Abstract

Introduction

The association between cigarette smoking and erectile dysfunction has been well established. Studies demonstrate improvements in erectile rigidity and tumescence as a result of smoking cessation. Radical prostatectomy is also associated with worsening of erectile function secondary to damage to the neurovascular bundles. To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the relationship between smoking cessation after prostate cancer diagnosis and its effect on sexual function following robotic prostatectomy. We sought to demonstrate the utility of a smoking cessation program among patients with prostate cancer who planned to undergo robotic prostatectomy at Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

Methods

All patients who underwent robotic prostatectomy between March 2011 and April 2013 with known smoking status were included, and were followed-up through November 2014. All smokers were offered the smoking cessation program, which included wellness coaching, tobacco cessation classes, and pharmacotherapy. Patients completed the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite-26 (EPIC-26) health-related quality-of-life (HR-QOL) survey at baseline and postoperatively at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. There were 2 groups based on smoking status: Continued smoking vs quitting group. Patient’s age, Charlson Comorbidity Score, body mass index, educational level, median household income, family history of prostate cancer, race/ethnicity, language, nerve-sparing status, and preoperative/postoperative clinicopathology and EPIC-26 HR-QOL scores were examined. A linear regression model was used to predict sexual function recovery.

Results

A total of 139 patients identified as smokers underwent the smoking cessation program and completed the EPIC-26 surveys. Fifty-six patients quit smoking, whereas 83 remained smokers at last follow-up. All demographics and clinicopathology were matched between the 2 cohorts. Smoking cessation, along with bilateral nerve-sparing status, were the only 2 modifiable factors associated with improved sexual function after prostatectomy (6.57 points, p = 0.0226 and 8.97 points, p = 0.0485, respectively).

Conclusion

In the setting of robotic prostatectomy, perioperative smoking cessation is associated with a significant improvement in long-term sexual functional outcome when other factors are adjusted.

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 42.1 million US adults currently smoke cigarettes.1 Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the US. From a surgical standpoint, cigarette smoking substantially increases risk of complications. In the perioperative setting, smoker status inhibits overall recovery and increases risk of pulmonary and wound complications.2 The association between cigarette smoking and erectile dysfunction (ED) also has been well established. Even after controlling for age and cardiovascular risk factors, chronic smokers are 1.5 to 2 times more likely to experience ED than nonsmokers.3–8 Studies demonstrate improvements in erectile rigidity and tumescence as a result of smoking cessation.9–11 The literature also demonstrates that presurgical smoking cessation reduces perioperative complications and improves long-term outcomes.12–15

Radical prostatectomy is associated with worsening of erectile function secondary to damage to the neurovascular bundles.16 To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the relationship between smoking cessation after prostate cancer diagnosis and its effect on sexual function following robotic prostatectomy. We sought to demonstrate the utility of a smoking cessation program among patients with prostate cancer who planned to undergo robotic prostatectomy in our health care system.

METHODS

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC). All patients who underwent robotic radical prostatectomy between March 2011 and April 2013 in the KPSC Region and had known positive smoking status were retrospectively reviewed. Follow-up data were available through November 2014. All robotic prostatectomies were performed by 20 experienced, high-volume, fellowship-trained robotic surgeons operating at 4 Medical Centers. All surgeons had completed at least 100 robotic prostatectomies before being enrolled in a cohort. All patients in our health care system who received care from any medical specialty at any of our institution’s facilities were asked about their smoking status by ancillary staff at the point of care. When identified as a current smoker, patients were offered access to smoking cessation resources that included a wellness coach, tobacco cessation classes, and pharmacotherapy.

