Abstract

Medication errors continue to be a concern of health care providers and the public, in particular how to prevent harm from medication mistakes. Many health care workers are afraid to report errors for fear of retribution including the loss of professional licensure and even imprisonment. Most health care workers are silent, instead of admitting their mistake and discussing it openly with peers. This can result in further patient harm if the system causing the mistake is not identified and fixed; thus self-denial may have a negative impact on patient care outcomes. As a result, pharmacy leaders, in collaboration with others, must put systems in place that serve to prevent medication errors while promoting a “Just Culture” way of managing performance and outcomes. This culture must exist across disciplines and departments. Pharmacy leaders need to understand how to classify behaviors associated with errors, set realistic expectations, instill values for staff, and promote accountability within the workplace. This article reviews the concept of Just Culture and provides ways that pharmacy directors can use this concept to manage the degree of error in patient-centered pharmacy services.

A substantial body of evidence from international literature points to the potential risks to patient safety posed by medication errors and the resulting adverse drug events. In the United States, medication errors are estimated to harm at least 1.5 million patients per year, with about 400,000 preventable adverse events.1 In Australian hospitals, about 1% of all patients suffer an adverse event as a result of a medication error.2 Of 1,000 consecutive claims reported to the Medical Protection Society in the UK from July 1, 1996, 193 were associated with prescribing medications.3 Medication errors are also costly to health care systems, patients and their families, and clinicians.4,5 Preventing medication errors has therefore become a high priority worldwide.

A fundamental problem inhibiting the reporting of errors is the variation in how errors are defined, what information is reported, and who is required to report. In the 1970s, a physician's prescription for a dose of a medication not appropriate for a patient's renal function was not considered a medication error. Only after the safety movements of the 1990s were these prescribing errors, attributed mostly to physicians, recognized as medication errors. Near misses are often not reported. Health care workers who believe that an error or near miss is unimportant or causes no harm might decide not to report it. Medication error reports are often difficult to complete and take around 15 to 20 minutes. A busy clinician may not take the time to fill in error details, some of which may not be readily retrievable. In addition, the lack of standardization in the information reported makes it difficult to identify trends in the data.

Many errors go unreported by health care workers; reporting of medication errors in large academic medical centers averages 100 per month (Joseph Melucci, personal communication, February 22, 2017). Given the numbers of doses dispensed by most hospital pharmacies, this reporting percentage is quite low. Only serious or harmful medication errors are reported; errors that do not cause harm but necessitate a systems fix to prevent them in the future are not reported. The major reason errors are not reported is that self-reporting will result in repercussions.6 Health care workers may suffer worry, guilt, anxiety, self-doubt, blame, and depression following serious errors, both for themselves (for disciplinary actions) and for the patient who has been harmed. Support for health care workers in these situations often rests with family members, while some hospitals have programs for “second victims” of medication errors.7 Most health care workers hide the pain of their mistake with silence, instead of admitting their mistake and discussing it openly with peers. Hiding errors can result in further patient harm if the mistake is not identified and fixed; thus self-denial may have a negative impact on patient care outcomes.

The ideal safety system has a robust, easy reporting process for errors and a culture that does not assign blame for errors and reporting; transparent discussion is rewarded. This system increases error reports of all types and establishes a continuous cycle of problem identification and process improvement. Communication and collaboration with risk managers, safety officers, and pharmacy leaders are necessary to provide quality care and encourage a culture of safety. In a culture of safety, open communication facilitates reporting and disclosure among stakeholders and is considered the norm. Even some of the most advanced organizations in terms of safety culture continue to struggle with the balance between personal accountability and a no-blame approach to medication errors.

The shift to a blame-free culture occurred in the mid-1990s with the acknowledgement of human fallibility and the idea that no practice is without error. During this time, the focus moved from the individual to the system processes that allow errors to occur. A series of key papers by physician leaders acknowledged that even the most experienced and knowledgeable employee had the capacity to make an error that would result in harm to a patient.8,9 Although a culture that does not place blame was a step in the right direction, it was not without its faults. This model failed to confront individuals who willfully and repeatedly made unsafe behavioral clinical practice choices. Disciplining health care workers for honest mistakes is counterproductive, but the failure to discipline workers who are involved in repetitive errors poses a danger to patients. A blame-free culture holds no one accountable and any conduct can be reported without any consequences. Finding a balance between punishment and blamelessness is the basis for developing a Just Culture.

