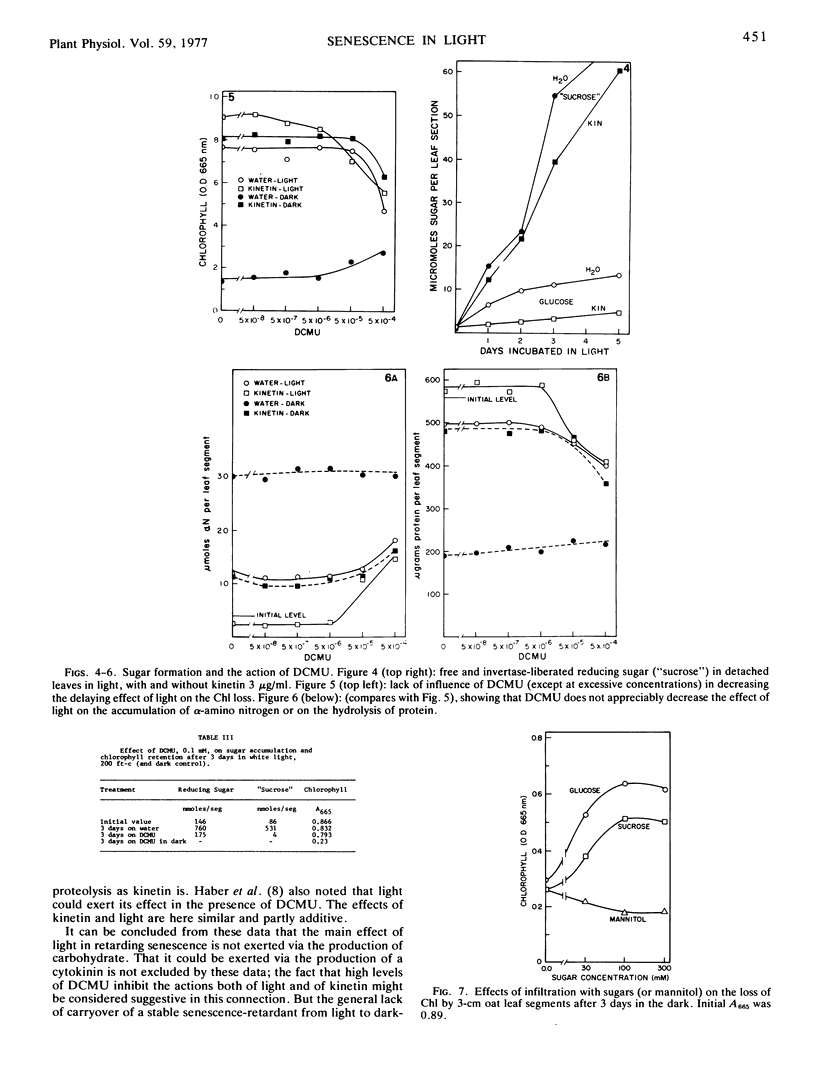

A comparison has been made of the progress of senescence in the first leaf of 7-day-old oat plants (Avena sativa cv. Victory) in darkness and in white light. Light delays the senescence, and intensities not over 100 to 200 ft-c (1000-2000 lux) suffice for the maximum effect. In such intensities, chlorophyll loss and amino acid liberation still go on in detached leaves at one-third to one-half the rate observed in darkness; however, when the leaves are attached to the plant, the loss of chlorophyll in 5 days is barely detectable. Transfer of the leaves from 1 or 2 days in the low intensity light to darkness, or vice versa, shows no carryover of the effects of the preceding exposure, so that such treatment affords no evidence for the photoproduction of a stable substance, such as cytokinin, inhibiting senescence. Light causes a large increase in invertaselabile sugar and a smaller increase in glucose, and application of 100 to 300 mm glucose or sucrose in the dark maintains the chlorophyll, at least partially. Correspondingly, short exposure to high light intensity, which increased the sugar content, had a moderate effect in maintaining the chlorophyll. However, 3-(3,4-dichlorphenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) completely prevents the increases in sugars and yet does not prevent the effect of light on senescence, whether determined by chlorophyll loss or by protein hydrolysis. Light causes a 300% increase in the respiration of detached oat leaves, and kinetin lowers that only partly, but unlike the increased respiration associated with senescence in the dark, the increase in the light is fully sensitive to dinitrophenol, and therefore cannot be ascribed to respiratory uncoupling. The increased respiration in light is prevented by DCMU, parallel with the prevention of sugar formation. It is therefore ascribed to the accumulation of soluble sugars, acting as respirable substrate. Also, l-serine does not antagonize the light effect. For all of these reasons, it is concluded that the action of light is not mediated by photosynthetic sugar formation, nor by photoproduction of a cytokinin. Instead, we propose that light exerts its effect by photoproduction of ATP. The action of sugars is ascribed to the same mechanism but by way of respiratory ATP. This hypothesis unifies most of the observed phenomena of the senescence process in oat leaves, and helps to explain some of the divergent findings of earlier workers.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aggarwal B. B., Avi-Dor Y., Tinberg H. M., Packer L. Effect of visible light on the mitochondrial inner membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976 Mar 22;69(2):362–368. