Abstract

Background:

The only treatment for celiac disease (CD) is a gluten-free diet (GFD). However, there is interest among patients in a medical therapy to replace or help with a GFD. Therapies include gluten-degrading enzymes (glutenases). There are glutenases available marketed as dietary supplements that have not been demonstrated to digest the toxic epitopes of gluten.

Methods:

We investigated the contents, claims, and disclaimers of glutenase products and assessed patient interest using Google AdWords to obtain Google search frequencies.

Results:

Among 14 glutenase product, all contained proteases, eight contained X-prolyl exopeptidase dipeptidyl peptidase IV, two did not state the protease contents, and eight failed to specify the name or origin of all proteases. Eleven contained carbohydrases and lipases and three probiotics. One declared wheat and milk as allergens, two contained herbal products (type not stated) and one Carica papaya. Thirteen claimed to degrade immunogenic gluten fragments, four claimed to help alleviate gastrointestinal symptoms associated with eating gluten. Disclaimers included not being evaluated by the US Food and Drug Administration and products not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. On Google AdWords, the search frequency for the product names and the search terms was 3173 searches per month.

Conclusions:

The names of these products make implicit claims that appear to be supported by the claims on the labels and websites for which there is no scientific basis. Google search data suggest great interest and therefore possible use by patients with CD. There needs to be greater oversight of these ‘drugs’.

Keywords: celiac disease, glutenases, gluten free diet

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is an autoimmune disorder affecting approximately 1% of the American population. It is characterized by an inflammatory immune reaction in the small intestine triggered by consumption of gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye. The autoimmune reaction causes flattening of the villi in the small bowel, leading to malnutrition, anemia, osteoporosis, infertility, growth problems in children, and other disorders. While the clinical manifestations vary greatly, acute exposure to gluten in CD may cause vomiting, diarrhea, and bloating. Currently, the only available treatment for CD is complete elimination of gluten-containing foods from the diet.1

Gluten’s markedly high proline content causes a complex structure with regions which are largely inaccessible to human endoproteases, allowing large, proline-rich gluten fragments to reach the small intestine intact.2 These large molecules, the products of gluten digestion, are up to 33 amino acid in length remain. These molecules include the 33-mer α-gliadin and the 26-mer γ-gliadin fragments. These particularly toxic molecules enter the small intestinal lamina propria, become activated by the enzyme tissue transglutaminase that facilitates their binding to HLA-DQ2 and -DQ8 on antigen-presenting T cells. Binding is optimized with fragments nine or more amino acids in length. Therefore, reduction of the immunogenicity of gluten requires that it be degraded into fragments shorter than nine amino acids before the protein reaches the small intestine.3 One therapeutic approach is to administer prolyl endopeptidases that can completely degrade gluten in the stomach, minimizing the presence of the larger toxic gluten fragments. A few enzymes have been proposed for this purpose.

Prolyl oligopeptidases from the organisms Flavobacterium meningosepticum, Sphingomonas capsulate, and Myxococcus xanthus have shown promise, being able to successfully degrade immunogenic gluten amino acid sequences, but they are optimally active outside gastric pH levels and are degraded by pepsin,4 rendering these proteases useless in a gastric environment. A combination of aspergillopepsin from Aspergillus niger and dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV), an X-Pro N-terminal protease from Aspergillus oryzae, was found to successfully degrade small amounts of gluten in vitro.5 ALV003, produced by Alvine Pharmaceuticals (San Carlos, CA), is a combination of a cysteine protease from barley and a prolyl endopeptidase from Sphingomonas capsulata that has been shown to successfully degrade immunogenic gluten fragments in the stomach,6,7 and a synthetic enzyme called KumaMax from the Institute for Protein Design at University of Washington (Seattle, WA, USA) had similar in vitro results to ALV003,8 but is still under development. Finally, Tolerase G, a commercially available dietary supplement sold by DSM (Kaiseraugst, Switzerland) that contains Aspergillus niger derived prolyl endoprotease (AN-PEP), has had very promising in vitro, ex vivo, and in vitro initial results.8,9

In addition to these gluten-degrading enzymes (glutenases), there are numerous dietary supplements already on the market that are marketed to aid in the digestion of gluten and reduce its toxicity. These products are mainly based on DPP-IV, which has limited proteolytic activity on its own. They are most prominently marketed to patients with CD or gluten intolerance who are maintaining a gluten-free diet (GFD) by choice. In this study, we investigate various aspects of 14 commercially available glutenase products. We show that these products have minimal published evidence of efficacy and may actually be hazardous to patients with CD who are taking them.