State Boards of Pharmacy were slow to change their perspective. The following case in Ohio clearly demonstrated a blaming approach to medication errors. A pharmacist was jailed after he was accused of negligence in failing to detect a pharmacy technician's chemotherapy mixing error that resulted in the death of 2 year-old Emily Jerry.10 There was outcry and concern voiced on both sides of this case, and it caused anxiety and fear in pharmacists that limited reporting errors.

With all processes, human factors are often the cause of mistakes. In the Emily Jerry case, human error resulted in serious consequences for all parties involved. Medication errors create other consequences including lost income and wages, loss of trust in the health care system, decrease in morale, and physical and psychological pain. The majority of medication errors do not result from the reckless behavior but from faulty systems and processes. Pharmacy leaders should strive to put systems in place that serve to minimize human error and implement a Just Culture way of thinking both inside and outside of the pharmacy department. To do this, pharmacy leaders must understand how to classify behaviors associated with errors, set realistic expectations, instill values for staff, and promote accountability within the workplace.

This article reviews the concept of a Just Culture of safety and its implications for pharmacy leaders involved in balancing accountability and system failures resulting from medication errors. The specific aims of this paper are to (a) review the various behaviors involved in any error, (b) describe the fundamental leadership approaches in establishing a Just Culture of safety, and (c) describe how the Just Culture algorithm is applied to a medication error. While operational and clinical effectiveness is important in developing patient-centered pharmacy services, promoting and establishing a Just Culture of safety provides a framework for open dialogue and continuous process improvement to ultimately prevent serious and harmful medication errors.

BEHAVIORS CONTRIBUTING TO ERRORS

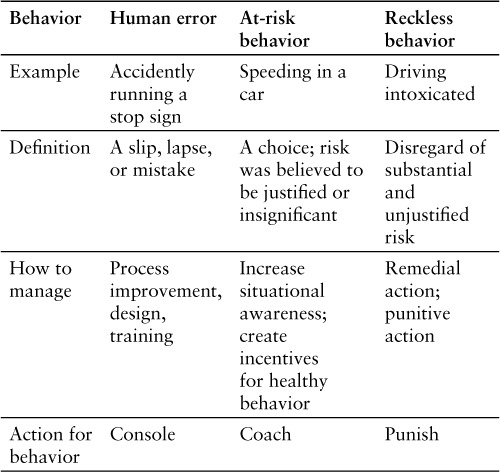

There are 3 types of behavior that contribute to any error: human error, at-risk behavior, and reckless behavior (Table 1). Human error involves unintentional and unpredictable behavior that causes or could have caused an undesirable outcome. Often there are faults within the system that allow the error to occur. Human behavior that results in errors may include incorrect drug dispensing, improper dosing of medications, and monitoring errors. For example, if a prescriber inadvertently chooses a medication for the wrong patient, this may be classified as a human error. It is likely that the prescriber did not mean to choose the incorrect patient, and the error slipped through the cracks. If the pharmacist verifies an incorrect dose for a patient based on renal function, this could be classified as human error in certain circumstances. If a nurse selects the wrong rate from the screen of a patient-controlled analgesia device, this may be a human error due to how the machine is configured or how the screen is presented to the nurse. The typical response to these behaviors is to console the employee and make improvements to the system to prevent further errors.

Table 1.

Behaviors associated with mistakes and errors16

At-risk behavior is when an employee makes the decision to take a risk that he or she feels is insignificant or justified. More often than not, workers drift into unsafe behaviors because of a systems issue. At-risk behavior may be relatively common, depending on how it is defined. Examples of at-risk behavior include dispensing medications without complete knowledge of the medication, overriding computer alerts without consideration, or failing to ask a colleague to double check a high-alert medication.11 The rewards of at-risk behaviors can become so apparent that the perception of the risk is not obvious and therefore the risk seems justified. At-risk behavior is best addressed by coaching and engaging the employee to identify ways for error prevention in the future. Behavior of employees that continue to be at-risk type despite coaching can then be categorized as reckless.

