Abstract

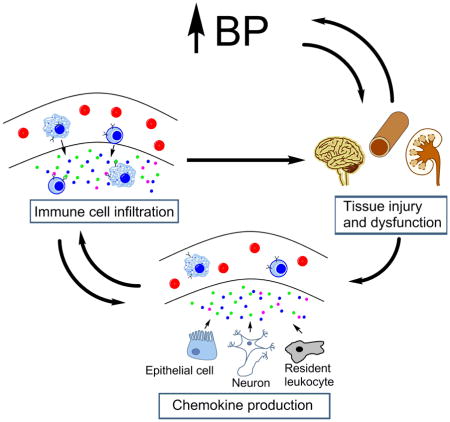

Immune cells infiltrate the kidney, vasculature, and central nervous system during hypertension, consequently amplifying tissue damage and/or blood pressure elevation. Mononuclear cell motility depends partly on chemokines, which are small cytokines that guide cells through an increasing concentration gradient via ligation of their receptors. Tissue expression of several chemokines is elevated in clinical and experimental hypertension. Likewise, immune cells have enhanced chemokine receptor expression during hypertension, driving immune cell infiltration and inappropriate inflammation in cardiovascular control centers. T lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages are pivotal mediators of hypertensive inflammation, and these cells migrate in response to several chemokines. As powerful drivers of diapedesis, the chemokines CCL2 and CCL5 have long been implicated in hypertension, but experimental data highlight divergent, context-specific effects of these chemokines on blood pressure and tissue injury. Several other chemokines, particularly those of the CXC family, contribute to blood pressure elevation and target organ damage. Given the significant interplay and chemotactic redundancy among chemokines during disease, future work must not only describe the actions of individual chemokines in hypertension, but also characterize how manipulating a single chemokine modulates the expression and/or function of other chemokines and their cognate receptors. This information will facilitate the design of precise chemotactic immunotherapies to limit cardiovascular and renal morbidity in hypertensive patients.

Keywords: Chemokines, Hypertension, Inflammation

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Accumulating evidence from pre-clinical experimental models indicates that misdirected immune responses contribute to the pathogenesis of hypertension. Inflammatory cells accumulate in cardiovascular control centers such as the kidney, vasculature, and brain where they precipitate tissue injury, hinder vascular relaxation, and promote sodium reabsorption. In human patients with hypertension, mononuclear cells similarly infiltrate the kidney and vasculature (1, 2). Accordingly, blocking lymphocyte proliferation or inhibiting the actions of a cytokine produced by lymphocytes and macrophages ameliorates clinical hypertension (3, 4). Thus, in experimental and human hypertension, cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems appear to drive blood pressure elevation via their recruitment into cardiovascular control tissues. Therefore, preventing the accumulation of these immune cells in cardiovascular control centers should inhibit local inflammatory injury and attenuate the hypertensive response. Indeed, genetic manipulations or pharmacological agents that abrogate the recruitment of immune cells, particularly monocytes/macrophages and T lymphocytes, into the vascular wall and kidney during hypertension reduce blood pressure and mitigate organ damage (5–8). However, global interruption of immune cell trafficking could lead to complications of immunosuppression including infection and even impaired tumor surveillance. The challenge is therefore to precisely manipulate the complex system that regulates immune cell migration to treat hypertension and its attendant cardiovascular consequences while preserving key immune defense mechanisms.

Immune cells patrol the circulatory system and peripheral tissues in search of invading pathogens. However, the profile of immune cell lineages varies dramatically between organs in health and disease. Specific migration of particular immune cell subpopulations is precisely governed by their expression of adhesion molecules that bind to receptors on the vascular endothelium and by tissue-specific gradients of chemotactic signals (9). Increased expression of specific chemokines within injured tissues directs the diapedesis of mononuclear cells across the vascular endothelium into the tissue parenchyma. Immune cells that harbor the cognate G protein-coupled chemokine receptors thereby follow the increasing concentration of chemokines to the tissue source. Approximately 50 chemokine ligands and 20 chemokine receptors have been characterized and are divided into four subgroups based on the spacing of conserved cysteine residues: CC, CXC, C, and CX3C (10). These abbreviations are followed by an “L” or “R” and a number to designate the ligand or receptor, respectively.

The majority of chemokines comprise the CC and CXC families, while only two C (XCL1 and XCL2) and one CX3C (CX3CL1) chemokines have been described. The expression pattern of chemokine ligands and receptors is determined by the tissue type and physiologic context (steady state vs. disease). For example, in steady state, lymphocytes home to peripheral lymphoid organs with high specificity. CCR7 on lymphocytes interacts with its chemokine ligands, CCL21 and CCL19, which are expressed on the high endothelial venules of lymph nodes to selectively promote the entry of lymphocytes from the circulation (11, 12). In the context of hypertension, the chemokines that drive the infiltration of immune cells, particularly T lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages, into the vasculature, kidney, and central nervous system (CNS) require further investigation. Although over 40 chemokine ligands have been described, two chemokines in particular, CCL2 and CCL5, have received the most scrutiny regarding their role in hypertension and target organ damage over the past two decades. More recently, studies have revealed important roles for CXC chemokines in this setting, while the function of C and CX3C chemokines in hypertension will require additional investigation. Pertinent studies of chemokines in hypertension, discussed herein, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies investigating the role of chemokines in hypertension

| Chemokine Ligand or Receptor | Method of Inhibition | Hypertensive Model | Effect on Blood Pressure | Effect on organ injury/dysfunction | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCR2 | Pharm – RS102895 | Ang II + high salt in rats | Transient ↓ | ↓ albuminuria and kidney fibrosis | 29 |

| Pharm – INCB3344 | DOCA-salt in mice | ↓ | Not measured | 30 | |

| Pharm – RS102895 | 2 kidney one clip in mice | ↑ | ↓ fibrosis and atrophy in Goldblatt kidney | 31 | |

| Genetic deletion | Ang II in mice | Not measured | ↓ vascular remodeling | 28 | |

| Genetic deletion | Ang II in mice | No effect | ↓ albuminuria and kidney damage; preserved GFR | 32 | |

| Genetic deletion | Ang II in mice | No effect | ↓ vascular remodeling | 33 | |

| CCL5 | Genetic deletion | Ang II in mice | No effect | ↑ Increased Albuminuria and augmented glomerular and interstitial injury | 35 |

| Pharm – met-RANTES; genetic deletion | Ang II in mice | No effect | ↓ ex vivo vascular dysfunction | 52 | |

| CCR5 | Genetic deletion | DOCA-salt + Ang II in mice | No effect | No effect on kidney or cardiac injury | 53 |

| CXCR2 | Pharm – SB265610; genetic deletion | DOCA-salt in mice; Ang II in mice | ↓ | ↓ vascular hypertrophy and fibrosis; preserved ex vivo vascular function | 71 |

| CXCR3 | Genetic deletion | Salt loading in mice | ↑ | Enhanced ex vivo vasoconstriction and blunted vasodilation | 66 |

| CXCR6 | Genetic deletion | Ang II in mice | No effect | ↓kidney injury and fibrosis | 70 |

| CXCL16 | Genetic deletion | DOCA-salt in mice; Ang II in mice | No effect | ↓kidney injury and fibrosis | 67, 68 |

| CX3CR1 | Genetic deletion | DOCA-salt in mice | No effect | ↓ kidney fibrosis | 77 |

