Abstract

Effective programs for youth can reduce problem behaviors and promote positive development. In particular, cultural assets (e.g., ethnic-racial identity) are important for African American youth’s health and development. In this article, we argue that youth programs represent an important social context for African American youth’s development of positive ethnic-racial identity and we present a conceptual framework for understanding how such programs may affect African American youth’s development in this area. Then we provide examples of evidence-based programs that have assessed this developmental process among African American youth. We conclude with considerations for research.

Keywords: adolescents, youth programs, racial identity, ethnic identity

Since the turn of the 20th century, organizations that serve youth have been an important social context for positive development (1, 2). Consequently, researchers and policymakers have become increasingly interested in what constitutes quality and effectiveness in programming for youth. Given the variability in programs for youth (e.g., mission, approach, target population), we lack definitive answers. However, Eccles and Gootman’s (3) seminal review described several guiding characteristics (e.g., programs that provide a physically and psychologically safe atmosphere, programs that have a developmentally appropriate structure). Many effective programs adopt some form of philosophy about youth development, promoting the 5Cs (competence, confidence, connection, character, and caring; 4) or emphasizing developmental assets involving internal (e.g., personal identity) and external (e.g., family, youth programs) assets (5). Generally, when programs for youth work, we expect them to deter problem behavior and promote positive development.

Although the importance of racial and ethnic diversity is implied within several youth development perspectives, research on race and ethnicity with regard to youth programs is limited (6). Programs designed to change youth’s developmental trajectories should be tailored to the social experiences of participants (7). For African American youth, a growing body of literature underscores the importance of cultural assets for positive development (8). In this article, we focus on one cultural asset: ethnic-racial identity.

The Importance of Ethnic-Racial Identity for African American Youth

Identity formation is widely recognized as a normative developmental process through which a young person understands his or her place in the social world. Youth who have achieved a positive sense of identity are more likely to behave prosocially and less likely to engage in risky behaviors (9). However, normative developmental transitions for African American youth are embedded within several complex social systems (10). Negative race-based experiences (e.g., discrimination and bias) can impair their search for identity (11), while positive race-based experiences can promote a positive search for identity (12). Ethnic-racial identity protects against the negative effects of racial and ethnic discrimination, and is associated with health and positive development in African American youth (11, 13). Therefore, establishing a positive ethnic-racial identity is an important part of African American youth’s development.

We conceptualize ethnic-racial identity as a multidimensional psychological construct that represents the aspect of a person’s overall identity that is associated with race or ethnicity (14). It involves the aspects of one’s identity derived from ethnic-racial identifications, the complex process through which an individual explores and consolidates membership in ethnic-racial groups, feelings associated with membership in those groups, and society’s views about one’s ethnic or racial group (15). In addition, African Americans can be thought of in terms of both race and ethnicity (15). Therefore, we use the term ethnic-racial identity to capture this psychological construct with consideration for African American youth’s experiences in forming this aspect of their identity.

Early to middle adolescence is a critical phase for forming ethnic-racial identity (15, 16). While infants can detect racial (e.g., skin color, facial features) and ethnic (e.g., language) differences (17), and children can identify ethnic-racial groups but do not necessarily think about how group membership affects their lives (15), adolescence is when individuals draw meaning from their ethnic-racial experiences (16). The probability of experiencing discrimination also increases in adolescence as African American youth spend more time outside the home in social settings such as schools and neighborhoods (13), and they contemplate how those experiences may affect their lives (18). For some youth, experiencing discrimination can initiate a search for and exploration of ethnic-racial identity (19). We propose that youth programs represent an important setting for African American teenagers to process these experiences and develop positive ethnic-racial identities.