Employees who make a conscious choice to disregard substantial and unjustifiable risk for subjective reasons that do not meet the Occam's razor test (where the simplest explanation of the choice is the appropriate one) are exhibiting reckless behavior. This includes working while intoxicated, tampering with or contaminating equipment or medications prior to operating or administering, encouraging family members to press the dosage button on a patient controlled analgesia device for their relative, and recommending clearly outrageous dosages or medications (eg, 4 g of undiluted cefazolin injected directly into the vein as a prophylactic antibiotic regimen), or deliberately withholding pain medications. Disciplinary actions are almost always employed when reckless behavior is present; in some instances, legal action may be taken if a patient is harmed by an intoxicated or impaired health care professional.

LEADERSHIP APPROACHES IN ESTABLISHING A JUST CULTURE OF SAFETY

Setting Expectations

Just Culture strikes a balance between punishment and blamelessness. It fosters an environment of openness and fairness in order to facilitate the honest reporting of errors. Focusing on the differences between human error, at-risk behavior, and reckless behavior and assigning justice based on the quality of the choice made by the employee are key features of a Just Culture. By designing safe systems that work proactively, a Just Culture is prepared to assess the daily risks inherent in its operations. This leads to maximum reliability and the prevention of future events.

A Just Culture is more concerned with the potential for risk and catching it before harm reaches the patient than with punishing individuals based on an outcome that may be the result of human error alone. Expectations should be set for handling errors so that employees know what to expect if or when they make an error. Each time an error occurs, a consistent review process of behavior and action should be used. Many federal, state, and professional organizations have set expectations for Just Culture in their health care systems. These include the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Illinois Nurses Association, the American Nurses Association, and the Anesthesia Patient Safety Society. Effective organizations recognize that an optimal system design provides the framework for success, and they also realize that employees have the potential to perform better than the expectations of the system.12

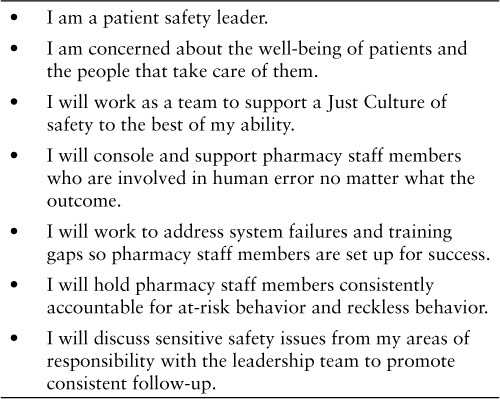

Expectations for staff should be defined at the beginning of their employment by incorporating medication safety and the explanation of a Just Culture into the onboarding process. From the start, employees should understand the importance of medication safety and the valuable role they play in the process of keeping patients safe. All pharmacy employees should meet the medication safety pharmacist during their on-boarding period in case they are involved in an error in the future. In addition, it is recommended that departments adopt a Just Culture pledge that focuses on the essentials of this culture and commits staff to report errors in the spirit of properly weighing professional accountability and system failure. An example of a draft of a pledge is shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Draft pledge to uphold a Just Culture of safety

A manager or leader of Just Culture must realize that human error is inevitable and that employees will make mistakes. Human error can be expected. The challenge lies within the at-risk behaviors. Patterns of at-risk behavior can be broken by coaching the employees and giving them the opportunity to improve the behaviors determined to be at risk. If they are not open to this coaching or do not respond to this method of remediation, then the expectation that their behavior will change comes into question.

Values Clarification

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) argues that patient safety should not be a priority in health care, but should be integrated into each work process.13,14 Although this may come as a surprise, ISMP feels that when patient safety is labeled as a priority for the institution, it falls on a long list of other important activities that also have priority. Patient safety should be an essential part of every process – and not a priority to be reshuffled. It is human nature to shift priorities, sometimes on a daily basis, based on varying circumstances and competing concerns. Patient safety should always be the center of attention for everyone in the health care system. Patient safety should be a value associated with every health care priority, linked to every activity, and never compromised regardless of the circumstances.

If all employees consistently follow safe procedures and uphold a best practice in every aspect of their job, working safely will eventually become incorporated into their value system. This is much easier said than done, because it is often much easier and rewarding to take risks than to work safely. Human behavior contradicts patient safety efforts, because the rewards for risk taking are immediate and positive and the punishment for risk taking is remote and very unlikely. Patient safety must remain a sustained value, and safe behavior must be encouraged throughout the institution.