CCL2

1 CCL2 (MCP-1) guides neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells to sites of inflammation via chemokine receptor ligation (13–15). Many cell types can secrete CCL2, including endothelial cells (16), vascular smooth muscle cells (17), renal tubular cells (18), and several cell lineages of the central nervous system – astrocytes, microglia, and neurons (19–21). Hypertensive detriments such as inflammation (22), mechanical stress on vessels (23), oxidative stress (24), and elevated angiotensin (Ang) II levels (25, 26) all elicit local CCL2 production. Consequently, T cells and monocytes, which harbor the primary CCL2 receptor, CCR2, infiltrate the tissue and exacerbate local inflammation, tissue injury, and hemodynamic dysfunction in hypertension.

Circulating levels of CCL2 are upregulated in patients with hypertension and correlate with the degree of hypertension-associated organ damage in humans (27). Furthermore, CCR2 protein expression on circulating monocytes is enhanced in hypertensive patients (28), leading to an enhanced sensitivity to CCL2 chemotaxis. In experimental models, the CCL2/CCR2 axis consistently exacerbates hypertensive tissue injury and inflammation. However, the effects on blood pressure of disrupting CCL2 signaling have varied with the experimental design. Pharmacological blockade of CCR2 slows the progression of, but does not ultimately reduce, established hypertension induced by a combination of angiotensin II infusion and high salt diet in rats (29). In mice, established hypertension caused by mineralocorticoid receptor activation in combination with salt loading is partially reversed by the administration of a CCR2 inhibitor (30). By contrast, CCL2 inhibition exacerbates renovascular hypertension, a model in which reduced perfusion to the clipped kidney drives renin secretion (31).

Unlike the use of pharmacological inhibitors, genetic deletion of CCR2 does not influence Ang II-dependent blood pressure elevation in mice (32, 33). These disparate results could be driven by a number of factors, including pharmacological, off-target effects that may drive phenotypic change not attributable to the intended action of the drug. Apart from technical issues, several chemokines are redundant in that they attract similar immune cell subpopulations through different receptors. CCR2 antagonists therefore may provide transient relief from immune-mediated elevations in blood pressure before compensation (i.e. the upregulation of redundant chemokines) occurs. This phenomenon of chemokine compensation has been described in allograft rejection (34), and our group has shown this to be the case in the progression of kidney fibrosis (35). On the other hand, mice harboring genetic deletion may have already offset the absence of CCR2 throughout development. As a result, CCR2-deficient mice may have enhanced expression of redundant chemokine ligands and/or receptors that compensate for the loss of CCR2 upon induction of experimental hypertension. Temporal measurements of several chemokine ligand/receptor axes in each model would reveal if this type of compensation occurs. Furthermore, it is conceivable that the reduced renal perfusion to the clipped kidney in renovascular hypertension model may have altered the renal trafficking of injurious and reparative macrophage populations leading to a disparate effect of CCL2 in this case.

CCL2 is upregulated in the hypertensive aorta and kidney (28, 36), whereas CCR2 expression is enhanced on circulating monocytes during hypertension (28). In the Ang II hypertension model, deficiency of CCR2 on bone marrow-derived cells alone attenuates macrophage infiltration and remodeling in the aorta (28, 33). In DOCA-salt hypertension, CCR2 inhibition reduces vascular accumulation of macrophages and lowers blood pressure (30). Thus, in multiple experimental models, CCL2/CCR2 signaling directs vascular accumulation of monocytes/macrophages with consequent local injury. In the hypertensive kidney, CCR2 similarly drives macrophage infiltration, local oxidative stress, glomerular injury, and ultimately loss of glomerular filtration rate during renin-angiotensin system (RAS) activation (29, 32). Accordingly, CCL2 inhibition attenuates macrophage infiltration and fibrosis in the Goldblatt hypertensive kidney (31). Collectively, these studies illustrate that local macrophage accumulation via the CCL2/CCR2 axis is a principal mediator of vascular remodeling and kidney injury in hypertension. In the circulation, high surface expression of CCR2 is predominantly found on pro-inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes (37). Therefore, CCR2 expression on the circulating monocyte largely favors tissue accumulation of pro-inflammatory rather than reparative macrophages in this setting.

The efficacy of RAS inhibition in large numbers of hypertensive patients suggests that the RAS is inappropriately activated in essential hypertension. The primary effector molecule of the RAS, Ang II, directly elicits CCL2 production in vascular and renal cells and enhances expression of CCR2 on monocytes (25, 26, 38, 39). In turn, global blockade of the type 1 angiotensin (AT1) receptor reduces CCR2 expression in circulating monocytes and CCL2 expression in aortic tissues during Ang II-dependent hypertension (28). Similarly, AT1 receptor blockade in the renovascular hypertension model limits the induction of CCL2 expression and macrophage infiltration in the glomeruli and renal interstitium (36). These studies reveal that AT1 receptor activation promotes CCL2-dependent vascular and kidney damage during hypertension. Our own experiments would suggest that AT1 receptors in the target organ mediate these injurious effects. We have reported that deleting AT1 receptors selectively in LysM-expressing macrophages enhances their polarization toward a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, increases their intrinsic expression of CCL2, and exaggerates tubulointerstitial damage to the kidney during RAS activation (40).

Stroke, or cerebrovascular accident, is among the most catastrophic complications of uncontrolled hypertension. While hypertension drives injury and inflammation in the brain, neuro-inflammation conversely also promotes autonomic signals that elevate blood pressure and encourage peripheral inflammation (41). The CCL2/CCR2 axis has been implicated in the translocation of inflammatory cells from the bone marrow to the CNS (42). For example, spontaneously hypertensive rats have elevated CCL2 in the bone marrow and an even higher concentration of CCL2 in cerebral spinal fluid compared to normotensive rats. This concentration gradient promotes the movement of CCR2-expressing myeloid cells into the CNS (43). Likewise, Sprague Dawley rats upregulate CCR2 on bone marrow cells in response to chronic Ang II infusion. Ang II is produced within the CNS, but circulating Ang II can also gain access to the CNS, as the blood brain barrier is often disrupted in hypertension (44). Moreover, Ang II can directly stimulate hypothalamic neurons to upregulate CCL2 production (43), thus driving recruitment of inflammatory cells, just as seen in the kidney and vasculature.

