Abstract

Background

Up-regulation of interleukin 17 (IL-17) family cytokines and acute phase response have been observed in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). It has been demonstrated that IL-17 stimulates C-reactive protein (CRP) expression.

Aim

To determine relationship between circulating concentrations of IL-17 and CRP in CSU.

Methods

Concentrations of IL-17 in plasma and CRP in serum were measured in patients with CSU of varying severity and in the healthy subjects.

Results

IL-17 and CRP concentrations were significantly higher in CSU patients as compared to the healthy subjects. In addition, there were significant differences in IL-17 and CRP concentrations between CSU patients with mild, moderate-severe symptoms and the healthy subjects. CRP did not correlate significantly with IL-17.

Conclusions

Increased circulating IL-17 concentration may represent an independent index of systemic inflammatory response in CSU, which is not related to increased CRP concentration.

Keywords: Chronic spontaneous urticaria, C-reactive protein, IL-17 interleukin

Background

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a complex, systemic disease with a multifactorial etiopathogenesis associated with autoimmune and inflammatory phenomena [1–3].

It has been hypothesized that CSU is associated with a T helper cell 17 (Th17)—mediated immune response [4, 5], which is characterized by production of interleukin 17 (IL-17). IL-17 is linked to pathogenesis of inflammatory/autoimmune diseases [6, 7].

The pro-inflammatory cytokine plays an important role in synthesis of many mediators, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β and TNF-α [6, 8], which may reflect the inflammatory state in CSU [2, 4, 5].

Serum C reactive protein (CRP)—the best marker of acute phase response and IL-17 concentrations, may be associated with CSU activity [2, 5]. It has been suggested that IL-17-CRP signaling may play a role in chronic inflammatory conditions [9], although, its regulation and function in CSU have remained unclear. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the relationship between circulating concentrations of IL-17 and CRP in CSU patients.

Methods

52 CSU patients (14 men and 38 women; median age: 38 years, range: 24–50) with a median disease duration of 2.5 years were enrolled in the study.

The patients underwent the following tests and procedures: routine laboratory tests, stool (for parasites and H. pylori), antinuclear and antithyroid microsomal antibodies, thyroid function, chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasonography, hepatitis serology, autologous serum skin test (ASST) [10]. Additionally, dental, gynecological and ENT consultations were performed.

Urticaria activity score according to EAACI/GALEN/EDF guidelines was estimated during four days and on the blood sampling day and graded as follows: mild (0–8), moderate (9–16) and severe (17–24). The study comprised 28 patients with mild CSU and 24 patients with moderate-severe symptoms.

H1-antihistamine drugs were withdrawn at least 4 days before blood sampling. None of the patients had been taking immunosuppressants or any other drugs, for at least 8 weeks before the study.

The control group comprised 21 sex-, age- and BMI (<30) matched the healthy subjects.

The Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Silesia approved of the study and written, informed consent was obtained from all the subjects participating.

Blood collection

Blood samples were taken on fasting, from elbow veins using tubes with anticoagulant. Plasma obtained by centrifugation were stored at −85 °C until the tests were performed.

Assay of interleukin-17 (IL-17)

Concentrations of IL-17 in plasma samples were measured by ELISA method using commercially available kits (Quantikine Human CXCL8/IL-8 ELISA kit from R&D Systems, MN, USA) according to manufacturers’ detailed instructions. The variance coefficients for intra-assay and inter-assay were below 8 and 10% respectively. Sensitivity of the kit is 15 pg/ml.

CRP assay

Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations were measured using Roche/Hitachi cobas c system. Normal lab ranges: lower than 5.0 mg/l.

Statistical analysis

The obtained results were presented with the use of basic parameters of descriptive statistics. Normal distribution of data was measured using Shapiro–Wilk’s test. Independent data between two groups of patients with CSU and the controls were compared using non-parametric U Mann–Whitney test. Independent data between three groups of patients with mildCSU, moderate-severe CSU and the controls were compared using non-parametric ANOVA rang Kruskal–Wallis’s test. The Spearman’s rank test was used for correlations. The p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Calculations were performed with STATISTICA for Windows 10.0 software (StatSoft, Cracow, Poland).

Results

Plasma IL-17 concentration

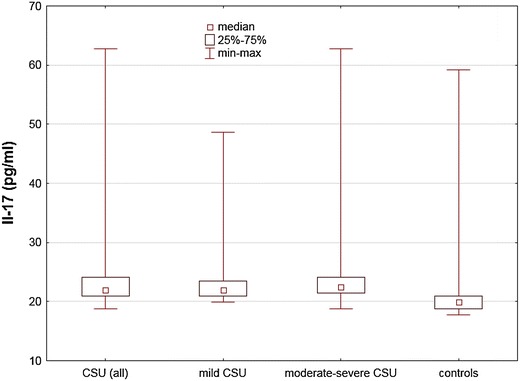

Plasma concentrations of IL-17 were significantly higher in CSU patients as compared with the healthy subjects [median and quartile range/min–max: 21.97 (20.92–24.98/18.85–62.73) vs. 19.88 (18.85–20.92/17.82–59.16) pg/ml, p < 0.001; Fig. 1].