Methods

Identifying glutenase products

We conducted a Google search for glutenases using the following terms and variations thereof: ‘glutenase’, ‘gluten enzyme’, ‘digest gluten’, and ‘celiac enzyme’. We used online articles to supplement our search to ultimately find 14 products. Our criteria for glutenase products required that they be commercially available, enzyme supplements, claim to degrade gluten, and available in the United States.

Collecting product data

We examined the manufacturers’ websites, product labels, and other published information and advertising materials for the glutenase products to find the following data: active ingredients; declared allergen content; indications for use; data supporting efficacy; claims made about the product; disclaimers; and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classification of the product (i.e. food item, dietary supplement, drug, etc.).

Google search frequency

We used Google AdWords’ Keyword Planner tool to obtain Google search frequency data. We looked at search frequency for the glutenase product names as well as a few related search terms (‘CD’, ‘gluten free’, and the search terms we used to find the products) for basis of comparison. For these search terms, we used Google’s data for the latest available six months’ preceding data collection (January 2015–June 2015) to ensure current data; we limited the inquiry to the United States for the purpose of keeping the data local; and we used the data separated by month rather than the monthly average presented by the Google AdWords tool to minimize rounding error apparently inherent to Google’s calculations.

Results

Active ingredients

Through our Google search, we found 14 glutenase products that met our criteria (Table 1). All of the products were classified as dietary supplements and, as such, are exempt from many FDA labeling standards. We first identified the active ingredients of each of the products from their content labels (Table 2). We found that all of the products contained proteases, while 8 of the 14 products contained the X-prolyl exopeptidase DPP-IV, and one, Digest Gluten Plus, listed ‘gluten specific bacterial protease’ content. None of the products listed aspergillopepsin content. Two of the products, BioCore DPP IV and SerenAid, did not clearly enumerate the protease contents, and eight of the products (BioCore DPP IV, Digest Gluten Plus, Gluten-Ade, Gluten Digest, Gluten Enzyme DG, Gluten-Zyme, Glutenaid, and SerenAid) failed to specify what one or more of the contained proteases were.

Table 1.

Glutenase product names and manufacturers.

| Product name | Manufacturer |

|---|---|

| BioCore DPP IV | Swanson Health Products (Fargo, ND) |

| Digest Gluten Plus | Seroyal (Pittsburgh, PA) |

| Gluten-Ade | Fain’s Herbacy (Eurkea Springs, AK) |

| Gluten Cutter | Healthy Digestives (West Palm Beach, FL) |

| Gluten Defense | Enzymatic Therapy (Green Bay, WI) |

| Gluten Digest | NOW Foods (Bloomingdale, IL) |

| Gluten Enzyme DG | Vitacost (Boca Raton, FL) |

| Gluten-Zyme | Country Life (Hauppauge, NY) |

| Glutenaid | CVS (Woonsocket, RI) |

| GlutenEase | Enzymedica (Venice, FL) |

| ProCellax DG2 | Genufood Energy Enzymes Corp. (Los Angeles, CA) |

| SerenAid | Klaire Laboratories (Reno, NV) |

| Similase GFCF | Integrative Therapeutics (Green Bay, WI) |

| ZGlutn | Systemic Formulas (Ogden, UT) |

Table 2.