Immune cells also directly contribute to the local production of CCL2 in hypertensive tissues, leading to further recruitment of additional inflammatory cells. For example, T cells isolated from the aorta and kidney, but not the spleen and blood, of Ang II-infused mice produced more CCL2 upon T cell receptor stimulation compared to normotensive controls (45). Moreover, infiltrating T cells and monocytes/macrophages produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, that further induce CCL2 expression in resident tissue cells (46). Thus, in a positive feedback loop mediated via CCL2 and CCR2, the influx of immune cells instigates the recruitment of even more inflammatory cells that drives hypertensive organ damage and dysfunction.

CCL5

CCL5 (RANTES), much like CCL2, is a potent chemotactic molecule for monocytes and T cells that is produced by several tissues that control blood pressure, including vascular endothelium and smooth muscle (47, 48), glomeruli (49), renal tubules (50), and the CNS (51). CCL5 binds multiple chemokine receptors (CCR1, −3, and −5,). Likewise, CCR5 binds multiple chemokine ligands (CCL3, −4, and −5). However, in the context of hypertension, studies have focused on the interactions of CCL5 and its primary receptor, CCR5. Genetic deletion of CCL5 or CCR5 does not attenuate RAS-dependent hypertension, as CCL5-deficient and CCR5-deficient mice have similar blood pressure elevation as control mice during Ang II-induced hypertension (35, 52, 53). However, unlike CCL2, which consistently exacerbates tissue injury, the influence of CCL5 signaling on hypertensive organ damage appears to be tissue- and context-dependent. Moreover, although the majority of chemokine research pertains to immune cell recruitment, chemokines harbor alternative roles that could affect blood pressure and organ injury independent of inflammation. For example, CCL5 induces migration of endothelial progenitor cells during wound healing (54). Cataloguing non-inflammatory actions of chemokines will therefore be critical for elucidating how these molecules modulate target organ damage in hypertension.

CCL5 is upregulated in the aorta and perivascular adipose tissue (pVAT) during RAS-mediated hypertension, which coincides with an influx of myeloid cells and T cells into the pVAT, increased aortic superoxide production, and vascular dysfunction (5, 52). Genetic or pharmacological blockade of CCL5 signaling (CCL5-deficient mice and met-RANTES, respectively) blunts pVAT inflammation, reduces aortic superoxide production, and preserves vascular function without affecting blood pressure. In the CCL5-deficient mice, interferon-γ (IFNG)-producing T cells are preferentially excluded from the pVAT infiltrate during hypertension, suggesting that CCL5 may selectively recruit IFNG-producing T cells to the vasculature. IFNG has been shown to drive vascular oxidative stress and dysfunction and may therefore contribute to vascular pathology in RAS-dependent hypertension (55, 56).

Although CCL5 expression increases in the kidney during hypertension (53, 57), its effects on renal inflammation and injury appear to be protective. Without altering blood pressure elevation in response to chronic Ang II infusion, genetic deletion of CCL5 exacerbates urinary albumin excretion, glomerular injury, and interstitial fibrosis. Moreover, CCL5-deficient mice show enhanced macrophage accumulation in the kidney, accompanied by increased expression of TNF and IL-1β, two key drivers of RAS-dependent kidney injury. The protective effects of CCL5 on kidney injury have also been documented in other models of renal disease (58, 59). Therefore, the beneficial actions of CCL5 in hypertensive organ damage may be kidney-specific. During RAS activation, the exaggerated renal damage in the absence of CCL5 may accrue from local compensatory upregulation of CCL2. Accordingly, CCL2 blockade abrogates the enhanced renal macrophage infiltration and interstitial fibrosis in CCL5-deficient animals (35). These studies highlight the complex interactions between chemokines with overlapping specificities. Dissecting these interactions will be paramount to the careful development of immunomodulatory therapeutics for hypertensive patients.

2 CXC Chemokines

The CXC chemokines differ from the CC chemokines in structure, but share similar function, in that they guide the movement of cells via cognate receptor ligation. The CXC family has been implicated in immunity (10), angiogenesis (60), and cancer biology (61). However, the role of CXC chemokines in cardiovascular disease is relatively unknown. Highlighted below are initial investigations into the effects of CXC chemokine signaling in hypertension.

The expression of chemokine receptor CXCR3 has been reported on many leukocytes, but has been shown to be especially important in the migration of activated T cells, particularly pro-inflammatory Th1 T cells that propagate injury by secreting IFNG and TNF (62). Despite being a marker for pro-inflammatory T cells, CXCR3 may have unpredictable effects in renal disease as it also expressed on the immunosuppressive T regulatory cells that specifically temper the actions of Th1 cells (63). Three IFNG-inducible chemokine ligands bind CXCR3: CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11. These chemokines are produced by a wide variety of cell types, and circulating levels of all three are elevated in hypertensive patients (64, 65). Moreover, kidney biopsies from hypertensive patients show enhanced CXCL11 expression in the tubular epithelium, coupled with robust infiltration of T lymphocytes (64). These data would suggest that CXCR3 activity is amplified during human hypertension.

Nevertheless, in experimental models, CXCR3+ T cells limit rather than promote target organ damage accruing from hypertension. For example, CXCR3-deficient mice exhibit elevated baseline blood pressure, enhanced ex vivo vasoconstriction in response to Ang II, and blunted endothelium-dependent vasodilation compared to wild-type controls (66). These characteristics may be related to augmented AT1 receptor expression in the vasculature. The mechanisms through which CXCR3 activation limits AT1 receptor expression remain unclear. Interestingly we have found with microarray analysis that AT1 receptor activation on T cells suppresses their expression of CXCR3 and, in turn, limits the accumulation of Th1 lymphocytes in the kidney during hypertension (57). Thus, CXCR3 limits angiotensin receptor-mediated responses and Ang II suppresses CXCR3-dependent functions, providing another example of the complex “feedback” interactions between AT1 receptors on immune cells and the chemokine system.