Conceptual Framework

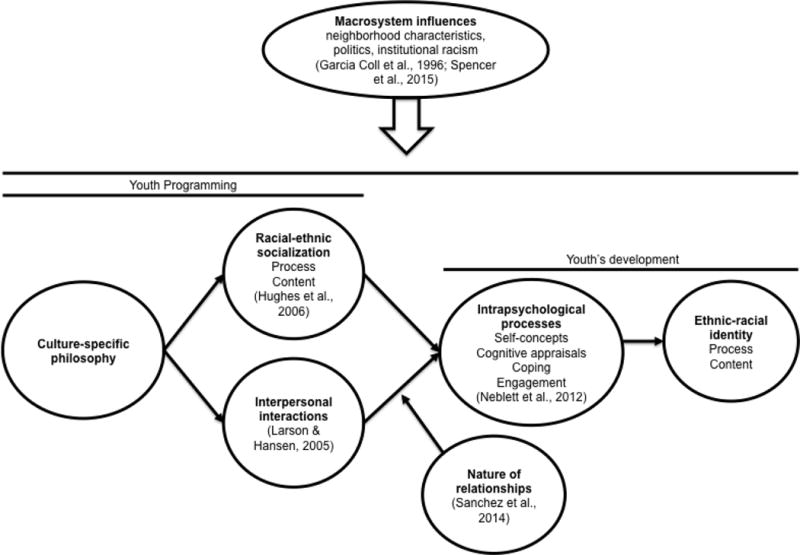

Our framework is informed by several developmental theories (10, 21). We propose that youth programs promote African American youth’s development of ethnic-racial identity by adopting a culture-specific philosophy that informs racial-ethnic socialization practices (e.g., choice of culture-specific curriculum and activities) and opportunities for meaningful interpersonal interactions (see Figure 1). Elements of programs for youth are influenced by the nature of interpersonal relationships within the program and mediated by youth’s intrapsychological processes. This process is embedded within several macrosystem influences that affect both the program and African American youth.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model depicting the association between youth programs and African American youlh’s ethnic-racial identity

Scholars have argued that broader social contexts (e.g., institutional racism, racial denigration, and marginalization) obstruct and conflict with racially marginalized youth’s search for a positive identity (10, 21). Indeed, macrosystem influences affect both African American youth and youth programs. For example, the staff of programs for youth may feel pressure to frame urban African American youth’s identity negatively to obtain funding (22). However, culturally informed theories on risk and resilience emphasize the role of cultural assets for African American youth’s healthy development (23). Youth programs might highlight philosophies (e.g., African American and Africentric worldviews) that position African American culture as an asset. Adopting such philosophies would inform programming that supports African American youth’s development of positive identity.

Racial-ethnic socialization is the process through which parents communicate with their children about race and ethnicity (20). This form of socialization is also a multidimensional concept that involves process and content (8). Process includes direct strategies (e.g., having conversations with youth) and indirect strategies (e.g., displaying cultural artifacts) through which ideas about race and ethnicity are transmitted. Content involves messages regarding maintaining heritage and understanding the history of one’s cultural origin (cultural socialization), strategies for coping with discrimination (preparation for bias), messages about egalitarianism (e.g., equality), guidance on succeeding in mainstream society (mainstream socialization), and less frequently, cautions about being wary of other racial groups (promotion of mistrust; 8, 20, 24). Racial-ethnic socialization is associated positively with African American youth’s ethnic-racial identity (12).

Racial-ethnic socialization is important for African American youth in programs (25). By offering culturally relevant curriculum and activities, youth programs are uniquely positioned to offer a place for African American youth to talk with adults and peers about social issues that affect their lives (e.g., African American history, racial profiling in their neighborhoods, the Black Lives Matter movement) in a youth-centered environment. Such activities likely initiate and support the development of ethnic-racial identity. We propose that racial-ethnic socialization within youth programs might mirror research on parenting in process and content. Programs are likely to transmit messages to African American youth about race and ethnicity (e.g., cultural heritage, interracial interactions, preparation for bias). In this scenario, we expect to see direct forms of socialization (e.g., conversations about ethnicity, field trips to cultural institutions) as well as indirect forms (e.g., displaying of cultural artifacts). However, youth programs differ from families in that they compete for funding (and raise funds) to support their work, select facilitators to communicate the messages, and vary in terms of program cycles (e.g., weeks to months), and because participants and staff members change, all of which may change the social dynamic of youth’s interactions in programs. When participants change—something that can occur frequently because of lack of interest, interest in attending other programs, staff turnover, and for other reasons—social dynamics between staff and youth and among youth are affected. Therefore, unique forms of socialization may emerge through further investigation.