Enzyme, probiotic, and declared allergen content of glutenase products.

| Product name | Proteases | Carbohydrases | Lipases | Probiotics | Declared Allergens |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioCore DPP IV | #* | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Digest Gluten Plus | 4 | 0 | 0 | – | Wheat, milk |

| Gluten-Ade | 4 | 3 | 0 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | – |

| Gluten Cutter | 1 | 9 | 1 | – | – |

| Gluten Defense | 1 | 4 | 1 | – | – |

| Gluten Digest | 4* | 2 | 0 | – | – |

| Gluten Enzyme DG | 3* | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Gluten-Zyme | 1 | 2 | 0 | Lactobacillus spp., Lactobacillus lactis, Brevabacillus brevis, Bifidobacterium lactis | – |

| Glutenaid | 2 | 1 | 0 | – | – |

| GlutenEase | 2* | 2 | 0 | – | – |

| ProCellax DG2 | 2* | 7 | 1 | – | – |

| SerenAid | #* | 1 | 0 | – | – |

| Similase GFCF | 1† | 4 | 1 | – | – |

| ZGlutn | 1† | 7 | 1 | Bacillus coagulans | – |

Numbers indicate number of unique enzymes listed in the category. # indicates no specific number of enzymes listed; – indicates no applicable data for the field.

Product claims dipeptidyl peptidase IV content or activity.

Eleven of the 14 glutenase products contained other enzymes, including carbohydrases; Gluten Cutter had the highest number of carbohydrases at nine. Five of the products contained lipases, though no product listed more than one lipase, nor did any product containing lipases specify what lipase it contained, nor their sources. Neither carbohydrases nor lipases degrade gluten proteins.

Three of the products contained probiotics, with Lactobacillus species occurring in two products. No other bacterial family was listed as a probiotic in more than one product.

The FDA requires that dietary supplements declare any ‘major allergens’ (including wheat) that may be present in the products. One of the glutenase products (Digest Gluten Plus) declared wheat content, as well as milk. As seen in Table 3, three of the products possibly contained plant matter, two contained herbal products (type not stated) and one Carica papaya (a tropical fruit).

Table 3.

Origins of active ingredients in glutenase products.

| Product name | Fungi |

Bacteria |

Plants |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus spp. | Other | Bacillus spp. | Herbs | Other | |

| BioCore DPP IV | oryzae, melleus | – | – | – | – |

| Digest Gluten Plus | Oryzae | – | subtilis | – | – |

| Gluten-Ade | oryzae, niger | trichoderma reesei | subtilis | – | Carica papaya |

| Gluten Cutter* | – | – | – | 3 | – |

| Gluten Defense* | – | – | – | – | – |

| Gluten Digest | oryzae, niger, melleus | – | – | – | – |

| Gluten Enzyme DG | oryzae, melleus | – | – | – | – |

| Gluten-Zyme | oryzae, niger | – | – | – | – |

| Glutenaid | oryzae, niger | – | – | – | – |

| GlutenEase* | – | – | – | – | – |

| ProCellax DG2* | – | – | – | – | – |

| SerenAid* | – | – | – | – | – |

| Similase GFCF | oryzae, niger, melleus | Saccharomyces spp. | – | – | – |

| ZGlutn* | – | – | – | 7 | – |

Data exclude bacteria used as probiotic. – indicates no applicable data for the field.

Product label does not list origins of all active ingredients.

Ingredient origins

After the active ingredients, we looked at the origins of the active ingredients of the glutenase products (Table 3). Eight of the products used fungal sources; each of these eight used Aspergillus oryzae, five used Aspergillus niger, four used Aspergillus melleus, and two used non-Aspergillus species alongside Aspergillus species. Two products (Digest Gluten Plus and Gluten-Ade) used bacterial sources, excluding bacteria used as probiotics; both of these products used Bacillus subtilis. Three products used plant sources, two of which used the plants as herbs, while the third used a papaya-derived protease. Unfortunately, we are not aware of where all of the ingredients come from, as the manufacturers do not list all of the origins, as is noted in Table 3.