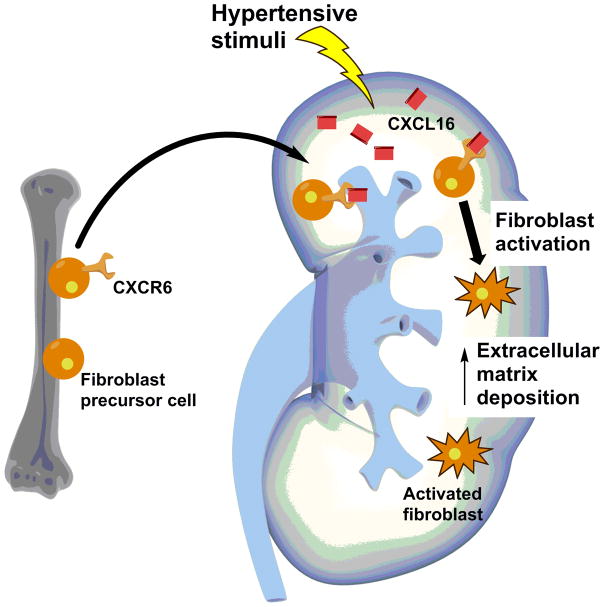

CXCL16 and its cognate receptor CXCR6 propagate hypertensive kidney injury. Renal expression of CXCL16 is upregulated in Ang II-induced and DOCA-salt hypertension (67, 68). In both hypertensive models, CXCL16-deficient mice have similar blood pressure to wild-type controls. However, the CXCL16-deficient kidneys are protected from T cell and macrophage infiltration, inflammation, injury, and fibrosis. CXCL16 was previously shown to enhance the recruitment of bone marrow-derived fibroblasts to the injured kidney in a model of renal fibrosis (69). In hypertension, CXCL16-deficient mice have similarly blunted accumulation of bone marrow-derived fibroblasts in the kidney, a plausible mechanism for the reduced renal fibrosis seen in these animals. The same group observed analogous results in the CXCR6-deficient mouse during chronic Ang II infusion (70), supporting the notion that CXCR6 signaling facilitates scar formation in the hypertensive kidney by driving recruitment of bone marrow-derived fibroblasts (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Bone marrow-derived fibroblasts may instigate fibrosis in the hypertensive kidney. Hypertension augments CXCL16 expression in the kidney. Bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursor cells that express the cognate CXCL16 receptor, CXCR6, infiltrate the kidney. Following activation, these fibroblasts deposit extracellular matrix that contributes to kidney dysfunction.

CXCR2 regulates neutrophil and myeloid cell motility through the binding of several CXC ligands, including CXCL1 through CXCL8. CXCR2-expressing leukocytes accumulate in the aorta during experimental hypertension, which coincides with vascular inflammation, dysfunction, and injury. Wang et al. recently employed genetic deletion and pharmacological blockade of CXCR2 to show that CXCR2 inhibition significantly attenuates Ang II-induced and DOCA-salt hypertension and associated vascular inflammation and injury (71). Bone marrow transplant studies using CXCR2-deficient mice confirmed that the deleterious effects of CXCR2 expression in hypertension were mediated by its actions on immune cells. Thus, CXCR2 signaling augments blood pressure elevation and consequent vascular injury in hypertension. Further studies will be required to understand whether CXCR2 secondarily raises blood pressure by instigating vascular injury or the converse.

3 C and CX3C chemokines

Limited data describe the chemotactic role of XCL1 and XCL2, and no studies to our knowledge have yet explored the role of the C chemokines in hypertension. However, XCL1 directs the movement of CD8+ dendritic cells (72), and dendritic cells play an important role in instigating blood pressure elevation (73). The function of XCL2 is largely unknown.

CX3CL1 (Fractalkine) exists in two forms: a membrane-anchored leukocyte adhesion molecule mainly expressed on endothelial cells or a soluble factor that attracts T cells and monocytes via the CX3CR1 receptor (74–76). In mice, DOCA-salt hypertension significantly increases CX3CL1 mRNA expression in whole kidney, and the protein localizes to tubular epithelial and vascular endothelial cells on immunohistochemistry (77). CX3CR1-deficient animals have a preserved hypertensive response, but are partially protected from renal fibrosis in this model. In these studies, CX3CL1 recruited F4/80-expressing myeloid cells into the kidney during hypertension. A similar pro-inflammatory effect of CX3CL1 was documented in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension (78).

4 Chemokines and immune cell differentiation

The myeloid and lymphoid compartments display remarkable phenotypic heterogeneity. Generally, M1 macrophages promote inflammation while M2 macrophages are reparative and anti-inflammatory. Th1 and Th17 T cells are thought to drive several immune-mediated pathologies, while T regulatory cells suppress inflammation. Thus, in hypertension, the extent of inflammatory tissue injury is largely attributed to the composition of local immune cell populations. Indeed, augmenting inflammatory or anti-inflammatory populations in vivo exacerbates or diminishes hypertensive pathology, respectively (79–82).

Beyond the canonical function of chemotaxis, chemokines influence immune cell differentiation. For example, in Leishmanial braziliensis infection, many monocytes that infiltrate the parasitic lesion differentiate into pro-inflammatory dendritic cells that are essential to resolve infection. The absence of CCR2 does not affect the recruitment of monocytes to lesions (83). However, CCR2-deficient monocytes showed blunted monocyte-to-dendritic cell conversion, leading to unresolved infection. Furthermore, T cell differentiation is heavily influenced by chemokines (84). For instance, CXCR3 not only guides T cells to sites of inflammation, but also affects CD8+ T cell differentiation (85, 86). Following antigen experience, CD8+ T cells lacking CXCR3 preferentially differentiate into memory cells, not short-lived effector cells, thus amplifying the memory pool. CD8+ memory T cells have been implicated in hypertension (87), and augmented memory T cell pools may explain why CXCR3-deficient mice experience exacerbated hypertensive pathology (66). Recent work also highlights the ability of T cells to trans-differentiate between subsets at sites of inflammation (88). Accordingly, chemokines may encourage hypertensive pathology not only by driving the infiltration of immune cells, but also by promoting differentiation of pro-inflammatory immune subsets in cardiovascular organs. This paradigm requires further investigation in the setting of hypertension.

5 Conclusion

Over 40 known chemokines have functions that are not mutually exclusive, can be promiscuous in receptor ligation, and appear to have divergent, tissue-specific functions in the setting of cardiovascular disease (Table 1). CCL5, for example, exacerbates vascular injury but protects the kidney in Ang II-induced hypertension. The exaggerated renal damage associated with CCL5-deficiency may culminate from tissue-specific compensation, whereby blockade of one chemokine upregulates expression of redundant chemokines that could actually worsen pathology. In our studies, genetic deletion of CCL5 results in the upregulation of renal CCL2 that exacerbates RAS-dependent inflammation and renal fibrosis (35). Background strain could also contribute to disparate actions of chemokines in murine experimental hypertension. CCL5-deficient mice on the C57BL/6 background are protected from vascular damage in hypertension, whereas CCL5-deficient mice on the 129SVE strain exhibit worse renal injury, suggesting that genetic background differences may impact chemokine signaling during disease. Such a finding complicates the direct application of experimental findings to the treatment of hypertension in a genetically diverse human population.