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. W., Rowan K. S. The effect of 6-furfurylaminopurine on senescence in tobacco-leaf tissue after harvest. Biochem J. 1966 Feb;98(2):401–404. doi: 10.1042/bj0980401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe H. T., Thimann K. V. The Metabolism of Oat Leaves during Senescence: III. The Senescence of Isolated Chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 1975 May;55(5):828–834. doi: 10.1104/pp.55.5.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldthwaite J. J., Laetsch W. M. Regulation of senescence in bean leaf discs by light and chemical growth regulators. Plant Physiol. 1967 Dec;42(12):1757–1762. doi: 10.1104/pp.42.12.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber A. H., Thompson P. J., Walne P. L., Triplett L. L. Nonphotosynthetic retardation of chloroplast senescence by light. Plant Physiol. 1969 Nov;44(11):1619–1628. doi: 10.1104/pp.44.11.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. O., Larkins B. A. Influence of Ionic Strength, pH, and Chelation of Divalent Metals on Isolation of Polyribosomes from Tobacco Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1976 Jan;57(1):5–10. doi: 10.1104/pp.57.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotaka S., Krueger A. P. Some observations on the bleaching of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid on green barley leaves. Plant Physiol. 1969 Jun;44(6):809–815. doi: 10.1104/pp.44.6.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACLACHLAN G. A., PORTER H. K. Replacement of oxidation by light as the energy source for glucose metabolism in tobacco leaf. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1959 Sep 1;150:460–473. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1959.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C., Thimann K. V. Role of Protein Synthesis in the Senescence of Leaves: II. The Influence of Amino Acids on Senescence. Plant Physiol. 1972 Oct;50(4):432–437. doi: 10.1104/pp.50.4.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra D., Pradhan P. Regulation of senescence in detached rice leaves by light, benzimidazole and kinetin. Exp Gerontol. 1973 Jun;8(3):153–155. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(73)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetley R. M., Thimann K. V. The Metabolism of Oat Leaves during Senescence: I. Respiration, Carbohydrate Metabolism, and the Action of Cytokinins. Plant Physiol. 1974 Sep;54(3):294–303. doi: 10.1104/pp.54.3.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetley R. M., Thimann K. V. The Metabolism of Oat Leaves during Senescence: IV. The Effects of alphaalpha'-Dipyridyl and other Metal Chelators on Senescence. Plant Physiol. 1975 Jul;56(1):140–142. doi: 10.1104/pp.56.1.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimann K. V., Tetley R. R., Van Thanh T. The Metabolism of Oat Leaves during Senescence: II. Senescence in Leaves Attached to the Plant. Plant Physiol. 1974 Dec;54(6):859–862. doi: 10.1104/pp.54.6.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]