Claims and disclaimers

We then identified the claims and disclaimers the manufacturers made on the products (Table 4). Thirteen of the 14 products claimed to degrade immunogenic gluten fragments, as is the stated intent of the products; the one product that did not make this claim actually made no claims whatsoever. Four products claimed to help alleviate gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms associated with eating gluten. Six products made claims regarding their activity in a ‘range of pH’ found in the stomach. No other claims relevant to CD were made by any of the products.

Table 4.

Manufacturer claims and disclaimers on glutenase products.

| Product name | Types of claims | Disclaimers | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioCore DPP IV | A | C | E | F | ||||||||

| Digest Gluten Plus | A | F | G | |||||||||

| Gluten-Ade | – | D | ||||||||||

| Gluten Cutter | A | B | D | H | ||||||||

| Gluten Defense | A | D | E | F | ||||||||

| Gluten Digest | A | C | H | |||||||||

| Gluten Enzyme DG | A | D | E | F | ||||||||

| Gluten-Zyme | A | D | E | F | G | I | ||||||

| Glutenaid | A | B | D | E | J | |||||||

| GlutenEase | A | C | D | E | ||||||||

| ProCellax DG2 | A | B | C | D | ||||||||

| SerenAid | A | C | D | |||||||||

| Similase GFCF | A | C | D | |||||||||

| ZGlutn | A | B | D | E | ||||||||

A, product degrades or aids in digestion of harmful gluten peptides; B, alleviates gastrointestinal symptoms associated with gluten consumption and gluten intolerance; C, these enzymes remain active in a ‘wide range’ of pH or in gastric conditions; D, these statements have not been evaluated by the US Food and Drug Administration; this product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease; E, this product is not intended to replace a gluten-free diet for individuals with celiac disease (CD); F, if you are pregnant or breastfeeding, consult your healthcare practitioner prior to use; G, discontinue use if any adverse reactions occur; H, if you have CD, use only under your practitioner’s supervision; I, discuss use with your physician; J, consult a physician if symptoms of gluten sensitivity persist. – denotes no applicable statements.

Along with these three types of claims, the manufacturers also included many disclaimers; the individual products carried as many as five disclaimers. The most prevalent disclaimer, present on 11 of the products, was the standard ‘These statements have not been evaluated by the FDA. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.’ Similarly, five products advised that pregnant and breastfeeding patients take extra precautions, and two products advised that patients discontinue use if they react adversely to the product. More notably, however, one product advised patients to discuss using the product with their physicians; one said to contact a physician if gluten sensitivity symptoms persist while using the product; two products advised that patients with CD use the products only under a physician’s supervision; and seven products stated that patients with CD should maintain a GFD even while using the product.