The subsets of immune cells recruited to hypertensive organs determine the inflammatory microenvironment. Although several chemokines, including CCL2, CCL5, and CX3CR1, attract both monocytes and T cells, the distinct subsets of monocytes and T cells guided by each chemokine may vary. For instance, circulating monocytes are categorized into two subsets – “patrolling/alternative” and “inflammatory” – that differentially express CCR2 and CX3CR1 (37). Moreover, T cells are parsed into at least four functionally distinct subsets that express chemokine receptors in a context-dependent manner (89). Inflammatory monocytes express abundant CCR2, are heavily recruited to sites of injury, and infiltrate the hypertensive vasculature and kidney (90). On the other hand, patrolling monocytes express high levels of CX3CR1 and are thought to be primarily reparative. However, CX3CR1 protects T cells from apoptosis and drives Th1 and Th17 cytokine production, which is known to exacerbate hypertensive pathology (91). Therefore, CCL2/CCR2 may exacerbate hypertensive pathology via the recruitment of pro-inflammatory monocytes, whereas CX3CL1/CX3CR1 can drive injury through Th1 and Th17 cytokine production.

Although myeloid and lymphoid populations drive hypertensive pathology, the exact subpopulations that mediate compartment-specific pathology require further study. For example, we have seen that altering T cell recruitment influences glomerular damage in the hypertensive kidney whereas modulating macrophage polarization and recruitment impacts tubulointerstitial injury (40, 57). Glomerulosclerosis is a relatively late finding in human hypertensive kidney disease, so it seems plausible that regulating the recruitment of pro-inflammatory T cells may be particularly helpful in patients with malignant hypertension and glomerular injury. By contrast, targeting myeloid cell recruitment to limit tubulointerstitial disease may benefit patients who are developing kidney fibrosis during hypertension. On the other hand, in acute kidney injury, macrophages exhibit shifting polarizations during different phases of disease pathogenesis (92), suggesting that immunomodulatory therapies may need to target different myeloid cell subsets at early versus later, more severe stages of hypertension. In several hypertensive models, chemokine inhibition modulated end organ damage without altering blood pressure. Clinically, chemokine therapy could supplement the standard regimen of blood pressure lowering treatments to further mitigate organ injury. Moreover, patients with resistant hypertension may benefit most from chemokine modulation. Given these uncertainties, further pre-clinical experiments coupled with descriptive clinical studies will need to pinpoint the specific inflammatory cell subsets that drive blood pressure elevation or hypertensive pathology. Subsequently, the configuration of chemokines that drive the infiltration or differentiation of these pro-hypertensive immune cells can potentially be regulated to safely attenuate end-organ damage in hypertensive patients.

Acknowledgments

NIH grants DK087893, HL128355; Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Grant BX000893; Duke O’Brien Center for Kidney Research