This protocol was standardized among all the facilities within KPSC. Pharmacotherapy included nicotine replacement therapy and bupropion and varenicline administered at the discretion of the prescribing physician. Presurgical sexual function was assessed via the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite-26 (EPIC-26) health-related quality-of-life (HR-QOL) survey, a standardized questionnaire designed to assess quality of life among patients with prostate cancer (see Figure 1 available online at www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2017/16-138-Figure-1.pdf).17 The survey is standardized on a 0–100 scale, with higher scores corresponding to better quality of life. Patients completed the EPIC-26 HR-QOL before surgery; during postsurgical recovery; and at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. For the purposes of this study, we focused specifically on the sexual function domain. All patients were considered smokers at baseline. As they quit, they were moved to the quit smoking group. Cross-sectional sexual domain scores were obtained and data were analyzed as an intercept of the conglomerate sexual domain scores at their respective time points. Patients underwent postsurgical penile rehabilitation consisting of a combination of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors and a vacuum erection device, which were offered at the discretion of individual surgeons. Patient age at diagnosis, prostate-specific antigen level, Charlson Comorbidity Score, body mass index, race/ethnicity, EPIC-26 HR-QOL scores, nerve-sparing status, and presurgical/postsurgical clinicopathology were examined. A linear regression model was used to predict sexual function recovery.

RESULTS

Between March 2011 and April 2013, 2514 patients underwent robotic prostatectomy. Among these men, 139 were identified as smokers and underwent the formal smoking cessation program. Fifty-six patients quit smoking during the study, and 83 remained smokers at last follow-up. Of the 139 men smokers at baseline, 94 completed the baseline EPIC-26 HR-QOL survey. Fifty-two smokers and 10 who quit completed the 1-month survey, 54 smokers and 18 who quit completed the 3-month survey, 44 smokers and 20 who quit completed the 6-month survey, 38 smokers and 18 who quit completed the 12-month survey, 21 smokers and 18 who quit completed the 18-month survey, and 20 smokers and 8 who quit completed the 24-month survey. All demographics and clinicopathology were statistically similar between the 2 cohorts (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Multivariate analysis comparing the demographics and clinicopathology between the continued-smoking and quit-smoking groups

| Factors | Continued smoking (n = 83) | Quit smoking (n = 56) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 59.1 | 60.2 | 0.3635 |

| Mean prostate-specific antigen score | 7.7 | 7.9 | 0.4127 |

| Gleason score, no. (%) | |||

| Missing | 3 (3.6) | 2 (3.6) | 0.4665 |

| 6 | 38 (45.8) | 28 (50) | |

| 7 | 31 (37.3) | 22 (39.3) | |

| 8 | 9 (10.8) | 2 (3.6) | |

| 9 | 2 (2.4) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Charlson comorbidity score, no. (%) | |||

| 0 | 53 (63.9) | 35 (62.5) | 0.6032 |

| 1 | 13 (15.7) | 12 (21.4) | |

| 2 | 10 (12.0) | 7 (12.5) | |

| 3+ | 7 (8.4) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Mean body mass index | 27.1 | 28.0 | 0.3023 |

| Race/ethnicity, no. (%) | |||

| White | 33 (39.8) | 17 (30.4) | 0.6487 |

| Black | 16 (19.3) | 17 (30.4) | |

| Hispanic | 25 (30.1) | 16 (28.6) | |

| Asian | 5 (6.0) | 3 (5.4) | |

| Other/unknown | 4 (4.8) | 3 (5.4) | |

| Nerve-sparing status, no. (%) | |||

| Missing | 4 (4.8) | 1 (1.8) | 0.0998 |

| None | 10 (12.0) | 7 (12.5) | |

| Unilateral | 6 (7.2) | 11 (19.6) | |

| Bilateral | 63 (75.9) | 37 (66.1) | |

Table 2.