For a Just Culture to be sustained within an organization, there must be a strong commitment to the core values of the institution. There must also be support from human resources departments and executive leadership. Many leaders utilize academic models that may oversimplify human behavior and place a focus on procedural compliance or labeling behaviors as unsafe acts only after an adverse outcome occurs. A Just Culture takes a proactive approach and starts with the question, “Why do our organizations exist and to what end or purpose do they exist?” Identifying these values helps to guide expectations and achieve a balance between punitive actions and a blame-free environment when it comes to at-risk behaviors.

Incorporating employees into the formation of these values is vital. Giving front-line employees the opportunity to contribute to the creation of patient safety values increases their investment in a Just Culture. Identifying common themes during the creation of these values and formulating them into a Just Culture pledge for each employee to sign is a way to ensure the core values of the organization are upheld. Once these values are established and the pledge is signed, this should become part of each employee's everyday vocabulary in the institution. Leaders should make constant references to the values of the organization and be transparent about how employees uphold or fail to uphold these values on a daily basis. Everyone should be aware of the core values of the institution and feel comfortable discussing them in a positive manner while learning what can be done to better match practice with values.

Forcing Accountability

To encourage a Just Culture, organizations must support a robust accountability model.15 An organization must have valid and transparent measures, knowledge of how often harms are prevented, and interventions or incentives to improve performance. Accountability also requires an understanding of system design, human behavior, and how to achieve maximum reliability within each. System design and human behavior are symbiotic, which means that the relationship between these 2 factors can be mutually supportive or can contradict one another. The systems designed to address the potential for human error depend on how often the error occurs and how serious the consequences are. On the other hand, the choices people make depend on how the systems operate. Health care organizations must be accountable for both system failures and human errors and engineer effective controls such as barriers, redundancies, and recovery strategies to achieve good outcomes.

A Just Culture promotes a values-supportive model of shared accountability. This culture holds organizations accountable for the systems they design and for how they respond to staff behaviors in a fair and just manner. This balanced accountability helps to manage the complicated risks inherent in health care. Shared accountability further requires the opinions of employees from all disciplines to be incorporated in an improved system. By actively involving employees in this process, they are encouraged to be more accountable for their actions and to feel a heightened sense of responsibility when problems arise.

This shared accountability also applies to the transparency of patient safety data. If organizations want their employees to be integrated into system improvement efforts, they must also be comfortable sharing data about the current faults in the system. Regular reporting of error trends and system failures should be communicated to all staff. A Just Culture is one that will empower its employees to promote patient safety, and it must also provide them with the tools to do this effectively.

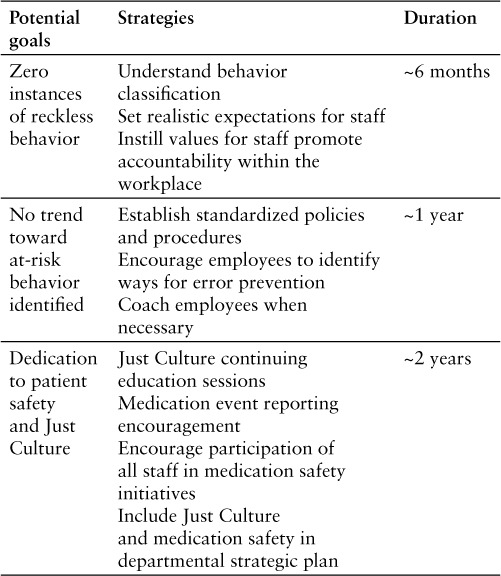

Once expectations for employees are defined and organizations have instilled the Just Culture concept into the core values of everyday practice, individuals must be held accountable. Incorporating a Just Culture adherence metric into annual evaluations for individual employees is one way to standardize accountability (Table 3). Listing key results related to Just Culture and medication safety are guaranteed ways to hold employees accountable.

Table 3.

Potential employee evaluation goals

Assigning these goals to all employees ensures that patient safety is valued and enables organizations to identify trends in behavior. Although it is important to track individuals who perform recklessly, it is also important to reward those employees who continuously report good catches or are outstanding patient safety stewards. Incentivizing and rewarding those who are excellent supporters of Just Culture on a daily basis is crucial to holding all employees accountable and promoting a positive culture. The overarching goal of accountability is to create a continuously learning organization and instill a sense of accountability within all employees. Being a good steward of accountability demonstrates responsibility to the patients and promotes a Just Culture of safety throughout the organization.