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hughson MD, Gobe GC, Hoy WE, Manning RD, Jr, Douglas-Denton R, Bertram JF. Associations of glomerular number and birth weight with clinicopathological features of African Americans and whites. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(1):18–28. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommers SC, Relman AS, Smithwick RH. Histologic studies of kidney biopsy specimens from patients with hypertension. Am J Pathol. 1958;34(4):685–715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrera J, Ferrebuz A, MacGregor EG, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Mycophenolate mofetil treatment improves hypertension in patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(12 Suppl 3):S218–225. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida S, Takeuchi T, Kotani T, Yamamoto N, Hata K, Nagai K, Shoda T, Takai S, Makino S, Hanafusa T. Infliximab, a TNF-alpha inhibitor, reduces 24-h ambulatory blood pressure in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;28(3):165–169. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2013.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204(10):2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenzel P, Knorr M, Kossmann S, Stratmann J, Hausding M, Schuhmacher S, Karbach SH, Schwenk M, Yogev N, Schulz E, Oelze M, Grabbe S, Jonuleit H, Becker C, Daiber A, Waisman A, Munzel T. Lysozyme M-positive monocytes mediate angiotensin II-induced arterial hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Circulation. 2011;124(12):1370–1381. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.034470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudemiller N, Lund H, Jacob HJ, Geurts AM, Mattson DL PhysGen Knockout P. CD247 modulates blood pressure by altering T-lymphocyte infiltration in the kidney. Hypertension. 2014;63(3):559–564. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMaster WG, Kirabo A, Madhur MS, Harrison DG. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertensive end-organ damage. Circ Res. 2015;116(6):1022–1033. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barreiro O, Martin P, Gonzalez-Amaro R, Sanchez-Madrid F. Molecular cues guiding inflammatory responses. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86(2):174–182. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith JW, Sokol CL, Luster AD. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: positioning cells for host defense and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:659–702. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Muller I, Wolf E, Lipp M. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forster R, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Rot A. CCR7 and its ligands: balancing immunity and tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(5):362–371. doi: 10.1038/nri2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuentes ME, Durham SK, Swerdel MR, Lewin AC, Barton DS, Megill JR, Bravo R, Lira SA. Controlled recruitment of monocytes and macrophages to specific organs through transgenic expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. J Immunol. 1995;155(12):5769–5776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charo IF, Ransohoff RM. The many roles of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):610–621. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston B, Burns AR, Suematsu M, Issekutz TB, Woodman RC, Kubes P. Chronic inflammation upregulates chemokine receptors and induces neutrophil migration to monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(9):1269–1276. doi: 10.1172/JCI5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sica A, Wang JM, Colotta F, Dejana E, Mantovani A, Oppenheim JJ, Larsen CG, Zachariae CO, Matsushima K. Monocyte chemotactic and activating factor gene expression induced in endothelial cells by IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor. J Immunol. 1990;144(8):3034–3038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang JM, Sica A, Peri G, Walter S, Padura IM, Libby P, Ceska M, Lindley I, Colotta F, Mantovani A. Expression of monocyte chemotactic protein and interleukin-8 by cytokine-activated human vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11(5):1166–1174. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.5.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prodjosudjadi W, Gerritsma JS, Klar-Mohamad N, Gerritsen AF, Bruijn JA, Daha MR, van Es LA. Production and cytokine-mediated regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by human proximal tubular epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 1995;48(5):1477–1486. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi M, Luo Y, Laning J, Strieter RM, Dorf ME. Production and function of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and other beta-chemokines in murine glial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1995;60(1–2):143–150. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson PK, Hu S, Salak-Johnson J, Molitor TW, Chao CC. Differential production of and migratory response to beta chemokines by human microglia and astrocytes. J Infect Dis. 1997;175(2):478–481. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banisadr G, Gosselin RD, Mechighel P, Kitabgi P, Rostene W, Parsadaniantz SM. Highly regionalized neuronal expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) in rat brain: evidence for its colocalization with neurotransmitters and neuropeptides. J Comp Neurol. 2005;489(3):275–292. doi: 10.1002/cne.20598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rollins BJ. Chemokines. Blood. 1997;90(3):909–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shyy YJ, Hsieh HJ, Usami S, Chien S. Fluid shear stress induces a biphasic response of human monocyte chemotactic protein 1 gene expression in vascular endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(11):4678–4682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lakshminarayanan V, Beno DW, Costa RH, Roebuck KA. Differential regulation of interleukin-8 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 by H2O2 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in endothelial and epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(52):32910–32918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capers Qt, Alexander RW, Lou P, De Leon H, Wilcox JN, Ishizaka N, Howard AB, Taylor WR. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in aortic tissues of hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1997;30(6):1397–1402. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen XL, Tummala PE, Olbrych MT, Alexander RW, Medford RM. Angiotensin II induces monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene expression in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1998;83(9):952–959. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.9.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tucci M, Quatraro C, Frassanito MA, Silvestris F. Deregulated expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in arterial hypertension: role in endothelial inflammation and atheromasia. J Hypertens. 2006;24(7):1307–1318. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000234111.31239.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishibashi M, Hiasa K, Zhao Q, Inoue S, Ohtani K, Kitamoto S, Tsuchihashi M, Sugaya T, Charo IF, Kura S, Tsuzuki T, Ishibashi T, Takeshita A, Egashira K. Critical role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor CCR2 on monocytes in hypertension-induced vascular inflammation and remodeling. Circ Res. 2004;94(9):1203–1210. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126924.23467.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elmarakby AA, Quigley JE, Olearczyk JJ, Sridhar A, Cook AK, Inscho EW, Pollock DM, Imig JD. Chemokine receptor 2b inhibition provides renal protection in angiotensin II - salt hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;50(6):1069–1076. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan CT, Moore JP, Budzyn K, Guida E, Diep H, Vinh A, Jones ES, Widdop RE, Armitage JA, Sakkal S, Ricardo SD, Sobey CG, Drummond GR. Reversal of vascular macrophage accumulation and hypertension by a CCR2 antagonist in deoxycorticosterone/salt-treated mice. Hypertension. 2012;60(5):1207–1212. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.201251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kashyap S, Warner GM, Hartono SP, Boyilla R, Knudsen BE, Zubair AS, Lien K, Nath KA, Textor SC, Lerman LO, Grande JP. Blockade of CCR2 reduces macrophage influx and development of chronic renal damage in murine renovascular hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310(5):F372–384. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00131.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao TD, Yang XP, Liu YH, Shesely EG, Cavasin MA, Kuziel WA, Pagano PJ, Carretero OA. Role of inflammation in the development of renal damage and dysfunction in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;52(2):256–263. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.112706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bush E, Maeda N, Kuziel WA, Dawson TC, Wilcox JN, DeLeon H, Taylor WR. CC chemokine receptor 2 is required for macrophage infiltration and vascular hypertrophy in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;36(3):360–363. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnickel GT, Bastani S, Hsieh GR, Shefizadeh A, Bhatia R, Fishbein MC, Belperio J, Ardehali A. Combined CXCR3/CCR5 blockade attenuates acute and chronic rejection. J Immunol. 2008;180(7):4714–4721. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudemiller NP, Patel MB, Zhang JD, Jeffs AD, Karlovich NS, Griffiths R, Kan MJ, Buckley AF, Gunn MD, Crowley SD. C-C Motif Chemokine 5 Attenuates Angiotensin II-Dependent Kidney Injury by Limiting Renal Macrophage Infiltration. Am J Pathol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hilgers KF, Hartner A, Porst M, Mai M, Wittmann M, Hugo C, Ganten D, Geiger H, Veelken R, Mann JF. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and macrophage infiltration in hypertensive kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2000;58(6):2408–2419. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(11):762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruiz-Ortega M, Ruperez M, Lorenzo O, Esteban V, Blanco J, Mezzano S, Egido J. Angiotensin II regulates the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the kidney. Kidney Int Suppl. 2002;(82):S12–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.62.s82.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morita T, Imai T, Yamaguchi T, Sugiyama T, Katayama S, Yoshino G. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 in monocytes suppresses angiotensin II-elicited chemotactic activity through inhibition of CCR2: role of bilirubin and carbon monoxide generated by the enzyme. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5(4):439–447. doi: 10.1089/152308603768295186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang JD, Patel MB, Griffiths R, Dolber PC, Ruiz P, Sparks MA, Stegbauer J, Jin H, Gomez JA, Buckley AF, Lefler WS, Chen D, Crowley SD. Type 1 angiotensin receptors on macrophages ameliorate IL-1 receptor-mediated kidney fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(5):2198–2203. doi: 10.1172/JCI61368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, McCann LA, Weyand C, Gordon FJ, Harrison DG. Central and peripheral mechanisms of T-lymphocyte activation and vascular inflammation produced by angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;107(2):263–270. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ataka K, Asakawa A, Nagaishi K, Kaimoto K, Sawada A, Hayakawa Y, Tatezawa R, Inui A, Fujimiya M. Bone marrow-derived microglia infiltrate into the paraventricular nucleus of chronic psychological stress-loaded mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e81744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santisteban MM, Ahmari N, Carvajal JM, Zingler MB, Qi Y, Kim S, Joseph J, Garcia-Pereira F, Johnson RD, Shenoy V, Raizada MK, Zubcevic J. Involvement of bone marrow cells and neuroinflammation in hypertension. Circ Res. 2015;117(2):178–191. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biancardi VC, Son SJ, Ahmadi S, Filosa JA, Stern JE. Circulating angiotensin II gains access to the hypothalamus and brain stem during hypertension via breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. Hypertension. 2014;63(3):572–579. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei Z, Spizzo I, Diep H, Drummond GR, Widdop RE, Vinh A. Differential phenotypes of tissue-infiltrating T cells during angiotensin II-induced hypertension in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho AW, Wong CK, Lam CW. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha up-regulates the expression of CCL2 and adhesion molecules of human proximal tubular epithelial cells through MAPK signaling pathways. Immunobiology. 2008;213(7):533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jordan NJ, Watson ML, Williams RJ, Roach AG, Yoshimura T, Westwick J. Chemokine production by human vascular smooth muscle cells: modulation by IL-13. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122(4):749–757. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laubli H, Spanaus KS, Borsig L. Selectin-mediated activation of endothelial cells induces expression of CCL5 and promotes metastasis through recruitment of monocytes. Blood. 2009;114(20):4583–4591. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-186585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolf G, Ziyadeh FN, Thaiss F, Tomaszewski J, Caron RJ, Wenzel U, Zahner G, Helmchen U, Stahl RA. Angiotensin II stimulates expression of the chemokine RANTES in rat glomerular endothelial cells. Role of the angiotensin type 2 receptor. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(5):1047–1058. doi: 10.1172/JCI119615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wada T, Furuichi K, Segawa-Takaeda C, Shimizu M, Sakai N, Takeda SI, Takasawa K, Kida H, Kobayashi KI, Mukaida N, Ohmoto Y, Matsushima K, Yokoyama H. MIP-1alpha and MCP-1 contribute to crescents and interstitial lesions in human crescentic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1999;56(3):995–1003. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gouraud SS, Waki H, Bhuiyan ME, Takagishi M, Cui H, Kohsaka A, Paton JF, Maeda M. Down-regulation of chemokine Ccl5 gene expression in the NTS of SHR may be pro-hypertensive. J Hypertens. 2011;29(4):732–740. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328344224d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mikolajczyk TP, Nosalski R, Szczepaniak P, Budzyn K, Osmenda G, Skiba D, Sagan A, Wu J, Vinh A, Marvar PJ, Guzik B, Podolec J, Drummond G, Lob HE, Harrison DG, Guzik TJ. Role of chemokine RANTES in the regulation of perivascular inflammation, T-cell accumulation, and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. The FASEB Journal. 2016 doi: 10.1096/fj.201500088R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krebs C, Fraune C, Schmidt-Haupt R, Turner JE, Panzer U, Quang MN, Tannapfel A, Velden J, Stahl RA, Wenzel UO. CCR5 deficiency does not reduce hypertensive end-organ damage in mice. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25(4):479–486. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishida Y, Kimura A, Kuninaka Y, Inui M, Matsushima K, Mukaida N, Kondo T. Pivotal role of the CCL5/CCR5 interaction for recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells in mouse wound healing. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(2):711–721. doi: 10.1172/JCI43027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kossmann S, Schwenk M, Hausding M, Karbach SH, Schmidgen MI, Brandt M, Knorr M, Hu H, Kroller-Schon S, Schonfelder T, Grabbe S, Oelze M, Daiber A, Munzel T, Becker C, Wenzel P. Angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction depends on interferon-gamma-driven immune cell recruitment and mutual activation of monocytes and NK-cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(6):1313–1319. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manea SA, Todirita A, Raicu M, Manea A. C/EBP transcription factors regulate NADPH oxidase in human aortic smooth muscle cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18(7):1467–1477. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang JD, Patel MB, Song YS, Griffiths R, Burchette J, Ruiz P, Sparks MA, Yan M, Howell DN, Gomez JA, Spurney RF, Coffman TM, Crowley SD. A novel role for type 1 angiotensin receptors on T lymphocytes to limit target organ damage in hypertension. Circ Res. 2012;110(12):1604–1617. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anders HJ, Frink M, Linde Y, Banas B, Wornle M, Cohen CD, Vielhauer V, Nelson PJ, Grone HJ, Schlondorff D. CC chemokine ligand 5/RANTES chemokine antagonists aggravate glomerulonephritis despite reduction of glomerular leukocyte infiltration. J Immunol. 2003;170(11):5658–5666. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lloyd CM, Dorf ME, Proudfoot A, Salant DJ, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. Role of MCP-1 and RANTES in inflammation and progression to fibrosis during murine crescentic nephritis. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62(5):676–680. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.5.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Belperio JA, Keane MP, Arenberg DA, Addison CL, Ehlert JE, Burdick MD, Strieter RM. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vandercappellen J, Van Damme J, Struyf S. The role of CXC chemokines and their receptors in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;267(2):226–244. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qin S, Rottman JB, Myers P, Kassam N, Weinblatt M, Loetscher M, Koch AE, Moser B, Mackay CR. The chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CCR5 mark subsets of T cells associated with certain inflammatory reactions. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(4):746–754. doi: 10.1172/JCI1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paust HJ, Riedel JH, Krebs CF, Turner JE, Brix SR, Krohn S, Velden J, Wiech T, Kaffke A, Peters A, Bennstein SB, Kapffer S, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Wegscheid C, Tiegs G, Thaiss F, Mittrucker HW, Steinmetz OM, Stahl RA, Panzer U. CXCR3+ Regulatory T Cells Control TH1 Responses in Crescentic GN. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(7):1933–1942. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015020203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Youn JC, Yu HT, Lim BJ, Koh MJ, Lee J, Chang DY, Choi YS, Lee SH, Kang SM, Jang Y, Yoo OJ, Shin EC, Park S. Immunosenescent CD8+ T cells and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 3 chemokines are increased in human hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;62(1):126–133. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.00689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stumpf C, Auer C, Yilmaz A, Lewczuk P, Klinghammer L, Schneider M, Daniel WG, Schmieder RE, Garlichs CD. Serum levels of the Th1 chemoattractant interferon-gamma-inducible protein (IP) 10 are elevated in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2011;34(4):484–488. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hsu HH, Duning K, Meyer HH, Stolting M, Weide T, Kreusser S, van Le T, Gerard C, Telgmann R, Brand-Herrmann SM, Pavenstadt H, Bek MJ. Hypertension in mice lacking the CXCR3 chemokine receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296(4):F780–789. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90444.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liang H, Ma Z, Peng H, He L, Hu Z, Wang Y. CXCL16 Deficiency Attenuates Renal Injury and Fibrosis in Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28715. doi: 10.1038/srep28715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xia Y, Entman ML, Wang Y. Critical role of CXCL16 in hypertensive kidney injury and fibrosis. Hypertension. 2013;62(6):1129–1137. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen G, Lin SC, Chen J, He L, Dong F, Xu J, Han S, Du J, Entman ML, Wang Y. CXCL16 recruits bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursors in renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(10):1876–1886. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xia Y, Jin X, Yan J, Entman ML, Wang Y. CXCR6 plays a critical role in angiotensin II-induced renal injury and fibrosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(7):1422–1428. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.303172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang L, Zhao XC, Cui W, Ma YQ, Ren HL, Zhou X, Fassett J, Yang YZ, Chen Y, Xia YL, Du J, Li H. Genetic and Pharmacologic Inhibition of the Chemokine Receptor CXCR2 Prevents Experimental Hypertension and Vascular Dysfunction. Circulation. 2016 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dorner BG, Dorner MB, Zhou X, Opitz C, Mora A, Guttler S, Hutloff A, Mages HW, Ranke K, Schaefer M, Jack RS, Henn V, Kroczek RA. Selective expression of the chemokine receptor XCR1 on cross-presenting dendritic cells determines cooperation with CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;31(5):823–833. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kirabo A, Fontana V, de Faria AP, Loperena R, Galindo CL, Wu J, Bikineyeva AT, Dikalov S, Xiao L, Chen W, Saleh MA, Trott DW, Itani HA, Vinh A, Amarnath V, Amarnath K, Guzik TJ, Bernstein KE, Shen XZ, Shyr Y, Chen SC, Mernaugh RL, Laffer CL, Elijovich F, Davies SS, Moreno H, Madhur MS, Roberts J, 2nd, Harrison DG. DC isoketal-modified proteins activate T cells and promote hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(10):4642–4656. doi: 10.1172/JCI74084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bazan JF, Bacon KB, Hardiman G, Wang W, Soo K, Rossi D, Greaves DR, Zlotnik A, Schall TJ. A new class of membrane-bound chemokine with a CX3C motif. Nature. 1997;385(6617):640–644. doi: 10.1038/385640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fraticelli P, Sironi M, Bianchi G, D’Ambrosio D, Albanesi C, Stoppacciaro A, Chieppa M, Allavena P, Ruco L, Girolomoni G, Sinigaglia F, Vecchi A, Mantovani A. Fractalkine (CX3CL1) as an amplification circuit of polarized Th1 responses. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(9):1173–1181. doi: 10.1172/JCI11517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Imai T, Hieshima K, Haskell C, Baba M, Nagira M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Takagi S, Nomiyama H, Schall TJ, Yoshie O. Identification and molecular characterization of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1, which mediates both leukocyte migration and adhesion. Cell. 1997;91(4):521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shimizu K, Furuichi K, Sakai N, Kitagawa K, Matsushima K, Mukaida N, Kaneko S, Wada T. Fractalkine and its receptor, CX3CR1, promote hypertensive interstitial fibrosis in the kidney. Hypertens Res. 2011;34(6):747–752. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Balabanian K, Foussat A, Dorfmuller P, Durand-Gasselin I, Capel F, Bouchet-Delbos L, Portier A, Marfaing-Koka A, Krzysiek R, Rimaniol AC, Simonneau G, Emilie D, Humbert M. CX(3)C chemokine fractalkine in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(10):1419–1425. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2106007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barhoumi T, Kasal DA, Li MW, Shbat L, Laurant P, Neves MF, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Hypertension. 2011;57(3):469–476. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shah KH, Shi P, Giani JF, Janjulia T, Bernstein EA, Li Y, Zhao T, Harrison DG, Bernstein KE, Shen XZ. Myeloid Suppressor Cells Accumulate and Regulate Blood Pressure in Hypertension. Circ Res. 2015;117(10):858–869. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trott DW, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Saleh MA, Itani H, Norlander AE, Wu J, Goldstein A, Arendshorst WJ, Madhur MS, Chen W, Li CI, Shyr Y, Harrison DG. Oligoclonal CD8+ T cells play a critical role in the development of hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;64(5):1108–1115. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kasal DA, Barhoumi T, Li MW, Yamamoto N, Zdanovich E, Rehman A, Neves MF, Laurant P, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent aldosterone-induced vascular injury. Hypertension. 2012;59(2):324–330. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.181123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Costa DL, Lima-Junior DS, Nascimento MS, Sacramento LA, Almeida RP, Carregaro V, Silva JS. CCR2 signaling contributes to the differentiation of protective inflammatory dendritic cells in Leishmania braziliensis infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100(2):423–432. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4A0715-288R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Luther SA, Cyster JG. Chemokines as regulators of T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(2):102–107. doi: 10.1038/84205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kurachi M, Kurachi J, Suenaga F, Tsukui T, Abe J, Ueha S, Tomura M, Sugihara K, Takamura S, Kakimi K, Matsushima K. Chemokine receptor CXCR3 facilitates CD8(+) T cell differentiation into short-lived effector cells leading to memory degeneration. J Exp Med. 2011;208(8):1605–1620. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hu JK, Kagari T, Clingan JM, Matloubian M. Expression of chemokine receptor CXCR3 on T cells affects the balance between effector and memory CD8 T-cell generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(21):E118–127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101881108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Itani HA, Xiao L, Saleh MA, Wu J, Pilkinton MA, Dale BL, Barbaro NR, Foss JD, Kirabo A, Montaniel KR, Norlander AE, Chen W, Sato R, Navar LG, Mallal SA, Madhur MS, Bernstein KE, Harrison DG. CD70 Exacerbates Blood Pressure Elevation and Renal Damage in Response to Repeated Hypertensive Stimuli. Circ Res. 2016 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.308111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Komatsu N, Okamoto K, Sawa S, Nakashima T, Oh-hora M, Kodama T, Tanaka S, Bluestone JA, Takayanagi H. Pathogenic conversion of Foxp3+ T cells into TH17 cells in autoimmune arthritis. Nat Med. 2014;20(1):62–68. doi: 10.1038/nm.3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reiner SL. Decision making during the conception and career of CD4+ T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(2):81–82. doi: 10.1038/nri2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kossmann S, Hu H, Steven S, Schonfelder T, Fraccarollo D, Mikhed Y, Brahler M, Knorr M, Brandt M, Karbach SH, Becker C, Oelze M, Bauersachs J, Widder J, Munzel T, Daiber A, Wenzel P. Inflammatory monocytes determine endothelial nitric-oxide synthase uncoupling and nitro-oxidative stress induced by angiotensin II. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(40):27540–27550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.604231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dong L, Nordlohne J, Ge S, Hertel B, Melk A, Rong S, Haller H, von Vietinghoff S. T Cell CX3CR1 Mediates Excess Atherosclerotic Inflammation in Renal Impairment. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(6):1753–1764. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee S, Huen S, Nishio H, Nishio S, Lee HK, Choi BS, Ruhrberg C, Cantley LG. Distinct macrophage phenotypes contribute to kidney injury and repair. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(2):317–326. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009060615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]