Pathologic features of the continued-smoking and quit-smoking groups based on the tumor, nodes, and metastasis staging system (p = 0.1344)

| Clinical stage | Continued smoking (n = 83), no. (%) | Quit smoking (n = 56), no. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| T2a | 7 (8) | 3 (5) |

| T2b | 2 (2) | 3 (5) |

| T2c | 49 (59) | 21 (38) |

| T3a | 12 (14) | 20 (36) |

| T3b | 13 (16) | 9 (16) |

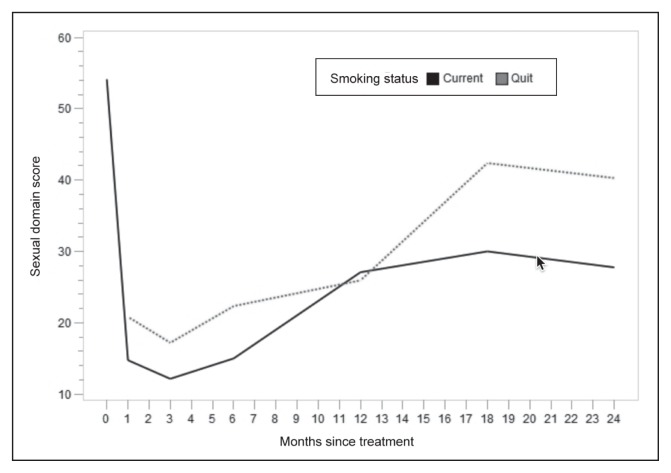

The mean EPIC-26 HR-QOL sexual function scores at each time point are listed in Table 3 and depicted in graph form in Figure 2. A linear regression model was used to assess the association of smoking with EPIC-26 HR-QOL sexual function scores, adjusting for age, Charlson Comorbidity score, and nerve-sparing status, all of which were deemed significant variables with regard to recovery of sexual function (Table 4). As expected, age was associated with a statistically significant improvement in mean sexual function scores. Smoking cessation and bilateral nerve-sparing status were the only modifiable factors associated with increased sexual function after prostatectomy (6.57 points, p = 0.0226 and 8.97 points, p = 0.0485, respectively).

Table 3.

Mean EPIC-26 HR-QOL sexual function domain scores for quit-smoking and continued-smoking groups by time from diagnosis of prostate cancer

| Time point (mos) | Quit smoking | Continued smoking | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean score | n | Mean score | |

| Baseline, n = 94, mean score = 54.1 | — | — | — | — |

| 1 | 10 | 20.8 | 52 | 14.8 |

| 3 | 18 | 17.2 | 54 | 12.2 |

| 6 | 20 | 22.4 | 44 | 15.0 |

| 12 | 18 | 26.0 | 38 | 27.1 |

| 18 | 18 | 42.4 | 21 | 30.1 |

| 24 | 8 | 40.3 | 20 | 27.8 |

EPIC-26 HR-QOL = expanded prostate cancer index composite health-related quality-of-life short form.

Figure 2.

EPIC-26 HR-QOL sexual domain scores by smoking status.

EPIC-26 HR-QOL = expanded prostate cancer index composite health-related quality-of-life short form.

Table 4.

Linear regression model assessing the association of smoking with EPIC-26 HR-QOL sexual function scores and adjusting for age, Charlson Comorbidity score, and nerve-sparing status: Model of association with sexual domain score posttreatment

| Parameter | Estimate | 95% confidence limits | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quit smoking | 6.5744 | 0.9250 | 12.2238 | 0.0226 |

| Age | −0.6167 | −1.0806 | −0.1528 | 0.0092 |

| Charlson Comorbidity score | 1.1857 | −1.2946 | 3.6660 | 0.3488 |

| Nerve-sparing, unilateral vs no | 0.7254 | −9.5394 | 10.9902 | 0.8898 |

| Nerve-sparing, bilateral vs no | 8.9684 | 0.0585 | 17.8783 | 0.0485 |

EPIC-26 HR-QOL = expanded prostate cancer index composite health-related quality-of-life short form.