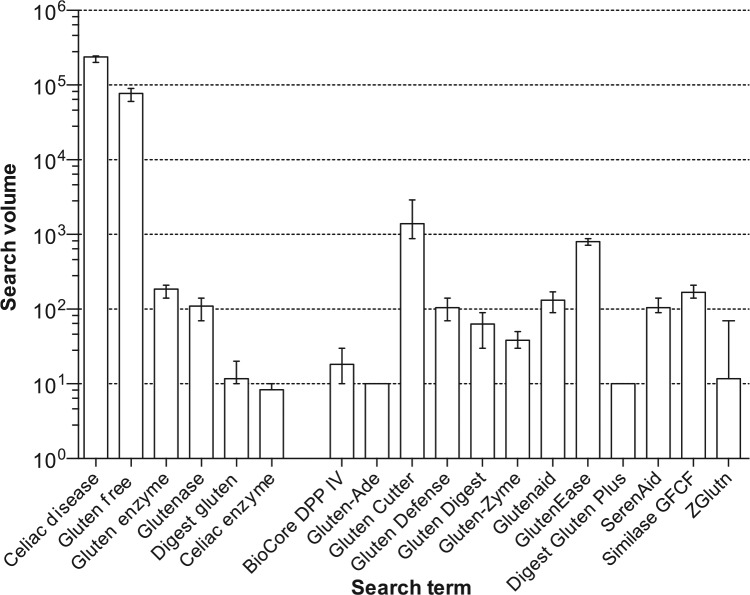

Search frequency

Using Google AdWords to obtain search frequency data, we found that the Google search frequencies for the glutenase products’ names is remarkable (Figure 1). Gluten Cutter had the greatest search volume at an average of 1397 searches per month in the United States, which was only 170 searches less that of ‘CD’ and 55 times lower than that of ‘gluten free’, the only available therapy for CD. Of note, the combined search frequencies for the product names and the search terms we used to find the products was 3173 searches per month, only about 75 times lower than that of ‘CD’ and 24 times lower than that of ‘gluten free’.

Figure 1.

Monthly Google search volume for product names, January 2015–June 2015. Columns represent mean search volume. For comparison searches for CD and gluten free are included as well as the glutenase product names. Monthly search volumes obtained from Google AdWords. There were insufficient data for Gluten Enzyme DG and Procellax DG2.

Discussion

The GFD is currently the only available proven treatment for CD, but it is burdensome and a factor in the quality of life of individuals with CD.10,11 In addition, most with CD consume gluten either intentionally or unintentionally.12 It is understandable that those with CD desire and need alternative therapies to either replace or assist them with the GFD.13,14 This is also evident from our data. People are looking for therapies for CD, given the 3173 searches/month aggregate Google search frequency for the search terms we used to find the glutenase products and the product names themselves, the results comparable to searches for information on ‘CD’. The fact that we found the 14 glutenase products in this study using such search terms as ‘digest gluten’ and ‘celiac enzyme’, among others, demonstrates how patients with CD may be finding these products.

There has been considerable interest in the research and pharmaceutical development of potential therapies for CD.15 A major area of research is the development of enzyme preparations that will digest the toxic fragments of gluten in the stomach preventing exposure of these fragments to the intestinal mucosa.16 The development of specific enzymes that digest the toxic fragments of gluten has advanced considerably to phase II clinical studies.17 However, the glutenases in the commercially available products that we investigated have not been demonstrated to digest the immunogenic, toxic fragments of gluten in the acid milieu of the stomach.3

The glutenase products we investigated almost unanimously assure degradation of gluten to minimize or eliminate the effects of consuming gluten. Many products also claim to diminish various GI symptoms. Even the names make implicit claims: Gluten Cutter, Gluten Defense, GlutenEase, and other similar names hold the clear suggestion of protection against gluten consumption. All of these claims may be very alluring to patients with CD who feel restricted by the diet. There is very little evidence, however, that these products actually do what they claim to do. One paper finds only 64% hydrolysis of gluten by a particular enzyme combination including DPP-IV.18 Another study reports on DPP-IV degradation of the N terminus of gluten peptides but does not specify the speed of degradation or efficacy in gastric conditions.19 In another study, it was specifically found that current commercially available glutenases, primarily DPP-IV-based products, are not effective in degrading the toxic epitopes of gluten; the five products tested by Janssen and colleagues left the immunogenic amino acid sequences in gluten completely intact.3 Indeed, it is entirely possible that any relief patients may experience from the glutenase products we investigated can be attributed to the placebo effect or the carbohydrases and lipases paired with an underlying, undiagnosed digestive condition. Thus, the efficacy claims made by the glutenase product manufacturers are misleading and may cause patients to cause themselves harm by eating gluten while believing they are protected.

Beyond the apparent lack of efficacy of the glutenases, the products in and of themselves may actually pose a hazard to patients. One of the products declared wheat content in the allergen information. This wheat content poses a clear hazard to patients with CD using the product, and it is possible that other products contain undeclared wheat (or other allergens), as the FDA does not closely monitor these enzyme supplements and their labels. Recent publicity in the lay press20 has highlighted the high rate of mislabeling of dietary supplements, lack of the product on the label detected in the product, and high rates of product substitution with nondisclosed items such as wheat, rice, and noxious herbs.21 Previous work done by our group has found that 55% of probiotics contain gluten, despite being labeled gluten free, and 18% contain more than the 20 ppm limit for gluten-free foods set by the FDA,22 creating a potential hazard to patients with CD. Furthermore, the probiotic content and bacterial and fungal origins of the glutenase products we investigated are worrisome. The use of these microorganisms may unintentionally permit pathogenic contamination of the products, in addition to inadvertent gluten exposure.23