Fig. 1.

Plasma IL-17 concentration in chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) patients with different disease activity and in the healthy subjects. CSU vs. controls, p < 0.001; moderate-severe CSU patients and mild CSU vs. controls, p < 0.005; mild CSU vs. moderate-severe CSU, p > 0.05

IL-17 plasma concentrations were significantly higher in moderate-severe and mild CSU patients as compared with the healthy subjects [median and quartile range/min–max: 22.49 (20.92–24.08/18.85–62.73) and 21.97 (20.92–23.55/19.28–48.60) vs. 19.88 (18.85–20.92/17.82–59.16) pg/ml, p < 0.005]. Concentrations of IL-17 in mild CSU patients did not differ significantly versus moderate-severe CSU patients [median and quartile range/min–max: 21.97 (20.92–23.55/19.28–48.60) vs. 22.49 (20.92–24.08/18.85–62.73) pg/ml, p > 0.05; Fig. 1].

No significant differences in IL-17 concentrations between ASST(+) and ASST(−) CSU patients (selected according to the similar UAS) were observed.

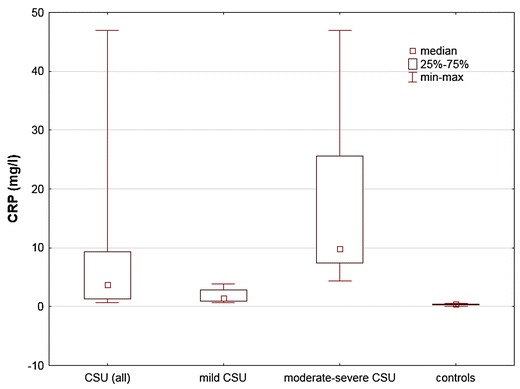

Serum CRP concentration

Serum CRP concentrations were significantly higher in CSU patients as compared with the healthy subjects [median and quartile range/min–max: 3.8 (1.30–9.20/0.70–46.90) vs. 0.4 (0.20–0.40/0.10–0.60) mg/l, p < 0.001]. In addition, there were significant differences in serum CRP concentration between CSU patients with mild, moderate-severe symptoms and the healthy subjects [median and quartile range/min–max: 1.4 (20.92–23.55/19.28–48.60) vs. 9.8 (20.92–24.08/18.85–62.73) vs. 0.4 (0.20–0.40/0.10–0.60) mg/l, respectively; p < 0.001; Fig. 2].

Fig. 2.

CRP concentration in serum of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) patients and in the healthy subjects. CSU vs. controls, p < 0.001; mild CSU vs. moderate-severe CSU vs. controls, p < 0.001

Correlation between values of CRP and IL-17 in patients with CSU

CRP did not correlate significantly with IL-17 (r = 0.12, p = 0.41).

Discussion

In our study, plasma IL-17 concentrations were significantly higher in CSU patients as compared with the healthy subjects. In addition, there were significant differences in IL-17 concentrations between CSU patients with mild, moderate-severe symptoms and the healthy subjects. However, IL-17 values did not show significant differences between the groups of mild and moderate-severe disease. Atwa et al. reported increased IL-17 serum concentrations in CSU patients that paralleled disease severity and ASST response [5]. In addition, there is some convincing evidence to prove that acute phase activation is associated with CSU activity/severity and may be involved in pathogenesis of the disease [2]. Based on association between acute phase response and IL-17, we addressed the question whether increased IL-17 and CRP are related to each other.

It has been demonstrated that IL-17 can stimulate CRP and IL-6 expression, suggesting that the cross-talk between IL-17 and CRP/IL-6 may further amplify an inflammatory cascade [9, 11].

It is known that IL-6-CRP signaling plays an important role in CSU. Interestingly, it has been suggested that IL-17 stimulates CRP expression independently of IL-1 and IL-6. However, IL-17 may act in synergy with IL-6, which potentiates IL-17-mediated CRP expression. [9].

The link between IL-6 and CRP has been confirmed in CSU [2]. In the present study, we did not observe any association between CRP and IL-17 concentrations in CSU patients, contrary to the expectations.

The lack of correlation between IL-17 and CRP suggests, that increased IL-17 concentration cannot be regarded as a simple reflection of acute phase activation. IL-17 seems to be related to a wider spectrum of immune/inflammatory responses and provides independent information from the acute phase response in CSU. CRP concentration is increased in CSU patients and it may reflect the disease activity/severity. However, mild urticarial processes can result in only slight elevation (within normal range) of the acute phase response marker.

Th17 cells and their signature cytokine—IL-17 play a key role in initiation and maintenance of autoimmune and inflammatory processes in different diseases, leading to secretion of several inflammatory factors and autoantibody production [7, 12].