DISCUSSION

Cigarette smoking has been associated with increased risk of perioperative complications across multiple surgical specialties.18 In a large retrospective cohort reviewing the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, Turan et al19 reported that current smokers were more likely to experience pneumonia, unplanned intubation, mechanical ventilation, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, stroke, superficial and deep incisional infections, organ-space infections, sepsis, and septic shock. Furthermore, current smokers were 1.38 times more likely to die than never-smokers.19 According to Krueger et al,18 smokers undergoing plastic surgery are at increased risk for wound infections, reduced skin flap survival, and lower rates of successful digital reimplantation. Investigators performed a systematic review of 6 randomized trials to examine the effect of smoking cessation on postsurgical complications, and the authors reported a relative risk reduction of 41% for prevention of postsurgical complications.2 Longer periods of cessation were associated with a larger reduction in the complication rate.2

In addition to its deleterious effects in the perioperative setting, smoker status also is an independent risk factor for ED. A study involving a cohort of 1329 men demonstrated that the likelihood of ED was higher among those who had ever smoked (ie, current or former smokers) vs never-smokers.20 A prospective study examining ED risk factors reported a statistically significant decreased risk of ED among former smokers vs those who continued to smoke (current smoker risk ratio, 1.5; past smoker risk ratio, 1.2).21 Never-smokers had the lowest rate of ED in this study. These studies demonstrate evidence of a dose response with regard to the number of smoking-pack years to sexual functional recovery. One study concluded that quitting smoking significantly enhances both physiologic and patient-reported indices of sexual health, regardless of baseline erectile function.10 Other authors have demonstrated improvements in penile blood flow and/or penile tumescence/rigidity with only 24 to 36 hours of smoking cessation.9,22

The quality of spared nerves, patient age, and baseline sexual function are the most meaningful prognostic factors when attempting to predict postsurgical erectile function.23–26 Our results suggest that perioperative smoking cessation improves sexual function after prostatectomy. In addition to nerve-sparing status, smoking cessation is the most influential modifiable factor in improving postsurgical sexual function recovery when all variables are adjusted. Those who quit smoking scored 6.57 points higher on the sexual function portion of the EPIC-26 HR-QOL. The improvement in sexual function score was statistically significant (p = 0.0226) and more pronounced in long-term follow-up at 18 and 24 months (Figure 2). In addition to the many well-known benefits associated with smoking cessation, lesser-known potential sexual function benefits should serve as additional incentive to quit smoking for men who plan to undergo robotic prostatectomy. The decision to pursue elective surgery opens a window of opportunity during which smokers can finally gather the momentum to quit. After receiving a new prostate cancer diagnosis, patients may be especially amenable to lifestyle changes. Urologists have a unique opportunity to counsel their patients about ways to optimize their overall health before and after surgery.

Current literature points to increasing support for urologists to assume a more prominent role in smoking cessation.27 However, many urologists do not routinely counsel their patients about smoking cessation. A survey of 601 urologists who were treating US patients with bladder cancer reported that approximately 55.6% of urologists had never discussed smoking cessation with their patients.28 Among these respondents, 41% questioned whether smoking cessation would alter the disease course, 10% felt limited by time constraints, and 38% did not believe they were qualified to provide smoking cessation counseling.28 Yet evidence clearly suggests that smoking cessation counseling is both effective and feasible in the urologic setting. Another study prospectively evaluated the efficacy of a urologist’s brief smoking cessation intervention in an outpatient setting.29 These authors reported a 1-year quit rate of 12.1% in the brief smoking cessation intervention group vs 2.6% in the usual-care group.29 Financial reimbursements for smoking cessation counseling can increase urologists’ emphasis on preventative care as well.30