Interpersonal interactions with adults and peers are integral components of learning in youth programs. In some programs, youth practice developing identities with the support of program staff through activities such as social advocacy (26). Furthermore, staff’s attitudes about race and ethnicity can affect the social, cultural, and emotional environment of youth programs for African American youth (22). In fact, staff members who are biased and reinforce stereotypes can do more harm than good to African American youth’s development of identity (27). Thus, we further propose that the impact of interpersonal interactions in youth programs is moderated by the nature of the relationships with individuals in the program. Ethnically and racially similar adults can play a positive role in African American youth’s formation of ethnic-racial identity (28).

Finally, the ability for youth programs to affect African American youth’s ethnic-racial identity is influenced by youth’s intrapsychological processes (8, 16). African American youth may accept (or reject) race-related messages communicated through a program for many reasons, including their own interests, the perceived importance or utility of the messages, individual coping abilities, or psychological engagement in the program.

Evidence of African American Youth’s Ethnic-Racial Identity in Youth Programs

To assess whether and how programs for youth affect African American youth’s ethnic-racial identity, we applied our framework to the research, searching the literature using several engines (e.g., Google Scholar, PsycINFO) that extracted articles featuring relevant terms (e.g., racial identity, ethnic identity, youth development, and youth program). We limited our review to programs that included African American participants, using terms such as Black, and African American.1 We identified 13 youth programs that reported development of racial or ethnic identity as a central focus of the program’s philosophy or approach, and involved African American children or adolescents (see Table 1). In this article, we provide examples of how programs influenced African American youth’s development of ethnic-racial identity. (For detailed descriptions of the programs, please refer to the articles cited in Table 1.)

Table 1.

Review of youth programs that discussed racial-ethnic identity among African American youth

| Program | Goal | Design | Age range | Setting | ERI Measure | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aban Aya | To promote individual and community protective factors in order to reduce youth risk behaviors | intervention versus control | 5th–8th grade | school | n/a | 29 |

| Fathers and Sons | To improve parenting practices and abilities among nonresident fathers in order to reduce youth risk behaviors | intervention versus control | ages 8–12 | community | n/a | 30 |

| Flourish Agenda | To promote community change by developing leadership skills in youth; promote youth’s social action | cohort | high school | community | Longitudinal qualitative interviews and analysis | 38 |

| Health intervention (gender/culture specific) | To promote youth’s resilience by increasing self-esteem, sense of culture and challenge masculine/feminine beliefs | intervention versus control | ages 10–12 | after school | Children’s Racial Identity Scale | 31 |

| Imani Rites of Passage | To provide educational and cultural enrichment | cohort | ages 11–14 | after school | Retrospective qualitive interview | 39 |

| MAAT Rites of Passage Program | To promote cooperation, sameness of self and others, and responsibility for connection between self and community | pretest versus posttest | ages 11–14 | after school | author-developed measure | 32 |

| NTU: Substance Abuse Prevention | To promote youth’s protective factors in order to reduce risk behaviors | intervention versus control | 5th–6th grade | school | Children’s Racial Identity Scale | 40 |

| Project EXCEL | To promote youth’s psychological and behavioral well-being | intervention versus control | 8th grade | school | Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure | 33 |

| Sisters of Nia | To promote psychological and psychosocial wellbeing, reinforce positive interpersonal relationships and provide health education | intervention versus control | middle school | after school | Children’s Racial Identity Scale | 41 |