The array of disclaimers on the products in this study may be another issue. Eleven of the products actually say that they are ‘not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease’, as part of the standard FDA-mandated disclaimer, which included CD. These products should be clearly labeled with disclaimers about use and risks of use in CD. Furthermore, seven of the products explicitly state that they are not intended to replace GFD in patients with CD, along with other disclaimers which should indicate to these patients that the drugs are not effective in treating CD. Two products even advise patients with CD not to use the product without physician supervision. Unfortunately, Kesselheim and colleagues24 found that such disclaimers, which should really serve as warnings, do not consistently communicate the issues they are trying to express. Instead, these disclaimers are either misunderstood or simply ignored, causing patients to unwittingly put themselves at risk. Furthermore, all the products do not contain these disclaimers and should be made to in order to clearly identify the risk to patients using these products.

The FDA is responsible for ensuring the safety and efficacy of drugs, medical devices, biological products, cosmetics, food, and radiation-emitting products in the USA, but the FDA has little authority over dietary supplements and is specifically prevented from closely regulating the industry.25 Product labels and claims are not subject to the same approval requirements as drug labels and dietary supplements are not subject to the same rigorous testing standards. Consequently, dietary supplement manufacturers have a substantial amount of latitude in what they can say and do. For example, dietary supplement labels may not be as clear as they should be, such as with the ambiguity in ingredient listings noted in Table 2. Because of the FDA’s limited authority over dietary supplements, they are not as well regulated as drugs in terms of safety, consistency, efficacy, or labeling, and may be at higher risk of misinformation or even hazardous contents, including gluten. Although the addition of gluten to these products is a clear contraindication for patients with CD, patients with nonceliac gluten sensitivity might also be sensitive to the amounts of gluten in these products and should be aware of these issues.

Tolerase G, the AN-PEP-based supplement, was not evaluated in this study because it was not found via the search methods used. This is likely a result of the time at which the searches were conducted, the search terms used, and the Google search algorithm. Tolerase G became commercially available in June, approximately 1 month prior to when the searches were conducted, which may have contributed to the apparent low visibility through the Google searches. While Tolerase G effectively reduced the amount of consumed gluten that was exposed to the duodenum in a clinical study, it did not completely degrade the gluten.9 Therefore, it is not an effective treatment for CD, as no safe concentration of gluten in the duodenum has been determined, and the same study even states, ‘AN-PEP is not intended to treat or prevent coeliac disease’.9 Tolerase G, being a dietary supplement, is also not FDA regulated and therefore has the same regulation concerns as the supplements evaluated in this study.

With the potential hazards and lack of evidence of efficacy of the glutenase products we investigated, it appears entirely inadvisable for patients with CD to use the products. Rather, it remains that the only valid treatment option presently available for CD is lifelong adherence to the GFD. There are, however, some promising therapies currently being developed in the United States and Europe that will be required to demonstrate efficacy and safety in clinical trials. It is most advisable that patients with CD maintain GFD while awaiting the approval and production of safe, properly regulated therapies. We need to ask all our patients on GFDs with CD or nonceliac gluten sensitivity about their use of dietary supplements and protect them from this very poorly regulated industry and specifically the misleading labeling of these glutenase products, especially as patients increasingly use the internet to seek medical information.26

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Suneeta Krishnareddy, Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, Columbia University, New York, USA.

Kenneth Stier, Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, Columbia University, New York, USA.

Maya Recanati, Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, Columbia University, New York, USA.

Benjamin Lebwohl, Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, Columbia University, New York, USA.

Peter HR Green, Celiac Disease Center, Columbia University Medical Center, 180 Fort Washington Avenue, Room 936, New York, NY 10032, USA.