The source of IL-17 in CSU is unclear. Elevated IL-17 is likely to result from activation of different cells involved in urticarial processes, especially mast cells [13]. It has been demonstrated that mast cells primarily MCTC cells, are the most numerous cells containing IL-17 in human skin [13]. These cells are able to produce IL-17 upon stimulation with various stimuli, including TNF-alpha and C5a [13]. IL-17 is produced by many other cell types including lymphocytes, neutrophils [14, 15].

All of these factors are upregulated and may play role in pathogenesis of immune-inflammatory response in CSU [1, 16].

The current study confirms that circulating IL-17 concentrations are increased in CSU patients [4, 5]. Similar observations have been made in various inflammatory and autoimmune diseases providing the rationale for development of the anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody [6, 14]. Therefore, it seems that biological agents targeting IL-17A signalling pathways may represent a potential approach for treating CSU.

Conclusions

The current finding confirms that circulating IL-17 concentration is increased in CSU patients and may represent an independent index of systemic inflammatory response, which is not related to increased CRP concentration.

Authors’ contributions

AG designed the study, provided clinical data, contributed to data analysis and interpretation and wrote the manuscript. ADB performed the lab and statistical data analysis. AKZ conceived the study and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Silesia approved of the study and written, informed consent was obtained from all the subjects participating (KNW-640-2-1-004/15).

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from the Committee for Scientific Research.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- CSU

chronic spontaneous urticaria

- CRP

C reactive protein

- IL-17

interleukin 17

- UAS

urticaria activity score

- ASST

autologous serum skin test

Contributor Information

A. Grzanka, Email: alicjag@mp.pl

A. Damasiewicz-Bodzek, Email: olabodzek@interia.pl

A. Kasperska-Zajac, Email: alakasperska@gmail.com

References

- 1.Asero R, Tedeschi A, Marzano AV, Cugno M. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: immune system, blood coagulation, and more. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12:229–231. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2016.1127160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasperska-Zajac A, Grzanka A, Damasiewicz-Bodzek A. IL-6 signaling in chronic spontaneous urticaria. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0145751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasperska-Zajac A, Grzanka A, Kowalczyk J, Wyszyńska-Chłap M, Lisowska G, Kasperski J, Jarząb J, Misiołek M, Kalarus Z. Refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria and permanent atrial fibrillation associated with dental infection: mere coincidence or something more to it? Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29:112–120. doi: 10.1177/0394632015617770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dos Santos JC, Azor MH, Nojima VY, Lourenço FD, Prearo E, Maruta CW, Rivitti EA, da Silva Duarte AJ, Sato MN. Increased circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and imbalanced regulatory T-cell cytokines production in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:1433–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atwa MA, Emara AS, Youssef N, Bayoumy NM. Serum concentration of IL-17, IL-23 and TNF-α among patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: association with disease activity and autologous serum skin test. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:469–474. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu S, Qian Y. IL-17/IL-17 receptor system in autoimmune disease: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122:487–511. doi: 10.1042/CS20110496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim BS, Park YJ, Chung Y. Targeting IL-17 in autoimmunity and inflammation. Arch Pharm Res. 2016;39:1537–1547. doi: 10.1007/s12272-016-0823-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fossiez F, Djossou O, Chomarat P, Flores-Romo L, Ait-Yahia S, Maat C, Pin JJ, Garrone P, Garcia E, Saeland S, Blanchard D, Gaillard C, Das Mahapatra B, Rouvier E, Golstein P, Banchereau J, Lebecque S. T cell interleukin-17 induces stromal cells to produce proinflammatory and hematopoietic cytokines. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2593–2603. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel DN, King CA, Bailey SR, Holt JW, Venkatachalam K, Agrawal A, Valente AJ, Chandrasekar B. Interleukin-17 stimulates C-reactive protein expression in hepatocytes and smooth muscle cells via p38 MAPK and ERK1/2-dependent NF-kappaB and C/EBPbeta activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27229–27238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703250200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabroe RA, Grattan CEH, Francis DM, Barr RM, Kobza Black A, Greaves MW. The autologous serum skin test: a screening test for autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticatia. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:446–453. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eklund CM. Proinflammatory cytokines in CRP baseline regulation. Adv Clin Chem. 2009;48:111–136. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2423(09)48005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beringer A, Noack M, Miossec P. IL-17 in chronic inflammation: from discovery to targeting. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:230–241. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hueber AJ, Asquith DL, Miller AM, Reilly J, Kerr S, Leipe J, Melendez AJ, McInnes IB. Mast cells express IL-17A in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. J Immunol. 2010;184:3336–3340. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkham BW, Kavanaugh A, Reich K. Interleukin-17A: a unique pathway in immune-mediated diseases: psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Immunology. 2014;141:133–142. doi: 10.1111/imm.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin HC, Benbernou N, Esnault S, Guenounou M. Expression of IL-17 in human memory CD45RO+ T lymphocytes and its regulation by protein kinase A pathway. Cytokine. 1999;11:257–266. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasperska-Zajac A. Acute-phase response in chronic urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:665–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.