| Strong African American Families | To deter youth risk behaviors by supporting effective parenting practices and abilities | intervention versus control | 11 years old | community | Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity | 42 |

| Understanding Violence | To raise awareness about causes and consequences of youth violence, and increase intent to use nonviolent choices | school-wide prevention program | 5th grade | school | n/a | 43 |

| Young Empowered Sisters | To promote healthy Black identity and collectivist orientation, increase awareness of racism, and encourage participation in liberatory activism | intervention versus control | high school | school | Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure | 44 |

| Youth Empowerment Solutions for Peaceful Communities | To promote youth and community qualities in order to reduce youth violence and improve youth health outcomes | stratified community-wide prevention | 7th–8th grade | community | n/a | 45 |

The 13 programs focused on myriad outcomes, including intellectual and personal development, social and emotional learning, physical and sexual health, and preventing violence. All programs were designed around youth’s developmental readiness (e.g., participants were in middle school or high school). Eleven programs involved youth in grades 5–8 (ages 10–14); two programs involved youth in high school. In 12 programs, all participants were African Americans, and one program included African American and Latino students. The curricula and activities considered youth’s ages and expected that their cognitive abilities would allow them to understand complex topics (e.g., structural racism, sense of self), and emphasized development of identity as a critical task in early to late adolescence. All programs had specific goals and were implemented with intentional program structure.

To our knowledge, 4 of the 13 programs (Aban Aya, Fathers and Sons, Understanding Violence, and Youth Empowerment Solutions for Peaceful Communities) have not been evaluated for their direct or indirect impact on African American youth’s ethnic-racial identity, so we did not include them. We focused our analysis on the nine programs that assessed African American youth’s racial or ethnic identity.2 (For additional information on these programs, see Table 2.) Although it is unclear what impact these programs had on African American youth’s ethnic-racial identity, they used culturally responsive approaches to prevention, intervention, or youth development (e.g., they featured cultural awareness and designed curriculum to meet the needs of the intended community) and succeeded across several domains of development, including reducing risky behaviors (29) and improving parent-child relationships (30).

Table 2.

Review of youth programs that assessed African American youth’s ethnic-racial identity

| Program | Philosophy | ERI components | Change in ERI | Other outcomes | Examples of curriculum and activities | Gender effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flourish Agenda | Social justice youth development | exploration/search, understanding of common fate, affect | Increased | Increased political consciousness |

|

n/d |

| Health intervention (gender/culture specific) | Africentric worldview | composite of affect, cognition, and behaviors | Stable | Increased Africentric cultural values, and self-concept |

|

females |

| Imani Rites of Passage | Africentric worldview | exploration/search, identification | Increased | Increased academic performance, awareness of black-on-black violence, collectivism and coping abilities |

|

males |

| MAAT Rites of Passage Program | Nguzo Saba | n/d | Stable | Increased self-esteem and knowledge of drugs |

|

males |

| NTU: Substance Abuse Prevention | Nguzo Saba | composite of affect, cognition, and behaviors | Increased | Increased knowledge of Africa and self-esteem; reduced negative school behaviors and promoted positive school behaviors |

|

n/d |

| Project EXCEL | East African Ujamaa | affect, exploration/search, behaviors | Decreased | Increased communalism, school connectedness, motivation, and participation in social change activities |

|

n/d |

| Sisters of Nia | Nguzo Saba | composite of affect, appearance, and rejection of stereotypes | Increased | Decreased relational aggression+ |

|

females |

| Strong African American Families | culturally informed prevention | affect | Increased | Improved parenting abilities; increased adolescent’s self-pride, peer orienation, and reduced sexual intent; decreased adolescent risky sexual behaviors |

|

n/d |

| Young Empowered Sisters | Nguzo Saba; Freiren conscientization and praxis, and holistic learning | composite of affect, exploration/search, behaviors | Increased | Increased racism awareness, collectivist orientation, and liberatory youth activism |

|

females |

Notes: ERI = Ethnic or racial identity; n/d = not discussed;