CASE EXAMPLES OF APPLYING JUST CULTURE OF PATIENT SAFETY

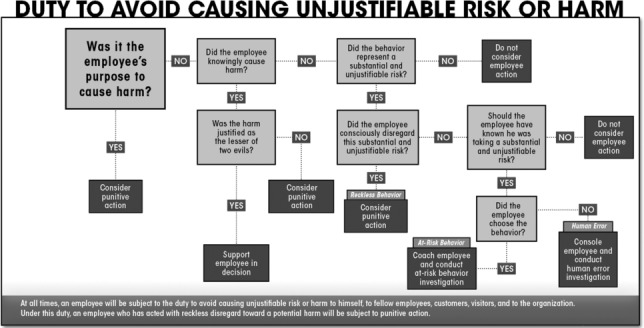

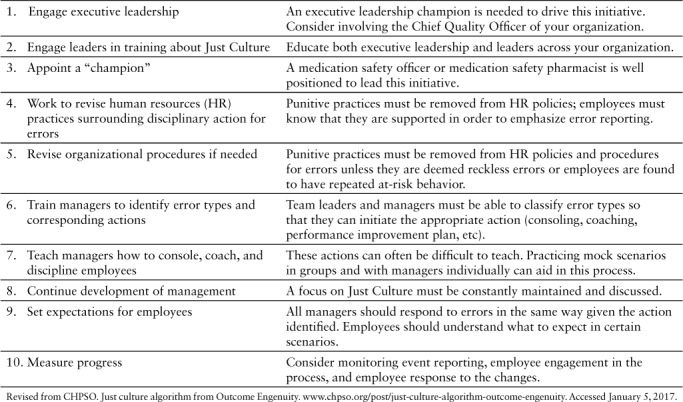

A framework originally created by Outcome Engenuity can be applied to implementing Just Culture in your organization (Figure 1).16 Ten steps are recommended for making Just Culture “real” in an individual organization (Table 4). Shifting to a Just Culture model is a shared responsibility and requires a commitment by everyone involved to eliminate the possibility of error. Management should help staff learn how to prioritize their work and clearly define primary goals (patient safety) from secondary goals (productivity, efficiency), create an open learning environment, and lead by example. To do this, training for how to effectively console, coach, and discipline employees is essential. Additionally, leaders should ensure that the medication safety team is prepared for the increased workload that will result from increased event reporting. Behavioral choices of staff should be continuously monitored, and employees should understand that patient safety is a primary value in their pharmacy, feel enabled to report errors, and feel supported by the team.

Figure 1.

Just Culture algorithm.16 Reprinted with permission from Outcome Engenuity.

Table 4.

Ten-step approach for implementing a Just Culture16

A few case examples are listed that review how the algorithm is used in evaluating the approach to a specific medication error. These cases are not based on actual patients, but they represent the types of errors that occur in a health system. In applying this algorithm, details of the error should be reviewed with a group (administrators, quality improvement team, and clinical care team). When discussing the error, it is important to think of how a reasonable pharmacist would act in that situation and what thought process, judgment, and decisions would seem reasonable given the predicaments of this situation.

Case 1

Situation. A pharmacist verifies a medication order for vancomycin 1,500 mg for a patient admitted to the intensive care unit from the emergency department. Verification included checking the order against appropriate laboratory values, patient weight, and indication. The pharmacist failed to check the emergency department medication record, where a dose of 1,500 mg of vancomycin had been administered. The pharmacist verifies, prepares, and dispenses the 1,500 mg vancomycin dose, with the nurse administering the dose. Several days later, the patient's serum creatinine begins to rise and a diagnosis of acute kidney injury secondary to vancomycin is made with prolonged hospital stay and interventions (eg, dialysis). This mistaken repeat of the vancomycin dose resulting from the pharmacists' failure to check the emergency department medication administration record was determined to be the root cause of the error. The pharmacist is a long-standing employee who is well respected by physicians and is seen as a role model for ICU pharmacy care.

Application of the Just Culture algorithm: The pharmacist did not intend the act, and there was no suspicion of substance abuse or medical condition. The pharmacist did depart from generally accepted performance expectations, as it is a policy to review all medication administration records prior to dispensing a medication to check for duplicate therapy issues. This activity did not pose unacceptable risk or poor performance; others would not act the same under similar circumstances. There were no deficiencies in training, and the pharmacist chose the behavior. Therefore this error would be classified as at-risk behavior resulting in coaching the individual.