We recognize the limitations associated with our retrospective observational study. However, considering that all baseline demographics and clinicopathology were similar between the 2 cohorts, selection bias was effectively minimized. We acknowledge that the number of smokers in our population was low. Approximately 42.1 million US adults smoke, which corresponds to 17.8% of the population.1 In our study, only 5.5% of cohort patients were identified as smokers. This could be a result of missing data that were not captured by our ancillary staff at the point of care or may be attributable to the underreporting of smoking status in our population. Smoking history was self-reported by patients and not quantified or verified by biochemical means. Also, pack-year history data were not available for our population. It is also possible that patients who quit smoking were motivated to improve their overall health. Thus, they were more likely to exercise, lose weight, and adhere closely to postsurgical penile rehabilitation protocols. These factors may confound the positive effects that we are attributing to smoking cessation. Among those who quit smoking, we were unable to capture the data regarding the specific smoking cessation resources that were used by each patient such as wellness coaches, classes, and pharmacotherapy. Regarding postsurgical penile rehabilitation, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors and vacuum erection devices were offered at the discretion of individual surgeons, so penile rehabilitation was not standardized for our population and we did not capture data regarding patients who used each modality. We also did not adjust for the surgeons’ individual data, in particular to their particular training and skills, nor adjust for the different surgical centers. However, because of the equal experience of our high-volume surgeons, this bias was minimized. We also acknowledge that surgeon-specific outcome variations data (ie, procedure times, ED rates, incontinence rates, etc) were not captured. Lastly, our study’s small sample size may not represent other populations.

Limitations notwithstanding, this study demonstrates the importance of patient smoking cessation counseling before robotic prostatectomy. Smoking cessation is associated with a significant improvement in long-term sexual functional outcomes when other factors are adjusted. Future studies with larger cohorts in a prospective, randomized trial are needed to expand upon our results.

CONCLUSION

Perioperative smoking cessation is a modifiable factor that may be associated with improvement in long-term sexual function following robotic prostatectomy. Findings from our study may elucidate the importance of enrolling men who undergo prostatectomy in a tobacco cessation program for the preservation of their sexual function.

Optimal Function

The highest quality of life attainable for any normal person is the achievement of optimal function, resulting in using all of the assets that each person has.

— Frederick James Kottke, 1917–2014, professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Minnesota, editor of the Krusen Handbook of Physician Medicine and Rehabilitation