= Authors reported a trend toward significance, controlling for baseline, F(1, 44) = 3.48, p = .07

Six programs reported positive effects on ethnic-racial identity. During the transition to middle school, racial identity was stable among girls in the intervention group but declined among girls in the control group (31). One program had no effect on African American boys’ racial identity (32) but no comparison group was included; the boys may have been stable compared to a control group, similar to findings involving girls. Only one program had negative effects on the development of ethnic identity (33): African American youth in the intervention group declined in three domains of ethnic identity (i.e., affirmation and belonging, achievement, and ethnic behaviors), while African American youth in the control group increased in ethnic identity.

Macrosystem Influences

Not surprisingly, all the programs highlighted institutional or structural racism as the impetus for the program (e.g., lack of culturally responsive educational, prevention, or intervention programming for African American youth). Although implied in several programs, a few programs (Imani Rites of Passage, Project EXCEL, Strong African American Families) highlighted the importance of university-community partnerships to share knowledge and bolster resources. Most of the programs were implemented in urban settings. However, only Imani Rites of Passage described the community context, the center through which programming was offered, and the impact of funding streams on programming. And only one program (Strong African American Families) was for rural youth and families. In this case, the researchers contextualized the needs of the participants within a geographical context (i.e., the rural South).

Culture-Specific Philosophy

All nine programs adopted some form of culture-specific philosophy, often reflecting Africentric perspectives that placed African or African American heritage and culture centrally. Several programs used the seven principles of Nguzo Saba and its guidelines and practices for healthy living, which are designed to strengthen African American families, communities, and culture (34). The principles are umoja (unity), kujichagulia (self-determination), ujima (collective work and responsibility), ujamaa (cooperative economics), nia (purpose), kuumba (creativity), and imani (faith). The programs that used Nguzo Saba were MAAT Rites of Passage, NTU: Substance Abuse Prevention, Sisters of Nia, and Young Empowered Sisters.

Other culture-specific philosophies embedded in the programs included Africentric worldviews that promote African cultural values involving spirituality, harmony, and collective responsibility (e.g., Imani Rites of Passage). Project EXCEL was based on the East African Ujamaa philosophy, which emphasizes sharing, cooperation, and respect. Flourish Agenda’s approach was informed by Social Justice Youth Development perspectives, which emphasizes analyzing power within social relationships, promoting systematic change, encouraging collective action, and making identity central (35). The Strong African American Families program adopted a culturally informed approach to prevention informed by the research team’s work with African American families and developed with consideration for the experiences of rural African American youth and their parents.

Racial-Ethnic Socialization

Consistent with research on parenting (20), racial-ethnic socialization in youth programs involved process and content. Promotional messages focused on facilitating and preserving African and African American heritage and culture (cultural socialization), promoting racial-ethnic pride (e.g., natural hair care), and building positive collective identity (e.g., “I am because we are [Ubuntu]” and “One life, one love, one people”). Some programs communicated messages about social inequities, developing a sense of collective struggle, and ways to cope with racism (e.g., preparation for bias).

The ways messages were communicated varied across programs (see Table 2: Examples of curriculum and activities), with direct socialization strategies the most common. These practices included featuring culture-specific curriculum (e.g., books and other materials), completing research projects, attending lectures and workshops on culture-relevant topics, participating in cultural practices (e.g., unity circles, naming ceremonies, African drumming), engaging in educational activities (e.g., field trips to an African American museum), and hearing African languages (e.g., Swahili). We found little discussion of indirect forms of racial-ethnic socialization (e.g., displaying art work), but all programs were intentional in hiring African American staff and facilitators, which may be an indirect form of socialization.