Case 2

Situation: The evening pharmacist was behind in the verification queue for the shift, because other staff members were ill or attending a Code Blue response; there was a full patient census. The evening pharmacist has the reputation for verifying the highest numbers of orders during a shift; on a recent shift, the pharmacist verified over 400 individual orders, which is far beyond (>2 SD) other pharmacists. This pharmacist has been counseled about a past history of medication errors; many of them were careless as their root cause was the bypass of accepted safeguards in the department for order review and verification. During the shift report, the evening pharmacist reported to the night pharmacist that they did not review laboratory values for most of the orders verified where this action was required. To quote the evening pharmacist during report, “I was too busy and wanted to get out on time – so I blew it off – no biggie.” The following day, the director of pharmacy received 2 complaints from physicians who reported that drug levels were not optimal and should have been adjusted based on laboratory values but were not because of the evening pharmacists' negligence.

Application of the Just Culture algorithm (Figure 1): The evening pharmacist did intend the act, but no patient harm resulted. There are no suspicions of health issues or substance abuse, and the pharmacist has no known medical conditions or substance abuse issues; however, the behavior did represent a substantial and unjustifiable risk. The pharmacist consciously disregarded the unjustifiable risk in this scenario. This error would be classified as reckless/negligent behavior and would warrant disciplinary action. In this case, it is most likely that serious progressive discipline would be required, including suspension, retraining, and some sort of mentoring program.

These cases demonstrate how to use the algorithm to determine a suggested course of action in coaching or providing feedback to staff on errors. This algorithm also helps organizations further understand errors and their root causes by clearly identifying events contributing to the errors. We highly recommend using this algorithm in evaluating medication errors.

CONCLUSION

A Just Culture identifies 3 types of behavioral choices: human error, at-risk behavior, and reckless behavior. It establishes a fair and transparent process for evaluating errors and determining a course of action based on the quality of the behavior and not on the outcome of the error. Just Culture is a model of shared accountability where both management and staff are held accountable. This model can be integrated into any health care setting by classifying behaviors associated with errors and providing consistent follow-up with employees. Setting realistic expectations, instilling safety values, and promoting accountability within the workplace will help to promote a Just Culture as an organization strives to develop patient-centered pharmacy services. By using an algorithm as a guide, the pharmacy leader can begin to develop a culture that balances accountability and systems failures and promotes error-free and patient-centered pharmacy services.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aspden P, Institute of Medicine. . Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors. Preventing Medication Errors. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Runciman W, Roughhead E, Semple S, Adams R.. Adverse drug events and medication errors in Australia. Int J Qual Healthcare. 2003; 15( suppl): i49– 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chief Pharmaceutical Officer. . Building a Safer NHS for Patients. Improving Medication Safety. London: Department of Health; 2004. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4. http://Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicy-AndGuidance/DH_4071443. Accessed February 11, 2017.

- 5. Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, . et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1997; 277: 307– 311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weissman JS, Annas CL, Epstein AM, . et al. Error reporting and disclosure systems: Views from hospital leaders. JAMA. 2005; 293: 1359– 1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu AW. Medical error: The second victim: The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ. 2000; 320: 726– 727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. . Our long journey towards a safety-minded just culture. Part I: Where we've been. ISMP Medication Safety Alert. September 7, 2006. Accessed December 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. . Our long journey towards a safety-minded just culture. Part II: Where we're going. ISMP Medication Safety Alert. September 21, 2006. Accessed December 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Emily's story. The Emily Jerry Foundation. https://emilyjerryfoundation.org/pages/emilys-story/. Accessed February 11, 2017.

- 11. Griffith KS. The Growth of a Just Culture. Jt Comm Perspect Patient Safety. 2009; 9: 8– 9. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Griffith KS. Error prevention in a Just Culture: System design or human behavior? Jt Comm Perspect Patient Safety. 2010; 10( 6): 10– 11. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. . Patient safety should not be a priority in healthcare. Part I: Why we engage in “at-risk behaviors.” ISMP Medication Safety Alert. September 23, 2004. Accessed December 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. . Patient safety should not be a priority in healthcare. Part II: Reducing “atrisk behaviors.” ISMP Medication Safety Alert. October 7, 2004. Accessed December 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pronovost PJ. Learning accountability for patient outcomes. JAMA. 2010; 304( 2): 204– 205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. CHPSO. . Just culture algorithm from Outcome Engenuity. www.chpso.org/post/just-culture-algorithm-outcome-engenuity. Accessed January 5, 2017.