Acknowledgment

Brenda Moss Feinberg, ELS, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, King BA, Kenemer JB, Neff L. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014 Nov 28;63(47):1108–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills E, Eyawo O, Lockhart I, Kelly S, Wu P, Ebbert JO. Smoking cessation reduces postoperative complications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2011 Feb;124(2):144–54. e8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.09.013. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorey G. Is smoking a cause of erectile dysfunction? A literature review. Br J Nurs. 2001 Apr;10(7):12–25. 455–65. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2001.10.7.5331. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2001.10.7.5331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman HA, Johannes CB, Derby CA, et al. Erectile dysfunction and coronary risk factors: Prospective results from the Massachusetts male aging study. Prev Med. 2000 Apr;30(4):328–38. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0643. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2000.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He J, Reynolds K, Chen J, et al. Cigarette smoking and erectile dysfunction among Chinese men without clinical vascular disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2007 Oct 1;166(7):803–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm154. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam TH, Abdullah AS, Ho LM, Yip AW, Fan S. Smoking and sexual dysfunction in Chinese males: Findings from men’s health survey. Int J Impot Res. 2006 Jul-Aug;18(4):364–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901436. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijir.3901436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mannino DM, Klevens RM, Flanders WD. Cigarette smoking: An independent risk factor for impotence? Am J Epidemiol. 1994 Dec 1;140(11):1003–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117189. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tengs TO, Osgood ND. The link between smoking and impotence: Two decades of evidence. Prev Med. 2001 Jun;32(6):447–52. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0830. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2001.0830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guay AT, Perez JB, Heatley GJ. Cessation of smoking rapidly decreases erectile dysfunction. Endocr Pract. 1998 Jan-Feb;4(1):23–6. doi: 10.4158/EP.4.1.23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4158/ep.4.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harte CB, Meston CM. Association between smoking cessation and sexual health in men. BJU Int. 2012 Mar;109(6):888–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10503.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410x.2011.10503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McVary KT, Carrier S, Wessells H Subcommittee on Smoking and Erectile Dysfunction Socioeconomic Committee, Sexual Medicine Society of North America. Smoking and erectile dysfunction: Evidence based analysis. J Urol. 2001 Nov;166(5):1624–32. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00005392-200111000-00004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan LK, Withey S, Butler PE. Smoking and wound healing problems in reduction mammaplasty: Is the introduction of urine nicotine testing justified? Ann Plast Surg. 2006 Feb;56(2):111–5. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000197635.26473.a2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sap.0000197635.26473.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuri M, Nakagawa M, Tanaka H, Hasuo S, Kishi Y. Determination of the duration of preoperative smoking cessation to improve wound healing after head and neck surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005 May;102(5):892–96. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200505000-00005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindström D, Sadr Azodi O, Wladis A, et al. Effects of a perioperative smoking cessation intervention on postoperative complications: A randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2008 Nov;248(5):739–45. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181889d0d. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0b013e3181889d0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Møller AM, Villebro N, Pedersen T, Tønnesen H. Effect of preoperative smoking intervention on postoperative complications: A randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2002 Jan 12;359(9301):114–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07369-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bannowsky A, Schulze H, van der Horst C, Hautmann S, Jünemann KP. Recovery of erectile function after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: Improvement with nightly low-dose sildenafil. BJU Int. 2008 May;101(10):1279–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07515.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000 Dec 20;56(6):899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krueger JK, Rohrich RJ. Clearing the smoke: The scientific rationale for tobacco abstention with plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001 Sep 15;108(4):1063–73. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200109150-00042. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200109150-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turan A, Mascha EJ, Roberman D, et al. Smoking and perioperative outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2011 Apr;114(4):837–46. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318210f560. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e318210f560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gades NM, Nehra A, Jacobson DJ, et al. Association between smoking and erectile dysfunction: A population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005 Feb 15;161(4):346–51. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi052. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bacon CG, Mittleman MA, Kawachi I, Giovannucci E, Glasser DB, Rimm EB. A prospective study of risk factors for erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2006 Jul;176(1):217–22. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00589-1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sighinolfi MC, Mofferdin A, De Stefani S, Micali S, Cicero AF, Bianchi G. Immediate improvement in penile hemodynamics after cessation of smoking: Previous results. Urology. 2007 Jan;69(1):163–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.09.026. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catalona WJ, Carvalhal GF, Mager DE, Smith DS. Potency, continence and complication rates in 1,870 consecutive radical retropubic prostatectomies. J Urol. 1999 Aug;162(2):433–8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68578-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidson PJ, van den Ouden D, Schroeder FH. Radical prostatectomy: Prospective assessment of mortality and morbidity. Eur Urol. 1996;29(2):168–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kundu SD, Roehl KA, Eggener SE, Antenor JA, Han M, Catalona WJ. Potency, continence and complications in 3,477 consecutive radical retropubic prostatectomies. J Urol. 2004 Dec;172(6 Pt 1):2227–31. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000145222.94455.73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000145222.94455.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, et al. 5-year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: Results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Urol. 2005 May;173(5):1701–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154637.38262.3a. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson RA, Sadeghi-Nejad H. Tobacco abuse and the urologist: Time for a more proactive role. Urology. 2011 Dec;78(6):1219–23. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.028. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjurlin MA, Goble SM, Hollowell CM. Smoking cessation assistance for patients with bladder cancer: A national survey of American urologists. J Urol. 2010 Nov;184(5):1901–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.140. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bjurlin MA, Cohn MR, Kim DY, et al. Brief smoking cessation intervention: A prospective trial in the urology setting. J Urol. 2013 May;189(5):1843–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.075. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Professional Assisted Cessation Therapy. Reimbursement for smoking cessation therapy: A healthcare practitioner’s guide. Hackensack, NJ: PACT; 2002. [Google Scholar]