References

- 1. Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 1731–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shan L, Molberg O, Parrot I, et al. Structural basis for gluten intolerance in celiac sprue. Science 2002; 297: 2275–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Janssen G, Christis C, Kooy-Winkelaar Y, et al. Ineffective degradation of immunogenic gluten epitopes by currently available digestive enzyme supplements. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0128065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shan L, Marti T, Sollid LM, et al. Comparative biochemical analysis of three bacterial prolyl endopeptidases: implications for coeliac sprue. Biochem J 2004; 383: 311–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ehren J, Moron B, Martin E, et al. A food-grade enzyme preparation with modest gluten detoxification properties. PLoS One 2009; 4: e6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gass J, Bethune MT, Siegel M, et al. Combination enzyme therapy for gastric digestion of dietary gluten in patients with celiac sprue. Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 472–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tye-Din JA, Anderson RP, Ffrench RA, et al. The effects of ALV003 pre-digestion of gluten on immune response and symptoms in celiac disease in vivo. Clin Immunol 2010; 134: 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mitea C, Havenaar R, Drijfhout JW, et al. Efficient degradation of gluten by a prolyl endoprotease in a gastrointestinal model: implications for coeliac disease. Gut 2008; 57: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salden BN, Monserrat V, Troost FJ, et al. Randomised clinical study: Aspergillus niger-derived enzyme digests gluten in the stomach of healthy volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 273–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee A, Newman JM. Celiac diet: its impact on quality of life. J Am Diet Assoc 2003; 103: 1533–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee AR, Ng DL, Diamond B, et al. Living with coeliac disease: survey results from the U.S.A. J Hum Nutr Diet 2012; 25: 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hall NJ, Rubin GP, Charnock A. Intentional and inadvertent non-adherence in adult coeliac disease: a cross-sectional survey. Appetite 2013; 68: 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tennyson CA, Simpson S, Lebwohl B, et al. Interest in medical therapy for celiac disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2013; 6: 358–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aziz I, Evans KE, Papageorgiou V, et al. Are patients with coeliac disease seeking alternative therapies to a gluten-free diet? J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2011; 20: 27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sollid LM, Khosla C. Novel therapies for coeliac disease. J Intern Med 2011; 269: 604–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wolf C, Siegel JB, Tinberg C, et al. Engineering of Kuma030: a gliadin peptidase that rapidly degrades immunogenic gliadin peptides in gastric conditions. J Am Chem Soc 2015; 137: 13106–13113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lahdeaho ML, Kaukinen K, Laurila K, et al. Glutenase ALV003 attenuates gluten-induced mucosal injury in patients with celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2014; 146: 1649–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Byun T, Kofod L, Blinkovsky A. Synergistic action of an X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase and a non-specific aminopeptidase in protein hydrolysis. J Agric Food Chem 2001; 49: 2061–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koch S, Anthonsen D, Skovbjerg H, et al. On the role of dipeptidyl peptidase IV in the digestion of an immunodominant epitope in celiac disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 2003; 524: 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Board NTE. Herbal supplements without the herbs. New York Times, 6 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Newmaster SG, Grguric M, Shanmughanandhan D, et al. DNA barcoding detects contamination and substitution in North American herbal products. BMC Med 2013; 11: 222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 22. Nazareth S, Lebwohl B, Voyksner JS, et al. Widespread contamination of probiotics with gluten, detected by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: S28. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vallabhaneni S, Walker TA, Lockhart SR, et al. Notes from the field: fatal gastrointestinal mucormycosis in a premature infant associated with a contaminated dietary supplement – Connecticut, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64: 155–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kesselheim AS, Connolly J, Rogers J, et al. Mandatory disclaimers on dietary supplements do not reliably communicate the intended issues. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015; 34: 438–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. FDA. Dietary Supplement Health and Educational Act of 1994. 1994, https://health.gov/dietsupp/ch1.htm (accessed 6 June 2016).

- 26. McMullan M. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient–health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns 2006; 63: 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]