Interpersonal Interactions

Most programs used interactive activities, including group projects (e.g., fundraising, community service), role playing, and interactive games to facilitate interpersonal interactions. These activities generally provided opportunities for youth and program facilitators (e.g., staff, guest speakers) to interact and learn together. Many programs also used dialogue. For example, African American youth in Flourish Agenda discussed collective struggle and developed strategies to address social inequity. Strong African American Families used an innovative family-centered prevention model to facilitate conversations between African American youth and their parents about community violence, racism, and oppression. Some programs promoted kinship among staff, youth in the program, and youth and the broader community. For example, male youth in the MAAT Rites of Passage program referred to adult men as baba (father), adult women as mama, and young peers as brother. Sisters of Nia used the word Jamaa to represent family.

Nature of Relationships

A few programs underscored the importance of the nature of relationships. When feasible, facilitators of the same race and gender as youth facilitated the programming (e.g., Sisters of NIA, Young Empowered Sisters). Sisters of Nia’s African American female staff, called mzees (Kiswahili for respected elder), were presented as role models for female youth. Similarly, African American women facilitated Young Empowered Sisters, a program for African American high school girls.

Intrapsychological Processes

A few programs addressed the role of youth’s intrapsychological processes. The negative effects of Project EXCEL on ethnic identity may be due to the fact that the curriculum focused heavily on encounters with racism and preparation for bias, which may have caused some African American youth to distance themselves psychologically from their ethnic group to protect their sense of self (33). Some programs (e.g., Flourish Agenda, Project EXCEL, Young Empowered Sisters) used critical pedagogy—a teaching approach to help students address social inequities through reflection, dialogue, and the development of strategies to reduce inequality—to raise African American youth’s racial awareness and social consciousness, and promote the development of ethnic-racial identity.

Considerations for Research

Collectively, these studies support the notion that youth programs can promote African American youth’s ethnic-racial identity. Although research has not addressed interactions with peers, they are also an important feature of learning in youth programs. Therefore, research is needed to understand how peer-to-peer interactions affect African American youth’s development of ethnic-racial identity in youth programs.

Furthermore, it is less clear how these findings vary as a function of youth’s intrapsychological processes (e.g., cognitive appraisals, engagement). Researchers should investigate whether the effectiveness of programming varies as a function of African American youth’s ethnic-racial identity. They should also identify which practices affect specific domains of ethnic-racial identity (e.g., activities that facilitate pride versus psychological distancing).

Most of the programs chose facilitators intentionally based on the premise that staff should understand African American youth’s backgrounds and cultural values, have extensive experience working in African American communities, or present themselves as positive role models for African American youth. Other studies support the importance of matching by ethnicity and gender in programs for African American youth, especially in programs that promote reproductive and sexual health (36). These studies seem to support the importance of such matching in youth programs that promote African American youth’s ethnic-racial identity; however, researchers should investigate these assumptions further.

Finally, although our focus was on African American youth, our conceptual framework should be relevant for other culturally underrepresented groups in the United States (e.g., Latino/Hispanic, Asian American, Native American) and youth in other ethnically heterogeneous countries. In fact, scholars have suggested that ethnic-racial identity is an important aspect of youth’s development in societies where youth must position themselves as members of a minority group within the mainstream culture (37). Therefore, we urge researchers to examine the relevance of this conceptual framework in work with diverse groups of youth.

Conclusion

Ethnic-racial identity plays an important role in African American youth’s positive development. Programs for youth can positively influence African American youth’s development of ethnic-racial identity, which has implications not only for African American youth’s positive development in these programs but also for policy and practice regarding youth programming in African American communities. Thus, policymakers and funding agencies should support the work of effective youth programs that promote African American youth’s cultural assets, such as ethnic-racial identity. Gaining a deeper understanding of how youth programs work will help make programs more engaging and effective for African American youth.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Theresa Thorkildsen for providing insight on this article and Ashley Williams for participating in discussions regarding youth programs. This publication was made possible by Grant Nos. K12HD055892 and R03HD077128 from the Eunice K. Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Research on Women’s Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD or the NIH. Dr. Brittian’s work on this article was supported in part by a Scholar Grant from the Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Footnotes

The Understanding Violence program did not provide disaggregated data on ethnic heritage; all participants were described as Black. African American participants in the Imani Rites of Passage program were reported as majority Caribbean descent.

In this section, we used terms the authors reported in their work (e.g., some authors reported ethnic identity, while others reported racial identity).

Contributor Information

Aerika Brittian Loyd, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Brittney V. Williams, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Illinois at Chicago

References

- 1.Catalano RF, Berglund ML, Ryan JA, Lonczak HS, Hawkins JD. Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;591:98–124. doi: 10.1177/0002716203260102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahoney JL, Vandell DL, Simpkins S, Zarrett N. Adolescent out-of school activities. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3rd. Vol. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. pp. 228–267. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eccles J, Gootman JA, editors. Community programs to promote youth development. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerner RM. Liberty: Thriving and civic engagement among American youth. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scales P, Benson P, Leffert N, Blyth DA. The contribution of developmental assets to the prediction of thriving among adolescents. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4:27–46. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads0401_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams JL, Deutsch NL. Beyond between-group differences: Considering race, ethnicity, and culture in research on positive youth development programs. Applied Developmental Science. 2015 doi: 10.1080/10888691.2015.1113880. Advance online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernal G, Jiménez-Chafey MI, Domenech Rodríguez MM. Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:361–368. doi: 10.1037/a0016401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neblett EW, Jr, Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor AJ. The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meeus W, Iedema J, Helsen M, Vollenberg W. Patterns of adolescent identity development: Review of the literature and longitudinal analysis. Developmental Review. 1999;19:419–461. doi: 10.1006/drev.1999.0483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, Vasquez-Garcia H. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. doi: 10.2307/1131600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Umaña-Taylor AJ. A post-racial society in which ethnic-racial discrimination still exists and has significant consequences for youths’ adjustment. Current Directions for Psychological Science. 2016;25:111–118. doi: 10.1177/0963721415627858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neblett EW, Smalls CP, Nguyen HX, Ford KR, Sellers RM. Racial socialization and racial identity: African American parents’ messages about race as precursors to identity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:189–203. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, Lewis RH. Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:187–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00128.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom CA, Quintana SM, Syed M, Lee RM, Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group Ethnic and racial identity in childhood and adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development. 2014;85:40–57. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE, Jr, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group Ethnic and racial identity revisited: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development. 2014;85:21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spencer MB, Swanson DP, Harpalani V. Development of the self. In: Lamb ME, editor. Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 7th. New York, NY: Wiley; 2015. pp. 750–793. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly DJ, Quinn PC, Slater AM, Lee K, Ge L, Pascalis O. The other race effect develops during infancy. Psychological Science. 2007;18:1084–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris-Britt A, Valrie CR, Kurtz-Costes B, Rowley SJ. Perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem in African American youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:669–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Syed M, Azmitia M. A narrative approach to ethnic identity in emerging adulthood: Bringing life to the identity status model. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1012–1027. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ racial-ethnic socialization practices: A review of research and agenda for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer MB. Phenomenology and ecological systems theory: Development of diverse groups. In: Damon W, Lerner R, editors. Child and Adolescent Development: An Advanced Course. New York, NY: Wiley; 2008. pp. 696–740. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldridge BJ. Relocating the deficit: Reimagining Black youth in neoliberal times. American Educational Research Journal. 2014;51:440–472. doi: 10.3102/0002831214532514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmerman MA, Stoddard SA, Eisman AB, Caldwell CH, Aiyer SM, Miller A. Adolescent resilience: Promotive factors that inform prevention. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7:215–220. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lesane-Brown CL. A review of race socialization within Black families. Developmental Review. 2006;26:400–426. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2006.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones SCT, Neblett EW. Racial-ethnic protective factors and mechanisms in psychosocial prevention and intervention programs for Black youth. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2016;19:134–161. doi: 10.1007/s10567-016-0201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larson R, Hansen D. The development of strategic thinking: Learning to impact human systems in a youth activism program. Human Development. 2005;48:327–349. doi: 10.1159/000088251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson R, Walker KC. Dilemmas of practice: Challenges to program quality encountered by youth program leaders. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;45:338–349. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9307-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez B, Colon-Torres Y, Feuer R, Roundfield KE, Berardi L. Race, ethnicity, and culture in mentoring relationships. In: DuBois DL, Karcher MJ, editors. Handbook of youth mentoring. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014. pp. 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flay BR, Graumlich S, Segawa E, Burns JL, Holliday MY. Effects of 2 prevention programs on high-risk behaviors among African American youth. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:377–384. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caldwell C, Rafferty J, Reischl T, De Loney E, Brooks C. Enhancing parenting skills among nonresident African American fathers as a strategy for preventing youth risky behaviors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;45:17–35. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9290-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belgrave FZ, Chase-Vaughn G, Gray F, Addison JD, Cherry VR. The effectiveness of a culture- and gender-specific intervention for increasing resiliency among African American preadolescent females. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:133–147. doi: 10.1177/0095798400026002001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvey AR, Hill RB. Africentric youth and family rites of passage program: Promoting resilience among at-risk African American youths. Social Work. 2004;49:65–74. doi: 10.1093/sw/49.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis KM, Andrews E, Gaska K, Sullivan C, Bybee D, Ellick KL. Experimentally evaluating the impact of a school-based African-centered emancipatory intervention on the ethnic identity of African American adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology. 2012;38:259–289. doi: 10.1177/0095798411416458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karenga M. The Nguzo Saba (the seven principles): Their meaning and message. In: Asante MK, Abarry AS, editors. African intellectual heritage: A book of sources. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1996. pp. 543–554. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ginwright S, Cammarota J. New terrain in youth development: The promise of a social justice approach. Social Justice. 2002;29:82–95. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bandy T, Moore KA. What works for African American children and adolescents: Lessons from experimental evaluations of programs and interventions. Washington, DC: Child Trends; 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2016, from http://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/2011-04WhatWorkAAChildren.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Meca A, Ritchie RA. Identity around the world: An overview. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2012;138:1–18. doi: 10.1002/cad.20019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ginwright SA. Black youth activism and the role of critical social capital in Black community organizations. American Behavioral Scientist. 2007;51:403–418. doi: 10.1177/0002764207306068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whaley AL, McQueen JP. An Afrocentric program as primary prevention for African American youth: Qualitative and quantitative exploratory data. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2004;25:253–269. doi: 10.1023/B:JOPP.0000042389.22212.3a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cherry VR, Belgrave FZ, Jones W, Kennon DK, Gray FS, Phillips F. NTU: An Africentric approach to substance abuse prevention among African American youth. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1998;18:319–339. doi: 10.1023/A:1024607028289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belgrave FZ, Reed MC, Plybon LE, Butler DS, Allison KW, Davis T. An evaluation of Sisters of Nia: A cultural program for African American girls. Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30:329–343. doi: 10.1177/0095798404266063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murry VM, Berkel C, Brody GH, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX. The Strong African American Families program: Longitudinal pathways to sexual risk reduction. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nikitopoulos CE, Waters JS, Collins E, Watts CL. Understanding Violence: A school initiative for violence prevention. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2009;37:275–288. doi: 10.1080/10852350903196282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas O, Davidson W, McAdoo H. An evaluation study of the Young Empowered Sisters (YES!) Program: Promoting cultural assets among African American adolescent girls through a culturally relevant school-based intervention. Journal of Black Psychology. 2008;34:281–308. doi: 10.1177/0095798408314136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zimmerman MA, Stewart SE, Morrel-Samuels S, Franzen S, Reischl TM. Youth empowerment solutions for peaceful communities: Combining theory and practice in a community-level violence prevention curriculum. Health Promotion Practice. 2011;12:425–439. doi: 10.1177/1524839909357316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]